The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Responsibility

2.2. Relationships between Organizational Ethics and Social Responsibility

2.3. Employees’ WB

2.4. Relationships between Employees’ WB, SR, and OE

3. Methodology

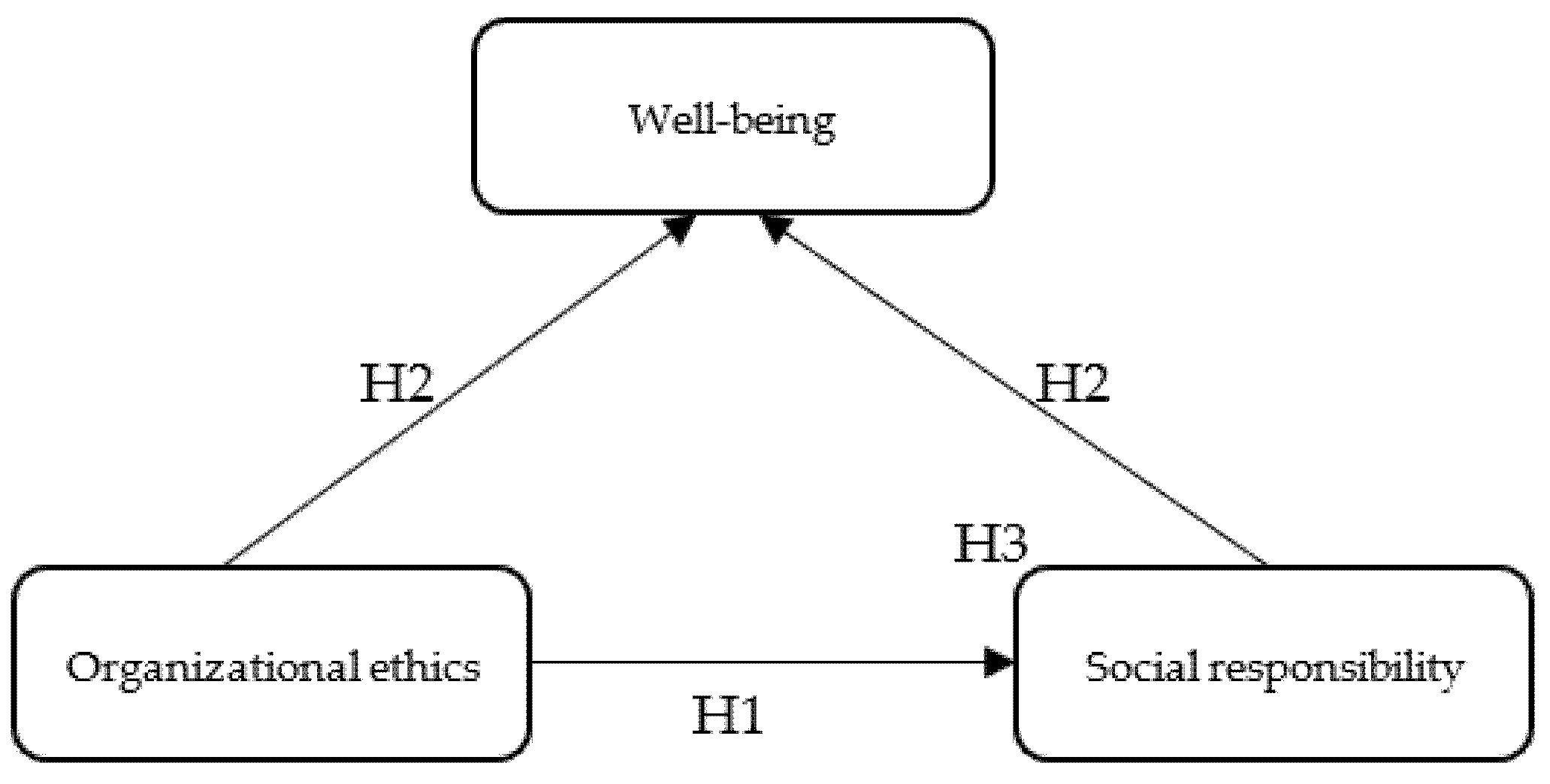

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Selected Sample

3.3. Research Tools and Methods

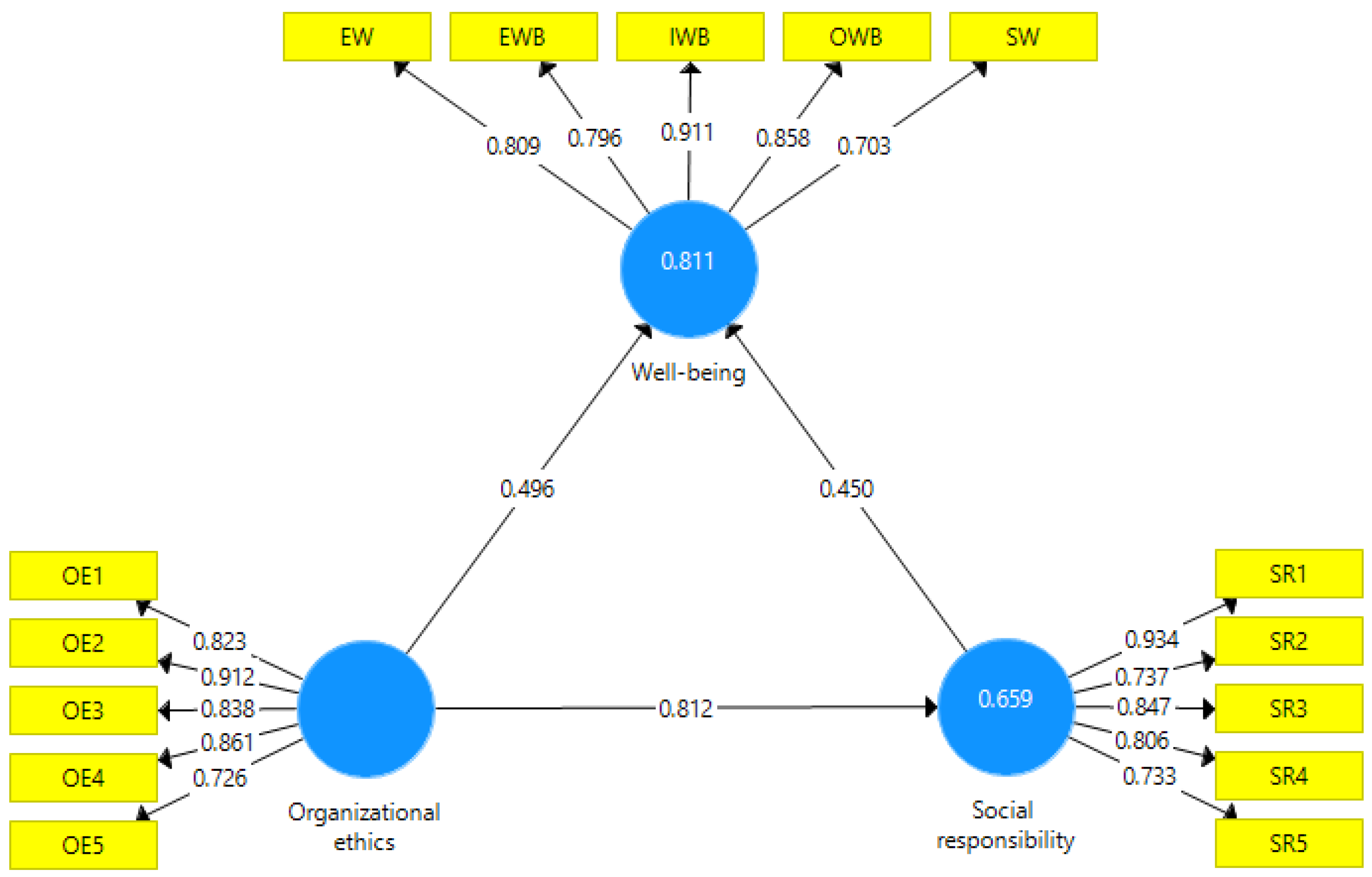

4. Results

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zizek, S.S.; Mulej, M.; Potocnik, A. The Sustainable Socially Responsible Society: Well-Being Society 6.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; López-Martínez, G.; Molina-Moreno, V. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability. A Bibliometric Analysis of Their Interrelations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.Y.; Gray, E.R. Socially responsible entrepreneurs: What do they do to create and build their companies? Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciortino, R. Philanthropy in Southeast Asia: Between charitable values, corporate interests, and development aspirations. ASEAS-Austrian J. South-East Asian Stud. 2017, 10, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rela, I.Z.; Awang, A.H.; Ramli, Z.; Ali, M.N.S.; Manaf, A.A. Corporate social responsibility practice and its effects on community well-being in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Chapter 24, pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Macassa, G.; Francisco, J.C.; McGrath, C. Corporate social responsibility and population health. Health Sci. J. 2017, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.J.; Shin, Y.; Choi, N.J.; Kim, S.M. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.N. Human resource training and development as facilitators of CSR. J. Econ. Dev. 2012, 14, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Iftekhar, H.; Aslam, M.S.; Razzaq, A. A conceptual framework on examining the influence of behavioral training & development on CSR: An employees’ perspective approach. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wambui, T.W.; Wangombe, J.G.; Muthura, M.W.; Kamau, A.W.; Jackson, S.M. Managing workplace diversity: A Kenyan perspective. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbilgin, M.F.; Beauregard, T.A.; Tatli, A.; Bell, M.P. Work-life, diversity, and intersectionality: A critical review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 13, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciortino, R. Philanthropy, giving, and development in Southeast Asia. ASEAS-Austrian J. South-East Asian Stud. 2017, 10, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Blomstrom, R. Business and Society: Environment and Responsibility; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, D.P.; Reindenbach, R.E. Social Responsibility, Ethics, and Marketing Strategy: Closing the gap between concept and application. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M. Exploring the poverty reduction potential of social marketing in tourism development. Austrian J. South-East Asian Stud. 2015, 8, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. The Sustainable Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Sinha, P.; Chen, X. Corporate social responsibility and eco-innovation: The triple bottom line perspective. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. COVID-19 and the Future of CSR Research. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 58, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.T.; Fukukawa, K.; Gray, E.R. The Nature and Management of Ethical Corporate Identity: A Commentary on Corporate Identity, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, R.B. Pink Slips Profits, and Paychecks: Corporate Citizenship in an Era of Smaller Government; School of Business and Public Management, George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, W.; Fuller, S. Increasing Corporate Social Responsibility Through an Employee-centered Approach. