Assessing the Impact of a Hilly Environment on Depressive Symptoms among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

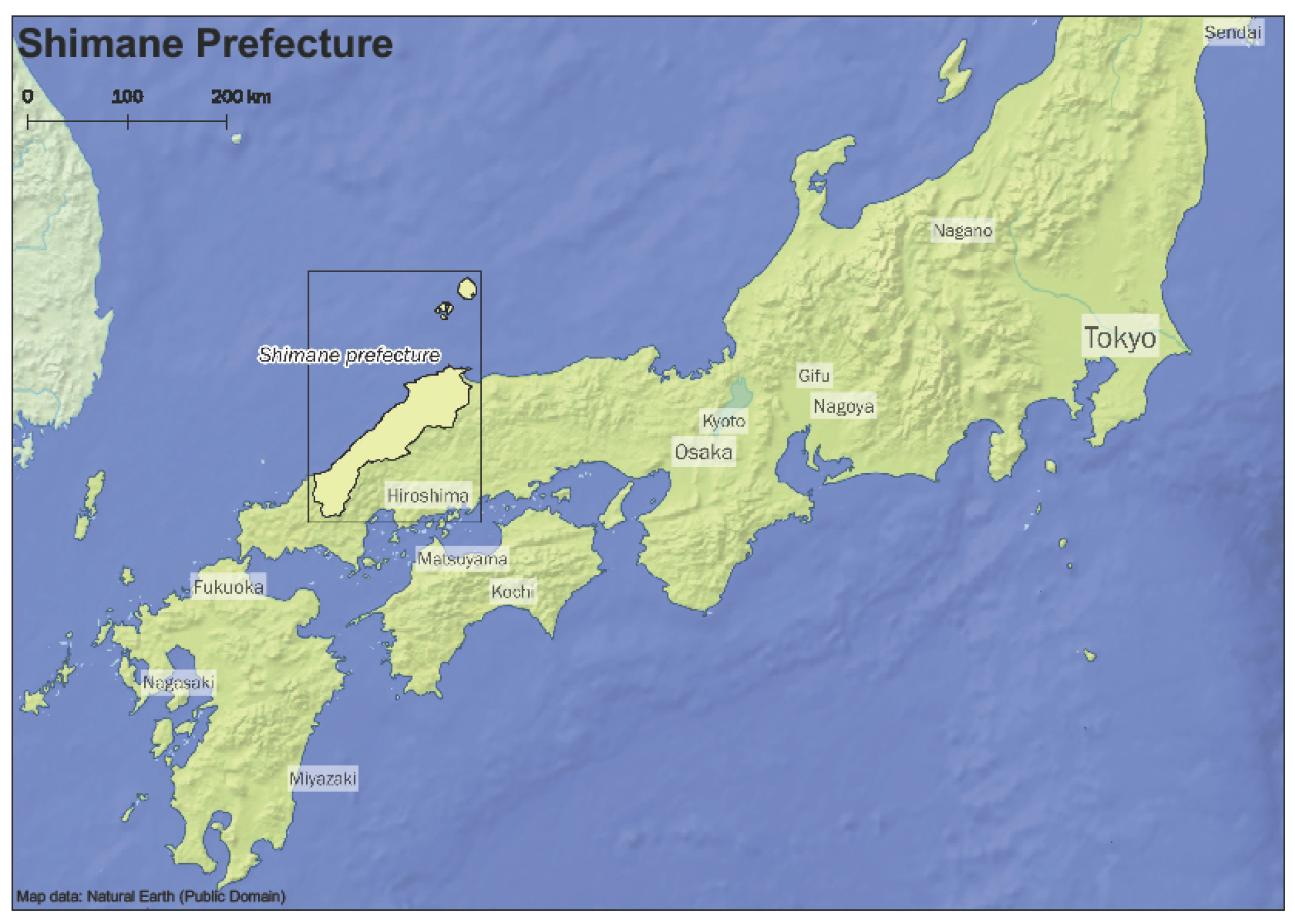

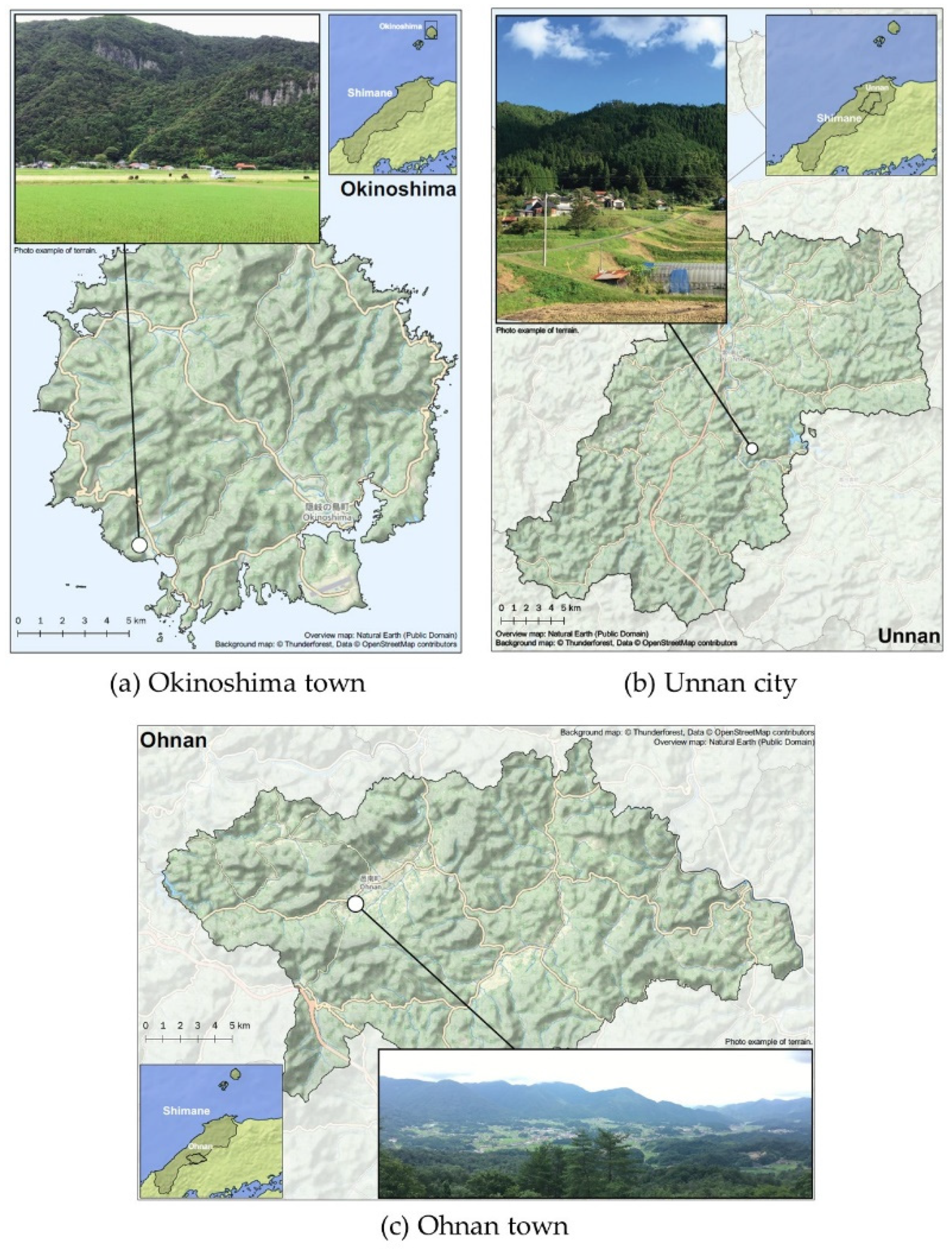

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Participants

2.4. Outcome Variable

2.5. Exposure Variable

2.6. Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodda, J.; Walker, Z.; Carter, J. Depression in older adults. BMJ 2011, 343, d5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depression. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/ (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool. 2020. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Cuijpers, P.; Vogelzangs, N.; Twisk, J.; Kleiboer, A.; Li, J.; Penninx, B.W. Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordentoft, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Pedersen, C.B. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Okereke, O.I.; Rexrode, K.M.; Hu, F.B. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA 2011, 306, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kooy, K.; van Hout, H.; Marwijk, H.; Marten, H.; Stehouwer, C.; Beekman, A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and meta analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.G.; Dendukuri, N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finan, P.H.; Smith, M.T. The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: Dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Mugisha, J.; Hallgren, M.; Probst, M.; Ward, P.B.; Gaughran, F.; De Hert, M.; et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, H. The associations between screen time-based sedentary behavior and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health 2019, 19, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, C.; Jongenelis, M.; Pettigrew, S. Modifiable protective and risk factors for depressive symptoms among older community-dwelling adults: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, A.; Zhang, C.J.P.; Johnston, J.M.; Cerin, E. Relationships between the neighborhood environment and depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Nakaya, T.; Oka, K. Activity-friendly built environments in a super-aged society, Japan: Current challenges and toward a research agenda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Historical Statistics of Japan, Chapter 1 Land and Climate, 1-6 Area by Configuration, Gradient and Prefecture Statistics Bureau of Japan. 2012. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/chouki/01.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Sakakibara, H.; Zhu, S.K.; Furuta, M.; Kondo, T.; Miyao, M.; Yamada, S.; Toyoshima, H. Knee pain and its associations with age, sex, obesity, occupation and living conditions in rural inhabitants of Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 1996, 1, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, S.R.; Wang, J. Chronic back pain and major depression in the general Canadian population. Pain 2004, 107, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Takamoto, I.; Amemiya, A.; Hanazato, M.; Suzuki, N.; Nagamine, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Tani, Y.; Yazawa, A.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Is a hilly neighborhood environment associated with diabetes mellitus among older people? Results from the JAGES 2010 study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 182, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Knuiman, M.; Koohsari, M.J.; Hickey, S.; Foster, S.; Badland, H.; Nathan, A.; Bull, F.; Giles-Corti, B. People living in hilly residential areas in metropolitan Perth have less diabetes: Spurious association or important environmental determinant? Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Tanaka, K.; Suyama, K.; Honda, S.; Senjyu, H.; Kozu, R. A comparison of objective physical activity, muscle strength, and depression among community-dwelling older women living in sloped versus non-sloped environments. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2016, 20, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Specific Health Checkups and Specific Health Guidance. 2013. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/seikatsu/index.html (accessed on 6 January 2021). (In Japanese)

