Abstract

People in need of care also require support within the framework of structured dental care in their different life situations. Nowadays, deteriorations in oral health tend to be noticed by chance, usually when complaints or pain are present. Information on dental care is also lost when life situations change. An older person may rely on family members having oral health skills. This competence is often not available, and a lot of oral health is lost. When someone, e.g., a dentist, physician, caregiver, or family member notices a dental care gap, a structured transition to ensure oral health should be established. The dental gap can be detected by, e.g., the occurrence of bad breath in a conversation with the relatives, as well as in the absence of previously regular sessions with the dental hygienist. The aim of the article is to present a model for a structured geriatric oral health care transition. Due to non-existing literature on this topic, a literature review was not possible. Therefore, a geriatric oral health care transition model (GOHCT) on the basis of the experiences and opinions of an expert panel was developed. The GOHCT model on the one hand creates the political, economic, and legal conditions for a transition process as a basis in a population-relevant approach within the framework of a transition arena with the representatives of various organizations. On the other hand, the tasks in the patient-centered approach of the transition stakeholders, e.g., patient, dentist, caregivers and relatives, and the transition manager in the transition process and the subsequent quality assurance are shown.

1. Introduction

The increasing proportion of older people in the total population, the success of dental prevention programmes resulting in the retention of natural teeth until old age, and the heterogeneity of seniors, both in health and functionality as well as in financial and social terms, pose challenges to health, financial, social, and housing systems. Older adults with multiple chronic conditions and deficits in their oral health, often have deficits in activities of daily living and social barriers that make it difficult for them to manage their health care. They face many challenges. Events in the lives of seniors, such as a fall, can bring small but also massive changes in the care of the old and oldest old. These changes can have different dimensions—there are impacts on health, housing, social caregiving, and ultimately finances. For those affected, these events represent transitions that bring about profound and therefore also significant changes for the person and his or her environment. To manage the changes well and in a targeted manner for everyone involved, it is helpful and sensible to structure the transitions from one system to another. Transitions (from Latin: transitio) include the passage of a child’s entry into adolescence, from adolescence to adulthood, from partnership to parenthood, entry into the workforce, the youngest child leaving the household, retirement, and the end of a marriage through divorce or death. All these live events are well-known and scientifically monitored, as in, e.g., [1,2]. More specifically, a transition may involve: Restructuring, reorganization, sometimes a departure from the familiar, and occasionally a temporary assumption of new responsibilities to resolve entrenched situations.

In Germany, there is a mandatory statutory health insurance, which covers almost all German nationals and residents. Only people with a high income and a few other exceptions may be exempted. The scope of services is the same for all adult members, but there are some dental care paths that are separately funded. These include dental services for people with care needs. However, these benefits are limited to dental services only and currently do not include financial assistance for care to support interdisciplinary collaboration. Finding effective strategies to improve oral health care transitions and outcomes for this population is critical.

1.1. Epidemiology, General Aspects, and Oral Health in Older People

Demographic analyses report an increasing number of old and very old people in Germany [3] and societies worldwide.

More and more older people retain their own teeth into old age. Especially in Germany, this means that a decrease in the number of missing teeth can be observed in seniors aged 65–74 years [4,5,6] and in 75- to 100-year-olds [7]. At the same time, 44.3% present severe periodontal disease affecting the remaining teeth [7]. In addition, more than 35% of people in this age group are treated with removable dentures that require high levels of care and attention [6]. Nevertheless, with the increase in age and associated multimorbidity and frailty, the utilization of dental services by patients is declining sharply [8,9].

Parallel to the increasing number of old and very old people, the number of people in need of care is also rising sharply. In 2019, around 4.13 million people in Germany needed care as defined by the new care level definition of the German Long-Term Care Insurance Act [10]. Need for care affects all age groups, although the care rate is significantly higher among the very old [11]. 80% of those in need of care were aged 65 or older, and more than one-third (34%) were aged 85 or older. The proportion of people in need of long-term care in the population aged 90 and older was 76% [12].

There are numerous reports in the literature describing a dental care gap. However, these studies are often limited to residents of nursing facilities with care needs and their specific conditions, e.g., dementia [13,14]. In Germany, there is a population-representative study (Fifth German Oral Health Study, DMS V), which, in the case of 85–100-year-olds, included people with care needs regardless of their place of residence [15,16].