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2009, 21, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, A.E. Practices at the Boundaries of Business Ethics Corporate Social Responsibility. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Painter-Morland, M. Triple bottom line reporting as social grammar. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M. Reputation, relationships, and risk: A CSR primer for ethics officers. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2006, 111, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, E. Is it time for a unified approach to business ethics? SCCE Compliance Ethics Mag. 2008, 5, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanie, S.; Karadas, G.; Lawrence Emeagwali, O. Do CSR Perceptions InfluenceWork Outcomes in the Health Care Sector? The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and Employee Attachment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, C.G.; Luloff, A.E.; Finley, J.C. Where is “community” in community-based forestry? Soc. Nat. Res. 2008, 21, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.L. Locating social capital in resilient community-level emergency management. Nat. Hazards 2007, 41, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakopoulou, S.; Dawson, J.; Gari, A. The community well-being questionnaire: Theoretical context and initial assessment of its reliability and validity. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 56, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.L. Community Well-Being: An Overview of the Concept; Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R.W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Employee subjective well-being and physiological functioning: An integrative model. Health Psychol. Open 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthill, M. Coolangatta: A portrait of community well-being. Urban Policy Res. 2002, 20, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, D.; Smit, B. Rural community well-being: Models and application to changes in the tobacco-belt in Ontario, Canada. Geoforum 2002, 33, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, R.; Walton, A.; Leonard, R. A conceptual framework for investigating community well-being and resilience. Rural Soc. 2014, 23, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, A.; Edwards, L. Community well-being indicators, survey template for local government. In Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government; University of Technology: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, R.J.; Brown, D.M. Recreation, tourism, and rural well-being. In Tourism and Hospitality; Economic Research Report No. 1477-2016-121194; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A. Employee traps—corruption in the workplace. Manag. Rev. 1997, 86, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge, R.B.; Skandali, N.; Dayan, P.; Dolan, R.J. Dopaminergic modulation of decision making and subjective well-being. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 9811–9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpino, R.A.; Avramchuk, A.S. The Conceptual Relationship between Workplace Well-Being, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Healthcare Costs. Int. Manag. Rev. 2017, 13, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, J.; Steiner, G. Business, Government, and Society: A Managerial Perspective, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tov, W. Well-being concepts and components. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Millstein, R.A.; von Hippel, C.; Howe, C.J.; Powers Tomasso, L.; Wagner, G.R.; Vander Weele, T.J. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Widgery, R.N.; Lee, D.J.; Grace, B.Y. Developing a measure of community well-being based on perceptions of impact in various life domains. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 96, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, J.; Brasher, K. Community well-being in an unwell world: Trends, challenges, and possibilities. J. Public Health Policy 2008, 29, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forjaz, M.J.; Prieto-Flores, M.E.; Ayala, A.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Martinez-Martin, P. Measurement properties of the community well-being index in older adults. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kee, Y.; Lee, S.J. An analysis of the relative importance of components in measuring community well-being: Perspectives of citizens, public officials, and experts. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Des Moines, IA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). Corporate Social Responsibility: Meeting Changing Expectations; WBCSD: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Lu, W. The inverse U-shaped relationship between corporate social responsibility and competitiveness: Evidence from Chinese international construction companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.P.; Pauze, E.; Guo, K.; Kent, A.; Jean-Louis, R. The physical activity and nutrition-related corporate social responsibility initiatives of food and beverage companies in Canada and implications for public health. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, H. How does CSR activity affect sustainable growth and value of corporations? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwobu, O.A. Corporate Social Responsibility, and the Public Health Imperative: Accounting and Reporting on Public Health. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Orlando, B., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/74802 (accessed on 8 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, E.H.; Backlund Rambaree, B.; Macassa, G. CSR reporting of stakeholders’ health: Proposal for a new perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F. The Impact of CSR Perceptions on Employees’ Turnover Intention during the COVID-19 Crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor-Zambrano, H.Y.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Relationship CSR and employee commitment: Mediating effects of internal motivation and trust. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj, T.B. Effects of corporate social responsibility towards stakeholders and environmental management on responsible innovation and competitiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Gabriel, P.K. Understanding employee responses to COVID-19: A behavioral corporate social responsibility perspective. Manag. Res. 2020, 18, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvăo, A.; Mendes, L.; Marques, C.; Mascarenhas, C. Factors Influencing Students’ Corporate Social Responsibility Orientation in Higher Education. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Zehou, S.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, H.Q.; Ali, I.; Sajjad, A.; Ilyas, M. Impact of internal corporate social responsibility on employee engagement: A study of a moderated mediation model. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. 2016, 30, 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- Zanko, M.; Dawson, P. Occupational health and safety management in organizations. A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macassa, G.; McGrath, C.; Tomaselli, G.; Buttigieg, S.C. Corporate social responsibility and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being in Europe: A systematic descriptive review. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 866–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K.; Dartey-Baah, K. Occupational health and safety: Key issues and concerns in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagawati, B. Basics of occupational safety and health. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxic Food Technol. 2015, 9, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vărzaru, M.; Vărzaru, A.A. Leadership style and organizational structure in Mintzberg’s vision. In Proceedings of the 7th International Management Conference: New Management for the New Economy, Bucharest, Romania, 26 August–7–8 November 2013; pp. 467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Vărzaru, M.; Vărzaru, A.A. Knowledge Management and Organisational Structure: Mutual Influences. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Unit Politecnica, Cartagena, Cartagena, Spain, 6–7 September 2012; pp. 1255–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Vărzaru, A.A.; Vărzaru, D. Organizational performance and its control through budgets. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Business Excellence, Brasov, Romania, 14–15 October 2011; Volume 2, pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Vărzaru, A.A. Problems in the design and implementation of a costing system. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts (SGEM 2015), Albena, Bulgaria, 26 August–1 September 2015; Volume 3, pp. 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action for Employees, Workers, Policy Makers, and Practitioners; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J. Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melovic, B.; Milovic, N.; Backovic-Vulic, T.; Dudic, B.; Bajzik, P. Attitudes, and Perceptions of Employees toward Corporate Social Responsibility in Western Balkan Countries: Importance and Relevance for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Ong, T.S.; Meero, A.; Rahman, A.A.A.; Ali, M. Employee-perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) and employee pro-environmental behavior (PEB): The moderating role of CSR skepticism and CSR authenticity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakunskiene, E. Assessment of the Impact of Social Responsibility on Poverty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A. Assessing the Impact of AI Solutions’ Ethical Issues on Performance in Managerial Accounting. Electronics 2022, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A. Design and implementation of a management control system. Financ. Chall. Future 2015, 17, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- De los Salmones, M.G.; Crespo, A.H.; del Bosque, I.R. Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaland, A.J.; Lwin, M.O.; Murphy, P.E. Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigne, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TINYpulse The Only Workplace Wellness Survey Template You Need to Get Real Insights. Available online: https://www.tinypulse.com/blog/employee-survey-questions-about-wellness-and-health (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A personcentric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Boadi, E.; He, Z.; Bosompem, J.; Opata, C.N.; Boadi, E.K. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its effects on internal outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, M.A.; Carnelley, K.B.; Sedikides, C. Attachments in the workplace: How attachment security in the workplace benefits the organisation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 50, 1046–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Ruiz, L.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J. How corporate social responsibility activities influence employer reputation: The role of social media capability. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 129, 113223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The Int. J. Human Res. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Ruiz-Amaya, C.; Knorr, H. Employee organizational citizenship behavior: Ethical leadership’s direct and indirect impact. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2011, 28, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J.; Roztocki, N. Do organizational ethics improve IT job satisfaction in the Visegrad Group countries? Insights from Poland. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 18, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudencio, P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The role of trust in corporate social responsibility and worker relationships. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourvakas, G.; Yfantidou, I. Corporate social responsibility influences employee engagement. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, B.; van Eijbergen, R.; Rietzschel, E.F.; Scheibe, S. Catering to the needs of an aging workforce: The role of employee age in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and employee satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Abdullah, M.I.; Alvi, A.T. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility impact on employee outcomes: Mediating role of organizational justice for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martinez, J.B.; Fernaíndez, M.L.; Fernaíndez, P.M.R. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degie, B.; Kebede, W. Corporate social responsibility and its prospect for community development in Ethiopia. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, Y.; Junwu, C.; Addae-Boateng, S. Corporate social responsibility activities of mining companies: The views of the local communities in Ghana. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmila, S.M.; Zaimah, R.; Lyndon, N.; Hussain, M.Y.; Awang, A.H. Local community economic well-being through CSR project. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmotkin, D. Subjective well-being as a function of age and gender: A multivariate look for differentiated trends. Soc. Indic. Res. 1990, 23, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 32, 103–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E.; Diener, E.; Fujita, F. Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munz, D.C.; Kohler, J.M.; Greenberg, C.I. Effectiveness of a Comprehensive Worksite Stress Management Program: Combining Organizational and Individual Interventions. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.; Taylor, P.; Johnson, S.; Cooper, C.; Cartwright, S.; Robertson, S. Work environments, stress, and productivity: An examination using ASSET. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 22, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Miyazaki, A.D.; Taylor, K.A. The Influence of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Choice: Does One Good Turn Deserve Another? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Elsbach, K.D. Us versus Them: The Roles of Organizational Identification and Disidentification in Social Marketing Initiatives. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 22, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantani, D.; Peltzer, R.; Cremonte, M.; Robaina, K.; Babor, T.; Pinsky, I. The marketing potential of corporate social responsibility activities: The case of the alcohol industry in Latin America and the Caribbean. Addiction 2017, 222, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.; Wu, J.Y.W.; Wang, C.S.; Pan, L.H. Health-promoting Lifestyles and Psychological Distress Associated with Well-being in Community Adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 42, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gül, Ö.; Qaglayan, H.S.; Akandere, M. The Effect of Sports on the Psychological Well-being Levels of High School Students. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Employees’ Weekend Activities and Psychological Well-Being via Job Stress: A Moderated Mediation Role of Recovery Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 27, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Min | Max | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic sector | 1 | 4 | 2.81 | 0.981 | −0.239 | −1.048 |

