Humanness Is Not Always Positive: Automatic Associations between Incivilities and Human Symbols

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

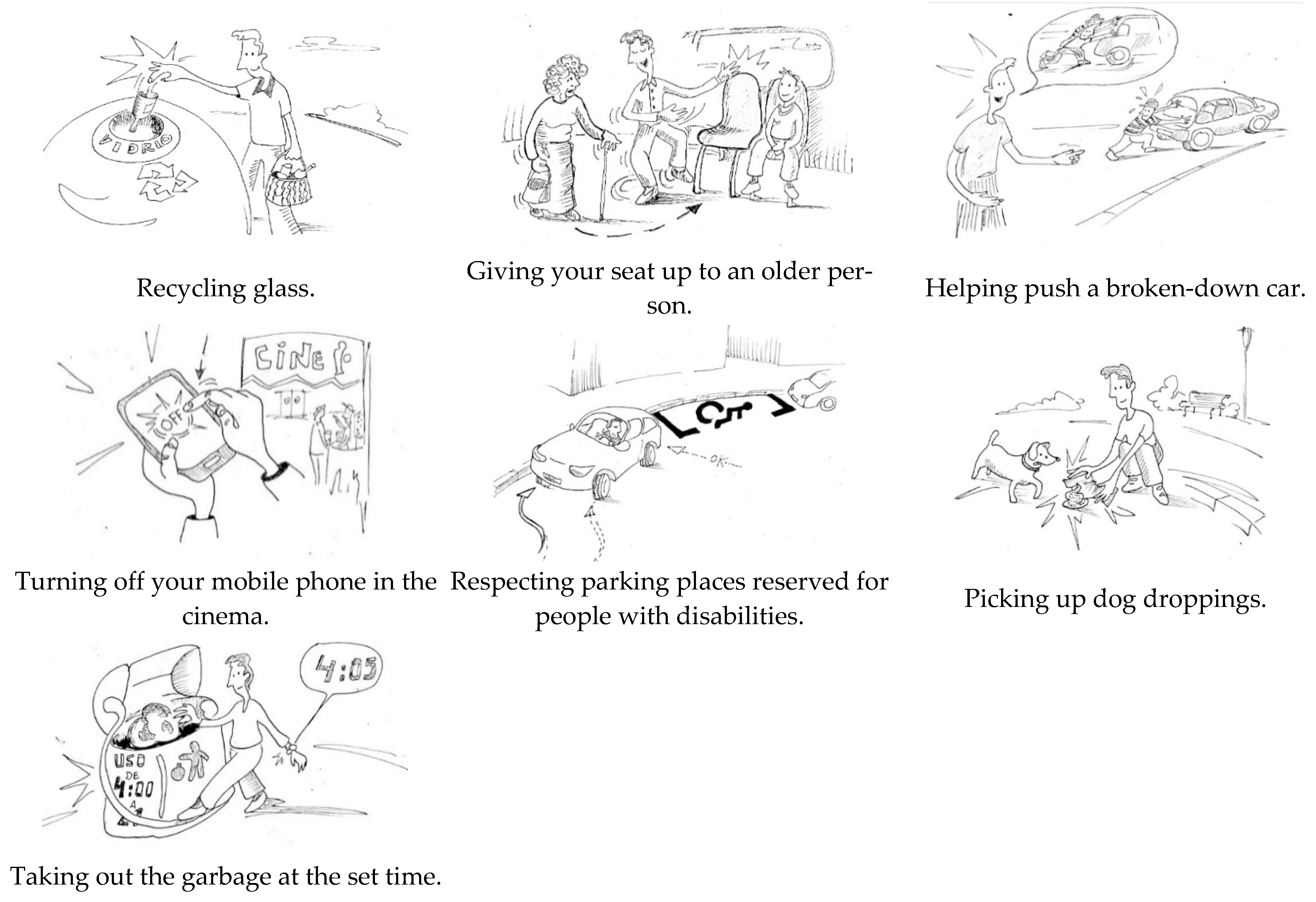

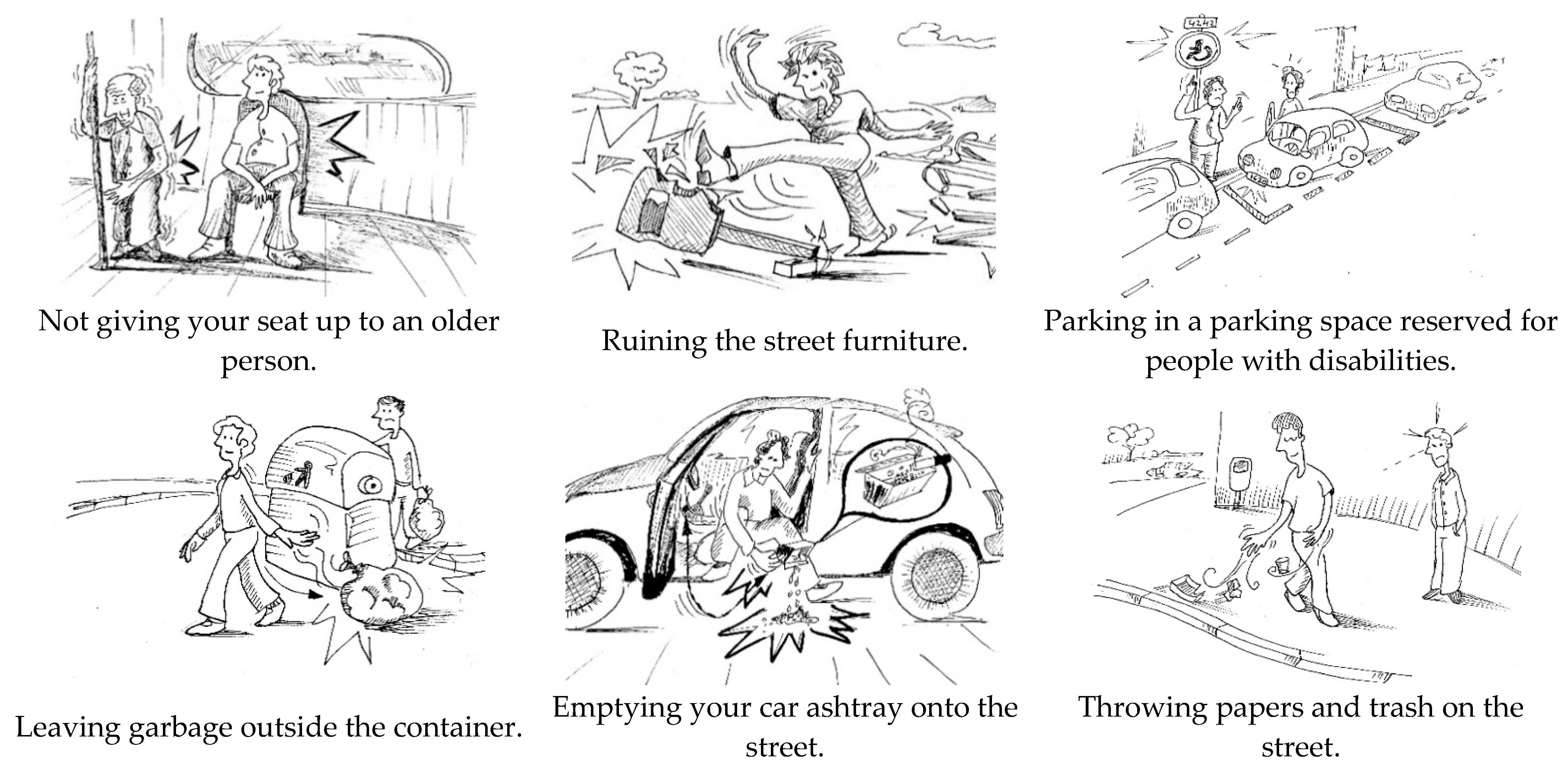

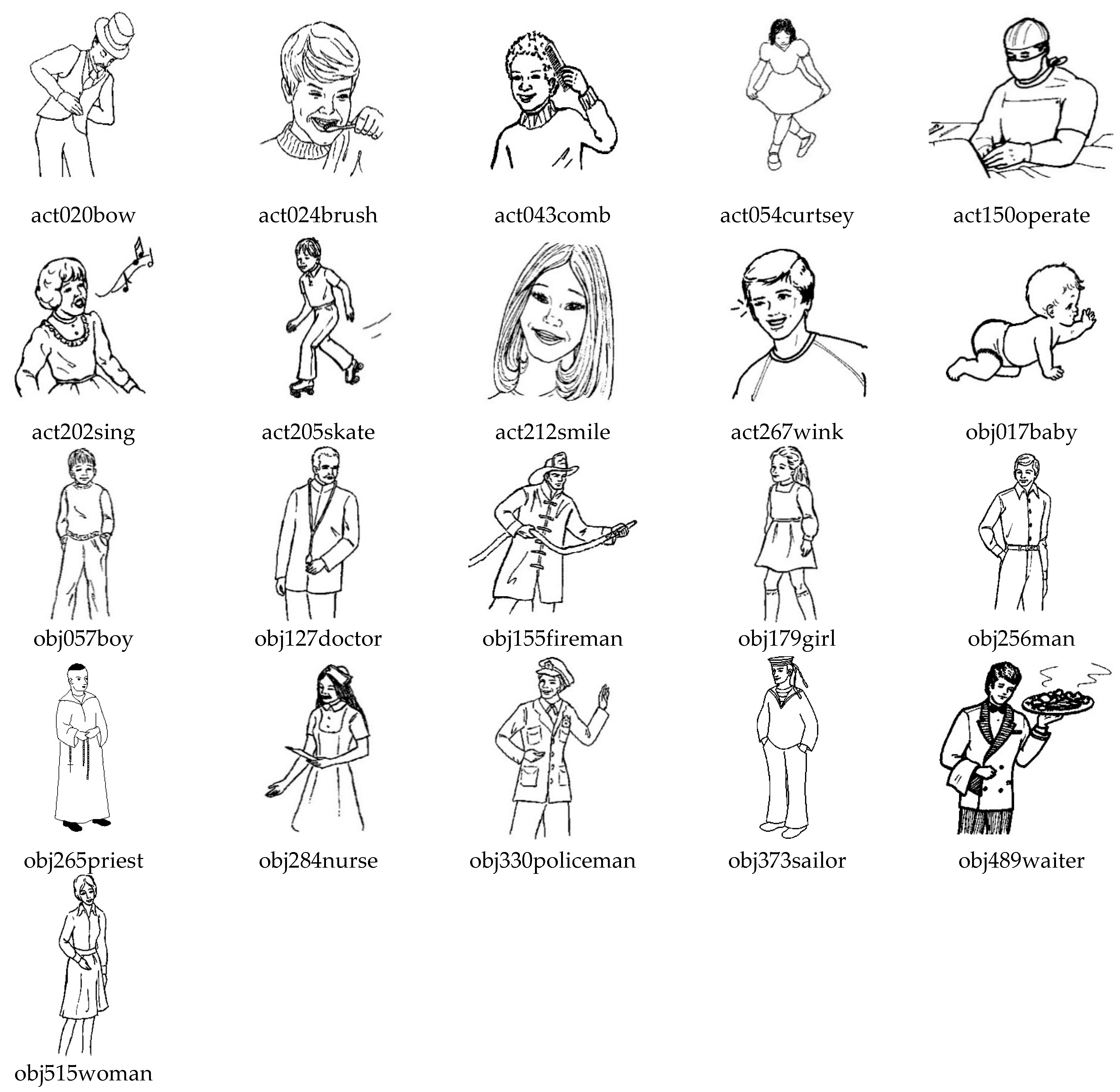

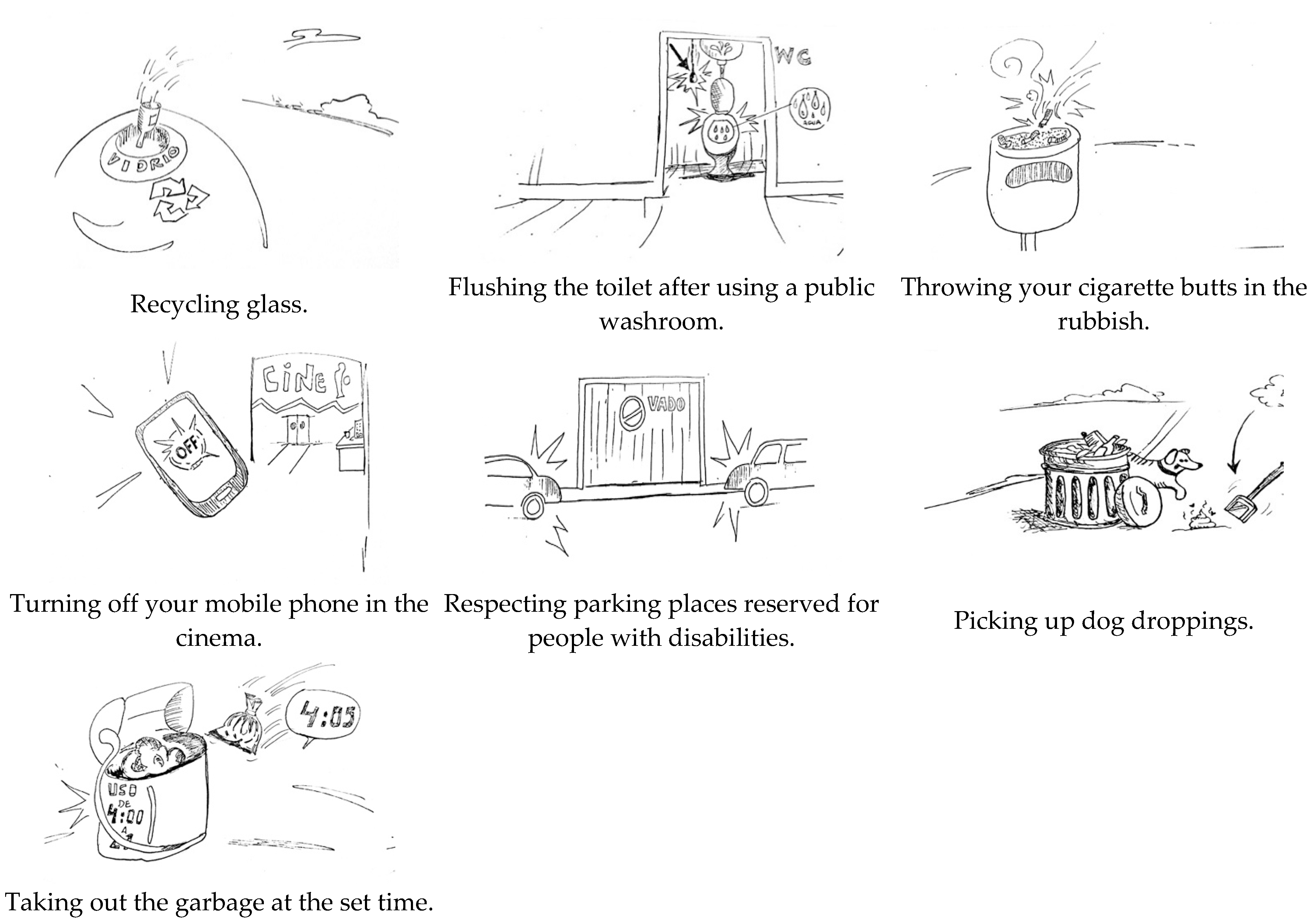

