The Prospective Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (PCRS) for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual People: Preliminary Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Coparenting Relationship

1.2. Coparenting, Social Support, and Stigma

1.3. Measurement of Coparenting

1.4. The Present Study

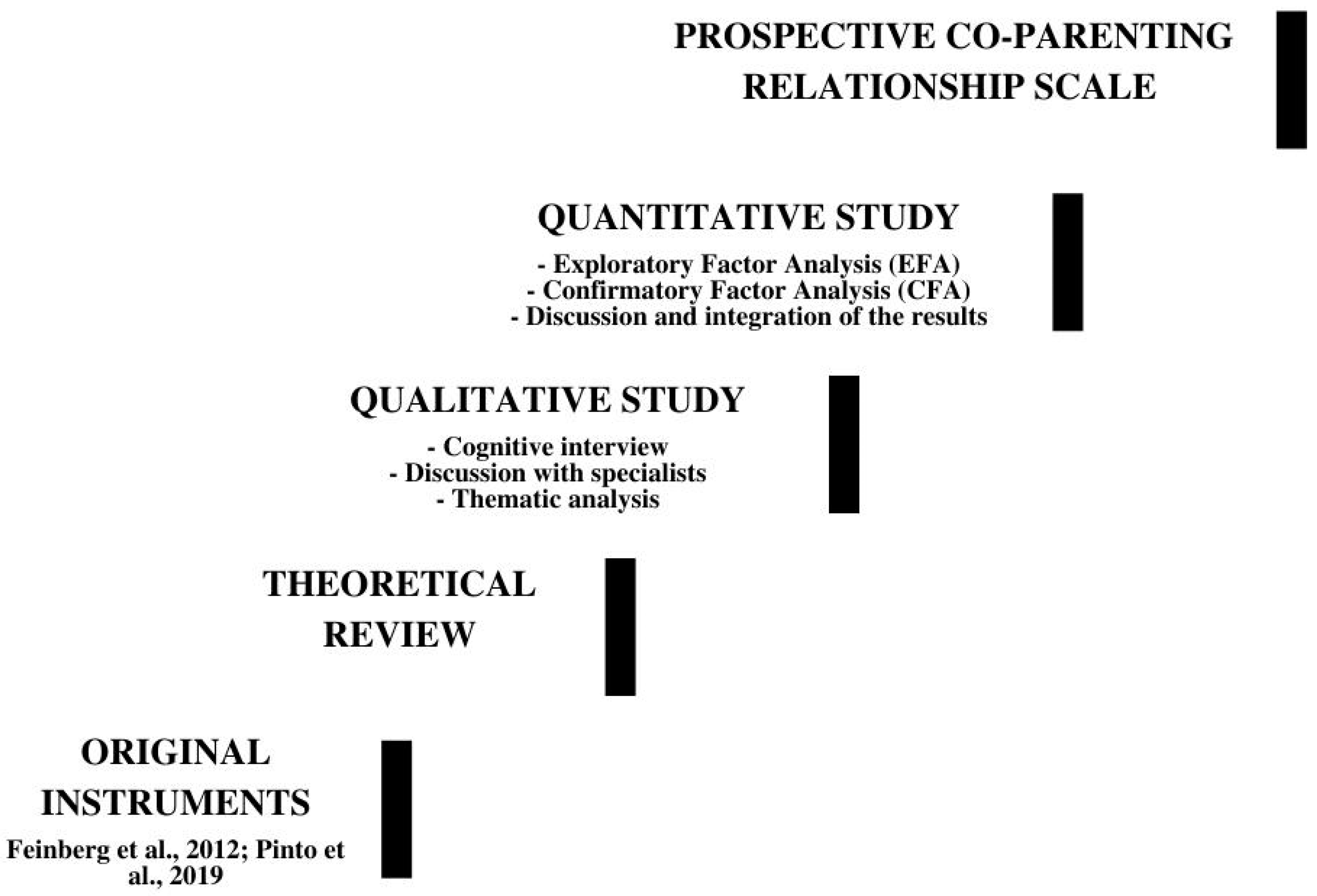

2. Materials and Methods (Study 1)

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure of Data Collection

2.4. Procedure of Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive Interviews

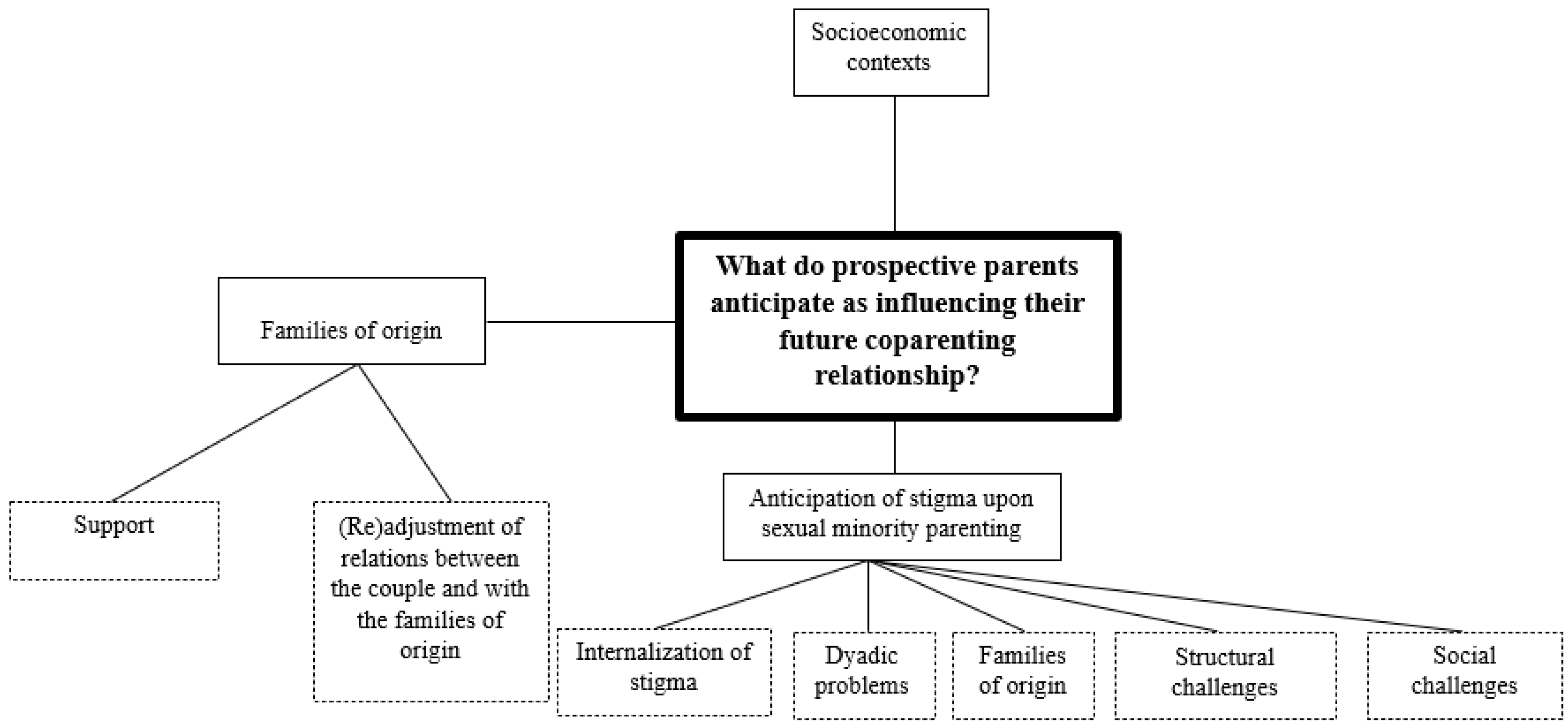

3.2. Thematic Analysis

4. Materials and Methods (Study 2)

4.1. Participants

4.2. Procedure

4.3. Measures

5. Results

5.1. EFA with the Heterosexual Sample

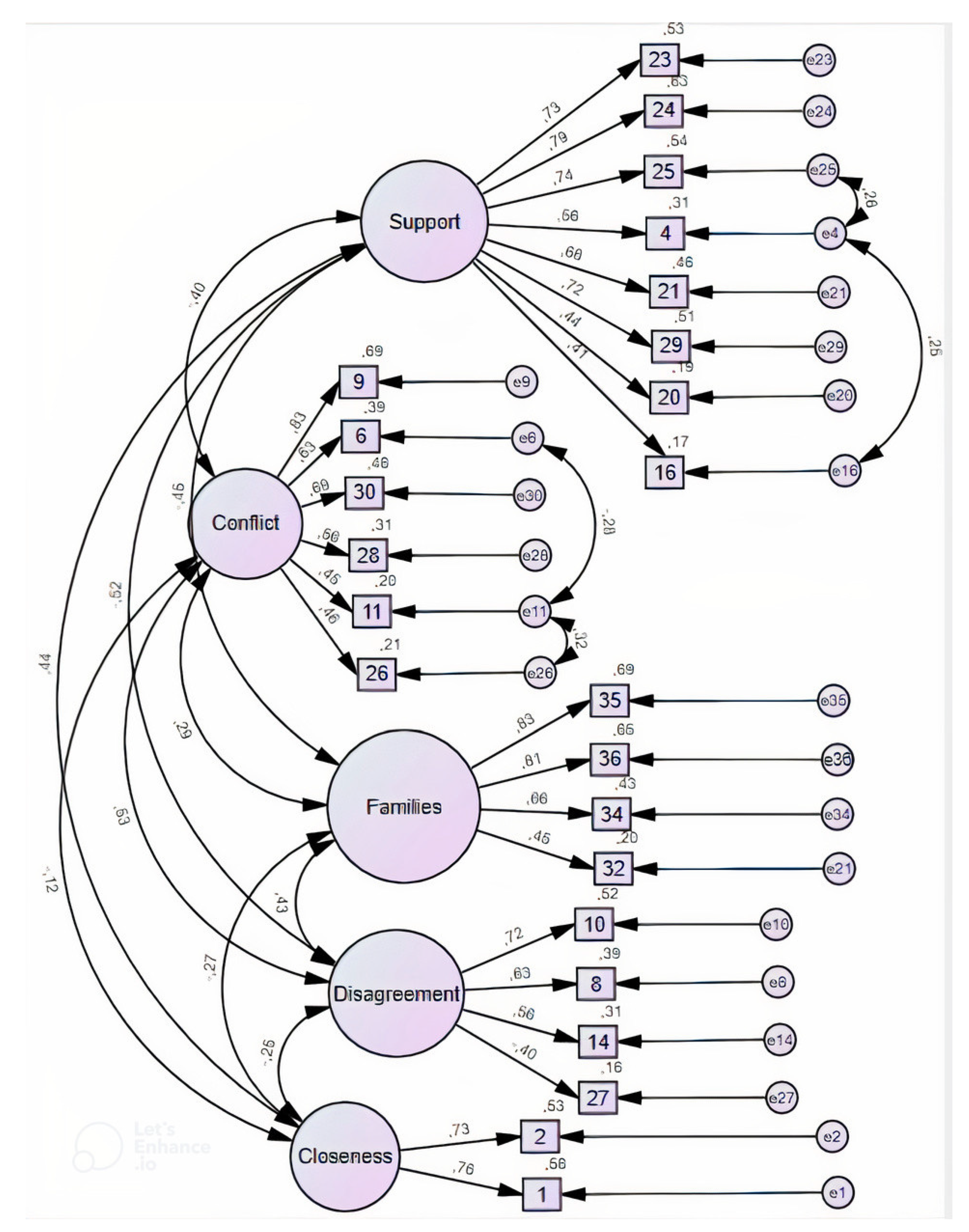

5.2. CFA with Heterosexual Sample

5.3. EFA with Sexual Minority Sample

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Instruments and Dimensions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | PCRS—Version for Sexual Minority Persons [23] | PCRS—Version for Heterosexual Persons [23] | CRS—PV [12] | CRS [2] |

| (23) When I am at my wits end as a parent, my partner will give me extra support I will need. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (22) My partner will appreciate how hard I will work at being a good parent. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (4) My partner will pay a great deal of attention to our child. | Coparenting Support | ------------ | Coparenting Support | Endorse Partner Parenting |

| (25) I believe my partner will be a good parent. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Endorse Partner Parenting |

| (21) We will grow and mature together through our experiences as parents. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Closeness |

| (29) My partner will tell me I am doing a good job or otherwise will let me know I am being a good parent. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (20) My partner will be willing to make personal sacrifices to help taking care of our child. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Endorse Partner Parenting |

| (24) My partner will make me feel like I am the best possible parent for our child. | Coparenting Support | ----------------------- | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (16) My partner will have a lot of patience with our child. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Endorse Partner Parenting |

| (3) My partner will ask my opinion on parenting issues. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (27) My partner and I will have the same goals for our child. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Agreement |

