The Role of Healthcare Professionals’ Passion in Predicting Secondary Traumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Growth in the Face of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Variables and Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

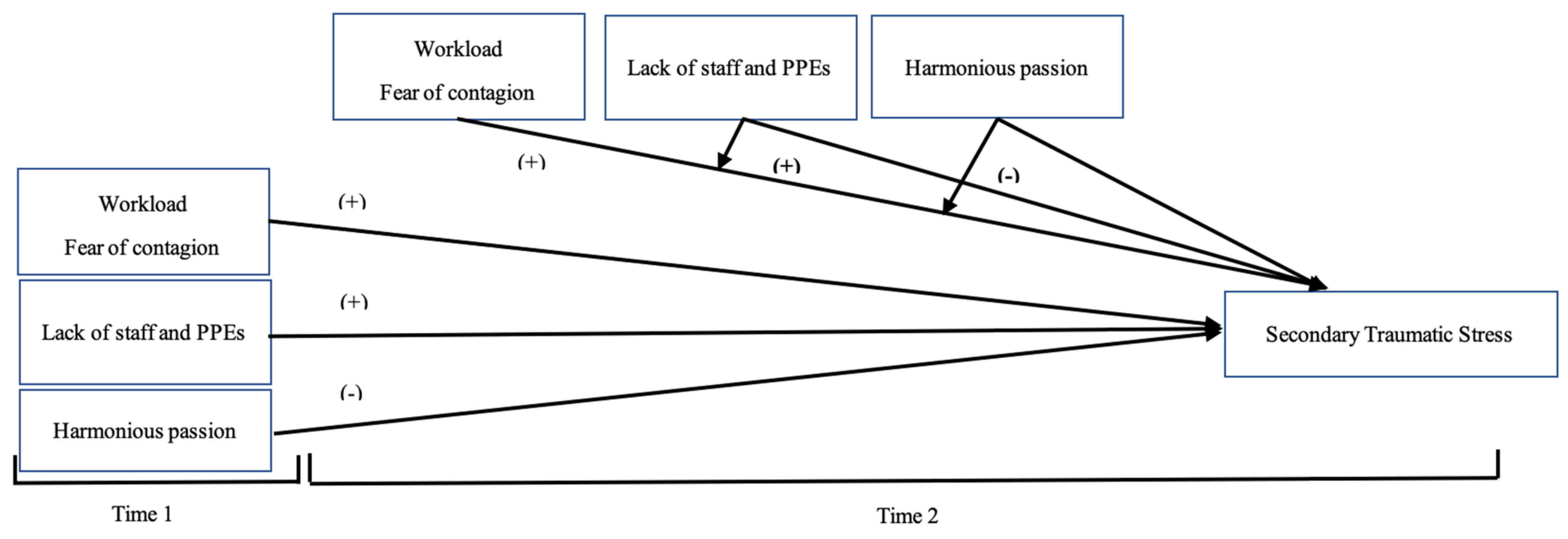

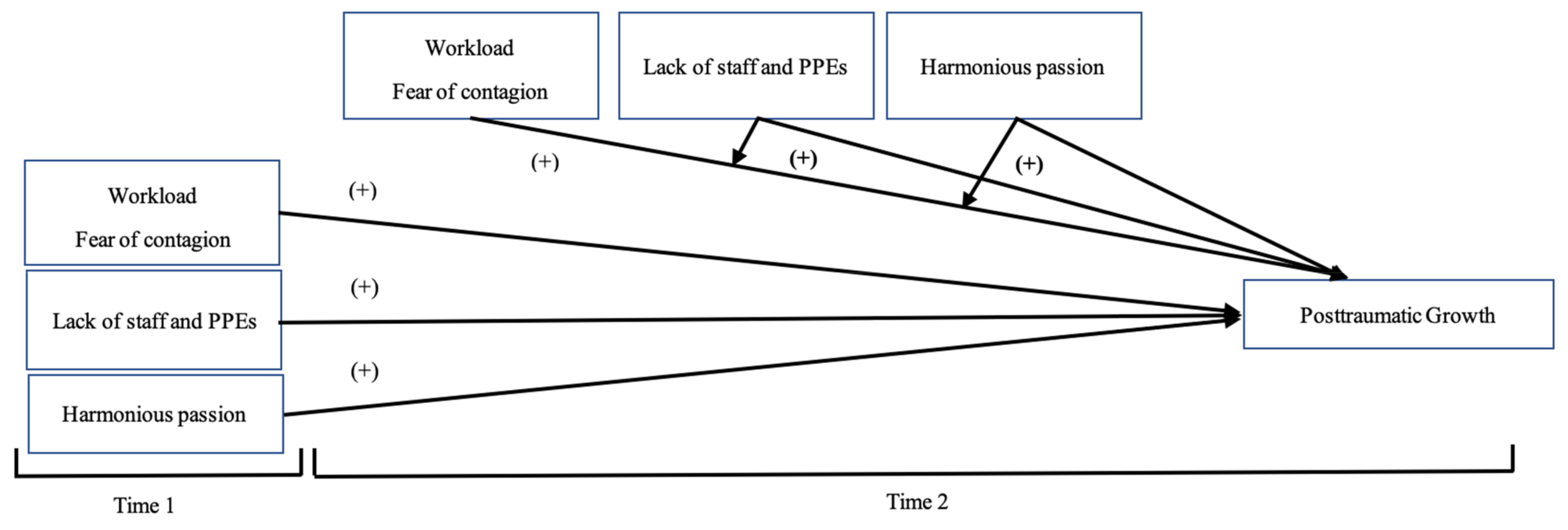

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

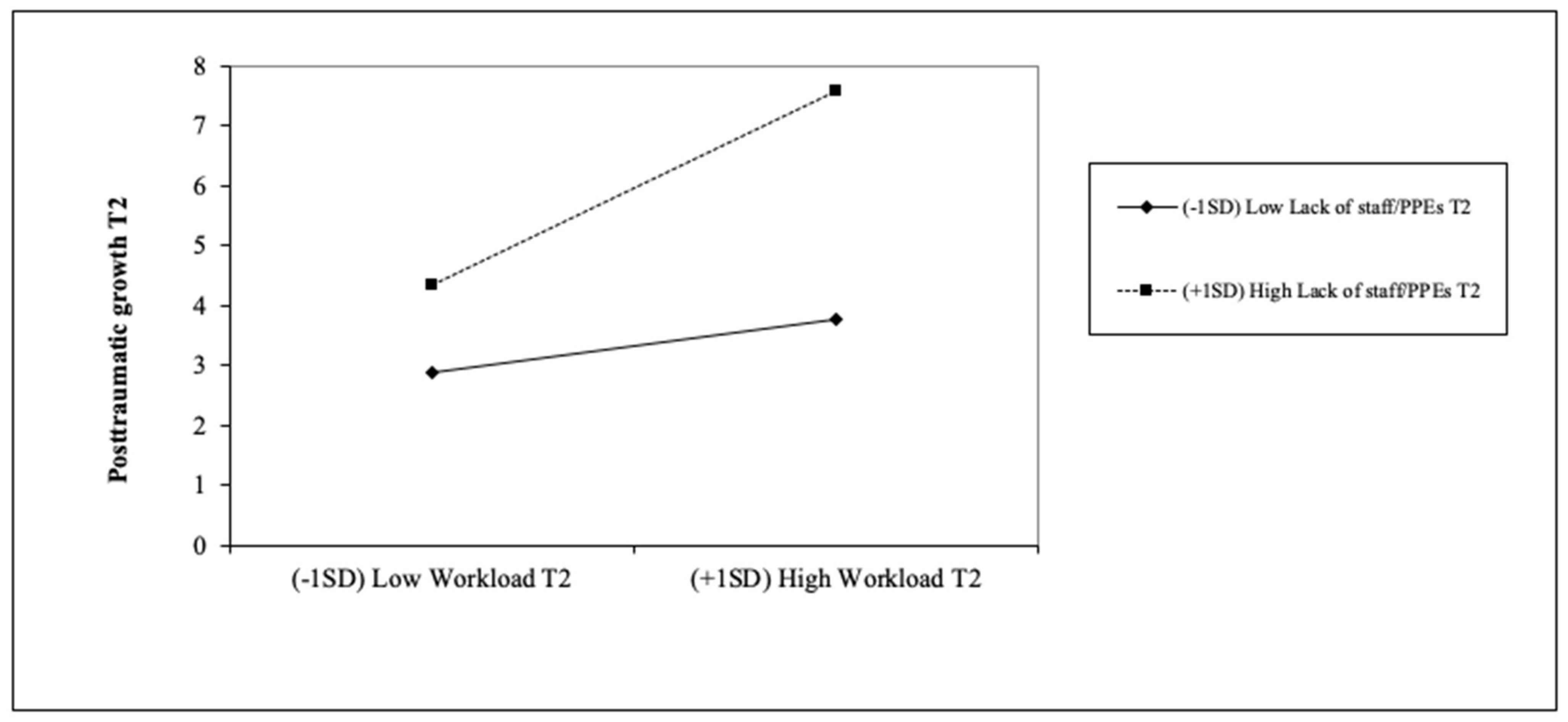

3.3. Interaction Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report 209. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200816-covid-19-sitrep-209.pdf?sfvrsn=5dde1ca2_2 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Secosan, I.; Virga, D.; Crainiceanu, Z.P.; Bratu, T. The Mediating Role of Insomnia and Exhaustion in the Relationship between Secondary Traumatic Stress and Mental Health Complaints among Frontline Medical Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Martínez-López, J.; Ángel; Gómez-Galán, J.; López-Meneses, E. Anxiety about the Risk of Death of Their Patients in Health Professionals in Spain: Analysis at the Peak of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londoño-Ramírez, A.; García-Pla, S.; Bernabeu-Juan, P.; Pérez-Martínez, E.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; Hofstadt-Román, C.V.-D. Impact of COVID-19 on the Anxiety Perceived by Healthcare Professionals: Differences between Primary Care and Hospital Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-López, J.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Galán, J. Burnout among Direct-Care Workers in Nursing Homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Preventive and Educational Focus for Sustainable Workplaces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfante, A.; Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Castelli, L. Traumatic Stress in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Immediate Impact. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavera-Velasco, B.; García-Albuerne, Y.; Martín-García, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumello, C.; Bramanti, S.M.; Ballarotto, G.; Candelori, C.; Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Crudele, M.; Lombardi, L.; Pignataro, S.; Viceconti, M.L.; et al. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornell, F.; Halpern, S.C.; Kessler, F.H.P.; Narvaez, J.C.D.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00063520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Análisis de los casos de COVID-19 en personal sanitario notificados a la RENAVE hasta el 10 de mayo en España. 