Alzheimer Caregiving Problems According to ADLs: Evidence from Facebook Support Groups

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Caregiver Burden

1.2. Use of Social Media for Healthcare Information Search

1.3. Social Media Caregiver Support

1.4. Effectiveness of Social Media Support

2. Methods

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

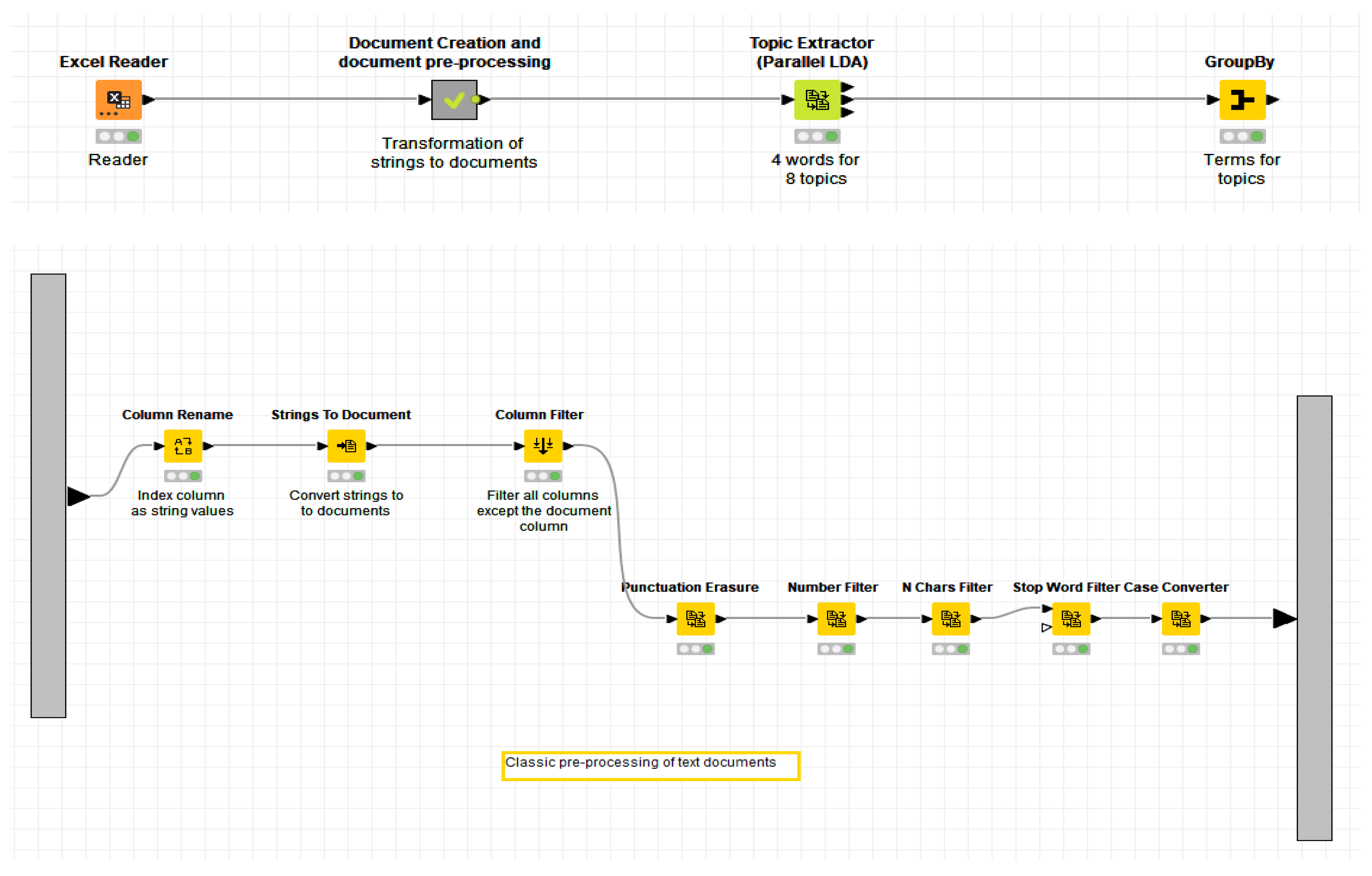

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Ethical Aspects of Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Dimension