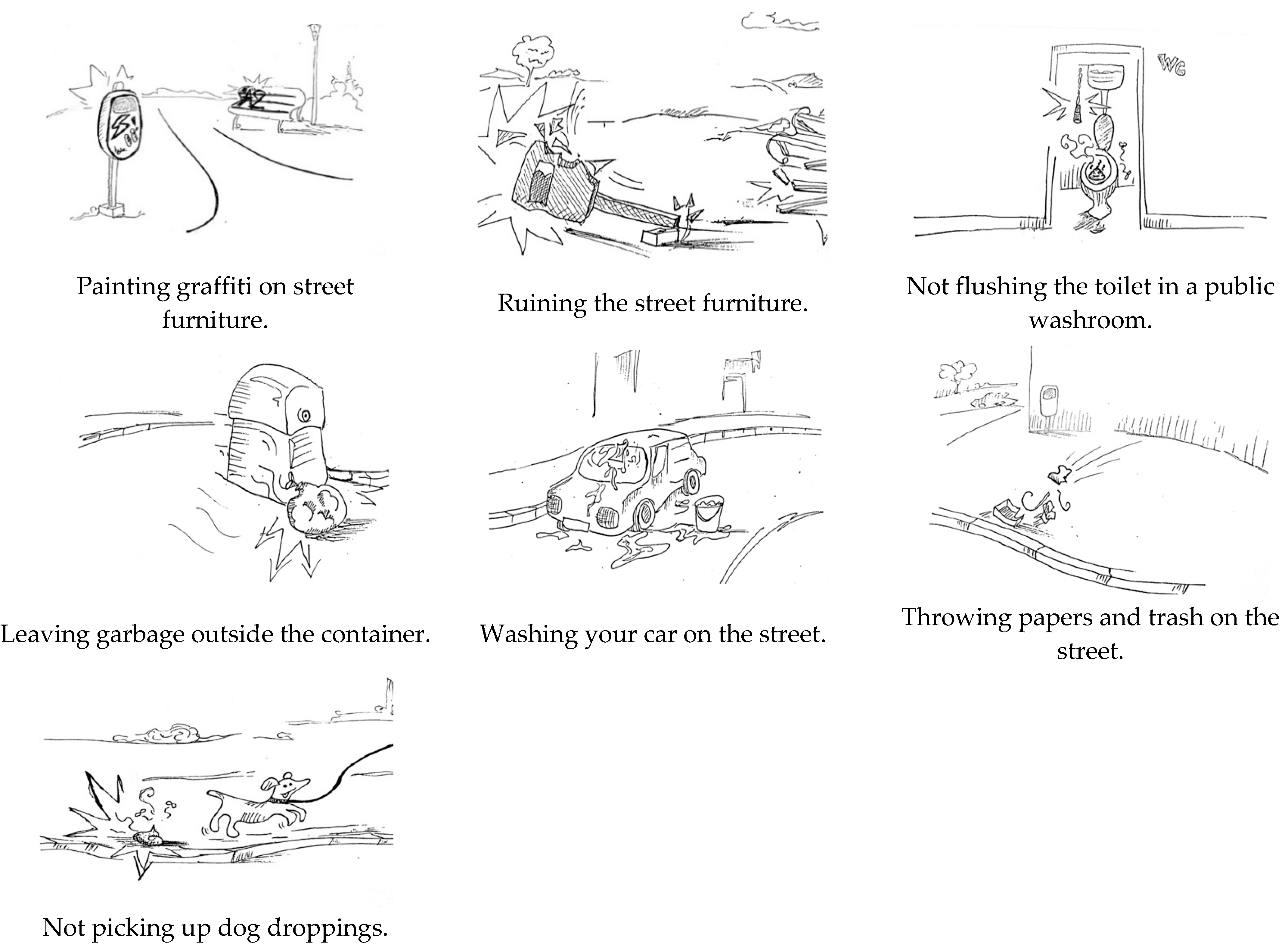

2.1.2. Materials

2.1.3. Procedure

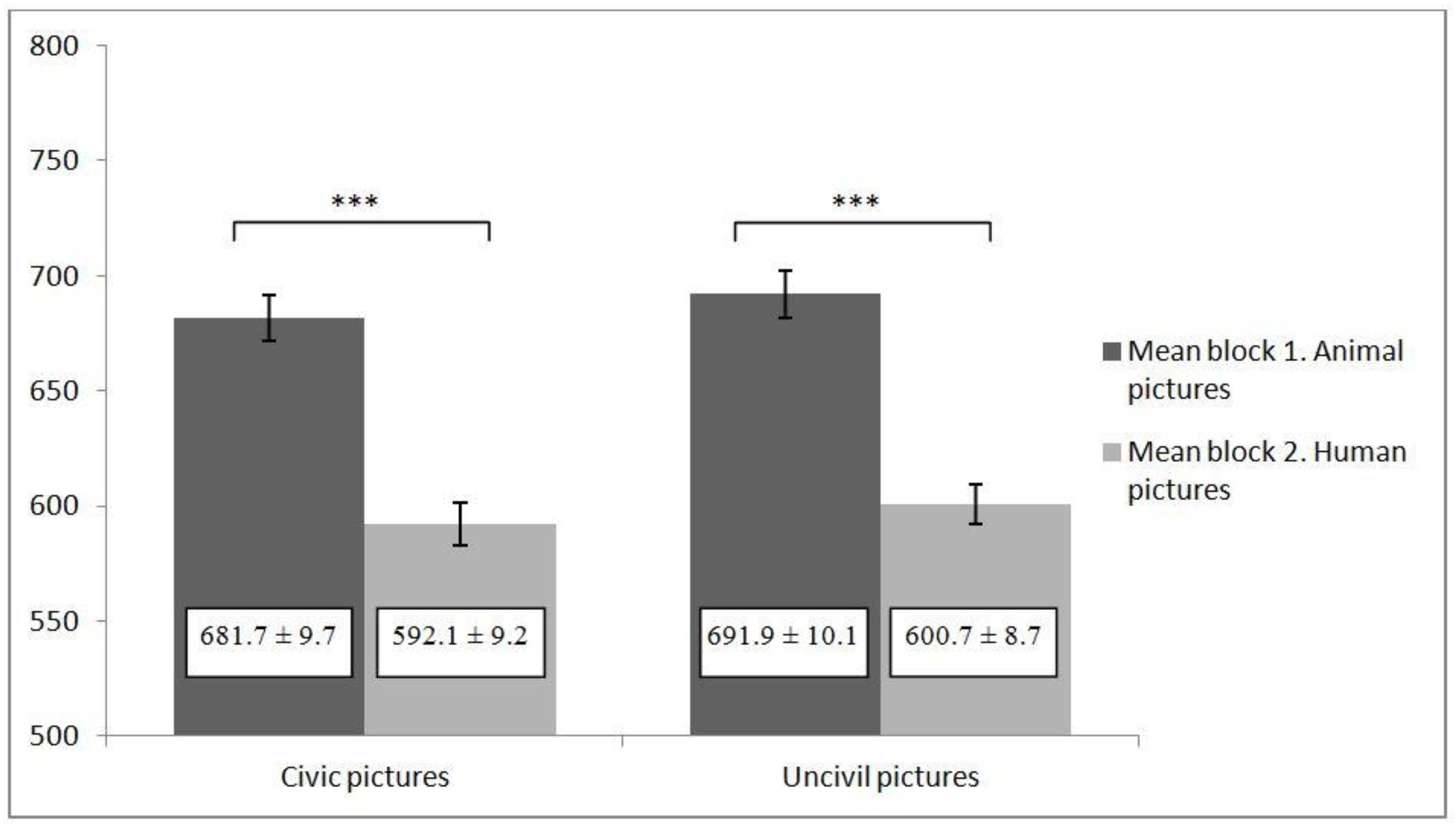

2.2. Results

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

