Determinants of Differences in Health Service Utilization between Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Older Rural Residents: Evidence from a Decomposition Approach

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

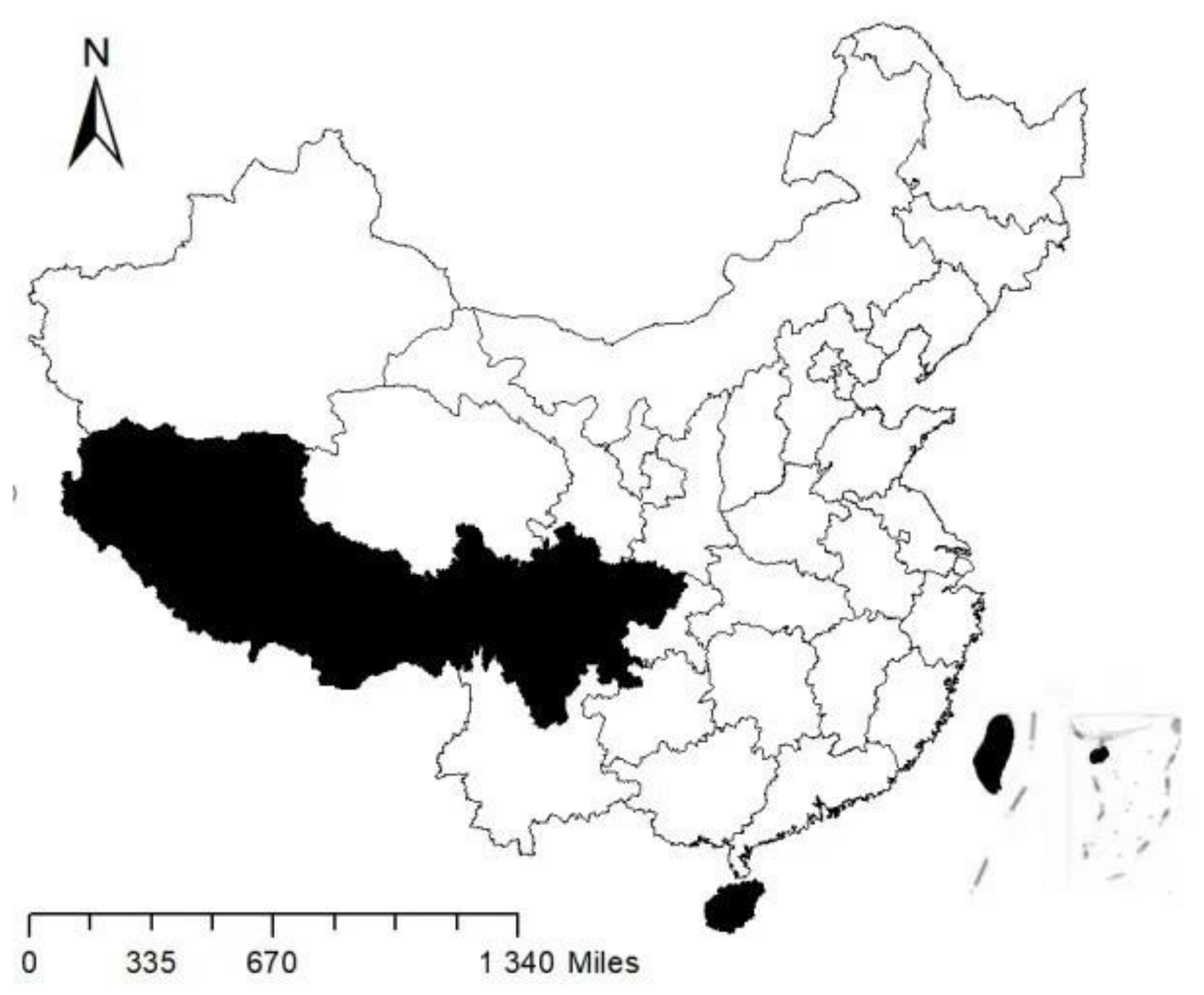

2.1. Data

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Measurements

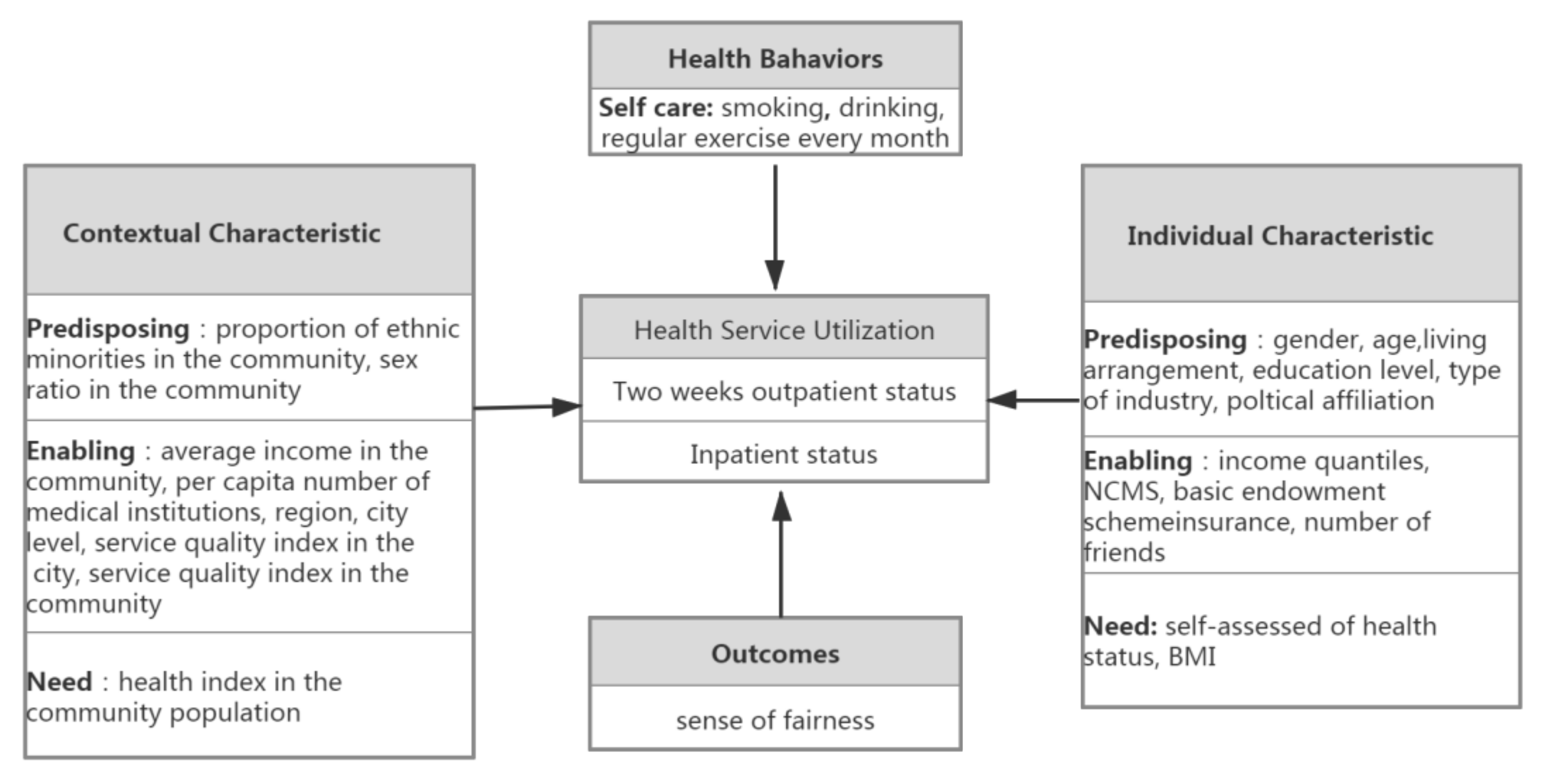

2.4. Predictor

2.5. Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM)

