Frequency, Types, and Manifestations of Partner Sexual Violence, Non-Partner Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment: A Population Study in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Key Definitions and Limitations

1.2. Frequencies of Different Forms of Sexual Violence

1.3. Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated with Different Forms of Sexual Violence

1.4. Formal and Informal Reporting of Sexual Violence

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Variables

- (a)

- Partner or ex-partner Sexual Violence (PSV).

- (b)

- Non-Partner Sexual Violence (NPSV).

- (c)

- Sexual Harassment (SH).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Partner Sexual Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence

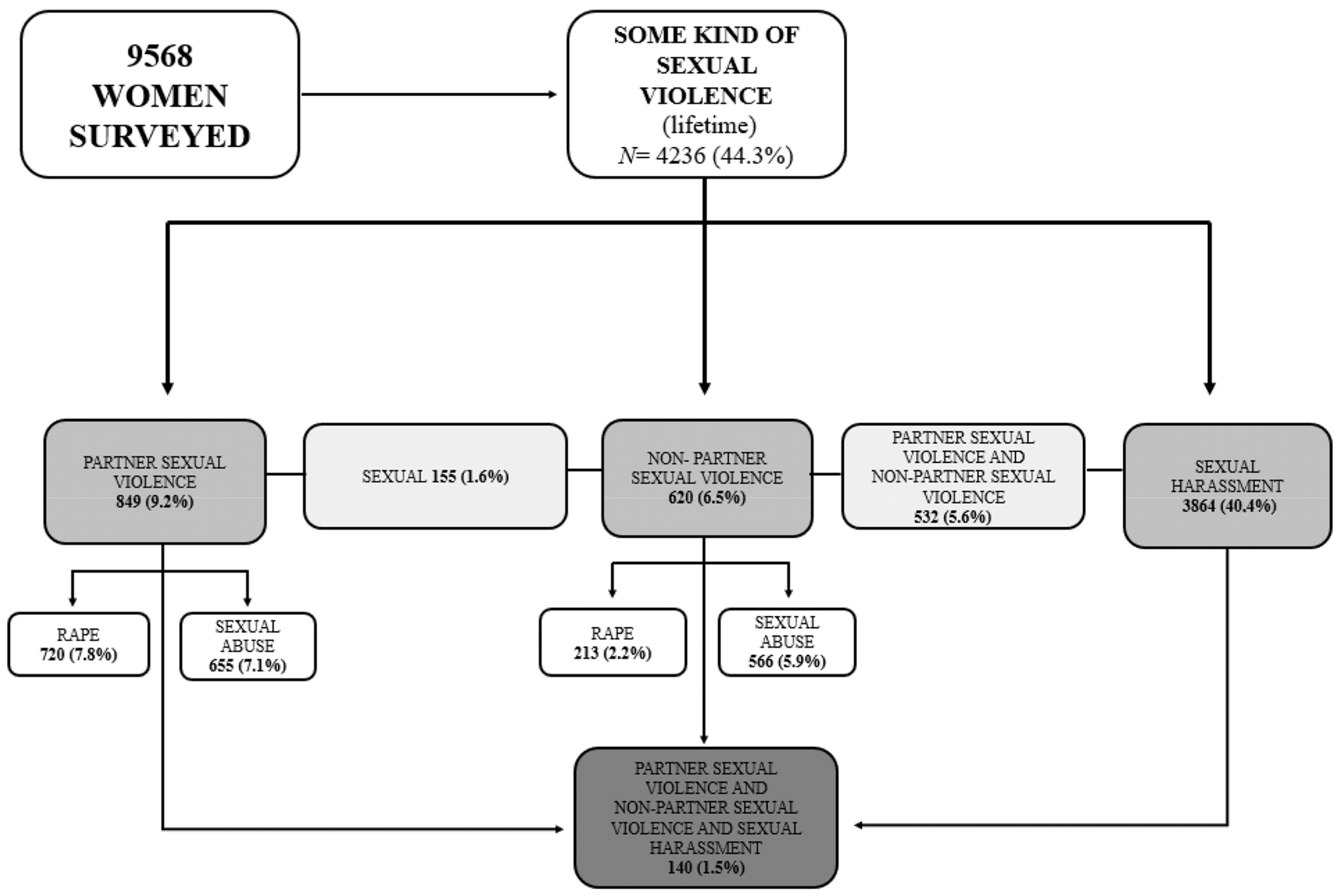

3.1.1. Frequency

3.1.2. Characteristics of Women Associated with Partner Sexual Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence

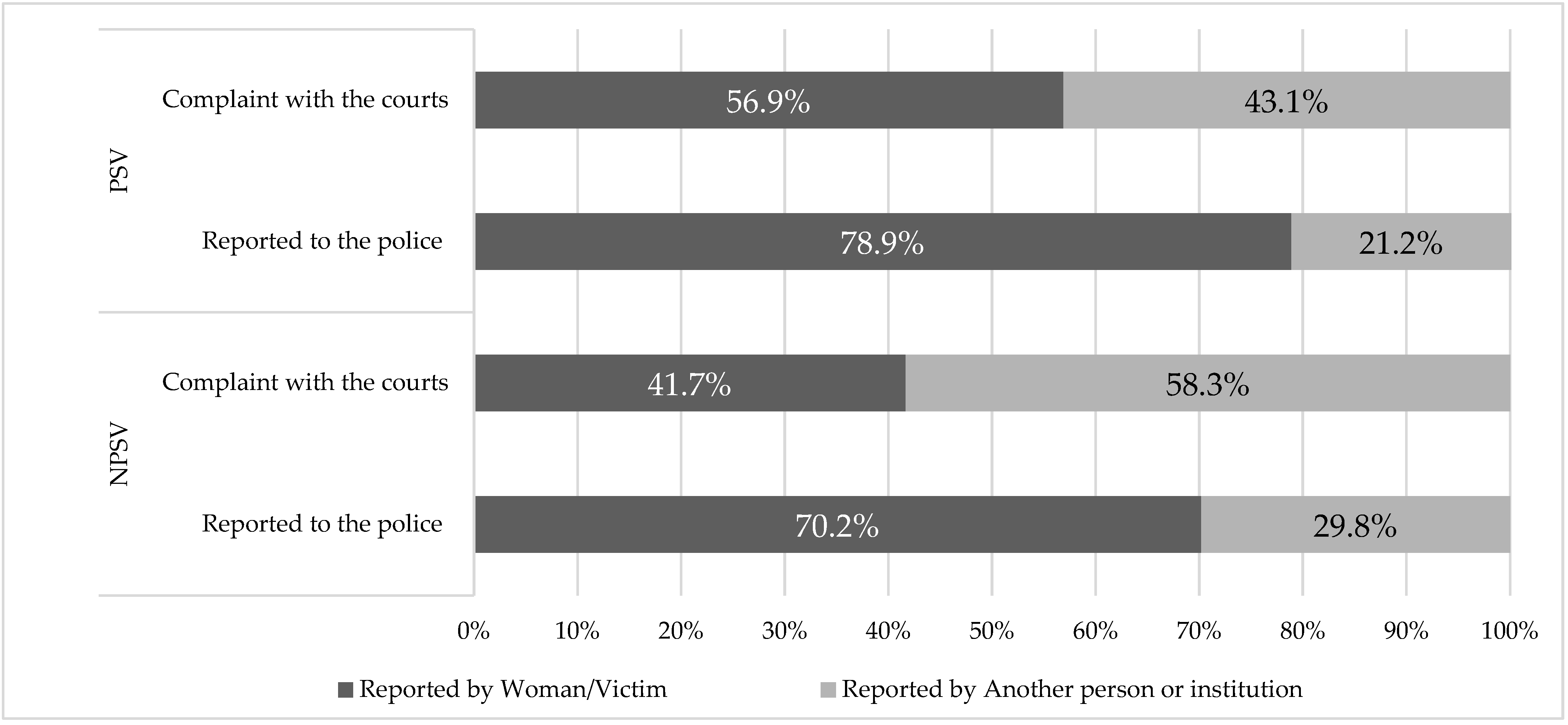

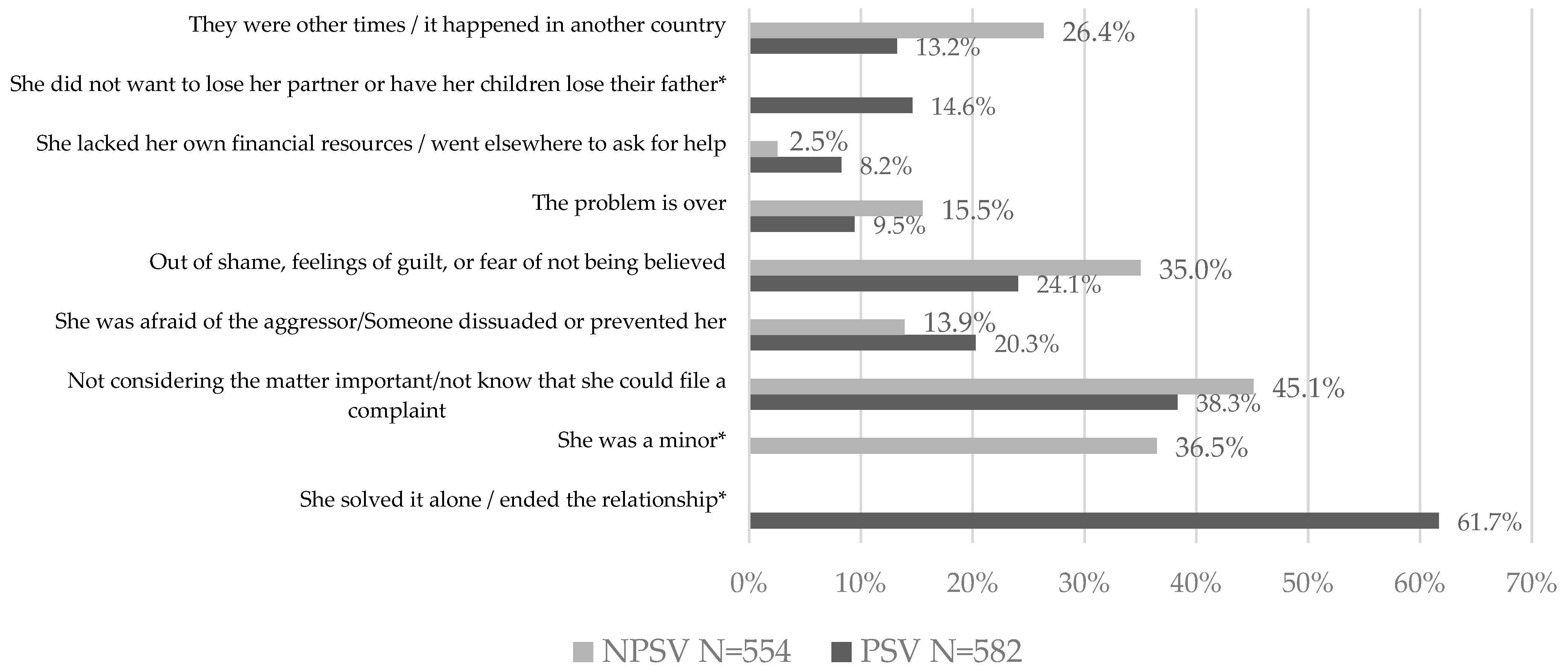

3.1.3. Prevalence for Filing Police Reports or Complaint and Reasons for Not Filing