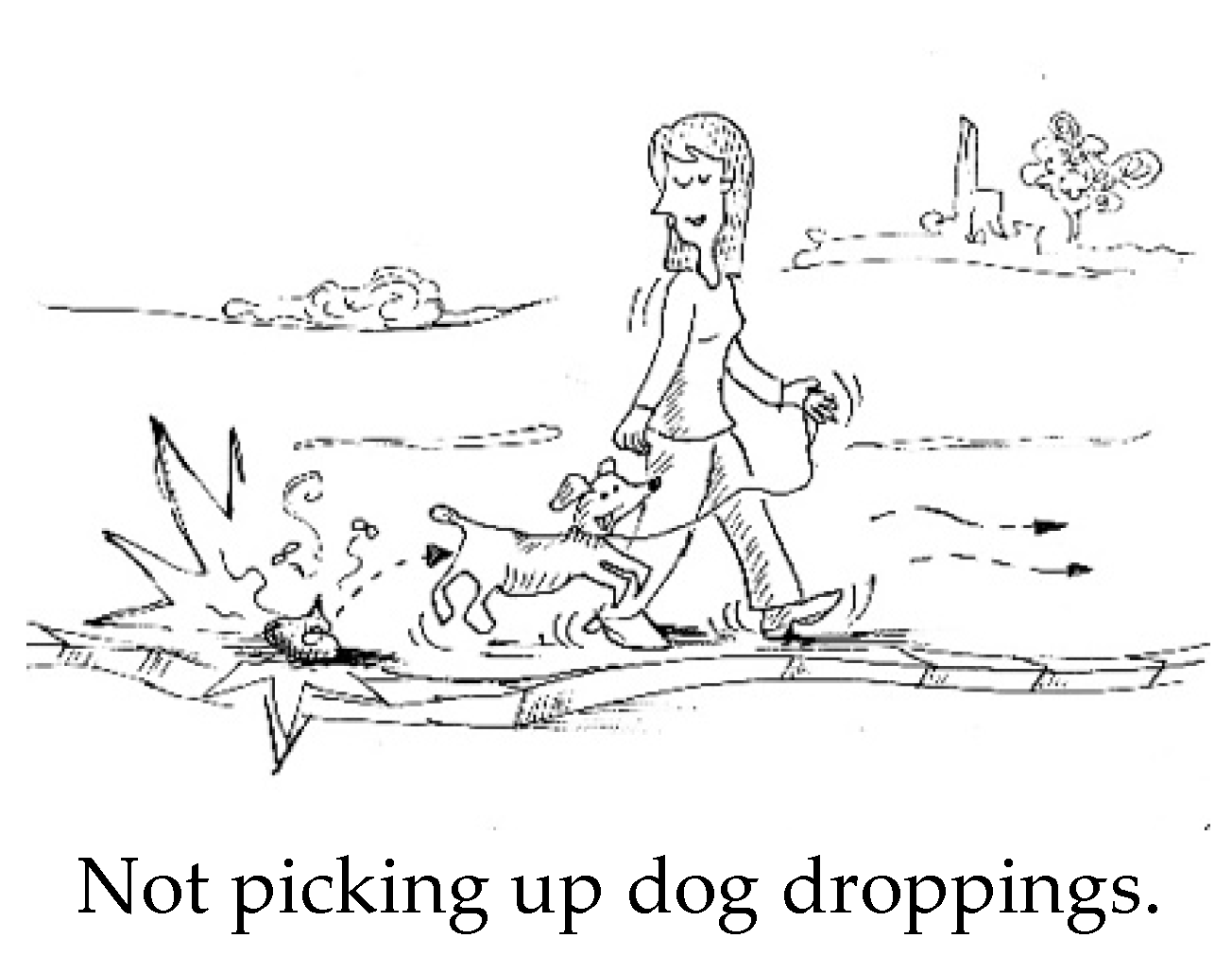

3.1.2. Materials

3.1.3. Procedure

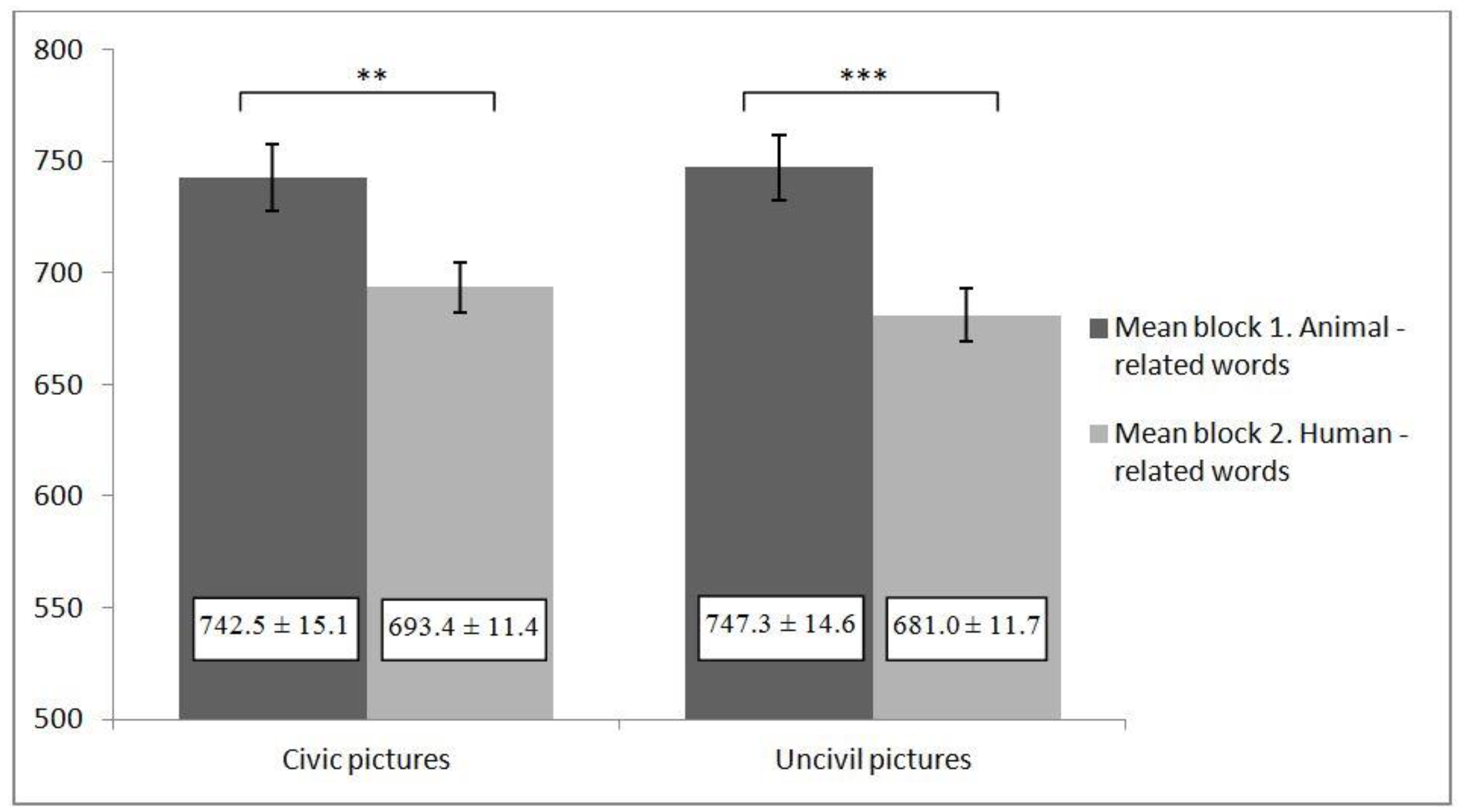

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Materials