3.1.1. Discussion Topics for the “Bathing” Activity

3.1.2. Discussion Topics for the “Dressing” Activity

3.1.3. Discussion Topics for the “Toileting” Activity

3.1.4. Discussion Topics for the “Transferring/Mobility” Activity

3.1.5. Discussion Topics for the “Continence” Activity

3.1.6. Discussion Topics for the “Feeding and Drinking” Activity

3.2. Quantitative Dimension

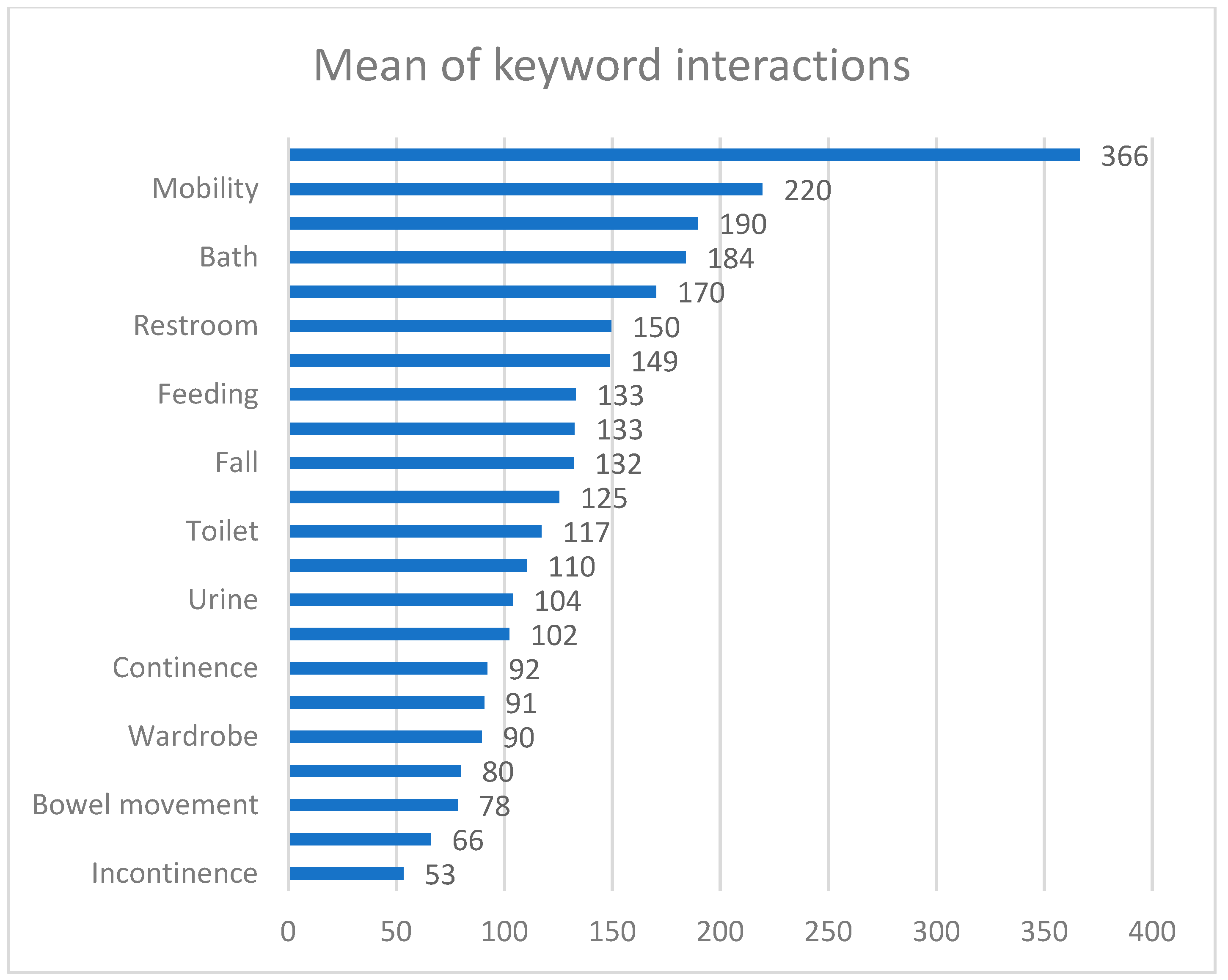

Engagement of Group Members with Content Related to the Individual ADLs

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Practical and Theoretical Implications and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saif, N.; Niotis, K.; Dominguez, M.; Hodes, J.F.; Woodbury, M.; Amini, Y.; Sadek, G.; Scheyer, O.; Caesar, E.; Hristov, H.; et al. Education Research: Online Alzheimer education for high school and college students: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2020, 95, e2305–e2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.; Budson, A. Current understanding of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and treatment. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bramboeck, V.; Moeller, K.; Marksteiner, J.; Kaufmann, L. Loneliness and Burden Perceived by Family Caregivers of Patients With Alzheimer Disease. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Dementias 2020, 35, 153331752091778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelker, L.S.; Browdie, R. Sidney Katz, MD: A New Paradigm for Chronic Illness and Long-Term Care. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuentes-García, A. Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3465–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A. (Ed.) Current Diagnosis & Treatment Geriatrics, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roley, S.S.; DeLany, J.V.; Barrows, C.J.; Brownrigg, S.; Honaker, D.; Sava, D.I.; Talley, V.; Voelkerding, K.; Amini, D.A.; Smith, E.; et al. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain & practice, 2nd ed. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2008, 62, 625–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smailhodzic, E.; Hooijsma, W.; Boonstra, A.; Langley, D.J. Social media use in healthcare: A systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abedin, T.; Al Mamun, M.; Lasker, M.A.; Ahmed, S.W.; Shommu, N.; Rumana, N.; Turin, T.C. Social Media as a Platform for Information About Diabetes Foot Care: A Study of Facebook Groups. Can. J. Diabetes 2017, 41, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, D.P.; Patil, S.; Benson, J.J.; Gage, A.; Washington, K.; Kruse, R.L.; Demiris, G. The Effect of Internet Group Support for Caregivers on Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Caregiver Burden: A Meta-Analysis. Telemed. e-Health 2017, 23, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, F.L.; Heinrich, S.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Schmidt, S.; Thyrian, J.R.; Schäfer-Walkmann, S.; Holle, B. Caregiver burden assessed in dementia care networks in Germany: Findings from the DemNet-D study baseline. