The Implication of Physically Demanding and Hazardous Work on Retirement Timing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Higher PDWT increases the likelihood of retirement (within two years).

- Exposure to PHWE increases the likelihood of retirement (within two years).

- The influence of PDWT on retirement vs. continued work increases with age.

- The influence of PHWE on retirement vs. continued work increases with age.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variable

2.2.2. Stratification Variables

2.2.3. Exposure Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Age Moderating Effects

2.3.2. Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

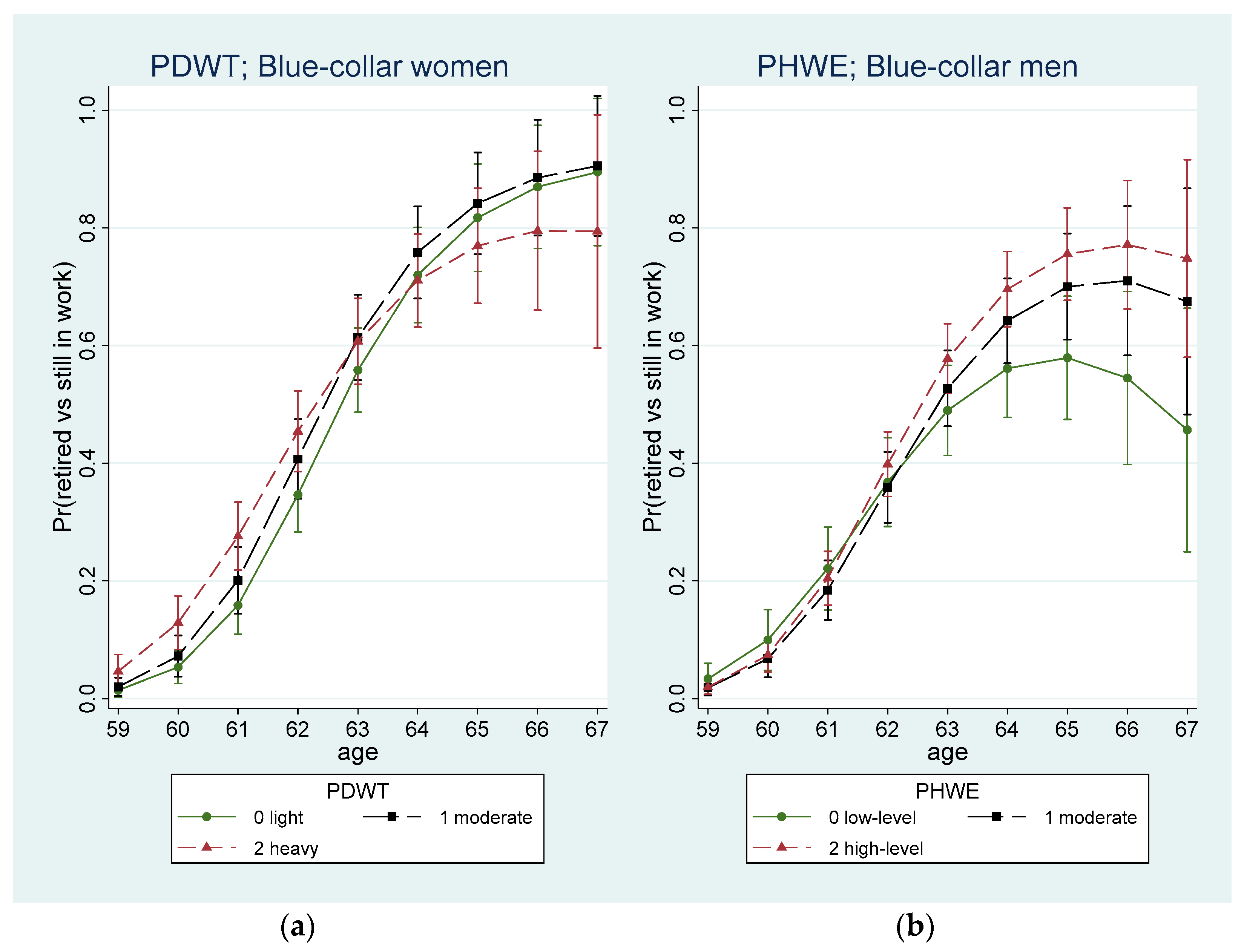

3.1. The Moderating Effect of Age for Blue-Collar Wokers (Model 4)

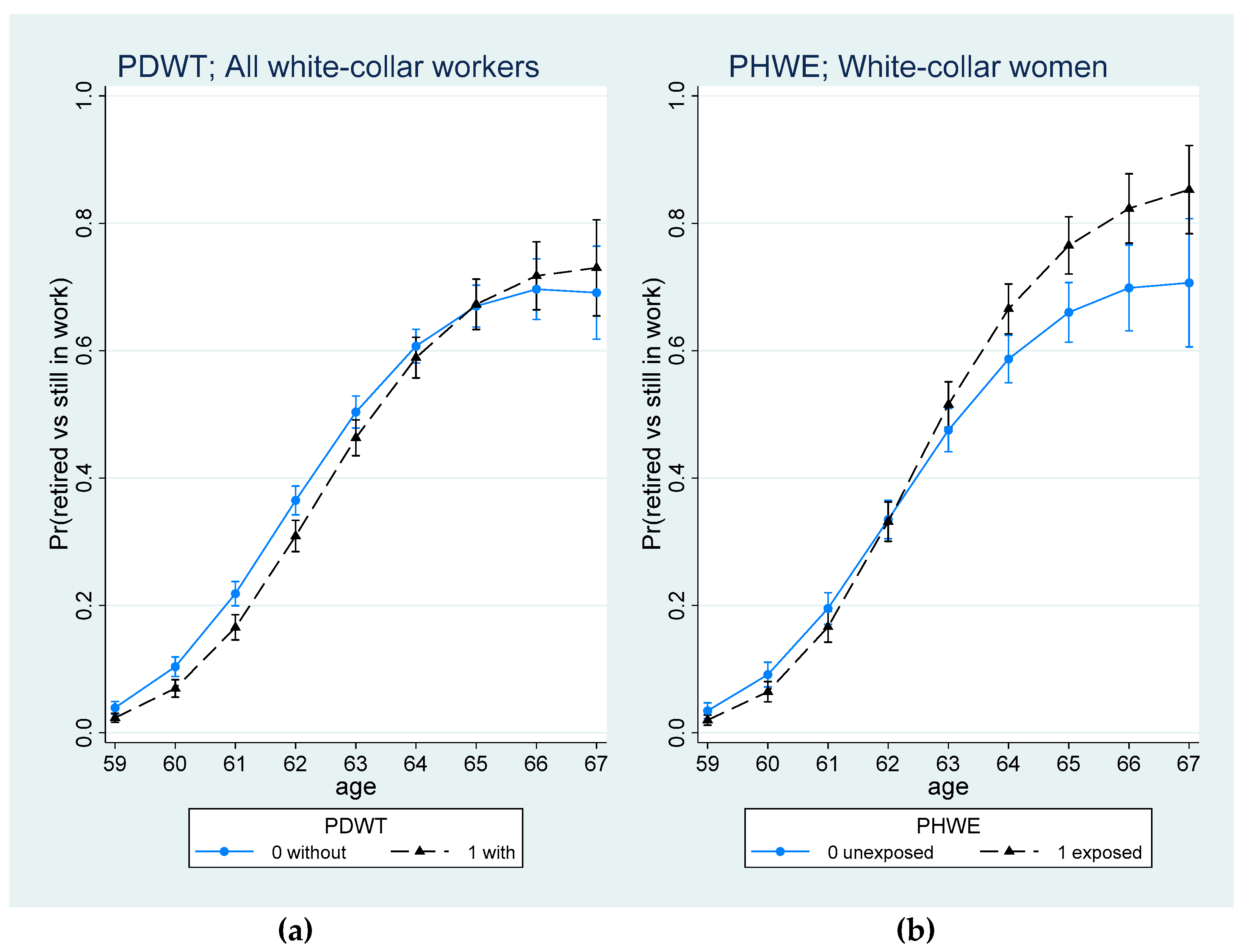

3.2. The Moderating Effect of Age for White-Collar Wokers (Model 4)

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Physically Demanding Work Tasks

