Abstract

Time-out is a component of many evidence-based parent training programmes for the treatment of childhood conduct problems. Existing comprehensive reviews suggest that time-out is both safe and effective when used predictably, infrequently, calmly and as one component of a collection of parenting strategies—i.e., when utilised in the manner advocated by most parent training programmes. However, this research evidence has been largely oriented towards the academic community and is often in conflict with the widespread misinformation about time-out within communities of parents, and within groups of treatment practitioners. This dissonance has the potential to undermine the dissemination and implementation of an effective suite of treatments for common and disabling childhood conditions. The parent-practitioner relationship is integral to the success of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), an evidence-based treatment which involves live coaching of parent(s) with their young child(ren). Yet this relationship, and practitioner perspectives, attitudes and values as they relate to time-out, are often overlooked. This practitioner review explores the dynamics of the parent-practitioner relationship as they apply to the teaching and coaching of time-out to parents. It also acknowledges factors within the clinical setting that impact on time-out’s use, such as the views of administrators and professional colleagues. The paper is oriented toward practitioners of PCIT but is of relevance to all providers of parent training interventions for young children.

1. Introduction

Parent training—also known as Behavioural Parent Training or Parent Management Training—is a term used to describe an empirically sound suite of programmes for the treatment of childhood conduct problems and other childhood psychopathology [1]. Internationally, childhood conduct problems represent one of the most common mental disorders diagnosed in children under seven years [2] and if left untreated, may persist into adulthood with widespread social and economic consequences [3]. Parent training has a more extensive evidence base than any other psychosocial treatment for any disorder in the child mental health context [1]. Prominent examples include the Community Parent Education Program (COPE; [4]), Defiant Children [5], Helping the Noncompliant Child [6], The Incredible Years [7], Triple P [8], and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy ([PCIT; [9]). These programmes are drawn from the work of Constance Hanf and Gerald Patterson in the 1960s and involve two phases—initially strengthening the parent-child relationship through child-led play, and later providing parents with support to have developmentally appropriate expectations of children and manage their children’s challenging behaviour safely and effectively [10,11]. Within Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), these phases are known as Child Directed Interaction (CDI) and Parent Directed Interaction (PDI), respectively.

Time-out (technically, time-out from positive reinforcement) involves a brief pre-planned withdrawal of parental attention (typically while the parent remains in the room) and restriction of access to desirable items such as toys, in response to a child’s defiance or non-compliance with a parent’s clear and fair instruction. It is incorporated in the second phase of almost all of the prominent, evidence-based parent training interventions. The intention of these programmes is to equip parents with a range of techniques or strategies to respond to children’s non-compliance or defiance in a safe and effective way. Within these parent training interventions, time-out is introduced alongside teaching parents how to give effective, developmentally sensitive commands; how to use planned ignoring in conjunction with praising the ‘positive opposite’ of an undesirable behaviour; using natural or logical consequences, and other developmentally appropriate ways of responding to a child’s non-compliance or defiance [9]. As such, time-out is one component of a collection of behaviour management strategies, which are predicated on initially strengthening and consolidating the parent-child relationship [12].

Of all of the components that make up parent training programmes, time-out is perhaps the technique that is the most well studied [13]. It appears to be particularly important for parent training programmes that are treating emerging and/or established child conduct problems (as opposed to general parenting advice aimed at preventing difficulties from occurring) [14]. Several recent reviews provide a useful and comprehensive overview of the empirical literature on time-out [12,15,16,17], including observation that “there is no empirical evidence for iatrogenic or harmful effects of time-out” [13].

Yet despite this empirical evidence of time-out’s safety when used appropriately, the strategy remains one of the more divisive and technically challenging parenting techniques. In recent years there has been growing public concern around the safety and appropriateness of time-out [12,18], fuelled by articles in popular press publications and online material; these claims have been described as “wild and unsubstantiated, yet highly visible” [19].

1.1. Aims and Scope of This Review

The intention of this practitioner review is not to replicate recent reviews of the empirical literature, nor to present a ‘how to’ guide to using time-out. These are available in the aforementioned published reviews and in treatment protocols, respectively. Rather, the intention is to consider the milieu within which time-out is situated in the clinical or treatment setting, and to highlight aspects of the literature that are of relevance to providers—a style of review which has been described as a practitioner review elsewhere e.g., [20]. It is a targeted review of the literature, that is intended to be informative and accessible, rather than an exhaustive synthesis. It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this style of review, which is not systematic and does not critically appraise the quality of the research literature relating to time-out, and therefore should not be considered a definitive summary. Given that several recent high-quality reviews relating to time-out have been conducted, this paper aims to distil and apply these findings to the clinical context, with specific reference to time-out within PCIT. It aims to make the research literature accessible to and engaging for practitioners. It ultimately aims to consider how practitioners might maintain delivery of, and advocacy for this well-studied component of parent training, in the context of public concern.