3.2. Sexual Harassment

3.2.1. Frequency and Types of SH

3.2.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated with SH

3.2.3. Disclosure to Other People and Institutions

3.2.4. Characteristics of Women Who Do Not Talk about SH

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Partner Sexual Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence | ||

| 1 | You have been forced to have sexual relations by being threatened, held, or hurt in some way. By sexual relations we mean vaginal or anal penetration by the penis or by an object or objects, or oral sex. | Rape |

| 2 | You have been forced to have sexual relations when you were incapable of refusing because you were under the influence of alcohol or drugs. | |

| 3 | You have had sexual relations without wanting to because you were afraid of what might happen if you refused. | |

| 4 | You have been coerced into having sexual relations when you did not want to. | |

| 5 | Attempts have been made to coerce you into having sexual relations against your will, without success. | Sexual assault/abuse |

| 6 | Your private parts—genitals or breast(s)—have been touched or you have been touched sexually in some other way when you did not want this to happen. | |

| 7 | You have been made to touch another person’s private parts—genitals or breast(s)—or forced to touch them sexually in some other way when you did not want to do so. | |

| 8 | You have been forced to engage in some other practice of a sexual nature that has not already been mentioned. | |

| Sexual Harassment | ||

| 1 | You have been subjected at some point to staring or leering that made you feel intimidated | Intimidation |

| 2 | Someone has shown or sent you sexually explicit images or photos that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated | Exhibitionism |

| 3 | Someone has exposed themselves to you indecently | |

| 4 | Someone has forced you to view pornographic material against your will | |

| 5 | You have received sexual jokes or offensive comments about your body or your private life | Inappropriate content |

| 6 | You have received inappropriate, humiliating, intimidating or offensive insinuations on online social media such as Facebook, Instagram or Twitter | |

