Relationship between Punitive Discipline and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Moderating Role of the Context and Implementation of Parenting Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- To analyze the relationship between PD and CPV toward the father and mother.

- (2)

- To examine the moderating role of the parental context (parental stress and ineffectiveness) and the mode of implementation of parental discipline (impulsivity and parental warmth/support), as well as the gender of the aggressor, in the relationship between PD and CPV toward the father and mother.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Design and Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holt, A. Adolescent-to-Parent Abuse as a Form of “Domestic Violence”: A Conceptual Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 17, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, B. Parent Abuse: The Abuse of Parents by Their Teenage Children; Family Violence Prevention Unit, Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.; Rottem, N. It All Starts at Home: Male Adolescent Violence to Mothers; Research report Australia; Inner Couth Community Health Service Inc. and Child Abuse Research Australia, Monash University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Molla-Esparza, C.; Aroca-Montolío, C. Menores Que Maltratan a Sus Progenitores: Definición Integral y Su Ciclo de Violencia [Children violence towards parents: An integral definition and their violence cycle]. Anu. Psicol. Juríd. 2018, 28, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beckmann, L.; Bergmann, M.C.; Fischer, F.; Mößle, T. Risk and Protective Factors of Child-to-Parent Violence: A Comparison Between Physical and Verbal Aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP1309–NP1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Simmons, M. Editorial: Child-to-Parent Violence: Challenges and Perspectives in Current Society. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibabe, I.; Arnoso, A.; Elgorriaga, E. Child-to-Parent Violence as an Intervening Variable in the Relationship between Inter-Parental Violence Exposure and Dating Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, M.; McEwan, T.E.; Purcell, R. A Social-Cognitive Investigation of Young Adults Who Abuse Their Parents. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP327–NP349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, M.C.; León, S.P.; Contreras, L. Child-to-Parent Violence: Examining the Frequency and Reasons in Spanish Youth. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 1132–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Jaureguizar, J.; Almendros, C.; Carrobles, J.A. Estilos de Socializacion Familiar y Violencia de Hijos a Padres En Poblacion Espanola [Parenting styles and child to parent violence in Spanish population]. Psicol. Conduct. 2012, 20, 585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J.; Bell, T.; Fréchette, S.; Romano, E. Child-to-Parent Violence: Frequency and Family Correlates. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.; McEwan, T.E.; Purcell, R.; Ogloff, J.R.P. Sixty Years of Child-to-Parent Abuse Research: What We Know and Where to Go. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 38, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Navas-Martínez, M.J.; Contreras, L. Child-to-Parent Violence during Confinement Due to COVID-19: Relationship with Other Forms of Family Violence and Psychosocial Stressors in Spanish Youth. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, L.; León, S.P.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Socio-Cognitive Variables Involved in the Relationship between Violence Exposure at Home and Child-to-Parent Violence. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Child-to-Parent Violence: The Role of Exposure to Violence and Its Relationship to Social-Cognitive Processing. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2016, 8, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, A.; Martín, A.M.; Hess-Medler, S.; García-García, J. What Goes on in This House Do Not Stay in This House: Family Variables Related to Adolescent-to-Parent Offenses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, M.J.; Bartholomew, K.; Henderson, A.J.Z.; Trinke, S.J. The Intergenerational Transmission of Relationship Violence. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCloskey, L.A.; Lichter, E.L. The Contribution of Marital Violence to Adolescent Aggression Across Different Relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, S.M.; Rosen, K.H.; Middleton, K.A.; Busch, A.L.; Lundeberg, K.; Carlton, R.P. The Intergenerational Transmission of Spouse Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Calvete, E. Violencia filio-parental y su asociación con la exposición a la violencia marital y la agresión de padres a hijos [Child-to-parent violence and its association with exposure to marital violence and parent-to-child violence]. Psicothema 2012, 24, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, R.; Novo, M.; Fariña, F.; Arce, R. Child-to-Parent Violence and Parent-to-Child Violence: A Meta-Analytic Review. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2019, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flouri, E.; Ioakeimidi, S.; Midouhas, E.; Ploubidis, G.B. Maternal Psychological Distress and Child Decision-Making. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, M.J.; Nicklas, E.; Waldfogel, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Corporal Punishment and Child Behavioural and Cognitive Outcomes through 5 Years of Age: Evidence from a Contemporary Urban Birth Cohort Study. Infant Child Dev. 2012, 21, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLoyd, V.C.; Smith, J. Physical Discipline and Behavior Problems in African American, European American, and Hispanic Children: Emotional Support as a Moderator. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of Parenting Dimensions and Styles with Externalizing Problems of Children and Adolescents: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumrind, D. The Discipline Controversy Revisited. Fam. Relat. 1996, 45, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.F.; Hart, C.H. Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Practices: Development of a New Measure. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M.A.; Fauchier, A. Manual for the Dimensions of Discipline Inventory (DDI); Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Calvete, E. Corporal Punishment by Parents and Child-to-Parent Aggression in Spanish Adolescents. An. Psicol. 2017, 34, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoyo-Bilbao, J.D.; Orue, I.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Calvete, E. Multivariate Models of Child-to-Mother Violence and Child-to-Father Violence among Adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2019, 12, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pagani, L.; Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.; Zoccolillo, M.; Vitaro, F.; McDuff, P. Risk Factor Models for Adolescent Verbal and Physical Aggression Toward Fathers. J. Fam. Violence 2009, 24, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F.; Farrington, D.P. Direct Protective and Buffering Protective Factors in the Development of Youth Violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S8–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D.P. Explaining and preventing crime: The globalization of knowledge-the american society of criminology 1999 presidential address. Criminology 2000, 38, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. The Determinants of Parenting Behavior. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1992, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster-Stratton, C. Stress: A Potential Disruptor of Parent Perceptions and Family Interactions. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1990, 19, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J.S. Social Information Processing in High-Risk and Physically Abusive Parents. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopke, C.A.; Lundahl, B.W.; Dunsterville, E.; Lovejoy, M.C. Interpretations of Child Compliance in Individuals at High- and Low-Risk for Child Physical Abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.L.; Behl, L.E. Relationships among Parental Beliefs in Corporal Punishment, Reported Stress, and Physical Child Abuse Potential. Child Abus. Negl. 2001, 25, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Lansford, J.E.; Dodge, K.A.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E. The Development of Attitudes about Physical Punishment: An 8-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aroca-Montolío, C.; Lorenzo-Moledo, M.; Miró-Pérez, C. La Violencia Filio-Parental: Un Análisis de Sus Claves [Violence against parents: Key factors analysis]. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brezina, T. Teenage Violence Toward Parents as an Adaptation to Family Strain: Evidence from a National Survey of Male Adolescents. Youth Soc. 1999, 30, 416–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, B.; Monk, P. Adolescent-to-Parent Abuse: A Qualitative Overview of Common Themes. J. Fam. Issues 2004, 25, 1072–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennair, N.; Mellor, D. Parent Abuse: A Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2007, 38, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Kazdin, A.E. Parent-Directed Physical Aggression by Clinic-Referred Youths. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2002, 31, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. The Discipline Encounter: Contemporary Issues. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1997, 2, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.J.; Patterson, G.R. Individual Differences in Social Aggression: A Test of a Reinforcement Model of Socialization in the Natural Environment. Behav. Ther. 1995, 26, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.; Cramer, A.; Afrank, J.; Patterson, G.R. The Contributions of Ineffective Discipline and Parental Hostile Attributions of Child Misbehavior to the Development of Conduct Problems at Home and School. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Chamberlain, P.; Patterson, G.R. Ineffective Discipline and Conduct Problems in Males: Association, Late Adolescent Outcomes, and Prevention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1997, 2, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.; Morse, M.; Pastuszak, J. Effective and Ineffective Parenting: Associations With Psychological Adjustment in Emerging Adults. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 1203–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Patterson, G.R. Toward a Comprehensive Model of Antisocial Development: A Dynamic Systems Approach. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; del Hoyo-Bilbao, J.; de Arroyabe, E.L. Child-to-Parent Violence: An Exploratory Study of the Roles of Family Violence and Parental Discipline Through the Stories Told by Spanish Children and Their Parents. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus, M.A.; Mouradian, V.E. Impulsive Corporal Punishment by Mothers and Antisocial Behavior and Impulsiveness of Children. Behav. Sci. Law 1998, 16, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting Style as Context: An Integrative Model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipwell, A.; Keenan, K.; Kasza, K.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Bean, T. Reciprocal Influences Between Girls’ Conduct Problems and Depression, and Parental Punishment and Warmth: A Six Year Prospective Analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, E.A.; Bierman, K.L.; McMahon, R.J.; Lengua, L.J. Parenting Practices and Child Disruptive Behavior Problems in Early Elementary School. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2000, 29, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin Williams, L.; Degnan, K.A.; Perez-Edgar, K.E.; Henderson, H.A.; Rubin, K.H.; Pine, D.S.; Steinberg, L.; Fox, N.A. Impact of Behavioral Inhibition and Parenting Style on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems from Early Childhood through Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Contreras, L.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Family Profile of Young Offenders Who Abuse Their Parents: A Comparison With General Offenders and Non-Offenders. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, M.C.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; León, S.P.; Contreras, L. Analyzing the Relationship Between Child-to-Parent Violence and Perceived Parental Warmth. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Straus, M.A.; Carrobles, J.A.; Muñoz-Rivas, M.J.; Almendros, C. Corporal Punishment and Long-Term Behavior Problems: The Moderating Role of Positive Parenting and Psychological Aggression. Psicothema 2010, 22, 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, L. Family Relationships as Risks and Buffers in the Link between Parent-to-Child Physical Violence and Adolescent-to-Parent Physical Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 35, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Kenny, S. Longitudinal Links Between Fathers’ and Mothers’ Harsh Verbal Discipline and Adolescents’ Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larzelere, R.E. Child outcomes of nonabusive and customary physical punishment by parents: An updated literature review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 3, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripoll-Núñez, K.J.; Rohner, R.P. Corporal Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective: Directions for a Research Agenda. Cross-Cult. Res. 2006, 40, 220–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Ivy, L.; Petrill, S.A. Maternal Warmth Moderates the Link Between Physical Punishment and Child Externalizing Problems: A Parent—Offspring Behavior Genetic Analysis. Parenting 2006, 6, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germán, M.; Gonzales, N.A.; Bonds McClain, D.; Dumka, L.; Millsap, R. Maternal Warmth Moderates the Link between Harsh Discipline and Later Externalizing Behaviors for Mexican American Adolescents. Parenting 2013, 13, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, L.; Roland, E.; Coffelt, N.; Olson, A.L.; Forehand, R.; Massari, C.; Jones, D.; Gaffney, C.A.; Zens, M.S. Harsh Discipline and Child Problem Behaviors: The Roles of Positive Parenting and Gender. J. Fam. Violence 2007, 22, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Sharma, C.; Malone, P.S.; Woodlief, D.; Dodge, K.A.; Oburu, P.; Pastorelli, C.; Skinner, A.T.; Sorbring, E.; Tapanya, S.; et al. Corporal Punishment, Maternal Warmth, and Child Adjustment: A Longitudinal Study in Eight Countries. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonas, M.R.L.; Alampay, L.P. The Moderating Role of Parental Warmth on the Relation Between Verbal Punishment and Child Problem Behaviors for Same-Sex and Cross-Sex Parent-Child Groups. Philipp. J. Psychol. 2015, 48, 115–152. [Google Scholar]