1.2. Structure of the Review

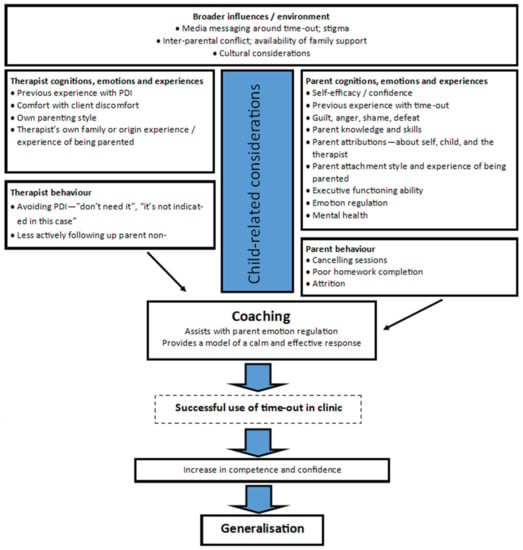

Therapists charged with delivery of parent training approaches that include time-out benefit from an awareness of the broader context, including parents’ beliefs and preferences [18]. The review begins with an overview of these wider influences. In clinical settings, time-out is typically introduced, taught, and—within PCIT—coached in the context of a therapeutic relationship between a parent (or caregiver) and practitioner. As such, the review goes on to explore both therapist and parent cognitions, emotions and behaviour, and how these inter-relate. The therapeutic coaching relationship, and the role and influence of factors such as practitioner attitudes toward time-out, transference and counter-transference, and how these elements might influence parents’ ability and willingness to use time-out is also considered. Finally, the review concludes with a series of specific sections relating to (1) Child-related considerations, (2) Addressing specific parent concerns (including the use of ‘time-in’) and (3) Addressing concerns from colleagues or administrators (including a comment on seclusion). The structure of the review is represented in Figure 1. The discussion is oriented around PCIT, though is relevant to providers of other parent training programmes.

Figure 1.

Summary of parent-practitioner related considerations.

2. Broader Influences/Environment

“[My mother], she’d read a book and she had an idea that… putting Emma on the time-out chair wasn’t a good idea… so there was a real… disorder between the PCIT and at home...” [21].

Outside of the therapy room, there are a number of influences that may shape the lens through which a parent views time-out. A parent is typically a member of a number of different systems or groups, which may have mixed or disparate views on time-out—for example, extended family, social groups, childcare centres or antenatal groups. Parental stress levels, socioeconomic factors, and the extent of wider family support (including the degree of unity or conflict between parents) are influential on engagement generally [22], and potentially on the acceptability of time-out specifically.

Cultural factors are also very relevant, as these may influence gender roles, parenting styles, and parent engagement in treatment programmes [23]. The research literature relating to the acceptability of time-out to parents (and children) of minority ethnicities is limited [24]. Reviews that have been published have tended to explore the interaction between majority cultural groups and parent training programmes generally [17], or the international transportability of programmes, i.e., whether the programme is still effective when introduced to a different country (e.g., [25]). Relevant to time-out is the extent to which particular cultural beliefs value interdependence, hold that a parent ought to or should assume control of/‘take charge’ of a child’s behaviour, demonstrate affection, and the parent’s level of comfort with limit setting [17].

Often, parent training approaches include techniques that have been developed and normed within an Anglo-American cultural context in the United States [17,24]. This somewhat individualistic (vs. collectivistic) cultural context often values parental control, but also allows for the child to negotiate or reason with their parent, i.e., also values the child’s autonomy and individual freedom [17,24]. If this cultural group is assumed to be the “default”, the advice drawn from parent training programmes may be viewed with distrust by parents from minority cultures, and there may be a dissonance with parent attitudes and beliefs in the diverse real world of service delivery [24]. Future research ought to consider the influence of more precise factors such as families’ acculturation, immigration experiences, and socioeconomic status [24]. Ideally, practitioners ought to facilitate discussion around the family’s religion, family traditions, parents’ own experiences of having been parented [24], and explore how time-out ‘sits with’ the family in relation to their cultural values [17].

Media messaging and public and professional dialogue conspicuously feature two inter-related concerns about time-out, namely, that it (1) causes harm in otherwise healthy children, and that it (2) exacerbates existing difficulties in children who have experienced trauma, despite evidence to the contrary on both counts [12]. Parents are beginning to echo and amplify high-profile media criticisms of time-out, contributing to perception that it is ineffective and harmful [18]. In the clinical context, understanding and addressing parental concerns is essential, as—in terms of parent engagement—the empirical evidence relating to whether time-out causes harm is perhaps less relevant than a parent’s concern that it might. Even where parents are weary or ambivalent, fearful of (or angry at) their child, they typically want to do what is best for their child. The therapist-parent relationship is an essential vehicle for validation of parents’ emotion, and an opportunity to provide brief tailored support for the parent as they navigate the often-wide-ranging views and perspectives of the people in their world.

3. Therapist Cognitions, Emotions, Experiences and Behaviour

“I come from an attachment framework and struggle with some of the aspects of PCIT” (PCIT Practitioner) [26].

Unless a treatment programme is delivered by way of pre-recorded material (for example, Triple P Online [27]), time-out is typically introduced in the context of a practitioner-parent relationship. A practitioner’s experience with teaching and coaching time-out, the nature of their relationship with the parent and child, and their own level of comfort with client discomfort (in the service of greater goals) may influence their willingness to implement time-out in PCIT. Factors such as the practitioner’s own family of origin experiences (i.e., experience of having been parented) and their own parenting practice (i.e., use of, and attitudes toward time-out with their own children) may also be relevant. Practitioners may underestimate the influence of their own emotional state—perhaps ambivalence or wariness relating to time-out—on their behaviour in session. This is a cognitive bias known as the hot-cold empathy gap that is increasingly considered relevant to the implementation of psychosocial interventions [28]. This dynamic is apparent in another treatment, namely exposure-based tasks within Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for anxiety disorders. Relative to other techniques, exposure tasks tend to be infrequently used by clinicians, with Deacon and Farrell [29] suggesting that this cannot be explained by dissemination difficulties alone. Instead, they propose that “negative beliefs about exposure therapy (e.g., that it is unethical, intolerable and unsafe) impede the utilization of this treatment, even among therapists trained to administer it” [29].