| (1) Parenting will give us a focus for the future. | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Closeness | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Closeness |

| (2) My relationship with my partner will be stronger after having a child. | ------------- | Coparenting Closeness | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Closeness |

| (13) My partner will be sensitive to our child’s feelings and needs. | Coparenting Support | --------- | Coparenting Support | Endorse Partner Parenting |

| (18) When all three of us will be together, my partner sometimes will compete with me for our child’s attention. | Coparenting Undermining | --------- | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Undermining |

| (15) My partner will try to show that she or he is better than me at caring for our child. | Coparenting Undermining | ------------- | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Undermining |

| (11) My partner sometimes will make jokes or sarcastic comments about the way I will be as a parent. | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Undermining |

| (19) My partner will undermine my parenting. | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Undermining |

| (7) It will be easier and funnier to play with the child alone than with my partner. | Coparenting Undermining | ------------------ | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Undermining |

| (26) Sometimes, I will find myself in a mildly tense or sarcastic interchange with my partner. | Coparenting Undermining | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Conflict | Exposure to Conflict |

| (28) We will argue about our relationship or marital issues unrelated to our child, in the child’s presence. | ----------------------- | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Conflict | Exposure to Conflict |

| (5) My partner will like to play with our child and then he/she will leave the dirty work to me. | Coparenting Undermining | --------------- | Coparenting Disagreement | Division of Labor |

| (8) My partner and I will have different ideas about how to raise our child. | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Agreement |

| (14) My partner and I will have different standards for our child’s behaviour. | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Agreement |

| (39) My partner will have difficulties in coping with if our child is discriminated because of our sexual orientation. | Coparenting Disagreement | ------------------- | ------------------ | ------------------- |

| (9) Sometimes, one or both of us will say cruel or hurtful things to each other in front of the child. | Coparenting Disagreement | -------------------- | -------------------- | Exposure to Conflict |

| (43) It will be harder to be parents if our family does not support our sexual orientation. | Coparenting Disagreement | -------------------- | ----------------- | --------------------- |

| (10) We will have different ideas regarding our child’s eating and sleeping habits and other routines. | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Agreement |

| (6) We will argue about our child in the child’s presence. | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Conflict | Coparenting Conflict | Exposure to Conflict |

| (34) We will disagree about who will take care of our child: my parents or his/her parents. | Conflict with Families of Origin | Conflict with Families of Origin | --------------------- | ---------------------- |

| (36) Our relationship will wear off with the interference of our parents in the way we raise our child. | Conflict with Families of Origin | Conflict with Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (32) The financial help provided by our parents will be a motive of disagreement between me and my partner. | Conflict with Families of Origin | Conflict with Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (35) The way each of our families raise children will be a motive of conflict between me and my partner. | Conflict with Families of Origin | Conflict with Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (42) My partner will be less comfortable in raising our child because of not having a female/male role model at home. | Conflict with Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (47) It will be easy to find health professionals who do not discriminate LGBT families. | Institutional Support | --------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (46) It will be easy to find a school, which accepts all family types. | Institutional Support | ---------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (48) It will be easy to teach our child how to deal with prejudice. | Institutional Support | --------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (45) Because they are not expecting us to have a child, our parents will provide us less support in the education of our child. | Support from Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (41) After having a child, our family will support us as parents. | Support from Families of Origin | ------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (37) Spending more time with our families of origin after being parents will improve our relationship. | Support from Families of Origin | ---------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (33) My partner will accept the tips that my parents will give about childcare. | Support from Families of Origin | --------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (31) It will be easier to raise a child if we have our parents’ support. | Support from Families of Origin | ---------------------- | --------------------- | --------------------- |

| (12) My partner will not trust my abilities as a parent. | ---------------------- | ---------------------- | Coparenting Disagreement | Coparenting Undermining |

| (17) We will often discuss the best way to meet our child’s needs. | ---------------------- | ---------------------- | Coparenting Support | Coparenting Support |

| (9) Sometimes, one or both of us will say cruel or hurtful things to each other in front of the child. | ---------------------- | ---------------------- | Coparenting Support | Exposure to Conflict |

| (30) We will yell at each other within earshot of the child. | ---------------------- | ---------------------- | Coparenting Conflict | Exposure to Conflict |