2.6. Fairlie Decomposition

3. Result

3.1. Matching Performance

3.2. Logit Regression Analysis

3.3. Fairlie’s Decomposition of Differences in Health Service Utilization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLDS | China Labor-Force Dynamic Survey |

| CEM | coarsened exact matching method |

| Hukou | Chinese household registration system |

| NCMS | New cooperative medical scheme |

| SAH | self-assessed of health status |

| 95%CI | 95% Coefficient Interval |

References

- The National Bureau of Statistics. Survey Report on Rural-to-Urban Migrants. 2020. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202004/t20200430_1742724.html (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Wang, T.T.; Dds, M.; Neeraj, M.A. The Graying of America: Considerations and Training Needs for Geriatric Patient Care-ScienceDirect. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 1741–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Nawaz, R. Health Disparity between the Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Their Rural Counterparts in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. Decomposing Differences of Health Service Utilization among Chinese Rural Migrant Workers with New Cooperative Medical Scheme: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Duan, C.; Zhu, X. Effect of Social Support on Psychological Well-being in Elder Rural-urban Migrants. Popul. J. 2016, 4, 93–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Min, D.; Ma, W. Utilization of outpatient service and influential factors of expenditure of middle-aged and elderly migrant workers in China. J. Peking Univ. 2015, 47, 464–468. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Taylor, J.E. Migration Incentives, Migration Types: The Role of Relative Deprivation. Econ. J. 1991, 101, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rubio, D.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. Inequalities in the use of health services between immigrants and the native population in Spain: What is driving the differences? Eur. J. Health Econ. 2011, 12, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, F.B.; Zick, C.D.; Simonsen, S.E.; Mukundente, V.; Davis, F.A.; Digre, K. Assessing the Likelihood of Having a Regular Health Care Provider among African American and African Immigrant Women. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. Difference in utilization of basic public health service between registered and migrant population and its related factors in China. Chin. J. Public Health 2018, 34, 781–785. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Hu, R.; Dong, Z.; Hao, Y. Comparing the needs and utilization of health services between urban residents and rural-to-urban migrants in China from 2012 to 2016. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puszczalowska-Lizis, E.; Koziol, K.; Omorczyk, J. Perception of footwear comfort and its relationship with the foot structure among youngest-old women and men. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, G.; Subramanian, S.V.; Daniel, V.; Danny, D. Internal migration, area effects and health: Does where you move to impact upon your health? Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 136–137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, R.; Rice, T.H.; Kominski, G. Changing the U. S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services, Policy, and Management. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 286, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, L.; Awe, W. Health Services Utilization Model. In Handbook of Health Behavior Research; Gochman, D., Ed.; Determinants of Health Behavior: Personal and Social; Plenum Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Bock, J.O.; König, H.H. Which factors affect health care use among older Germans? Results of the German ageing survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.; Le, Y. Anderson Health Service Utilization Behavior Model: Interpretation and Operationalization of Indicator System. Chin. Health Econ. 2018, 37, 5–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Andson’s behavioral model of Health Service Utilization and its application. J. Nanjing Med. Univ. 2018, 18, 11–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, L. Local Government Finance expends, official appointment and investment synchronism. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 3–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Si, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Unequal distribution of health human resource in mainland China: What are the determinants from a comprehensive perspective? Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Provisions on the Statistical Division of Urban and Rural Areas. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/5rp/html/append7.htm (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Yip, W.; Hsiao, W.C. The Chinese Health System at A Crossroads. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Health Statistics and Information. Research on National Health Services: An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in 2003; Xie He Medical University Press: Beijing, China, 2004; ISBN 81072-593-9.

- Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China; Peking Union Medical College Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 77–78. ISBN 9787567904941.