A particular transferential dynamic can evolve in the parent-therapist relationship when a parent raises concerns around time-out. Hawes and Dadds [30] describe this as “the spread of anxiety or pessimism from parent to therapist” (p. 6). Therapists themselves may be somewhat ambivalent about time-out [26], or perhaps anxious about their ability to successfully coach a parent through the early PDI sessions, which can be complex and demanding to facilitate. The therapist may inadvertently conceptualise the parent’s position as resistant, or unconsciously form a rationale for omitting PDI from the PCIT protocol (e.g., that the child’s behaviour has improved substantially in CDI, so PDI is unnecessary), thereby “inadvertently collud[ing] to avoid strategies that require parents to set limits on misbehaviour” [30]. Recognising and becoming aware of these dynamics is an essential step in addressing these common “signs of a struggle for change” [30].

The early attachment experiences of both the therapist and the parent may manifest in the therapeutic relationship during the course of a parent training intervention. Core sensitivities are internal working models, anxieties or considerations that an individual holds in relation to their role in connection with others [31,32]. While these dynamics are primarily conceptual rather than empirical, they can be useful in assisting with understanding a particular pattern of connection between therapist and parent. For example, an esteem sensitive parent may strive to demonstrate success or achievement (e.g., with homework completion) and may be very vigilant and sensitive around criticism (e.g., in coaching, which is typically more directive in PDI) [32]. A separation sensitive parent may experience limit setting as conflict, which is potentially associated with separation [31]—for this parent, taking charge during the PDI phase of PCIT may be particularly challenging and require additional therapist support. At its best, the parent-practitioner relationship can provide a safe haven and secure base for the parent, and a model of what “bigger, stronger, wiser and kind” looks and feels like to a child [32].

4. Parent Cognitions, Emotions, Experiences and Behaviour

“…while [PDI sessions] were horrible sessions, in many regards, they were the most valuable sessions because it taught me what I could do with him under many situations and recover the situation and not let my child ruin my life. And not let him have… parents that didn’t like him” [21].

In recent years, and in the context of increased media and public concerns relating to time-out, three studies have investigated parents’ understanding of time-out [33,34,35]. Findings across all three studies demonstrated that parents’ understanding of the purpose and procedure for time-out differed from the empirical literature. The majority of parents perceived time-out as a time for their children to “think” [34] “think about bad behavior” [35], or “think about what they had done” [33]. This is in contrast to the theoretical rationale for time-out, i.e., to remove the child from a reinforcing environment following misbehaviour [12]. Beyond their technical understanding of the time-out process, a parent’s acceptance of a discipline technique such as time-out includes measures of their willingness to use it with their own child, anticipated disruption of implementing the discipline, perceived effectiveness of the technique, and expectation that using the discipline would lead to improvement in their child’s behaviour [36]. Parents who reported using time-out with their 1-to 10-year-old children and rated it as being effective were significantly more likely to report using empirically supported time-out steps [35]. Also, expected relationships emerged between parents’ understanding about time-out, their use of time-out with their own child, and their acceptance of the technique [33]. Parents who endorsed accurate knowledge about time-out rated an evidence-based description of time-out as more acceptable than parents who endorsed less accurate knowledge. In contrast, parents who endorsed more negative attitudes and beliefs about time-out perceived an evidence-based description of time-out as less acceptable than parents who endorsed fewer negative attitudes. Beyond ratings of acceptability, parents’ accurate understanding as well as negative attitudes and beliefs about time-out were significantly associated with their use of empirically supported time-out steps. Parents who agreed with accurate beliefs about the safety and effectiveness of time-out were more likely to report using a greater number of evidence-based time-out steps when using time-out with their children. In contrast, parents who indicated holding more negative attitudes toward time-out were more likely to report using fewer evidence-based time-out steps [33].

This interplay of parents’ experience using time-out with their children, their understanding about time-out, and their perceptions of the effectiveness of time-out are likely all coming into the treatment room when they meet with the therapist. The parent may also be experiencing feelings of inadequacy, overwhelm or anxiety, anger, guilt or shame from a ‘history of 10,000 defeats’ in disciplinary interactions with their child [37].

Time-out is first mentioned early in the course of PCIT in the intake assessment, where therapists are encouraged to “ask specifically” about a parent’s use of timeout [9], p. 11. In our experience, parents often respond with words to the effect of “I’ve tried time-out, but it didn’t work”. A distinction may be drawn between a parent’s experience of time-out having been ineffective, and their perception that it would be ineffective for their child. Each of these scenarios might require a tailored response from the PCIT therapist, as described below.

For example, prior to using time-out, a parent might form an impression or perception that time-out would be ineffective for their child, perhaps partly as a result of their child-referent attributions or cognitions around the cause of their child’s disruptive behaviour. These causal explanations for a child’s challenging behaviour and cognitions about their parenting role, that parents form implicitly or explicitly may influence how parents engage with parent training and may predict attrition from treatment [38,39,40]. For example, if a parent’s attributions suggest that the cause of the child’s difficulties is internal to the child and stable, this is likely to influence their willingness to consider changing their own behaviour and engaging with a technique such as time-out—stated plainly, there may be an immediate sense of “that won’t work—he’s a bad kid”. The parent may form the impression that time-out is not novel, sophisticated or salient enough to change the behaviour of a child who is perceived to be manipulative, vindictive or deviant. In response, the PCIT therapist might name or describe the apparent dissonance between a parent’s sense of what the child needs and what PCIT is advocating and spend more time explaining the rationale.

As outlined earlier, it is also possible that a parent has experienced time-out as ineffective in the past, as it can be difficult to implement correctly [13]. Time-out is not one technique, but a series of steps, that are ideally implemented sequentially and in a pre-determined order (refer to Table 1 for these components and their associated evidence and the Supplementary Material for a case vignette). Omitting or substituting one or more components of the time-out process or applying time-out inconsistently, may inadvertently worsen a child’s disruptive behaviour [41], potentially discouraging a parent from using time-out again, and fostering a perception that it is ineffective.

Table 1.

