Peer Support and Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Identifying the Research Questions

2.3. Identifying Relevant Information

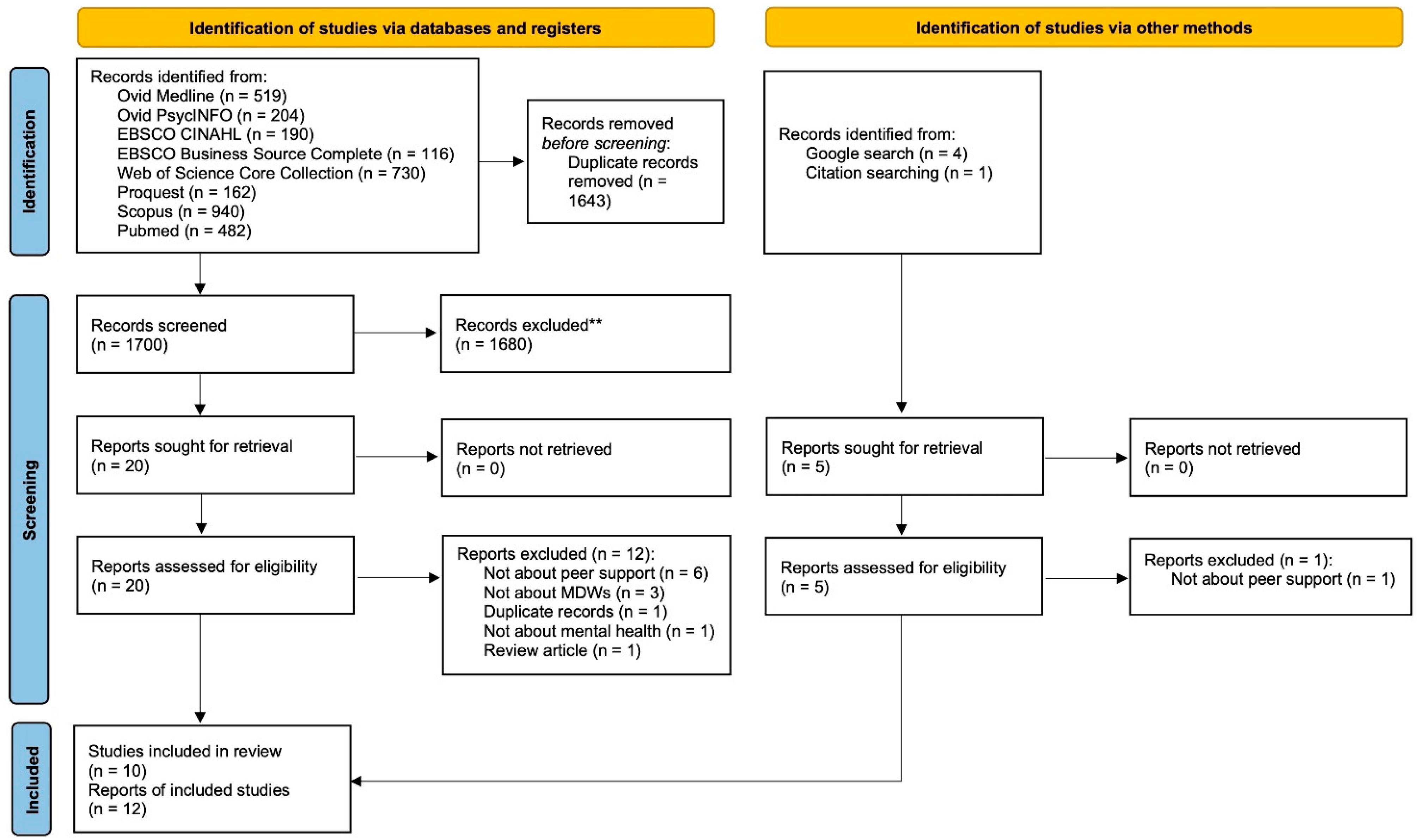

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Charting the Data

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. What Types of Peer Support Are Available to MDWs?