4.2. Physically Hazardous Work Environment

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Björklund Carlstedt, A.; Brushammar, G.; Bjursell, C.; Nystedt, P.; Nilsson, G. A scoping review of the incentives for a prolonged work life after pensionable age and the importance of “bridge employment”. Work 2018, 60, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noone, J.; Knox, A.; O’Loughlin, K.; McNamara, M.; Bohle, P.; Mackey, M. An Analysis of Factors Associated With Older Workers’ Employment Participation and Preferences in Australia. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe—Looking at the Lives of Older People in the EU, 2019th ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, K.; Hydbom, A.R.; Rylander, L. Factors influencing the decision to extend working life or retire. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2011, 37, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.L.; Villadsen, E.; Clausen, T. Influence of physical and psychosocial working conditions for the risk of disability pension among healthy female eldercare workers: Prospective cohort. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 48, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundstrup, E.; Hansen, Å.M.; Mortensen, E.L.; Poulsen, O.M.; Clausen, T.; Rugulies, R.; Møller, A.; Andersen, L.L. Cumulative occupational mechanical exposures during working life and risk of sickness absence and disability pension: Prospective cohort study. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2017, 43, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lahelma, E.; Laaksonen, M.; Lallukka, T.; Martikainen, P.; Pietiläinen, O.; Saastamoinen, P.; Gould, R.; Rahkonen, O. Working conditions as risk factors for disability retirement: A longitudinal register linkage study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; de Boer, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, T.I.J.; Elders, L.A.M.; Burdorf, A. Influence of Health and Work on Early Retirement. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, P.; Carr, E.; Fleischmann, M.; Xue, B.; Stansfeld, S.A. The relationship between workplace psychosocial environment and retirement intentions and actual retirement: A systematic review. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 16, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.L.; Thorsen, S.V.; Larsen, M.; Sundstrup, E.; Boot, C.R.L.; Rugulies, R. Work factors facilitating working beyond state pension age: Prospective cohort study with register follow-up. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anxo, D.; Ericson, T.; Herbert, A. Beyond retirement: Who stays at work after the standard age of retirement? Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Oksanen, T.; Pentti, J.; Ervasti, J.; Head, J.; Stenholm, S.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Occupational class and working beyond the retirement age: A cohort study. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2017, 43, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zwaan, G.L.; Hengel, K.M.O.; Sewdas, R.; de Wind, A.; Steenbeek, R.; van der Beek, A.J.; Boot, C.R. The role of personal characteristics, work environment and context in working beyond retirement: A mixed-methods study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckerman, P.; Ilmakunnas, P. Do good working conditions make you work longer? Analyzing retirement decisions using linked survey and register data. J. Econ. Ageing 2020, 17, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, H.; Pohrt, A.; Rugulies, R.; Holtermann, A.; Hasselhorn, H.M. Does age modify the association between physical work demands and deterioration of self-rated general health? Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2017, 43, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.L.; Sundstrup, E. Study protocol for SeniorWorkingLife—Push and stay mechanisms for labour market participation among older workers. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.S.; Neumark, D. Barriers to later retirement for men: Physical challenges of work and increases in the full retirement age. Res. Aging 2018, 40, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengård, J.; Leineweber, C.; Virtanen, M.; Westerlund, H.; Wang, H.X. Do good psychosocial working conditions prolong working lives? Findings from a prospective study in Sweden. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.; Fleischmann, M.; Goldberg, M.; Kuh, D.; Murray, E.T.; Stafford, M.; Stansfeld, S.; Vahtera, J.; Xue, B.; Zaninotto, P.; et al. Occupational and educational inequalities in exit from employment at older ages: Evidence from seven prospective cohorts. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 75, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Breij, S.; Huisman, M.; Deeg, D.J.H. Educational differences in macro-level determinants of early exit from paid work: A multilevel analysis of 14 European countries. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 17, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, A.; Bodin, T.; Bronnum-Hansen, H.; Harber-Aschan, L.; Barr, B.; Bentley, L.; Liao, Q.; Jensen, N.K.; Andersen, I.; Chen, W.H.; et al. Inequalities in extending working lives beyond age 60 in Canada, Denmark, Sweden and England-By gender, level of education and health. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e234900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, T.; Chandola, T.; Laaksonen, M.; Martikainen, P. Socio-economic differences in retirement timing and participation in post-retirement employment in a context of a flexible pension age. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anxo, D.; Ericson, T.; Herbert, A.; Rönnmar, M. To Stay or Not to Stay. That Is the Question: Beyond Retirement: Stayers on the Labour Market; Linnaeus University: Växjö, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- SOU 2020:69; Äldre har Aldrig Varit Yngre—Allt Fler Kan Och Vill Arbeta Längre. Older People Have Never Been Younger—More and More People Can and Want to Work Longer; Report of the Delegation for Senior Workers. Betänkande av Delegationen för Senior Arbetskraft: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020.