Time-out components and their associated rationale.

Often, the parent comes to PCIT having inadvertently established a pattern where aversive discipline interactions with their child are occurring regularly and are rich in content which relates to basic attachment needs in the child [61]. Positive parent-child interactions have become less frequent and typically have become “attachment neutral” [61]. If reward strategies such as star charts or labelled praise are infrequent and ‘neutral’, and discipline interactions are frequent and ‘rich’, it is easy to see why a parent might perceive that time-out is ineffective [61]. Time-out may remain “subtly infused with attachment-rich behaviours (e.g., hostility, rejection, ambivalence) that are highly salient and threatening to the child” [61]. Successful use of time-out depends on the parent shifting the balance, to ensure that positive or neutral time with their child is richer (from an attachment perspective) than disciplinary exchanges. Therapist coaching in PCIT is particularly well placed to ensure this occurs – the coach may encourage the parent to use positive voice tone, physical touch, eye contact, and expressions of enjoyment in both CDI and PDI.

5. Coaching Time-Out

“[The coaches] talked me through it very calmly, just with their calmness of their voice, sticking to the plan, and I guess as outsiders and probably that division of the glass as the outsiders looking in, they’re not in the heat of the moment, and so they talked me through the heat of the moment… what would have been impossible at home” [21].

The decision that a parent makes, in the moment, of which strategy to use in response to their child’s challenging behaviour is often instinctive, rather than intellectual. Many parents are able to describe the optimal response to a child’s behaviour hypothetically, however ‘real world’ parenting behaviour involves the interaction of a number of complex processes. These include a parent regulating their arousal levels and emotions and demonstrating inhibition and self-control [38,40]. These processes are particularly relevant to the PDI phase, and specifically to the use of time-out, as disciplinary exchanges can be provocative for parents [62]. PCIT and other programmes that include in vivo coaching of parents with their child offer a distinctive opportunity to rehearse and consolidate alternative responses, alongside the coach who provides social modelling of a calm and effective response [21]. With repetition, a process of ‘overlearning’ occurs, facilitating the easier recall and use of the strategy when required in the real world [63]. As such, coaching is important for parent skill acquisition [64], but it appears to serve a number of additional functions for the parent. For example, recent research with child welfare-involved families suggests that PCIT supports the development of parents’ inhibitory control and emotion regulation abilities, and the softening of negative attributions about their child [40]. A recent paper proposes a model of how this change comes about, with parent coaching as a central mechanism of change, including suggestions that the PCIT coach provides “real time regulatory support” for the parent [65].

All coaching is not created equal, however. Directive techniques (i.e., telling the parent what to do) may inadvertently contribute to parent resistance; alternatively, responsive coaching appears to be particularly useful for parents’ skill acquisition and engagement [66]. Positive, responsive coaching reinforces parents’ use of a particular technique or interaction with their child [66]. Examples of responsive coaching techniques include providing labelled or unlabelled praise for parents’ behaviour or interactions with their child or linking the child’s behaviour to the parents’ use of skills [66]. The PCIT coach can also subtly interrupt a parent’s harsh response, and a potentially coercive parent-child exchange, and support the parent to generate an alternative response in the moment [65].

Coaching a parent to use time-out effectively may also assist a parent who has previously felt ineffective or ill-equipped to experience a sense of mastery or competence. An anxious parent has an opportunity to be exposed, with the support of the PCIT coach, to that which they fear, i.e., their child’s defiance or non-compliance. Repeated experiences of successfully managing this process will likely build the parent’s confidence and decrease avoidance of limit-setting.

6. Child-Related Considerations

The standard PCIT time-out procedure is indicated for children with a developmental age of approximately 2.5 years and above [9]. For developmental and relational reasons, time-out is not indicated for children younger than two [67] and for practical reasons, other strategies (such as incentive systems or removal of privileges) are typically used with older children [68]. A specific adaptation has been developed for toddlers younger than 2 years old, where the follow-up after a command involves a guided compliance procedure, i.e., the parent gently guides the child in following their instruction; [67]. The adaptation assumes that toddlers have not yet achieved the required language comprehension, ability to sustain attention, and social awareness to comply with parent instructions [67]. Studies have also described adaptations to the PCIT protocol—typically for younger children—that do not involve the use of time-out, including Parent-Child Attunement Therapy [69].

Similarly, an adaptation to the standard procedure has been developed for children on the Autism Spectrum [70]. It includes a time-out readiness phase where there are concerns around the child’s language comprehension, extreme behaviours (e.g., self-injury, extreme aggression), or relating to parent reluctance to use time-out with their child with special needs [70]. The adaptation also includes a physical guidance contingency for rapidly and effectively concluding the time-out process where necessary, which the authors describe as the Big Red Stop Button [70]. These examples of adaptations acknowledge the importance of considering factors such as the child’s age, cognitive abilities, and adaptive skills.

There is little published research on the acceptability of time-out to the child, and the child’s experience of time-out. During a time-out process, children may shout, scream, hit, kick or cry, and it is often assumed that this represents a time of distress for the child—a frequently cited critique of the technique. Another possibility is that—rather than distress—the child is protesting the implementation of new limits and consequences. Learning to stay on a time-out chair as a pre-explained consequence for non-compliance with a calm, fair and reasonable command, represents a series of small and repeated challenges for the child, and this may be conceptualised as an opportunity to develop resilience and self-regulation. Also, experiencing mild or moderate, short-lived anger, frustration or anxiety may be important in helping children develop emotion and behaviour regulation skills [19]. Importantly, the child learns

“no matter how upset I am, no matter how much I cry, scream, kick, or shout curse words, I will be safe. No one will yell at me or hit me. My parents will remain regulated” [19].