- Gelberg, L.; Andersen, R.M.; Leake, B.D. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to Medical Care Use and Outcomes for Homeless People. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 34, 1273–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, J.A.; Coberley, C.; Pope, J.E.; Wells, A. Extending coarsened exact matching to multiple cohorts: An application to longitudinal well-being program evaluation within an employer population. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Method 2015, 15, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.E.; Imai, K.; Stuart, K.E.A. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal. 2007, 15, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iacus, S.M.; King, G.; Porro, G. Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Anal. 2012, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacus, S.M.; King, G.; Porro, G. Multivariate Matching Methods That Are Monotonic Imbalance Bounding. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gotsadze, G.; Murphy, A.; Shengelia, N.; Zoidze, A. Healthcare utilization and expenditures for chronic and acute conditions in Georgia: Does benefit package design matter? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hametner, C.; Kellert, L.; Ringleb, P.A. Impact of sex in stroke thrombolysis: A coarsened exact matching study. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackwell, M.; Iacus, S.; King, G. cem: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. Stata J. 2009, 9, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Morakinyo, O.M.; Balogun, F.M. Sex inequality in under-five deaths and associated factors in low and middle-income countries: A Fairlie decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieu, S.; Klara, J. Disentangling the rural-urban immunization coverage disparity in The Gambia: A Fairlie decomposition. Vaccine 2020, 37, 3088–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Internal migration and health: Re-examining the healthy migrant phenomenon in china. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Rural-urban migration and health: Evidence from longitudinal data in Indonesia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le Kim, A.T.; Pham, L.T.; Vu, L.H.; Schelling, E. Health services for reproductive tract infections among female migrant workers in industrial zones in Ha Noi, Viet Nam: An in-depth assessment. Reprod. Health 2012, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohammadi Bidhandi, H.; Patrick, J.; Noghani, P.; Varshoei, P. Capacity planning for a network of community health services. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 275, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.D.; Cuthel, A.M.; Grudzen, C.R. Access to Home and Community Health Services for Older Adults With Serious, Life-Limiting Illness: A Study Protocol. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2020, 38, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pei, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wu, B. Outpatient Visits among Older Adults Living Alone in China: Does Health Insurance and City of Residence Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, D. Health inequality among rural elder residents in Shaanxi province. Chin. J. Public Health 2022, 38, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crettaz, E. Alleviating Working Poverty in Postindustrial Economies; Université de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_E6B51B41D085.P001/REF.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Liu, J. Working Poor in Mainland China: Concept and Life Trajectory of Its Main Working Groups. J. US-China Public Adm. 2017, 14, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, C.; Espelt, A.; Rodriguez-Sanz, M.; Burström, B.; Muntaner, C.; Pasarín, M.I.; Benach, J.; Marinacci, C.; Roskam, A.J.; Schaap, M.; et al. Analyzing differences in the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in self-perceived health by countries of different political tradition in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 2009, 39, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.; Zeng, J.; Zeng, Z. What limits the utilization of health services among china labor force? analysis of inequalities in demographic, socio-economic and health status. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Before Matching N (%) Mean (SD) | After Matching N (%) Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers | Older Rural Dwellers | p-Value * | Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers | Older Rural Dwellers | p-Value # | |

| Two weeks Outpatient | 57 (5.99) | 240 (8.93) | <0.01 | 48 (5.59) | 118 (8.11) | <0.01 |

| Inpatient | 75 (7.88) | 284 (10.61) | <0.05 | 65 (7.57) | 131 (9.07) | <0.05 |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | <0.001 | 0.743 | ||||

| Men † | 666 (69.96) | 1448 (54.11) | 617 (71.83) | 822 (56.49) | ||

| Women | 286 (30.04) | 1228 (45.89) | 242 (28.17) | 633 (43.51) | ||

| Age | <0.001 | 0.892 | ||||

| 50–54 † | 506 (53.15) | 848 (31.69) | 469 (54.6) | 551 (37.87) | ||

| 55–60 | 198 (20.8) | 511 (19.1) | 164 (19.09) | 210 (14.43) | ||

| 61–65 | 248 (26.05) | 1317 (49.22) | 226 (26.31) | 694 (47.7) | ||

| Living arrangement | 0.151 | 0.807 | ||||

| Live without spouse † | 45 (4.73) | 160 (5.98) | 15 (1.75) | 27 (1.86) | ||

| Live with spouse | 907 (95.27) | 2516 (94.02) | 844 (98.25) | 1428 (98.14) | ||

| Educational attainment | <0.05 | 0.771 | ||||

| Below primary school † | 420 (44.12) | 1750 (65.4) | 391 (45.52) | 971 (66.74) | ||

| Primary school | 365 (38.34) | 731 (27.32) | 333 (38.77) | 395 (27.15) | ||

| Middle school and above | 167 (17.54) | 195 (7.29) | 135 (15.72) | 89 (6.12) | ||

| Political affiliation | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Party members † | 90 (9.45) | 139 (5.19) | 81 (9.43) | 75 (5.15) | ||

| The masses | 862 (90.55) | 2537 (94.81) | 778 (90.57) | 1380 (94.85) | ||

| Type of industry | ||||||

| Manufacturing and construction † | 406 (44.76) | - | 413 (48.08) | 48.08 | ||

| Wholesale, retail trade, and catering | 146 (16.1) | - | 128 (14.9) | 14.9 | ||