1.2. Objective of the Present Work

In senior dentistry, as in geriatrics, there are many changes in life where a structured transition would benefit oral and overall health. To the authors’ knowledge, structured transitions have not been described in dentistry yet. It is necessary for those involved in the care system of the person in need of care to communicate with each other, define needs, and agree on goals in the best interest of the patient. The aim of this paper is to describe a gerostomatological geriatric oral health care transition (GOHCT) model, within which all transitioners benefit from an attentive and structured transition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

In a first step, a selective literature search based on the PICO system criteria [17] was done to identify aspects of transitions or transition processes in dentistry. Since no literature was found on the topic, in a second step, the authors formed an expert panel to develop, describe and specify the thesis of a geriatric oral health care transition model on the basis of their observations, challenges, opinions, and experiences in the field of gerodontology. The expert panel consisted of the authors with long-term, university-based, clinical and scientific experience, or long-term practical experience in the field of gerodontology. Two of five experts experience two very differently structured healthcare systems regarding dental care and four of five members of the expert panel are certified specialists of the German Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für AlterszahnMedizin, DGAZ) for the field of gerodontology.

2.2. Transition Models in General

Structured transition management regulates transitions from an initial situation to a new and beneficial situation. A transition model describes the management of the transition not only as relating to the competence of the geriatric patient but deals with the interactions of all transition participants (e.g., relatives, legal guardians, physicians, caregivers) and therefore speaks of the competence of the social system. In medicine, there are various transition models, where, for example, an epidemiological transition in the form of a shift in the recorded causes of death from infectious diseases to other morbid conditions is described and discussed [18]. However, this does not consider one patient, but rather takes a population-representative approach. There are model calculations that were, for example, already made in the early 1980s [19], and which show that there are demographic transitions that must be considered in the course of population development [20,21].

The results of numerous studies demonstrate, in both medicine and dentistry, that inadequate medical [22,23,24] and dental care for older adults often lead to devastating human and economic consequences. Already in 1994, Schumacher and Meleis gave an overview of various transition models from the years of 1986–1992, all of which came from the field of nursing [25].

One model that has been tested as effective in meeting the needs of this heterogeneous population while reducing health care costs is the transitional care model (TCM) described in 2015 by Hirschman et al. The TCM is a caregiver-led intervention that targets seniors who face additional health risks when moving between different health care settings and physicians. The TCM describes evidence-based nine core components of the model and a care management approach [21]. The core components are screening, staffing, maintaining relationships, engaging patients and caregivers, assessing/managing risks, and symptoms, educating on and promoting self-management, collaborating, promoting continuity, and fostering coordination.

Three articles on transition in older people show in a summary of Morkisch et al. (2020) [26] that high-intensity multicomponent and multidisciplinary interventions are likely to be effective in reducing readmission rates in geriatric patients. Education and promotion of self-management, maintenance of relationships, and promotion of coordination also appear to play an important role in reducing readmission rates. It is shown that a structured transition in medical facilities leads to fewer readmissions to hospital [27].

In Germany, in medicine, the term transitional medicine has become established, e.g., for transitions from child-centered to adult-centered healthcare systems for young people with chronic diseases and disabilities [28,29]. Furthermore, health systems will experience transitional changes, e.g., in the use of digital instead of analog data processing [30]. A society for transitional medicine has also been formed, which aims to simplify transitions through standardization in paediatric and adolescent medicine for people with disabilities by providing training and structured continuing education [31].

2.3. Core Elements and Processes of a Transition Process

The transition is often divided into different phases and individually adapted to the situations with the knowledge as well as the experience from different fields. Transition competence includes the skills needed to cope with a crisis transition with gaps of any kind (e.g., treatments, care, etc.) and often requires interdisciplinary experience [32].

Transitions are frequently initiated by a transition manager. The transition manager may only temporarily be involved and may come from the direct external environment (e.g., the practice manager of the dentist or the dental assistant) of the geriatric patient. He or she conceptually develops and defines goals together with the geriatric patient and his or her internal (e.g., family, caregivers, etc.) and external environment (e.g., physicians, a dentist and his or her staff, etc.) to create a vision of the transition. The transition manager initiates the desired or necessary changes and accompanies the transitions until the previously agreed goals are achieved. The transition is monitored from start to finish and evaluated later for quality assurance [33].

