Entrepreneurship and Sport: A Strategy for Social Inclusion and Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

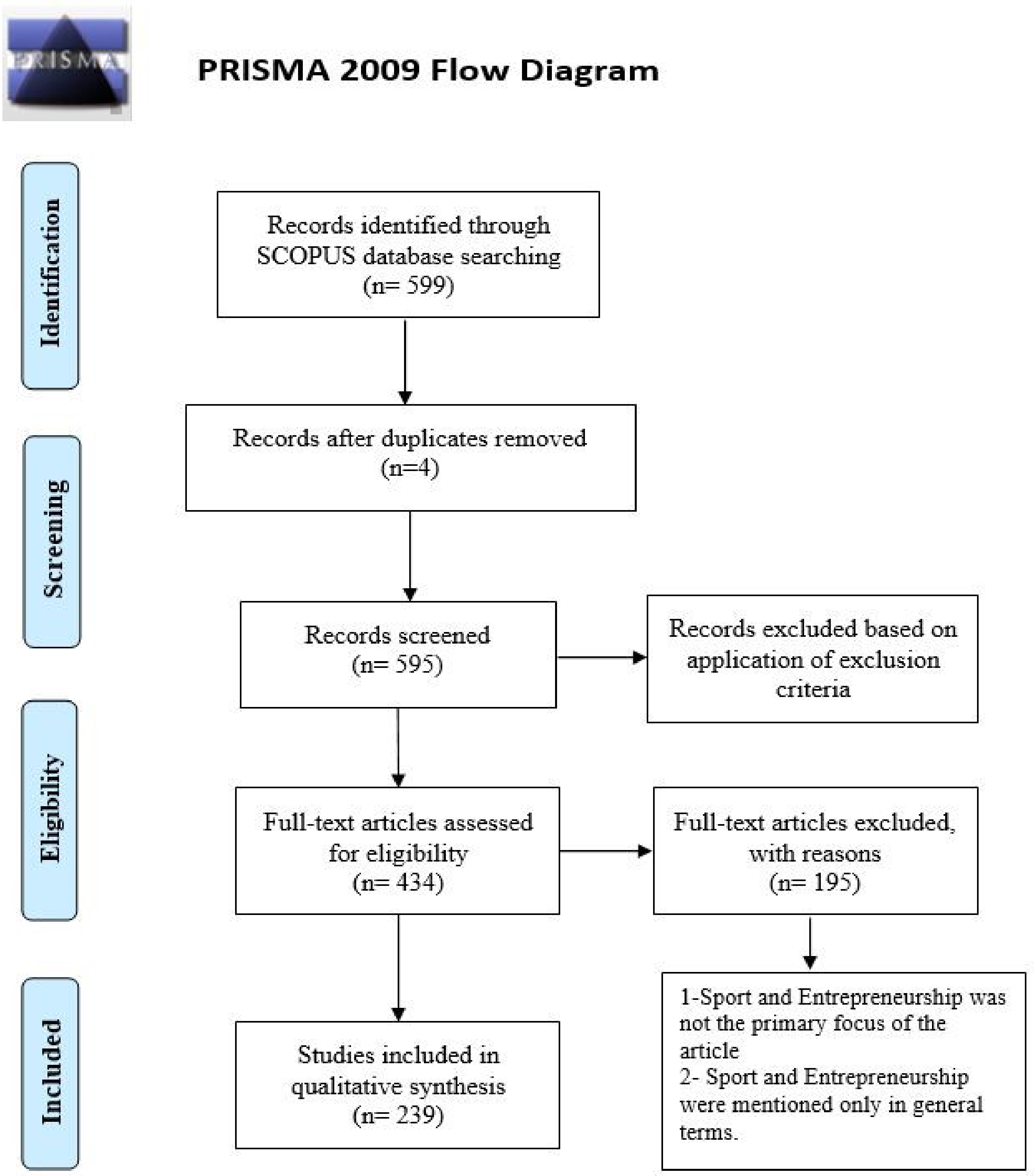

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

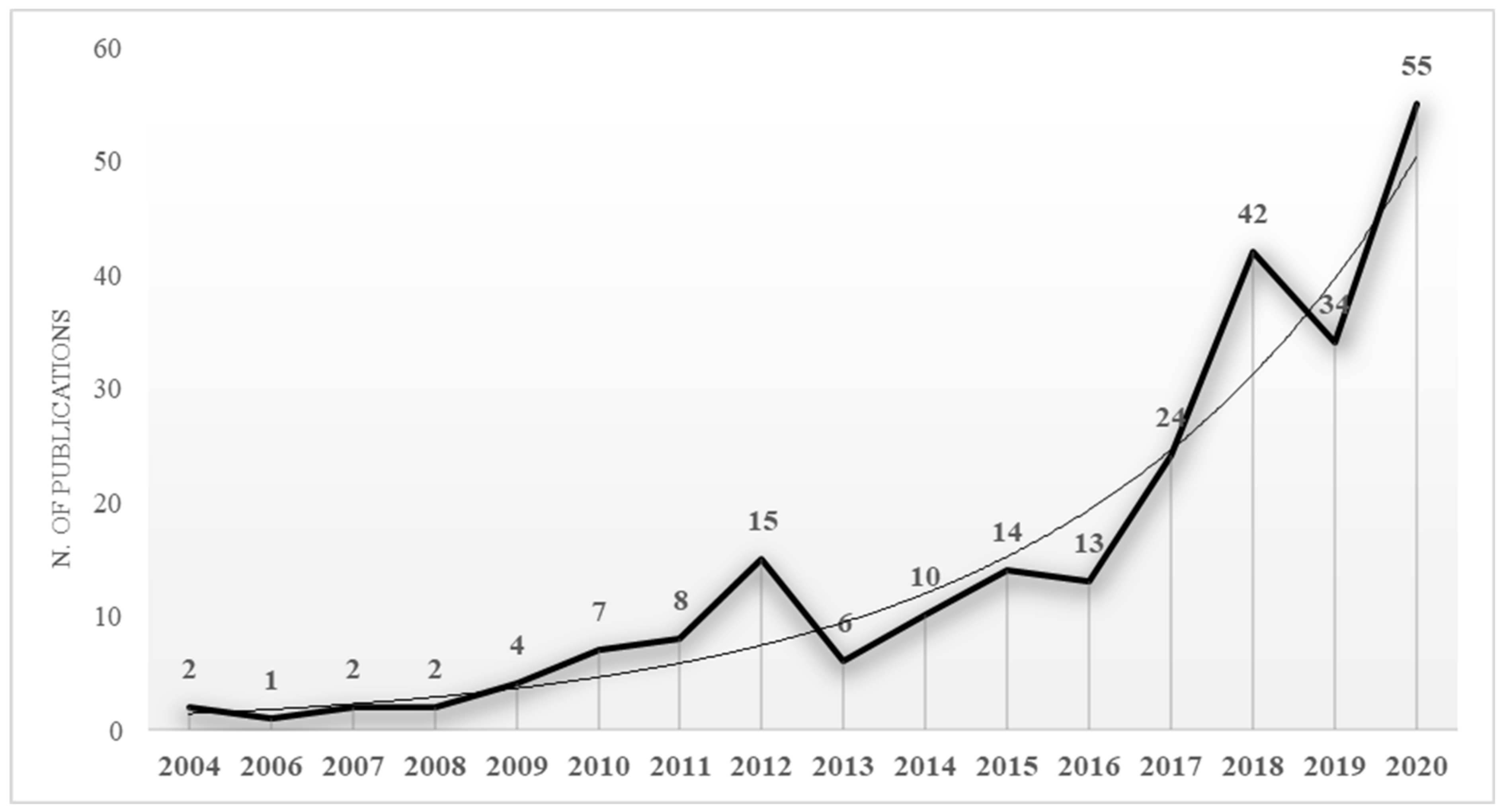

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

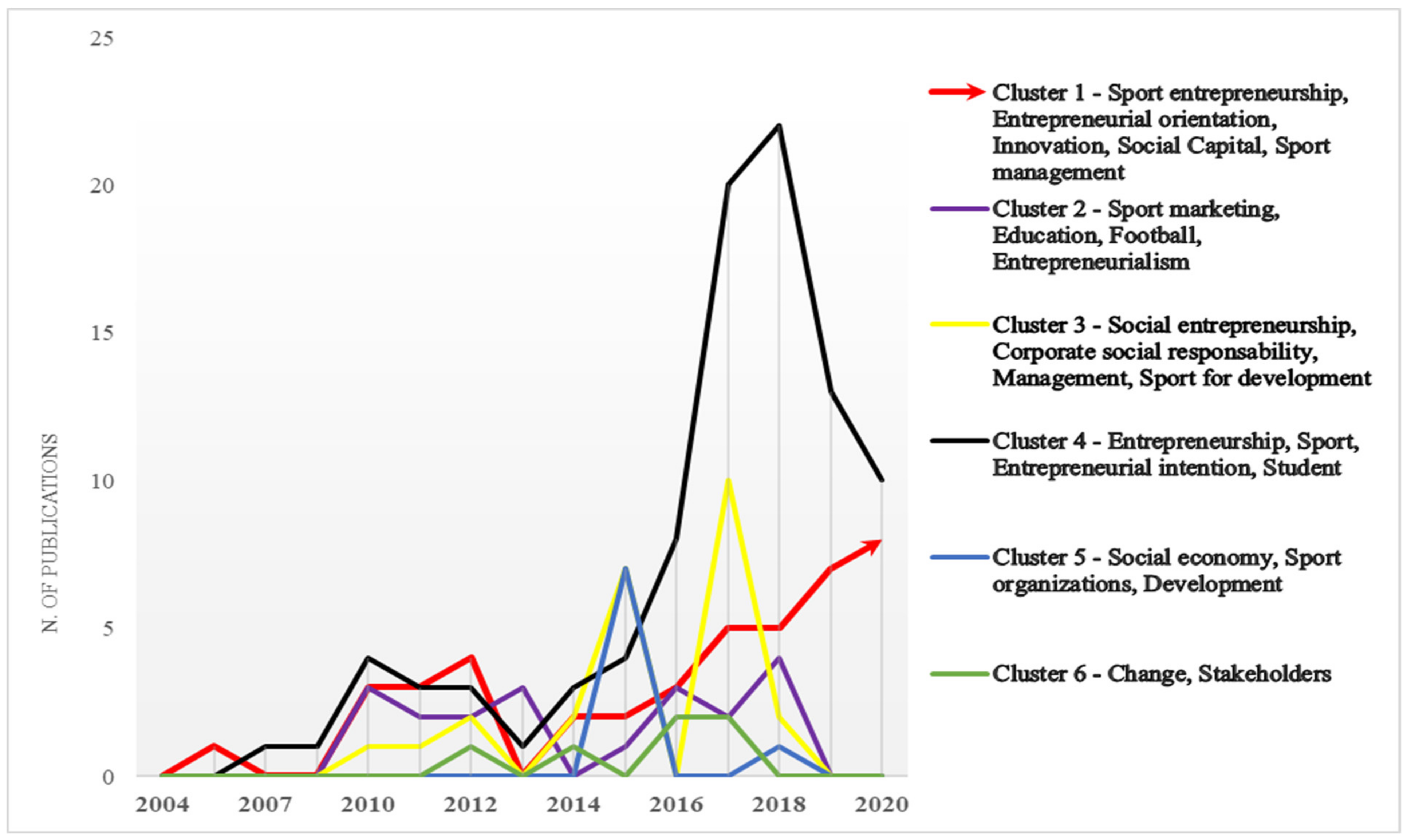

3.2. Topic Research on Sport Entrepreneurship

3.2.1. Cluster 1: Sport Entrepreneurship

3.2.2. Cluster 2: Sport Marketing and Education Role

3.2.3. Cluster 3: The Relationship between Sport and Social Entrepreneurship: A Tool for Solving Social Problems

3.2.4. Cluster 4: Entrepreneurial Intention and Sport

3.2.5. Cluster 5: The Effects of Sports Organizations on Social Economic Growth

3.2.6. Cluster 6: The Role of Stakeholders in the Development of Sports Enterprises

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gries, T.; Naudé, W.A. Entrepreneurship and Structural Economic Transformation. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 34, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefela, G.T. Entrepreneurship has emerged as the economics engine and social development throughout the world. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2012, 12, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fellnhofer, K.; Kraus, S. Examining attitudes towards entrepreneurship education: A comparative analysis among experts. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2015, 7, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Schneider, M. Phases of the adoption of innovation in organizations: Effects of environment, organization, and top managers. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Ventakaraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.T.; Stewart, B. The special features of sport: A critical revisit. Sport Manage. Rev. 2010, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyras, A.; Peachey, J.W. Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, S. Wellness in the Family Business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1993, 6, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. The importance of entrepreneurship to hospitality, leisure, sport and tourism. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Netw. 2005, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Eggers, F.; Kraus, S.; Jones, P.; Filser, M. Entrepreneurial orientation in sports entrepreneurship—A mixed methods analysis of professional soccer clubs in the German-speaking countries. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Sport-Based Entrepreneurship: Towards a New Theory of Entrepreneurship and Sport Management. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Toward a Theory of Community-Based Enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, D.; Gough, V. Calgary Flames: A case study in an entrepreneurial sport franchise. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2012, 4, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamplew, W. Products, Promotion and (Possibly) Profits: Sports Entrepreneurship Revisited. J. Sport Hist. 2018, 45, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S. Entrepreneurs, organizations, and the sport marketplace: Subjects in search of historians. J. Sport Hist. 1986, 13, 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Economic theory and entrepreneurial history. In Explorations in Enterprise; Aitken, H.G., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Sport entrepreneurship: Challenges and directions for future research. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2012, 4, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Levermore, R. English professional football clubs. SportsBus. Manag. 2012, 2, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D. New Combinations: Entrepreneurship in Sport History. Hitotsubashi Annu. Sports Stud. 2014, 33, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, P.N.; Stanescu, R.; Stanescu, M. Social Entrepreneurship and Sport in Romania: How Can Former Athletes Contribute to Sustainable Social Change? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Husin, S. Entrepreneurship Education in Sports: Issues and Challenges. Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Management, Finance & Entrepreneurship (ICMFE-2015), Medan, Indonesia, 11–12 April 2015; pp. 