| Transportation and other non-agricultural sectors | 355 (39.14) | - | 318 (37.02) | 37.02 | ||

| Farming | - | 2676 (100) | - | 1455 (100) | ||

| Place of work | ||||||

| Local † | 458 (48.26) | - | 650 (75.67) | 75.67 | ||

| Out-of-town | 491 (51.74) | - | 209 (24.33) | 24.33 | ||

| Working hours | ||||||

| Moderate labor † | 724 (76.05) | - | 408 (47.5) | 47.5 | ||

| Excessive labor | 228 (23.95) | - | 451 (52.5) | 52.5 | ||

| NCMS | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes † | 869 (91.28) | 2501 (93.46) | 781 (90.92) | 1372 (94.3) | ||

| None | 83 (8.72) | 175 (6.54) | 78 (9.08) | 83 (5.7) | ||

| Basic endowment scheme | < 0.05 | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes † | 878 (92.23) | 2540 (94.92) | 794 (92.43) | 1390 (95.53) | ||

| None | 74 (7.77) | 136 (5.08) | 65 (7.57) | 65 (4.47) | ||

| Income quantiles | 0.326 | 0.897 | ||||

| Poorest † | 20 | 2.1 | 48 (22.33) | 226 (20.79) | ||

| Poorer | 40 | 4.2 | 42 (19.53) | 214 (19.69) | ||

| Middle | 154 | 16.18 | 50 (23.26) | 224 (20.61) | ||

| Richer | 333 | 34.98 | 30 (13.95) | 236 (21.71) | ||

| Richest | 405 | 42.54 | 45 (20.93) | 187 (17.20) | ||

| SAH | <0.001 | 0.833 | ||||

| Good † | 583 (61.24) | 1159 (43.31) | 538 (62.63) | 709 (48.73) | ||

| Fair | 276 (28.99) | 821 (30.68) | 246 (28.64) | 461 (31.68) | ||

| Poor | 93 (9.77) | 696 (26.01) | 75 (8.73) | 285 (19.59) | ||

| BMI | <0.001 | 0.916 | ||||

| Underweight † | 42 (4.41) | 282 (10.54) | 22 (2.56) | 57 (3.92) | ||

| Ideal | 535 (56.2) | 1575 (58.86) | 501 (58.32) | 948 (65.15) | ||

| Overweight | 375 (39.39) | 819 (30.61) | 336 (39.12) | 450 (30.93) | ||

| Number of friends | 0.078 | 0.398 | ||||

| ≤5 † | 543 (57.04) | 1628 (60.84) | 491 (57.16) | 858 (58.97) | ||

| 6~10 | 226 (23.74) | 551 (20.59) | 201 (23.4) | 312 (21.44) | ||

| ≥11 | 183 (19.22) | 497 (18.57) | 167 (19.44) | 285 (19.59) | ||

| Health behavior | ||||||

| Smoking | <0.001 | <0.05 | ||||

| Yes † | 331 (34.77) | 631 (23.58) | 396 (46.1) | 349 (23.99) | ||

| No | 621 (65.23) | 2045 (76.42) | 463 (53.9) | 1106 (76.01) | ||

| Drinking | <0.001 | 0.099 | ||||

| Yes † | 320 (33.61) | 697 (26.05) | 288 (33.53) | 394 (27.08) | ||

| No | 632 (66.39) | 1979 (73.95) | 571 (66.47) | 1061 (72.92) | ||

| Regular exercise every month | <0.001 | <0.05 | ||||

| Yes † | 232 (24.37) | 510 (19.06) | 202 (23.52) | 292 (20.07) | ||

| No | 720 (75.63) | 2166 (80.94) | 657 (76.48) | 1163 (79.93) | ||

| Health outcome | ||||||

| Sense of fairness | 0.246 | 0.152 | ||||

| Unhappy † | 58 (6.09) | 204 (7.62) | 49 (5.7) | 87 (5.98) | ||

| Fair | 283 (29.73) | 809 (30.23) | 248 (28.87) | 430 (29.55) | ||

| Happy | 611 (64.18) | 1663 (62.14) | 562 (65.42) | 938 (64.47) | ||

| Contextual characteristic | ||||||

| Proportion of ethnic minorities (%) | 3.99 (15.35) | 10.61 (25.37) | <0.01 | 4.17 (15.95) | 8.34 (19.15) | <0.05 |

