Development of a Quantitative Instrument to Elicit Patient Preferences for Person-Centered Dementia Care Stage 1: A Formative Qualitative Study to Identify Patient Relevant Criteria for Experimental Design of an Analytic Hierarchy Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

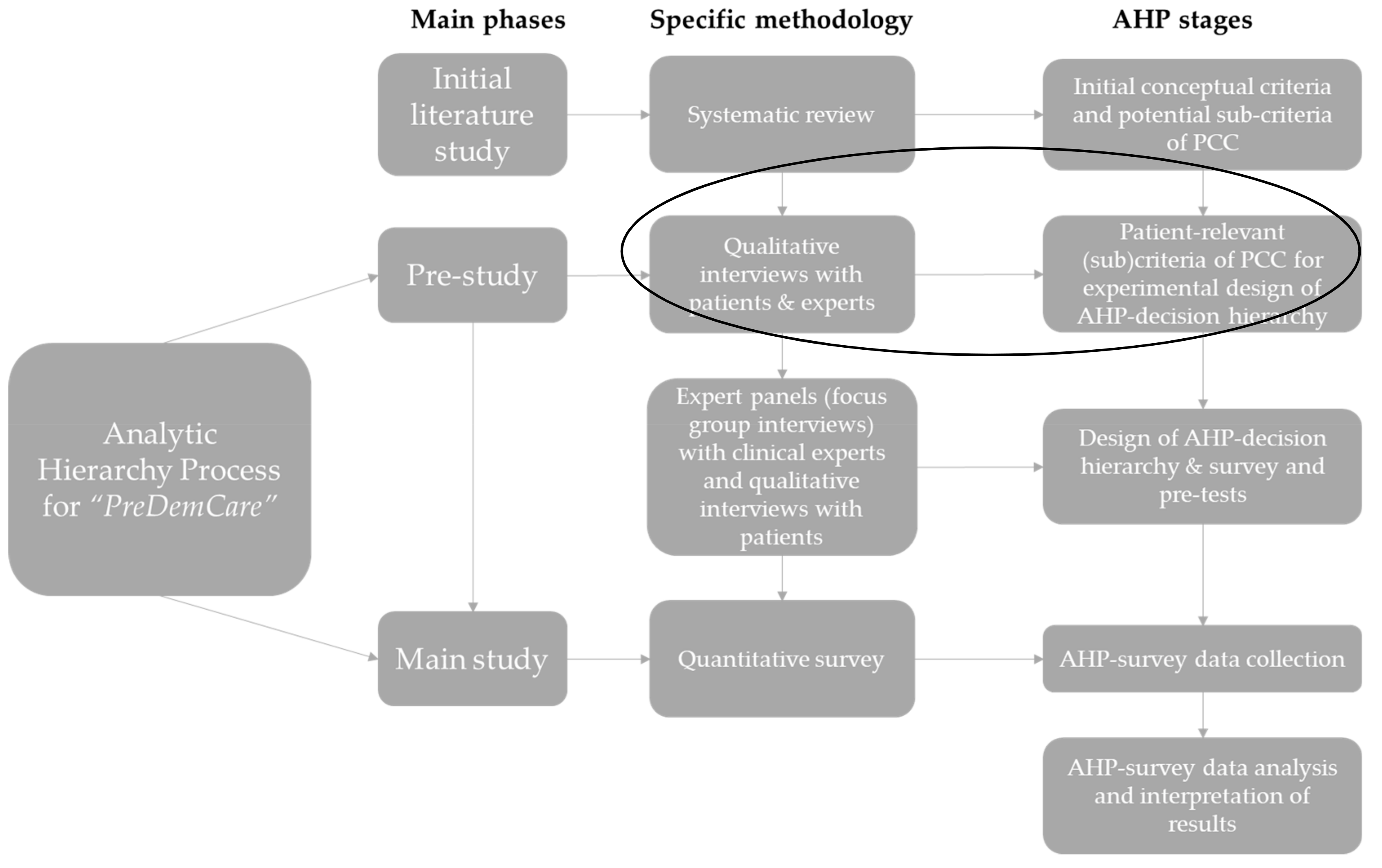

2. Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Theoretical Perspective

2.2.2. Initial Systematic Literature Review

2.3. Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

2.4. Sampling Strategy and Process

2.5. Sampling Adequacy

2.6. Sample

2.7. Ethical Review

2.8. Data Collection Methods, Sources and Instruments

2.9. Data Processing and Analysis

2.9.1. Card Games

2.9.2. Audio Recordings

3. Results

3.1. Patient-Relevant Criteria

3.2. New Criteria of PCC

3.3. Plausible Sub-Criteria

3.4. Overlapping of Criteria

3.5. Wording and Comprehensibility

3.6. Other Observations

3.6.1. Reactions by PlwD

3.6.2. Interaction with Informal CGs

3.6.3. Explorative vs. Card-Game Responses

3.6.4. Setting

3.6.5. COVID-19

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016—Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the Future; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Bryce, R.; Ferri, C. World Alzheimer Report 2011—The Benefits of Early Diagnosis and Intervention; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia Care Practice Recommendations. Available online: https://www.alz.org/professionals/professional-providers/dementia_care_practice_recommendations (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers (NG97). NICE Guideline; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Nationella Riktlinjer för Vård Och Omsorg Vid Demenssjukdom. Stöd för Styrning Och Ledning; The National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia; NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dely, H.; Verschraegen, J.; Setyaert, J. You and Me, Together We Are Human—A Reference Framework for Quality of Life, Housing and Care for People with Dementia; Flanders Centre of Expertise on Dementia: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan, E.; Bopp-Kistler, I.; Buerge, M.; Fischlin, R.; Georgescu, D.; Giardini, U.; Hatzinger, M.; Hemmeter, U.; Justiniano, I.; Kressig, R.W.; et al. Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Behavioralen und Psychologischen Symptome der Demenz (BPSD). Praxis 2014, 103, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danish Health Authority. Forebyggelse og Behandling af Adfærdsmæssige og Psykiske Symptomer hos Personer Med Demens. National Klinisk Retningslinje; Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Dementia Plan 2020—A More Dementia-Friendly Society; Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2015.