References

- Feinberg, M.E. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parent Sci. Pract. 2003, 3, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Brown, L.D.; Kan, M.L. A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting 2012, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Teti, D.M.; Feinberg, M.E. Predicting coparenting quality in daily life in mothers and fathers. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C.J.; Farr, R.H. Coparenting among lesbian and gay couples. In Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems; McHale, J.P., Lindahl, K.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.; Baker, J.; Radunovich, H.L. When people parent together: Let’s talk about coparenting. In EDIS; University of Florida, IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren, L.A.; Hawkins, D.P. Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. J. Adult Dev. 2004, 11, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; McDaniel, B.T.; Leavitt, C.E.; Feinberg, M.E. Longitudinal associations between relationship quality and coparenting across the transition to parenthood: A dyadic perspective. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.E.; Jacobvitz, D.B.; Hazen, N.L. What’s so bad about competitive coparenting? Family-level predictors of children’s externalizing symptoms. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1684–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durtschi, J.A.; Soloski, K.L.; Kimmes, J. The dyadic effects of supportive coparenting and parental stress on relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, M.E.; Petren, R.E. A qualitative examination of coparenting among foster parent dyads. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Lopes, F.; Bernard, M.; Frascarolo, F.; Lavanchy Scaiola, C.; Corboz-Warnery, A.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. The development of family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and child outcomes at 5 years. Fam. Process. 2012, 51, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.M.; Figueiredo, B.; Feinberg, M.E. The coparenting relationship scale—Father’s prenatal version. J. Adult Dev. 2019, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Smith, J.Z.; Perry-Jenkins, M. The division of labor in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual new adoptive parents. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, R.H.; Bruun, S.T.; Patterson, C.J. Longitudinal associations between coparenting and child adjustment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parent families. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 2547–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumontha, J.; Farr, R.H.; Patterson, C.J. Social support and coparenting among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzer, N.K.; Sim, C.Q. Adapting instruments for use in multiple languages and cultures: A review of the ITC Guidelines for Test Adaptations. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 1999, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, N.; Baiocco, R.; Ioverno, S.; Chirumbolo, A.; Lingiardi, V. Same-sex parent families in Italy: Validation of the Coparenting Scale-Revised for lesbian mothers and gay fathers. Eur. J. Dev. 2017, 14, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.P. Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 31, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, J.A. How statewide LGB policies go from “under our skin” to “into our hearts”: Fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being among emerging adult sexual minority men. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gato, J.; Santos, S.; Fontaine, A.M. To have or not to have children? That is the question. Factors influencing parental decisions among lesbians and gay men. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2017, 14, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gato, J.; Leal, D.; Coimbra, S.; Tasker, F. Anticipating parenthood among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual young adults without children in Portugal: Predictors and profiles. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, D.; Gato, J.; Tasker, F. Prospective parenting: Sexual identity and intercultural trajectories. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, D.; Gato, J.; Coimbra, S.; Freitas, D.; Tasker, F. Social support in the transition to parenthood among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons: A systematic review. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 18, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.A.; Mortensen, J.A.; Gonzalez, H.; Gonzalez, J.M. Cultural factors moderating links between neighborhood disadvantage and parenting and coparenting among Mexican origin families. In Child Youth Care Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 45, pp. 927–945. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, T. Minorities and Discrimination in Indonesia: The Legal Framework. In Contentious Belonging: The Place of Minorities in Indonesia; ISEAS Publishing: Singapore, 2019; pp. 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shenkman, G.; Gato, J.; Tasker, F.; Erez, C.; Leal, D. Deciding to parent or remain childfree: Comparing sexual minority and heterosexual childless adults from Israel, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second Edition). Int. J. Test. 2018, 18, 101–134. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 2307-0919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.P.; Negrini, L.; Sirotkin, Y. Coparenting. In APA Handbook of Contemporary Family Psychology: Foundations, Methods, and Contemporary Issues across the Lifespan; Fiese, B.H., Celano, M., Deater-Deckard, K., Jouriles, E.N., Whisman, M.A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2019; pp. 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.W.; Ermisch, J. Proximity of couples to parents: Influences of gender, labor market, and family. Demography 2015, 52, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Egeren, L.A. Prebirth predictors of coparenting experiences in early infancy. Infant Ment. Health J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2003, 24, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletti, A.T.; Scorsolini-Comin, F. Marital relationship and expectations about parenthood in gay couples. Psicol. Teor. prát. 2015, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Sayer, A. Lesbian couples’ relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Frizzo, G.B.; Piccinini, C.A. Coparenting across the transition to parenthood: Qualitative evidence from South-Brazilian families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkman, G. Anticipation of stigma upon parenthood impacts parenting aspirations in the LGB community in Israel. