Abstract

Carbapenems are antibiotics of pivotal importance in human medicine, the efficacy of which is threatened by the increasing prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE). Urban ponds may be reservoirs of CRE, although this hypothesis has been poorly explored. We assessed the proportion of CRE in urban ponds over a one-year period and retrieved 23 isolates. These were submitted to BOX-PCR, PFGE, 16S rDNA sequencing, antibiotic susceptibility tests, detection of carbapenemase-encoding genes, and conjugation assays. Isolates were affiliated with Klebsiella (n = 1), Raoultella (n = 11), Citrobacter (n = 8), and Enterobacter (n = 3). Carbapenemase-encoding genes were detected in 21 isolates: blaKPC (n = 20), blaGES-5 (n = 6), and blaVIM (n = 1), with 7 isolates carrying two carbapenemase genes. Clonal isolates were collected from different ponds and in different campaigns. Citrobacter F6, Raoultella N9, and Enterobacter N10 were predicted as pathogens from whole-genome sequence analysis, which also revealed the presence of several resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. We found that blaKPC-3 was located on Tn4401b (Citrobacter F6 and Enterobacter N10) or Tn4401d (Raoultella N9). The former was part of an IncFIA-FII pBK30683-like plasmid. In addition, blaGES-5 was in a class 3 integron, either chromosomal (Raoultella N9) or plasmidic (Enterobacter N10). Our findings confirmed the role of urban ponds as reservoirs and dispersal sites for CRE.

1. Introduction

The spread of antimicrobial resistance and the upsurge in multidrug-resistant bacteria over the last decades led to an unprecedented impact on public health systems all around the globe, causing an ever-rising death toll accompanied by a significant economic impact [1,2,3]. Moreover, therapeutic options used to treat infectious diseases are becoming increasingly scarce, and even last-resort antibiotics are losing their efficacy [4].

Carbapenems, which are among the most active and potent agents against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens, are becoming threatened by the global dissemination of carbapenem-resistant bacteria, in which carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) play an important role [5]. As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included CRE in the list of critical targets for research and development of new antibiotics [6]. The two main mechanisms behind carbapenem resistance in CRE consist of the expression of cephalosporinases combined with mutation-derived permeability defects and, even more important, in carbapenemase production, enzymes that are able to efficiently hydrolyze carbapenem antibiotics [7]. KPC appears to dominate over other carbapenemases in Portugal, being associated with significant outbreaks of both KPC-2 and KPC-3 variants [8,9,10]. Carbapenemase-producing bacteria have also been isolated from several different Portuguese environmental settings, namely river water (IMP-, VIM-, KPC-, GES-, and NDM-producing strains) [11,12,13], wastewater (KPC-producing) [14], urban streams (GES-producing) [15], and wildlife (OXA-48-, GES- and KPC-producing) [16]. Carbapenemase-coding genes are usually located in association with mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that enable their spread through horizontal transfer [17]. For instance, the blaKPC gene has already been described in many different conjugative plasmids, and the transfer between these structures has been potentiated by the Tn3-based composite transposon Tn4401 [11,12,14,16,18]. In turn, blaGES genes are often associated with integrons within plasmids that carry other antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) [11,19,20].

Currently, the role of aquatic environments in the accumulation and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs, including CRE and carbapenemase-encoding genes, is well recognized [21,22]. In parallel, the surge in the application of the One Health approach has highlighted the link between anthropogenic contamination and the accumulation of antibiotic resistance in environmental habitats [23,24].

Lately, the importance of rivers within the environmental resistome framework has been evidenced, given their role in transporting resistant bacteria and ARGs and the fact that intense human activity in these ecosystems enables exposure to these bacteria and genes [11,21,25]. However, other aquatic systems such as urban lakes and ponds, which have been much less studied, are also extensively impacted by human activities and may constitute hotspots of antibiotic resistance [26]. These systems consist of natural or artificial inland bodies of surface water, surrounded by an urban environment and therefore often used for recreational purposes [27,28]. Unlike in rivers, resistant pathogens and ARGs undergo longer retention times in urban lakes and ponds [29], and the high bacterial density can promote the horizontal transfer of ARGs, enhancing the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains [30,31]. However, despite the potential role of urban lakes and ponds to accumulate and spread antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs, only recently have these aquatic systems begun to be explored. A few studies have revealed a high abundance and diversity of ARGs and MGEs, as well as the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant human pathogens. CRE and carbapenemase coding genes have been sporadically detected [29,32,33,34,35], but the available information is clearly insufficient to understand the potential risks associated with these environments. In addition, although the seasonal dynamics of antibiotic resistance has been accessed in these systems [36,37], to best of our knowledge, there is no information on the ability of CRE to persist in urban ponds over time.

The aim of this study was to: (i) assess the occurrence of CRE in water samples obtained from urban aquatic systems located in the urban area of Aveiro (Portugal); (ii) understand which mechanisms of carbapenem resistance are present in environmental CRE; and (iii) characterize CRE isolates in terms of antibiotic resistance, genetic platforms associated with carbapenemase genes, plasmid content and other MGEs, and virulence traits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation of CRE

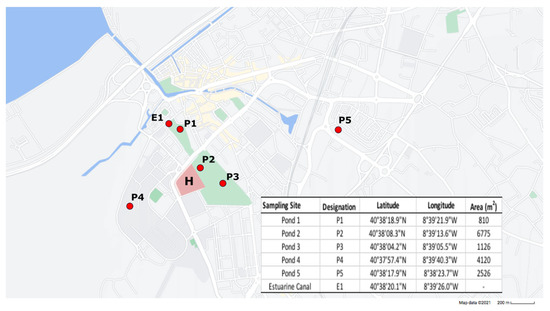

Between February 2019 and February 2020, surface water samples were collected from five ponds (P1–P5) located within or in close proximity to urban parks in Aveiro, a city that comprises about 55,000 inhabitants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map depicting the location, designation and coordinates of the sampled ponds (P1–P5) and estuarine canal (E1). Green areas indicate the location of urban parks, while blue areas represent the Ria de Aveiro urban canals. The location of the municipal hospital is also denoted (H).

Samples from an estuarine canal (E1), located directly downstream from Pond 1, were also included to investigate a possible connection between these systems. Due to logistic constraints, in both February and March 2019, samples were only collected from ponds P1 and P2, while in September 2019, no samples were collected from the estuarine canal E1. Samples were collected in sterile bottles and stored at 4 °C until analysis. Water samples were filtered in triplicate through mixed cellulose ester membranes (GN-6 Metricel®) with a 0.45 μm pore size. The filter membranes were then transferred to m-Fecal Coliform agar (m-FC) (VWR) plates supplemented with imipenem (4 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. To estimate the proportion of imipenem-resistant bacteria, m-FC without antibiotic was used. Coliform colonies were counted, and imipenem-resistant colonies were purified and stored in 20% glycerol at −80 °C.

2.2. Molecular Typing and Identification

Whole-cell suspensions were used as the DNA template for each isolate in all PCR analysis. Briefly, one bacterial colony of each isolate was resuspended in 20 µL of sterile distilled water, and 1 µL of this suspension was used as template in each PCR reaction. BOX-PCR (primers and conditions as described in Tacão et al., 2012 [38]) was used as a first discriminatory molecular-typing method for imipenem-resistant isolates. Isolates recovered from each sampling site exhibiting different BOX-profiles were selected for amplification and analysis of the 16S rRNA gene using the primers listed in Table S1. Additionally, considering the lack of accuracy of most phenotypic tests in the identification of Raoultella species, all isolates affiliated with the genus Raoultella were further identified using matrix-laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (Bruker MALDI Biotyper IVD, Portugal) in order to obtain a reliable species identification [39].

CRE isolates with different BOX profiles or collected in different sampling campaigns and from different ponds were further analyzed by PFGE of XbaI-digested DNA, using the CHEF-DR II System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) as previously described [40]. PFGE patterns were analyzed using GelCompar II software (v 6.1) with the criteria established by Tenover and colleagues [41].

