A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Housing Tenants’ Concerns about Property Habitability and the Implementation of Habitability Laws in Southern Nevada

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clark County Landlord–Tenant Hotline

2.2. Nevada Housing Statutes

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Quantitative Data

2.3.2. Qualitative Data

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Quantitative

2.4.2. Qualitative

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

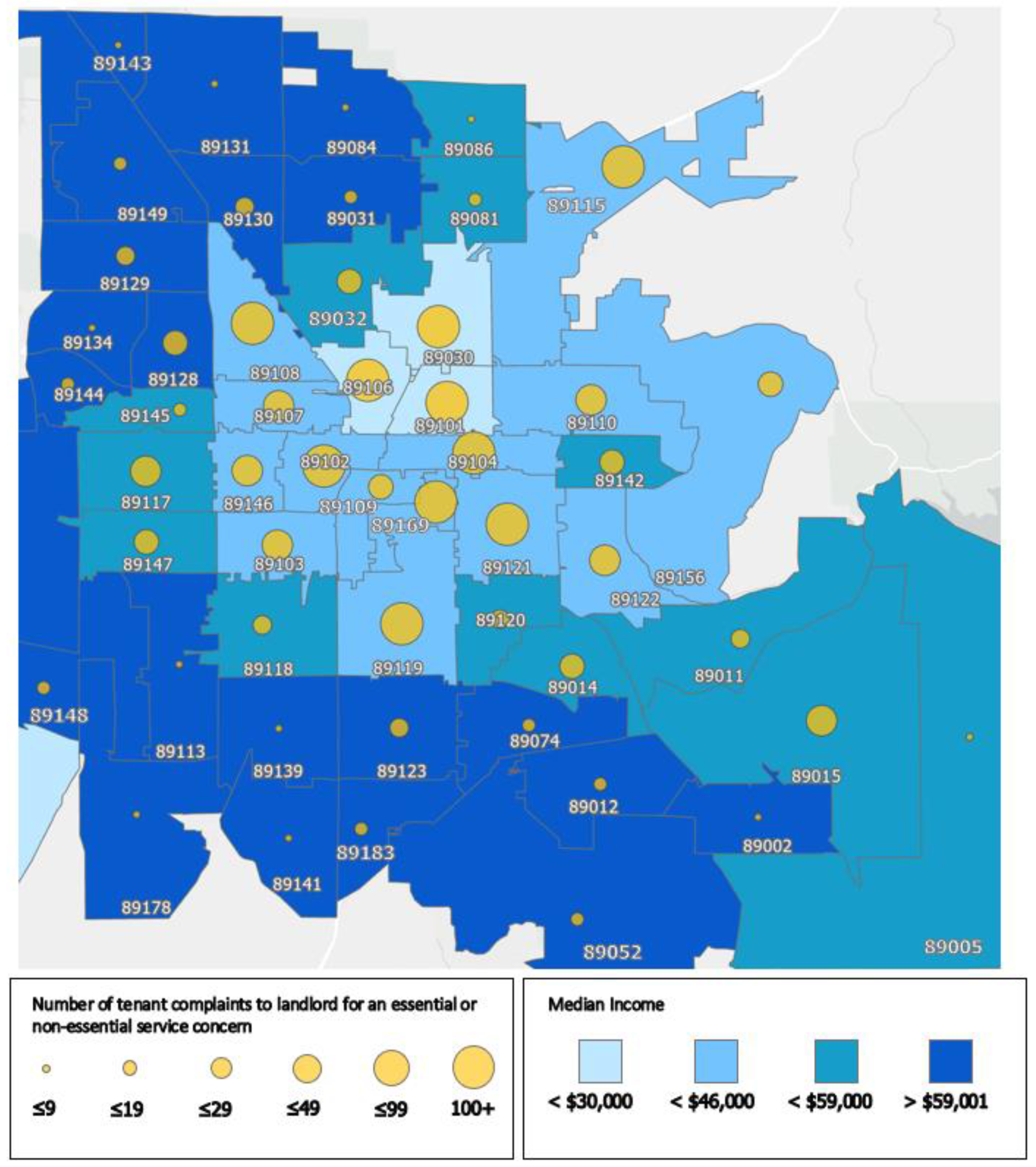

3.1.1. Summary and Assessment of Tenant Habitability Concerns by Income

3.1.2. Addressing Housing Concern Resolutions by Income

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Theme: Resources to Navigate Landlord–Tenant Laws Are Limited