The person affected by the transition, e.g., the geriatric patient or their representative (e.g., relatives, legal guardians, physicians, nurses) must cope with emotional upheavals, clarify their social affiliations again and again, adapt their identity in the transition to the contexts, and secure their existence as a fluid member of the organization through networking.

The transition arena is a platform in which previous experiences, opinions and expertise can be exchanged and problems analyzed to develop a common language as a basis to define the transition goals. The arena also serves to find a common way to address the problem and coordinate activities. Typically, 15–20 pioneers are involved, who should also be important actors in their fields [34].

The transition is complete when all participants in the transition system feel comfortable, the benefits of the transition are apparent to all participants, and the goals of the transition have been achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Transition Levels

Senior dentistry defines different phases of life and transition after retirement, which are not linked to age. The task of senior dentistry is to provide dental care for older people in their third (fit seniors), fourth (frail seniors), and fifth (seniors in need of care) phases of life. The aim is to always provide the best possible dental care with a high oral health-related quality of life. Senior dentistry therefore does not deal with old age at a specific point in time, but accompanies a continuously progressing process, the transition between the three phases, the aging or growing older of people. In this respect, senior dentistry as a discipline works together with representatives of the health sciences, nutritional sciences, nursing sciences, geriatrics, and medical ethics in multi- and interdisciplinary cooperation on scientific issues concerning oral and general health and thus also the quality of life of the old and very old. Geriatric dentists observe and accompany the transitions of their patients and could contribute intensively to delaying the change from one phase to the next as much as possible.

The health system has three levels, a macro-, meso-, and micro-level, involving different stakeholders. The macro- and meso-levels are decision-making platforms that have a population-representative influence. Laws are passed on the macro-level and then, translated by the statutory health insurance funds on the meso-level into implementing regulations for the user. Users on the micro-level in this case are the dentist and the patient who must comply with the regulations for dental care. The interactions of those involved in health care usually follow a top-down approach. Information, wishes, suggestions, as well as demands to those responsible in society, politics, and health care can, of course, also be passed on from the micro- and meso-level to the final decision-making level, the legal regulator on the macro-level.

The interaction of the three levels in case of the geriatric oral health care transition model was previously described by Nitschke et al. as the considerations on factors influencing the utilization behaviour [35]. The geriatric oral health care transition model has a population-presence perspective covering both the macro- and meso-levels and a patient-centered perspective on the micro-level.

The gerostomatologic transition is thus approached on two levels. The superordinate level with a transition from a population-representative gerostomatological point of view and the subordinate level with an adapted transition for a specific geriatric patient, oriented to his individual risks and personal needs. This also means that the generalized transition process from the population-representative gerostomatological point of view may not always be suitable for the individual situation of the geriatric patient and his supportive environment. Especially in old age, heterogeneity, shaped by the very different and very long life-courses, is one of the greatest challenges of the transition process.

3.2. Development of Terms of Transitional Dentistry

For a clearer understanding, the terms of transitional dentistry used in the geriatric oral health care transition model have been explained as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the basic terms of transitional dentistry on the patient-oriented, needs-adapted level.

3.3. The Geriatric Oral Health Care Transition (GOHCT) Model

At present it is rather left to chance and to the attention of the persons concerned to organize and implement the transition from independently organized dental treatment in the dental practice to dental care in different places in a structured way. The patient, as well as the dentist and his or her team, always belong to the group of those affected by gerostomatological transition. Other stakeholders may differ according to the specific phase of life. The gerostomatological transition could be initiated already at the beginning of the deterioration of oral health, with a focus on the control-oriented utilization of dental services and on the strengthening of a lifelong needs-adapted support with preventive and therapeutic approaches. Ensuring oral hygiene at home plays a crucial role here.

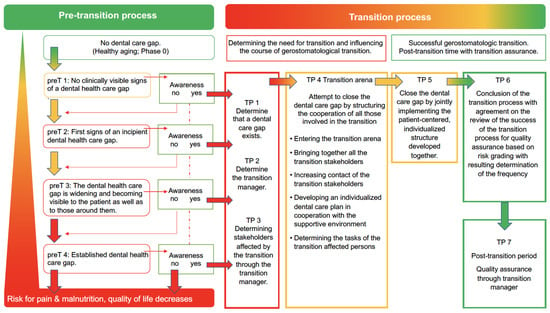

The patient-centered, needs-based geriatric oral health care transition model for everyday care consists of the pretransition process, the transition process, and a post-transition period (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Geriatric oral health care transition model with three superordinate stages of the pretransition process (preT 1–4 = stages of decreasing oral health literacy and increasing dental health care gap) and the four superordinate transition domains and their seven transition phases (TP).