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Screening of ARGs

To estimate the resistance levels of the CRE isolates, antimicrobial resistance was tested by the disk-diffusion method, in agreement with the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [42]. The following panel of 16 antibiotic was used: amikacin (AK), aztreonam (ATM), cefepime (FEP), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), ciprofloxacin (CIP), chloramphenicol (C), ertapenem (ETP), gentamicin (CN), imipenem (IPM), meropenem (MEM), piperacillin (PRL), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SXT), tetracycline (TE), and tigecycline (TGC) (Oxoid). Quality control was performed using Escherichia coli ATCC 25922. EUCAST clinical breakpoints (version 10.0, 2020) were used to classify the CRE isolates as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant. Isolates were screened for the presence of carbapenemase-encoding genes (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaKPC, blaGES, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48) and integron coding genes of classes 1, 2, and 3 using primers previously described (Table S1). Isolates were also tested using PCR for the presence of the colistin-resistance gene mcr-1 and the ESBL-coding gene blaCTX-M (Table S1), given the clinical relevance of these genes [43,44] and their previous detection in CRE [45,46].

2.4. Mating Assays and Plasmid Analysis

Mating assays were performed for CRE harboring carbapenemase genes that exhibited unique PFGE patterns, as previously described [47]. In short, donor strains and the sodium-azide-resistant strain E. coli J53 (recipient strain) were grown overnight in Luria–Bertani broth (LB) at 37 °C and 180 rpm. Donor and recipient strains were mixed at a 1:1 ratio on solid media using plate count agar (PCA) and left overnight at 37 °C. Putative transconjugants were selected on PCA plates supplemented with imipenem (4 μg/mL) and sodium azide (100 μg/mL). Transconjugants identity was confirmed with BOX-PCR typing and PCR confirmation of the acquired carbapenemase gene. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) gradient strips (Liofilchem, Italy) were used to evaluate the susceptibility of donors, transconjugants, and the recipient strain to imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, ceftazidime, and cefotaxime, following the EUCAST MIC clinical breakpoints [42].

Plasmid DNA was extracted using the NZYMiniprep kit (NZYTech, Portugal) following the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed by electrophoresis. Plasmid replicon typing (PBRT) was performed to detect replicons belonging to 18 incompatibility groups, as previously described [48]. We also evaluated the presence of pBK30661- and pBK30683-like plasmids, as described before [49].

2.5. Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis

Three CRE isolates were selected for whole-genome sequence (WGS) based on molecular typing and both antibiotic-resistance phenotype and genotype. Genomic DNA was extracted from each isolate using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Paired-end libraries were created using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The raw reads quality was verified using FastQC software and submitted to the trimming process in order to exclude those that contained a phred quality score below 20 using Trimmomatic v.0.36 [50]. The genomes were assembled using the SPAdes version 3.14.0 program [51]. Draft genomes were annotated using Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) [52]. The rRNA were predicted using the RNAmmer 1.2 Server [53], and tRNA were predicted using tRNAscan-SE 2.0 [54]. In order to confirm species identification, ANIb and ANIm were calculated by using the JSpeciesWS tool [55], and dDDH was calculated against representative genomes by using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator v2.1 [56]. We also considered the G + C% divergence in the overall genome-relatedness analysis [57]. Sequence types were attributed through a multilocus sequence typing analysis using MLST v2.0 [58] and PubMLST v1 [59]. ARGs were screened using CARD [60], and genomic islands were predicted using the Genomic Island Prediction Software (GIPSy) [61]. In silico screening of plasmid replicons was performed using PlasmidFinder v2.1 [62]. The CRISPR Finder tool [63] and the PHASTER tool [64] were used to assess the presence of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) and prophage sequences. Putative virulence factors were inspected using the Virulence Factors of Pathogenic Bacteria (VFDB) database [65]. The pathogenicities of all three CRE isolates were also accessed using PathogenFinder 1.1 [66].

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Diversity of CRE in Urban Ponds

Colony counts on mFC varied between 0.5 and 3.70 log10CFU/mL (Figure S1). Globally, P1 exhibited the highest average mean mFC counts/mL (3.02 log10), while P4 exhibited the lowest (1.05 log10). The February 2019 campaign was associated with overall higher mFC counts/mL, followed by December and March 2019.

Imipenem-resistant bacteria were detected in ponds P1, P2, and P3, and also in the estuarine canal E1. P1 and E1 were the only aquatic systems in which imipenem-resistant colonies were detected in all sampling campaigns. On the other hand, in pond P2, imipenem-resistant colonies were detected only in February and March 2019, and in pond P3 only in November 2019. Overall, the percentage of imipenem-resistant CFUs was low (0.021% on average), with the highest percentage (0.16%) occurring in site P1 in September 2019 (Table S2). A collection of 23 CREs was obtained in this study, isolated from sites P1 (n = 19), P3 (n = 2), and E1 (n = 2). Isolates were affiliated with the genera Citrobacter (n = 8), Raoultella (n = 11), Enterobacter (n = 3), and Klebsiella (n = 1) (Table 1). The MALDI-TOF analysis of the Raoultella isolates showed that they all were affiliated with Raoultella ornithinolytica. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of the imipenem-resistant bacteria found in Pond 2 demonstrated their affiliation with the Shewanella genus, which harbor intrinsic carbapenem-resistance mechanisms [67], and were consequently excluded from the CRE collection.

Table 1.

Features of CRE obtained from the urban ponds (P) and estuarine canal (E).

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility, ARGs and MGEs Content

The majority of the CRE collection was classified as multidrug resistant (approximately 87%), with the only exceptions being Enterobacter isolates (n = 3). The isolates were resistant to all β-lactams (Table 1), with the exception of the Klebsiella isolate, which was susceptible to cefepime and aztreonam. On the other hand, the CRE isolates were susceptible to tigecycline, with the exception of isolates Citrobacter F1 and F4. Additionally, the Enterobacter isolates were susceptible to all non-β-lactam antibiotics tested, excluding Enterobacter N10, which was resistant to ciprofloxacin. Within the Raoultella genus, all isolates were susceptible to tetracycline, tigecycline, and chloramphenicol.

With the exceptions of Enterobacter N11 and Enterobacter N15, CRE isolates harbored at least one of the inspected carbapenemase-encoding genes (Table 1); blaKPC was the most frequently identified (20 out of 23), being detected in all Raoultella and Citrobacter isolates, and also in Enterobacter N10. Furthermore, the Enterobacter N10 and Raoultella isolates (n = 5) collected in November 2019 coharbored both blaKPC and blaGES. The sequencing analysis revealed the presence of the blaGES-5 variant, which has been proven to exhibit carbapenemase activity [68]. The blaVIM gene was only detected in Citrobacter N5, which also harbored blaKPC. The single Klebsiella isolate in the collection harbored blaGES-5. Both blaCTX-M and mcr-1 genes were not detected.

The CRE collection was also inspected for the presence of integrons. The gene IntI1 was detected in all CRE isolates, except for Enterobacter N11, Enterobacter N15, and Klebsiella N14. IntI3 was identified in Klebsiella N14. Moreover, with the exception of Raoultella N1, all isolates that were collected in November 2019 in which both blaKPC and blaGES-5 were detected also coharbored both integrase-encoding genes IntI1 and IntI3. Class 2 integrons were not detected (Table 1).

The genetic context of the blaVIM gene identified in Citrobacter N5 was determined by PCR and sequence analysis, revealing the presence of this gene in a class 1 integron containing other ARGs encoding resistance to aminoglycosides (aacA4; aadA1), chloramphenicol (catB2), and sulfonamides (sul1). Further PCR analysis also revealed the presence of the blaGES-5 gene cassette as part of a class 3 integron in all isolates in which this gene was detected.