3.2.1. Mutual Aids

3.2.2. Para-Professional Trained Peer Support

3.3. What Are the Functions/Outcomes of Peer Support for MDWs?

3.3.1. Mutual Aids

3.3.2. Para-Professional Trained Peer Support

3.4. What Are the Barriers and Facilitators for MDWs to Provide/Receive Peer Support?

3.4.1. Facilitators

Mutual Aids

Para-Professional Trained Peer Support

3.4.2. Barriers

Mutual Aids

Para-Professional Trained Peer Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basnyat, I.; Chang, L. Examining live-in foreign domestic helpers as a coping resource for family caregivers of people with dementia in Singapore. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anderson, B. Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour; Zed Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Chiang, V.C.L.; Leung, D.; Ku, B.H.B. When foreign domestic helpers care for and about older people in their homes: I am a maid or a friend. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2018, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Cheung, D.S.K.; Lee, P.H.; Lam, S.M.C.; Kwan, R.Y.C. Co-living with migrant domestic workers is associated with a lower level of loneliness among community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. ILO Global Estimates on Migrant Workers: Results and Methodology (Geneva). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_436343.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Gallotti, M. Migrant Domestic Workers across the World: Global and Regional Estimates. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/projects/gap/publications/WCMS_490162/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- ILO. Migrant Domestic Workers: Promoting Occupational Safety and Health. Available online: https://labordoc.ilo.org/discovery/fulldisplay?vid=41ILO_INST:41ILO_V1&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&tab=Everything&docid=alma994906633402676&lang=en&context=L (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Hargreaves, S.; Rustage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; McAlpine, A.; Pocock, N.; Devakumar, D.; Aldridge, R.W.; Abubakar, I.; Kristensen, K.L.; Himmels, J.W.; et al. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e872–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Chiang, V.C.L.; Leung, D.; Cheung, D.S.K. A feminist phenomenology on the emotional labor and morality of live-in migrant care workers caring for older people in the community. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Wilson, I.M.; Wong, J.Y.; McKenna, L.; Reisenhofer, S.; Efendi, F.; Smith, G.D. Health stressors, problems and coping strategies of migrant domestic workers: A scoping review. Res. Sq. 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Domestic Workers across the World: Global and Regional Statistics and the Extent of Legal Protection. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/forthcoming-publications/WCMS_173363/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Holroyd, E.A.; Molassiotis, A.; Taylor-Pilliae, R.E. Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong: Health related behaviors, health locus of control and social support. Women Health 2001, 33, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordeno, I.G.; Carpio, J.G.E.; Mendoza, N.B.; Hall, B.J. The latent structure of major depressive symptoms and its relationship with somatic disorder symptoms among Filipino female domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palupi, K.C.; Shih, C.K.; Chang, J.S. Cooking methods and depressive symptoms are joint risk factors for fatigue among migrant Indonesian women working domestically in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, S61–S67. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, N.C.Y.; Kan, K.K.Y.; Wong, A.L.Y.; Lau, J.T.F. Self-stigma, resilience, perceived quality of social relationships, and psychological distress among Filipina domestic helpers in Hong Kong: A mediation model. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.J.; Pangan, C.A.C.; Chan, E.W.W.; Huang, R.L. The effect of discrimination on depression and anxiety symptoms and the buffering role of social capital among female domestic workers in Macao, China. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjara, S.G.; Nellums, L.B.; Bonetto, C.; Van Bortel, T. Stress, health and quality of life of female migrant domestic workers in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2017, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garabiles, M.R.; Lao, C.K.; Xiong, Y.; Hall, B.J. Exploring comorbidity between anxiety and depression among migrant Filipino domestic workers: A network approach. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 250, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Smith, G.D. A discursive paper on the importance of health literacy among foreign domestic workers during outbreaks of communicable diseases. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4827–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, N.C.Y.; Huang, B.; Lau, C.Y.K.; Lau, J.T.F. Feeling anxious amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychosocial correlates of anxiety symptoms among filipina domestic helpers in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, I.D.; Vandan, N.; Davies, S.E.; Harman, S.; Morgan, R.; Smith, J.; Wenham, C.; Grépin, K.A. “We also deserve help during the pandemic”: The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.M. The impacts of COVID-19 on foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 10, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ham, A.J.; Ujano-Batangan, M.T.; Ignacio, R.; Wolffers, I. Toward healthy migration: An exploratory study on the resilience of migrant domestic workers from the Philippines. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, E.B.; Coufal, M.M.; Parada, H.; Robinette, J.B.; Tang, P.Y.; Urlaub, D.M.; Castillo, C.; Guzman-Corrales, L.M.; Hino, S.; Hunter, J.; et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Plaza, S.; Alonso-Morillejo, E.; Pozo-Muñoz, C. Social support interventions in migrant populations. Br. J. Soc. Work 2006, 36, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L. Peer support within a health care context: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2003, 40, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.T.; Clifton, A.V.; Zhao, S.; Lui, S. Peer support for people with schizophrenia or other serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD010880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bracke, P.; Christiaens, W.; Verhaeghe, M. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and the balance of peer support among persons with chronic mental health problems. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 436–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmitorz, A.; Kunzler, A.; Helmreich, I.; Tüscher, O.; Kalisch, R.; Kubiak, T.; Wessa, M.; Lieb, K. Intervention studies to foster resilience–A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 59, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà-sales, S.; Pérez-gonzález, N.; Van Hoey, J.; Iborra-marmolejo, I.; Beneyto-arrojo, M.J.; Moret-tatay, C. Article the role of resilience for migrants and refugees’ mental health in times of COVID-19. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, P.N.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D.; Rogers, M.A.M.; Valenstein, M. Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: A meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, D.W.L.; Li, J.; Ou, X.; Li, C.Y.P. Effectiveness of a peer-based intervention on loneliness and social isolation of older Chinese immigrants in Canada: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-Reeves, J.; Murray-Krezan, C.; Regino, L.; Perez, J.; Bleecker, M.; Perez, D.; Wagner, B.; Tigert, S.; Bearer, E.L.; Willging, C.E. A randomized control trial to test a peer support group approach for reducing social isolation and depression among female Mexican immigrants. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badali, J.J.; Grande, S.; Kassabian, K. From Passive Recipient to Community Advocate: Reflections on Peer-Based Resettlement Programs for Arabic-Speaking Refugees in Canada. Glob. J. Community Psychol. Pract. 2017, 8, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Im, H.; Rosenberg, R. Building Social Capital Through a Peer-Led Community Health Workshop: A Pilot with the Bhutanese Refugee Community. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paloma, V.; de la Morena, I.; Sladkova, J.; López-Torres, C. A peer support and peer mentoring approach to enhancing resilience and empowerment among refugees settled in southern Spain. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Regional Office for Europe. Mental Health Promotion and Mental Health Care in Refugees and Migrants. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/386563/mental-health-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Mahlke, C.I.; Krämer, U.M.; Becker, T.; Bock, T. Peer support in mental health services. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, N.B.; Mordeno, I.G.; Latkin, C.A.; Hall, B.J. Evidence of the paradoxical effect of social network support: A study among Filipino domestic workers in China. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 255, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, F.N. Better a friend nearby than a brother far away? The Health implications of foreign domestic workers’ family and friendship networks. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, R.; Valmadrid, L.; Panlaqui, E.L.; Pendon, N.L.; Juan, P. Responding to the structural violence of migrant domestic work: Insights from participatory action reserach with migrant caregivcers in Canada. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.J.; Garabiles, M.R.; Latkin, C.A. Work life, relationship, and policy determinants of health and well-being among Filipino domestic workers in China: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, H.J. Coping with trauma in domestic migrant worker narratives: Linguistic, emotional and psychological perspectives. J. Socioling. 2015, 19, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktavianus, J.; Lin, W.Y. Soliciting social support from migrant domestic workers’ connections to storytelling networks during a public health crisis. Health Commun. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, R.B.; Chang, C.W. Formal and informal social support systems for migrant domestic workers. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 784–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.H.M.; Keng, S.L.; Buck, P.J.; Suthendran, S.; Wessels, A.; Østbye, T. Effects of mental health paraprofessional training for Filipina foreign domestic workers in Singapore. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrigglesworth, J.W. Chasing Desires and Meeting Needs: Filipinas in South Korea, Mobile Phones, Social Networks, Social Support and Informal Learning; The Pennsylvania State University: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016; Volume 78. [Google Scholar]

