Model of Organizational Commitment Applied to Health Management Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Organizational Commitment in Healthcare Institutions

1.2. Rationale and Structure of the Research

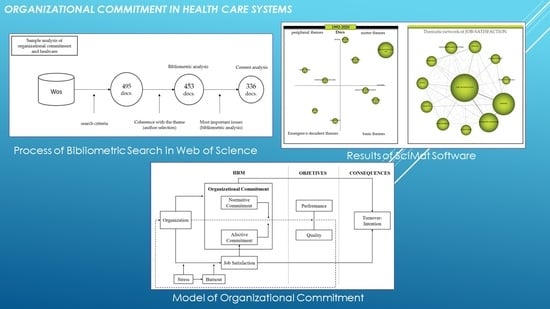

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

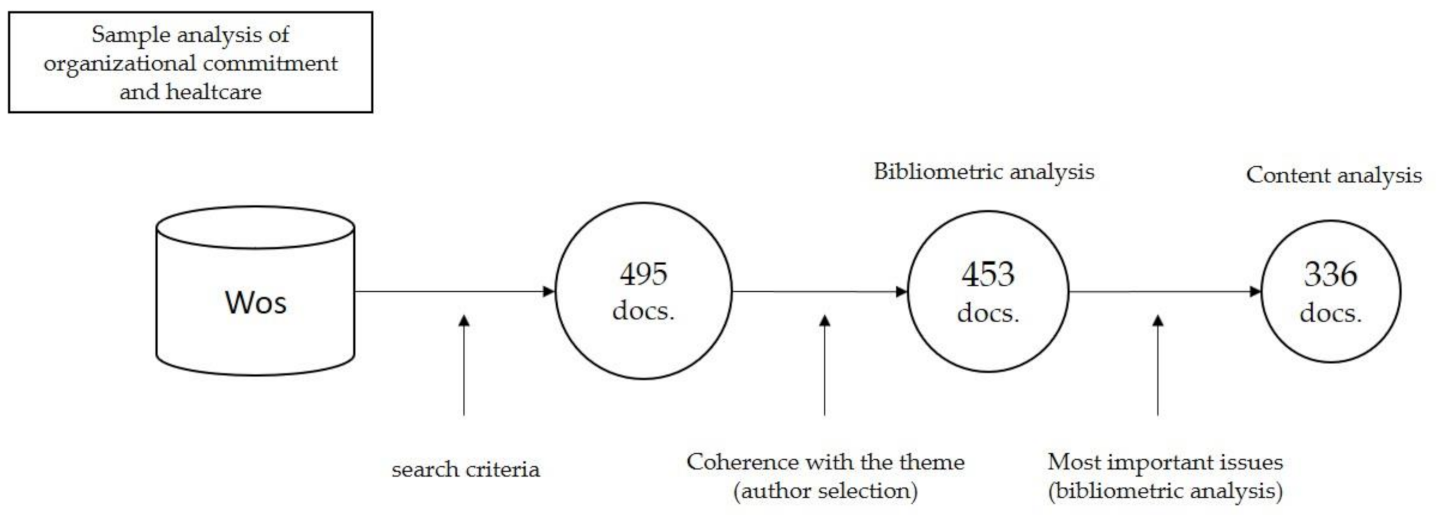

2.2. Software

3. Results

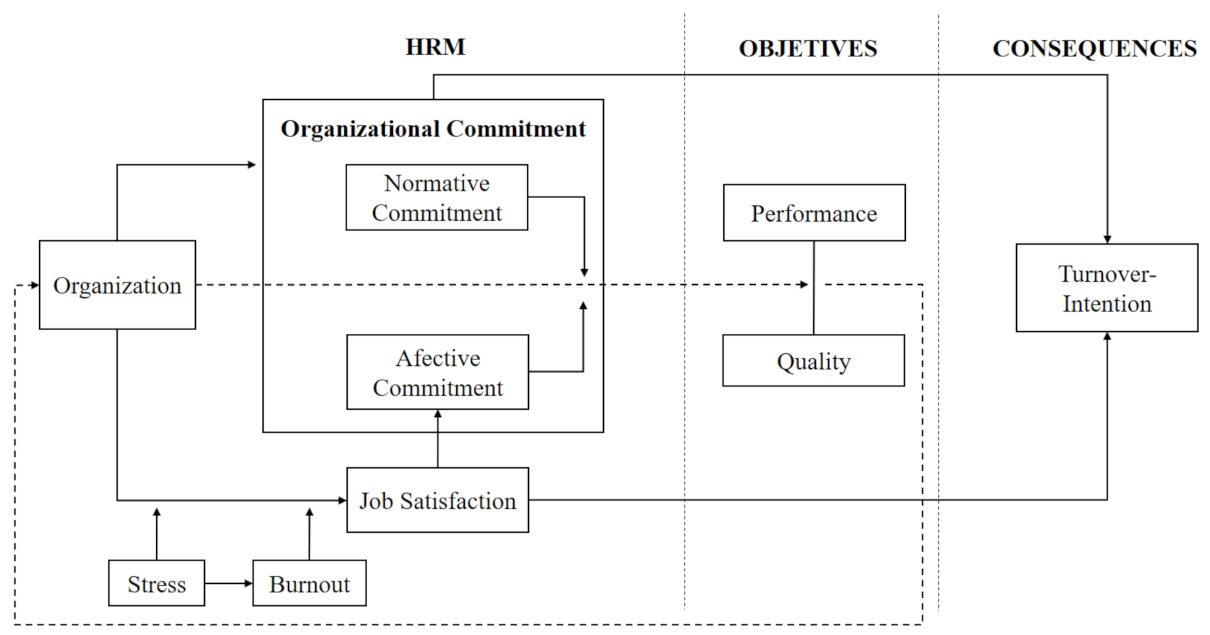

3.1. Proposed Model of Organizational Commitment in Health Organizations

3.2. Interpretation of the Proposed Model

3.2.1. Organizational Commitment

Factors that Enhance Organizational Commitment

Factors Undermining the Development of Organizational Commitment

Affective Commitment

Normative Commitment

3.2.2. Job Satisfaction

Factors Negatively Influencing Job Satisfaction. Effects of Stress

Factors Negatively Influencing Job Satisfaction. Effects of Burnout Syndrome

3.2.3. Turnover Intention

Factors Favoring the Intention to Quit in the Health Sector

Factors Favoring the Intention to Remain in the Workplace

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006—Working Together for Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/index.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Bartram, T.; Casimir, G.; Djurkovic, N.; Leggat, S.G.; Stanton, P. Do perceived high performance work systems influence the relationship between emotional labour, burnout and intention to leave? A study of Australian nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipton, H.; Sanders, K.; Atkinson, C.; Frenkel, S. Sense-giving in health care: The relationship between the HR roles of line managers and employee commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 26, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.; Birnbaum, D.; Casal, J. Application of the person-centered model to stress and well-being research: An inves-tigation of profiles of employee well-being. Empl. Relat. 2019, 41, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, F.; Locander, W.B. Emotional exhaustion and organizational deviance: Can the right job and a leader’s style make a difference? J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L.; Berta, W.; Cleverley, K.; Medeiros, C.; Widger, K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, C. Antecedents and consequences of nurses’ burnout: Leadership effectiveness and emotional intelligence as moderators. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, A.; Veneziani, C.A.; Metta, M. Affective organizational commitment and dispositional mindfulness as correlates of burnout in health care professionals. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2016, 31, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Liou, S.-R. Intention to leave of Asian nurses in US hospitals: Does cultural orientation matter?: Cultural orienta-tion and intention to leave. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2033–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinkman, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Salanterä, S. Nurses’ intention to leave the profession: Integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadatsafavi, H.; Walewski, J.; Shepley, M.M. The influence of facility design and human resource management on health care professionals. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S. The influence of frontline manager job strain on burnout, commitment and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, L.W.; Lawer, E.E. Managerial Attitudes and Performance; Irwin: Homewood, AL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.; Baron, R.A. Behavior in Organizations: Understanding and Managing the Human Side of Work; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: An Examination of Construct Validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 49, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somunoğlu İkinci, S.İ.N.E.M.; Erdem, E.; Erdem, U. Organizational Commitment in Healthcare Sector Workers: Sample of Denizli City 2012. Available online: https://avesis.uludag.edu.tr/yayin/37d22da7-2b52-4d0c-8d4d-27d8cb38506e/organizational-commitment-in-healthcare-sector-workers-sample-of-denizli-city (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Top, M.; Tarcan, M.; Tekingündüz, S.; Hikmet, N. An analysis of relationships among transformational leadership, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and organizational trust in two Turkish hospitals. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2012, 28, e217–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, M.; Puhakka, V. Inspiring organizational commitment: Responsible leadership and organizational inclusion in the Egyptian health care sector. J. Manag. Dev. 2019, 38, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, K.M. Motivation for entry, occupational commitment and intent to remain: A survey regarding Registered Nurse retention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2532–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoo, V.; Abdullah, K.L.; Piaw, C.Y. The relationship between job satisfaction and intention to leave current employment among registered nurses in a teaching hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3141–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinno, S.; Partanen, P.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Hospital nurses’ work environment, quality of care provided and career plans. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011, 58, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtom, B.C.; O’Neill, B.S. Job Embeddedness: A theoretical foundation for developing a comprehensive nurse retention plan. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2004, 34, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeau, K.V.; Williams, E.S.; Wagar, T.H. Developing human capital: What is the impact on nurse turnover? J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgulu, O.; Akilli, A. The determination of the levels of burnout syndrome, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction of the health workers. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 20, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heras-Rosas, C.D.L.; Herrera, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M. Organisational Commitment in Healthcare Systems: A Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. A bibliometric analysis of international impact of business incubators. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEYCT. Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología. Available online: https://www.recursoscientificos.fecyt.es/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Cobo, M. SciMAT: Software Tool for the Analysis of the Evolution of Scientific Knowledge. Proposal for an Evaluation Methodology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Han, K.; Ryu, E.; Choi, E. Work Schedule Characteristics, Missed Nursing Care, and Organizational Commitment Among Hospital Nurses in Korea. J. Nurs. Sch. 2021, 53, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y. The mediating role of organizational commitment between calling and work engagement of nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Weyman, A.K.; Plugor, R.; Nolan, P. Institutional commitment and aging among allied health care professionals in the British National Health Service. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2020, 0951484820918513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Alonso, M.; Topa, G. Prevention of Occupational Strain: Can Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Commitment Decrease Dissatisfaction and Intention to Quit? J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.L.; Van De Ven, A.H. The Changing Nature of Change Resistance: An Examination of the Moderating Impact of Time. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 52, 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negussie, N.; Berehe, C. Factors affecting performance of public hospital nurses in Addis Ababa region, Ethiopia. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2016, 91, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haroon, H.I.; Al-Qahtani, M.F. Assessment of Organizational Commitment Among Nurses in a Major Public Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Health 2020, 13, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwane, V. Role of Biographical Characteristics and Employee Engagement on State Hospital Employees’ Commitment. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance 2018, Bankok, Thailand, 24–25 May 2018; pp. 120–129. Available online: http://dev.siu.edu.in/sites/default/files/q346/images/SIBMP_3.4.6_17.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Liu, J.; Mao, Y. Continuing medical education and work commitment among rural healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study in 11 western provinces in China. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorska-Simmons, E. Predictors of Organizational Commitment among Staff in Assisted Living. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, G.L.; Olsan, T.; Drew-Cates, J.; DeVinney, B.C.; Davies, J. Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Career Intent. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2002, 32, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, M.A.S.; Youseff, M.R.L.; El Fatah, S.A.A.; Ibrahem, S.K.; Gomaa, N.A. The relationship between health care providers’ perceived work climate, organizational commitment, and caring efficacy at pediatric intensive care units, Cairo University. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell-Ellis, R.S.; Jones, L.; Longstreth, M.; Neal, J. Spirit at work in faculty and staff organizational commitment. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2015, 12, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.I.J.; Gregory, D.M. Spirit at Work (SAW): Fostering a Healthy RN Workplace. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 37, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeese-Smith, D.K. A Nursing Shortage: Building Organizational Commitment Among Nurses. J. Health Manag. 2001, 46, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top, M.; Akdere, M.; Tarcan, M. Examining transformational leadership, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and organizational trust in Turkish hospitals: Public servants versus private sector employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 26, 1259–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, V.M.; Višnjić, A.; Jović, S.; Radulović, O.; Šargić, Č.; Mihajlović, J.; Mladenović, J. Organizational commitment and job satisfaction among nurses in Serbia: A factor analysis. Nurs. Outlook 2014, 62, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Way, C.; Gregory, D.; Davis, J.; Baker, N.; LeFort, S.; Barrett, B.; Parfrey, P. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Clinical Managers’ Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intentions. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2007, 37, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdere, M.; Gider, O.; Top, M. Examining the role of employee focus in the Turkish healthcare industry. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 23, 1241–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, M.; Heydari, N.; Torabizadeh, C. Nurses’ perspectives regarding the relationship between professional ethics and organizational commitment in healthcare organizations. J. Med. Ethic. Hist. Med. 2020, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskenvuori, J.; Numminen, O.; Suhonen, R. Ethical climate in nursing environment: A scoping review. Nurs. Ethic. 