Voluntary Counseling and Testing, Antiretroviral Therapy Access, and HIV-Related Stigma: Global Progress and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Global HIV Prevention Efforts and Progress Made after Four Decades

2.1. Voluntary Counselling and Testing

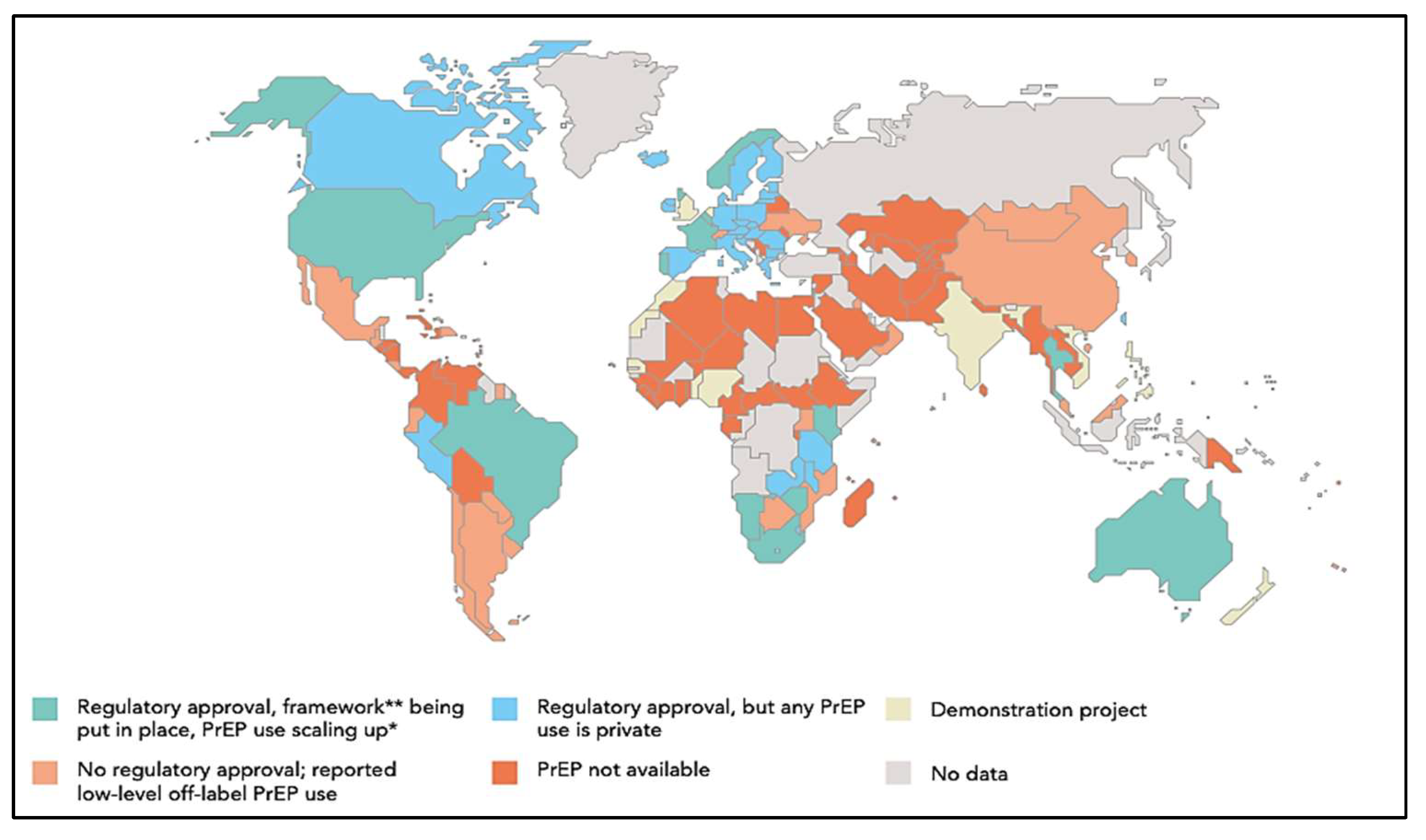

2.2. Antiretroviral Therapy

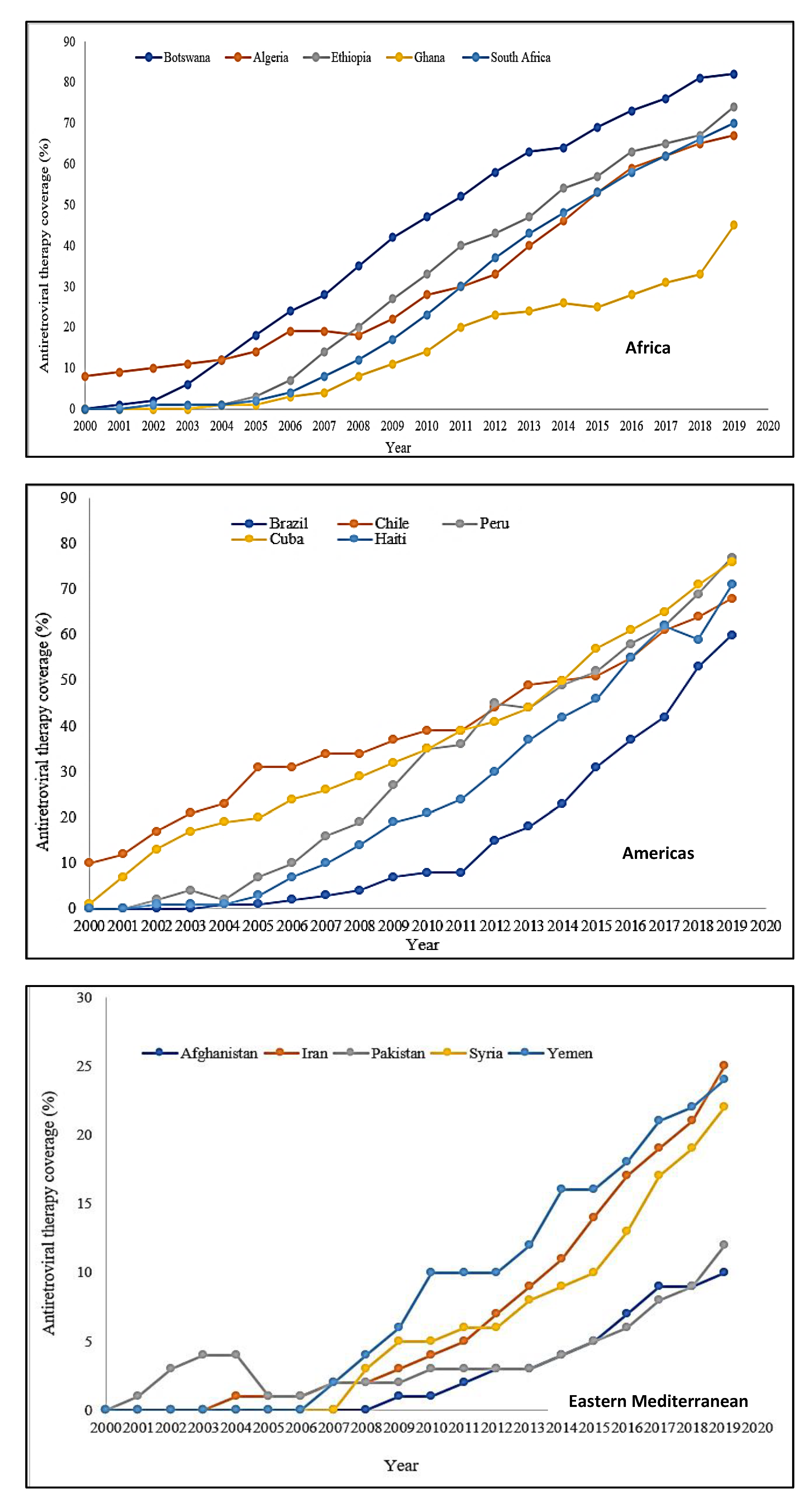

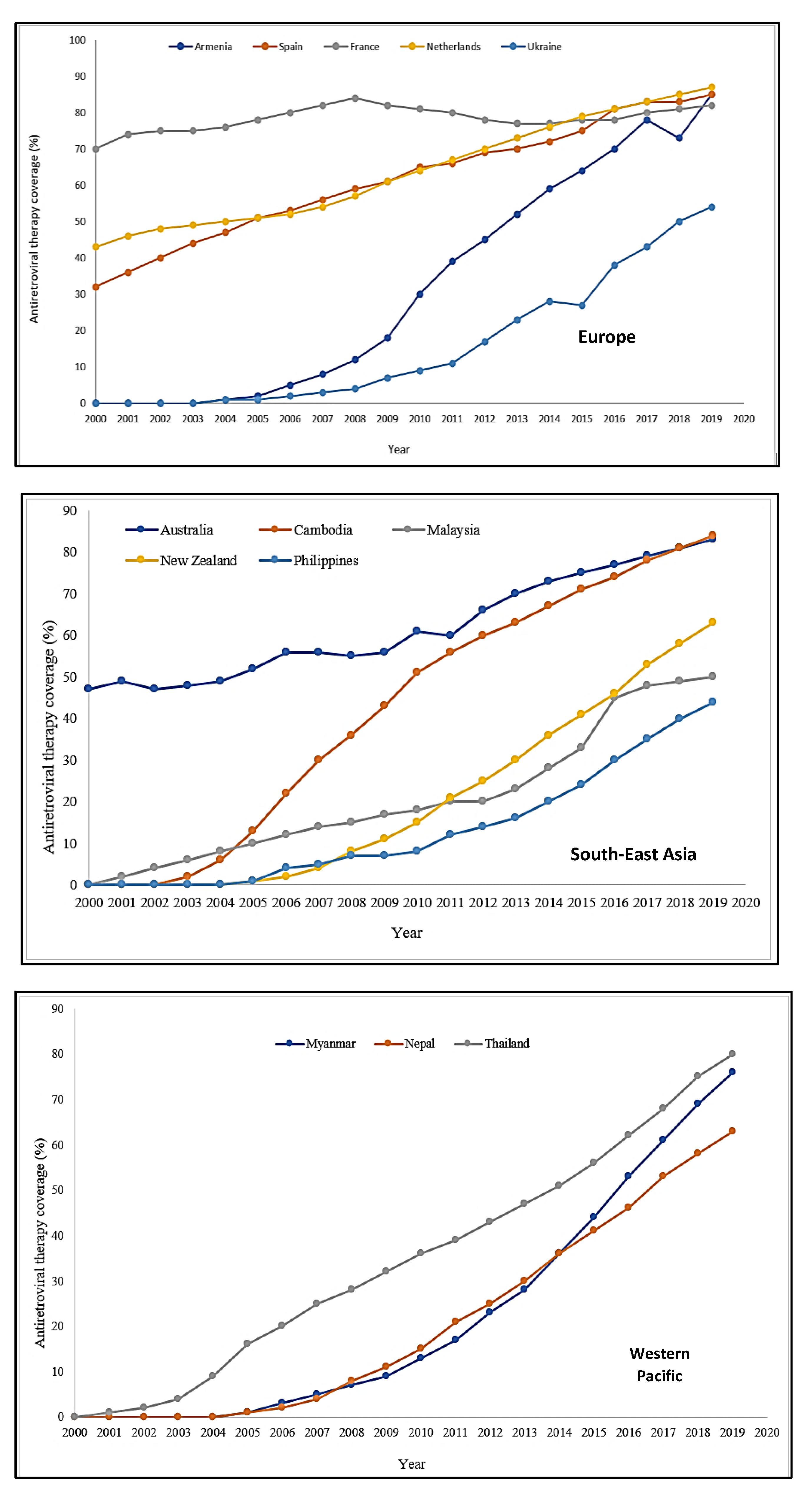

2.2.1. Trends in Antiretroviral Therapy Coverage across WHO Regions

Africa

Americas

Eastern Mediterranean

Europe

Western Pacific

South-East Asia

2.3. HIV-Related Stigma

3. Global HIV Prevention Challenges

3.1. Voluntary Counselling and Testing

3.2. Antiretroviral Therapy

3.3. HIV-Related Stigma

4. The Way Forward

4.1. Funding and Staffing

4.2. Special Populations

4.3. Awareness Creation and Promotion of Benefits

4.4. HIV-Related Stigma

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, A.; Fusheini, A.; Ayanore, M.A.; Amuna, N.; Agbozo, F.; Kugbey, N.; Kubi-Appiah, P.; Asalu, G.A.; Agbemafle, I.; Akpalu, B.; et al. HIV Stigma and Status Disclosure in Three Municipalities in Ghana. Ann. Glob. Health 2021, 87, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Fact Sheet 2021: Global HIV Statistics. Available online: https://embargo.unaids.org/static/files/uploaded_files/UNAIDS_2021_FactSheet_en_em.pdf#:~:text=FACT%20SHEET%202021%20Preliminary%20UNAIDS%202021%20epidemiological%20estimates,people%20became%20newly%20infected%20with%20HIV%20in%202020 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- MDG MONITOR Millennium Development Goals—MDGs. Available online: https://www.mdgmonitor.org/millennium-development-goals/ (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals: Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Grossman, C.I.; Stangl, A.L. Global Action to Reduce HIV Stigma and Discrimination. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. HIV Testing and Counseling: The Gateway to Treatment, Care, and Support. Available online: https://www.who.int/3by5/publications/briefs/hiv_testing_counselling/en/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Hutchinson, P.L.; Mahlalela, X. Utilization of Voluntary Counseling and Testing Services in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS Care 2006, 18, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Agency for International Development. P. S. Voluntary Counseling and Testing Rigorous Evidence—Usable Results. Available online: https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/research-to-prevention/publications/VCT.pdf#:~:text=Voluntary%20Counseling%20and%20Testing%20%28VCT%29%20allows%20individuals%20to,pre-%20and%20post-test%20counseling%20and%20an%20HIV%20test (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Onoja, A.J.; Onoja, S.I.; Sanni, F.O.; Adamu, I.; Abiodun, O.P.; Shaibu, J. Uptake of HIV Testing: Assessing the Impact of a Community-Based Intervention in Rural Nigeria. Health Sci. Dis. 2020, 21, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Karau, P.B.; Winnie, M.S.; Geoffrey, M.; Mwenda, M. Responsiveness to HIV Education and VCT Services Among Kenyan Rural Women: A Community-Based Survey. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2010, 14, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bediru, A. Exploring the Inter Play Between VCT Service Delivery and it’s Amongst Primary School Teachers in South-West Ethiopia. Softw. Eng. Technol. 2019, 11, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Couples HIV Testing and Counselling Including Antiretroviral Therapy for Treatment and Prevention in Serodiscordant Couples: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44646/1/9789241501972_eng.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing Together. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/diagnose/testing-together/index.html (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Doherty, I.A.; Myers, B.; Zule, W.A.; Minnis, A.M.; Kline, T.L.; Parry, C.D.; El-Bassel, N.; Wechsberg, W.M. Seek, Test and Disclose: Knowledge of HIV Testing and Serostatus Among High-risk Couples in a South African Township. Sex. Transm Infect. 2016, 92, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, C.R.; Kirungi, W.; Kaharuza, F.; Buyze, J.; Bunnell, R. Who Knows Their Partner’s HIV Status? Results From a Nationally Representative Survey in Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 69, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Meinzen-Derr, J.; Kautzman, M.; Zulu, I.; Trask, S.; Fideli, U.; Musonda, R.; Kasolo, F.; Gao, F.; Haworth, A. Sexual Behavior of HIV Discordant Couples After HIV Counseling and Testing. AIDS 2003, 17, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, K.M.; Kilembe, W.; Vwalika, B.; Haddad, L.B.; Lakhi, S.; Onuwubiko, U.; Khu, N.H.; Brill, I.; Chavuma, R.; Vwalika, C.; et al. Sustained Effect of Couples’ HIV Counselling and Testing on Risk Reduction Among Zambian HIV Serodiscordant Couples. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ma, P.; Chu, M.; Chen, Y.; Miao, J.; Xia, H.; Zhuang, X. Understanding the Role of Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) in HIV Prevention in Nantong, China. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5740654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayah, N.A.; Mondastri Korb, S. Risk Factors Associated with HIV Infection among General Population in Tanah Papua: Secondary Data Analysis of IBBS in Tanah Papua, Indonesia 2013. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Importance of Simple/Rapid Assays In HIV Testing. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 1998, 73, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Baisley, K.; Doyle, A.M.; Changalucha, J.; Maganja, K.; Watson-Jones, D.; Hayes, R.; Ross, D. Uptake of Voluntary Counselling and Testing Among Young People Participating in an HIV Prevention Trial: Comparison of Opt-out and Opt-in Strategies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, L.; Jimoh, A.K.C.; Balogun, O.R. Factors Hindering Acceptance of HIV/AIDS Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) among Youth in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2010, 14, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.; Tran, B.; Nguyen, N.; Phan, T.; Bui, T.; Latkin, C.A. Mobilization for HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing Services in Vietnam: Clients’ Risk Behaviors, Attitudes and Willingness to Pay. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Provider-Initiated HIV Testing and Counselling in Health Facilities. 2007. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43688/9789241595568_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Marks, G.; Crepaz, N.; Janssen, R.S. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006, 20, 1447–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creek, T.L.; Ntumy, R.; Seipone, K.; Smith, M.; Mogodi, M.; Smit, M.; Legwaila, K.; Molokwane, I.; Tebele, G.; Mazhani, L.; et al. Successful introduction of routine opt-out HIV testing in antenatal care in Botswana. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007, 45, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijadunola, K.; Abiona, T.; Balogun, J.; Aderounmu, A. Provider-initiated (Opt-out) HIV testing and counselling in a group of university students in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2011, 16, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, N.; Naidoo, P.; Mathews, C.; Lewin, S.; Lombard, C. The impact of provider-initiated (opt-out) HIV testing and counseling of patients with sexually transmitted infection in Cape Town, South Africa: A controlled trial. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyenze, R.K.; Nawavvu, C.; Namale, A.S.; Mayanja, B.; Bunnell, R.; Abang, B.; Amanyire, G.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Kamya, M.R. Acceptability of routine HIV counselling and testing, and HIV seroprevalence in Ugandan hospitals. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008, 86, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, T.W.; Seipone, K.; de la Hoz Gomez, F.; Anderson, M.G.; Kejelepula, M.; Keapoletswe, K.; Moffat, H.J. Two and a half years of routine HIV testing in Botswana. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007, 44, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel, R.; Kamthunzi, P.; Mwansambo, C.; Phiri, S.; Kazembe, P.N. Effect of provider-initiated testing and counselling and integration of ART services on access to HIV diagnosis and treatment for children in Lilongwe, Malawi: A pre- post comparison. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PEPFAR Solutions Platform. Index and Partner Notificcation Testing Toolkit. 11 April 2018. Available online: https://www.pepfarsolutions.org/resourcesandtools-2/2018/4/11/index-and-partner-notification-testing-toolkit (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Rooyen, H.; Essack, Z.; Rochat, T.; Wight, D.; Knight, L.; Bland, R.; Celum, C. Taking HIV Testing to Families: Designing a Family-Based Intervention to Facilitate HIV Testing, Disclosure, and Intergenerational Communication. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, K.R.; Flick, R.J.; Kim, M.H.; Sabelli, R.A.; Tembo, T.; Phelps, B.R.; Rosenberg, N.E.; Ahmed, S.J. Family Testing: An Index Case Finding Strategy to Close the Gaps in Pediatric HIV Diagnosis. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 15, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, A.K.; George, J.M. Antiretroviral Therapy: Current Drugs. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 28, 371–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.S.; Chen, Y.Q.; McCauley, M.; Gamble, T.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Kumarasamy, N.; Hakim, J.G.; Kumwenda, J.; Grinsztejn, B.; Pilotto, J.H.S.; et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, M.O.; Scarci, K.; Taiwo, B.; Murphy, R.L. Combination Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors for Treatment of HIV Infection. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliero, P.J. Pharmacokinetic Properties Of Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2004, 37, S2–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S. The History of HIV Treatment: Antiretroviral Therapy and More. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/hiv-treatment-history (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- HIV.gov. PEPFAR. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/pepfar-global-aids/pepfar (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- PEPFAR Reports to Congress 2005–2020. Available online: https://www.state.gov/pepfar-reports-to-congress-archive/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Fauci, A.S.; Lane, H.C. Four Decades of HIV/AIDS—Much Accomplished, Much to Do. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Z. iPrEx Clinical Trial Demonstrate 44 Percent Protection Against HIV—Mounting Evidence of the Power of ARVs to Prevent HIV Transmission. Available online: https://www.ipmglobal.org/publications-media/iprex-clinical-trial-demonstrates-44-protection-against-hiv (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- HIV Prevention Trials Network 052. A Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Antiretroviral Therapy Plus HIV Primary Care Versus HIV Primary Care Alone to Prevent the Sexual Transmission of HIV-1 in Serodiscordant Couples. Available online: https://www.hptn.org/research/studies/hptn052 (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- HIV Prevention Trials Network 084. HPTN 084 Study Demonstrate Superiority of CAB LA to Oral TDF/FTC for the Prevention of HIV. Available online: https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/hptn-084-study-demonstrates-superiority-of-cab-la-to-oral-tdfftc-for (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- US Food and Drug Administration. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2021. Available online: https://www.iapac.org/fact-sheet/dapivirine-vaginal-ring/#:~:text=The%20dapivirine%20ring%20marks%20the,to%20reduce%20their%20HIV%20risk (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- International Partnership for Microbicides. South Africa Approves Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for Use by Women. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipmglobal.org/content/south-africa-approves-dapivirine-vaginal-ring-use-women#:~:text=(March%2011%2C%202022)%E2%80%94,to%20reduce%20their%20HIV%20risk (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Avert, 2019. Treatment as Prevention (TASP) for HIV. Available online: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/treatment-as-prevention (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Latest HIV Estimates and Updates on HIV Policies Uptake, July 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/hiv-hq/presentation-international-aids-conference-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=cbd9bbc_4 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Estimate The World Bank Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.HIV.ARTC.ZS?end=2020&start=2000&view=chart (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Stigma and Discrimination. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/index.html (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- People Living with HIV Stigma Index (October 10, 2021). Available online: http://www.stigmaindex.org/news/oct-2015/we-are-change-dealing-self-stigma-and-hivaids-experience-zimbabwe (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Ngangue, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Bedard, E. Challenges in the Delivery of Public HIV Testing and Counselling (HTC) in Douala, Cameroon: Providers Perspectives and Implications on Quality of HTC Services. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Irvine, C.J.; Vitoria, M.; Shaffer, N.; Muhe, L.M.; Negussie, E.K.; Doherty, M.C.; Ball, A.; Hirnschall, G. Developing the 2013 WHO Consolidated Antiretroviral Guidelines. AIDS 2014, 28, S93–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskew, J.; Turner, K.; Rø, G.; Ho, A.; Kimanga, D.; Sharif, S. Stage of HIV Presentation at Initial Clinic Visit Following a Community-Based HIV Testing Campaign in Rural Kenya. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF 2017. 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR241/SR241.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Stangl, A.L.; Brady, L.; Fritz, K. Measuring HIV Stigma and Discrimination. Available online: http://strive.lshtm.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/STRIVE%20stigma%20measurement.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Dorward, J.; Khubone, T.; Gate, K.; Ngobese, H.; Sookrajh, Y.; Mkhize, S.; Jeewa, A.; Bottomley, C.; Lewis, L.; Baisley, K.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on HIV Care in 65 South African Primary Care Clinics: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, I.V.; Walensky, R.P. Integrating HIV screening into routine health care in resource-limited settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, S77–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mills, E.J.; Kanters, S.; Hagopian, A.; Bansback, N.; Nachega, J.; Alberton, M.; Au-Yeung, C.G.; Mtambo, A.; Bourgeault, I.L.; Luboga, S.; et al. The financial cost of doctors emigrating from sub- Saharan Africa: Human capital analysis. BMJ 2011, 343, d7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machayo, J.A.; Keraro, V.N. Brain drain among health professionals in Kenya: A case of poor working conditions?—A critical review of the causes and effects. Prime J. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2013, 3, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda, E.L.; Hatzold, K.; Mugurungi, O.; Ncube, G.; Dupwa, B.; Siraha, P.; Madyira, L.K.; Mangwira, A.; Bhattacharya, G.; Cowan, F.M. An assessment of the Zimbabwe ministry of health and child welfare provider initiated HIV testing and counselling programme. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulzer, J.L.; Penner, J.A.; Marima, R.; Oyaro, P.; Oyanga, A.O.; Shade, S.B.; Blat, C.C.; Nyabiage, L.; Mwachari, C.W.; Muttai, H.C.; et al. Family model of HIV care and treatment: A retrospective study in Kenya. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2012, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwelunmor, J.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Okoror, T.A.; Brown, D.C.; BeLue, R. Family Systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2007, 27, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, J.; Bukusi, E.A.; Onono, M.; Holzemer, W.L.; Miller, S.; Cohen, C.R. HIV/AIDS Stigma and Refusal of HIV Testing Among Pregnant Women in Rural Kenya: Results from the MAMAS Study. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyamfi, E.; Okyere, P. Enoch, A.; Appiah-Brempong, E. Prevalence of, and barriers to the disclosure of HIV status to infected children and adolescents in a district of Ghana. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampofo, E.A.; Tetteh, I.C.; Adu-Gyamfi, R.; Enyan, N.I.E.; Agyare, E.; Addo, S.A.; Obiri-Yeboah, D. Family-Based Index testing for HIV; a qualitative study of acceptance, barriers/challenges and facilitators among clients in Cape Coast, Ghana. AIDS Care 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Amoako-Sakyi, D.; Baidoo, I.; AduOppong, A.; Rheinlander, T. The ‘fears’ of disclosing HIV status to sexual partners: A mixed Methods study in a counseling setting in Ghana. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, K.; van Damme, W. Scaling Up Access to Antiretroviral Treatment in Southern Africa: Who Will Do the Job? Lancet 2004, 364, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prah, J.; Hayfron-Benjamin, A.; Abdulai, M.; Lasim, O.; Nartey, Y.; Obiri-Yeboah, D. Factors Affecting Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV/AIDS Patients in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. J. HIV AIDS 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington-Edmans, F. People in Poorer Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean Adhere Better to HIV Treatment. Available online: https://www.avert.org/news/people-poorer-countries-latin-america-and-caribbean-adhere-better-hiv-treatment (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Mussini, C.; Antinori, A.; Bhagani, S.; Branco, T.; Brostrom, M.; Dedes, N.; Bereczky, T.; Girardi, E.; Gökengin, D.; Horban, A. European AIDS Clinical Society Standard of Care Meeting on HIV and Related Coinfections: The Rome Statements. HIV Med. 2016, 17, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangcuangco, L.M.A. HIV Crisis in The Philippines: Urgent Actions Needed. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.M.; Lief, E.; Donald, B.; Wilson, D.; Wilson, D.P. The Funding Landscape for HIV in Asia and the Pacific. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2015, 18, 20004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avert. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for Hiv Prevention. Available online: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Ending AIDS—Progress Towards the 90-90-90 Targets. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Global_AIDS_update_2017_en.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- Winter, S. Lost in Transition: Transgender People. Rights and HIV Vulnerability in the Asia-Pacific Region. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNDP_HIV_Transgender_report_Lost_in_Transition_May_2012.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Special Report. The Status of the HIV Response in the European Union/European Economic Area. 2016. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Status-of-HIV-response-in-EU-EEA-2016-30-jan-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- World Health Organization Global HIV/AIDS Response: Epidemic Update and Health Sector Progress Towards Uni-Versal Access: Progress Report 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44787/9789241502986_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- The Well Project. Stigma and Discrimination against Women Living with HIV. Available online: https://www.thewellproject.org/hiv-information/stigma-and-discrimination-against-women-living-hiv (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Bernard, E.J.; Cameron, S. Advancing HIV Justice 2: Building Momentum in Global Advocacy against HIV Criminalisation. Available online: https://www.hivjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/AHJ2.final2_.10May2016.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Human Rights Watch. “Swept Away”: Abuses against Sex Workers in China. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/05/14/swept-away/abuses-against-sex-workers-china# (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Criminalization and Ending the HIV Epidemic. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/criminalization-ehe.html (accessed on 23 November 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armstrong-Mensah, E.A.; Tetteh, A.K.; Ofori, E.; Ekhosuehi, O. Voluntary Counseling and Testing, Antiretroviral Therapy Access, and HIV-Related Stigma: Global Progress and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116597

Armstrong-Mensah EA, Tetteh AK, Ofori E, Ekhosuehi O. Voluntary Counseling and Testing, Antiretroviral Therapy Access, and HIV-Related Stigma: Global Progress and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116597

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmstrong-Mensah, Elizabeth Afibah, Ato Kwamena Tetteh, Emmanuel Ofori, and Osasogie Ekhosuehi. 2022. "Voluntary Counseling and Testing, Antiretroviral Therapy Access, and HIV-Related Stigma: Global Progress and Challenges" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116597

APA StyleArmstrong-Mensah, E. A., Tetteh, A. K., Ofori, E., & Ekhosuehi, O. (2022). Voluntary Counseling and Testing, Antiretroviral Therapy Access, and HIV-Related Stigma: Global Progress and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116597