For the child, time-out may represent a safer alternative than physical discipline, as a disciplinary exchange can represent a period of higher risk of physical harm for the child [40]. Unlike spanking, brief time-outs can be used several times per day initially (their required frequency would be expected to decrease rapidly if implemented correctly), which allows the parent to be more consistent in their response [68].

7. Addressing Specific Parent Concerns

If a parent raises doubts, concerns or questions about time-out, it can be useful to initially thank the parent for doing so [30]. It is possible that the parent is posing a question that can be addressed by providing specific information or recommending a resource—indeed, one of the functions of parent training programmes is to support parents to discern which skill, strategy or response is indicated in a particular scenario. Niec [19] provides a compendium of possible therapist responses to specific parent concerns.

However, oftentimes there is a deeper concern or process that might be occurring for a parent. For example, a parent asking, “What’s the evidence for time-out, anyway?” is unlikely to be requesting a precis of the latest meta-analysis but may in fact be wondering “Am I doing the right thing for my child?”. Similarly, a parent who appears resistant (perhaps by persistently replying “yes, but…”) may have a deeper need that relates more to the process of therapy, rather than the content under discussion. Naming or reframing this can be useful, as “resistance that is implicit and unspoken is at particular risk of continuing unchecked. Naming it allows the therapeutic team to examine it openly together” [30]. An example of naming this process might include “I can provide you with evidence if that would be helpful, though I wonder if perhaps you have deeper concerns about this stage of the programme”. A reflective statement, followed by a pause or silence from the therapist, can result in a parent sharing fears or concerns that can then be more usefully addressed.

Another possibility is to acknowledge the parent’s ambivalence around time-out, followed by the conjunction “and” (cf. “but”)—for example: “I’m aware that you’ve used time-out in the past and have had limited success, and I have a specific way of doing time-out to share with you that I’m confident will be effective”. This conjunction substitution is utilised in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT; [71]) and can signal that both perspectives have validity. In this case, it serves the purpose of validating the parent’s experience, while also indicating that a different experience is possible with time-out. There is growing interest in improving parent emotion regulation through integration of DBT principles within parent training [72]—as outlined earlier, this may be achieved formally, or through the naturalistic opportunities afforded by the coaching relationship between parent and therapist in PCIT [65].

There are certainly situations where time-out is not indicated and may indeed be ineffective or contraindicated. The PCIT protocol recommends time-out as a response to a child’s non-compliance with an effective command (i.e., a direct, necessary, developmentally appropriate parental instruction), and suggests that commands are to be used sparingly [9]. When a child is distressed or overwhelmed (perhaps due to an injury, tiredness or hunger), choosing not to give a command, but rather attending to the primary need, is a more suitable response than time-out. Likewise, behaviour such as whining or complaining ought to ideally be responded to with brief planned ignoring, rather than time-out [9]. Time-out is not indicated as a response to a child having a tantrum. Where a young child is struggling to regulate their emotions outside of the parent giving directions, or the child is tired or hungry, a parent providing a “time-in” (as described below) is likely to be the most appropriate response. Table 2 provides examples of how these scenarios may be differentiated. Lieneman and McNeil [17] also present a useful table to assist parents to determine whether it is an appropriate time to use a command (which may go on to require time-out if the child is non-compliant), along with a summary of alternatives to commands. They suggest that in order for a direct command to be used, a child must be well-rested, not be too hungry or thirsty, be alert, have recently used the toilet, and be ready to learn [17].

Table 2.

Examples of scenarios to demonstrate the use of “time in” and “time-out” across a spectrum of behaviour.

Time-In

Time-in is inconsistently defined in the academic literature and popular press. One understanding of time-in is aligned with a parent providing the PRIDE skills (Praise, Reflection, Imitation, behavioural Description, and Enjoyment) in the Child Directed Interaction phase of PCIT. Use of these skills is recommended any time the child is not in time-out. When a child experiences intense disappointment, anger or frustration that is not necessarily associated with aggression or destructive behaviour, sitting alongside the child and describing their experience can aid the development of their emotion regulation abilities [73]. Paired with differential attention, the parent models calmness through their tone of voice and attends to their child’s appropriate behaviour. Recognising a child’s emotion, labelling this, and validating their experience (not necessarily their actions) can enhance children’s social and emotional functioning [74].

8. Addressing Concerns from Colleagues or Administrators

“I have become uncomfortable about the use of time-out by PCIT. For the children I see with trauma histories—this is entirely inappropriate” (PCIT Practitioner) [26].

8.1. Attachment-Based Interventions

The popular perception of a dissonance between behaviourally based and attachment-based paradigms is unhelpful and underpins much of the contradictory material available to parents. In fact, the parent-child attachment relationship is the foundation upon which PCIT stands, as evidenced by CDI being central to the treatment and delivered first. In recent years, attempts have been made to bridge this divide by observing the overlap or commonalities across the two models – for example Troutman’s [75] book “Integrating Behaviorism and Attachment Theory in Parent Coaching”. In this book it is proposed that the ideal parent-child attachment relationship ought to be hierarchical and that a parent being in charge and setting limits is not mutually exclusive with an attachment-oriented approach. Troutman [75] observed that attachment theorists such as Mary Ainsworth—contrary to popular belief – have suggested that a child benefits from “learning about the limits of their power and not being able to control their parents” [75]. Although Ainsworth did observe that the child ought to first control his or her own world through parents responding to their requests [75], as is reflected in the CDI phase of PCIT. Similarly, prominent attachment author Dr Dan Siegel has actually suggested that the use of time-out is reasonable in his statement that “the “appropriate” use of time-outs calls for brief, infrequent, previously explained breaks from an interaction used as part of a thought-out parenting strategy that is followed by positive feedback and connection with a parent. This seems not only reasonable, but it is an overall approach supported by the research as helpful for many children” [76]. Unfortunately, this middle ground, which is likely to represent a position with which many experts agree, has not received the same degree of media attention as the more polarised views of time-out.