3.3. CRE Clonal Relatedness

Clonal relationships among the CRE isolates were first assessed using BOX-PCR (Table 1). Among the Citrobacter genus, the same BOX profile was observed within a group comprising isolates collected in February 2019 and N6 (collected in November 2019). In regard to the Enterobacter genus, both isolates N11 and N15, collected from Pond 3, shared the same BOX profile; while isolate N10, collected from Pond 1, exhibited a singular BOX profile. Within the Raoultella genus, two clusters exhibiting two distinctive BOX profiles were observed, one composed of all Raoultella isolates collected from Pond 1 in September and October 2019, and the other composed of all Raoultella isolates collected in November 2019 from sampling sites P1 and E1. Although we adopted the criteria of different BOX profiles and/or sampling campaigns/sites in the selection of CRE for PFGE analysis, isolates obtained from sampling site E1 (N12 and N13) were both selected due to the PCR detection of pBK30683-like plasmid exclusively on Raoultella N12.

The PFGE analysis further divided Raoultella isolates into two different clusters (Figure S2). One of the clusters comprised isolates collected in November 2019, with isolate N12 exhibiting a slightly different PFGE profile. The other cluster was composed of Raoultella isolates collected in October 2019 and isolate S1 from the September campaign. Regarding the Citrobacter genus, PFGE analysis resulted in two singletons represented by N5 and F5 (Figure S2), and one cluster comprising two separate clades with isolates collected in February and November. Together, the results obtained with BOX and PFGE confirmed the presence of clonal isolates in different ponds (Raoultella N1, N8, and N9 in pond P1 and Raoultella N12 in pond E1) and collected in different campaigns (Raoultella S1 and O1 in September and October 2019, respectively; Raoultella N1 in November 2019 and Raoultella N8, N9, and N12 in November 2020; and finally Citrobacter F1 and N6 in February 2019 and November 2020, respectively).

3.4. Plasmid Analysis and Transfer of Carbapenem Resistance

The presence of plasmids was evaluated in all CRE isolates (Figure S3), and 10 distinct plasmid profiles were identified. Within the Citrobacter genus, four distinctive plasmid profiles were detected. Regarding the Raoultella genus, all isolates collected in November exhibited the same plasmid profile. Raoultella O5 exhibited a singular plasmid profile, while Raoultella O1 and all isolates collected in September shared the same plasmid profile. Among the Enterobacter isolates, two distinct plasmid profiles were identified. The single Klebsiella isolate (N14) also showed a unique plasmid profile.

Two known plasmid replicons were detected by PBRT, namely IncL/M and IncN (Table 1). IncL/M was detected in Enterobacter N10 and both Citrobacter F4 and F6, while IncN was detected in Citrobacter isolates F3, F6, N5, and N6. Additionally, both replicons were detected in Citrobacter F6. The IncFIA-FII pBK30683-like plasmid structure was present in Raoultella isolates N1, N9, and N12 (Table 1).

The mating assays resulted in two transconjugants from Citrobacter isolates F1 and N6. Transconjugants carrying the blaKPC gene exhibited significant MIC increases for carbapenems (from to 5 to 62 times) and cephalosporins (from 187 to 680 times) (Table 2). Transfer frequencies (transconjugants per recipient cell) of blaKPC-harboring plasmids to E. coli J53 were 1.56 × 10−4 for Citrobacter F1 and 5.18 × 10−4 for Citrobacter N6.

Table 2.

MICs of carbapenems and cephalosporins for Citrobacter isolates F1 and N6, transconjugants E. coli J53::KPC, and recipient strain E. coli J53.

3.5. WGS Analysis

Three CRE isolates representing the three most represented genera were selected for WGS and further analysis: Citrobacter F6, R. ornithinolytica N9, and Enterobacter N10. The general genomic features of all three genomes are described in detail in Table S3.

Whole-genome sequence-based methods (ANIb, ANIm, dDDH, and G + C difference) were congruent in the identification of Citrobacter F6 as Citrobacter freundii, Raoultella N9 as Raoultella ornithinolytica, and Enterobacter N10 as Enterobacter kobei (Table S3). Furthermore, all three strains were predicted as human pathogens by PathogenFinder.

3.5.1. C. freundii F6

The C. freundii F6 draft genome was 5,117,230 bp in size and organized in 230 contigs, with 51.7% in terms of G + C content, an N50 of 88,228, and 4997 predicted coding sequences (Table S3). C. freundii F6 belonged to the sequence type ST270 (Table S3), and based on WGS analysis, a total of 142 virulence factors were predicted; they were distributed in a total of 16 virulence categories, with most allocated to secretion systems (n = 33), antiphagocytosis (n = 22), and adherence (n = 17) functions (Figure S5).

In addition to blaKPC-3, the ARGs identified on C. freundii F6 consisted of the Amp-C β-lactamase-coding gene blaCMY-152, dfrA14 (trimethoprim resistance), tetA (tetracycline resistance), and qnrS1 (quinolone resistance), the latter being commonly present in plasmid structures [69] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Putative ARGs and plasmids predicted by CARD and PlasmidFinder, respectively, in CRE isolates.

In fact, a BLAST search revealed that the contig in which qnrS1 was located (3259 bp in size) exhibited 100% similarity in terms of nucleotide identity with part of a 249.6 Kb plasmid previously described in a Salmonella enterica isolate (CP039857). Additional ARGs, namely blaOXA-1 (encoding β-lactam resistance), catB3 (chloramphenicol resistance), aacA4-cr (aminoglycoside resistance), mphA (encoding macrolide resistance), and sul1 (encoding sulfonamide resistance) (Table 3) were found within a class 1 integron (In1387) previously described in the IncN3 broad-host-range plasmid pTRE-132 [70], exhibiting the following gene cassette array: 5′CS IntI1|aacA4-cr|blaOXA-1|catB3|qacΔ1|sul1. Botts and colleagues captured the pTRE-132 plasmid from wetland bacteria into an E. coli recipient strain that was able to further transfer it through conjugation, resulting in resistance to ampicillin and ticarcillin, as well as decreased susceptibility to other classes of antibiotics (fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, aminoglycosides, and sulfonamides) [70]. This plasmid also harbors other ARGs, namely qnrB and an additional copy of sul1 [70].

In terms of MGEs, six replicons were detected in C. freundii F6, namely pKPC-CAV1321, IncFIA (HI1), IncFII (K), IncM1, and IncN (Table 3). Further genomic analysis led to the identification of 14 putative pathogenicity islands, 6 putative resistance islands, 2 CRISPR sequences, and 5 intact prophage regions (Figure S4). The sequence analysis of these genomic islands identified coding sequences that were part of a mercury-resistance operon, a type IV secretion system, and multidrug-efflux transporters responsible for the transport of metals.

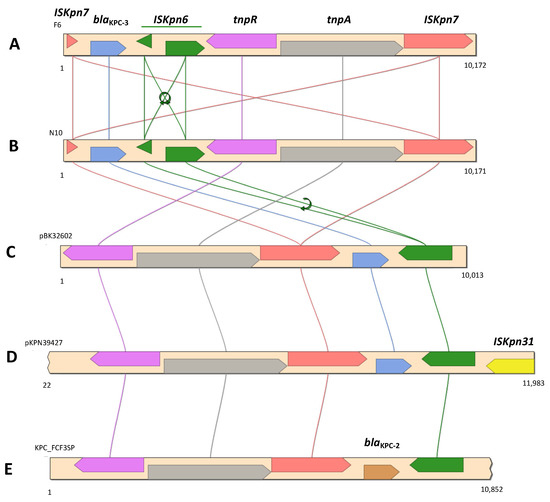

Next, blaKPC-3 was identified by GIPSy as being part of resistance island RI5 (Figure S4A). In addition to blaKPC-3, RI5 also harbored a gene coding for a multidrug-efflux transporter. The carbapenemase-encoding gene was flanked by two insertion sequences, ISKpn6 and ISKpn7, which in turn were part of a Tn4401b transposon (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic context of blaKPC-3 in C. freundii F6 (A), E. kobei N10 (B), E. coli BK32602 (C) (KU295134), K. pneumoniae strain 39427 (D) (CP054266), and K. pneumoniae FCF3SP (E) (CP004367).