- Fransson, A.; Söderberg, M. Hur Mycket Arbetar Seniorer? [How Much do Seniors Work?]; Rapport 7; Delegationen för Senior Arbetskraft: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden. Women and Men in Sweden 2018; Statistics Sweden: Örebro, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Leineweber, C.; Persson, V.; Hyde, M.; Theorell, T.; Westerlund, H. Cohort profile: The Swedish longitudinal occupational survey of health (SLOSH). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 691–692i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Sweden. Socioeconomisk Indelning (SEI) [Socio-Economic Classification] (MIS 1982:4); Statistics Sweden: Örebro, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Garefelt, J.; Richter, A.; Westerlund, H.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Sverke, M.; Kecklund, G. Work and sleep—A prospective study of psychosocial work factors, physical work factors, and work scheduling. Sleep 2015, 38, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadefors, R.; Nilsson, K.; Rylander, L.; Östergren, P.O.; Albin, M.; Ostergren, P.O. Occupation, gender and work-life exits: A Swedish population study. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1332–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aittomäki, A.; Lahelma, E.; Roos, E.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Martikainen, P. Gender differences in the association of age with physical workload and functioning. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cérdas, S.; Härenstam, A.; Johansson, G.; Nyberg, A. Development of job demands, decision authority and social support in industries with different gender composition—Sweden, 1991–2013. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, V.; Toivanen, S.; Leineweber, C.; Nyberg, A. Can a poor psychosocial work environment and insufficient organizational resources explain the higher risk of ill-health and sickness absence in human service occupations? Evidence from a Swedish national cohort. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, G.; Posso, M.; Arundel, C.; McDaid, C. Systematic review: Height-adjustable workstations to reduce sedentary behaviour in office-based workers. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, K.; Gran, J.M.; Kristensen, P.; Mehlum, I.S. Adult social position and sick leave: The mediating effect of physical workload. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2015, 41, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bulunuz, N. Noise Pollution in Turkish Elementary Schools: Evaluation of Noise Pollution Awareness and Sensitivity Training. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2014, 9, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scquizzato, T.; Gazzato, A.; Landoni, G.; Zangrillo, A. Assessment of noise levels in the intensive care unit using Apple Watch. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.A.; Dietz, A.S.; Lee, N.; I-Jeng, W.; Markowitz, J.; Wyskiel, R.M.; Yang, T.; Priebe, C.E.; Sapirstein, A.; Gurses, A.P.; et al. Sensor-based measurement of critical care nursing workload: Unobtrusive measures of nursing activity complement traditional task and patient level indicators of workload to predict perceived exertion. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e204819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, R.; Dellve, L.; Halleröd, B. Work despite poor health? A 14-year follow-up of how individual work accommodations are extending the time to retirement for workers with poor health conditions. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 9, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.C.; Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Ervasti, J.; Pentti, J.; Vahtera, J.; Stenholm, S. Trajectories of work ability from mid-life to pensionable age and their association with retirement timing. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viotti, S.; Martini, M.; Converso, D. Are there any job resources capable of moderating the effect of physical demands on work ability? A study among kindergarten teachers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2017, 23, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nobs (Nind) | All Blue-Collar Workers OR (95% CI) | Nobs (Nwomen) | Women OR (95% CI) | Nobs (Nmen) | Men OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDWT | 2543 (1649) | 1204 (796) | 1339 (853) | |||

| light (ref) | 939 | – | 435 | – | 504 | – |

| moderate | 763 | 1.15 (0.90; 1.48) | 372 | 1.24 (0.86; 1.78) | 391 | 1.04 (0.74; 1.47) |