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nová, J. Developing the entrepreneurial competencies of sport management students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 3916–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Serrano, M.H.; Crespo Hervás, J.; Pérez-Campos, C. The importance of developing the entrepreneurial capacities in sport sciences university students. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 2017, 9, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naia, A.; Baptista, R.; Biscaia, R.; Januário, C.; Trigo, V. Entrepreneurial intentions of Sport Sciences Students And Theory of Planned Behavior. Mot. Rev. Educ. Fis. 2017, 23, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holienka, M.; Holienková, J.; Gál, P. Entrepreneurial Characteristics of Students in Different Fields of Study: A View from Entrepreneurship Education Perspective. Acta Univ. Agric. Et Silv. Mendel. Brun. 2018, 63, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Veken, K.; Lauwerier, E.; Willems, S. “To mean something to someone”: Sport-for-development as a lever for social inclusion. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haudenhuyse, R.P.; Theeboom, M.; Coalter, F. The potential of sports-based social interventions for vulnerable youth: Implications for sport coaches and youth workers. J. Youth Stud. 2012, 15, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C. Assessing the sociology of sport: On sport for development and peace. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2015, 50, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F. Sport and social inclusion: Evidence-based policy and practice. Social Inclusion 2017, 5, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N.; Sherry, E.; Rowe, K. Sport for development: An integrated literature review. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus database: A review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Coté, G.; Karimi, G. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sc. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Bachrach, D.G.; Podsakoff, N.P. The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ital. J. Public Health 2009, 7, 354–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clín. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: Vosviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring scholarly impact: Methods and practice; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Vallaster, C.; Kraus, S.; Nielsen, A.; Merigo Lindahl, J.M. Ethics and entrepreneurship: A bibliometric study and literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Merigó, J.M.; Valenzuela-Fernández, L.; Nicolás, C. Fifty years of the European journal of marketing: A bibliometric analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Entrepreneurship and Family Role: A Systematic Review of a Growing Research. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Women Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review to Outline the Boundaries of Scientific Literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altbach, P.G. Advancing the national and global knowledge economy: The role of research universities in developing countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreff, W. Sport in developing countries. In Handbook on the Economics of Sport; Andreff, W., Szymanski, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Auer, M.; Ritter, T. The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, W.; Elfring, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance: The moderating role of intra- and extra-industry social capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 51, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.C.; Barnett, T.; Dwyer, S.; Chadwick, K. Cultural Diversity in Management, Firm Performance, and the Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation Dimensions. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 32, 745–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anderson, B.S.; Kreiser, P.M.; Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J. Reconceptualizing Entrepreneurial Orientation. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Gupta, V.K.; Mousa, F.T. Empirical Research on Entrepreneurial Orientation: An Assessment and Suggestions for Future Research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 2011 31, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, A.; Skarmeas, D.; Lages, C. Entrepreneurial orientation, exploitative and explorative capabilities, and performance outcomes in export markets: A resource-based approach. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P.; Núñez Pomar, J.M.; Prado Gascó, V.J. Does the level of competition influence the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and service quality? J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeber, L.; Hoeber, O. Determinants of an innovation process: A case study of technological innovation in a community sport organization. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringuet-Riot, C.J.; Carter, S.; James, D.A. Programmed innovation in team sport using needs driven innovation. Procedia Eng. 2014, 72, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi Delarestaghi, A.; Razavi, S.M.H.; Boroumand, M.R. Identifying the Consequences of Strategic Entrepreneurship in Sports Business. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2017, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Ferreira, J. Entrepreneurship, innovation and sport policy: Implications for future research. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 2017, 9, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Serrano, M.H.; Añó Sanz, V.; González-García, R.J. Sustainable Sport Entrepreneurship and Innovation: A Bibliometric Analysis of This Emerging Field of Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of Past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Pomar, J.M.; Prado Gascó, V.J.; Añó Sanz, V.; Crespo Hervàs, J. Does size matter? Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in Spanish sports firms. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5336–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Jones, P. Future research directions for sport education: Toward an entrepreneurial learning approach. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, W.U. The implication of sports and sports marketing for entrepreneurship development in Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Res. Aca. Rev. 2015, 3, 204–210, ISSN: 2347-3215. [Google Scholar]