- Zung, W.W.; Richards, C.B.; Short, M.J. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1965, 13, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, K.; Kobayashi, S. A study on a self-rating depression scale (author’s transl). Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1973, 75, 673–679. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Chida, F.; Okayama, A.; Nishi, N.; Sakai, A. Factor analysis of Zung Scale scores in a Japanese general population. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 58, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etman, A.; Kamphuis, C.B.; Pierik, F.H.; Burdorf, A.; Van Lenthe, F.J. Residential area characteristics and disabilities among Dutch community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2016, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Land Information Division, National Spatial Planning and Regional Policy Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan. Available online: https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/gml/datalist/KsjTmplt-G04-d.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Iizuka, Y.; Iizuka, H.; Mieda, T.; Tajika, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Ohsawa, T.; Sasaki, T.; Takagishi, K. Association between neck and shoulder pain, back pain, low back pain and body composition parameters among the Japanese general population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015, 16, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Abe, T.; Hamano, T.; Takeda, M.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Nabika, T. Hilly neighborhoods are associated with increased risk of weight gain among older adults in rural Japan: A 3-years follow-up study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2019, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, N.; Katsumura, T.; Ueda, C.; Inoue, S.; Shimomitsu, T. Validity and reliability of Japanese version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire. J. Health Welfare. Stat 2002, 49, 1–9. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Mammen, G.; Faulkner, G. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: A systematic review of prospective studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Mure, K.; Takeshita, T.; Arita, M. Relationships between lifestyle, living environments, and incidence of hypertension in Japan (in men): Based on participant’s data from the nationwide medical check-up. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Kubota, T.; Tsubaki, H.; Yamauchi, K. Analysis of impact of geographic characteristics on suicide rate and visualization of result with geographic information system. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamano, T.; Kamada, M.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Shiwaku, K. Association of overweight and elevation with chronic knee and low back pain: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 4417–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, G.; Moreschi, C.; Rigatti-Luchini, S.; Merskey, H. Prospective study on the relationship between depressive symptoms and chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 1994, 56, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinen, K.E.; Rantakokko, M.; Suomi, K.; Rantanen, T.; Portegijs, E. Hilliness and the development of walking difficulties among community-dwelling older people. J. Aging. Health 2020, 32, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaoyang, R.; Martire, L.M.; Darnall, B.D. Daily pain catastrophizing predicts less physical activity and more sedentary behavior in older adults with osteoarthritis. Pain 2020, 161, 2603–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Ohya, Y.; Odagiri, Y.; Takamiya, T.; Kamada, M.; Okada, S.; Oka, K.; Kitabatake, Y.; Nakaya, T.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. Perceived neighborhood environment and walking for specific purposes among elderly Japanese. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Sia, A.; Fogel, A.; Ho, R. Can exposure to certain urban green spaces trigger frontal alpha asymmetry in the brain? Preliminary findings from a Passive Task EEG Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Throner, V.; Kirschneck, M.; Immich, G.; Frisch, D.; Schuh, A. The psychological and physical effects of forests on human health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Battagliese, G.; Feige, B.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Nissen, C.; Voderholzer, U.; Lombardo, C.; Riemann, D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; Jang, S.; Kim, H.; Chang, B.S.; Lee, C.K.; Yeom, J.S. Depression is closely associated with chronic low back pain in patients over 50 years of age: A cross-sectional study using the sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-2). Spine 2018, 43, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraki, S.; Akune, T.; Oka, H.; Mabuchi, A.; En-Yo, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Saika, A.; Nakamura, K.; Kawaguchi, H.; Yoshimura, N. Association of occupational activity with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and lumbar spondylosis in elderly patients of population-based cohorts: A large-scale population-based study. Arthritis. Rheum. 2009, 61, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total | No Depressive Symptoms | Depressive Symptoms 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 935 | 720 (77.0) | 215 (23.0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 360 (38.5) | 276 (76.7) | 84 (23.3) | 0.85 |

| Female | 575 (61.5) | 444 (77.2) | 131 (22.8) | |

| Age | ||||

| 65–74 years old | 718 (76.8) | 552 (76.9) | 166 (23.1) | 0.87 |

| ≥75 years old | 217 (23.2) | 168 (77.4) | 49 (22.6) | |

| Body mass index (Asian cut-off) | ||||

| Underweight, <18.5 kg/m2 | 69 (7.4) | 51 (73.9) | 18 (26.1) | 0.44 |

| Normal weight, 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 | 502 (53.7) | 381 (75.9) | 121 (24.1) | |

| Overweight, ≥23.0 kg/m2 | 364 (38.9) | 288 (79.1) | 76 (20.9) | |

| Current smoking | ||||

| No | 874 (93.5) | 675 (77.2) | 199 (22.8) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 61 (6.5) | 45 (73.8) | 16 (26.2) | |

| Current alcohol drinking | ||||

| No | 505 (54.0) | 389 (77.0) | 116 (23.0) | 0.99 |

| Yes | 430 (46.0) | 331 (77.0) | 99 (23.0) | |

| Physical activity | ||||

| ≥150 min/week | 795 (85.0) | 615 (77.4) | 180 (22.6) | 0.54 |

| <150 min/week | 140 (15.0) | 105 (75.0) | 35 (25.0) | |

| Sedentary time | ||||

| <3 h/day | 388 (41.5) | 297 (76.5) | 91 (23.5) | 0.78 |

| ≥3 h/day | 547 (58.5) | 423 (77.3) | 124 (22.7) | |

| Getting enough sleep | ||||

| Yes | 749 (80.1) | 620 (82.8) | 129 (17.2) | <0.01 |

| No | 186 (19.9) | 100 (53.8) | 86 (46.2) | |

| Lower back pain | ||||

| No | 488 (52.2) | 401 (82.2) | 87 (17.8) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 447 (47.8) | 319 (71.4) | 128 (28.6) | |