4.1.3. Procedure

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. General Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

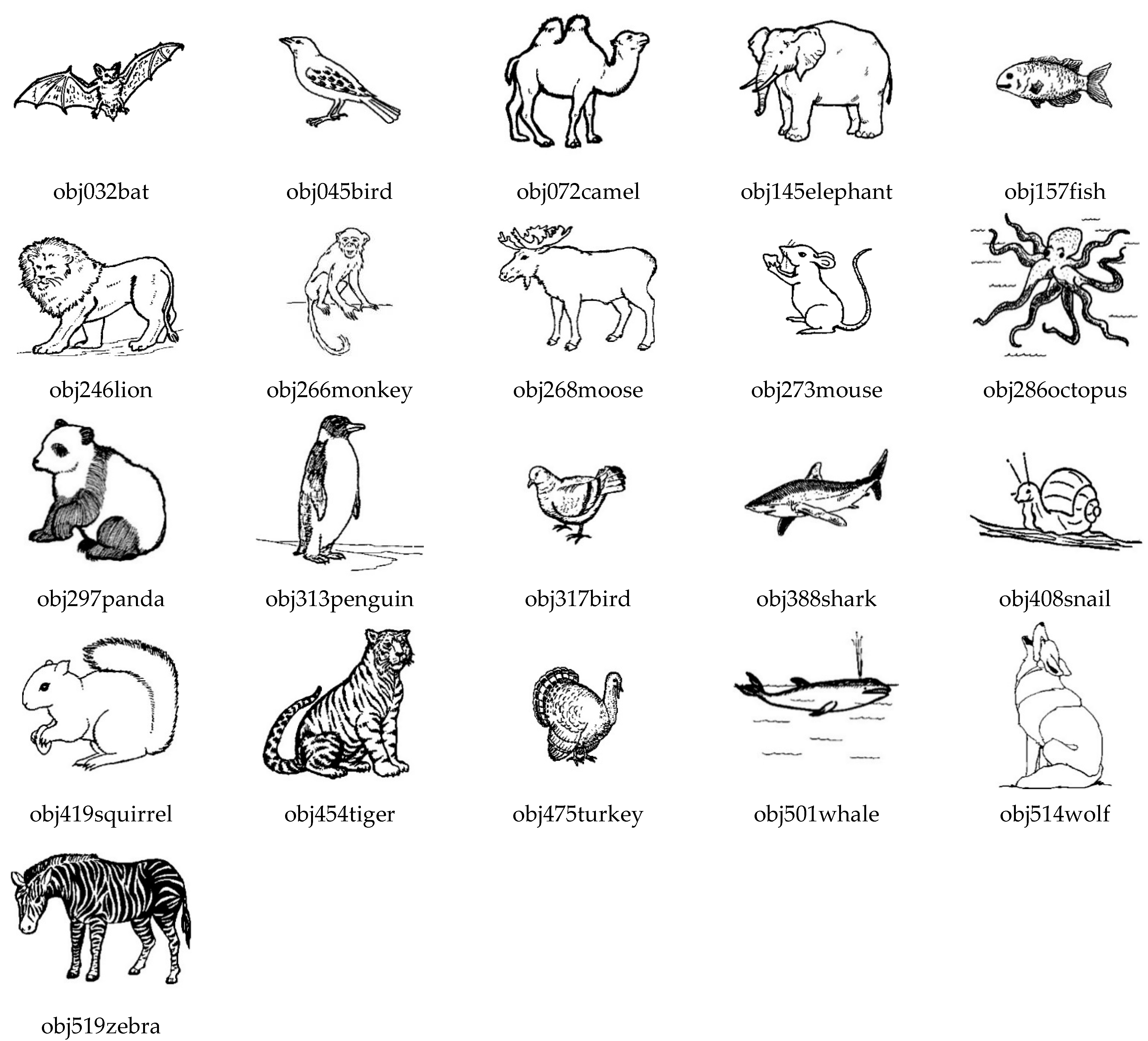

| PALABRAS ANIMALES | ANIMAL WORDS | PALABRAS HUMANAS | HUMAN WORDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jaula | Cage | Mafia | Mafia |