Also, perhaps rather than an attachment-focussed intervention being considered superior or inferior to a parent training programme, it may be more useful to consider timing and context. Often parents of children with conduct problems present to services for treatment when they are in crisis. At that time, they are often seeking (and treatment planning typically indicates) a series of evidence-based strategies to make daily life more manageable. Once the crisis has resolved somewhat, the parent is likely to be better able to make use of an attachment-focussed intervention that may involve enhancing reflective functioning and mentalising ability but doesn’t necessarily provide specific strategies. An example might include the Circle of Security Intervention [32], which—in keeping with the middle ground outlined above, advocates for parents to be ‘bigger, stronger, wiser and kind’.

8.2. Seclusion

Efforts are underway internationally to reduce agencies’ use of seclusion (i.e., placing and detaining an individual in a room) and restraint (i.e., confining an individual’s bodily movements) as it has been suggested that they can result in significant harm—both physical and psychological [77]. In contrast to provision of other parent training programmes where parents might be advised to rehearse using time-out in their home, PCIT presents a somewhat unique challenge to agencies in that parents are supported to place their child on a time-out chair, and—if necessary—in a time-out room for a one-minute period, on agency premises. However, several elements differentiate the use of time-out from seclusion: (1) rather than a service provider, it is the child’s parent who initiates and carries out the process, and the clinician does not implement time-out with the child; (2) the parent elects to undertake the process and may choose to end the process at any time; and (3) PCIT (and indeed other parent training programmes) include information and support for parents to discern when to use time-out, and when alternative strategies would be indicated.

The issue of agencies seeking to reduce seclusion has been identified as a barrier to implementation at a policy level in large-scale PCIT initiatives in the USA, though examples are available of contexts where difficulties were resolved by way of creating a policy clarification, providing additional education or adapting implementation [78]. In New Zealand, the Ministry of Health issued a position statement in 2019, suggesting “a clear distinction between a clinician coaching a parent to use time-out in a relationally based paradigm and a mental health service using seclusion for safe containment” [79].

9. Conclusions

Time-out is not intended to be used as a stand-alone technique in the management of children’s challenging behaviour, but rather as one component of a multi-faceted approach which includes parent-child relationship enhancement as its foundation [17,19,75]. The behaviour management phase of parent training interventions such as PCIT typically includes a variety of components, of which the correct and appropriate use of time-out is but one [17]. Parents are supported to give effective instructions, which are developmentally appropriate, calmly stated, clear, and given one at a time [9]. Importantly, parents are encouraged to use such direct commands sparingly, and to be consistent and fair both in their expectations of their child, and in their use of consequences [9].

This practitioner review, while not an exhaustive or systematic summary of the literature, has identified areas that warrant future research attention. These include a better understanding of professionals’ knowledge of, and attitudes toward time-out, and how this influences the implementation of PCIT in clinical settings. There is also a need for a careful examination of the practitioner-related factors (e.g., education, training, experience, or context) that are associated with effective and sustained implementation of parent training approaches that include time-out. And, importantly, more research into a child’s experience of time-out is also necessary.

In summary, the parent-practitioner relationship is integral to the success of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) yet this relationship, and practitioner perspectives, attitudes and values as they relate to time-out, are often overlooked. Delivering parent training interventions that include time-out can be challenging for practitioners. Misinformation abounds, the technique involves a number of steps, and coaching time-out processes in the clinic can be challenging for practitioners—both practically, and emotionally. Yet, given the effectiveness and established safety of time-out, and the potential harm associated with untreated or ineffectively treated childhood conduct problems, persisting with the delivery of evidence-based parent training programmes which include time-out is likely to result in parents being better equipped to respond to their child’s challenging behaviour effectively, sensitively and safely.

| Key Practitioner Messages |

|

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19010145/s1, Box 1: Vignette illustrating an evidence-based time-out process for non-compliance with a parent’s instruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.W. and I.B.; methodology, M.J.W., I.B. and S.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.W.; writing—review and editing, M.J.W., I.B. and S.E.H.; supervision, S.E.H.; funding acquisition, M.J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research is supported by a Clinical Research Training Fellowship for MJW from the Health Research Council (HRC) of New Zealand. SEH holds an Auckland Medical Research Foundation (AMRF) Douglas Goodfellow Repatriation Fellowship and is a Cure Kids Research Fellow. The HRC, AMRF and Cure Kids were not involved in study design or execution.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for Sally Merry’s review and insightful comments. Larissa Niec contributed to an earlier manuscript from which material is drawn for this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

M.J.W. is a Within-Agency Trainer for PCIT (though receives no additional remuneration for this role).

References

- Scott, S.; Gardner, F. Parenting programs. In Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Thapar, A., Pine, D.S., Leckman, J.F., Scott, S., Snowling, M.J., Taylor, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva, M.; Graf, R.K.; Reinelt, T.; Petermann, U.; Petermann, F. Research review: A meta-analysis of the international prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in children between 1 and 7 years. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivenbark, J.G.; Odgers, C.L.; Caspi, A.; Harrington, H.; Hogan, S.; Houts, R.M.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: Evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.; Bremner, R.; Secord-Gilbert, M. The community parent education (COPE) program: A school-based family systems oriented course for parents of children with disruptive behavior disorders. Unpublished manual. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley, R.A. Defiant Children: A Clinician’s Manual for Assessment and Parent Training; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, R.J.; Forehand, R.L. Helping the Noncompliant Child: Family-Based Treatment for Oppositional Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton, C. The Incredible Years: Parents, Teachers, and Children Training Series; Office of Juveline Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 18, pp. 31–45.