“Like the only thing I kept doing was going in there … complaining to her, like what’s going on with this apartment? … So definitely, when I called the hotline … they went [through the process] what I’m going to do, how to go about doing it.”(Interviewee, 003)

“Um, somewhat but they really couldn’t do anything for the situation. Uhm, they just like told me kind of how to go about it.”(Interviewee, 012)

“They tried but their hands are tied. They can’t. The program can’t do anything but come and look and put down on paper. They can’t stop these people. They can’t assist you with anything else. So you know as far as being helpful. Yes they came out and looked [but] they couldn’t help.”(Interviewee, 002)

“The only problem is the when it pertains to my situation with mold there is no strict regulation on how they repair it … the issue is there is no regulation saying the landlord has to get this certified mold removed by a mold tester. Before he can say hey it’s done its clean and put the wall back together. He didn’t even want to tear the wall apart.”(Interviewee, 004)

“… when I got my 5-day notice, I went down there and they helped me do the paperwork myself so that I could go to court … they helped out a whole lot as far as me having to serve [my landlord] with papers so that he could fix stuff …”(Interviewee, 013)

“I went and asked for help but … they were not helpful either. They said it was like a 50/50 chance and … since the landlord he went and did a heat treatment … if he did all that then we were probably going to lose the case and then we were going to end up paying the landlord for like the lawyer and stuff … We went through losing all our stuff…”(Interviewee, 005)

3.2.2. Theme: Housing Policies Need to Be Strengthened to Help Tenants and Keep People Housed

“Well like when it’s a situation where the apartment is possibly uninhabitable due to either health risk or even if it’s something to do with the landlord neglecting, uhm, you know repairs … We need to have some sort of third party, you know? The health district, or whomever, would be part of that to say, ‘hey you know this dwelling is not inhabitable for your tenant. You know if you don’t fix this within a sort of amount of time we are going to allow your tenant to either hire someone or they’re going to get out of the lease.’”(Interviewee, 004)

“They should find a place or they should find another unit that’s similar to ours and the same rent that they pay for or just give it to us for free until we can move back into our unit and pay that next month’s rent.”(Interviewee, 006)

“… I think that would be better like if they were able to be fined or something was to happen to where it would cost them more money to pay what or to do whatever than to pay to fix the unit. I think that would make it so much better.”(Interviewee, 006)

“… the landlords have to like specifically state all policies … As well as giving the tenants more options for emergency cases or difficult cases. Like, it’s one thing if I just said oh I don’t like this apartment I want to move. It’s another for me to tell you that I don’t feel safe the fact that you have to send a letter to tell me it’s not safe … and you not be able to accommodate that in a better manner.”(Interviewee, 014)

“Guidelines [that] you are supposed disclose any prior leaks. Major leaks. Any issues with the unit. And they don’t do that. And if they don’t and you find out. They should face a fine. Because that is the law. They are supposed to … disclose anything that was prior wrong with the unit.”(Interviewee, 002)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Qualitative Questions.

- Landlord–Tenant Hotline.

- How has the Landlord–Tenant Hotline been helpful in addressing your complaint?

- How do you think the Landlord–Tenant Hotline can be changed to address your needs?

- Often the Landlord–Tenant Hotline refers callers to legal services. Did you contact legal services?

- Did you find it helpful?

- Can you discuss the process?

- Proposed Rental Housing Policy.

- What do you think about a policy focused on keeping your home healthy?

- If implemented what would be the benefits for you as a renter?

- If implemented what would be the cons for you as a renter?

- What should be a part of this policy that is important to you as a renter?