The Tn4401b isoform was confirmed, as no deletions were observed in the 386 bp region [71]. However, both ISKpn6 and ISKpn7 were fragmented (Figure 2). The blaKPC-3-harboring contig (10,172 bp) revealed the same nucleotide sequence (100% identity; query coverage of 98%) with the corresponding region of an IncN plasmid described in a clinical E. coli strain (KU295134), and 99.7% of nucleotide sequence similarity (query coverage of 97%) with one other IncN plasmid described in several K. pneumoniae clinical strains [72], and also with a IncFIB/FII plasmid identified in a K. pneumoniae clinical strain (CP054266) [73].

3.5.2. R. ornithinolytica N9

The R. ornithinolytica N9 draft genome was 6,252,962 bp in size and organized in 420 contigs, with 55.2% in terms of G + C content, an N50 of 109,201, and 6014 predicted coding sequences (Table S3). A total of 130 virulence factors were predicted for R. ornithinolytica N9 across 12 virulence categories, with adherence (n = 44), iron uptake (n = 34), and secretion systems (n = 20) being the most represented (Figure S5).

The genomic analysis of R. ornithinolytica N9 confirmed the presence of a cointegrated IncFIA/FII plasmid, designated pN9KPC, exhibiting 99.93% similarity in terms of the nucleotide sequence with pBK30683 (KF954760), previously identified with the PCR-based protocol (Table 3) [49]. In addition to blaKPC-3, other resistance determinants previously reported in pBK30683-like plasmids were detected, including blaTEM-1, blaOXA-9 (encoding β-lactam resistance), aacA4, aadA1, strB, strA (aminoglycoside resistance), sul2 (sulfonamide resistance), and dfrA14 (trimethoprim resistance), which were also detected in pN9KPC (Table 3). The dfrA14 gene was part of the putative resistance island RI3 located in the same plasmid. Within this plasmid, the blaKPC-3 gene was located on a Tn4401d transposon, flanked by the insertion sequences ISKpn6 and ISKpn7, as previously described [49].

The analysis of the blaGES-5 gene context revealed its location in a class 3 integron, followed by part of an aacA4 gene cassette. However, the contig ended at this cassette, and it was not possible to clarify the full composition of this integron. A gene encoding an ORN β-lactamase, blaORN-1, intrinsic in R. ornithinolytica chromosome [74], was also detected on the same contig of blaGES-5.

Other resistance determinants were found in the N9 genome, including blaOXA-10 (β-lactam resistance), fosA (fosfomycin resistance), and the AmpC β-lactamase-encoding gene blaMOX-3, which was located in the same contig as a class 1 integrase and the ARGs msrE and mphE (macrolide resistance) (Table 3).

In addition to pN9KPC, three other additional replicons were detected in R. ornithinolytica N9, namely Col(MGD2), Col(pHAD28), and Col440I (Table 3). A total of 13 putative pathogenicity islands, 3 putative resistance islands, 7 CRISPR sequences, and 6 intact prophage regions were identified (Figure S4).

3.5.3. E. kobei N10

The predicted E. kobei N10 draft genome was 5,397,864 bp in size and organized in 431 contigs, with 54.4% in terms of G+C content, an N50 of 65,421, and 5128 predicted coding sequences (Table S3). E. kobei N10 was assigned to the new sequence type ST1378, as a result of the new alleles detected in fusA, leuS, and rpiB genes (Table S3). A total of 152 virulence factors were predicted for E. kobei N10, distributed over 15 virulence categories and with secretion systems (n = 45), iron uptake (n = 26), and antiphagocytosis (n = 24) being the most represented (Figure S5).

Apart from blaKPC-3 and blaGES-5, other ARGs were also detected in E. kobeii N10, specifically the AmpC β-lactamase-encoding gene blaACT-9, aacA4, mphA, sul1, and fosA (fosfomycin resistance) (Table 3).

Overall, six replicons were detected by PlasmidFinder, namely pKPC-CAV1321, CoI440I, IncFIB, IncM1, IncN, and IncX5 (Table 3). A total of 17 putative resistance islands and 21 putative pathogenicity islands were detected in the GIPSy analysis, as well as 2 CRISPR sequences and 3 intact prophage regions (Figure S4).

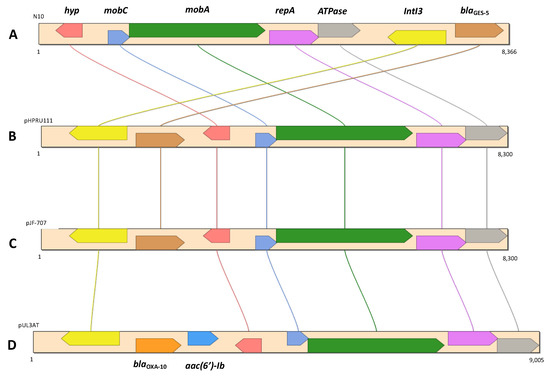

Next, blaGES-5 was identified as part of a putative resistance island (RI17), as well as the fosA coding for fosfomycin resistance (RI7). We also found that blaGES-5 was present in a class 3 integron, which in turn was located in a contig (8366 bp) approximately 99.8% identical in terms of nucleotide identity to a corresponding region in plasmids pHPRU11 (MN180807), described in the clinical strain E. cloacae Ecl-w [75]; pJF-707 (KX946994), found in the clinical strain K. oxytoca H143640707; and pUL3AT (HE616889), found in E. cloacae LIM73 isolated from hospital effluent [76] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Genetic context of blaGES-5 in E. kobei N10 (A), E. cloacae Ecl-W (B) (MN180807), K. oxytoca strain H143640707 (C) (KX946994), and E. cloacae LIM73 (D) (HE616889).

On the other hand, the blaKPC-3 gene was identified in a Tn4401b transposon, which in turn was located in a contig (10.17 Kb) that was 100% identical in terms of nucleotide sequence to the same region of the C. freundii F6 plasmid described above (Figure 3). These two isolates also had in common the presence of the ARGs aacA4, mphA, and sul1.

4. Discussion

Although we are witnessing an increase in the global levels of carbapenem resistance, the number of studies investigating the occurrence of CRE in urban lakes and ponds is still limited. In Portugal, reports on the occurrence of CRE in aquatic environments are still very scarce, and are limited to rivers [11,12,13,76] and wastewater effluents [14,19,77].

Urban lakes and ponds can serve as significant reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs, and contribute to their spread due to the likely exposure of humans and animals; for example, during recreational activities [26,78]. On the other hand, in some cases these systems are physically connected to other aquatic systems in which the spread of antibiotic resistance can occur by other routes, such as estuarine channels. In this study, we reported the presence and characterization of CRE collected from five urban ponds and an estuarine canal located in the Aveiro city center.

Overall, the colony counts on mFC media (Figure S1) never exceeded the value corresponding to a fair classification of superficial waters (third-best classification possible out of five categories that varied from excellent to very poor) in terms of total coliforms, according to the criteria used by the National System of Information on Hydric Resources (SNIRH) to classify superficial water (https://snirh.apambiente.pt, accessed on 13 December 2021). The low percentage of imipenem-resistant Enterobacterales (between 0 and 1%) was not surprising, as carbapenems are considered last-resort drugs that are used exclusively in clinical settings in Portugal [76]. Pond 1 stood out from the other sampling sites as the only site where imipenem-resistant Enterobacterales were detected in every sampling campaign (Table S2). In fact, roughly 84% of the CRE collection was obtained from Pond 1 (Table 1). This pond is located in Aveiro Municipal Park, where several contamination sources could be responsible for the higher CRE prevalence. CRE present in the fecal droppings from companion animals have been previously described [79,80], although with low prevalence. On the other hand, runoffs from surrounding areas or leaks in wastewater pipelines also represent plausible contamination sources [14,81], including from hospital wastewater [82], considering that the hospital is located approximately 600 m from Pond 1, and the hospital’s wastewater pipeline system is also located in close proximity. However, further research is needed to clarify the contamination source. Molecular typing revealed that Citrobacter and Raoultella isolates exhibiting the same BOX and PFGE profiles could be detected in Pond 1 over time spans of 10 months and 1 month, respectively. The presence over a long period of the same strains may indicate the existence of a persistent contamination source that is responsible for periodic discharges. At the same time, CRE occurring in these ponds are not submitted to any streams or currents, in contrast to rivers and larger aquatic systems. Therefore, without a significant water flow regime, CRE are not exposed to the resulting dilution effect, and tend to accumulate [78]. The occurrence of Raoultella isolates with the same PFGE pulsotype in Pond 1 and in the adjacent E1 canal indicated that P1 may be contributing to the dissemination of CRE to the canal and ultimately to Ria de Aveiro, in which the occurrence of Enterobacterales harboring integrons and β-lactamase genes has been previously reported [83]. This hypothesis points to an even more worrying scenario, since Ria de Aveiro is used as a food source, therefore providing an additional route through which humans can be exposed to CRE.