- Morgan, S.; Yoder, L. A concept analysis of person-centered care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T.; Bredin, K. Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. 1992, 12, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First (Rethinking Ageing Series); Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lepper, S.; Rädke, A.; Wehrmann, H.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Preferences of Cognitively Impaired Patients and Patients Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Patient Preference Studies. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, H.; Michalowsky, B.; Lepper, S.; Mohr, W.; Raedke, A.; Hoffmann, W. Priorities and Preferences of People Living with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment—A Systematic Review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; Chang, H.R.; Liu, M.F.; Chien, H.W.; Tang, L.Y.; Chan, S.Y.; Liu, S.H.; John, S.; Traynor, V. Decision-Making in People With Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Narrative Review of Decision-Making Tools. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2056–2062.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison Dening, K.; King, M.; Jones, L.; Vickerstaff, V.; Sampson, E.L. Correction: Advance Care Planning in Dementia: Do Family Carers Know the Treatment Preferences of People with Early Dementia? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Haitsma, K.; Curyto, K.; Spector, A.; Towsley, G.; Kleban, M.; Carpenter, B.; Ruckdeschel, K.; Feldman, P.H.; Koren, M.J. The preferences for everyday living inventory: Scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A. Ohne Patientenpräferenzen kein sinnvoller Wettbewerb. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2017, 114, A 1584–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewoud, S.; Van Exel, N.J.A.; Bobinac, A.; Berg, M.; Huijsman, R.; Stolk, E.A. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? Measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1941–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A.; Zweifel, P.; Johnson, F.R. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: An overview. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. Der Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): Eine Methode zur Entscheidungsunterstützung im Gesundheitswesen. Pharm. Ger. Res. Artic. 2013, 11, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danner, M.; Vennedey, V.; Hiligsmann, M.; Fauser, S.; Gross, C.; Stock, S. How Well Can Analytic Hierarchy Process be Used to Elicit Individual Preferences? Insights from a Survey in Patients Suffering from Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Patient 2016, 9, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokala, P.; Devlin, N.; Marsh, K.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kalo, Z.; Longrenn, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for Health Care Decision Making—An Introduction: Report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsh, K.; IJzerman, M.; Thokala, P.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kaló, Z.; Lönngren, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for Health Care Decision Making—Emerging Good Practices: Report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abiiro, G.A.; Leppert, G.; Mbera, G.B.; Robyn, P.J.; De Allegri, M. Developing attributes and attribute-levels for a discrete choice experiment on micro health insurance in rural Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollin, I.L.; Craig, B.M.; Coast, J.; Beusterien, K.; Vass, C.; DiSantostefano, R.; Peay, H. Reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference study protocols and corresponding survey instruments: Guidelines for authors and reviewers. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2020, 13, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coast, J.; Al-Janabi, H.; Sutton, E.J.; Horrocks, S.A.; Vosper, A.J.; Swancutt, D.R.; Flynn, T.N. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: Issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases e.V. (DZNE). PreDemCare: Moving towards Person-Centered Care of People with Dementia—Elicitation of Patient and Physician Preferences for Care. Available online: https://www.dzne.de/en/research/studies/projects/predemcare/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rädke, A.; Mohr, W.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. POSA422 Preferences for Person-Centred Care Among People with Dementia in Comparison to Physician’s Judgments: Study Protocol for the Predemcare Study. Value Health 2022, 25, S272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, W.; Rädke, A.; Afi, A.; Edvardsson, D.; Mühlichen, F.; Platen, M.; Roes, M.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Key Intervention Categories to Provide Person-Centered Dementia Care: A Systematic Review of Person-Centered Interventions. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2021, 84, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision-making with the AHP: Why is the principal eigenvector necessary. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 145, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, L. Methoden der Präferenzmessung: Grundlagen, Konzepte und Experimentelle Untersuchungen; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, T.; Thyrian, J.R.; Dreier, A.; Wucherer, D.; Köhler, L.; Fiß, T.; Böwing, G.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Dementia care management: Going new ways in ambulant dementia care within a GP-based randomized controlled intervention trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. Making good decisions in healthcare with multi-criteria decision analysis: The use, current research and future development of MCDA. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2016, 14, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruoglu, E.; Guldal, D.; Mevsim, V.; Gunvar, T. Which family physician should I choose? The analytic hierarchy process approach for ranking of criteria in the selection of a family physician. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, M.; Mabry, L. RealWorld Evaluation: Working under Budget, Time, Data, and Political Constraints; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, K.; Lafortune, L.; Kavanagh, J.; Thomas, J.; Mays, N.; Erens, B. Non-Drug Treatments for Symptoms in Dementia: An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Non-Pharmacological Interventions in the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Challenging Behaviours in Patients with Dementia; The Policy Research Unit in Policy Innovation Research (PIRU): London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, P.; Hughes, J.; Xie, C.; Larbey, M.; Roe, B.; Giebel, C.M.; Jolley, D.; Challis, D.; Group, H.D.P.M. Overview of systematic reviews: Effective home support in dementia care, components and impacts—Stage 1, psychosocial interventions for dementia. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2845–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, H.; Clarkson, P.; Davies, L.; Sutcliffe, C.; Davies, S.; Feast, A.; Hughes, J.; Challis, D.; Members of the HOST-D (Home Support in Dementia) Programme Management Group. People with dementia and carer preferences for home support services in early-stage dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Orrell, M.; Williams, G.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Romeo, R.; Woods, B.; Garrod, L.; Testad, I.; Woodward-Carlton, B. Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P.; van Weert, J.C.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; van Meijel, B.; Dröes, R.-M. Testing the implementation of the Veder Contact Method: A theatre-based communication method in dementia care. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Thein, K.; Marx, M.S.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Freedman, L. Efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions for agitation in advanced dementia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, J.; Ballard, C.; Juszczak, E.; James, I.; Alder, N.; Jacoby, R.; Howard, R. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawton, M.P.; Van Haitsma, K.; Klapper, J.; Kleban, M.H.; Katz, I.R.; Corn, J. A stimulation-retreat special care unit for elders with dementing illness. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1998, 10, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, F.H.E.; Thompson, C.L.; Nieh, C.M.; Nieh, C.C.; Koh, H.M.; Tan, J.J.C.; Yap, P.L.K. Person-centered care for older people with dementia in the acute hospital. Alzheimer Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, E.S.; Eppingstall, B.; Camp, C.J.; Runci, S.J.; Taffe, J.; O’Connor, D.W. A randomized crossover trial to study the effect of personalized, one-to-one interaction using Montessori-based activities on agitation, affect, and engagement in nursing home residents with Dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haitsma, K.S.; Curyto, K.; Abbott, K.M.; Towsley, G.L.; Spector, A.; Kleban, M. A randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; van Rossum, E.; Ambergen, T.; Kempen, G.I.; Hamers, J.P. Effects of small-scale, home-like facilities in dementia care on residents’ behavior, and use of physical restraints and psychotropic drugs: A quasi-experimental study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weert, J.C.; van Dulmen, A.M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.M.; Ribbe, M.W.; Bensing, J.M. Effects of snoezelen, integrated in 24 h dementia care, on nurse–patient communication during morning care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 58, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sloane, P.D.; Hoeffer, B.; Mitchell, C.M.; McKenzie, D.A.; Barrick, A.L.; Rader, J.; Stewart, B.J.; Talerico, K.A.; Rasin, J.H.; Zink, R.C. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; King, M.T.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Brodaty, H.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Norman, R.; Haas, M.; Luscombe, G. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritz, H.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Williams, J.; Kroeker, K.; Martin, R.R.; Lix, L.M.; Hunter, P.V. A life history intervention for individuals with dementia: A randomised controlled trial examining nursing staff empathy, perceived patient personhood and aggressive behaviours. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokstad, A.M.M.; Røsvik, J.; Kirkevold, Ø.; Selbaek, G.; Benth, J.S.; Engedal, K. The effect of person-centred dementia care to prevent agitation and other neuropsychiatric symptoms and enhance quality of life in nursing home patients: A 10-month randomized controlled trial. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2013, 36, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testad, I.; Mekki, T.E.; Førland, O.; Øye, C.; Tveit, E.M.; Jacobsen, F.; Kirkevold, Ø. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)—training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Tolson, D.; Eerlingen, R.; Carvers, D.; Wouters, K.; Paque, K.; Timmermans, O.; Dilles, T.; Engelborghs, S. SolCos model-based individual reminiscence for older adults with mild to moderate dementia in nursing homes: A randomized controlled intervention study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 23, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; Forbes, I.; Fleming, R.; King, M.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Luscombe, G.; Kenny, P.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Haas, M.; Brodaty, H. PerCEN: A cluster randomized controlled trial of person-centered residential care and environment for people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, G.; Draskovic, I.; Adang, E.M.; Donders, R.; Zuidema, S.U.; Koopmans, R.T.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J. Effects of dementia-care mapping on residents and staff of care homes: A pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villar, F.; Celdrán, M.; Vila-Miravent, J.; Fernández, E. Involving institutionalized people with dementia in their care-planning meetings: Impact on their quality of life measured by a proxy method: Innovative Practice. Dementia 2019, 18, 1936–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.F.; Sculpher, M.J.; Claxton, K.; Stoddart, G.L.; Torrance, G.W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Rudolph, I.; Lincke, H.