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, C.; Giebel, C.; Bleijlevens, M.; Lethin, C.; Stolt, M.; Saks, K.; Soto, M.E.; Meyer, G.; Zabalegui, A.; Chester, H.; et al. Caring for a Person With Dementia on the Margins of Long-Term Care: A Perspective on Burden From 8 European Countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Associations of Stressors and Uplifts of Caregiving With Caregiver Burden and Depressive Mood: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2003, 58, P112–P128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallim, A.B.; Sayampanathan, A.A.; Cuttilan, A.; Ho, R.C.-M. Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Caregivers of Patients With Alzheimer Disease. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.-W.; Feld, S.; Dunkle, R.E.; Schroepfer, T.; Lehning, A. The Prevalence of Older Couples With ADL Limitations and Factors Associated With ADL Help Receipt. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2014, 58, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaingankar, J.A.; Chong, S.A.; Abdin, E.; Picco, L.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Zhang, Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Chua, B.Y.; Ng, L.L.; Prince, M.; et al. Care participation and burden among informal caregivers of older adults with care needs and associations with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Savundranayagam, M.Y.; Montgomery, R.J.V.; Kosloski, K. A Dimensional Analysis of Caregiver Burden Among Spouses and Adult Children. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Black, B.S.; Johnston, D.; Rabins, P.V.; Morrison, A.; Lyketsos, C.; Samus, Q.M. Unmet Needs of Community-Residing Persons with Dementia and Their Informal Caregivers: Findings from the Maximizing Independence at Home Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, R.E.; Feld, S.; Lehning, A.J.; Kim, H.; Shen, H.-W.; Kim, M.H. Does Becoming an ADL Spousal Caregiver Increase the Caregiver’s Depressive Symptoms? Res. Aging 2014, 36, 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, P. Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-T. Dementia Caregiver Burden: A Research Update and Critical Analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isik, A.T.; Soysal, P.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Bidirectional relationship between caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, D.R.; Brady, E.; Wilkerson, D.; Yi, E.-H.; Karanam, Y.; Callahan, C.M. Comparing Crowdsourcing and Friendsourcing: A Social Media-Based Feasibility Study to Support Alzheimer Disease Caregivers. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahrani, R.; Danilovich, M.K.; Liao, W.-K.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A. Analyzing Informal Caregiving Expression in Social Media. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–21 November 2017; pp. 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, D.A.; Brady, E.; Yi, E.-H.; Bateman, D.R. Friendsourcing Peer Support for Alzheimer’s Caregivers Using Facebook Social Media. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2018, 36, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoursiere, S.P. A Theory of Online Social Support. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2001, 24, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.G.; Hundt, E.; Dean, M.; Keim-Malpass, J.; Lopez, R. The Church of Online Support: Examining the Use of Blogs Among Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. J. Fam. Nurs. 2017, 23, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. Social media and health care professionals: Benefits, risks, and best practices. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 491–520. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, C. The experience of active involvement in an online Facebook support group, as a form of support for individuals who are diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. Tydskr. Vir Geesteswet. 2016, 56, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamm, M.P.; Chisholm, A.; Shulhan, J.; Milne, A.; Scott, S.D.; Given, L.M.; Hartling, L. Social media use among patients and caregivers: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robillard, J.; Johnson, T.W.; Hennessey, C.; Beattie, B.L.; Illes, J. Aging 2.0: Health Information about Dementia on Twitter. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.; Asuncion, A.; Smyth, P.; Welling, M. Distributed Algorithms for Topic Models. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1802–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Mimno, D.; McCallum, A. Efficient methods for topic model inference on streaming document collections. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Paris, France, 28 June–1 July 2009; pp. 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bachmann, P. Citizens’ Engagement on Regional Governments’ Facebook Sites. In Empirical Research from the Central Europe; University of Hradec Králové: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saari, T.; Hallikainen, I.; Hintsa, T.; Koivisto, A.M. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s disease: ALSOVA 5-year follow-up study. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 32, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Jin, Y.; Shi, Z.; Huo, Y.R.; Guan, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Ji, Y. The effects of behavioral and psychological symptoms on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical experience in China. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M.P.; Shave, K.; Gates, A.; Fernandes, R.; Scott, S.D.; Hartling, L. Which outcomes are important to patients and families who have experienced paediatric acute respiratory illness? Findings from a mixed methods sequential exploratory study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagervall, J.A.; Lag, M.R.; Brickman, S.; Ingram, R.E.; Feliciano, L. Give a piece of your mind: A content analysis of a facebook support group for dementia caregivers. Innov. Aging 2019, 3 (Suppl. S1), S850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Caregiver’s gender | 69.9% woman; 30.1% man |