| Educational years | ||||

| ≥12 years | 375 (40.1) | 284 (75.7) | 91 (24.3) | 0.45 |

| <12 years | 560 (59.9) | 436 (77.9) | 124 (22.1) | |

| Residential area | ||||

| Okinoshima town | 114 (12.2) | 92 (80.7) | 22 (19.3) | 0.06 |

| Unnan city | 365 (39.0) | 292 (80.0) | 73 (20.0) | |

| Ohnan town | 456 (48.8) | 336 (73.7) | 120 (26.3) | |

| Land slope, degree, median (IQR) | 9.19 (5.89, 12.65) | 8.84 (5.71, 12.47) | 10.49 (6.50, 16.94) | 0.01 |

| Crude Model | Adjusted Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Land slope | 1.04 | (1.01, 1.08) | 0.01 | 1.04 | (1.01, 1.08) | 0.02 | |

| Sex | Male | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.88 | (0.60, 1.31) | 0.54 | ||||

| Age | 65–74 years old | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| ≥75 years old | 1.55 | (0.95, 2.52) | 0.08 | ||||

| Body mass index (Asian cut-off) | Underweight, <18.5 kg/m2 | 1.19 | (0.65, 2.20) | 0.58 | |||

| Normal weight, 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 | 1 | (reference) | |||||

| Overweight, ≥23.0 kg/m2 | 0.81 | (0.57, 1.15) | 0.24 | ||||

| Current smoking | No | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 1.21 | (0.64, 2.31) | 0.56 | ||||

| Current alcohol drinking | No | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 0.91 | (0.62, 1.33) | 0.63 | ||||

| Physical activity | ≥150 min/week | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| <150 min/week | 1.01 | (0.64, 1.59) | 0.96 | ||||

| Sedentary time | <3 h/day | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| ≥3 h/day | 0.95 | (0.68, 1.32) | 0.74 | ||||

| Getting enough sleep | Yes | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| No | 4.24 | (2.94, 6.13) | <0.01 | ||||

| Lower back pain | No | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 1.66 | (1.19, 2.30) | <0.01 | ||||

| Educational years | ≥12 years | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| <12 years | 0.82 | (0.59, 1.14) | 0.24 | ||||

| Residential area | Okinoshima | 1 | (reference) | ||||

| Unnan | 0.75 | (0.42, 1.35) | 0.34 | ||||

| Ohnan | 1.44 | (0.78, 2.66) | 0.25 | ||||

| Cox and Snell R Square | 0.007 | 0.094 | |||||

| Nagelkerke R Square | 0.011 | 0.142 | |||||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test, p-value | 0.790 | 0.293 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abe, T.; Okuyama, K.; Hamano, T.; Takeda, M.; Yamasaki, M.; Isomura, M.; Nakano, K.; Sundquist, K.; Nabika, T. Assessing the Impact of a Hilly Environment on Depressive Symptoms among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094520

Abe T, Okuyama K, Hamano T, Takeda M, Yamasaki M, Isomura M, Nakano K, Sundquist K, Nabika T. Assessing the Impact of a Hilly Environment on Depressive Symptoms among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094520

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbe, Takafumi, Kenta Okuyama, Tsuyoshi Hamano, Miwako Takeda, Masayuki Yamasaki, Minoru Isomura, Kunihiko Nakano, Kristina Sundquist, and Toru Nabika. 2021. "Assessing the Impact of a Hilly Environment on Depressive Symptoms among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094520

APA StyleAbe, T., Okuyama, K., Hamano, T., Takeda, M., Yamasaki, M., Isomura, M., Nakano, K., Sundquist, K., & Nabika, T. (2021). Assessing the Impact of a Hilly Environment on Depressive Symptoms among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094520