2017, 26, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Song, M. Exploring how and when ethical conflict impairs employee organizational commitment: A stress perspective investigation. Bus. Ethic. A Eur. Rev. 2021, 30, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, A.; Aslan, M. The Relationship Between the Quality of Work and Organizational Commitment of Prison Nurses. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 27, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrani, A.; Hoxha, A.; Gabrani (CYCO), J.; Petrela (ZAIMI), E.; Zaimi, E.; Avdullari, E. Perceived organizational commitment and job satisfaction among nurses in Albanian public hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Manag. 2016, 9, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.A.L.; Chong, J. Contributions of job content and social information on organizational commitment and job satisfaction: An exploration in a Malaysian nursing context. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, C.; Ishqaidef, G.; May, D.R. Improving work environments in health care: Test of a theoretical framework. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, C.; Sahin, B.; Teke, K.; Ucar, M.; Kursun, O. Organizational Commitment of Military Physicians. Mil. Med. 2009, 174, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, N.; Rai, H. The correlation effects between recruitment, selection, training, development and employee stress, satisfaction and commitment: Findings from a survey of 30 hospitals in India. Int. J. Health Technol. Manag. 2015, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, J.; Uzoka, F.-M.; Aladi, F.; El-Hussein, M.; El-Hussein, M. Understanding the Factors That Determine Registered Nurses’ Turnover Intentions. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2014, 28, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, D.; Butler, L.; Fitch, M.; Green, E.; Olson, K.; Cummings, G. Canadian cancer nurses’ views on recruitment and retention. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoglu, A. Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitment and perceived organizational performance: Empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashish, E.A.A. Relationship between ethical work climate and nurses’ perception of organizational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Nurs. Ethic. 2017, 24, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosak, J.; Dawson, J.; Flood, P.; Peccei, R. Employee involvement climate and climate strength. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2017, 4, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. Work Engagement of Nurses in Private Hospitals: A Study of Its Antecedents and Mediators. J. Health Manag. 2016, 18, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, S.A.; Rohrer, W.W.; Al-Surimi, K.; Da’Ar, O.O.; Ahmed, A. The association of leadership styles and empowerment with nurses’ organizational commitment in an acute health care setting: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, F.; Siahkali, S.R.; Shoghli, A.; Pazargadi, M.; Tafreshi, M.Z. Investigation of the relationship between structural empowerment and organizational commitment of nurses in Zanjan hospitals. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 17, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghbeen, M.; Rahmanian, E. The relationship between empowerment and organizational commitment of nursing staff in hospitals affiliated to jahrom university of medical sciences in 2015. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2017, 9, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, A.; Griffin, M.T.Q.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Structural empowerment and anticipated turnover among critical care nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 19, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C.; McMahon, L.; Kaufmann, C. Leader Behavior Impact on Staff Nurse Empowerment, Job Tension, and Work Effectiveness. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 1999, 29, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, C.M.S.; Gouveia, A.L.; Pinto, C.A.B.; Mónico, L.D.S.M.; Correia, M.M.F.; Parreira, P.M.S.D. Empowerment em profissionais de saúde: Uma revisão da literatura. Psychologica 2017, 60, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Köse, S.D.; Köse, T.; Uğurluoğlu, Ö. The Antecedent of Organizational Outcomes Is Psychological Capital. Health Soc. Work 2018, 43, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Oranye, N.O. Empowerment, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A comparative analysis of nurses working in Malaysia and England. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Han, K.; Ryu, E. Authentic leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of nurse tenure. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Fry, L.W. The role of spiritual leadership in reducing healthcare worker burnout. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2018, 15, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, L.; Gibson, P. How to increase organizational commitment through transactional leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, D.; Remdisch, S. Gesundhealith-soriented Leadierste Fühiprung in the Gderiatric Care Sector. The Role of Social Job Demands and Resources for Employees’ HeAlth and Commitmentpflege. Z. Arb. Organ. A O 2016, 60, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Ergün, E. Managers’ Task-Oriented and Employee-Oriented Leadership Behaviors: Effects on Nurse Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Stress. Florence Nightingale Hemşirelik Derg. 2015, 23, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Konja, V.; Grubić-Nešić, L.; Lalić, D. Leader-Member Exchange Influence on Organizational Commitment among Serbian Hospital Workers. HealthMED 2012. Available online: https://open.uns.ac.rs/handle/123456789/9371 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kónya, V.; Grubić-Nešić, L.; Matić, D. The Influence of Leader-Member Communication on Organizational Commitment in a Central European Hospital. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2015, 12, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusio, H.; Heponiemi, T.; Sinervo, T.; Elovainio, M. Organizational commitment among general practitioners: A cross-sectional study of the role of psychosocial factors. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2010, 28, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Weng, R.-H. Exploring the antecedents and consequences of mentoring relationship effectiveness in the healthcare environment. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveinsdóttir, H.; Ragnarsdóttir, E.D.; Blöndal, K. Praise matters: The influence of nurse unit managers’ praise on nurses’ practice, work environment and job satisfaction: A questionnaire study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 72, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.S.; Chang, H.C. Perceptions of internal marketing and organizational commitment by nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepahvand, F.; Mohammadipour, F.; Parvizy, S.; Tafreshi, M.Z.; Skerrett, V.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F. Improving nurses’ organizational commitment by participating in their performance appraisal process. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intepeler, S.S.; Esrefgil, G.; Yilmazmis, F.; Bengu, N.; Dinc, N.G.; Ileri, S.; Ataman, Z.; Dirik, H.F. Role of job satisfaction and work environment on the organizational commitment of nurses: A cross-sectional study. Contemp. Nurse 2019, 55, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.; Lee, D.R.; Prout, K. Organizational commitment among physicians: A systematic literature review. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, E.; Priporas, C.-V. The effect of internal marketing on job satisfaction in health services: A pilot study in public hospitals in Northern Greece. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ma, T.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Deng, J. Perceived social support and presenteeism among healthcare workers in China: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovner, C.T.; Brewer, C.S.; Greene, W.; Fairchild, S. Understanding new registered nurses’ intent to stay at their jobs. Nurs. Econ. 2009, 27, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, J.; Demir, D.; Parris, M.; Steane, P.; Noblet, A. The impact of bullying on health care administration staff: Reduced commitment beyond the influences of negative affectivity. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, R.L.; Mohammed, S.; Hopkins, M.; Shapiro, D.; Dellasega, C. The Negative Impact of Organizational Cynicism on Physicians and Nurses. Health Care Manag. 2014, 33, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, B.C. Abusive Supervision and Nursing Performance. Nurs. Forum 2013, 48, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, A.; Farokhzadian, J.; Foroughameri, G. Nurses’ professional competency and organizational commitment: Is it important for human resource management? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máynez-Guaderrama, A.I. Cultura y compromiso afectivo: ¿influyen sobre la transferencia interna del conocimiento? Contaduría Adm. 2016, 61, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Regge, M.; Van Baelen, F.; Aerens, S.; Deweer, T.; Trybou, J. The boundary-spanning behavior of nurses: The role of support and affective organizational commitment. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, V.; Aubé, C. Social Support at Work and Affective Commitment to the Organization: The Moderating Effect of Job Resource Adequacy and Ambient Conditions. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelsen, H.; Conway, P.M.; Clausen, T. Is organizational justice climate at the workplace associated with individual-level quality of care and organizational affective commitment? A multi-level, cross-sectional study on dentistry in Sweden. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 91, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Casier, S. Organizational Trust and Empowerment in Restructured Healthcare Settings. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2000, 30, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Hoeven, C.L.; Verhoeven, J.W. “Sharing is caring”: Corporate social responsibility awareness explaining the relationship of information flow with affective commitment. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2013, 18, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.M.F.D.C.; Azevedo, R.M.M. Empowering and trustful leadership: Impact on nurses’ commitment. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, S.Y.; Forret, M.L.; Wolff, H.-G. Internal and external networking behavior: An Investigation of Relationships with Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woznyj, H.M.; Heggestad, E.D.; Kennerly, S.; Yap, T.L. Climate and organizational performance in long-term care facilities: The role of affective commitment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, J.T.; Sambrook, S. Psychological contracts and commitment amongst nurses and nurse managers: A discourse analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussami, M.; Darawad, M.; Saleh, A.; Hayajneh, F.A. Predicting nurses’ turnover intentions by demographic characteristics, perception of health, quality of work attitudes. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 20, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yürümezoğlu, H.A.; Kocaman, G.; Haydari, S.M. Predicting nurses’ organizational and professional turnover intentions. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 16, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellatly, I.R.; Cowden, T.L.; Cummings, G.G. Staff Nurse Commitment, Work Relationships, and Turnover Intentions: A Latent Profile Analysis. Nurs. Res. 2014, 63, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, V.; Yildirim, A. Healthcare professionals’ exposure to mobbing behaviors and relation of mobbing with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 120, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M.; Ashktorab, T.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F. Ethical leadership outcomes in nursing: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethic. 2017, 25, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sencan, N.; Yeğenoğlu, S.; Aydintan, B. Researches conducted on job satisfaction and organizational commitment of health professionals and pharmacists. Marmara Pharm. J. 2013, 2, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.A. Job satisfaction of nurses in a regional hospital in Oman: A cross-sectional survey. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 23, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alboliteeh, M. Factors influencing job satisfaction amongst nurses in Hail Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; While, A.E.; Barriball, K.L. Job satisfaction and its related factors: A questionnaire survey of hospital nurses in Mainland China. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, I.T.; Samdal, G.B.; Hansen, B.S.; Tørstad, S.; Hamilton, G.A. Job satisfaction in a Norwegian population of nurses: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Asenjo, M.; Sánchez, M. Job satisfaction among emergency department staff. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2017, 20, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atefi, N.; Abdullah, K.L.; Wong, L.P. Job satisfaction of Malaysian registered nurses: A qualitative study: Job satisfaction of nurses. Nurs. Crit. Care 2014, 21, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Barriball, K.L.; Zhang, X.; While, A.E. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses revisited: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Norman, I.J. An investigation of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and role conflict and ambiguity in a sample of Chinese undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2006, 26, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.-Y.; Chang, L.-C.; Wu, H.-L. Relationships Between Professional Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Work Stress in Public Health Nurses in Taiwan. J. Prof. Nurs. 2007, 23, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, G.; Russell, K.C. Examining the Role of Expectations and Perceived Job Demand Stressors for Field Instructors in Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 2013, 30, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadiga, M.; Nemera, G.; Hailu, E.; Mosisa, G. Relationship between nurses’ perception of ethical climates and job satisfaction in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Oromia region, south west Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatam, N.; Fardid, M.; Kavosi, Z. A path analysis of the effects of nurses’ perceived organizational justice, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction on their turnover intention. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2018, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsounis, A.; Niakas, D.; Sarafis, P. Social capital and job satisfaction among substance abuse treatment employees. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2017, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Ramachandran, A. A path analysis study of retention of healthcare professionals in urban India using health information technology. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dahinten, V.; Lee, S.; Macphee, M. Disentangling the relationships between staff nurses’ workplace empowerment and job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Purdy, N.; Almost, J. The Impact of Leader-Member Exchange Quality, Empowerment, and Core Self-evaluation on Nurse Manager’s Job Satisfaction. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2007, 37, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caricati, L.; La Sala, R.; Marletta, G.; Pelosi, G.; Ampollini, M.; Fabbri, A.; Ricchi, A.; Scardino, M.; Artioli, G.; Mancini, T. Work climate, work values and professional commitment as predictors of job satisfaction in nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 22, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, D.A. Generational Differences of the Frontline Nursing Workforce in Relation to Job Satisfaction: What does the literature reveal? Health Care Manag. 2013, 32, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, I.; Akyürek, C.E.; Yavuz, Ş. Assessment of Effect of Leadership Behaviour Perceptions and Organizational Commitment of Hospital Employees on Job Satisfaction with Structural Equation Modelling. J. Health Manag. 2014, 16, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proenca, E.J. Team dynamics and team empowerment in health care organizations. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddourah, B.; Abu-Shaheen, A.K.; Al-Tannir, M. Quality of nursing work life and turnover intention among nurses of tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velando-Soriano, A.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ramírez-Baena, L.; De La Fuente, E.I.; La Fuente, G.A.C. Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: A systematic review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 17, e12269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, M.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.; Linares, J.G.; Márquez, M.S.; Martínez, Á.M. Burnout Risk and Protection Factors in Certified Nursing Aides. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılıç, E.; Altuntaş, S. The effect of collegial solidarity among nurses on the organizational climate. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, J.I.; Prikshat, V.; Shum, P.; Suganthi, L. Follower emotional intelligence: A mediator between transformational lead-ership and follower outcomes. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinval, J.; Marques-Pinto, A.; Queirós, C.; Marôco, J. Work Engagement among Rescue Workers: Psychometric Properties of the Portuguese UWES. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, D.; Bagotyriute, R.; Urbach, T.; West, M.A.; Dawson, J. Differential effects of workplace stressors on innovation: An integrated perspective of cybernetics and coping. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Korczynski, M. When Caring and Surveillance Technology Meet: Organizational Commitment and Discretion-ary Effort in Home Care. Work Occup. 2010, 37, 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCunn, L.J.; Wright, J. Hospital employees’ perceptions of circadian lighting: A pharmacy department case study. J. Facil. Manag. 2019, 17, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, O.; Ozturk, C.; Bektas, M.; Ayar, D.; Armstrong, M. Job satisfaction and burnout among paediatric nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, Z.L.; Holcombe, K.J.; McCluney, C.L.; Fisher, G.G.; McGonagle, A.K.; Friebe, S.J. Burnout and Engagement: Relative Im-portance of Predictors and Outcomes in Two Health Care Worker Samples. Workplace Health Saf. 2016, 64, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittschof, K.R.; Fortunato, V.J. The Influence of Transformational Leadership and Job Burnout on Child Protective Services Case Managers’ Commitment and Intent to Quit. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, K.; Khan, A.; Alam, M.T. Causes and Adverse Impact of Physician Burnout: A Systematic Review. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2017, 27, 495–501. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Assoc-Prof-Dr-Kamran-Azam/publication/321039405_Causes_and_Adverse_Impact_of_Physician_Burnout_A_Systematic_Review/links/5a80a3bfaca272a73769e627/Causes-and-Adverse-Impact-of-Physician-Burnout-A-Systematic-Review.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Marques, M.M.; Alves, E.; Queirós, C.; Norton, P.; Henriques, A. The effect of profession on burnout in hospital staff. Occup. Med. 2018, 68, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.Y. Supervisory Communication, Burnout, and Turnover Intention Among Social Workers in Health Care Settings. Soc. Work Health Care 2009, 48, 364–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permarupan, P.Y.; Al Mamun, A.; Samy, N.K.; Saufi, R.A.; Hayat, N. Predicting Nurses Burnout through Quality of Work Life and Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards Sustainable Healthcare Services in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Saki, M.; Pour, A.H.H. Nurses’ perception of empowerment and its relationship with organizational commitment and trust in teaching hospitals in Iran. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Fraser, K.; Wong, C.A.; Muise, M.; Cummings, G. Factors influencing intentions to stay and retention of nurse managers: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 21, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, N.J.; MacLeod, M.L.P.; Kosteniuk, J.G.; Olynick, J.; Penz, K.L.; Karunanayake, C.P.; Kulig, J.C.; Labrecque, M.E.; Morgan, D.G. The importance of organizational commitment in rural nurses’ intent to leave. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 3398–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, M.R.; Tourangeau, A.E. Staying in nursing: What factors determine whether nurses intend to remain employed? J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowden, T.L.; Cummings, G.G. Testing a theoretical model of clinical nurses’ intent to stay. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaither, C.A.; Kahaleh, A.A.; Doucette, W.R.; Mott, D.A.; Pederson, C.A.; Schommer, J.C. A modified model of pharmacists’ job stress: The role of organizational, extra-role, and individual factors on work-related outcomes. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2008, 4, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Hung, C. Predictors of nurses’ intent to continue working at their current hospital. Nurs. Econ. 2017, 35, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, D.; Snyder, L.A.; Litwiller, B.J. Promoting retention of nurses: A meta-analytic examination of causes of nurse turnover. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homsuwan, W. Factors associated with intention to leave of nurses in Rajavithi hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2017, 31 (Suppl. 1), s91–s97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschell, A.D.; Kolko, D.J.; Hart, J.A.; Brabson, L.A.; Gavin, J.G. Mixed method study of workforce turnover and evidence-based treatment implementation in community behavioral health care settings. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 102, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, S.; De Vries, D.H.; Tijdens, K.G. Should I stay or should I go? The impact of working time and wages on retention in the health workforce. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M. Effects of recognition of flexible work systems, organizational commitment, and quality of life on turnover intentions of healthcare nurses. Technol. Health Care 2019, 27, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Demers, M.; Austin, S. Motivational pathways of occupational and organizational turnover intention among newly registered nurses in Canada. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontrager, S.M.; Hart, P.L.; Mareno, N. The Role of Preceptorship and Group Cohesion on Newly Licensed Registered Nurses’ Satisfaction and Intent to Stay. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2016, 47, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, P.P.L.; Wu, C.H.; Kwong, C.K.; Ching, W.K. Nursing shortage in the public healthcare system: An exploratory study of Hong Kong. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J. Related Factors of Turnover Intention Among Pediatric Nurses in Mainland China: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 53, e217–e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshareef, A.G.; Wraith, D.; Dingle, K.; Mays, J. Identifying the factors influencing Saudi Arabian nurses’ turnover. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneroth, M.; Sendén, M.G.; Gustafsson, K.S.; Wall, M.; Fridner, A. Threats or violence from patients was associated with turnover intention among foreign-born GPs—A comparison of four workplace factors associated with attitudes of wanting to quit one’s job as a GP. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2017, 35, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Battistelli, A.; Portoghese, I.; Galletta, M.; Pohl, S. Beyond the tradition: Test of an integrative conceptual model on nurse turnover. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2013, 60, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Poutasi, C. Attitudinal variables predicting intent to quit among Pacific healthcare workers. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 49, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampinen, M.-S.; Suutala, E.; Konu, A.I. Sense of community, organizational commitment and quality of services. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2017, 30, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nangoli, S.; Kemboi, A.; Lagat, C.; Namono, R.; Nakyeyune, S.; Muhumuza, B. Strategising for continuance commitment: The role of servant leadership behaviour. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Mayende, S.T. Ethical leadership and staff retention in Uganda’s health care sector: The mediating effect of job resources. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerdegen, A.C.S.; Aikins, M.; Amon, S.; Agyemang, S.A.; Wyss, K. Managerial capacity among district health managers and its association with district performance: A comparative descriptive study of six districts in the Eastern Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanste, O.; Lipponen, K.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kyngäs, H. Effects of network development on attitudes towards work and well-being at work among health care staff in northern Finland. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2010, 69, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M.J.; Reid, S.R.M. Human resources and innovative behaviour: Improving nursing performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 1850019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Sadeghmoghadam, L.; Hosseinzadeh, F.; Bahri, N. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence with Job and Individual Characteristics of Nursing Staff. J. Health Saf. Work 2020, 10, 290–300. Available online: http://jhsw.tums.ac.ir/article-1-6375-en.html (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Bikmoradi, A.; Abdi, F.; Soltanian, A.; Dmoqadam, N.F.; Hamidi, Y. Nurse Managers’ Emotional Intelligence in Educational Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study from the West of Iran. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, IC07–IC11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, K.J.; Carmody, M.; Silk, K.J. The influence of organizational culture, climate and commitment on speaking up about medical errors. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourakos, M.; Kafkia, T. Organizational Culture: Its Importance for Healthcare Service Providers and Recipients. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 2019. Available online: http://mail.mednet.gr/archives/2019-3/312abs.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Boselie, P. High performance work practices in the health care sector: A Dutch case study. Int. J. Manpow. 2010, 31, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-I.; Chang, H. Explaining turnover intention in Korean public community hospitals: Occupational differences. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2008, 23, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, H. Anticipated nurses’ turnover in public hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 25, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeeque, S.H.; Bilal, A.; Babar, S.; Khan, Z.; Rahman, S.U. How Patient-Perpetrated Workplace Violence Leads to Turnover Intention Among Nurses: The Mediating Mechanism of Occupational Stress and Burnout. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2017, 27, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, M.J.; Fitzgerald, G.; Clark, M. The relationship between quality of work life and turnover intention of primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, C.S.; Kovner, C.T.; Greene, W.; Tukov-Shuser, M.; Djukic, M. Predictors of actual turnover in a national sample of newly licensed registered nurses employed in hospitals. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 68, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Smith, M.; Pilgrim, N.; Wynia, M.; Desai, M.M.; Bright, C.; Krumholz, H.M.; Bradley, E.H. Health Care Workplace Discrimination and Physician Turnover. J. Natl. Med Assoc. 2009, 101, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudine, A.; Thorne, L. Nurses’ ethical conflict with hospitals: A longitudinal study of outcomes. Nurs. Ethic. 2012, 19, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ali, G.; Ahmed, I. Protecting healthcare through organizational support to reduce turnover intention. Int. J. Hum. Rights Health 2018, 11, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Rutte, C.G. Absenteeism, turnover intention and inequity in the employment relationship. Work. Stress 1999, 13, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Chien, C.; Lin, C.; Hsiao, C.Y. Understanding hospital employee job stress and turnover intentions in a practical setting. J. Manag. Dev. 2005, 24, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, B. Linking Organizational Commitment and Organizational Trust in Health Care Organizations. Organizacija 2020, 53, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, K.; Hussain, K.; Afzal, M.; Gilani, S.A. Determining the association of high-commitment human resource practices with nurses’ compassionate care behaviour: A cross-sectional investigation. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 28, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goštautaitė, B.; Bučiūnienė, I.; Milašauskienė, Ž. HRM and work outcomes: The role of basic need satisfaction and age. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, N.; Sugalski, J.; Krause, D.; Butterfield, R.; Zhang, N.; Smedley, W.; Stewart, F.M.; Griffin, J.M.; Zafar, Y.; Lee, S. Current practice for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN member institutions. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plourde, N.; Brown, H.K.; Vigod, S.; Cobigo, V. Contextual Factors Associated with Uptake of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Women Health 2016, 56, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.E.; Sylling, P.W.; Mor, M.K.; Fine, M.J.; Nelson, K.M.; Wong, E.S.; Liu, C.-F.; Batten, A.J.; Fihn, S.D.; Hebert, P.L. Developing an Algorithm for Combining Race and Ethnicity Data Sources in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil. Med. 2019, 185, e495–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Akkadechanunt, T.; Nantsupawat, A.; Stark, A.T. A contemporary understanding of nurses’ workplace social capital: A response to the rapid changes in the nursing workforce. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 28, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.E.; Hewko, S.J.; Pfaff, K.A.; Cleghorn, L.; Cunningham, B.J.; Elston, D.; Cummings, G.G. Leaders’ experiences and perceptions implementing activity-based funding and pay-for-performance hospital funding models: A systematic review. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowen, C.R.; McFadden, K.L.; Hoobler, J.M.; Tallon, W.J. Exploring the efficacy of healthcare quality practices, employee commitment, and employee control. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 24, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R.; Stolt, M.; Katajisto, J.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Review of sampling, sample and data collection procedures in nursing research—An example of research on ethical climate as perceived by nurses. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 29, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Godkin, L.; Fleischman, G.M.; Kidwell, R. Corporate Ethical Values, Group Creativity, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention: The Impact of Work Context on Work Response. J. Bus. Ethic. 2010, 98, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, C.; Ind, N.; Angelis, J.; Sherry-Watt, P. Challenge of Change in the Public Sector: Living the Brand, Innovation Diffusion and the NHS. In Proceedings of the 6th International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics, Tampere, Finland, 15–17 June 2011; Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A480696&dswid=910 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Taghavi, S.; Riahi, L.; Nasiripour, A.A.; Jahangiri, K. Modeling Customer Relationship Management Pattern Using Human Factors Approach in the Hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Health Scope 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Node A | Node B | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Job-Satisfaction | Turnover-Intention | 0.36 |

| 2 | Job-Satisfaction | Nurses | 0.35 |

| 3 | Nurses | Turnover-Intention | 0.25 |

| 4 | Job-Satisfaction | Stress | 0.15 |

| 5 | Burnout | Stress | 0.15 |

| 6 | Job-Satisfaction | Work | 0.12 |

| 7 | Job-Satisfaction | Performance | 0.11 |

| 8 | Nurses | Quality | 0.10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Fernández, M.; Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Model of Organizational Commitment Applied to Health Management Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094496

Rodríguez-Fernández M, Herrera J, de las Heras-Rosas C. Model of Organizational Commitment Applied to Health Management Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094496

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Fernández, Mercedes, Juan Herrera, and Carlos de las Heras-Rosas. 2021. "Model of Organizational Commitment Applied to Health Management Systems" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094496

APA StyleRodríguez-Fernández, M., Herrera, J., & de las Heras-Rosas, C. (2021). Model of Organizational Commitment Applied to Health Management Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094496