Figure 1.

Visualization of the geriatric oral health care transition model. Pretransition process from no dental care gap in pretransition phase 0 towards the establishment of a dental care gap with pretransition phases preT 1–preT 4, as well as the transition process with transition phases TP 1 to 7.

The pretransition process consists of three superordinate stages with five pretransition phases. The need for dental geriatric transition is based on the occurrence and awareness of dental care gaps and is described in terms of pre-transition phases. Healthy aging (preT phase 0), as well as the onset (preT1 phase), as well as the progression of gerostomatologic pretransition (preT2 phase to preT4 phase) are described in the three superordinate stages from which a need for transition may arise. The extent of the dental care gap differs in each phase. If identified, it can be transitioned to the transition process at any phase point in the pretransition process. (Table 2, Figure 1) The transition process consists of four overarching transition areas with seven transition phases. Based on the outcome of the pretransition process, the transition process begins with the identification of the need and the initial preparations for working in the transition arena (TP 1–3). After a well-structured transition (TP 4, TP 5), it comes to a successful conclusion (TP 6). In the post-transition period, measures are taken to ensure the quality of the transition, which are agreed upon in the transition arena (TP 7) (Table 2, Figure 1). Non-dentally measurable changes should provide the decisive indication of a need for a transition process. If oral and dental signs, which can then certainly also be proven with instruments and indices, are perceptible and visible, the pretransition process is already too far advanced. The goal should be to already recognize other signs e.g., a changed appearance, changed utilization of dental services, changed medical diagnoses and medications, change of residence, loss of a partner, etc., and from these to elicit the need for transition at an early stage. Ideally the transition process should be initiated as early as possible—i.e., in a first phase after phase 0. (Table 2)

In order to develop a gerostomatologic transition at the risk-adapted individual patient level, the transition manager is required to identify the transition stakeholders and, with the expertise and knowledge of the patient, describe for all the transition phase in which the patient finds himself. The transition manager should facilitate clear and precise communication between all stakeholders and provide support in explaining professional technical terms of the various professional fields whenever needed. The existing role profiles should be reviewed in the transition group and, if necessary, established or adapted to the transition phase. In this context, the role of those affected to maintain the oral health of the geriatric patient should be clearly defined for each phase of the transition and stored in a quality management system with the corresponding standard operating procedures (SOP) in a simple language, i.e., understandable for all stakeholders. The creation of the overarching SOP can be a task of the population-based transition arena. The SOP must systematically describe the care claims, scope, frequencies, and tools of dental care. The SOP of the transition phases must be adapted, first, according to scientific knowledge and, second, in the patient-centered transition arena to the individual oral health risks of the geriatric patient. This individual adaptation and overall responsibility for the gerostomatologic transition process can only be performed by a dentist who can assess the individual oral health risk of his or her geriatric patient. However, it is important here that the responsibilities and the interfaces are clearly defined in the distribution of tasks (“Who is responsible for what”). Here, starting from the patient-oriented level, knowledge and experience from the population-oriented transition arena can be drawn upon when defining the process flows in the individual phases. A theoretically based strategy with generally valid SOPs, which derives solely from the knowledge of the population-oriented transition arena, cannot be sufficiently effective for the very heterogeneous patient risks in everyday life in individual cases. Implementing theoretical strategies alone instead of a risk- and need-adapted transition is not sufficiently effective. Therefore, a needs-adapted transition, which must also be adapted several times, will be the goal of senior dentists.

As part of the transition, there may be a change in the dental team that has been transitioning. The primary care dentist intentionally relinquishes responsibility for dental care to the future collaborating dentist when moving from the home to a nursing facility. The impetus for this could come from the outpatient care provider or family members in the transition arena.