- Danzig, A.P.; Dyson, M.W.; Olino, T.M.; Laptook, R.S.; Klein, D.N. Positive Parenting Interacts With Child Temperament and Negative Parenting to Predict Children’s Socially Appropriate Behavior. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 34, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Montero, I.; León, O. A Guide for Naming Research Studies in Psychology. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2007, 7, 847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in RJ Stat. Software 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The jamovi project. jamovi (Version 2.2); [Computer Software]. Available online: https://jamovi.org (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Ulman, A.; Straus, M.A. Violence by Children Against Mothers in Relation to Violence Between Parents and Corporal Punishment by Parents. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2003, 34, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersky, J.P.; Topitzes, J.; Reynolds, A.J. Unsafe at Any Age: Linking Childhood and Adolescent Maltreatment to Delinquency and Crime. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2012, 49, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Bertino, L.; Gonzalez, Z.; Montes, Y.; Padilla, P.; Pereira, R. Child-to-Parent Violence in Adolescents: The Perspectives of the Parents, Children, and Professionals in a Sample of Spanish Focus Group Participants. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, A.; Calvete, E.; Hankin, B.L. Punitive Parenting Style and Psychological Problems in Childhood: The Moderating Role of Warmth and Temperament. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, J.; Rutter, M. Validity of Adult Retrospective Reports of Adverse Childhood Experiences: Review of the Evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 95% CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