-J.; Nübling, M. Preferences for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Bethge, S. Patients’ preferences: A discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2015, 16, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A.; Dippel, F.-W.; Bethge, S. Patient priorities for treatment attributes in adjunctive drug therapy of severe hypercholesterolemia in germany: An analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2018, 34, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbacher, A.; Bethge, S.; Kaczynski, A.; Juhnke, C. Objective criteria in the medicinal therapy for type II diabetes: An analysis of the patients’ perspective with analytic hierarchy process and best-worst scaling. Gesundh. (Bundesverb. Der Arzte Des. Offentlichen Gesundh.) 2015, 78, 326. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A. The expert perspective in treatment of functional gastrointestinal conditions: A multi-criteria decision analysis using AHP and BWS. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2016, 23, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weernink, M.G.; van Til, J.A.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.; IJzerman, M.J. Patient and public preferences for treatment attributes in Parkinson’s disease. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2017, 10, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danner, M.; Vennedey, V.; Hiligsmann, M.; Fauser, S.; Stock, S. Focus Groups in Elderly Ophthalmologic Patients: Setting the Stage for Quantitative Preference Elicitation. Patient 2016, 9, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaudig, M.; Mittelhammer, J.; Hiller, W.; Pauls, A.; Thora, C.; Morinigo, A.; Mombour, W. SIDAM—A structured interview for the diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer type, multi-infarct dementia and dementias of other aetiology according to ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Psychol. Med. 1991, 21, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 23 February 2014).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/%20fqs/article/view/1089/2385 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P.; McCabe, R. Subjective experiences of cognitive decline and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: Qualitative interviews with people recently diagnosed in memory clinics in the UK. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacsu, J.R.; O’Connell, M.E.; Webster, C.; Poole, L.; Wighton, M.B.; Sivananthan, S. A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W.; Bohlken, J.; Kostev, K. Effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on disease recognition and utilisation of healthcare services in the older population in Germany: A cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 2020, 50, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haitsma, K.; Abbott, K.M.; Arbogast, A.; Bangerter, L.R.; Heid, A.R.; Behrens, L.L.; Madrigal, C. A Preference-Based Model of Care: An Integrative Theoretical Model of the Role of Preferences in Person-Centered Care. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Til, J.A.; Ijzerman, M.J. Why Should Regulators Consider Using Patient Preferences in Benefit-risk Assessment? PharmacoEconomics 2014, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edvardsson, D.; Varrailhon, P.; Edvardsson, K. Promoting person-centeredness in long-term care: An exploratory study. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fazio, S.; Pace, D.; Flinner, J.; Kallmyer, B. The Fundamentals of Person-Centered Care for Individuals With Dementia. Gerontologist 2018, 58, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jayadevappa, R.; Chhatre, S.; Gallo, J.J.; Wittink, M.; Morales, K.H.; Lee, D.I.; Guzzo, T.J.; Vapiwala, N.; Wong, Y.-N.; Newman, D.K. Patient-centered preference assessment to improve satisfaction with care among patients with localized prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, J.F.P.; Hauber, A.B.; Marshall, D.; Lloyd, A.; Prosser, L.A.; Regier, D.A.; Johnson, F.R.; Mauskopf, J. Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—a Checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011, 14, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kløjgaard, M.E.; Bech, M.; Søgaard, R. Designing a stated choice experiment: The value of a qualitative process. J. Choice Model. 2012, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hannemann, N.; Götz, N.-A.; Schmidt, L.; Hübner, U.; Babitsch, B. Patient connectivity with healthcare professionals and health insurer using digital health technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A German cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyrian, J.R.; Fiß, T.; Dreier, A.; Böwing, G.; Angelow, A.; Lueke, S.; Teipel, S.; Fleßa, S.; Grabe, H.J.; Freyberger, H.J. Life-and person-centred help in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany (DelpHi): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, L.M. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beuscher, L.; Grando, V.T. Challenges in conducting qualitative research with individuals with dementia. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neidhardt, K.; Wasmuth, T. Die Gewichtung Multipler Patientenrelevanter Endpunkte—Ein Methodischer Vergleich von Conjoint Analyse und Analytic Hierarchy Process unter Berücksichtigung des Effizienzgrenzenkonzepts des IQWIG; Diskussionspapier 02-12; Rechts- und Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät, Universität Bayreuth: Bayreuth, Germany, 2012; ISSN 1611-3837. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function (Descriptions Oriented in [44,45]) | Oriented in named intervention categories by Dickson et al. [44] & Clarkson et al. [45], as well as attributes and levels defined in a previous Discrete Choice Experiment by Chester et al. [46] | |