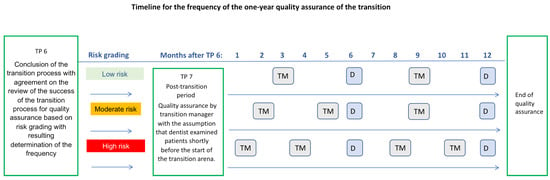

3.4. Risk Grading within the Framework of Quality Assurance

The transition process and outcome are subject to dynamic changes due to internal (within the transition-affected group) and external (outside the transition-affected group) influences. Internal influences may include, for example, a change of nurse or dentist as a transition-affected person, deterioration of the patient’s general medical condition, or changes in the concept of care (outpatient vs. inpatient). External influences on the transition process and its success can be sought, for example, at the macro- and meso-level in changes in legal requirements or the like. In the course of the transition, before a successful transition process is completed, it should be determined within the transition arena at what frequency the quality assurance of the transition is to be carried out. Risk grading is used for this purpose. It includes various risk factors (life situation, general medical risk, limitation of cognitive abilities, medication with oral consequences, limitation of manual oral hygiene ability, teeth, dentures) and a resulting specification of the risk. The grading is based on the risk factors (Table 3). According to the risk grading, the classification of the frequency of quality assurance measures can take place (Table 4, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Description of the risk factors (A), as well as classification of the frequency of quality assurance measures based on the risk grading (B).

Table 4.

Overview of gerostomatology transition tasks that require financial and time resources.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the frequency of transition quality assurance (TM—quality assurance by transition managers) and routine dental check-ups (D) within one year after successful completion of transition. Other appointments for dental treatment or care (e.g., professional dental cleanings) are not included here. The number of TM and D check-ups depends on the risk grading.

- If no risk factors or one risk factor are identified for the patient, the quality assurance of the transition results in a quality control check by the transition manager every 2–4 months after the last routine dental examination (at least twice a year).

- If at least two risk factors are identified, a medium risk is present. A quality control check should be performed every 4 months after completion of the transition.

- If more than two risk factors are present, there is a high risk. A quality control check should be performed every 3 months after completion of the transition.

When performing a gerostomatological transition, costs are also incurred, the financing of which would in turn have to be clarified by the health and long-term care insurance as part of the population-representative transition considerations (Table 4).

An explanatory case example of the geriatric oral health care transition model can be found in Supplementary Material File S1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Notes on the Population-Representative Oral Health Care Transition Model

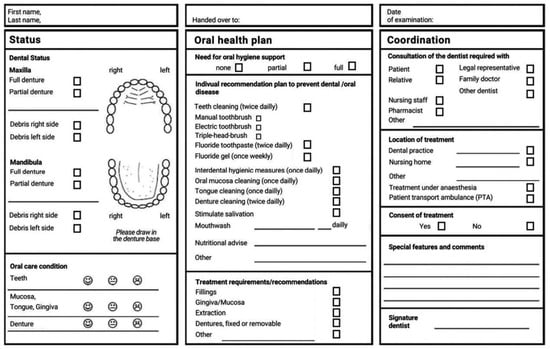

In Germany, in today’s oral health transition of an elderly person, the legislator at the macro-level and the statutory health insurance funds at the meso-level have already created some elements in oral health care that can be used by the dentists in the micro-level, such as the cooperation agreement between the long-term care facility and the cooperation dentist or oral health sheet (Figure 3) [36].

Figure 3.

Oral care nursing plan [36] developed for members of statutory health insurance and their carers or supporting persons as part of the cooperative agreement between dentists and nursing homes. The plan aims to improve communication regarding oral health and oral hygiene requirements with the nursing home staff and other caregivers.

The tasks within the transition arena are manifold. In a population-representative approach for example, transition expertise is required to develop a legal framework. The multidisciplinary composition of the transition actors in the interdisciplinary transition arena needs to be identified. The transition stakeholders in a population-representative approach include many different actors: representation of dentists from the scientific and practical field of activity, their team members, physicians, nursing professionals, patient representatives, representatives of relatives, representatives of the statutory health insurance funds, representatives of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists, representatives from the political bodies and the guardians’ organization.

In this transition arena, the need for a secure and sustainable GOHCT should be formulated and prepared for the meso-level for legal implementation. Generally valid SOPs should be formulated, which should then find their way into the patient-centered transition arena via the regulations implemented by the statutory health insurance funds. In the population-centered transition arena, the financial viability of GOHCT must also be discussed, as costs arise in the transition process in patient-centered everyday GOHCT. It is important to clarify who will bear the costs of training and the later use of the patient-oriented transition arena in everyday life, and who will later work in the transition arena beaing in mind the economic situation of the funders.

With the increasing shortage of personnel on the one hand and the increase of the older population as a proportion of the total population on the other, the availability of dental as well as nursing care services and health insurance must also be reviewed.