| Size | 1 | 3 | 1.80 | 0.748 | 0.345 | −1.146 |

| Gender | 1 | 2 | 1.30 | 0.459 | 0.875 | −1.241 |

| Age | 1 | 5 | 2.70 | 1.099 | 0.606 | −0.250 |

| Education | 1 | 5 | 3.30 | 1.101 | −0.615 | −0.237 |

| Experience in work | 1 | 5 | 2.30 | 1.345 | 0.669 | −0.762 |

| Experience in organization | 1 | 5 | 2.91 | 1.136 | 0.187 | −0.752 |

| Position | 1 | 2 | 1.20 | 0.399 | 1.517 | 0.301 |

| Income category | 1 | 5 | 2.91 | 1.512 | −0.012 | −1.443 |

| Latent Variables | Exogenous Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Code | Description | |

| WB | GWB | General WB |

| EWB | Emotional WB | |

| EW | Environmental wellness | |

| IWB | Intellectual WB | |

| OWB | Occupational WB | |

| PH | Physical health | |

| SWB | Social WB | |

| SW | Spiritual wellness | |

| OE | OE1 | Transparency |

| OE2 | Fair competition | |

| OE3 | Respect for the customer | |

| OE4 | The organization treats employees well | |

| OE5 | Sustainability | |

| SR | RS1 | Organizational citizenship |

| RS2 | Societal contribution | |

| RS3 | Societal welfare | |

| RS4 | Organizational SR philosophy | |

| RS5 | Increasing the organizational value | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational ethics | 0.889 | 0.919 | 0.696 |

| Social responsibility | 0.875 | 0.907 | 0.664 |

| Wellbeing | 0.879 | 0.910 | 0.670 |

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational ethics → Social responsibility (H1) | 0.812 | 0.011 | 71.746 | 0.000 |

| Organizational ethics → Wellbeing (H2) | 0.496 | 0.033 | 15.031 | 0.000 |

| Social responsibility → Wellbeing (H2) | 0.450 | 0.033 | 13.462 | 0.000 |

| Organizational ethics → Social responsibility → Wellbeing (H3) | 0.365 | 0.023 | 15.637 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bocean, C.G.; Nicolescu, M.M.; Cazacu, M.; Dumitriu, S. The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148838

Bocean CG, Nicolescu MM, Cazacu M, Dumitriu S. The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148838

Chicago/Turabian StyleBocean, Claudiu George, Michael Marian Nicolescu, Marian Cazacu, and Simona Dumitriu. 2022. "The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148838

APA StyleBocean, C. G., Nicolescu, M. M., Cazacu, M., & Dumitriu, S. (2022). The Role of Social Responsibility and Ethics in Employees’ Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148838