“Blood for Blood”? Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation in the German Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Recruitment Procedure

- (a)

- Socio-demographic factors: Age, sex, education, employment, (household) income, religious confession, nationality, as well as family and partnership status were assessed by a socio-demographic questionnaire.

- (b)

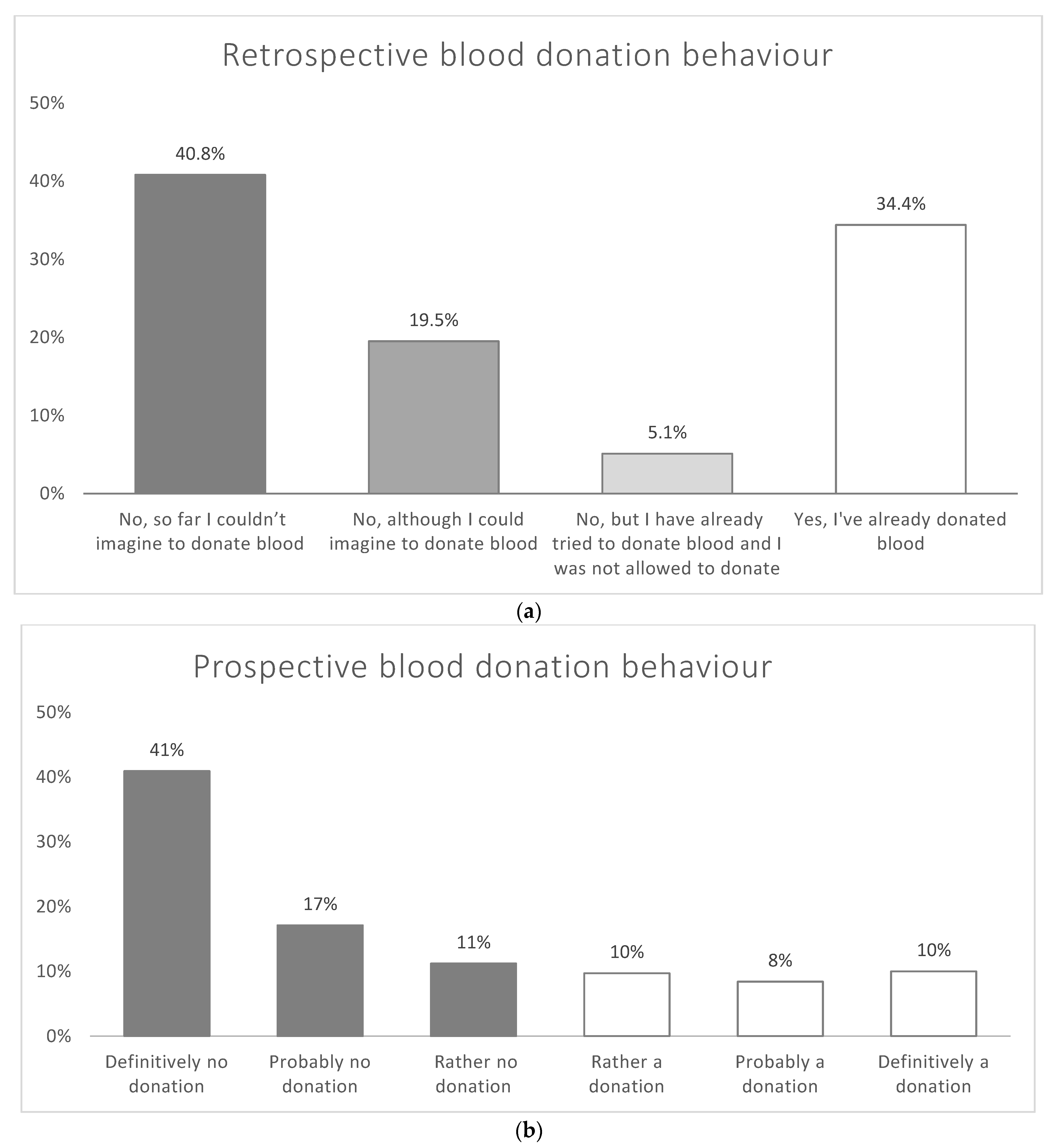

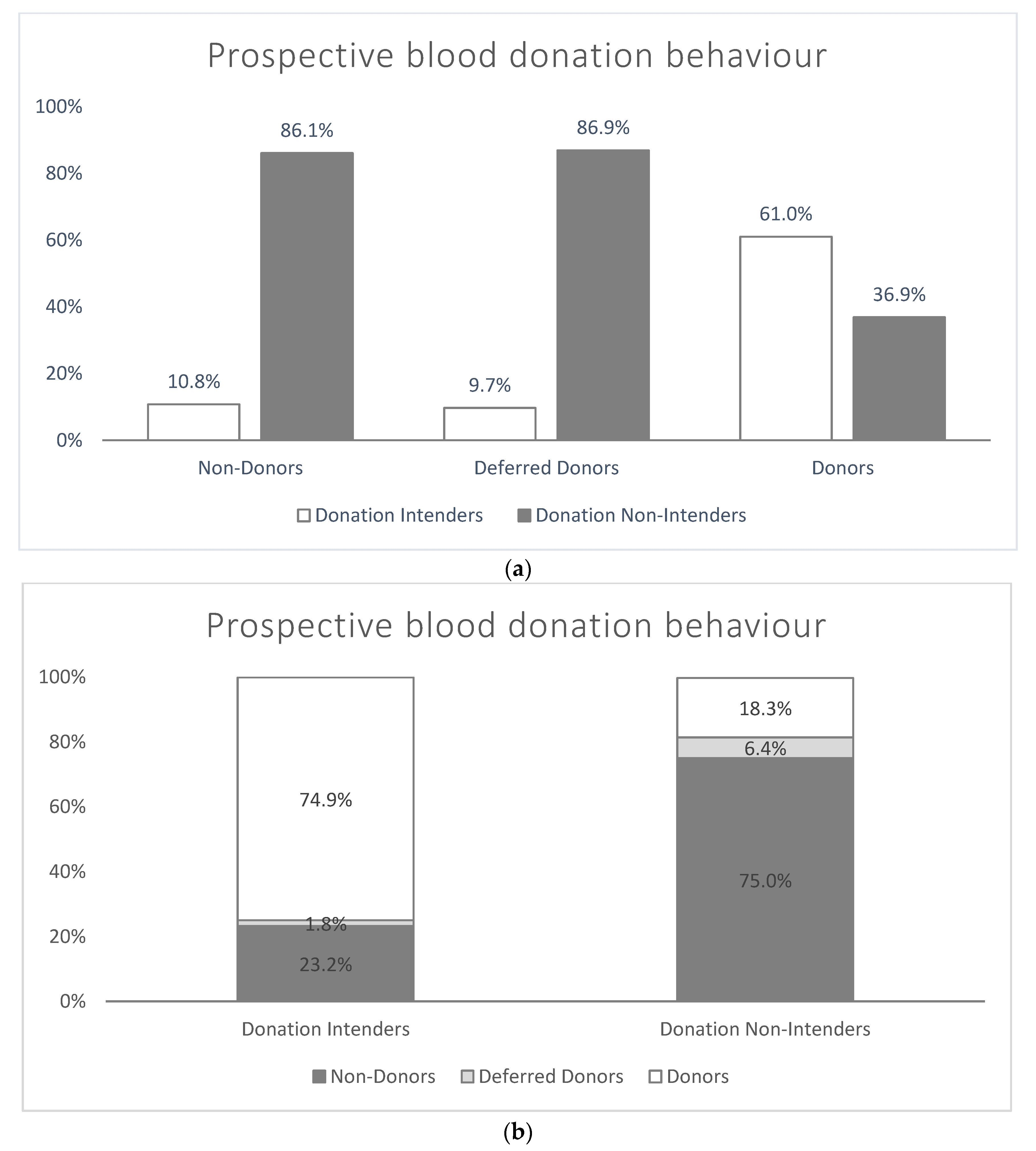

- Blood donation behaviour and intentions: Respondents were asked to decide whether they (1) did not, so far, imagine donating blood, (2) could imagine donating blood but did not manage to do so, (3) had already tried to donate blood but were deferred due to ineligibility, or (4) had already donated blood at least once in their lifetime (participants indicated which of these statements they agree with). Respondents who stated that they already had donated blood were referred to as “donors” (4), and the remaining respondents were referred to as “non-donors” (1 and 2) or deferred donors (3). The intention to donate blood within the next 12 months was assessed on a scale from 1 = “definitely not” to 6 = “definitely yes” (see Table A1 in Appendix A). We assigned the respondents according to their respective statements about future donation intentions to two different groups: respondents who intended to donate blood “rather”, “probably”, or “definitely yes” were referred to as “intenders”, respondents who intended to donate blood “rather not”, “probably not”, or “definitely not” were referred to as “non-intenders”.

- (c)

- The personal reasons (motives and deterrents) for donating blood were investigated with two open questions. The first question was: “Based on your answer, we would like you to describe in your own words, what, so far, your personal reasons were for donating or not donating blood in the past. Please try to answer this question as exactly as possible.” The second