The goals set in the transition arena are then to be implemented by the participating bodies of the health insurers (meso-level) as well as in the political bodies (macro-level). It must be considered that there are political priorities (e.g., climate, education, health), which may also change due to changes in government. It also plays a role whether the health budget can provide sufficient funds to finance the transition (Table 5).

Table 5.

Requirements and needs for the transition in the population-representative approach.

4.2. Notes on the Individual, Patient-Adapted Oral Health Care Transition Model

At present, however, it is rather left to chance and the attention of those affected to organize and ensure in a structured way the transition from the usual dental treatment organized by the patient independently in the dental practice to dental care in different places. The group of people affected by the patient’s functional changes depends on the phase of life. The patient, as well as the dentist and his or her team, always belong to the group of gerostomatological transition-affected persons. Already at the beginning of the deterioration of oral health, the gerostomatological transition could start with the focus on the control-oriented utilization of dental services and on the strengthening of a lifelong needs-adapted support with preventive and therapeutic approaches. In this context, ensuring oral hygiene at home plays a crucial role. As the patient’s limitations progress, other persons become involved in the patient’s care or support. Individual agreements between the parties involved are necessary. As a rule, however, these arrangements do not take place in a structured manner with all those involved, so that there is often a loss of information in everyday life and the possibilities are not sufficiently explored in the patient’s best interests. The patient-centered, i.e., individual-needs-oriented geriatric oral health care transition model was developed from these observations in everyday dental care.

The patient-centered, needs-based geriatric oral health care transition model views the management of the transition from dental treatment to dental care not only as the responsibility of the dentist or the aging patient, but the interaction of all those involved in the support process (supportive environment). In the everyday geriatric oral health care transition model, the competence of the providing system is demanded in order not to let a care gap in dental care arise, or to close the care gaps that exist today.

Transition is therefore more than just the delivery of a senior in administrative terms from one treatment or care system and environment to another (outpatient versus inpatient, home versus care facility). It should take place in a sensitive and structurally regulated manner, especially in the vulnerable phase of old age. It should be individually oriented, considering the oral diagnosis, the functional resources or limitations, the dental functional capacity, the family context, and the social context.

Functionally impaired seniors often challenge both, the individual supportive environment (e.g., family members, legally appointed caregivers, nursing) as well as the medical care system to maintain health or manage oral disease events. The resulting health damage to the stomatognathic system affects the other systems, such as speech, food intake, and what is lost is often not recoverable in old age. The condition is then often irreversible, such as a missed opportunity for the adaptation to new dentures that should have occurred earlier. In a geriatric patient with severely reduced dental functional capacity, adaptation to new dentures is much more difficult, and often no longer possible. Gaps in dental care in old age should therefore be avoided as far as possible or counteracted at the earliest opportunity.

There is a special dental patient-oriented care need due to the otherwise occurring consequences of neglected oral and prosthetic hygiene and missed control-oriented dental utilization. Considerations and questions that form the basis for a framework for senior dentistry are attempted by the pillar image with the four main areas of senior dentistry. These are interdisciplinary teamwork, minimally invasive dentistry, oral functionality and patient-centered care in dentistry [37]. Each aged or very old person is unique and brings with them a wide range of genetic backgrounds and environmental factors, including social, cultural, economic, and cohort-specific life experiences that have influenced health beliefs and behaviors [38]. Tailored concepts are therefore required if dental care gaps are to be closed—irrespective of age or physical disability. For example, only 69.2% of Italian dentists (central Italy, Abruzzo region) treat people with disabilities. Out of them almost three quarters treat less than 10 patients with disabilities per year. Half of all dentists in this Italian study also refused to treat patients with cognitive impairment or a poor ability to collaborate during treatment. On the other side, half of all questioned people with disabilities or their caregivers reported a non-utilization of dental services [39].

The importance and necessity of a systematic transition, especially for multimorbid people with chronic diseases, has long been recognized in and outside dentistry [35]. As an example, in Germany, a dentist in private practice and therefore working on an outpatient basis cannot invoice his services for a patient in the setting of a hospital for acute geriatrics to the statutory health insurance due to the status of an inpatient stay.

Table 6 compares the requirements and needs for the transition to a patient-oriented, needs-adapted individual approach. (Table 6)

Table 6.