- Sanders, M.R.; Markie-Dadds, C. Triple P: A multilevel family intervention program for children with disruptive behaviour disorders. In Early Intervention & Prevention in Mental Health; Cotton, P., Jackson, H., Eds.; Australian Psychological Society: Carlton South, Australia, 1996; pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Funderburk, B. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol; PCIT International, Inc.: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaehler, L.A.; Jacobs, M.; Jones, D.J. Distilling Common History and Practice Elements to Inform Dissemination: Hanf-Model BPT Programs as an Example. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 19, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reitman, D.; McMahon, R.J. Constance “Connie” Hanf (1917–2002): The Mentor and the Model. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2013, 20, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadds, M.; Tully, L.A. What is it to discipline a child: What should it be? A reanalysis of time-out from the perspective of child mental health, attachment, and trauma. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijten, P. Effective Components of Parenting Programmes for Children’s Conduct Problems. In Family-Based Intervention for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Core Competencies Approach; Essau, C.A., Hawes, D.J., Allen, J.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Leijten, P.; Gardner, F.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; van Aar, J.; Hutchings, J.; Schulz, S.; Knerr, W.; Overbeek, G. Meta-Analyses: Key Parenting Program Components for Disruptive Child Behavior. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larzelere, R.E.; Gunnoe, M.L.; Roberts, M.W.; Lin, H.; Ferguson, C.J. Causal Evidence for Exclusively Positive Parenting and for Timeout: Rejoinder to Holden, Grogan-Kaylor, Durrant, and Gershoff (2017). Marriage Fam. Rev. 2020, 56, 287–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetsch, L.B.; Wallace, N.M.; Herschell, A.D.; McNeil, C.B. Weighing in on the Time-Out Controversy: An empirical perspective. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 68, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lieneman, C.; McNeil, C.B. Time-Out for Child Behavior Management; Volume 52, in press.

- Canning, M.G.; Jugovac, S.; Pasalich, D.S. An Updated Account on Parents’ Use of and Attitudes Towards Time-Out. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niec, L.N. When negative emotion is a positive experience: Healthy limit-setting in the parent-child relationship. In Strengthening the Parent-Child Relationship in Therapy: Laying the Foundation for Healthy Development; in press.