| PAD’s gender | 64% woman; 34% man; 2% unknown |

| PAD’s relationship status towards the caregiver | 50% mother; 14% father; 10% wife/husband; 8% mother-/father-in-law; 4% grandparents; 4% uncle or aunt; 10% unknown |

| Caregiver’s country of residence | 95% United States; 1% United Kingdom; 1% Canada; 3% other countries or unknown |

| ADLs | N | Search Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Bathing/personal hygiene | 376 | bath, shower, clean |

| Dressing | 208 | dress, clothes, wardrobe, wear |

| Toileting | 299 | toilet, restroom, latrine |

| Transferring/mobility | 234 | transfer, shift, move, movement, transport, moving, mobility, motion, stairs |

| Continence | 284 | bowel movement, BM, incontinence, urine, continence, bowel, diapers |

| Feeding | 202 | eating, drinking, chewing, consuming, dining |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words * | Problems Mentioned in the Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: The need to wash/shower associated with the poor hygiene of PADs. | Mom, poo, help, told, towel, fight, months, don’t, anymore, remember, God, giving, nasty. | Bad hygiene/odor of the PAD. Frequency of bath/shower time. Relief that the PAD’s shower/bath was successfully finished. |

| 2: Refusing to have a bath. | Time, mom, help, day, bed, eyebrows, chair, refuses, stage, sign, standing, pooping, recommendation. | How to persuade a person to wash/take a shower. Mentioning the time since the last shower and determining the frequency of washing in others. A person is mean or agitated when asked to go to the shower. |

| 3: Repetitive bathroom visits. | Times, walk, soap, fall, husband, tonight, getting, water, bed, using, remember, mom, clothes, dementia, ready, day. | Bathing obsession. Falls related to frequent bathroom visits. |

| 4: Assistance during taking a bath. | Toilet, tried, help, morning, dad, day, woke, shampoo, loved, urine, porch, continue, assistance. | Higher need for assistance. Searching for tips how to simplify the process; where to find an external help. Lack of physical preparedness of the caregiver. Physical inability of the PAD to go to the bathroom. |

| 5: Insufficient cleanliness associated with advanced disease progression. | Smell, check, bad, diaper, hubby, bedroom, home, house, weeks, help, mom, clean, night, help, dad, hallucinating. | Bad odor and low overall hygiene of the house. Low hygiene/cleanliness in specific places in the house. |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words * | Problems Mentioned in the Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Suitable clothing. | Day, home, morning, night, people, can’t, fell, lives, grandad, nan, toilet, bath, depends, catheter, hospital. | Search for more comfortable clothes (without seams). Bad dressing choices. Anti-strip jumpsuits—recommendations. How to dress a person with a catheter or other health disadvantages. Constant undressing (including unsuitable/public places and situations). |

| 2: Burden associated with frequent laundry (including bed linen). | Ago, laundry, couple, towels, washing, daily, enjoyed, getting, stubborn, eating, close, independent, feel. | Time demands and financial costs associated with laundry (bed sheets, underwear, socks). Losing clothes. |

| 3: Dressing for special occasions. | Shower, day, mom, time, pearls, putting, else, dad, house, care, eat, various, finally, life. | Dressing for eating out, anniversaries. Using tracking wristbands as an accessory when leaving the house. |

| 4: Feeling cold. | Cold, reason, home, dementia, mom, stern, ready, trying, told, tried, head, underpants, stage, normal. | PADs’ demands for warm clothes. Caregivers’ concerns about PADs overheating. |

| 5: Refusal to change one’s clothes. | Bed, change, pajamas, told, turtleneck, laying, jeans, otherwise, time, depends, gone, bring, day, help, morning. | Staying the whole day in pajamas Refusing to wear nightwear. Refusing to dress. |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words | Problems Mentioned in the Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Toilet paper hoarding/stealing. | Paper, rolls, pants, found, pee, day, told, lol, wipe, started, time, putting, peed, depends, attempting, random, upset, husband. | Regular hoarding/hiding of toilet paper by PADs. Concerns of PADs that someone is stealing toilet paper. “Thefts” of toilet paper in a hospital facility. |

| 2: Issues with hygiene after using the toilet. | Help, father, trying, tried, issue, pants, understand, floor, seat, stand, pooping, night, concerned, pee. | Refusal to wipe after bowel movement; dirty toilet paper on the backside. Disposing of used toilet paper outside the toilet (bathroom bin). How to help PADs with wiping. |

| 3: Improper use of the toilet. | Roll, flushing, tissue, dementia, night, tonight, water, carpet, pull, hands, ago, day, times, weeks, care, bedroom. | Clogging the toilet bowl with toilet paper. Throwing various objects, clothes (underwear), and food into the toilet bowl. Repeated flushing. Fears of flooding; associated repair costs (plumber). |

| 4: Urinating/defecating outside of the toilet/bathroom. | Clean, else, help, advice, try, time, doing, stop, house, thank, ideas, trash, wipes, mother, helping, urinates, getting, dad. | Most often the bathroom bin or the bathroom floor. Various places in the house. Subsequent tracking of urine/stool around the house. |