Requirements and needs for the transition in the patient-oriented, needs-adapted individual approach.

5. Conclusions

Gerostomatalogical transition is already taking place in isolated cases, although there are no clear structures at the two population- and patient-centered levels of care. The geriatric oral health care transition model proposed, requires both personnel-related and financial resources for implementation. This requires activities at all three levels of the health system to rebuild the existing structures for structured translation. Differences between seniors living at home and those receiving inpatient care must be resolved in the sense of a patient-adapted transition.

Until now, patients with care needs and patient-related risk factors have to compensate for the dental care gap with their financial resources to achieve an adequate oral health status. The dentist is currently not compensated for providing the infrastructure to provide gerostomatology transition for their patients and their families. Also, the training costs for the transition manager as well as the transition nurse and the additional costs for the intensive oral care provided by the nurse are not yet covered.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19106148/s1, File S1: Example of a geriatric oral health care transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.N.; writing—original draft preparation, I.N.; writing—review and editing, S.N., C.H., B.A.J.S. and J.J.; visualization, I.N. and J.J.; supervision, I.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gesellschaft für Transitionsmedizin e.V. Transition von der Pädiatrie in die Erwachsenenmedizin. S3-Leitlinie der. Gesellschaft für Transitionsmedizin. 2021. Available online: https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/186-001l_S3_Transition_Paediatrie_Erwachsenenmedizin_2021-04.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Odone, A.; Gianfredi, V.; Vigezzi, G.P.; Amerio, A.; Ardito, C.; d’Errico, A.; Stuckler, D.; Costa, G.; Italian Working Group on Retirement and Health. Does retirement trigger depressive symptoms? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung. Anteil der Altersgruppen unter 20 Jahren, ab 65 Jahre und ab 80 Jahre (1871–2060). 2021. Available online: https://www.bib.bund.de/DE/Fakten/Fakt/B15-Altersgruppen-Bevoelkerung-1871-Vorausberechnung.html (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Lenz, E. Prävalenzen Zu ausgewählten klinischen Variablen bei Senioren (65–74 Jahre): Zahnprothetischer Status bei den Senioren. In Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS III). Ergebnisse, Trends und Problemanalysen auf der Grundlage Bevölkerungsrepräsentativer Stichproben in Deutschland 1997; Deutscher Zahnärzteverlag DÄV: Köln, Germany, 1999; pp. 385–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kerschbaum, T. Zahnverlust und Prothetische Versorgung. In Vierte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS IV); Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2006; Volume 31, pp. 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, I.; Stark, H. Krankheits-und Versorgungsprävalenzen bei jüngeren Senioren (65-Bis 74-Jährige): Zahnverlust und prothetische Versorgung. In Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS V); Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2016; pp. 416–451. ISBN 978-3-7691-0020-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, T.; Hoffmann, T. Parodontalerkrankungen. In Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie; Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2016; pp. 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Barmer. BARMER Zahnreport 2020. Available online: https://www.barmer.de/presse/infothek/studien-und-reporte/zahnreporte/zahnreport-2020-1058930 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Kiyak, H.A.; Reichmuth, M. Barriers to and enablers of older adults’ use of dental services. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB)—Elftes Buch (XI)—Soziale Pflegeversicherung; Artikel 1 Des Gesetzes Vom 26. Mai 1994, BGBl. I S. 1014; Bundesministerium der Justiz: Berlin, Germay, 2014.