2020. Available online: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/Enf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Maslach, C. Job Burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Broome, M.E.; Ning, C. The performance and professionalism of nurses in the fight against the new outbreak of COVID-19 epidemic is laudable. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 107, 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Athanasiou, N.; Sakkas, N.; Patrinos, S.; Sakka, E.; Barmparessou, Z.; Tsikrika, S.; Adraktas, A.; Pataka, A.; Migdalis, I.; et al. From Recession to Depression? Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Anxiety, Traumatic Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, E.M.; Pedroli, E.; D’Aniello, G.E.; Badiale, C.S.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manna, C.; Badiale, M.S.; Riva, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Molinari, E. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrù, G.; Marzetti, F.; Conversano, C.; Vagheggini, G.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Panait, E.; Gemignani, A. Secondary Traumatic Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Figley, C.R., Ed.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, J.E.; Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Chico-Fernández, M.; Hofheinz, S.B.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. The Job Demands and Resources Related to COVID-19 in Predicting Emotional Exhaustion and Secondary Traumatic Stress among Health Professionals in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 564036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, J. Ángel; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Galán, J.; Fernández-Martínez, M.D.M. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Emergency on Health Professionals: Burnout Incidence at the Most Critical Period in Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; De Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Navarro-Abal, Y.; López-López, M.J.; Romero-Martín, M.; Climent-Rodríguez, J.A. Engagement, Passion and Meaning of Work as Modulating Variables in Nursing: A Theoretical Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, E.G.; Forest, J.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lemyre, P.-N.; Crevier-Braud, L.; Bergeron, É. Passion for Work and Emotional Exhaustion: The Mediating Role of Rumination and Recovery. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2012, 4, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Jiménez, J.E.; Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Chico-Fernández, M.; Montejo, J.C.; Garrosa, E. The Moderator Role of Passion for Work in the Association between Work Stressors and Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Cross-Level Diary Study among Health Professionals of Intensive Care Units. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlfort, N.; Philippe, F.L.; Vallerand, R.J.; Ménard, J. On passion and heavy work investment: Personal and organizational outcomes. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 29, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, P.; Forest, J.; Courcy, F. From strengths use to work performance: The role of harmonious passion, subjective vitality, and concentration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.M.; Ho, V.T.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Kirkman, B.L. Passion at work: A meta-analysis of individual work outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, J.; Mageau, G.A.; Sarrazin, C.; Morin, E.M. “Work is my passion”: The different affective, behavioural, and cognitive consequences of harmonious and obsessive passion toward work. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2010, 28, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliani, R.; Purba, D.E. The Mediating Role of Passion for Work on the Relationship between Task Significance and Performance. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2019, 27, 1945–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Amarnani, R.K.; Lajom, J.A.L.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Capezio, A. Consumed by obsession: Career adaptability resources and the performance consequences of obsessive passion and harmonious passion for work. Hum. Relat. 2019, 73, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhova, M.N.; Ho, V.T. Chameleonic obsessive job passion: Demystifying the relationships between obsessive job passion and in-role and extra-role performance. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, G.L.; Forest, J.; Crevier-Braud, L. Passion at work and burnout: A two-study test of the mediating role of flow experiences. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 21, 518–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Paquet, Y.; Philippe, F.L.; Charest, J. On the Role of Passion for Work in Burnout: A Process Model. J. Pers. 2010, 78, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest, J.; Mageau, G.A.; Crevier-Braud, L.; Bergeron, É.; Dubreuil, P.; Lavigne, G.L. Harmonious passion as an explanation of the relation between signature strengths’ use and well-being at work: Test of an intervention program. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1233–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Castro, M.; Barrientos Delgado, J.; Avarado Ricci, E.; Páez Rovira, D. Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. TARGET ARTICLE: “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence”. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, J.; Jen, H.; Kang, X.L.; Kao, C.; Chou, K. A Large-Scale Survey on Trauma, Burnout, and Posttraumatic Growth among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzaki, A.E.; Tamiolaki, A.; Rovithis, M. The healthcare professionals amidst COVID-19 pandemic: A perspective of resilience and posttraumatic growth. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, A.; Castelli, L.; Franco, P. The Effect of COVID-19 on Radiation Oncology Professionals and Patients with Cancer: From Trauma to Psychological Growth. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 5, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.T.; Astakhova, M.N. Disentangling passion and engagement: An examination of how and when passionate employees become engaged ones. Hum. Relat. 2017, 71, 973–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, G.L.; Forest, J.; Fernet, C.; Crevier-Braud, L. Passion at work and workers’ evaluations of job demands and resources: A longitudinal study. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, R.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez, A.; Arias, E.; Palomera, A. Validación mexicana de la Escala de Estrés Traumático Secundario. Psicol. Salud 2011, 21, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Fernández, M.J.; Boada-Grau, J.; Gil-Ripoll, C.; Vigil-Colet, A. Spanish adaptation of the Passion toward Work Scale (PTWS). An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A.; Sharma, G. The Relationship between Faculty Members’ Passion for Work and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 20, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalewski, B.; Palka, L.; Kiczmer, P.; Sobolewska, E. The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak on the Polish Dental Community’s Standards of Care—A Six-Month Retrospective Survey-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.M.; Montoy, J.C.C.; Hoth, K.F.; Talan, D.A.; Harland, K.K.; Eyck, P.T.; Mower, W.; Krishnadasan, A.; Santibanez, S.; Mohr, N.; et al. COVID-19-Related Stress Symptoms Among Emergency Department Personnel. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Giannakoulis, V.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Author reply–Letter to the editor “The challenges of quantifying the psychological burden of COVID-19 on healthcare workers”. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic and Occupational Data | Total Health Professionals (N = 172) | |