|---|---|---|

| Potential criteria (oriented in intervention categories to provide Person-Centered Dementia Care as identified in Mohr et al. [36]) | Plausible sub-criteria (oriented in provider, format, setting and/or intensity as identified in Mohr et al. [36]) | |

| To provide access to different forms of social contact to counterbalance the limited contact with others that may be characteristic of the experience of dementia. This social contact may be real or simulated [45]. Examples of activities [47,48,49,50,51,52]: Social simulation tool (e.g., robotic animal, lifelike baby doll, baby video, respite video, stuffed animal, family pictures and family video, writing letters), one-on-one interaction (incl. active listening and communication), conversation (e.g., general and based on newspaper stories, pictures, etc.), group activity | (1) Possibilities for social activities |

|

| To provide structured activities and/or exercise to provide meaningful and engaging experiences that can be a useful counterbalance to difficult behaviors [45]. Examples of activities [47,49,52,53,54]: outdoor walks, gardening. | (2) Possibilities for physical activities |

|

| To provide enhancement and stimulation of cognitive functions through guided practice on a set of standard tasks, reflecting memory, attention or problem solving [45]. Examples of activities [47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55]: puzzles and games, reading, poetry, theatre, arts and crafts, work-like activities, housekeeping tasks, videos and television, sorting. | (3) Cognitive training |

|

| To increase or relax the overall level of sensory stimulation in the environment to counterbalance the negative impact of sensory deprivation/stimulation common in dementia [45]. Examples of activities [47,48,49,51,52,53,54,56]: music (e.g., listening, singing along, including in conversations and care), sensory stimulation with different materials, e.g., hand massage with lotion, smelling fresh flowers, preferably in a white and quiet room (refers to Snoezelen). | (4) Activities for sensory stimulation or relaxation |

|

| To assist with basic care, e.g., provision of laundry services, basic nutrition and help with activities of daily living [45]. Examples of activities [47,49,54,55,57]: care (e.g., help with personal hygiene and dressing, discussions about health status with physician), food or drinks, person-centered showering/towel bath. | (5) Help with activities of daily living |

|

| To address feelings and emotional needs through prompts, discussion or by stimulating memories and enabling the person to share their experiences and life stories; undertaken to counterbalance and help people manage difficult feelings and emotions [45]. Examples of activities [47,48,50,54,58,59,60,61,62]: telling life histories, work with reminiscence and self-validation. | (6) Attention and support with worries, feelings and memories |

|

| To change interactions between CGs and PlwD, including: psycho-education; integrated family support, such as counseling and advocacy; training in awareness and problem solving; and support groups [44]. Examples of activities [47,48,50,51,52,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]: training, further education and counseling of professional caregivers (e.g., about dementia-related medication), work experience | (7) Dementia- and PCC specialized training for professional CGs a |

|

| Provision and access of information about dementia, as well as PCC for informal CGs. Emotional support of informal CGs. Inclusion of the family in care decisions. Examples of activities [47,48,50,51,52,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]: access to informational material via GP, Dementia support groups or the internet, self-help groups for informal caregivers, inclusion in care decisions by professional CG and/or GP. | (8) Dementia focused information and support for family CGs a |

|

| To modify the living environment, including the visual environment, in order to lessen agitation and/or to wander and promote safety [45]. Examples of activities [47,50,55,63]: Physical aids, homey adaptions to environment, assistive technology, sign-age, reduction of noise and clutter. | (9) Adjustments of the environment |

|

| To connect and bring together different services around the person; to advise on and negotiate the delivery of services from multiple providers on behalf of the person to provide benefit [45]. Examples of activities [47,50,51,52,55,58,60,61,63,64,65]: shared decision- making between professional CG and/or GP and PlwD, interdisciplinary and integrated care planning incl. consistent staffing, case management, special dementia units in hospitals. | (10) Organization of care |

|

| Possible additional out-of-pocket payments. | (11) Additional cost b |

|

| Possible additional waiting time, which would have to be taken into account for certain offers. | (12) Waiting time b |

|

| Characteristic | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 60–71 | 2 | |