| 2 | Bestia | Beast | Prisión | Prison |

| 3 | Picadura | Bite | Censura | Censure |

| 4 | Bicho | Bug | Grito | Scream |

| 5 | Estiércol | Manure | Divorcio | Divorce |

| 6 | Pezuña | Hoof | Condena | Sentence |

| 7 | Rugido | Roar | Maquillaje | Makeup |

| 8 | Corral | Corral | Peluca | Wig |

| 9 | Rumiante | Ruminant | Bandera | flag |

| 10 | Cuadra | Stable | Símbolo | Symbol |

| 11 | Hocico | Neb | Parlamento | Parliament |

| 12 | Garra | Claw | Pandilla | Gang |

| 13 | Granja | Farm | Sindicato | Syndicate |

| 14 | Nido | Nest | Tradición | Tradition |

| 15 | Trompa | Horn | Congregación | Congregation |

| 16 | Mascota | Pet | Pie | Foot |

| 17 | Bandada | Flock | Gente | People |

| 18 | Alas | Wings | Matrimonio | Marriage |

| 19 | Fauna | Fauna | Ciudadano | Citizen |

| 20 | Cría | Calf | Persona | Person |

| 21 | Cachorro | Puppy | Equipo | Team |

Appendix D

References

- Durkheim, E. Les Règles de la Méthode Sociologique; Presse Universitaire de France: Paris, France, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, J. The Cement of Society: A Study of Social Order; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugier, A.; Chekroun, P.; Pierre, K.; Niedenthal, P.M. Group membership influences social control of perpetrators of uncivil behaviors. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments. In Groups, Leadership and Men; Guetzknow, H., Ed.; Carnegie Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1951; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M. The Psychology of Social Norms; Harper: Oxford, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, L.H. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory; Aldine Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Páramo, P. Comportamiento urbano responsable: Las reglas de convivencia en el espacio público. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2013, 45, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, P.M. Choosing Civility: The Twenty-Five Rules of Considerate Conduct; Palgrave Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chaurand, N.; Brauer, M. What determines social control? people’s reactions to counternormative behaviours in urban environments. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 1689–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.; Smith, P. Rethinking urban incivility research: Strangers, bodies and circulations. Urban. Stud. 2006, 43, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.; Smith, P. Everyday incivility: Towards a benchmark. Soc. Rev. 2003, 51, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.; Matheau-Police, A.; Couty, C. Development of a scale of perceived environmental annoyances in urban settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, A.; Morris, G.; Curtice, J.; Robertson, C.; Allardice, G.; Robertson, R. Associations between health and different types of environmental incivility: A Scotland-wide study. Public Health 2009, 123, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Qiu, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Wu, H. How incivility and academic stress influence psychological health among college students: The moderating role of gratitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, D.W.; Wilson, J.K.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Johnston, L.D. Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. Am. Soc. Rev. 1996, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisuc, A.; Brauer, M.; Fonseca, A.; Chaurand, N.; Greitemeyer, T. Individual differences in social control: Who ‘speaks up’ when witnessing uncivil, discriminatory, and immoral behaviors? Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J. Deviance, perceived responsibility, and negative peer reactions. Dev. Psychol. 1991, 27, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschetti, R. Ethical analysis in public health. Lancet 2002, 360, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; Loughnan, S. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; Bain, P.; Douge, L.; Lee, M.; Bastian, B. More human than you: Attributing humanness to self and others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, N.; Bastian, B.; Bissett, M. Essentialist beliefs about personality and their implications. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1661–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.M.; Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Dimensions of mind perception. Science 2007, 315, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Moral typecasting: Divergent perceptions of moral agents and moral patients. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Leidner, B.; Castano, E. Toward a comprehensive taxonomy of dehumanization: Integrating two senses of humanness, mind perception theory, and stereotype content model. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 213, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K. Moral transformation: Good and evil turn the weak into the mighty. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 1, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M.; Rotman, J.D.; Piazza, J. Perceiving the agency of harmful agents: A test of dehumanization versus moral typecasting accounts. Cognition 2016, 146, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, B.; Denson, T.F.; Haslam, N. The roles of dehumanization and moral outrage in retributive justice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Schein, C. Two minds vs. two philosophies: Mind perception defines morality and dissolves the debate between deontology and utilitarianism. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2012, 3, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Waytz, A.; Young, L. The moral dyad: A fundamental template unifying moral judgment. Psychol. Inq. 2012, 23, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Dimensions of moral emotions. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, A.; Küster, D. Robots as malevolent moral agents: Harmful behavior results in dehumanization, not anthropomorphism. Cogn. Sci. 2020, 44, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, A.L.; Raine, A. Psychopathy and instrumental aggression: Evolutionary, neurobiological, and legal perspectives. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2009, 32, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealey, L. Primary sociopathy (psychopathy) is a type, secondary is not. Behav. Brain Sci. 1995, 18, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, D. The role of the lie in the evolution of human language. Lang. Sci. 2017, 63, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, F.; Wiltermuth, S.S. Evil genius? How dishonesty can lead to greater creativity. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Chaurand, N. Descriptive norms, prescriptive norms, and social control: An intercultural comparison of people’s reactions to uncivil behaviors. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edyvane, D. incivility as dissent. Polit. Stud. 2020, 68, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H. Civil society and the duty to dissent. Int. J. Nonprofit Law 2011, 13, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Francis, L.; Prosser, M.; Cameron, J.E. Counterproductive work behavior as protest. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, M.; Branscombe, N. Forgiveness and collective guilt assignment to historical perpetrator groups depend on level of social category inclusiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T.A.; Postmes, T. What does it mean to be human? How salience of the human category affects responses to intergroup harm. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoulin, S.; Rodriguez-Torres, R.; Rodriguez-Perez, A.; Vaes, J.; Paladino, M.P.; Gaunt, R.; Leyens, J.P. Emotional prejudice can lead to infra-humanisation. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 15, 259–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viki, G.T.; Winchester, L.; Titshall, L.; Chisango, T.; Pina, A.; Russell, R. Beyond secondary emotions: The infrahumanization of outgroups using human-related and animal-related words. Soc. Cogn. 2006, 24, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosek, B.A.; Greenwald, A.G.; Banaji, M.R. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.; Judd, C.M.; Hirsh, H.K.; Blair, I.V. Awareness of implicit attitudes. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, A.; Steinman, R.B. The single category implicit association test as a measure of implicit social cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, L.; Delgado, N.; Betancor, V.; Rodríguez-Torres, R.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A. The Link between Civility and Dehumanization Theory, Under review.