| 7 | You have received inappropriate sexually explicit emails, WhatsApp messages or text messages that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated | |

| 8 | You have received inappropriate suggestions for going on a date or engaging in some activity of a sexual nature that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated | Inappropriate suggestions |

| 9 | You have been subjected to unwanted physical contact, such as standing unnecessarily close to you, touching parts of your body, kisses/embraces, or anything else that you did not want | Inappropriate contact |

| 10 | Someone has threatened you with unpleasant consequences in your job, such as dismissal, for example, if you rejected proposals or sexual advances | Workplace |

| 11 | You have experienced other similar types of behavior with sexual connotations that made you feel offended, humiliated or intimidated and that have not already been mentioned | Other |

References

- World Health Organization; Pan American Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432 (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/full_en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Abrahams, N.; Devries, K.; Watts, C.; Pallitto, C.; Petzold, M.; Shamu, S.; GarcÍa-Moreno, C. Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: A systematic review. Lancet 2014, 383, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell-Gray, M.E.; Messing, J.T.; Baldwin-White, A. Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: A Review of Terms, Definitions, and Prevalence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015, 16, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, L.C.; Stewart, D.E.; Vigod, S.N. Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: An Often Overlooked Problem. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Petzold, M.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Lim, H.; Bacchus, L.J.; Engelll, R.E.; Rosenfeld, L.; et al. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science 2013, 340, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Montero-Piñar, I.; Vives-Cases, C.; Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Plazaola-Castaño, J.; Jiménez-Gutiérrez, E.; Fuentes-Pujol, M.; Rohlfs-Barbosa, I.; Blanco-Prieto, P.; et al. G6 for the Study of Gender Violence in Spain, Prevalence of intimate partner violence in Spain: A national cross-sectional survey in primary care. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvid, P.; Saing, R. If I Don’t Allow Him to Have Sex With Me, Our Relationship Will Be Broken’: Rape, Sexual Coercion, and Sexual Compliance Within Marriage in Rural Cambodia. Violence Against Women 2021, 28, 1587–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Faitakis, M.; Cheema, H. A comparative profile of intimate partner sexual violence. J. Sex. Aggress. 2021, 27, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krienert, J.L.; Walsh, J.A. An Examination of Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: Comparing Marital and Nonmarital Incidents Employing NIBRS Data, 2008–2012. Partn. Abus. 2018, 9, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. In Working for Health and Growth: Investing in the Health Workforce; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Spinel, M.; White, C.; Ford, K.; Swan, S. A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, K.; Tarzia, L. Identification and Management of Domestic and Sexual Violence in Primary Care in the #MeToo Era: An Update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, M.R.; Dey, D.; Crainiceanu, C.; Dredze, M. #MeToo and Google Inquiries Into Sexual Violence: A Hashtag Campaign Can Sustain Information Seeking. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, 9857–9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women. Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Cotter, A. Intimate Partner Violence in Canada, 2018: An Overview; Statistics Canada, Minister of Industry: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00003-eng.htm (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against women: An EU-wide survey. Main results. In Publications Office of the European Union; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Luxembourg, 2014; Available online: http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results-apr14_en.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Smith, S.G.; Zhang, X.; Basile, K.C.; Merrick, M.T.; Wang, J.; Kresnow, M.J.; Chen, J. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief-Updated Release; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, Georgia, 2018. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60893 (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Kearl, H. The Facts Behind the #Metoo Movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. 2018. Available online: https://ncvc.dspacedirect.org/handle/20.500.11990/789 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Du Mont, J.; Woldeyohannes, M.; Macdonald, S.; Kosa, D.; Turner, L. A comparison of intimate partner and other sexual assault survivors’ use of different types of specialized hospital-based violence services. BMC Womens Health 2017, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ali, T.S.; Asad, N.; Mogren, I.; Krantz, G. Intimate partner violence in urban Pakistan: Prevalence, frequency, and risk factors. Int. J. Womens Health 2011, 3, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, E.N.; Högberg, U.; Hakimi, M.; Ellsberg, M.C.; Emmelin, M. Behind the silence of harmony: Risk factors for physical and sexual violence among women in rural Indonesia. BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukanangana, F.; Moyo, S.; Zvoushe, A.; Rusinga, O. Gender based violence and its effects on women’s reproductive health: The case of Hatcliffe, Harare, Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2014, 18, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Black, M.C.; Basile, K.C.; Breiding, M.J.; Ryan, G.W. Prevalence of Sexual Violence against Women in 23 States and Two U.S. Territories, BRFSS 2005. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiding, M.J. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Report. Surveill. Summ. 2014, 63, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marcantonio, T.L.; Weese, J.; Willis, M. Rates of Forced Sexual Experiences Among High School Students From 2001 to 2019. J. Interpers. Violence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondestam, F.; Lundqvist, M. Sexual harassment in higher education—A systematic review. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2020, 10, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.B.; Martin, S.L. Sexual Harassment of College and University Students: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 22, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APPG for UN Women. Prevalence and Reporting of Sexual Harassment in UK Public Spaces. A Report by the APPG for UN Women; APPG for UN Women: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.unwomenuk.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/APPG-UN-Women-Sexual-Harassment-Report_Updated.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/gho-documents/world-health-statistic-reports/world-health-statistics-2015.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Holmberg, S.; Lewenhagen, L. Reported and Cleared Rapes in Europe. Difficulties of International Comparisons; Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.bra.se/download/18.7d27ebd916ea64de5306c65f/1601393665407/2020_13_Reported_and_cleared_rapes_in_Europe.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Government Office against Gender-Based Violence. Macro-Survey on Violence against Women; Ministry of Equality: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/en/violenciaEnCifras/macroencuesta2015/Macroencuesta2019/home.htm (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Statistical Division Publications of the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Guidelines for the Production of Statistics on Violence against Women Statistical Surveys; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/docs/Guidelines_Statistics_VAW.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Council of Europe. Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (CETS No. 210); Council of Europe: Istanbul, Turkey, 2011; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168008482e (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Meseguer-Santamaría, M.-L.; Sánchez-Alberola, F.; Vargas-Vargas, M. Intimate partner violence againstwomen with disabilities in Spain: A public health problem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Barbero, B.; Vives-Cases, C.; Otero-García, L.; Muntaner, C.; Torrubiano-Domínguez, J.; O'Campo, Y.P. Intimate partner violence among women in Spain: The impact of regional-level male unemployment and income inequality. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Barbero, B.; Barón, N.; Vives-Cases, C. Prevalence, associated factors and health impact of intimate partner violence against women in different life stages. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubovich, A.R.; Stöckl, H.; Murray, J.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Steinert, J.I.; Glavin, C.E.Y.; Humphreys, D.K. Risk and Protective Factors for Intimate Partner Violence against Women: Systematic Review and Meta-analyses of Prospective-Longitudinal Studies. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, M.; Tartaglia, S.; De Piccoli, N. Assessing Rape Myth Acceptance: A Contribution to Italian Validation of the Measure for Assessing Subtle Rape Myth (SRMA-IT). Sex. Abus. 2021, 34, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Rødel, A.M.; Leth, P.M.; Astrup, B.S. Stranger rape; distinctions between the typical rape type and other types of rape. A study based on data from Center for Victims of Sexual Assault. J. Forensic. Leg. Med. 2021, 80, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Office against Gender-based Violence. The Social Perception of Sexual Violence; Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with Parliament and Equality: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/en/violenciaEnCifras/estudios/colecciones/pdf/Libro_25_Violencia_Sexual_English.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Apatinga, G.A.; Tenkorang, E.Y. Determinants of Sexual Violence against Married Women: Qualitative Evidence from Ghana. Sex. Abus. 2020, 33, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Plazaola-Castaño, J.; Alvarez-Kindelán, M.; Palomo-Pinto, M.; Arnalte-Barrera, M.; Bonet-Pla, A.; De Santiago-Hernando, M.L.; Herranz-Torrubiano, A.; Garralón-Ruiz, L.M. Sociodemographic associations of physical, emotional, and sexual intimate partner violence in Spanish women. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 16, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, C.; Myers, J.S.; Riggle, C.; Lacy, M. From margins to mainstream: Social media as a tool for campus sexual violence activism. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2016, 9, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.C.; Breiding, M.J.; Smith, S.G. Disability and Risk of Recent Sexual Violence in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, S.; Cotter, A. Self-Reported Sexual Assault in Canada 2014; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14842-eng.pdf?st=LOkprFiP (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Oram, S. Sexual violence and mental health. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 28, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, M.D.C.; Herrera, A.; Expósito, F. To confront versus not to confront: Women’s perception of sexual harassment. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Grace, R. Social desirability and sexual offenders: A review. Sex. Abus. 2008, 20, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, R.T.; Feder, K.A. The public health approach to preventing sexual violence. In Sexual Violence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