| 71–80 | 2 | |

| 81–90 | 4 | |

| >90 | 2 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 4 | |

| Male | 6 | |

| Family status | ||

| Married | 5 | |

| Widowed | 3 | |

| Divorced or separated | 2 | |

| Highest educational degree | ||

| No degree | 1 | |

| 8th/9th grade | 4 | |

| 10th grade | 2 | |

| Degree from a technical/vocational college | 1 | |

| Degree from a university of applied sciences or university | 2 | |

| Monthly net income | ||

| 500–1000 € | 2 | |

| 1001–1500 € | 2 | |

| 1501–2000 € | 1 | |

| Prefer not to say | 5 | |

| Time since diagnosis of dementia a | ||

| 1–2 years | 3 | |

| 2–5 years | 3 | |

| More than 5 years | 3 | |

| Not known | 1 | |

| Stage of cognitive impairment b | ||

| Early | 8 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Subjective assessment of current health status | ||

| Good | 4 | |

| Satisfactory | 5 | |

| Less good | 1 | |

| Criterion | Examples a | Key Quotations from Qualitative Data (Individual Interviews with n = 10 PlwD and n = 3 Informal CGs) | Plausible Sub-Criteria | Final Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social relationships | Conversations, writing letters, phone calls, meeting friends, club room in facility of community housing, attention and support with worries and feelings | P: So. That you are in touch with other people. That you don’t say no to the connection to other people, but that you look for it [the connection]. (Int9, lls. 14–15) I1: Do you prefer direct contact with people? P: Yes yes. I1: Ok. How about a phone call? P: Well I can make a phone call, but I mostly avoid it. I1: Because you prefer direct contact? P: Yes. (Int9, lls. 24–29) |

| Yes |

| Cognitive training | Listening to the radio, crossword puzzles, puzzles and games, reading the newspaper, reading books, theater, arts and crafts, work-related tasks, watching TV, cleaning. | P: News. All the news I can get. Or comments. So the radio is important to me. I’ve already bought a portable radio like this. So I was looking for the smallest and that was the smallest. Smaller was not possible. And that’s important to me. (Int7, lls. 155–157) P: Yeah…I do that…well play… we used to play Skat [German card-game] too. […] But now…because of Corona…we always played Skat on Sundays and then it was also the afternoon of games… we had an afternoon where we sat and talked at a long table… (Int2, lls. 93–97) |

| Yes |

| Organization of health care | See sub-criteria. | I1: […] Polyclinics. You surely know them from the GDR, where everything was under one roof. [...] P: Hmm, we still have that in the medical center. I1: Hm, do you think that’s good? P: I think that’s good. That is still like before. [...] I1: And would it be important to you that it stays that way, because it’s a good concept or would you say that it works even if the doctors are distributed? P: Nah no…I don’t think that’s good at all. I got all of them close by, the doctors, so I don’t have to drive far. (Int10, lls. 602–603, 608–610, 630–633) P: Well, not that they said “go to the clinic”—I was asked... I1: Exactly and you think that’s good? P: Yes. I think that is good. (Int10, lls. 648–650) |

| Yes |

| Assistance with daily activities | Grocery shopping, cleaning, getting dressed, showering, eating and drinking | P: Well it has to! There is a bit of a must behind it… I don’t know what would be without them [mobile nursing service]. (Int8, lls. 226–227) P: So the help from my wife is very important. (Int9, lls. 256) CG: Nope. No nursing service. They came before […], but they didn’t always come [at times we preferred] and then I said I’ll learn it and do it myself. […] because we are less bound to them like this, otherwise you are always bound to them. Because they don’t come when they want, but when they have time. (Int1, lls. 117–119, 160–161) |

| Yes |

| Characteristics of professional CG | See sub-criteria. | P: […] The important thing is that you can deal with people, you are nice and friendly, you do the work that needs to be done. But I don’t need to study for that […] I think that’s nonsense. [...] (Int10, lls. 474–476, 493–494) P: Well I mean sure. I mean that they know what they are doing in their job, right? I1: Okay…so that’s important to you, the training and professional experience [of the nursing staff]? P: Well, I don’t have an overview of what they have to learn and don’t have to learn, but I mean if a nurse comes here [...] when I need help, I assume she knows how to help me. I1: And that is why training is important to you? P: Yes, that’s how I think about it. At the moment I don’t need it, but it can happen that I need it and then… (Int2, lls. 203–210) |

| Yes |

| Physical activities | Walks, gardening, sports, fishing, cleaning | P: [Physical activity] I do for myself… (Int5, lls. 110) CG: Yes. Aren’t you doing group sports with your hands? I2: Exercise? P: Ooooooh yes! Then we sit there like that [hands up] and off we go. With the feet too! (Int1, lls. 79–81) I1: [...] the physical activity…so you said walking and gardening…but if you compare it to the social [activities], would it be important to you for your care that you have that [physical activities], or is it just the way it is? P: Yes, so that is important…that I can get out! (Int7, lls. 127–130) |