- Suthendran, S.; Wessels, A.; Heng, M.W.M.; Shian-Ling, K. How to Implement Peer-Based Mental Health Services for Foreign Domestic Workers in Singapore? In Proceedings of the Migrating Out of Poverty: From Evidence to Policy Conference, London, UK, 28 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, K.X. Maids Trained to Be Counsellors to Peers. Available online: https://www.nus.edu.sg/newshub/news/2016/2016-04/2016-04-11/MAIDS-st-11apr-pB1-B2.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Fortuna, K.L.; Solomon, P.; Rivera, J. An update of peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr. Q. 2022, 93, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics Home Sweet Home? Work, Life and Well-Being of Foreign Domestic Workers in Singapore. Available online: https://idwfed.org/en/resources/home-sweet-home-work-life-and-well-being-of-foreign-domestic-workers-in-singapore/@@display-file/attachment_1 (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Herrando, C.; Constantinides, E. Emotional contagion: A brief overview and future directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, H.; Schweizer, R.; Marks, E.; Yuan, L.; Lloyd, C.; Ramjan, R. The effectiveness of support groups: A literature review. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2018, 22, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Sono, T. Lessons from peer support among individuals with mental health difficulties: A review of the literature. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2012, 8, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kemp, V.; Henderson, A.R. Challenges faced by mental health peer support workers: Peer support from the peer supporter’s point of view. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2012, 35, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, I.; Werning, A.; Nossek, A.; Vollmann, J.; Juckel, G.; Gather, J. Challenges faced by peer support workers during the integration into hospital-based mental health-care teams: Results from a qualitative interview study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ham, A.J.; Ujano-Batangan, M.T.; Ignacio, R.; Wolffers, I. The dynamics of migration-related stress and coping of female domestic workers from the Philippines: An exploratory study. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| ||