| 5: Inability or refusal to go to the toilet. | Day, time, underwear, unit, poor, trying, feces, week, month, difficult, attention, soon, throughout, recently, UTI, test. | Consequences for caregivers, caregivers’ health concerns. Health consequences for PADs. Conflicts (verbal, physical) related to the problem. |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words * | Problems Mentioned In The Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Poor mobility on stairs. | Hand, morning, night, life, downstairs, time, husband, door, can’t, help, stairs, months, fast, force, keeping, angry, hold. | Falling on stairs due to bad balance. Waking up at night and walking around the house. Hallucinations and feelings of anger. PADs being angry with family members because they give them orders what to do. |

| 2: Decline in mobility, falling more often, refusing to use a walker. | Care, falling, spinal, dementia, doctors, stop, days, hospice, slow, pain, yesterday, causing, cane, walker, stroke, feet, front, hold, unable. | Falling from a wheelchair due to loss of mobility/stroke/feeling weak. Not being able to walk, hesitating to walk. |

| 3: Inability to move alone, need for hospital care, need for a wheelchair. | Home, nursing, dementia, fall, mobility, hospital, able, help, stage, looking, care, disease, days, eating, wheelchair, gone, suggestions, sleep, told. | Not being able to move to or from a wheelchair. Discussing other diseases connected with falling/not walking. Talking about when it is the right time to move the PAD to a hospital/hospice. |

| 4: Bathroom falls and night falls (stairs). | Weeks, Alzheimer, started, bathroom, night, help, falls, thank, week, hospital, please, dementia, found, days, brother, stages, call. | Feeling dizzy, paranoia, anxiety in everyday routine. Memory issues with basic tasks. |

| 5: Hurting legs after bad mobility/fall. | Dementia, time, walk, care, memory, falling, home, issues, feel, Alzheimer’s, legs, facility, don’t, term, living, mother, diagnosed, won’t. | Desperate about the situation (don not know what to do). Falling more often because of more severe stages. |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words * | Problems Mentioned in the Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Need to use continence wear. | Diapers, adult, time, suggestions, depends, help, night, issues, thank, stage, wear, overnight, thanks, looking, advice, skin, briefs, reason. | PADs get up at night and wander around the house. PADs refuse to use continence wear. Caregivers feeling desperate about “poop disaster”. |

| 2: Need surgery for incontinence problems. | Home, hospital, care, help, dementia, bowel, she’s, he’s, started, surgery, days, feel, lost, nursing, loved, stage, husband, doctor, family, ones. | Staying in hospital after surgery. Infection/fever/lungs/blocked bowel problems. |

| 3: Added more health problems after incontinence issues, need to be placed in a facility. | Dementia, care, sleep, memory, issues, person, time, people, help, change, facility, getting, caregiver, yesterday, times, diarrhea, health, dose | Unable to sleep. Don not recognize family members. Asking the group when it is time to move the PAD to a medical facility. |

| 4: Incontinence problems associated. with eating and drinking. | Bowel, days, time, hospice, movement, week, eating, home, mother, nurse, food, months, control, little, drink, she’s, morning, sometimes, weeks. | Forget to drink and eat/do not want to eat because of a sore throat. Urinating everywhere in the house. |

| 5: Constant urine problems, need to use continence wear, UTI. | Bowel, time, diapers, help, toilet, taking, clothes, getting, movement, morning, shower, else, floor, clean, advice, care, constantly, urine. | Asking the group what continence wear are the most suitable. Continence problems in shower. |

| Discussion Topic | Automatically Detected Discussion Words * | Problems Mentioned in the Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Losing weight. | Week, barely, stages, times, days, pounds, tube, meals, half, grandma, swallow, she’s, love, lost, dementia, trying. | Want to sleep instead of eating. Eat only one bite or take just a sip of water. |

| 2: Problems with swallowing. | Home, getting, nursing, stage, hospital, trying, Friday, stove, plate, meds, question, months, cancer, swallowing, sister, people. | Unable to chew or swallow because of pain. Caregivers share how the PAD passed away (share symptoms). PADs experience dry/sore throat. |