The β-lactam resistance observed in the CRE collection was mainly due to the presence of the carbapenemase genes blaKPC-3 and blaGES-5. The high frequency of blaKPC harboring CRE reflected the epidemiology observed in Portuguese hospitals, since it was the most frequent carbapenemase gene among CRE clinical isolates [9,84,85]. Furthermore, KPC was also the most common carbapenemase reported from environmental CRE in Portugal [11,12,14]. In contrast, Araújo and colleagues established a CRE collection obtained from raw wastewater in which blaGES-5 was detected in all isolates, including Citrobacter and Enterobacter isolates [19]. In addition, the occurrence of a GES-5-producing K. pneumoniae isolate recovered from an urban water stream has been described in Portugal [15]. As hypothesized by Araújo and colleagues [19], GES-5-producing CRE may originate from nonhuman sources.

Citrobacter species are known for their capacity to colonize humans, animals, plants, and the environment, and also are often associated with high-risk transferable ARGs such as carbapenemases [86]. The occurrence of environmental blaKPC-harboring Citrobacter has been previously described in rivers [25,87] and hospital effluents [88,89,90]. On the other hand, the copresence of blaKPC and blaVIM in Citrobacter has only been described once in a clinical C. freundii isolate in Spain [91]. In both the Spanish C. freundii clinical isolate and Citrobacter N5, blaVIM-1 was inserted in a class 1 integron containing five other ARGs: aacA4-dfrB1-aadA1-catB3-sul1, thus contributing to its MDR phenotype. C. freundii F6 belonged to sequence type ST270, which was first assigned to an isolate obtained from a diarrheal patient in China [92], showing that this ST is not confined to clinical settings, as it is disseminated across different continents.

In C. freundii F6, R. ornithinolytica N9, and E. kobei N10, the blaKPC-3 gene was present as part of a Tn3-based mobile transposon Tn4401 exhibiting two different isoforms: Tn4401b in C. freundii F6 and E. kobei N10; and Tn4401d in R. ornithinolytica N9, specifically in the pBK30683-like plasmid pN9KPC [49] (Figure 2). The mobile genetic platform blaKPC-3-Tn4401 appears to be widespread in CRE isolated from Portuguese hospitals [10,93,94], and has also been detected circulating in the environment [11,14], associated with both IncN and FIA/FII plasmids. The Tn4401 transposon has also been proven to have an important role in the dissemination of blaKPC-type genes within a large range of plasmid structures and bacterial species [18,95,96]. Although it was not possible to determine the type of plasmid structure in which the blaKPC-3 gene was located in C. freundii N6 and E. kobei N10, the replicons (e.g., IncN, IncX5, and pKPC-CAV1321) identified by the in silico analysis of both these isolates have already been associated with blaKPC in both clinical [91,96,97] and environmental isolates [35,98], including in Portugal [8,11,94].

CRE harboring pBK30683-like plasmids have already been reported in Portugal, namely in clinical K. pneumoniae isolates [94] and in environmental K. pneumoniae isolated from a highly polluted river [11]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that such plasmids have been described in Raoultella isolates.

Raoultella species are closely related to Klebsiella spp. and can be found ubiquitously in the environment, although they have already been associated with several cases of human infections linked to production of carbapenemases [99,100,101,102]. In addition, Raoultella isolates harboring carbapenemases have also been described in environmental settings, although never in Portugal [103,104,105,106]. Gomi and colleagues described the occurrence of blaGES-5 situated in a class 1 integron in a R. ornithinolytica strain isolated from wastewater [104]. In R. ornithinolytica N9, although this gene was likely present in chromosomal DNA, it was associated with a class 3 integron, which may play a potential role in the dissemination of this gene. R. ornithinolytica, previously known as K. ornithinolytica, is often misidentified as K. oxytoca by conventional biochemical identification methods [101,107]. Due to this common misidentification, the significance of Raoultella spp. as a nosocomial pathogen may be underestimated, as well as their association with carbapenemase production [108].

The role of the Enterobacter genus in carbapenemase gene flow between environmental, animal, and human settings has also been recognized [86,109]. Enterobacter isolates harboring blaKPC and blaGES genes have already been described in both clinical [110,111,112,113] and environmental settings [90,104].

In addition, in Portugal the blaGES-5 gene has already been found in association with IntI3 in clinical K. pneumoniae isolates [92], and also in two Citrobacter environmental isolates [11,19]. The occurrence of blaKPC-3 in Tn4401b transposons in both C. freundii F6 and E. kobei N10 highlighted the importance of these MGEs in the dissemination and acquisition of carbapenemase genes and other ARGs among different Enterobacterales species [114]. This was also pointed out by the occurrence of plasmids harboring the blaGES-5 gene that exhibited a high similarity to the one detected in E. kobei N10, in different Enterobacterales hosts isolated from environmental [11,19] and clinical settings [20] (Figure 3). Furthermore, the association of the blaGES-5 gene described in E. kobei N10 with a class 3 integrase and a genomic island enhances the chances of horizontal gene-transfer events [115,116].

The results obtained here highlighted that, although urban ponds are usually smaller and more confined than other aquatic systems, they are associated with bacteria that have a large variety of ARGs and also MGEs, which contribute to the dissimilation of these genes. The important role of conjugative plasmids was made clear, as these structures were identified in all CRE isolates, including previously described plasmids that were associated with dispersion of carbapenemase genes in clinical settings. In addition to plasmids, a considerable variety of MGEs were also identified, including genomic islands, transposons, and integrons. The importance of integrons was evidenced here, as they were linked with MDR phenotypes (in strains R. ornithinolytica N9, C. freundii F6, and Citrobacter N5) and the dispersion of carbapenemase genes (in strains R. ornithinolytica N9 and E. kobei N10).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study supported the evidence that urban landscape ponds can serve as hotspots for multidrug-resistant bacteria that are also resistant to last-resort antibiotics. It is also worrisome that the acquired carbapenemase genes described here were located in conjugative plasmids and at the same time were associated with other mobile genetic elements such as integrons and genomic islands.

The fact that CRE were detected in every sampling campaign and that the same strains were able to persist within these ponds over time represents a serious public health threat, and highlights the importance of adopting a One Health approach, in which the environment is viewed as a transmission vehicle of antimicrobial resistance.