|---|---|---|

| Categorical sociodemographic variables | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 | 16.9 |

| Female | 143 | 83.1 |

| Sentimental Relationship | ||

| With a relationship | 132 | 76.7 |

| Without a relationship | 40 | 23.3 |

| Quantitative sociodemographic variables | M | SD |

| Age | 38.09 | 10.67 |

| Job Position | ||

| Physician | 35 | 20.3 |

| Nurse | 48 | 27.9 |

| Nurse aides | 46 | 26.7 |

| Occupational therapist | 5 | 2.9 |

| Psychologist | 16 | 9.3 |

| Social workers | 13 | 7.6 |

| Physiotherapist | 9 | 5.2 |

| Categorical occupational variables | ||

| Centre | ||

| Hospitals and health centers | 64 | 37.2% |

| Nursing homes | 108 | 62.8% |

| Contact with COVID-19 patient | ||

| Yes | 57 | 33.1 |

| No | 7 | 4.1 |

| Missing Values | 64 | 62.8 |

| Quantitative occupational variables | ||

| Years of experience in the field | 17.92 | 11.48 |

| Variables | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Workload T1 a | 3.13 | 0.49 | 0.80 | - | 0.27 ** | 0.41 ** | −0.01 | 0.42 ** | 0.33** | 0.03 | 0.17 * | −0.16 * | 0.29 ** | −0.03 |

| 2. Fear of contagion T1 a | 2.74 | 0.76 | 0.80 | - | 0.49 ** | −0.05 | 0.37 ** | 0. 16 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.05 | 0.24 ** | 0.17 ** | |

| 3. Lack of staff and PPE T1 a | 3.16 | 0.73 | 0.68 | - | −0.09 * | 0.45 ** | 0.11 | 0.31** | 0.29 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.05 | ||

| 4. Harmonious passion T1 b | 5.09 | 1.20 | 0.68 | - | −0.22 ** | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.49 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.08 | |||

| 5. STS T1 a | 2.70 | 0.45 | 0.84 | - | 0.24 ** | 0.12 | 0.19 * | −0.26 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.04 | ||||

| 6. Workload T2 a | 3.18 | 0.50 | 0.73 | - | 0.17 * | 0.27 ** | −0.11 | 0.41 ** | 0.04 | |||||

| 7. Fear of contagion T2 a | 2.56 | 0.76 | 0.80 | - | 0.37 ** | −0.07 | 0.33 ** | 0.19 * | ||||||

| 8. Lack of staff and PPE T2 a | 2.70 | 0.83 | 0.72 | - | −0.12 | 0.36 ** | 0.08 | |||||||

| 9. Harmonious passion T2 b | 5.07 | 1.17 | 0.69 | - | −0.38 ** | 0.14 | ||||||||

| 10. STS T2 a | 2.78 | 0.42 | 0.82 | - | 0.12 | |||||||||

| 11. Posttraumatic growth T2 c | 4.11 | 0.84 | 0.80 | - |

| Variables | Time | Sex | Centre | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2T1 | t | males | females | t | H&HC | NH | t | |

| 1. Workload a | 0.053 | 1.228 | 2.972 | 3.229 | −2.559 ** | 3.137 | 3.215 | −0.958 |