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 18, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Smalling, S.; Groza, V.; Ryan, S. The experiences of gay men and lesbians in becoming and being adoptive parents. Adopt. Q. 2009, 12, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; Steele, L.; Sapiro, B. Perceptions of predisposing and protective factors for perinatal depression in same-sex parents. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2005, 50, e65–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G. Making room for daddies: Male couples creating families through adoption. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2011, 7, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, M.; Preto, N.A.G.; Carter, B.A. The Expanding Family Life Cycle: Individual, Family, and Social Perspectives, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, T.R.D.; Barham, E.J.; Souza, C.D.D.; Böing, E.; Crepaldi, M.A.; Vieira, M.L. Cross-cultural adaptation of an instrument to assess coparenting: Coparenting Relationship Scale. Psico-USF 2018, 23, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamela, D.; Morais, A.; Jongenelen, I. Validação psicométrica da Escala da Relação Coparental em mães portuguesas. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2018, 36, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using Ibm Spss Statistics+ Webassign, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive interviewing in practice: Think-aloud, verbal probing and other techniques. In Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005; pp. 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, D.; Hodgen, J.; Lamesoo, K.; Kõiv, P.; Tolboom, J. Think aloud: Using cognitive interviewing to validate the PISA assessment of student self-efficacy in mathematics. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2018, 41, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. In Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2016; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2020; p. 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality. Manual de Linguagem Inclusiva. Conselho Económico e Social; CES: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. Available online: https://www.cig.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/12-Manual-de-Linguagem-Inclusiva-CES.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Yardley, L. Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. Qual. Psychol. A Pract. Guide Res. Methods 2008, 2, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaterra, F.; Veríssimo, M. A adopção: O Direito e os afectos Caracterização das famílias adoptivas do Distrito de Lisboa. Anal. Psicol. 2008, 26, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little jiffy, mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1950, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; Continuum International Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis for Social Statistics. Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In Handbook of Methodological Innovation; Williams, M., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin, D.J. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedure, 5th ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics; ReportNumber, Lda: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; p. 10694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Foster, C.A. Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S. Gender Role Models … who needs ’em?! Qual. Soc. Work 2008, 7, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gato, J.; Leal, D.; Biasutti, C.; Tasker, F.; Fontaine, A.M. Building a Rainbow Family: Parenthood Aspirations of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender/Gender Diverse Individuals. In Parenting and Couple Relationships among LGBTQ+ People in Diverse Contexts; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Quiroz, F.; Costa, P.A.; Lozano-Verduzco, I. Parenting aspiration among diverse sexual orientations and gender identities in Mexico, and its association with internalized homo/transnegativity and connectedness to the LGBTQ community. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 41, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polivanova, K.N. Modern parenthood as a subject of research. Russ. Educ. Soc. 2018, 60, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, C. The ambivalent familism of the Italian welfare state. Soc. Polit. 1994, 1, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.; McGoldrick, M. Bereavement: A family life cycle perspective. Fam. Sci. 2013, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Smith, J.Z. Preschool selection considerations and experiences of school mistreatment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). A Long Way to Go for LGBTI Equality—Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P. Social desirability bias. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Sheth, J., Malhotra, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.; Morgan, G. Same-sex parents’ experiences of schools in England. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2019, 15, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornello, S.L.; Patterson, C.J. Timing of parenthood and experiences of gay fathers: A life course perspective. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2015, 11, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Brown, S.L.; Schrader-Mcmillan, A. Parenting for mental health: What does the evidence say we need to do? Report of Workpackage 2 of the DataPrev project. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, i10–i28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Mangelsdorf, S.C. Parent characteristics and early coparenting behavior at the transition to parenthood. Soc. Dev. 2012, 2, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stright, A.D.; Bales, S.S. Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Fam. Relat. 2003, 52, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Riggs, S.; Kaminski, P. Role of marital adjustment in associations between romantic attachment and coparenting. Fam. Relat. 2017, 66, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Age | Residence | Gender | Sexual Orientation | Gender Identity | Educational Attainment | Marital Status | Employment Status | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JDA | 41 | Major city | Feminine | Bisexual | Woman | Master | Living together * | Part-time | Portuguese |

