Awe and Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Awe and Prosocial Behavior

1.2. Presence of Meaning in Life as a Mediator

1.3. Perceived Social Support as a Moderator

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Awe

2.2.2. Prosocial Behavior

2.2.3. The Presence of Meaning in Life

2.2.4. Perceived Social Support

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistic and Correlations

3.3. Testing for Mediation Effect

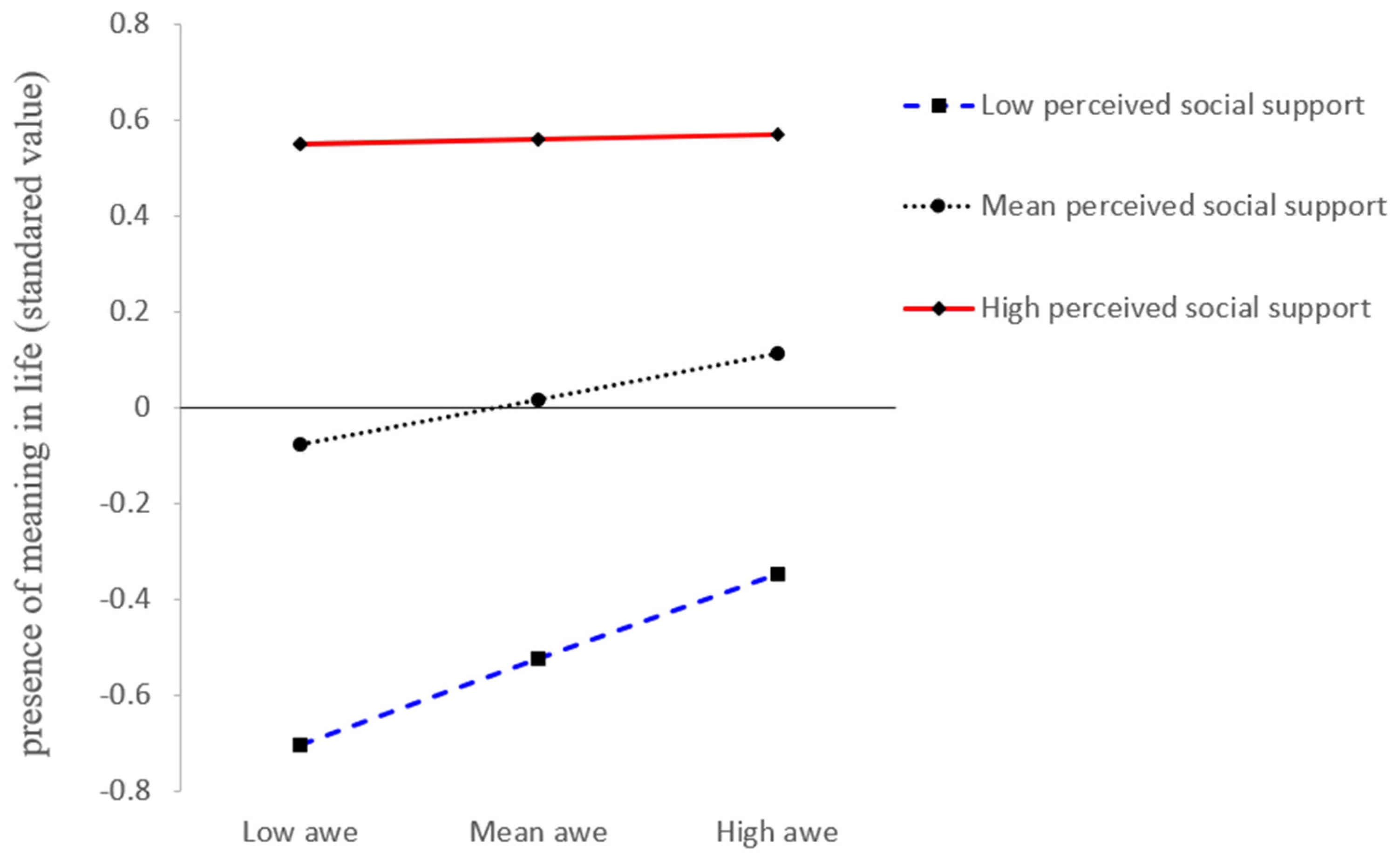

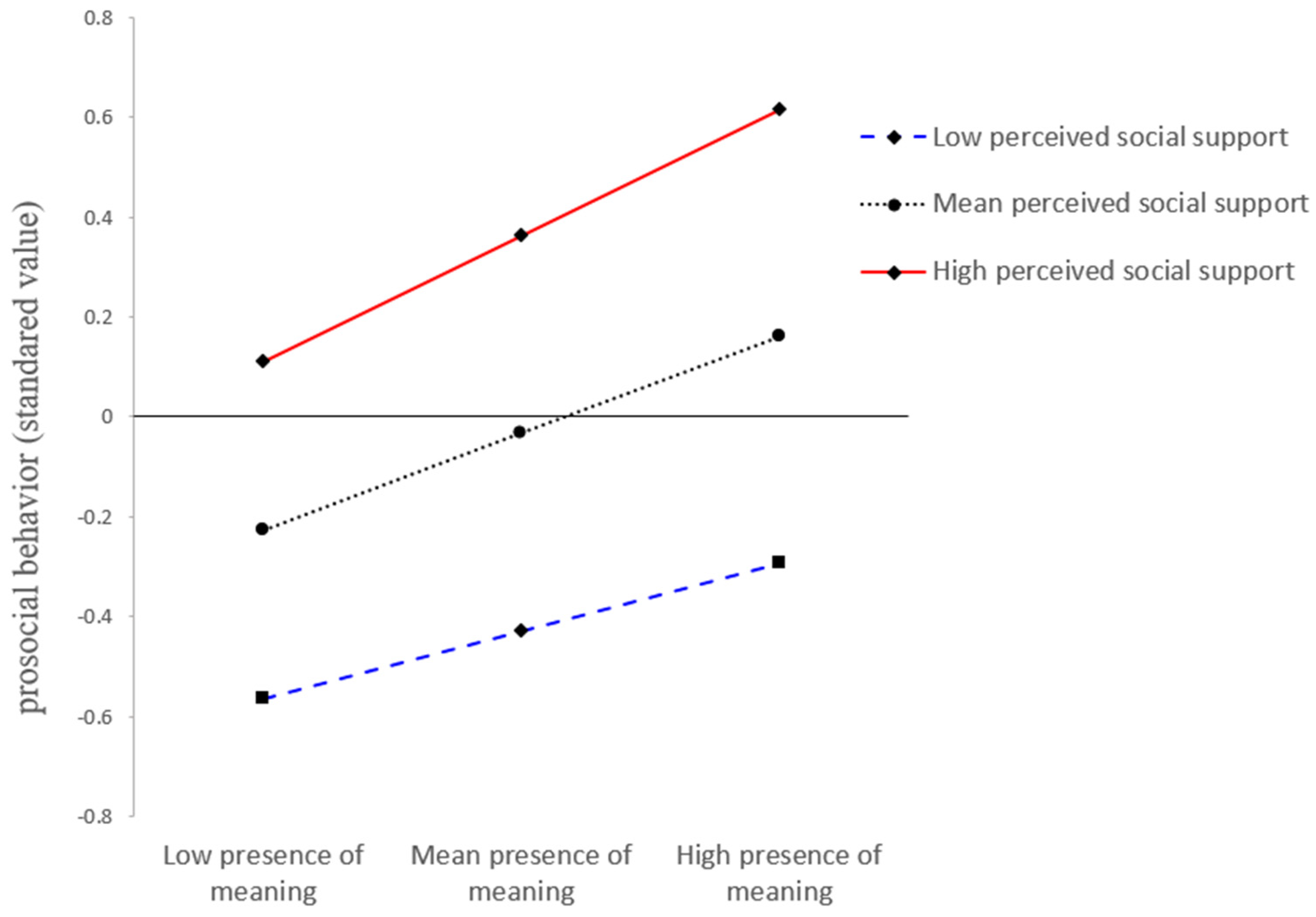

3.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Awe and Prosocial Behavior