| Sexual Violence in Partnerships (PSV) N = 849 (9.23%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR [95% CI] * | aOR [95% CI] ** | |

| Age | |||

| ≥66 | 132 (6.16%) | 1 | 1 |

| 46–65 | 297 (9.51%) | 1.56 [1.25–1.95] | 1.67 [1.14–2.44] |

| 26–45 | 311 (10.34%) | 1.82 [1.47–2.27] | 2.56 [1.66–3.96] |

| 16–25 | 109 (11.76%) | 2.10 [1.58–2.77] | 3.44 [1.86–6.29] |

| Size of municipality | |||

| 0–10,000 | 154 (8.65%) | 1 | |

| 10,001–100,000 | 344 (9.56%) | 1.10 [0.90–1.34] | |

| ≥100,001 | 352 (9.21%) | 1.13 [0.93–1.39] | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Primary or less | 86 (8.89%) | 1 | |

| Secondary (high school) | 320 (8.89%) | 1.36 [1.05–1.79] | |

| Higher (university) | 86 (5.98%) | 0.94 [0.68-1.31] | |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 132 (10.39%) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 256 (8.28%) | 0.73 [0.58–0.91] | 0.69 [0.52–0.91] |

| ≥3 | 457 (9.46%) | 0.79 [0.65–0.98] | 0.52 [0.38–0.72] |

| Having children | |||

| No | 216 (8.93%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 629 (9.70%) | 1.02 [0.86–1.20] | 1.80 [1.36–2.41] |

| Country of birth | |||

| Spain | 756 (8.91%) | 1 | |

| Other | 93 (12.99%) | 1.52 [1.20–1.91] | |

| Employment situation | |||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 222 (9.09%) | 1 | 1 |

| Employed | 429 (10.17%) | 1.21 [1.02–1.44] | 1.45 [1.15–1.84] |

| Retired | 152 (7.44%) | 0.82 [0.65–1.02] | 1.18 [0.84–1.68] |

| Student | 42 (9.29%) | 1.13 [0.78–1.60] | 1.60 [0.83–2.98] |

| Level of family income | |||

| >3000€/month | 52 (7.17%) | 1 | 1 |

| 1801–3000€/month | 144 (8.05%) | 1.10 [0.79–1.56] | 1.08 [0.76–1.55] |

| 901–1800€/month | 238 (10.30%) | 1.50 [1.10–2.10] | 1.70 [1.22–2.42] |

| 301–900€/month | 159 (13.85%) | 2.15 [1.55–3.05] | 2.70 [1.86–3.99] |

| ≤300€/month | 14 (11.86%) | 1.65 [0.91-2.87] | 2.03 [1.09–3.66] |

| Internet use | |||

| No | 125 (6.88%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 719 (9.74%) | 1.45 [1.19–1.78] | 1.36 [1.00-1.87] |

| Degree of disability ≥ 33% | |||

| No | 770 (8.69%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 79 (1.34%) | 1.78 [1.38–2.28] | 2.34 [1.70–3.16] |

| Sexual Violence Non–Partnerships (NPSV) N = 620 (6.48%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR [95% CI] * | aOR [95% CI] ** | |

| Age | |||

| ≥66 | 56 (2.55%) | 1 | 1 |

| 46–65 | 198 (6.21%) | 2.46 [1.82–3.39] | 1.50 [0.98–2.32] |

| 26–45 | 249 (8.13%) | 3.19 [2.38–4.37] | 1.86 [1.20–2.94] |

| 16–25 | 117 (10.48%) | 4.31 [3.08–6.10] | 2.85 [1.69–4.87] |

| Size of municipality | |||

| 0–10,000 | 105 (5.60%) | 1 | |

| 10,001–100,000 | 287 (7.68%) | 1.25 [0.98–1.60] | |

| ≥100,001 | 229 (5.79%) | 1.45 [1.14–1.86] | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Primary or less | 35 (2.84%) | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary (high school) | 238 (6.60%) | 2.55 [1.76–3.83] | 1.51 [1.02–2.28] |

| Higher (university) | 115 (7.99%) | 3.05 [2.04–4.69] | 2.31 [1.53–3.56] |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 85 (6.29%) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 195 (6.20%) | 1.04 [0.79–1.38] | 0.78 [0.56–1.10] |

| ≥3 | 337 (6.66%) | 1.06 [0.82–1.39] | 0.64 [0.46–0.90] |

| Having children | |||

| No | 257 (9.30%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 363 (5.34%) | 0.54 [0.46–0.65] | |