- Creswell, C.; Waite, P.; Hudson, J. Practitioner Review: Anxiety disorders in children and young people—Assessment and treatment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, M.J.; Cartwright, C. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy from the Parents’ Perspective. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieneman, C.C.; Quetsch, L.B.; Theodorou, L.L.; Newton, K.A.; McNeil, C.B. Reconceptualizing attrition in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: “dropouts” demonstrate impressive improvements. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forehand, R.; Kotchick, B.A. Cultural diversity: A wake-up call for parent training. Behav. Ther. 1996, 27, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenmuller, C.; Hilton, D. Barriers to access, implementation, and utilization of parenting interventions: Considerations for research and clinical applications. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F.; Montgomery, P.; Knerr, W. Transporting Evidence-Based Parenting Programs for Child Problem Behavior (Age 3–10) Between Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2016, 45, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodfield, M.J.; Cargo, T.; Barnett, D.; Lambie, I. Understanding New Zealand therapist experiences of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) training and implementation, and how these compare internationally. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.R.; Baker, S.; Turner, K.M. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of Triple P Online with parents of children with early-onset conduct problems. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidas, R.S.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Mandell, D.S. Transforming Mental Health Care Delivery Through Implementation Science and Behavioral Economics. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, B.J.; Farrell, N.R. Therapist Barriers to the Dissemination of Exposure Therapy. In Handbook of Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety Disorders; Storch, E.A., McKay, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, D.J.; Dadds, M. Practitioner Review: Parenting interventions for child conduct problems: Reconceptualising resistance to change. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, B.; Coyne, J. The core sensitivities: A clinical evolution of Masterson’s disorders of self. Psychother. Couns. J. Aust. 2017, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B.; Cooper, G.; Hoffman, K.; Marvin, B. The Circle of Security Intervention: Enhancing Attachment in Early Parent-Child Relationships; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- Brodd, I.; Niec, L.N. Parents’ Attitudes Toward Time-Out; Central Michigan University: Mount Pleasant, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Drayton, A.K.; Byrd, M.R.; Albright, J.J.; Nelson, E.M.; Andersen, M.N.; Morris, N.K. Deconstructing the time-out: What do mothers understand about a common disciplinary procedure? Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 2017, 39, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.R.; Wagner, D.V.; Tudor, M.E.; Zuckerman, K.E.; Freeman, K.A. A survey of parents’ perceptions and use of time-out compared to empirical evidence. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.L.; Heffer, R.W.; Gresham, F.M.; Elliott, S.N. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1989, 11, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R.; Chamberlain, P. A functional analysis of resistance during parent training therapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1994, 1, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Park, J.L.; Miller, N.V. Parental Cognitions: Relations to Parenting and Child Behavior. In Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan; Sanders, M.R., Morawska, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sawrikar, V.; Hawes, D.J.; Moul, C.; Dadds, M. The role of parental attributions in predicting parenting intervention outcomes in the treatment of child conduct problems. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 111, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoranski, A.M.; Skowron, E.A.; Nekkanti, A.K.; Scholtes, C.M.; Lyons, E.R.; DeGarmo, D.S. PCIT engagement and persistence among child welfare-involved families: Associations with harsh parenting, physiological reactivity, and social cognitive processes at intake. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, G.E.; Hupp, S.D.; Olmi, D.J. Time-out with parents: A descriptive analysis of 30 years of research. Educ. Treat. Child. 2010, 33, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyman, J.S.; Johnson, H.; Buie, J.D.; Nelson, C.M. The use of a warning procedure to signal a more intrusive timeout contingency. Behav. Disord. 1994, 19, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.W. The effects of warned versus unwarned time-out procedures on child noncompliance. Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 1983, 4, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H.L.; Forehand, R.; Roberts, M. Time-out with children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1976, 4, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarboro, M.E.; Forehand, R. Effects of two types of response-contingent time-out on compliance and oppositional behavior of children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1975, 19, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantner, J.P.; Doherty, M.A. A review of timeout: A conceptual and methodological analysis. In The Effects of Punishment on Human Behavior; Axelrod, S., Apsche, J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 87–132. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonough, T.S.; Forehand, R. Response-contingent time out: Important parameters in behavior modification with children. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1973, 4, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, G.A.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Manos, M.J.; Gnagy, E.M.; Chronis, A.M.; Onyango, A.N.; Lopez-Williams, A.; Burrows-MacLean, L.; Coles, E.K.; Meichenbaum, D.L.; et al. An evaluation of three time-out procedures for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, S.A.; Forehand, R. Effects of differential release from time-out on children’s deviant behavior. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1975, 6, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapalka, G.; Bryk, L. Two-to four-minute time-out is sufficient for young boys with ADHD. Early Child. Serv. 2007, 1, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin, P.W. The effect of timeout duration on frequency of aggression in hospitalized children with conduct disorders. Behav. Interv. 1991, 6, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.D.; Nielsen, G.; Johnson, S.M. Timeout duration and the suppression of deviant behavior in children. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1972, 5, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bean, A.W.; Roberts, M.W. The effect of time-out release contingencies on changes in child noncompliance. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1981, 9, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.W.; Powers, S.W. Adjusting chair timeout enforcement procedures for oppositional children. Behav. Ther. 1990, 21, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, F.C.; Page, T.J.; Ivancic, M.T.; O’Brien, S. Effectiveness of brief time-out with and without contingent delay: A comparative analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1986, 19, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkovits, M.D.; O’Brien, K.A.; Carter, C.G.; Eyberg, S.M. Early identification and intervention for behavior problems in primary care: A comparison of two abbreviated versions of parent-child interaction therapy. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.W. Enforcing chair timeouts with room timeouts. Behav. Modif. 1988, 12, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, C.; Clemens-Mowrer, L.; Gurwitch, R.H.; Funderburk, B.W. Assessment of a new procedure to prevent timeout escape in preschoolers. Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 1994, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R.; Siegel, B.; Flaherty, E.G.; Gavril, A.R.; Idzerda, S.M.; Laskey, A.; Legano, L.A.; Leventhal, J.M.; Lukefahr, J.L.; Yogman, M.W.; et al. Effective discipline to raise healthy children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20183112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Everett, G.E.; Olmi, D.J.; Edwards, R.P.; Tingstrom, D.H.; Sterling-Turner, H.E.; Christ, T.J. An empirical investigation of time-out with and without escape extinction to treat escape-maintained noncompliance. Behav. Modif. 2007, 31, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Dadds, M. Practitioner review: When parent training doesn’t work: Theory-driven clinical strategies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaffin, M.; Silovsky, J.F.; Funderburk, B.; Valle, L.A.; Brestan, E.V.; Balachova, T.; Jackson, S.; Lensgraf, J.; Bonner, B.L. Parent-child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Driskell, J.E.; Willis, R.P.; Copper, C. Effect of overlearning on retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, J.R.; Niec, L.N. Coaching Parents to Change: The Impact of In Vivo Feedback on Parents’ Acquisition of Skills. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.; Funderburk, B.W. In vivo social regulation of high-risk parenting: A conceptual model of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for child maltreatment prevention. PsyArXiv 2021, PsyArXiv:agxd3. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/agxd3/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Barnett, M.L.; Niec, L.N.; Peer, S.O.; Jent, J.F.; Weinstein, A.; Gisbert, P.; Simpson, G. Successful Therapist–Parent Coaching: How In Vivo Feedback Relates to Parent Engagement in Parent–Child Interaction Therapy. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 46, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, E.I.; Wallace, N.M.; Kohlhoff, J.R.; Morgan, S.S.J.; McNeil, C.B. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with Toddlers: Improving Attachment and Emotion Regulation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, C.B.; Hembree-Kigin, T.L. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, S.C.; Timmer, S.G.; Blacker, D.M.; Urquiza, A.J. A positive behavioural intervention for toddlers: Parent-child attunement therapy. Child Abus. Rev. 2005, 14, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, C.B.; Quetsch, L.B.; Anderson, C.M. Handbook of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Clinical Practice; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski, M.; Maliken, A.C.; Lengua, L.J.; Gamache Martin, C.; Roos, L.E.; Everett, Y. Integrating dialectical behavior therapy with child and parent training interventions: A narrative and theoretical review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, e12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, M.E.; Havighurst, S.S.; Holland, K.A.; Frankling, E.J. The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havighurst, S.; Kehoe, C. The role of parental emotion regulation in parent emotion socialization: Implications for intervention. In Parental Stress and Early Child Development; Deater-Deckard, K., Panneton, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Troutman, B. Integrating Behaviorism and Attachment Theory in Parent Coaching; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. You Said WHAT About Time-Outs?! Available online: https://rb.gy/dg47mm (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Sailas, E.E.; Fenton, M. Seclusion and restraint for people with serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, A.T.; Taber-Thomas, S.M.; Schaffner, K.; Pemberton, J.R.; Hunter, L.; Herschell, A.D. A mixed-methods study of system-level sustainability of evidence-based practices in 12 large-scale implementation initiatives. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health, New Zealand Government. Interim Position Statement: Use of Time-Out in ICAMHS Settings. Available online: https://wharaurau.org.nz/resources/news/moh-interim-position-statement-use-time-out-icamhs-settings-20190315 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).