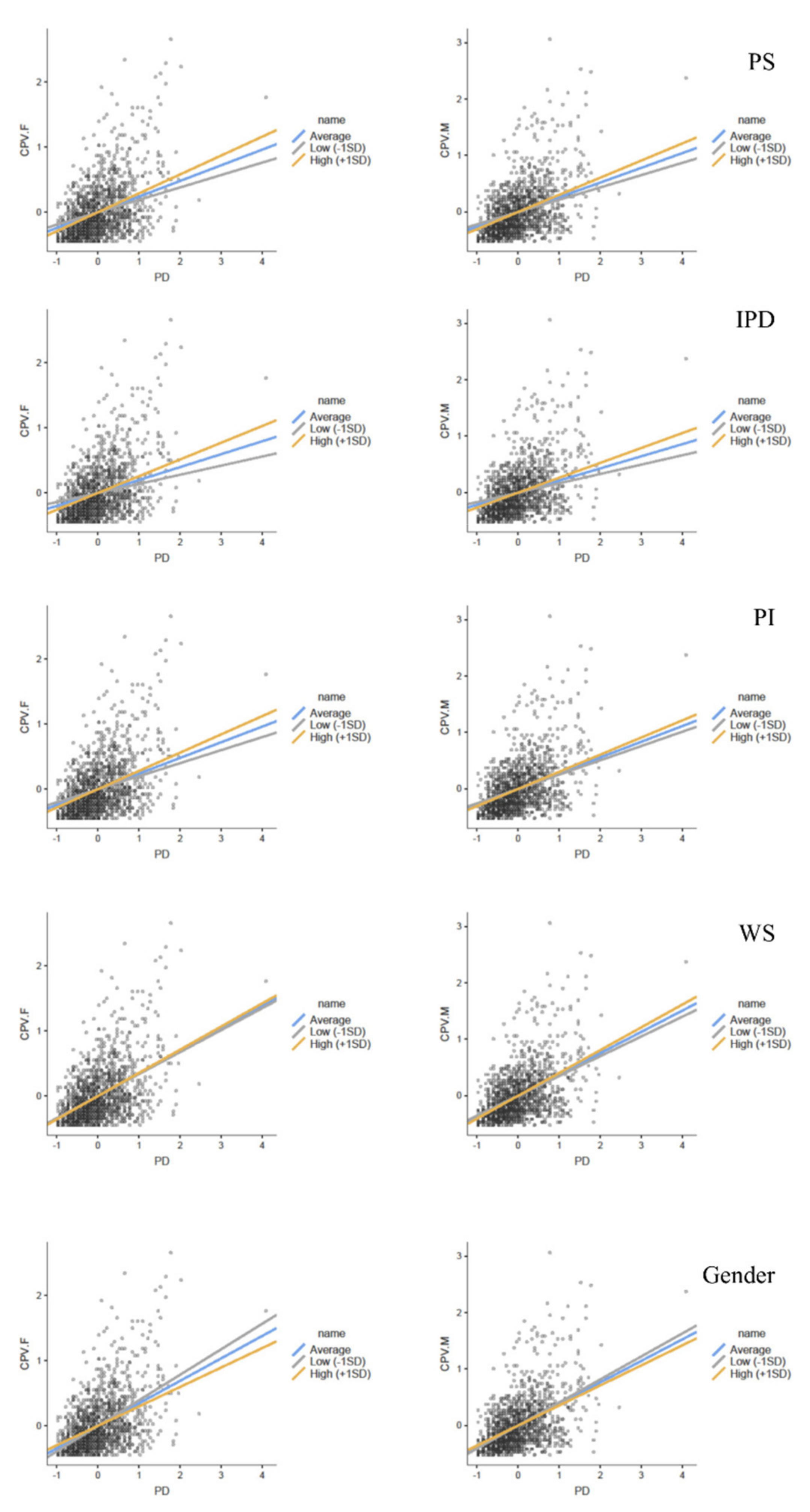

| VD | Moderator | Simple Slope | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p |

| CPV-F | PS | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 3.68 | < 0.001 | |

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 7.41 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 16.71 | < 0.001 | ||

| IPD | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 4.92 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 6.00 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 15.75 | < 0.001 | ||

| PI | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 2.99 | 0.003 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 7.35 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 16.75 | < 0.001 | ||

| WS | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.534 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 17.21 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 14.46 | < 0.001 | ||

| Gender | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.16 | −0.03 | −2.87 | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 17.39 | < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 12.70 | < 0.001 | ||

| CPV-M | PS | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 2.98 | 0.003 | |

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 7.93 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 16.48 | < 0.001 | ||

| IPD | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 3.91 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 6.74 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 15.36 | < 0.001 | ||

| PI | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.06 | 1.74 | 0.081 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 8.69 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 16.97 | < 0.001 | ||

| WS | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.534 | ||

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 17.21 | < 0.001 | ||

| High (+1 SD) | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 14.46 | < 0.001 | ||

| Gender | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.02 | −1.51 | 0.131 | ||

| Male | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 16.91 | < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 14.13 | < 0.001 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cano-Lozano, M.C.; León, S.P.; Contreras, L. Relationship between Punitive Discipline and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Moderating Role of the Context and Implementation of Parenting Practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010182

Cano-Lozano MC, León SP, Contreras L. Relationship between Punitive Discipline and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Moderating Role of the Context and Implementation of Parenting Practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleCano-Lozano, M. Carmen, Samuel P. León, and Lourdes Contreras. 2022. "Relationship between Punitive Discipline and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Moderating Role of the Context and Implementation of Parenting Practices" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010182

APA StyleCano-Lozano, M. C., León, S. P., & Contreras, L. (2022). Relationship between Punitive Discipline and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Moderating Role of the Context and Implementation of Parenting Practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010182