| Country of birth | |||

| Spain | 556 (6.30%) | 1 | |

| Other | 64 (8.58%) | 1.21 [0.90–1.60] | |

| Employment situation | |||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 158 (6.30%) | 1 | |

| Employed | 329 (7.65%) | 1.22 [1.00–1.50] | |

| Retired | 79 (3.73%) | 0.57 [0.43–0.76] | |

| Student | 52 (8.78%) | 1.44 [1.01–2.01] | |

| Level of family income | |||

| >3000€/month | 9 (7.20%) | 1 | |

| 1801–3000€/month | 76 (10.38%) | 0.74 [0.55–1.01] | |

| 901–1800€/month | 136 (7.47%) | 0.53 [0.39–0.72] | |

| 301–900€/month | 136 (5.72%) | 0.56 [0.39–0.80] | |

| ≤300€/month | 71 (5.95%) | 0.75 [0.39–1.35] | |

| Internet use | |||

| No | 31 (1.66%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 589 (7.65%) | 4.99 [3.47–7.48] | 2.24 [1.36–3.80] |

| Degree of disability ≥ 33% | |||

| No | 563 (90.81%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 57 (9.19%) | 1.77 [1.31–2.34] | 1.99 [1.35–2.86] |

| N = 3864 n (%) | OR [95% CI] * | aOR [95% CI] ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≥66 | 672 (30.55%) | 1 | 1 |

| 46–65 | 1502 (47.11%) | 2.29 [2.02–2.60] | 1.43 [1.12–1.82] |

| 26–45 | 1209 (39.46%) | 3.50 [3.08–3.97] | 1.97 [1.50–2.58] |

| 16–25 | 481 (43.10%) | 6.08 [5.18–7.16] | 3.18 [2.22–4.54] |

| Size of municipality | |||

| 0–10,000 | 667 (35.59%) | 1 | 1 |

| 10,001–100,000 | 1731 (46.32%) | 1.34 [1.19–1.50] | 1.16 [1.00–1.35] |

| ≥100,001 | 1466 (37.05%) | 1.54 [1.37–1.73] | 1.35 [1.15–1.57] |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Primary or less | 470 (20.29%) | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary (high school) | 2185 (43.37%) | 3.13 [2.79–3.52] | 1.85 [1.54–2.24] |

| Higher (university) | 1204 (54.50%) | 4.72 [4.13–5.40] | 2.84 [2.28–3.54] |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 442 (32.72%) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1198 (38.07%) | 1.30 [1.13–1.49] | 1.03 [0.86–1.25] |

| ≥3 | 2221 (43.89%) | 1.59 [1.40–1.82] | 0.77 [0.64–0.94] |

| Having children | |||

| No | 1487 (53.80%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 2377 (34.94%) | 0.43 [0.39–0.47] | |

| Country of birth | |||

| Spain | 3530 (40.01%) | 1 | |

| Other | 334 (44.77%) | 1.09 [0.94–1.26] | |

| Employment situation | |||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 880 (35.09%) | 1 | 1 |

| Employed | 2006 (46.64%) | 1.55 [1.40–1.72] | 1.12 [0.97–1.29] |

| Retired | 578 (27.32%) | 0.65 [0.58–0.74] | 1.14 [0.91–1.43] |

| Student | 378 (63.85%) | 3.56 [2.95–4.31] | 2.44 [1.64–3.66] |

| Level of family income | |||

| >3000€/month | 418 (57.10%) | 1 | 1 |

| 1801–3000€/month | 840 (46.15%) | 0.64 [0.46–0.89] | 1.10 [0.76–1.61] |

| 901–1800€/month | 886 (37.29%) | 0.97 [0.71–1.33] | 1.16 [0.81–1.67] |

| 301–900€/month | 333 (27.91%) | 1.32 [0.96–1.82] | 1.16 [0.81–1.68] |

| ≤300€/month | 50 (40.00%) | 2.20 [1.57–3.10] | 1.57 [1.06–2.34] |

| Internet use | |||

| No | 312 (16.75%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 3551 (46.10%) | 4.30 [3.78–4.92] | 1.91 [1.53–2.38] |

| Degree of disability ≥ 33% | |||

| No | 3636 (40.39%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 224 (40.29%) | 1.04 [0.87–1.23] | 1.61 [1.27–2.03] |