| Luís | 45 | Major city | Masculine | Gay | Man | Master | Living together * | Full-time | Portuguese |

| Castro | 28 | Town | Masculine | Gay | Man | Master | Living apart together ** | Unemployed | Portuguese |

| Isabel | 38 | Major city | Feminine | Heterosexual | Woman | Master | In a civil union | Full-time | Portuguese |

| CG | 29 | Town | Feminine | Heterosexual | Woman | Master | Cohabitation | Full-time | Portuguese |

| Renato | 26 | Town | Masculine | Heterosexual | Man | High school | Living apart together ** | Full-time | Portuguese |

| Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (22) My partner will appreciate how hard I will work at being a good parent. | 0.774 | ||||

| (23) When I am at my wits end as a parent, my partner will give me extra support I will need. | 0.763 | ||||

| (24) My partner will make me feel like I am the best possible parent for our child. | 0.713 | ||||

| (21) We will grow and mature together through our experiences as parents. | 0.676 | ||||

| (25) I believe my partner will be a good parent. | 0.650 | ||||

| (4) My partner will pay a great deal of attention to our child. | 0.630 | ||||

| (29) My partner will tell me I am doing a good job or otherwise will let me know I am being a good parent. | 0.597 | ||||

| (3) My partner will ask my opinion on parenting issues. | 0.581 | ||||

| (19) My partner will undermine my parenting. | 0.572 | ||||

| (13) My partner will be sensitive to our child’s feelings and needs. | 0.537 | ||||

| (20) My partner will be willing to make personal sacrifices to help taking care of our child. | 0.535 | ||||

| (16) My partner will have a lot of patience with our child. | 0.497 | ||||

| (7) It will be easier and funnier to play with the child alone than with my partner. | 0.473 | ||||

| (8) My partner and I will have different ideas about how to raise our child. | 0.699 | ||||

| (10) We will have different ideas regarding our child’s eating and sleeping habits and other routines. | 0.660 | ||||

| (9) Sometimes, one or both of us will say cruel or hurtful things to each other in front of the child. | 0.654 | ||||

| (30) We will yell at each other within earshot of the child. | 0.647 | ||||

| (6) We will argue about our child in the child’s presence. | 0.636 | ||||

| (14) My partner and I will have different standards for our child’s behaviour. | 0.595 | ||||

| (26) Sometimes, I will find myself in a mildly tense or sarcastic interchange with my partner. | 0.504 | ||||

| (28) We will argue about our relationship or marital issues unrelated to our child, in the child’s presence. | 0.493 | ||||

| (11) My partner sometimes will make jokes or sarcastic comments about the way I will be as a parent | 0.523 | ||||

| (27) My partner and I will have the same goals for our child. | 0.500 | ||||

| (35) The way each of our families raise children will be a motive of conflict between me and my partner. | 0.789 | ||||

| (36) Our relationship will wear off with the interference of our parents in the way we raise our child. | 0.719 | ||||

| (34) We will disagree about who will take care of our child: my parents or his/her parents. | 0.631 | ||||

| (32) The financial help provided by our parents will be a motive of disagreement between me and my partner. | 0.622 | ||||

| (2) My relationship with my partner will be stronger after having a child. | 0.733 | ||||

| (1) Parenting will give us a focus for the future. | 0.661 | ||||

| (33) My partner will accept the tips that my parents will give about childcare. | 0.751 | ||||

| (31) It will be easier to raise a child if we have our parents’ support. | 0.634 | ||||

| (37) Spending more time with our families of origin after being parents will improve our relationship. | 0.621 | ||||

| Subscale | Cronbach’s Alphas (α) |

|---|---|

| Coparenting Support | 0.844 |

| Coparenting Conflict | 0.833 |

| Conflict Families of Origin | 0.717 |

| Coparenting Closeness | 0.758 |

| Positive Influence of Families of Origin | 0.499 |

| Factors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| (23) When I am at my wits end as a parent, my partner will give me extra support I will need. | 0.791 | |||||

| (22) My partner will appreciate how hard I will work at being a good parent. | 0.778 | |||||

| (4) My partner will pay a great deal of attention to our child. | 0.752 | |||||

| (25) I believe my partner will be a good parent. | 0.746 | |||||

| (21) We will grow and mature together through our experiences as parents. | 0.696 | |||||

| (29) My partner will tell me I am doing a good job or otherwise will let me know I am being a good parent. | 0.693 | |||||