question was: “Based on your answer, we would like you to describe in your own words, what your personal reasons are for donating blood or not in the future. Please try to answer this question as exactly as possible.” Each open question was posed subsequently to the corresponding closed question to learn more about personal motives for (a) past (non-)donation behaviour or (b) future (non-)donation intention, respectively (see Table A1).

2.2. Coding Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Respondents

3.2. Prevalence of Blood Donation

3.3. Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation

3.3.1. Category Framework

- (1)

- “Ineligibility”: This domain contains all statements relating to reasons for the perceived inadequate suitability of blood donation. Statements were assigned to two categories, distinguishing between specific and unspecific reasons: (a) “specific reasons” include subcategories such as “age”, “health”, “pregnancy”, and “other” (e.g., “trips abroad”), whereas (b) “unspecific reasons” encompassed statements concerning a lack of “eligibility” without giving any specific reasons (e.g., “I am not eligible”).

- (2)

- “Impact and Effect”: This domain comprises all statements concerning the anticipated impact or effect of donating blood and contains three categories: (a) “physical consequences” encompasses expected positive physical effects (e.g., “I’m doing something good for myself, my body”), as well as negative physical effects (e.g., “my cardiovascular system can’t handle that”), and health risks; (b) “mental well-being” comprises both positive as well as negative psychological effects for the donor (e.g., “it’s (not) good for me”).

- (3)