References

- Swope, C.B.; Hernández, D. Housing as a Determinant of Health Equity: A Conceptual Model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 243, 112571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Palacios, J.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N.; Aydin, E. The Impact of Housing Conditions on Health Outcomes. Real Estate Econ. 2020, 49, 1172–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.; Higgins, D.L. Housing and Health: Time Again for Public Health Action. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskabady, M.; Marefati, N.; Farkhondeh, T.; Shakeri, F.; Farshbaf, A.; Boskabady, M.H. The Effect of Environmental Lead Exposure on Human Health and the Contribution of Inflammatory Mechanisms, a Review. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Housing and Health. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/Housing-and-health/housing-and-health (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Bryant-Stephens, T.C.; Strane, D.; Robinson, E.K.; Bhambhani, S.; Kenyon, C.C. Housing and Asthma Disparities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pindus, M.; Janson, C.; Sigsgaard, T.; Kim, J.L.; Holm, M.; Sommar, J.; Orru, H.; Gislason, T.; Johannessen, A.; et al. Dampness, Mould, Onset and Remission of Adult Respiratory Symptoms, Asthma and Rhinitis. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, C.; Guiney, C. Living in a Cold and Damp Home: Frameworks for Understanding Impacts on Mental Well-Being. Public Health 2015, 129, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, E.; Blank, L.; Crowder, M.; Ferrari, E.; Goyder, E. Exploring the Relationship between Housing Concerns, Mental Health and Wellbeing: A Qualitative Study of Social Housing Tenants. J. Public Health 2020, 42, E231–E238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, A.; Daniel, L.; Baker, E.; Bentley, R. Housing Disadvantage and Poor Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Housing Survey (AHS)—Table Creator. American Housing Survey. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/interactive/ahstablecreator.html?s_areas=00000&s_year=2017&s_tablename=TABLE10&s_bygroup1=2&s_bygroup2=10&s_filtergroup1=1&s_filtergroup2=1 (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Grineski, S.E.; Hernández, A.A. Landlords, Fear, and Children’s Respiratory Health: An Untold Story of Environmental Injustice in the Central City. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2010, 15, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, E.; Dodge Francis, C.; Gerstenberger, S. Where I Live: A Qualitative Analysis of Renters Living in Poor Housing. Health Place 2019, 58, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Comparative Housing Characteristics. American Community Survey. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?t=Housing%3AHousing%20Units&g=0500000US32003&tid=ACSCP5Y2020.CP04 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Housing Survey (AHS)—Table Creator. American Housing Survey. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/interactive/ahstablecreator.html?s_areas=29820&s_year=2017&s_tablename=TABLE5&s_bygroup1=7&s_bygroup2=2&s_filtergroup1=1&s_filtergroup2=1 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Won, J.; Lee, J.S. Impact of Residential Environments on Social Capital and Health Outcomes among Public Rental Housing Residents in Seoul, South Korea. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowsky, A.N. Health Hazards in Rental Housing: An Overview of Clark County; University of Nevada: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, S.; Woodman, J. Using Mixed Methods in Health Research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRS Chapter 118A. Nevada Revised Statutes Chapter 118A—Landlord and Tenant: Dwellings; Nevada Law Library. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/nevada/2021/chapter-118a/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- NRS § 118A.290. Chapter 118A—Landlord and Tenant Dwellings. Nevada Law Library. Available online: https://www.leg.state.nv.us/nrs/nrs-118a.html (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, P.; Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Analysing and Presenting Qualitative Data. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuckartz, U. Mixed Methods. Methodology, Research Designs and Methods of Data Analysis; Springer: Marburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. FY 2015 Income Limits Documentation System—Median Income Calculation for Clark County, Nevada. HUD User. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il/il2015/2015MedCalc.odn?inputname=Clark%20County&area_id=METRO29820M29820&fips=3200399999&type=county&year=2015&yy=15&stname=Nevada&statefp=32&areaname=Clark%20County&ACS_Survey=$ACS_Survey$&State_Count=$State_Count$&stusps=NV (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Desmond, M.; Wilmers, N.; Blossom, J.; Boeing, G.; Bucholtz, S.; Carpenter, A.; Cole, T.; Davis, J.; de Laurell, D.; Goldman, M.; et al. Do the Poor Pay More for Housing? Exploitation, Profit, and Risk in Rental Markets 1. AJS 2019, 124, 1090–1124. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime; Office of Policy Development and Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/summer16/highlight2.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Kane, J.W.; Tomer, A. Parks Make Great Places, But Not Enough Americans Can Reach Them; Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/08/21/parks-make-great-places-but-not-enough-americans-can-reach-them/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- National Recreation and Parks Association. Parks & Recreation in Underserved Areas: A Public Health Perspective; National Recreation and Parks Association: Ashburn, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelli, H.M.; Kim, J.H.; Tahhan, A.S.; Liu, C.; Ko, Y.A.; Hammadah, M.; Sullivan, S.; Sandesara, P.; Alkhoder, A.A.; Choudhary, F.K.; et al. Living in Food Deserts and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2019, 8, e010694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reardon, S.F.; Fox, L.; Townsend, J. Neighborhood Income Composition by Household Race and Income, 1990–2009. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 660, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurand, A.; Emmanel, D.; Crowley, S. THE GAP: The Affordable Housing Gap Analysis 2016; The National Low Income Housing Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Data USA. Clark County, NV. Data USA. Available online: https://datausa.io/profile/geo/clark-county-nv/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- White, S.; McGrath, M.M. Rental Housing and Health Equity in Portland, Oregon: A Health Impact Assessment of the City’s Rental Housing Inspections Program; OPHI: Portland, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, N.; Phillips, M.; Ryan, K.; Bursac, Z.; Ferguson, A. Examining the Strength of State Habitability Laws across the United States of America. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2017, 17, 541–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legal Services Corporation. The Unmet Need for Legal Aid. LSC. Available online: https://www.lsc.gov/about-lsc/what-legal-aid/unmet-need-legal-aid (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Income Limits | N | % |