| 3: Stopped eating and drinking, sleep problems. | Time, hospice, care, dementia, weeks, days, doctor, night, yesterday, stopped, hospital, sleep, little, mother, past, disease, home. | Caregivers worry about the PAD dying because they refuse to eat and drink. PADs stay in bed for weeks. |

| 4: Forget about eating or drinking. | Water, sometimes, clothes, time, dinner, dementia, tell, coke, brain, lungs, mouth, break, hard, advice, tried, stages. | Do not remember their last meal/drink. Caregivers asking for advice how to make the PAD eat/drink. |

| 5: Having other health problems more or less connected with poor eating and drinking patterns. | Days, home, bathroom, time, she’s, night, able, started, weeks, cough, nurse, doing, little, maybe, hours, covid, blood. | Caregivers feeling desperate and frustrated about the PAD. Asking group when to move the PAD to a hospital or hospice. |

| ADLs Category | N | Likes per Post (Mean) | Comments per Post (Mean) | Overall Engagement (Mean) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing | 376 | 129.00 | 51.19 | 185.55 | 345.33185 | 17.80913 | 150.5349 | 220.5715 |

| Dressing | 208 | 58.07 | 32.38 | 111.46 | 234.19299 | 16.23836 | 79.4430 | 143.4705 |

| Toileting | 299 | 47.49 | 40.11 | 127.67 | 148.30209 | 8.57653 | 110.7940 | 144.5505 |

| Transferring | 234 | 133.85 | 34.24 | 133.29 | 359.78496 | 23.51988 | 86.9475 | 179.6251 |

| Continence | 284 | 49.08 | 38.63 | 117.77 | 176.98192 | 10.50195 | 97.0993 | 138.4430 |

| Feeding | 202 | 308.37 | 49.05 | 217.4158 | 492.07714 | 34.62243 | 149.1461 | 285.6856 |

| In total | 1603 | 59.7 | 39.7 | 149.5190 | 308.56894 | 7.70700 | 134.4022 | 164.6359 |

| Bathing | Dressing | Toileting | Transferring | Continence | Feeding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing | X | 0.079 | 0.225 | 0.614 | 0.075 | 1 |

| Dressing | 0.079 | X | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.007 * |

| Toileting | 0.225 | 1 | X | 1 | 1 | 0.020 * |

| Transferring | 0.614 | 1 | 1 | X | 1 | 0.065 |

| Continence | 0.075 | 1 | 1 | 1 | X | 0.006 * |

| Feeding | 1 | 0.007 * | 0.020 * | 0.065 | 0.006 * | X |

| Bathing | advanced disease progression + rejection of bath/shower → need of assistance during taking a bath + and/or insufficient home cleanliness → lower personal hygiene of PAD |

| Dressing | feeling cold + refusal to change clothes → lower personal hygiene of PAD |

| Toileting | improper use of toilet (repetitive flushing, throwing objects or clothes into the toilet) + toilet paper hoarding/stealing → financial concerns low personal hygiene after the use of toilet + urination and defecation outside the toilet → lower personal hygiene of PAD → insufficient home cleanliness |

| Transferring | refusing to use a walker + and/or stairs/bathroom/night falls → not able to move alone + hurting legs after mobility/fall → not able to move alone → need of a wheelchair + and/or need of hospital care |

| Continence | constant urine problems + problems associated with feeding and drinking → incontinence problems → need to use continence wear + and/or need of hospital care + UTI treatment or surgery |

| Feeding and drinking | problems with swallowing + and too much sleeping + low nutrition of received food → loss of weight → concerns of caregivers on proper feeding and drinking |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachmann, P.; Hruska, J. Alzheimer Caregiving Problems According to ADLs: Evidence from Facebook Support Groups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116423

Bachmann P, Hruska J. Alzheimer Caregiving Problems According to ADLs: Evidence from Facebook Support Groups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116423

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachmann, Pavel, and Jan Hruska. 2022. "Alzheimer Caregiving Problems According to ADLs: Evidence from Facebook Support Groups" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116423

APA StyleBachmann, P., & Hruska, J. (2022). Alzheimer Caregiving Problems According to ADLs: Evidence from Facebook Support Groups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116423