- Bates, E.; D’Amico, S.; Jacobsen, T.; Székely, A.; Andonova, E.; Devescovi, A.; Wicha, N. Timed picture naming in seven languages. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2003, 10, 344–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formanowicz, M.; Goldenberg, A.; Saguy, T.; Pietraszkiewicz, A.; Walker, M.; Gross, J.J. Understanding dehumanization: The role of agency and communion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 77, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, J.K.; Singhapakdi, A. Comparing Thai and US businesspeople: Perceived intensity of unethical marketing practices, corporate ethical values, and perceived importance of ethics. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 29, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S.; Karasawa, M. Dehumanization in the judicial system: The effect of animalization and mechanization of defendants on blame attribution. In Proceedings of the 10th Asian Association of Social Psychology Biennial Conference, Cebu City, Philippines, 19–22 August 2015; pp. 256–267. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Minoru_Karasawa/publication/309698459_Dehumanization_in_the_judicial_system_The_effect_of_animalization_and_mechanization_of_defendants_on_blame_attribution/links/581d35be08aeccc08aecb9e7.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Vasiljevic, M.; Viki, G.T. Dehumanization, moral disengagement, and public attitudes to crime and punishment. In Humanness and Dehumanization; Bain, P.G., Vaes, J., Leyens, J.-P., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2013; pp. 129–146. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318793334_Dehumanization_moral_disengagement_and_public_attitudes_to_crime_and_punishment (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Vasquez, E.A.; Loughnan, S.; Gootjes-Dreesbach, E.; Weger, U. The animal in you: Animalistic descriptions of a violent crime increase punishment of perpetrator. Aggress. Behav. 2014, 40, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T. Accounting for everyday incivility: An Australian study. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2006, 41, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, D.; Handley, I.M. The time for doing is not the time for change: Effects of general action and inaction goals on attitude accessibility and attitude change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, A. Automaticity and the unconscious. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Fiske, S.T., Gilbert, D.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 228–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGrange, R.L.; Ferraro, K.F.; Supancic, M. Perceived risk and fear of crime: Role of social and physical incivilities. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1992, 29, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, D.; Parker, C.; Roper, S. Litter, gender and brand: The anticipation of incivilities and perceptions of crime prevalence. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitner, R.O.; Yu, M.; Brown, E. Making neighborhoods safer: Examining predictors of residents’ concerns about neighborhood safety. J. Environ. Psychol 2012, 32, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, N.E.; Haynes, S.H. Gendered fear of crime socialization: An extension of Akers’s social learning theory. Femin. Criminol. 2011, 6, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Pertegas, S.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J. Vulnerability and perceived insecurity in the public spaces of Barcelona. Psyecology 2017, 8, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science 2008, 322, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.E.; Bargh, J.A. Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science 2008, 322, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Target | Associative Words |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Civic and uncivil behaviors (human agent) | Animal vs. human pictures |

| Study 2 | Civic and uncivil behaviors (human agent) | Animal vs. human-related words |

| Study 3 | Civic and uncivil behaviors (not human agent) | Animal vs. human-related words |

| Study 1 (N = 59) | Study 2 (N = 51) | Study 3 (N = 67) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | Range | n (%) | M (SD) | Range | n (%) | M (SD) | Range | |

| Age | 19.51 (4.15) | 18–48 | 19.42 (3.04) | 17–40 | 20.09 (2.11) | 18–26 | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 48 (81.4) | 49 (86.3) | 55 (82.1) | ||||||

| Male | 11 (18.6) | 7 (13.7) | 12 (17.9) | ||||||

| Degree | |||||||||

| Psychology | 32 (54.2) | 24 (47.1) | 67 (100) | ||||||

| Social work | 37 (45.8) | 20 (39.2) | |||||||

| Nursing | 5 (9.8) | ||||||||

| Labor relations | 2 (3.9) | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Gómez, L.; Delgado, N.; Betancor, V.; Chen-Xia, X.J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A. Humanness Is Not Always Positive: Automatic Associations between Incivilities and Human Symbols. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084353

Rodríguez-Gómez L, Delgado N, Betancor V, Chen-Xia XJ, Rodríguez-Pérez A. Humanness Is Not Always Positive: Automatic Associations between Incivilities and Human Symbols. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084353

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Gómez, Laura, Naira Delgado, Verónica Betancor, Xing Jie Chen-Xia, and Armando Rodríguez-Pérez. 2021. "Humanness Is Not Always Positive: Automatic Associations between Incivilities and Human Symbols" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084353

APA StyleRodríguez-Gómez, L., Delgado, N., Betancor, V., Chen-Xia, X. J., & Rodríguez-Pérez, A. (2021). Humanness Is Not Always Positive: Automatic Associations between Incivilities and Human Symbols. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084353