| Sex ratio in the community (%) | 1.04 (1.78) | 1.62 (6.08) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.54) | 1.91 (8.03) | <0.05 |

| Number of health facilities per capita in the community | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | <0.05 |

| Service quality index of the community | 0.66 (1.31) | 0.49 (1.31) | <0.001 | −0.01 (0.09) | −0.06 (0.01) | <0.01 |

| Service quality index of the city | 0.80 (1.67) | 0.57 (1.12) | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.81) | 0.08 (0.03) | <0.01 |

| Health index of the community population | 0.69 (0.64) | 1.02 (0.61) | <0.01 | 0.01 (0.21) | 0.01 (0.31) | <0.01 |

| Region | <0.001 | <0.05 | ||||

| East † | 55 (21.24) | 1071 (40.02) | 612 (71.25) | 594 (40.82) | ||

| Middle | 60 (23.17) | 851 (31.8) | 147 (17.11) | 488 (33.54) | ||

| West | 144 (55.6) | 754 (28.18) | 100 (11.64) | 373 (25.64) | ||

| City level | <0.01 | 0.08 | ||||

| Sub-provincial city and above † | 71 (16.82) | 497 (18.57) | 123 (14.32) | 307 (21.1) | ||

| Below sub-provincial city | 108 (25.59) | 2179 (81.43) | 736 (85.68) | 1148 (78.9) | ||

| L1 | 0.6372 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Variable | Two Weeks Outpatient | Inpatient | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers | Older Rural Dwellers | Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers | Older Rural Dwellers | |||||

| Individual characteristics | ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men † | ||||||||

| Women | −0.2605 | 0.4764 | 0.1698 | 0.2641 | 0.4459 | 0.4378 | −0.1142 | 0.2441 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 50–54 † | ||||||||

| 55–60 | −1.3506 * | 0.679 | −0.4980 | 0.379 | 0.2396 | 0.4238 | 0.0254 | 0.3387 |

| 61–65 | −0.3351 | 0.4718 | −0.2933 | 0.2662 | 0.4382 | 0.3961 | 0.2193 | 0.2463 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||||

| Live with spouse † | ||||||||

| Live without spouse | 0.3737 | 1.3539 | 0.1723 | 0.7797 | −0.8918 | 0.82 | 0.4313 | 0.773 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Below primary school † | ||||||||

| Primary school | 0.3199 | 0.4144 | 0.1719 | 0.2829 | 0.3042 | 0.3642 | −0.5742 * | 0.2851 |

| Middle school and above | 0.2252 | 0.6897 | −0.2361 | 0.7659 | −0.0760 | 0.529 | −1.3347 * | 0.7577 |

| Political affiliation | ||||||||

| Party members † | ||||||||

| The masses | 0.3737 | 1.3539 | 1.4445 | 1.0397 | 0.3147 | 0.5688 | 0.2126 | 0.5518 |

| Type of industry | ||||||||

| Manufacturing and construction † | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Wholesale, retail trade and catering | 0.2284 | 0.4881 | - | - | 0.0088 | 0.4325 | - | - |

| Transportation and other non-agricultural sectors | −0.4293 | 0.4437 | - | - | 0.0903 | 0.3556 | - | - |

| Farming | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Place of work | ||||||||

| Local † | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Out-of-town | −0.4509 | 0.4723 | - | - | −0.9231 ** | 0.4394 | - | - |

| Working hours | ||||||||

| Moderate labor † | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Excessive labor | 0.058 | 0.3842 | - | - | 0.5263 | 0.3224 | - | - |

| Medical scheme | ||||||||

| Yes † | ||||||||

| None | 0.9745 | 0.9632 | −0.4634 | 0.743 | 0.0567 | 0.8505 | −0.3626 | 0.6252 |

| NCMS | ||||||||

| Yes † | ||||||||

| None | −0.2336 | 1.0771 | −0.8543 | 0.9036 | −0.6618 | 0.976 | 0.034 | 0.6824 |