| (20) My partner will be willing to make personal sacrifices to help taking care of our child. | 0.692 | |||||

| (24) My partner will make me feel like I am the best possible parent for our child. | 0.689 | |||||

| (16) My partner will have a lot of patience with our child. | 0.600 | |||||

| (3) My partner will ask my opinion on parenting issues. | 0.584 | |||||

| (27) My partner and I will have the same goals for our child. | 0.544 | |||||

| (1) Parenting will give us a focus for the future. | 0.513 | |||||

| (13) My partner will be sensitive to our child’s feelings and needs. | 0.511 | |||||

| (18) When all three of us will be together, my partner sometimes will compete with me for our child’s attention. | 0.749 | |||||

| (15) My partner will try to show that she or he is better than me at caring for our child. | 0.735 | |||||

| (11) My partner sometimes will make jokes or sarcastic comments about the way I will be as a parent. | 0.551 | |||||

| (19) My partner will undermine my parenting. | 0.546 | |||||

| (7) It will be easier and funnier to play with the child alone than with my partner. | 0.506 | |||||

| (26) Sometimes, I will find myself in a mildly tense or sarcastic interchange with my partner. | 0.487 | |||||

| (5) My partner will like to play with our child and then he/she will leave the dirty work to me. | 0.414 | |||||

| (8) My partner and I will have different ideas about how to raise our child. | 0.665 | |||||

| (14) My partner and I will have different standards for our child’s behaviour. | 0.565 | |||||

| (39) My partner will have difficulties in coping with if our child is discriminated because of our sexual orientation. | 0.528 | |||||

| (9) Sometimes, one or both of us will say cruel or hurtful things to each other in front of the child. | 0.491 | |||||

| (43) It will be harder to be parents if our family does not support our sexual orientation. | 0.457 | |||||

| (10) We will have different ideas regarding our child’s eating and sleeping habits and other routines. | 0.448 | |||||

| (6) We will argue about our child in the child’s presence. | 0.414 | |||||

| (34) We will disagree about who will take care of our child: my parents or his/her parents. | 0.806 | |||||

| (36) Our relationship will wear off with the interference of our parents in the way we raise our child. | 0.640 | |||||

| (32) The financial help provided by our parents will be a motive of disagreement between me and my partner. | 0.613 | |||||

| (35) The way each of our families raise children will be a motive of conflict between me and my partner. | 0.565 | |||||

| (42) My partner will be less comfortable in raising our child because of not having a female/male role model at home. | 0.390 | |||||

| (47) It will be easy to find health professionals who do not discriminate LGBT families. | 0.801 | |||||

| (46) It will be easy to find a school, which accepts all family types. | 0.708 | |||||

| (48) It will be easy to teach our child how to deal with prejudice. | 0.587 | |||||

| (45) Because they are not expecting us to have a child, our parents will provide us less support in the education of our child. | 0.664 | |||||

| (41) After having a child, our family will support us as parents. | 0.616 | |||||

| (37) Spending more time with our families of origin after being parents will improve our relationship. | 0.558 | |||||

| (33) My partner will accept the tips that my parents will give about childcare. | 0.521 | |||||

| (31) It will be easier to raise a child if we have our parents’ support. | 0.518 | |||||

| Subscale | Cronbach’s Alphas (α) | Cronbach’s Alphas (α) after Removing Item * |

|---|---|---|

| Coparenting Support | 0.900 | |

| Coparenting Undermining | 0.745 | |

| Coparenting Disagreement | 0.657 | 0.687 |

| Conflict with Families of Origin | 0.709 | |

| Institutional Support | 0.714 | 0.795 |

| Support from Families of Origin | 0.589 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leal, D.; Gato, J.; Coimbra, S.; Tasker, F.; Tornello, S. The Prospective Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (PCRS) for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual People: Preliminary Validation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106345

Leal D, Gato J, Coimbra S, Tasker F, Tornello S. The Prospective Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (PCRS) for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual People: Preliminary Validation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106345

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeal, Daniela, Jorge Gato, Susana Coimbra, Fiona Tasker, and Samantha Tornello. 2022. "The Prospective Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (PCRS) for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual People: Preliminary Validation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106345

APA StyleLeal, D., Gato, J., Coimbra, S., Tasker, F., & Tornello, S. (2022). The Prospective Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (PCRS) for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual People: Preliminary Validation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106345