| Yes |

| Dementia focused information and support for family CGs | Access to informational material via GP, Dementia support groups or the internet, self-help groups for informal CGs, inclusion in care decisions by professional CG and/or GP. | I1: Is it important to you that your children […] are informed about your condition? P: Yes, my boy comes with me to the heart specialist…[…] with Dr. XXX… I always let them [children] come with me. I always say four ears hear more than two. (Int10, lls. 543–546) |

| Merged |

| Adjustments of the environment | Physical aids, homey adaptions of environment, assistive technology, sign-age, reduction of noise and clutter. | P: Oh so for the apartment now [adjustments]? I1: Exactly. P: This is all fine here. I1: Have you preinstalled this here, for example handles in the shower to hold on to? P: Yes, everything preinstalled I1: Do you think that’s good? P: I think that’s good. But I don’t need it. (Int7, lls. 420–427) |

| No |

| Activities for sensory stimulation or relaxation | Music (e.g., listening, singing along, including in conversations and care), sensory stimulation with different materials, e.g., hand massage with lotion, smelling fresh flowers, preferably in a white and quiet room (refers to Snoezelen). | I1: Do you like to touch this? Does that feel good? P: Well… I1: Or is that just part of life? P: Well…I haven’t given it that much thought yet… (Int9, lls. 176–179) I2: I’ll put it this way, it is just part of life. P: Yes, exactly…I mean when you’ve got some flowers…[…] of course you smell them. But is that so [something important]? (Int2, lls. 147–149) |

| No |

| Attention and support with worries, feelings and memories | Telling life histories, work with reminiscence and self-validation. | P: […] I don’t need that… I1: Don’t you have any worries? P: No, what should I worry about? [Shrugs shoulders] (Int8, lls. 232–234) P: No, here [day clinic] … I don’t have anyone I want to talk to about the problems. I’d rather be with a friend or something…but this, as I said, is intimate for me. I1: So with family, friends…? P: Hm. (Int5, lls. 254–259) |

| Merged |

| Waiting time | Possible additional waiting time, which would have to be taken into account for certain offers. | P: Well, I mean…as a pensioner you have time and if you sit and wait for a quarter of an hour, that doesn’t matter. (Int8, lls. 495–496) P: […] People shouldn’t always complain right away anyway […] I don’t know any waiting time or almost not. I1: Ok. So you have had very good experiences? P: […] I mean […] I know how it works in a clinic. And I have no problem with that. I1: That means it doesn’t matter to you whether you wait a week or 14 days for an appointment. P: No. I1: And when you are at the doctor, you don’t care… P: It’s just the way it is. (Int5, lls. 405–414) |

| No |

| Additional cost | Possible additional out-of-pocket payments. | P: Important? It is there. That’s the way it is and if I want something, then I pay for it. (Int4, lls. 427) I1 […] Is this an issue for you or… P: No, not at all. I1: …is that how it is? P: I have a good pension and I can get by with it. [...] these are co-payments. There is nothing more to it. (Int7, lls. 483–486, 496) |

| No |

| Category # | Key Quotations from Qualitative Data (Individual Interviews with n = 10 PlwD (and n = 3 Informal CGs)) |

|---|---|

| (2) New patient relevant criteria of PCC | I1: Is there anything, which was not included in the cards, but which you think we should write down? Because we also have blank cards and can create new criteria […] Is there anything we forgot? P: No. I1: It is well illustrated? P: It is well illustrated. (Int3, lls. 289–295) |

| (4) Overlapping of criteria | P: We find someone in the house to talk to. Sometimes, we sat outside on the bench. But that I [talk with other’s about my worries] well. Here with them [other residents in the apartment building]...I am the one who says “no, do this, do that”. [...] I1: Do you think that this [Criterion 6,Table 1] overlaps a bit or is the same as the social activities? Because you there [Criterion 1,Table 1] you also talk? P: Possible. (Int8, lls. 238–245) |

| (5) Wording and comprehensibility | P: Social aspects [Criterion 1,Table 1] means… [reads] that this will be and the other is in the future. I1: You don’t have to make it that complicated. P: No? I1: What is that for you? Do you have friends? Do you have a dog? P: I would have only thought about the medical side of this now. [...]. (Int5, lls. 13–17) |

| (6) Observations during interviews | |

| (a) Reactions by patient | P: Let’s say the...how should you say this... what happens but...no...so...[participant is nervous] eh could you ask your question again briefly? (Int5, lls 29–30) I2: Um, this [criterion 8,Table 1] is about information and support if you have family members. […] you said you do everything by yourself, right? Hence, this might be a bit difficult to answer that [about criterion 8,Table 1] P: Family members…dementia. Yes, the dementia patients need us, they cannot be without us. (Int6, lls 201–204) P: And that they know [what to do], the nursing specialists [cf. criterion 7,Table 1] that is very clearly [important]. [...]. (Int2, lls. 432) |