| Income quantiles | ||||||||

| Poorest † | ||||||||

| Poorer | −0.1935 | 0.5214 | −0.2197 * | 0.3057 | 0.0848 | 0.4711 | −0.1497 | 0.2972 |

| Middle | −0.5663 | 0.5753 | −0.0829 * | 0.3082 | −0.0343 | 0.5107 | −0.1875 | 0.3074 |

| Richer | 0.1037 | 0.5903 | −0.4252 | 0.3538 | 0.723 | 0.5117 | 0.1213 | 0.3148 |

| Richest | −1.3272 | 0.7641 | −0.5246 | 0.4252 | 1.0054 | 0.5033 | 0.1817 | 0.3524 |

| SAH | ||||||||

| Good † | ||||||||

| Fair | 0.5303 | 0.4561 | 0.9238 *** | 0.3037 | 0.7800 ** | 0.3511 | 0.8786 *** | 0.2685 |

| Poor | 2.5872 *** | 0.477 | 2.0299 *** | 0.2974 | 2.3718 *** | 0.4031 | 1.7987 *** | 0.2707 |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Underweight † | ||||||||

| Ideal | 0.3076 | 0.3769 | −0.7318 ** | 0.4083 | −0.8318 | 0.6449 | 0.5406 | 0.5051 |

| Overweight | 0.3994 | 1.2811 | −0.7271 | 0.4433 | −1.5398 | 0.6774 | 0.2122 | 0.5372 |

| Number of friends | ||||||||

| ≤5 † | ||||||||

| 6~10 | −0.5572 | 0.5049 | 0.33 | 0.2504 | 0.1084 | 0.3899 | 0.7072 ** | 0.2305 |

| ≥11 | 0.2666 | 0.5337 | −0.2957 | 0.3089 | 0.4095 | 0.3968 | 0.2182 | 0.2659 |

| Health behavior | ||||||||

| Smoking | <0.001 | <0.05 | ||||||

| Yes † | ||||||||

| No | 0.1269 | 0.4569 | 0.5024 | 0.3139 | −0.0830 | 0.3715 | 0.2018 | 0.275 |

| Drinking | ||||||||

| Yes † | ||||||||

| No | 0.9937 | 0.5225 | 0.2418 | 0.2987 | −0.4316 | 0.367 | 0.1285 | 0.2569 |

| Regular exercise every month | ||||||||

| Yes † | ||||||||

| No | −0.6749 | 0.3976 | −0.0720 | 0.2891 | −0.8280 ** | 0.326 | 0.0099 | 0.2668 |

| Health outcome | ||||||||

| Sense of fairness | ||||||||

| Unhappy † | ||||||||

| Fair | 0.2501 | 0.6492 | −0.9945 * | 0.3519 | −1.2225 ** | 0.5714 | −0.6119 | 0.3633 |

| Happy | −0.8565 | 0.6635 | −0.7262 ** | 0.3299 | −0.7139 | 0.5209 | −0.3945 | 0.3457 |

| Contextual characteristic | ||||||||

| Proportion of ethnic minorities | −0.0113 | 0.0134 | 0.0016 | 0.0041 | 0.01 | 0.0089 | 0.0032 | 0.0037 |

| Sex ratio in the community | −1.0148 | 0.7023 | −0.0088 | 0.0269 | −0.0876 | 0.2968 | 0.0192 | 0.0099 |

| Number of health facilities per capita in the community | −158.2989 | 235.357 | 11.246 | 74.8736 | −20.7497 | 178.8096 | 16.2103 | 66.6137 |

| Service quality index of the community | 0.3742 | 0.3038 | −0.3039 | 0.2366 | 0.1196 | 0.2612 | −0.0969 * | 0.2069 |

| Service quality index of the city | 0.3298 | 0.2225 | −0.0079 | 0.1764 | 0.1004 | 0.1946 | −0.0895 | 0.1746 |

| Health index of the community population | −0.3254 | 0.4373 | −0.2828 | 0.1864 | 0.0713 | 0.2406 | −0.1125 | 0.1328 |

| Region | ||||||||

| East † | ||||||||

| Middle | 0.3376 | 0.557 | −0.2886 | 0.2875 | 0.4398 | 0.4448 | −0.4139 | 0.2719 |