Further investigation should focus on elucidating the source(s) of contamination with CRE, particularly in Pond 1, from which most of the CRE isolates were obtained. Moreover, the transmission of resistance from these urban aquatic systems to humans and the underlying clinical implications are still largely underexplored and should also be attained.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19105848/s1, Table S1: PCR primers used in molecular typing, 16S-rRNA-based affiliation, and screening of ARGs and integrons [76,117,118,119,120]. Table S2: Percentage of imipenem-resistant CFUs in the sampled ponds and estuarine canal in February and March 2019, and from September 2019 to February 2020. No imipenem-resistant colonies were obtained from Pond P4 and P5. Hyphens are exhibited whenever no imipenem-resistant CFUs were detected. Table S3: General features of C. freundii F6, R. ornithinolytica N9, and E. kobei N10 draft genomes, and WGS-based parameters used for phylogenetic affiliation. Figure S1: Average counting of typical coliforms in CFU/mL (log10) collected in February and March 2019, and from September 2019 to February 2020, from five ponds and an estuarine canal. In both February and March 2019, samples were only collected from ponds P1 and P2, while in September 2019, no samples were collected from E1. Figure S2: Dendrogram with the PFGE restriction patterns of genomic DNA from the eight Raoultella (A) and the seven Citrobacter (B) selected strains digested with XbaI. The dendrogram was constructed using GelCompar II version 6.1 (Applied Maths, Belgium) with a Dice coefficient and UPGMA clustering (Opt. 2.00%; Tol 1.0%; H > 0.0%; S > 0.0%). Figure S3: Plasmid DNA fingerprint of the entire CRE collection comprising 23 isolates. The molecular weight marker 1.5 Kb DNA NZYDNA Ladder VI (NzyTech, Portugal) is represented by the letter M. Figure S4: Circular genome representation of C. freundii F6 (A), R. ornithinolytica N9 (B), and E. kobei N10 (C). BRIG performed the alignment using a local BLAST+ with the standard parameters (50% lower-70% upper cut-off for identity and e-value of 10). The ring color gradients correspond to varying degrees of identity of BLAST matches. Circular genomic maps include information on GC skew, GC content, putative pathogenicity islands (PIs), putative resistance islands (RIs), prophage sequences (PS), and the location of ARGs and CRISPRs within the clockwise and counterclockwise CDS strands. Figure S5: Category of bacterial virulence factors found in C. freundii F6 (a), R. ornithinolytica N9 (b), and E. kobei N10 (c) according to the VFDB analysis.