| 2. Fear of contagion a | −0.180 | −3.007 ** | 2.310 | 2.617 | −2.178 * | 2.635 | 2.524 | 0.923 |

| 3. Lack of staff and PPE a | −0.456 | −6.414 *** | 2.500 | 2.741 | −1.450 | 2.570 | 2.777 | −1.625 |

| 4. Harmonious passion b | −0.022 | −0.237 | 4.942 | 5.098 | −0.783 | 5.250 | 4.972 | 1.451 |

| 5. STS a | 0.074 | 2.439 ** | 2.595 | 2.818 | −2.671 ** | 2.699 | 2.827 | −1.813 |

| 6. Posttraumatic Growth | − | − | 4.155 | 4.095 | 0.416 | 3.747 | 4.307 | −3.834 *** |

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Traumatic Stress | Posttraumatic Growth | |||||||

| Step 1: Control | Standardized β | Standardized β | ||||||

| Sex | 0.084 | 0.106 | 0.050 | 0.039 | −0.054 | −0.069 | −0.103 | −0.069 |

| Centre | 0.091 | 0.067 | 0.051 | 0.055 | 0.349 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.399 *** |

| STS T1 | 0.534 *** | 0.490 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.410 *** | − | − | − | − |

| Step 2: variables T1 | ||||||||

| Workload | 0.054 | −0.001 | −0.009 | −0.065 | −0.089 | −0.023 | ||

| Fear contagion | 0.081 | 0.038 | 0.057 | 0.183 * | 0.214 ** | 0.182 | ||

| Lack staff/PPE | −0.012 | 0.013 | 0.002 | −0.145 | −0.109 | −0.089 | ||

| Harmonious passion | −0.123 | −0.044 | −0.042 | 0.159 * | 0.065 | 0.054 | ||

| Step 3: variables T2 | ||||||||

| Workload | 0.203 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.007 | 0.027 | ||||

| Fear contagion | 0.187 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.241 ** | ||||

| Lack staff/PPE | 0.130 * | 0.119 | −0.053 | −0.026 | ||||

| Harmonious passion | −0.195 ** | −0.192 ** | 0.191 * | 0.210 * | ||||

| Step 4: Moderations T2 | ||||||||

| Workload × Lack staff/PPE | 0.017 | 0.184 * | ||||||

| Fear contagion × Lack staff/PPE | 0.066 | −0.117 | ||||||

| Workload × harmonious passion | 0.046 | −0.077 | ||||||

| Fear contagion × harmonious passion | −0.041 | 0.084 | ||||||

| 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.22 | |

| 0.32 *** | 0.01 | 0.16 *** | −0.03 | 0.11 *** | 0.04 * | 0.05 ** | 0.02 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno-Jiménez, J.E.; Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Demerouti, E.; Belda Hofheinz, S.; Chico-Fernández, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. The Role of Healthcare Professionals’ Passion in Predicting Secondary Traumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Growth in the Face of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094453

Moreno-Jiménez JE, Blanco-Donoso LM, Demerouti E, Belda Hofheinz S, Chico-Fernández M, Moreno-Jiménez B, Garrosa E. The Role of Healthcare Professionals’ Passion in Predicting Secondary Traumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Growth in the Face of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094453

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Jiménez, Jennifer E., Luis Manuel Blanco-Donoso, Evangelia Demerouti, Sylvia Belda Hofheinz, Mario Chico-Fernández, Bernardo Moreno-Jiménez, and Eva Garrosa. 2021. "The Role of Healthcare Professionals’ Passion in Predicting Secondary Traumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Growth in the Face of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094453

APA StyleMoreno-Jiménez, J. E., Blanco-Donoso, L. M., Demerouti, E., Belda Hofheinz, S., Chico-Fernández, M., Moreno-Jiménez, B., & Garrosa, E. (2021). The Role of Healthcare Professionals’ Passion in Predicting Secondary Traumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Growth in the Face of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094453