- Formica, P. Entrepreneurial universities: The value of education in encouraging entrepreneurship. Ind. High. Educ. 2002, 16, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.H.; Sauer, N.E.; Schmitt, P. Customer-based brand equity in the team sport industry. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, S.; Merz, G.R. The Four Domains of Sports Marketing: A Conceptual Framework. Sport Mark. Q. 2008, 17, 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V.; Ratten, H. International sport marketing: Practical and future research implications. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2011, 26, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundh, B.; Gottfridsson, P. Delivering Sports Events: The Arena Concept in Sports from Network Perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthinos, Y.; Nassis, P.; Theodorakis, N.D. An evaluation of the communication effectiveness of water polo: A content analytic study in Greece. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2010, 7, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D.; Gilmore, A.; Stolz, A. The strategic marketing of small sports clubs: From fundraising to social entrepreneurship. J. Strat. Mark. 2012, 20, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas Business Journal. Ranger Owner Talks Sports Business. Available online: http://www.dallas.bizjournals.com/dallas/stories/2007/05/07/daily47.html (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Chadwick, S. Promoting and celebrating sports marketing diversity. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D.; Carson, S. Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 1, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Keogh, W. Social enterprise: A case of terminological ambiguity and complexity. Soc. Enterp. J. 2006, 2, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.; Matear, M. Social Entrepreneurship: Why We Don’t Need a New Theory and How We Move Forward from Here. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.M.S. Investigating Social Entrepreneurship: A Multidimensional Model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerlin, J.A. Defining Social Enterprise Across Different Contexts: A Conceptual Framework Based on Institutional Factors. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2013, 42, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B. Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. In Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field; Mosher-Williams, R., Ed.; The Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei–Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Rev. Adm. 2012, 47, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Developing a theory of sport-based entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Ribeiro Soriano, D. Analyzing Social Entrepreneurship from an Institutional Perspective: Evidence from Spain. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility—Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.E.; Skillern, J.W.; Leonard, H.; Steverson, H. Entrepreneurship in the Social Sector; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía-Martínez, I.; Carrasco Monteagudo, I. The Role of CSR on Social Entrepreneurship: An International Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Peachey, J.W. The making of a social entrepreneur: From participant to cause champion within a sport-for-development context. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, N.; Grant, S. Social enterprise and corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, A.C.S. Social Entrepreneurship and Corporate Social Responsibility: Differences and Points in Common. J. Bus. Econ. Policy 2015, 2, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G. Corporate Social Responsibility through Sport. The Community Sports Trust Model as a CSR Delivery Agency. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2009, 35, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. The Future of Sports Management: A Social Responsibility, Philanthropy and Entrepreneurship Perspective. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian, E.; Nikkar, H.; Sadeghi, S. The Importance of Sports Entrepreneurship by Providing Appropriate Strategy Based on Views of Sport Managers. In Proceeding of the International Conference on Arts, Economics and Management (ICAEM’14), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 22–23 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, D.; Vamplew, W. Entrepreneurship, Sport, and History: An Overview. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2018, 35, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; English, J. A contemporary approach to entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. 2004, 46, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Serrano, M.H.; González-García, R.J.; Pérez-Campos, C. Entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions of sports science students: What are their determinant variables? J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.M.; Bedrule-Grigorută, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 1267, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Athletes as entrepreneurs: The role of social capital and leadership ability. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2015, 25, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, J.O.; Johnson, W.; Adeyemi, A. Entrepreneurship in sports and physical education in Nigerian universities: Challenges and prospects. In Proceeding of Lagos State University Faculty of Education International Conference, Lagos, Nigeria, 24–28 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Jones, A. Attitudes of Sports Development and Sports Management undergraduate students towards entrepreneurship. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinning, T. Preparing sports graduates for employment: Satisfying employers expectations. HESWBL 2017, 7, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Galera, G. The Concept and Practice of Social Enterprise. Lessons from the Italian Experience. Int. Rev. Soc. Res. 2012, 2, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Economic and Social Committee. Recent evolutions of the Social Economy in the European Union. Available online: http://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-04-17-875-en-n.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Tasaddoghi, Z.; Hossein Razavi, S.M.; Amirnezhad, S. Designing a success model for entrepreneurs in sports businesses. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2020, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, M.W.; Eys, M.A.; Wilson, K.S.; Côté, J. Group cohesion and positive youth development in team sport athletes. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2014, 3, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Colman, M.M.; Wheeler, J.; Stevens, D. Cohesion and Performance in Sport: A meta analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Soni, S.; Kishore, A. Exploring the Role of Social Media Communications in the Success of Professional Sports Leagues: An Emerging Market Perspective. J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 27, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.K. Change Management Drivers: Entrepreneurship and Knowledge Management. South Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2017, 6, vii–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, M.; D’Souza, C.; Polonsky, M. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility, reputation and business performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, P.G.; Hambrick, M.E. Exploring how external stakeholders shape social innovation in sport for development and peace. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas González-Serrano, M.; Jones, P.; Llanos-Contrera, O. An overview of sport entrepreneurship field: A bibliometric analysis of the articles published in the Web of Science. Sport Soc. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Rialti, R.; Marzi, G.; Caputo, A. Sport Entrepreneurship: A synthesis of existing literature and future perspectives. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 795–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, J.; Pike, E. Sports in society: Issues and Controversies; MacGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, L.M.; Merigó, J.M.; Johnston, W.J.; Nicolas, C.; Jaramillo, J.F. Thirty years of the journal of Business & Industrial Marketing: A bibliometric analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| R | N. Articles (Out 239) | Journals | Journal Metrics | Research Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h-Index | JIF | Scopus Citation | ||||