4.2. The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life

4.3. The Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlo, G.; Randall, B.A. The Development of a Measure of Prosocial Behaviors for Late Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, S.Y. Considering the Reciprocal Relationship between Meaning in Life and Prosocial Behavior: A Cross-Lagged Analysis. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, A.; Plomin, R. Prosocial behavior from early to middle childhood: Genetic and environmental influences on stability and change. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Bauer, K.; Sengsavang, S. Fairness, prosociality, hypocrisy, and happiness: Children’s and adolescents’ motives for showing unselfish behaviour and positive emotions. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 37, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aknin, L.B.; Van de Vondervoort, J.W.; Hamlin, J.K. Positive feelings reward and promote prosocial behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.; Tucker, L.; Hornstein, H.A. The effects of social and nonsocial information on interpersonal behavior of males: The news makes news. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, C.; Saroglou, V. Awe’s effects on generosity and helping. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 11, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Dietze, P.; Feinberg, M.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shiota, M.N.; Thrash, T.M.; Danvers, A.; Dombrowski, J.T. Transcending the self: Awe, elevation, and inspiration. In Handbook of Positive Emotions; Tugade, M.M., Shiota, M.N., Kirby, L.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 362–377. [Google Scholar]

- Stellar, J.E.; Gordon, A.M.; Piff, P.K.; Cordaro, D.; Anderson, C.L.; Bai, Y.; Maruskin, L.A.; Keltner, D. Self-Transcendent Emotions and Their Social Functions: Compassion, Gratitude, and Awe Bind Us to Others Through Prosociality. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, R.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Xiong, X.; Lin, N.; Lian, R. Dispositional Awe and Online Altruism: Testing a Moderated Mediating Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.M.; Stillman, T.F.; Hicks, J.A.; Kamble, S.; Baumeister, R.; Fincham, F. To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hicks, J.A.; Trent, J.; Davis, W.E.; King, L.A. Positive affect, meaning in life, and future time perspective: An application of socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 2012, 27, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.; Vess, M.; Hicks, J.A.; Routledge, C. Awe and meaning: Elucidating complex effects of awe experiences on meaning in life. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 50, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, D.R.; Green, J.D.; Davis, D.E.; Hook, J.N.; Hulsey, T.L. Prosociality enhances meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 11, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. Longitudinal associations of meaning in life and psychosocial adjustment to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 26, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chirico, A.; Cipresso, P.; Yaden, D.B.; Biassoni, F.; Riva, G.; Gaggioli, A. Effectiveness of Immersive Videos in Inducing Awe: An Experimental Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Bao, T.; Liu, Y.; Passmore, H.-A. Elicited Awe Decreases Aggression. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2016, 10, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vötter, B.; Schnell, T. Cross-Lagged Analyses between Life Meaning, Self-Compassion, and Subjective Well-being among Gifted Adults. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Binder, M.; Freytag, A. Volunteering, subjective well-being and public policy. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-J.; Dou, K.; Wang, Y.-J.; Nie, Y.-G. Why Awe Promotes Prosocial Behaviors? The Mediating Effects of Future Time Perspective and Self-Transcendence Meaning of Life. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, R.-M.; Hong, Y.-J.; Xiao, H.-W.; Lian, R. Dispositional awe and prosocial tendency: The mediating roles of selftranscendent meaning in life and spiritual self-transcendence. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2020, 48, e9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülaçtı, F. The effect of perceived social support on subjective well-being. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 3844–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krause, N. Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychol. Aging 2007, 22, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobst, K.K.; Collins, R.L.; Embree, J.M. The Role of Emotion in Social Support Provision: Gender, Empathy and Expressions of Distress. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1994, 11, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, R.L.; Swenson, K.L.; Caserta, M.; Lund, D.; Devries, B. Feeling Lonely versus Being Alone: Loneliness and Social Support among Recently Bereaved Persons. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, M.G.; O’Brien, K.M. Psychological health and meaning in life stress, social support, and religious coping in latina/latino immigrants. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2007, 31, 204–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Bao, Z.; Wen, F. School Connectedness and Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Self-Control. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, M.; Belsky, J. Vantage sensitivity: Individual differences in response to positive experiences. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Sun, W.; Zhao, L.; Lai, X.; Zhou, Y. Parent-child attachment and prosocial behavior among junior high school students: Moderated mediation effect. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, M.T.; Thompson, N.J.; Kaslow, N.J. Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: The protective role of family relationships and social support. Soc. Psychiatry 2005, 40, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ye, B.J.; Ni, L.Y.; Yang, Q. Family Cohesion on Prosocial Behavior in College Students: Moderated Mediating Effect. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Groep, S.; Zanolie, K.; Green, K.H.; Sweijen, S.W.; Crone, E.A. A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy, and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, N.; Fatima, I.; Tariq, O. University students’ mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of resilience between meaning in life and mental well-being. Acta Psychol. 2022, 227, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, T. Perceived Social Support, Psychological Capital, and Subjective Well-Being among College Students in the Context of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Su, W.; Guo, X.; Tian, Z. The Impact of Awe Induced by COVID-19 Pandemic on Green Consumption Behavior in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.; Keltner, D.; John, O.P. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Hong, H.F.; Tan, C.; Li, L. Revisioning Prosocial Tendencies Measure for Adolescent. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2007, 23, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Xu, Y. Application of MLQ in High School Students from Earthquake-stricken and Non-stricken Area. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 19, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Burg, M.M.; Barefoot, J.; Williams, R.B.; Haney, T.; Zimet, G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 1987, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, Q.J.; Ren, Y.H. Correlation among Coping Style, Social Support and Psychosomatic Symptoms of Cancer Patients. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1996, 10, 160–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N. Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.; Fischer, R. How and when do personal values guide our attitudes and sociality? Explaining cross-cultural variability in attitude–value linkages. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1113–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, X.; Ren, Y. Mediator effects of positive emotions on social support and depression among adolescents suffering from mobile phone addiction. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.R.; Dodd, D. Student Burnout as a Function of Personality, Social Support, and Workload. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2003, 44, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Social Support and Academic Burnout Among University Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Y.; Bashirpur, M.; Khabbaz, M.; Hedayati, A.A. Comparison between Perfectionism and Social Support Dimensions and Academic Burnout in Students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeFreese, J.D.; Smith, A. Teammate social support, burnout, and self-determined motivation in collegiate athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | A T1 | PB T2 | PS T2 | MP T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A T1 | 1.00 | |||