| heavy | 841 | 1.45 (1.14; 1.85) ** | 397 | 1.53 (1.07; 2.20) * | 444 | 1.42 (1.02; 1.98) * |

| PHWE | 2518 (1631) | 1191 (787) | 1327 (844) | |||

| low-level (ref) | 686 | – | 414 | – | 272 | – |

| moderate | 1098 | 1.12 (0.88; 1.43) | 642 | 1.08 (0.78; 1.49) | 456 | 1.20 (0.82; 1.76) |

| high-level | 734 | 1.41 (1.07; 1.86) * | 135 | 2.01 (1.19; 3.41) * | 599 | 1.42 (0.98; 2.06) † |

| Nobs (Nind) | All White-Collar Workers OR (95% CI) | Nobs (Nwomen) | Women OR (95% CI) | Nobs (Nmen) | Men OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDWT | 5700 (3448) | 0.82 (0.72; 0.94) ** | 3443 (2057) | 0.84 (0.70; 1.00) † | 2257 (1391) | 0.78 (0.63; 0.96) * |

| PHWE | 5658 (3437) | 1.09 (0.95; 1.24) | 3411 (2048) | 1.10 (0.92; 1.31) | 2247 (1389) | 1.04 (0.84; 1.30) |

| All Blue-Collar Workers | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| PDWT | |||

| Main effect: light (ref) | |||

| – | – | – | |

| moderate | 0.97 (0.45; 2.09) | 1.47 (0.43; 5.03) | 0.78 (0.29; 2.13) |

| heavy | 1.70 (0.83; 3.49) | 4.40 (1.47; 13.22) ** | 0.91 (0.34; 2.45) |

| Interaction with linear age: age#light (ref) | |||

| – | – | – | |

| moderate | 1.04 (0.89; 1.22) | 0.97 (0.74; 1.28) | 1.06 (0.87; 1.30) |

| heavy | 0.96 (0.83; 1.12) | 0.77 (0.61; 0.99) * | 1.10 (0.90; 1.36) |

| PHWE | |||

| Main effect: low-level (ref) | |||

| – | – | – | |

| moderate | 0.65 (0.31; 1.36) | 0.98 (0.35; 2.74) | 0.44 (0.15; 1.33) |

| high-level | 0.94 (0.43; 2.06) | 2.74 (0.70; 10.67) | 0.45 (0.16; 1.28) |

| Interaction with linear age: age#low-level (ref) | |||

| – | – | – | |

| moderate | 1.12 (0.96; 1.31) | 1.02 (0.81; 1.28) | 1.21 (0.98; 1.51) † |

| high-level | 1.09 (0.92; 1.28) | 0.91 (0.66; 1.26) | 1.26 (1.02; 1.56) * |

| All White-Collar Workers | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| PDWT | |||

| main effect | 0.53 (0.36; 0.79) ** | 0.57 (0.34; 0.97) * | 0.49 (0.27; 0.89) * |

| interaction with linear age | 1.10 (1.01; 1.19) * | 1.08 (0.97; 1.21) | 1.10 (0.98; 1.24) |

| PHWE | |||

| main effect | 0.63 (0.43; 0.93) * | 0.47 (0.28; 0.79) ** | 1.12 (0.62; 2.04) |

| interaction with linear age | 1.13 (1.04; 1.22) ** | 1.20 (1.08; 1.34) *** | 0.99 (0.87; 1.11) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stengård, J.; Virtanen, M.; Leineweber, C.; Westerlund, H.; Wang, H.-X. The Implication of Physically Demanding and Hazardous Work on Retirement Timing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138123

Stengård J, Virtanen M, Leineweber C, Westerlund H, Wang H-X. The Implication of Physically Demanding and Hazardous Work on Retirement Timing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138123

Chicago/Turabian StyleStengård, Johanna, Marianna Virtanen, Constanze Leineweber, Hugo Westerlund, and Hui-Xin Wang. 2022. "The Implication of Physically Demanding and Hazardous Work on Retirement Timing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138123

APA StyleStengård, J., Virtanen, M., Leineweber, C., Westerlund, H., & Wang, H.-X. (2022). The Implication of Physically Demanding and Hazardous Work on Retirement Timing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138123