| (b) Interaction with informal CG | P: What are you doing now? [towards informal CG] CG: No! That we both can [do something]. That you are with me is of no use to you either, you have to be with people who are just as sick as you! P: Yes yes, hm. CG: They talk to each other very differently… P: Well if you want to deport me… (Int1, lls. 309–314) P: Yes, I need a change. I need it...very often...anyways, my wife is an impediment with regard to this question because she is afraid that I will somehow tip over or something. But personally... CG: Well, I’m always afraid that he will fall there, because it is not flat in the garden. And he fell there a few times. And then I’m afraid that he will fall again. And that’s why I only let him do things where the danger of falling is not likely. Where he doesn’t have to bend down, where he can stand up straight. (Int9, lls. 207–212) I1: Ok. Great. You’re doing really well. That helps us a lot. So activities of daily living. It’s like eating, showering, everything you do every day. Getting dressed...I think you are still very physically fit. You can still do it all [by yourself]. P: Yeah. I1: Do you currently need help with [anything] or do you do everything on your own? P: I do a lot of things on my own. I don’t want to say everything, but a lot. I2: Most of it, yes? P: Yes. I1: If you should ever need help, would it be important for you to get help? P: Yeah. Well. I have a wife who knows everything. She also studied. (Int4, lls. 235–244) |

| (c) Explorative vs. card game | I1: We thought that [social] activities for example could be individual or group discussions, writing letters, videos, working with figures. But you cannot relate anything to that? P: No. Why should we waste our time with this? (Int1, lls. 25–27) I1: Okay. So you would say that this [criterion 10,Table 1] is maybe of middle importance? P: Yeah well...not at the moment, as long as I can still do it by myself. But if I then...so if I were to forget that...then...[…] We chose Dr. [XXX]. We didn’t know her...but she was nearby. So we didn’t have to walk far. Or take the bus or something. I1: Okay. So. Proximity is important...it’s kind of important. [...]. (Int2, lls. 303–310) I1: How would that be, should you ever need that [adjustments of the environment]? Would you like to have that then? P: I think I can take my time. Doesn’t have to be now... from now on I’m sick and now I have to [get help]… (Int5, lls. 347–349) |

| (d) Context | I1: Exactly. [laughs] And there used to be polyclinics in the GDR. P: Yes. I1: How do you like that, the concept? P: Very good! In general I find everything related to GDR very good. (Int4, lls. 391–394) |

| (e) COVID-19 | P: Well, what can I think of [ad criterion 1,Table 1]—well now, due to Corona, drinking coffee has been cancelled. Otherwise, we always had 1–2 h of drinking coffee together [in the community housing clubroom] on Wednesdays and Thursdays in the afternoons. (Int2, lls. 15–16) I1: And do you think it’s good that you can do something like that…go for a walk and something? P: Yeah well, I have to like it. I can no longer travel, I imagined my retirement to be different. But everything is gone and now the disease [is there] too. The big one. I1: You mean Corona? P: Corona, that’s exactly what I mean. I always forget the name. (Int7, lls. 101–105) P: Yes, but this is no longer…otherwise you would have had more contact [sad]. I1: Hm. Because of Corona it is no longer [the contact]? P: Yes. CG: Yes, unfortunately it is...really bad with Corona. (Int9, lls. 39–42) CG: We did sports until Corona. We’re still in the sports group, but we’ll cancel our membership because he can’t do it anymore. He can no longer participate, no matter what we did there. It doesn’t work anymore. He has lost so much lately. (Int9, lls. 83–85) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohr, W.; Rädke, A.; Afi, A.; Mühlichen, F.; Platen, M.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Development of a Quantitative Instrument to Elicit Patient Preferences for Person-Centered Dementia Care Stage 1: A Formative Qualitative Study to Identify Patient Relevant Criteria for Experimental Design of an Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137629

Mohr W, Rädke A, Afi A, Mühlichen F, Platen M, Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W. Development of a Quantitative Instrument to Elicit Patient Preferences for Person-Centered Dementia Care Stage 1: A Formative Qualitative Study to Identify Patient Relevant Criteria for Experimental Design of an Analytic Hierarchy Process. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):7629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137629

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohr, Wiebke, Anika Rädke, Adel Afi, Franka Mühlichen, Moritz Platen, Bernhard Michalowsky, and Wolfgang Hoffmann. 2022. "Development of a Quantitative Instrument to Elicit Patient Preferences for Person-Centered Dementia Care Stage 1: A Formative Qualitative Study to Identify Patient Relevant Criteria for Experimental Design of an Analytic Hierarchy Process" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 7629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137629

APA StyleMohr, W., Rädke, A., Afi, A., Mühlichen, F., Platen, M., Michalowsky, B., & Hoffmann, W. (2022). Development of a Quantitative Instrument to Elicit Patient Preferences for Person-Centered Dementia Care Stage 1: A Formative Qualitative Study to Identify Patient Relevant Criteria for Experimental Design of an Analytic Hierarchy Process. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137629