| PB T2 | 0.192 *** | 1.00 | ||

| PS T2 | 0.218 *** | 0.519 *** | 1.00 | |

| MP T2 | 0.209 *** | 0.423 *** | 0.560 *** | 1.00 |

| M | 29.61 | 93.89 | 58.60 | 24.72 |

| SD | 5.75 | 16.21 | 13.35 | 5.14 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (PB T2) | Model 2 (MP T2) | Model 3 (PB T2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| gender | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 0.004 | 0.13 |

| A T1 | 0.19 | 5.09 *** | 0.21 | 5.57 *** | 0.11 | 3.06 ** |

| MP T2 | 0.40 | 11.25 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.19 | |||

| F | 13.04 *** | 15.86 *** | 52.48 *** | |||

| Predictors | Model 1 (MP T2) | Model 2 (PB T2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| gender | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| A T1 | 0.09 | 2.92 ** | 0.07 | 2.09 * |

| PS T2 | 0.54 | 16.77 *** | 0.40 | 10.07 *** |

| A T1 × PS T2 | −0.08 | −2.88 ** | ||

| MP T2 | 0.19 | 4.92 *** | ||

| MP T2 × PS T2 | 0.06 | 2.17 * | ||

| R2 | 0.33 | 0.30 | ||

| F | 82.74 *** | 58.46 *** | ||

| Level of PSS | Indirect Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (Mean − 1 SD) | 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.050 |

| Mean | 0.018 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.036 |

| High (Mean + 1 SD) | 0.003 | 0.011 | −0.020 | 0.024 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, Y.-N.; Feng, R.; Liu, Q.; He, Y.; Turel, O.; Zhang, S.; He, Q. Awe and Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116466

Fu Y-N, Feng R, Liu Q, He Y, Turel O, Zhang S, He Q. Awe and Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116466

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Ya-Nan, Ruodan Feng, Qun Liu, Yumei He, Ofir Turel, Shuyue Zhang, and Qinghua He. 2022. "Awe and Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116466

APA StyleFu, Y.-N., Feng, R., Liu, Q., He, Y., Turel, O., Zhang, S., & He, Q. (2022). Awe and Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of Presence of Meaning in Life and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116466