| Very Low Income (50% of Median Household Income 1 ≤ USD 30,700) | 459 | 16 |

| Low Income (80% of Median Household Income ≤ USD 30,700–49,100) | 2133 | 74.4 |

| Above Median Household Income (≥USD 59,200) | 273 | 9.5 |

| Essential Tenant Habitability Concerns | N | % |

| Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) Outage | 392 | 13.7 |

| Water Outage | 185 | 6.5 |

| Electric or Gas Outage | 28 | 1 |

| Nonessential Tenant Habitability Concerns | N | % |

| Mold | 975 | 34 |

| General Maintenance | 931 | 32.5 |

| Bed Bugs | 540 | 18.8 |

| Cockroaches | 427 | 14.9 |

| Other (e.g., problems with sinks, toilets, neighbors) | 235 | 8.2 |

| Other Insects | 170 | 5.9 |

| Odor | 164 | 5.7 |

| Sewage | 131 | 4.6 |

| Rodents | 85 | 3 |

| Pigeons | 39 | 1.4 |

| Domestic Animals | 33 | 1.2 |

| Deficiency Corrected | Deficiency Not Corrected | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At or below 80% of median income | 62 (35.2%) | 114 (64.8%) | 176 |

| Above 80% of median income | 30 (66.7%) | 60 (33.3%) | 90 |

| Total | 92 (34.6%) | 174 (65.4%) | 266 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marquez, E.; Coughenour, C.; Gakh, M.; Tu, T.; Usufzy, P.; Gerstenberger, S. A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Housing Tenants’ Concerns about Property Habitability and the Implementation of Habitability Laws in Southern Nevada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148537

Marquez E, Coughenour C, Gakh M, Tu T, Usufzy P, Gerstenberger S. A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Housing Tenants’ Concerns about Property Habitability and the Implementation of Habitability Laws in Southern Nevada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148537

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarquez, Erika, Courtney Coughenour, Maxim Gakh, Tiana Tu, Pashtana Usufzy, and Shawn Gerstenberger. 2022. "A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Housing Tenants’ Concerns about Property Habitability and the Implementation of Habitability Laws in Southern Nevada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148537

APA StyleMarquez, E., Coughenour, C., Gakh, M., Tu, T., Usufzy, P., & Gerstenberger, S. (2022). A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Housing Tenants’ Concerns about Property Habitability and the Implementation of Habitability Laws in Southern Nevada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148537