| 1 | 16 | Sport in Society | 34 | 0.93 | 368 | Sport Sc./Cultural Studies |

| 2 | 13 | Int J Hist Sport | 18 | 0.27 | 51 | Sport Sc./Social Sc. |

| 3 | 12 | Int Entrepreneurship Manag J | 50 | 3.47 | 207 | Business and Manag. |

| 4 | 10 | J Entrepreneurship Public Policy | 11 | 0.60 | 16 | Business and Manag./Social Sc. |

| 5 | 8 | Int J Sport Mang Mark | 21 | 0.55 | 63 | Business and Manag/Sport Sc. |

| 6 | 7 | Sport Management Review | 50 | 3.33 | 179 | Business and Manag/Sport Sc. |

| 7 | 6 | Int J Entrepreneurial Ventur | 14 | 0.43 | 88 | Business and Manag. |

| 7 | 6 | Int J Sport Policy | 22 | 1.98 | 86 | Social Science |

| 8 | 5 | Eur Sport Manag Q | 29 | 1.88 | 74 | Business and Manag/Sport Sc. |

| 8 | 5 | Journal of Sport Management | 61 | 2.35 | 126 | Business and Manag/Sport Sc. |

| 8 | 5 | Retos | 6 | 1.09 | 10 | Social Science |

| 8 | 5 | Sustainability | 68 | 2.59 | 18 | Environmental Sc./Social Sc. |

| R | N. Articles (Out 239) | Authors | Author Metrics | Affiliations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h-Index | Scopus Citations | Citation Per Documents | ||||

| 1 | 27 | Ratten, V. | 27 | 541 | 20.03 | La Trobe Business School, Australia |

| 2 | 7 | Escamilla-Fajardo, P. | 3 | 15 | 2.14 | University of Valencia, Spain |

| 3 | 6 | González-Serrano, M.H. | 4 | 32 | 5.33 | Universidad Católica de Valencia, Spain |

| 3 | 6 | Jones, P. | 21 | 96 | 16.0 | Prifysgol Abertawe, UK |

| 4 | 5 | Moreno, F.C. | 13 | 27 | 5.4 | University of Valencia, Spain |

| 4 | 5 | Núñez-Pomar, J.M. | 8 | 14 | 2.8 | University of Valencia, Spain |

| 4 | 5 | Valantine, I. | 6 | 26 | 5.2 | Lithuanian Sports University, Lithuania |

| Type of Research | % of the Sample | Type of Sample | % of the Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Research | 44.6% | Sports entrepreneurs/Managers | 23% |

| Athletes | 19.7% | ||

| Students/Youth | 9.2% | ||

| Quantitative Research | 32.6% | Sports Entrepreneurs/Managers | 21.9% |

| University Sports Students | 17.5% | ||

| Athletes | 4.6% | ||

| Mixed Approach | 2.4% | Sports Entrepreneurs | 2.3% |

| University Sports Students | 1.1% | ||

| Non-Empirical | 28.3% | ||

| Cluster | Keywords | % Articles | Example of Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sport Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurial Orientation, Innovation, Sport Entrepreneurship, Sport Management | 19.8% | Hammerschmidt et al. (2020). Entrepreneurial Orientation in Sports Entrepreneurship—A Mixed Methods Analysis of Professional Soccer Clubs in the German-Speaking Countries |

| 2. Sport Marketing and Educational Role | Education, Entrepreneurialism, Football, Sport Marketing | 11.3% | López-Carril, Villamón, McBride (2020). Social Media in Sport Management Education: Connecting Universities and Sport Industry |

| 3. The Relationship between Sport and Social Entrepreneurship: A Tool for Solving Social Problems | Corporate Social, Management, Social Entrepreneurship, Sport for Development | 14.1% | Miragaia, Ferreira, Ratten (2017). Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Entrepreneurship: Drivers of Sports Sponsorship Policy |

| 4. Entrepreneurial Intention and Sport | Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Intention, Sport, Students | 46.9% | Lara-Bocanegra et al. (2020). Effects of an Entrepreneurship Sport Workshop on Perceived Feasibility, Perceived Desirability, and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Pilot Study of Sports Science Students |

| 5. The Effects of Sports Organizations on Social and Economic Growth | Development, Social Economy, Sport Organization | 4.5% | Perez-Villalba, Fernandez-Gavira, Caballero-Blanco (2018). The Social Economy in the Sports Entrepreneurship of Spain |

| 6. The Role of Stakeholders in the Development of Sports Enterprises | Change, Stakeholders | 3.4% | Pittz T. et al. (2020). Sport Business Models: A Stakeholder Optimization Approach |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Entrepreneurship and Sport: A Strategy for Social Inclusion and Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094720

Cardella GM, Hernández-Sánchez BR, Sánchez-García JC. Entrepreneurship and Sport: A Strategy for Social Inclusion and Change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094720

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardella, Giuseppina Maria, Brizeida Raquel Hernández-Sánchez, and José Carlos Sánchez-García. 2021. "Entrepreneurship and Sport: A Strategy for Social Inclusion and Change" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094720

APA StyleCardella, G. M., Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., & Sánchez-García, J. C. (2021). Entrepreneurship and Sport: A Strategy for Social Inclusion and Change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094720