| West | 0.6087 | 0.5788 | 0.0615 | 0.2638 | 0.2092 | 0.5073 | 0.1955 | 0.2379 |

| City level | ||||||||

| Sub-provincial city and above † | ||||||||

| Below sub-provincial city | 2.2806 * | 1.165 | 0.0275 | 0.2803 | 0.0476 | 0.4482 | 0.0572 | 0.2565 |

| Terms of Decomposition | Two Weeks Outpatient | Inpatient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total gap (%) | −0.0082 | −0.0106 | ||||

| Explained (%) | 17.98% | 71.88% | ||||

| Explained | ||||||

| Variable | Contribution (%) | 95%CI | Contribution (%) | 95%CI | ||

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Age | −4.44 | −0.0028 | 0.0035 | −0.30 | −0.0014 | 0.0015 |

| Gender | 5.27 | −0.0032 | 0.0023 | 27.91 | −0.0081 | 0.0021 |

| Living arrangement | −0.95 | −0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.57 | −0.0007 | 0.0006 |

| Educational level | 0.16 | −0.0014 | 0.0014 | 39.20 | −0.0084 | 0.0000 |

| Income quantiles | −25.26 | −0.0019 | 0.0060 | 49.57 * | −0.0103 | −0.0003 |

| NCMS | 14.61 | −0.0071 | 0.0047 | 8.29 | −0.0076 | 0.0059 |

| Basic endowment scheme | −5.31 | −0.0035 | 0.0044 | 2.84 | −0.0045 | 0.0039 |

| Political affiliation | −9.86 | −0.0006 | 0.0023 | 7.14 | −0.0029 | 0.0014 |

| Number of friends | 7.77 | −0.0025 | 0.0012 | 7.80 | −0.0028 | 0.0012 |

| SAH | 0.92 | −0.0045 | 0.0043 | 80.91 *** | −0.0139 | −0.0033 |

| BMI | −5.35 | −0.0015 | 0.0023 | −16.12 | −0.0007 | 0.0042 |

| Health behavior | ||||||

| Smoking | 1.76 | −0.0024 | 0.0021 | −17.59 | −0.0016 | 0.0054 |

| Drinking | −2.41 | −0.0016 | 0.0020 | 0.27 | −0.0013 | 0.0012 |

| Regular exercise every month | 7.47 | −0.0030 | 0.0018 | −3.15 | −0.0013 | 0.0020 |

| Health outcome | ||||||

| Sense of fairness | −0.63 | −0.0017 | 0.0018 | 6.31 | −0.0038 | 0.0024 |

| Contextual characteristic | ||||||

| Proportion of ethnic minorities | −0.49 | −0.0016 | 0.0017 | 2.36 | −0.0014 | 0.0009 |

| Sex ratio in the community | 2.99 | −0.0016 | 0.0011 | −102.29 *** | 0.0065 | 0.0152 |

| Number of health facilities per capita in the community | 3.62 | −0.0028 | 0.0022 | 4.45 | −0.0027 | 0.0018 |

| Service quality index of the community | 30.10 | −0.0093 | 0.0043 | −6.05 | −0.0043 | 0.0056 |

| Service quality index of the city | 18.20 | −0.0074 | 0.0044 | −1.80 | −0.0074 | 0.0078 |

| Health index of the community population | 30.56 | −0.0070 | 0.0020 | −7.78 | −0.0034 | 0.0051 |

| Region | −50.68 | −0.0045 | 0.0128 | −9.46 | −0.0083 | 0.0103 |

| City level | −4.88 | −0.0018 | 0.0026 | 2.93 | −0.0016 | 0.0010 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Yang, J.; Zhai, S.; Li, D. Determinants of Differences in Health Service Utilization between Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Older Rural Residents: Evidence from a Decomposition Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106245

Li L, Yang J, Zhai S, Li D. Determinants of Differences in Health Service Utilization between Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Older Rural Residents: Evidence from a Decomposition Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106245

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Li, Jinjuan Yang, Shaoguo Zhai, and Dan Li. 2022. "Determinants of Differences in Health Service Utilization between Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Older Rural Residents: Evidence from a Decomposition Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106245

APA StyleLi, L., Yang, J., Zhai, S., & Li, D. (2022). Determinants of Differences in Health Service Utilization between Older Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers and Older Rural Residents: Evidence from a Decomposition Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6245. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106245