| Concept |

|

|

| Context |

| - |

| Study design |

|

|

| Author, Year, Country | Aim of Study | Study Design | Sample Characteristics | Type of Peer Support | Functions/Outcomes of Peer Support and Mental Health | Facilitators for | Barriers for |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Support | Peer Support | ||||||

| Baig and Chang, 2020 [50] Hong Kong SAR, China | To explore how migrant domestic workers (MDWs) approach different forms of support systems based on their multiple identities of gender, ethnicity, and religion. | Mixed-methods study |

| Mutual aid |

| NA |

|

| Bhuyan et al., 2018 [46] Canada | To explore MDWs’ response to employer abuse and exploitation following changes to Live-in-Caregiver Program in 2014. | Qualitative study |

| Mutual aid |

|

|

|

| Hall et al., 2019 [47] Macao SAR, China | To identify key health issues Filipino MDWs were facing in their post-migration context, and the social determinants of these issues. | Qualitative study |

| Mutual aid | NA | NA |

|

| Ladegaard, 2015 [48] Hong Kong SAR, China | To investigate how the women make sense of their traumatic experiences, and how peer support becomes essential in the narrators’ attempts to rewrite their life stories from victimhood to survival and beyond. | Qualitative study |

| Mutual aid |

| NA |

|

| Mendoza et al., 2017 [44] Macao SAR, China | To determine the role of social network support in buffering the impact of post-migration stress on mental health symptoms among Filipino MDWs. | Quantitative study |

| Mutual aid |

| NA |

|

| Oktavianus and Lin, 2021 [49] Hong Kong SAR, China | To explore how the storytelling networks of MDWs provided social support amid the COVID-19 pandemic. | Qualitative study |

| Mutual aid |

| NA |

|

| van der Ham et al., 2014 [24] Philippines | To provide insight into the resilience of female domestic workers by presenting the results of an exploratory study on resilience in which personal resources and social resources were investigated in relation to perceived stress and well-being. | Mixed-methods study |

| Mutual aid |

|

|

|

| Wong et al., 2020; Suthendran et al., 2017; Hui, 2016 [51,53,54] Singapore | To assess the acceptability and effectiveness of a Cognitive-Behavioral-Therapy-based para-professional training program for Filipina MDWs. | Mixed-methods study |

| Para-professional trained peer support |

|

|

|

| Wrigglesworth, 2016 [52] South Korea |

| Mixed-methods study |

| Mutual aid |

|

|

|

| Ye and Chen, 2020 [45] Hong Kong SAR, China | To explore the potential health buffering effects of MDWs’ personal network. | Quantitative study |

| Mutual aid |

| NA |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, K.H.M.; Yang, C.; Leung, A.K.Y.; Bressington, D.; Chien, W.T.; Cheng, Q.; Cheung, D.S.K. Peer Support and Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137617

Ho KHM, Yang C, Leung AKY, Bressington D, Chien WT, Cheng Q, Cheung DSK. Peer Support and Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):7617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137617

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Ken Hok Man, Chen Yang, Alex Kwun Yat Leung, Daniel Bressington, Wai Tong Chien, Qijin Cheng, and Daphne Sze Ki Cheung. 2022. "Peer Support and Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 7617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137617

APA StyleHo, K. H. M., Yang, C., Leung, A. K. Y., Bressington, D., Chien, W. T., Cheng, Q., & Cheung, D. S. K. (2022). Peer Support and Mental Health of Migrant Domestic Workers: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137617