- DESTATIS (Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden) Pflegestatistik. Pflege Im Rahmen Der Pflegeversicherung. Ländervergleich—Pflegebedürftige. 2019. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Pflege/Publikationen/Downloads-Pflege/laender-pflegebeduerftige-5224002199004.pdf;jsessionid=F89F477E7B32F748A489AB550BD4E1C8.live742?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Pflege-Wissen. Pflegegrade und Neuer Pflegebedürftigkeitsbegriff. 2020. Available online: http://www.pflegestaerkungsgesetz.de/pflege-wissen-von-a-bis-z/pflege-details/erklaerung/pflegegrade-und-neuer-pflegebeduerftigkeitsbegriff/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Lauritano, D.; Moreo, G.; Della Vella, F.; Di Stasio, D.; Carinci, F.; Lucchese, A.; Petruzzi, M. Oral Health Status and Need for Oral Care in an Aging Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rapp, L.; Sourdet, S.; Vellas, B.; Lacoste-Ferré, M.-H. Oral Health and the Frail Elderly. J. Frailty Aging 2017, 6, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, I.; Micheelis, W. Krankheits-und Versorgungsprävalenzen bei älteren Senioren mit Pflegebedarf. In Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS V); Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (IDZ): Köln, Germany, 2016; pp. 557–578. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, C.; Zenthöfer, A.; Aurin, K.; Schoilew, K.; Wohlrab, T.; Sekundo, C. Oral Health of Centenarians and Supercentenarians. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 62, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A.J. Updating the Epidemiological Transition Model. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandersson, G. The Demographic Transition: Model and Reality. Fennia 1981, 159, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Inaba, H.; Saito, R.; Bacaër, N. An Age-Structured Epidemic Model for the Demographic Transition. J. Math. Biol. 2018, 77, 1299–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, K.B.; Shaid, E.; McCauley, K.; Pauly, M.V.; Naylor, M.D. Continuity of Care: The Transitional Care Model. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2015, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, V.; Gangireddy, S.; Mehrotra, A.; Ginde, R.; Tormey, M.; Meltzer, D. Ability of Hospitalized Patients to Identify Their In-Hospital Physicians. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krumholz, H.M. Post-Hospital Syndrome—An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vogeli, C.; Shields, A.E.; Lee, T.A.; Gibson, T.B.; Marder, W.D.; Weiss, K.B.; Blumenthal, D. Multiple Chronic Conditions: Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Implications for Quality, Care Management, and Costs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schumacher, K.L.; Meleis, A.I. Transitions: A Central Concept in Nursing. Image J. Nurs. Sch. 1994, 26, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morkisch, N.; Upegui-Arango, L.D.; Cardona, M.I.; van den Heuvel, D.; Rimmele, M.; Sieber, C.C.; Freiberger, E. Components of the Transitional Care Model (TCM) to Reduce Readmission in Geriatric Patients: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, M.; Outumuro, M.B.; Giber, F.; Pino, C.; Mattiussi, M.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Boietti, B.; Saimovici, J.; Gallo, C.; Hornstein, L.; et al. Geriatric Co-Management and Interdisciplinary Transitional Care Reduced Hospital Readmissions in Frail Older Patients in Argentina: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennito, S.H.; Clark, J.K. Transition Medicine: A Review of Current Theory and Practice. South Med. J. 2010, 103, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, J.; Wozow, C.; Peacock, C. Transition to Adult Care. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 31, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrouiguet, S.; Perez-Rodriguez, M.M.; Larsen, M.; Baca-García, E.; Courtet, P.; Oquendo, M. From EHealth to IHealth: Transition to Participatory and Personalized Medicine in Mental Health. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesellschaft für Transitionsmedizin e.V. Ziele Der “Gesellschaft für Transitionsmedizin e.V.”. Available online: https://transitionsmedizin.net/index.php/ueber-uns/verein/unsere-ziele (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Virtuelle Unternehmen. Transitionskompetenz. 2022. Available online: https://virtuelleunternehmen.wordpress.com/web-dossier-das-virtuelle-unternehmen/kapitel-drei/transitionskompetenz/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Schneidewind, U. Wie Systemübergänge nachhaltig gestaltet werden können. Ökologisches Wirtschaften-Fachzeitschrift 2010, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hafkesbrink, J.; Evers, J.; Knipperts, J.; Spitzner, G.; Wöhrmann, T. Transition-Management-Modell “Demografischer Wandel und Innovationsfähigkeit”; RIAS eV.: Duisburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, I.; Hahnel, S.; Jockusch, J. Health-Related Social and Ethical Considerations towards the Utilization of Dental Medical Services by Seniors: Influencing and Protective Factors, Vulnerability, Resilience and Sense of Coherence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleiel, D.; Nitschke, I.; Noack, M.J.; Barbe, A.G. Impact of Care Level, Setting and Accommodation Costs on a Newly Developed Oral Care Nursing Plan Format for Elderly Patients with Care Needs—Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, S.; Giacaman, R.A. Proposal for a Conceptual Framework for the Development of Geriatric Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, R.L.; Marchini, L. Cohort Differences among Aging Populations: An Update. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addazio, G.; Santilli, M.; Sinjari, B.; Xhajanka, E.; Rexhepi, I.; Mangifesta, R.; Caputi, S. Access to Dental Care-A Survey from Dentists, People with Disabilities and Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).