| N = 2304 n (%) | |

|---|---|

| A family member or close friend | 2113 (91.7%) |

| A fellow worker or student | 329 (14.3%) |

| Reported to the police or the courts to file a complaint | 96 (4.2%) |

| Professional service (medical, psychological, social, or legal) | 79 (3.4%) |

| Told about it on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram…) | 23 (1.0%) |

| Not Talk about SH n = 1529 | Talk about SH n = 2335 | OR [95% CI] * | aOR [95% CI] ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| ≥ 66 | 250 (16.35%) | 232 (9.94%) | 1 | 1 |

| 46–65 | 532 (34.79%) | 677 (28.99%) | 1.45 [1.19–1.78] | 1.43 [1.05–1.95] |

| 26–45 | 554 (36.23%) | 947 (40.56%) | 1.93 [1.57–2.38] | 1.76 [1.29–2.43] |

| 16–25 | 193 (12.62%) | 479 (20.51%) | 2.78 [2.16–3.59] | 2.34 [1.55–3.55] |

| Size of municipality | ||||

| 0–10,000 | 251 (16.42%) | 416 (17.82%) | 1 | |

| 10,001–100,000 | 571 (37.34%) | 896 (38.37%) | 1.05 [0.87–1.26] | |

| ≥100,001 | 707 (46.24%) | 1023 (43.81%) | 1.15 [0.95–1.39] | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Primary or less | 398 (26.03%) | 806 (34.52%) | 1 | |

| Secondary (high school) | 886 (57.95%) | 1299 (55.63%) | 1.39 [1.20–1.62] | |

| Higher (university) | 244 (15.96%) | 226 (9.68%) | 2.32 [1.85–2.90] | |

| Country of birth | ||||

| Spain | 1390 (90.91%) | 2139 (91.61%) | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 139 (9.09%) | 196 (8.39%) | 1.29 [1.02–1.62] | 1.46 [1.07–1.99] |

| Employment situation | ||||

| Unemployed/Housewife | 370 (24.20%) | 510 (21.84%) | 1 | |

| Employed | 764 (49.97%) | 1242 (53.19%) | 0.82 [0.70–0.96] | |

| Retired | 283 (18.51%) | 295 (12.63%) | 1.32 [1.07–1.64] | |

| Student | 107 (7.00%) | 272 (11.65%) | 0.55 [0.42–0.71] | |

| Level of family income | ||||

| ≤300€/month | 15 (0.98%) | 35 (1.50%) | 1 | |

| 301–900€/month | 159 (10.40%) | 174 (7.45%) | 1.38 [0.80–2.41] | |

| 901–1800€/month | 366 (23.94%) | 520 (22.27%) | 1.11 [0.67–1.89] | |

| 1801–3000€/month | 319 (20.86%) | 521 (22.31%) | 0.96 [0.57–1.63] | |

| >3000€/month | 140 (9.16%) | 278 (11.91%) | 0.78 [0.46–1.35] | |

| Internet use | ||||

| Yes | 173 (11.31%) | 139 (5.95%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1356 (88.69%) | 2195 (94.00%) | 2.16 [1.69–2.75] | 1.60 [1.11–2.31] |

| Trusted person | ||||

| Yes | 1395 (91.24%) | 2231 (95.55%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 129 (8.44%) | 100 (4.28%) | 2.07 [1.56–2.77] | 1.61 [1.12–2.33] |

| Religiosity | ||||

| No | 513 (33.55%) | 1046 (44.80%) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 960 (62.79%) | 1199 (51.35%) | 1.55 [1.35–1.79] | 1.26 [1.04–1.51] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastor-Moreno, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Sordo, L.; Henares-Montiel, J. Frequency, Types, and Manifestations of Partner Sexual Violence, Non-Partner Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment: A Population Study in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138108

Pastor-Moreno G, Ruiz-Pérez I, Sordo L, Henares-Montiel J. Frequency, Types, and Manifestations of Partner Sexual Violence, Non-Partner Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment: A Population Study in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):8108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138108

Chicago/Turabian StylePastor-Moreno, Guadalupe, Isabel Ruiz-Pérez, Luis Sordo, and Jesús Henares-Montiel. 2022. "Frequency, Types, and Manifestations of Partner Sexual Violence, Non-Partner Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment: A Population Study in Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 8108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138108

APA StylePastor-Moreno, G., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Sordo, L., & Henares-Montiel, J. (2022). Frequency, Types, and Manifestations of Partner Sexual Violence, Non-Partner Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment: A Population Study in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138108