Author Contributions

P.T.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft; N.P.: Methodology, Investigation; M.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision; I.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—Review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support by FCT/MCTES through national funds to CESAM (UIDP/50017/2020+UIDB/50017/2020 + LA/P/0094/2020), CFE (UIDB/04004/2020), and individual grants to P.T. (SFRH/BD/132046/2017) and M.T. (CEECIND/00977/2020).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Material files. Additionally, the whole-genome sequences of Citrobacter freundii F6, Raoultella ornithinolytica N9, and Enterobacter kobei N10 can be found in the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank database under the accession numbers JAJBJE000000000, JAJDEY000000000, and JAKKZG00000000, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. No Time to Wait: Securing the Future from Drug-Resistant Infections; Report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations; UN: Washigton, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskos, I.; Lagou, S.; Pontikis, K.; Rapti, V.; Poulakou, G. The “Old” and the “New” Antibiotics for MDR Gram-Negative Pathogens: For Whom, When, and How. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doi, Y. Treatment Options for Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S565–S575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Weinstein, R.A. The Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The Impact and Evolution of a Global Menace. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S28–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopes, E.; Saavedra, M.J.; Costa, E.; de Lencastre, H.; Poirel, L.; Aires-de-Sousa, M. Epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Northern Portugal: Predominance of KPC-2 and OXA-48. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 22, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Ortiz de la Rosa, J.M.; Gonçalves, M.L.; Pereira, A.L.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Hospital, Portugal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manageiro, V.; Ferreira, E.; Almeida, J.; Barbosa, S.; Simões, C.; Bonomo, R.A.; Caniça, M.; Castro, A.P.; Lopes, P.; Fonseca, F.; et al. Predominance of KPC-3 in a survey for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Portugal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3588–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, P.; Tacão, M.; Pureza, L.; Gonçalves, J.; Silva, A.; Cruz-Schneider, M.P.; Henriques, I. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a Portuguese river: blaNDM, blaKPC and blaGES among the detected genes. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Barbosa-Vasconcelos, A.; Simões, R.R.; Da Costa, P.M.; Liu, W.; Nordmann, P. Environmental KPC-producing Escherichia coli isolates in Portugal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1662–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kieffer, N.; Poirel, L.; Bessa, L.J.; Barbosa-vasconcelos, A. VIM-1, VIM-34, and IMP-8 Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli Strains Recovered from a Portuguese River. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2585–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mesquita, E.; Ribeiro, R.; Silva, C.J.C.; Alves, R.; Baptista, R.; Condinho, S.; Rosa, M.J.; Perdigão, J.; Caneiras, C.; Duarte, A. An update on wastewater multi-resistant bacteria: Identification of clinical pathogens such as Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131-producing CTX-M-15 ESBL and KPC-3 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella oxytoca. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manageiro, V.; Ferreira, E.; Caniça, M.; Manaia, C.M. GES-5 among the β-lactamases detected in ubiquitous bacteria isolated from aquatic environment samples. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 351, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Fournier, C.; Lopes, E.; Lencastre, H.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. High colonization rate and heterogeneity of ESBL- and carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from gull feces in Lisbon, Portugal. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naas, T.; Cuzon, G.; Villegas, M.V.; Lartigue, M.F.; Quinn, J.P.; Nordmann, P. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the β-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Araújo, S.; Sousa, M.; Tacão, M.; Baraúna, R.A.; Silva, A.; Ramos, R.; Alves, A.; Manaia, C.M.; Henriques, I. Carbapenem-resistant bacteria over a wastewater treatment process: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in untreated wastewater and intrinsically-resistant bacteria in final effluent. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, M.J.; Davies, F.; Jauneikaite, E.; Hopkins, K.L.; Turton, J.F.; Adams, G.; Pavlu, J.; Innes, A.J.; Eades, C.; Brannigan, E.T.; et al. A multispecies cluster of GES-5 carbapenemase–producing Enterobacterales linked by a geographically disseminated plasmid. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2553–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hooban, B.; Joyce, A.; Fitzhenry, K.; Chique, C.; Morris, D. The role of the natural aquatic environment in the dissemination of extended spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase encoding genes: A scoping review. Water Res. 2020, 180, 115880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.C.; Lee, J. The threat of carbapenem-resistant bacteria in the environment: Evidence of widespread contamination of reservoirs at a global scale. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Amado, S.; Coque, T.M.; Baquero, F.; Martínez, J.L. Defining and combating antibiotic resistance from One Health and Global Health perspectives. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkman, A.; Pärnänen, K.; Larsson, D.G.J. Fecal pollution explains antibiotic resistance gene abundances in anthropogenically impacted environments. Nat. Commun. 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleichenbacher, S.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Zurfluh, K.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Environmental dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in rivers in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, C.P.; Hu, A. Urban ponds as hotspots of antibiotic resistome in the urban environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 124008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.F.; Morris, D.; Schmitt, H.; Gaze, W.H. Natural recreational waters and the risk that exposure to antibiotic resistant bacteria poses to human health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 65, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.V.V.S.; Nandan, M.J. Urban Lakes and Ponds. Encycl. Earth Sci. Ser. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, C.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. Environmental risk characterization and ecological process determination of bacterial antibiotic resistome in lake sediments. Environ. Int. 2021, 147, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, N.; Laffite, A.; Graham, N.D.; Meijer, M.; Prabakar, K.; Mubedi, J.I.; Elongo, V.; Mpiana, P.T.; Ibelings, B.W.; Wildi, W.; et al. Accumulation of clinically relevant antibiotic-resistance genes, bacterial load, and metals in freshwater lake sediments in Central Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6528–6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Y.; Le, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H. Urban recreational water—Potential breeding ground for antibiotic resistant bacteria? J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 81, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finton, M.D.; Meisal, R.; Porcellato, D.; Brandal, L.T.; Lindstedt, B.-A. Whole Genome Sequencing and Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Bacterial Strains Isolated from a Norwegian University Campus Pond. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.Y.; Araújo, S.; Folador, A.R.C.; Ramos, R.T.J.; Azevedo, J.S.N.; Tacão, M.; Silva, A.; Henriques, I.; Baraúna, R.A. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria recovered from an Amazonian lake near the city of Belém, Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harmon, D.E.; Miranda, O.A.; McCarley, A.; Eshaghian, M.; Carlson, N.; Ruiz, C. Prevalence and characterization of carbapenem-resistant bacteria in water bodies in the Los Angeles-Southern California area. Microbiologyopen 2018, 8, e00692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nascimento, T.; Cantamessa, R.; Melo, L.; Lincopan, N.; Fernandes, M.R.; Cerdeira, L.; Lincopan, N.; Fraga, E.; Dropa, M.; Sato, M.I.Z. International high-risk clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae KPC-2/CC258 and Escherichia coli CTX-M-15/CC10 in urban lake waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, P.; Peng, F.; Gao, X.; Xiao, P.; Yang, J. Decoupling the dynamics of bacterial taxonomy and antibiotic resistance function in a subtropical urban reservoir as revealed by high-frequency sampling. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Su, J.; Gad, M.; Li, J.; Mulla, S.I.; Yu, C.; Hu, A. Fecal pollution mediates the dominance of stochastic assembly of antibiotic resistome in an urban lagoon (Yundang lagoon), China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacão, M.; Correia, A.; Henriques, I. Resistance to Broad-spectrum Antibiotics in Aquatic Systems: Anthropogenic Activities Modulate the Dissemination of blaCTX-M-Like Genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4134–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ponce-Alonso, M.; Rodríguez-Rojas, L.; del Campo, R.; Cantón, R.; Morosini, M.I. Comparison of different methods for identification of species of the genus Raoultella: Report of 11 cases of Raoultella causing bacteraemia and literature review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribot, E.M.; Fair, M.A.; Gautom, R.; Cameron, D.N.; Hunter, S.B.; Swaminathan, B.; Barrett, T.J. Standardization of Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis Protocols for the Subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2006, 3, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tenover, F.C.; Arbeit, R.D.; Goering, R.V.; Mickelsen, P.A.; Murray, B.E.; Persing, D.H.; Swaminathan, B. Interpreting Chromosomal DNA Restriction Patterns Produced by Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis: Criteria for Bacterial Strain Typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters Version 11.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Växjö, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance: An additional antibiotic resistance menace. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Ali, T.; Ali, I.; Khan, N.A.; Han, B.; Gao, J. The Growing Genetic and Functional Diversity of Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, C.; Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Occurrence of CTX-M-15- and MCR-1-producing Enterobacterales in pigs in Portugal: Evidence of direct links with antibiotic selective pressure. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manageiro, V.; Clemente, L.; Romão, R.; Silva, C.; Vieira, L.; Ferreira, E.; Caniça, M. IncX4 Plasmid Carrying the New mcr-1.9 Gene Variant in a CTX-M-8-Producing Escherichia coli Isolate Recovered from Swine. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Cruz, F. Horizontal Gene Transfer: Methods and Protocols, Springer Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Bertini, A.; Villa, L.; Falbo, V.; Hopkins, K.L.; Threlfall, E.J. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 2005, 63, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chavda, K.D.; Melano, R.G.; Hong, T.; Rojtman, A.D.; Jacobs, M.R.; Bonomo, R.A.; Kreiswirth, B.N. Molecular Survey of the Dissemination of two blaKPC-harboring IncFIA plasmids in New Jersey and New York Hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lagesen, K.; Hallin, P.; Rodland, E.A.; Staerfeldt, H.-H.; Rognes, T.; Ussery, D.W. RNAmmer: Consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3100–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.M.; Eddy, S.R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Oliver Glöckner, F.; Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: A web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 2015, 32, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Taxonomic use of DNA G+C content and DNA-DNA hybridization in the genomic age. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications [version 1; referees: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, A.G.; Waglechner, N.; Nizam, F.; Yan, A.; Azad, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Bhullar, K.; Canova, M.J.; De Pascale, G.; Ejim, L.; et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3348e3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soares, S.C.; Geyik, H.; Ramos, R.T.J.; de Sá, P.H.C.G.; Barbosa, E.G.V.; Baumbach, J.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Miyoshi, A.; Tauch, A.; Silva, A.; et al. GIPSy: Genomic Island prediction software. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 232, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; Garciá-Fernández, A.; Larsen, M.V.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Hasman, H. In Silico detection and typing of plasmids using plasmidfinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grissa, I.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRFinder: A web tool to identify clustered regularly interspace short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, S.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder—Distinguishing Friend from Foe Using Bacterial Whole Genome Sequence Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacão, M.; Araújo, S.; Vendas, M.; Alves, A.; Henriques, I. Shewanella species as the origin of blaOXA-48 genes: Insights into gene diversity, associated phenotypes and possible transfer mechanisms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, N.K.; Smith, C.A.; Frase, H.; Black, D.J.; Vakulenko, S.B. Kinetic and structural requirements for carbapenemase activity in GES-type β-lactamases. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, A.; Fortini, D.; Veldman, K.; Mevius, D.; Carattoli, A. Characterization of plasmids harbouring qnrS1, qnrB2 and qnrB19 genes in Salmonella. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botts, R.T.; Apffel, B.A.; Walters, C.J.; Davidson, K.E.; Echols, R.S.; Geiger, M.R.; Guzman, V.L.; Haase, V.S.; Montana, M.A.; La Chat, C.A.; et al. Characterization of Four Multidrug Resistance Plasmids Captured from the Sediments of an Urban Coastal Wetland. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheruvanky, A.; Stoesser, N.; Sheppard, A.E.; Crook, D.W.; Hoffman, P.S.; Weddle, E.; Carroll, J.; Sifri, C.D.; Chai, W.; Barry, K.; et al. Enhanced Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase Expression from a Novel Tn4401 Deletion. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00025-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Chaparro, P.J.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Queiroz, M.G.; De Lima, C.P.S.; Levy, C.E.; Pavez, M.; Lincopan, N.; Gonçalves, E.C.; Mamizuka, E.M.; Sampaio, J.L.M.; et al. Complete Nucleotide Sequences of Two blaKPC-2-Bearing IncN Plasmids Isolated from Sequence Type 442 Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Strains Four Years Apart. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2958–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satlin, M.J.; Chen, L.; Patel, G.; Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Weston, G.; Kim, A.C.; Seo, S.K.; Rosenthal, M.E.; Sperber, S.J.; Jenkins, S.G.; et al. Multicenter clinical and molecular epidemiological analysis of bacteremia due to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the CRE epicenter of the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02349-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walckenaer, E.; Poirel, L.; Leflon-Guibout, V.; Nordmann, P.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H. Genetic and Biochemical Characterization of the Chromosomal Class A β-Lactamases of Raoultella (formerly Klebsiella) planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barraud, O.; Casellas, M.; Dagot, C.; Ploy, M.C. An antibiotic-resistant class 3 integron in an Enterobacter cloacae isolate from hospital effluent. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E306–E308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tacão, M.; Correia, A.; Henriques, I. Low Prevalence of Carbapenem-Resistant Bacteria in River Water: Resistance Is Mostly Related to Intrinsic Mechanisms. Microb. Drug Resist. 2015, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Leonardo, I.C.; Nunes, M.; Silva, A.F.; Barreto Crespo, M.T. Environmental and pathogenic carbapenem resistant bacteria isolated from a wastewater treatment plant harbour distinct antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnadozie, C.F.; Odume, O.N. Freshwater environments as reservoirs of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torralba, A.; Oteo, J.; Asenjo, A.; Bautista, V.; Fuentes, E.; Alós, J.I. Survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in companion dogs in Madrid, Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2499–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yousfi, M.; Touati, A.; Muggeo, A.; Mira, B.; Asma, B.; Brasme, L.; Guillard, T.; de Champs, C. Clonal dissemination of OXA-48-producing Enterobacter cloacae isolates from companion animals in Algeria. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 12, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, H.; Kemper, M.A.; de Man, H.; van Leuken, J.P.G.; Schijven, J.F.; van Passel, M.W.J.; Schmitt, H.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Nationwide surveillance reveals frequent detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in Dutch municipal wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, N.; O’Connor, L.; Mahon, B.; Varley, Á.; McGrath, E.; Ryan, P.; Cormican, M.; Brehony, C.; Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.; et al. Hospital effluent: A reservoir for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.S.; Fonseca, F.; Alves, A.; Saavedra, M.J.; Correia, A. Occurrence and diversity of integrons and beta-lactamase genes among ampicillin-resistant isolates from estuarine waters. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, H.; Glasner, C.; Albiger, B.; Aanensen, D.M.; Tomlinson, C.T.; Tambić, A.; Cantón, R.; Carmeli, Y.; Friedrich, A.W.; Giske, C.G.; et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): A prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manageiro, V.; Romão, R.; Moura, I.B.; Sampaio, D.A. Molecular Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Enterobacteriaceae Isolates in Portuguese Hospitals: Results from European Survey on Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2001735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baquero, F.; Coque, T.M.; Martínez, J.L.; Aracil-Gisbert, S.; Lanza, V.F. Gene Transmission in the One Health Microbiosphere and the Channels of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Huang, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, B. First detection and genomics analysis of KPC-2-producing Citrobacter isolates from river sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, L.; Chen, H.; Ng, C.; Le, T.H.; Koh, T.H.; Barkham, T.; Sobsey, M.; Gin, K.Y.H. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase- producing bacteria from hospital effluents in Singapore. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Espedido, B.; Feng, Y.; Zong, Z. Citrobacter freundii carrying blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1: Characterization by whole genome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Lü, X.; Zong, Z. Enterobacteriaceae producing the KPC-2 carbapenemase from hospital sewage. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 73, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.; Arana, D.M.; Viedma, E.; Perez-Montarelo, D.; Chaves, F. Characterization of mobile genetic elements carrying VIM-1 and KPC-2 carbapenemases in Citrobacter freundii isolates in Madrid. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 307, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qin, L.; Hao, S.; Lan, R.; Xu, B.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, R.; Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Lv, X.; et al. Lineage, antimicrobial resistance and virulence of Citrobacter spp. Pathogens 2020, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perdigão, J.; Modesto, A.; Pereira, A.L.; Neto, O.; Matos, V.; Godinho, A.; Phelan, J.; Charleston, J.; Spadar, A.; de Sessions, P.F.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing resolves a polyclonal outbreak by extended-spectrum beta-lactam and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Portuguese tertiary-care hospital. Microb. Genomics. 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Bavlovic, J.; Machado, E.; Amorim, J.; Peixe, L.; Novais, Â. KPC-3-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Portugal Linked to Previously Circulating non-CG258 Lineages and Uncommon Genetic Platforms (Tn4401d-IncFIA and Tn4401d-IncN). Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5873–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheppard, A.E.; Stoesser, N.; Wilson, D.J.; Sebra, R.; Kasarskis, A.; Anson, L.W.; Giess, A.; Pankhurst, L.; Vaughan, A.; Grim, C.J.; et al. Nested Russian Doll-Like Genetic Mobility Drives Rapid Dissemination of the Carbapenem Resistance Gene blaKPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3767–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chavda, K.D.; Chen, L.; Jacobs, M.R.; Bonomo, R.A.; Kreiswirth, B.N. Molecular diversity and plasmid analysis of KPC-producing Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4073–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekizuka, T.; Yatsu, K.; Inamine, Y.; Segawa, T.; Nishio, M.; Kishi, N.; Kuroda, M. Complete Genome Sequence of a blaKPC-2 -Positive Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Isolated from the Effluent of an Urban Sewage Treatment Plant in Japan. mSphere 2018, 3, 414681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; DiPersio, J.R.; Kang, J.; Weinstein, M.P.; Jones, R.N. First Descriptions of blaKPC in Raoultella spp. (R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica): Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 4129–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demiray, T.; Koroglu, M.; Ozbek, A.; Altindis, M. A rare cause of infection, Raoultella planticola: Emerging threat and new reservoir for carbapenem resistance. Infection 2016, 44, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drancourt, M.; Bollet, C.; Carta, A.; Rousselier, P. Phylogenetic analyses of Klebsiella species delineate Klebsiella and Raoultella gen. nov.; with description of Raoultella ornithinolytica comb. nov.; Raoultella terrigena comb. nov. and Raoultella planticola comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovleva, A.; Mettus, R.T.; Mcelheny, C.L.; Griffith, M.P.; Shields, R.K.; Cooper, V.S. High-Level Carbapenem Resistance in OXA-232-Producing Raoultella ornithinolytica Triggered by Ertapenem Therapy Alina. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 64, e01335-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Xu, Z. Coexistence of the blaNDM-1-carrying plasmid pWLK-nDM and the blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid pWLK-KPC in a Raoultella ornithinolytica isolate. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomi, R.; Matsuda, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Chou, P.H.; Tanaka, M.; Ichiyama, S.; Yoneda, M.; Matsumura, Y. Characteristics of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Wastewater Revealed by Genomic Analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02501-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piedra-Carrasco, N.; Fàbrega, A.; Calero-Cáceres, W.; Cornejo-Sánchez, T.; Brown-Jaque, M.; Mir-Cros, A.; Muniesa, M.; González-López, J.J. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from a Spanish river ecosystem. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.; Huang, L.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Mao, D.; Luo, Y. Discharge of KPC-2 genes from the WWTPs contributed to their enriched abundance in the receiving river. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581–582, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Hong, K.H.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, S.H.; Song, S.H.; Song, K.H.; Kim, H.B.; Park, K.U.; Song, J.; Kim, E.C. Evaluation of three phenotypic identification systems for clinical isolates of Raoultella ornithinolytica. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seng, P.; Boushab, B.M.; Romain, F.; Gouriet, F.; Bruder, N.; Martin, C.; Paganelli, F.; Bernit, E.; Treut, Y.P.; Le, T.P.; et al. Emerging role of Raoultella ornithinolytica in human infections: A series of cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 45, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peirano, G.; Matsumura, Y.; Adams, M.D.; Bradford, P.; Motyl, M.; Chen, L.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Pitout, J.D.D. Genomic epidemiology of global carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter spp. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Chavda, K.D.; Pandey, R.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Tang, Y.-W.; Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Du, H. Genomic Characterization of Enterobacter cloacae Isolates from China That Coproduce KPC-3 and NDM-1 Carbapenemases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2519–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuzon, G.; Bogaerts, P.; Bauraing, C.; Huang, T.D.; Bonnin, R.A.; Glupczynski, Y.; Naas, T. Spread of plasmids carrying multiple GES variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5040–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hargreaves, M.L.; Shaw, K.M.; Dobbins, G.; Vagnone, P.M.S.; Harper, J.E.; Boxrud, D.; Lynfield, R.; Aziz, M.; Price, L.B.; Silverstein, K.A.T.; et al. Clonal dissemination of Enterobacter cloacae harboring blaKPC-3 in the upper midwestern United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7723–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poirel, L.; Carrër, A.; Pitout, J.D.; Nordmann, P. Integron mobilization unit as a source of mobility of antibiotic resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2492–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kopotsa, K.; Osei Sekyere, J.; Mbelle, N.M. Plasmid Evolution in Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: A Review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.M. Integrons and gene cassettes: Hotspots of diversity in bacterial genomes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1267, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhas, M.; Van Der Meer, J.R.; Gaillard, M.; Harding, R.M.; Hood, D.W.; Crook, D.W. Genomic islands: Tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spences, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; Yu, L.F.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism mcr-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA Sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematic; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, C.; Lee, M.D.; Sanchez, S.; Hudson, C.; Phillips, B.; Register, B.; Grady, M.; Liebert, C.; Summers, A.O.; White, D.G.; et al. Incidence of class 1 and 2 integrases in clinical and commensal bacteria from livestock, companion animals, and exotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Versalovic, J.; Schneider, M.; de Brujin, F.J.; Lupski, J.R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Method Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 5, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).