- “Fear and Aversion”: This domain included two main categories. The first category, (a) “fear”, is again split into “fears in general”, i.e., without further specification (e.g., “I am afraid”) and four categories for specific fears, existing or anticipated “fear of needles”, “fear of blood”, “fear of pain”, and “fear to donate” (e.g., “I’m afraid of blood getting taken”). Any statements relating to specific other fears are assigned to the category “other fears” (e.g., “fear of doctors”). The second category is (b) “aversion”, which is subdivided into three subcategories concerning a personal aversion to “needles”, “blood”, or “other things”.

- (4)

- “Obstacles and Barriers”: This domain comprises all statements relating to possible logistical or organizational obstacles, assigned to the categories (a) “lack of information and knowledge” (e.g., “I wouldn’t even know where and how I could donate”), (b) “lack of possibilities or opportunities” (e.g., “no opportunity nearby”), (c) “organization/effort” involved (e.g., “too cumbersome, complicated”), and (d) “time/lack of time” (e.g., “I hardly have time for that”), or due to (e) “personal reasons”(e.g., “I can’t set it up”).

- (5)

- “Norms”: This domain consists of three core categories. First, (a) “reciprocity” is subdivided into four sub-categories. “General reciprocity” refers to statements concerning the recognition of the norm of reciprocity, because of past or possible future health care use (e.g., “blood for blood”). “Future-orientated reciprocity” is directed to the expectation of increasing the future possibility to receive someone else’s blood by donating blood (e.g., “a situation could come up in which one needs blood”). “Past-orientated (self) reciprocity” includes statements recognizing the norm of reciprocity because of having received someone else’s blood in the past (e.g., “to give back something I received”), whereas “past-orientated (friends and family) reciprocity” includes statements recognizing the norm of reciprocity because friends or family have received someone else’s blood (e.g., “in return for the blood my child received”). The second norm-based category, (b) “altruism”, consists of statements of the unconditional necessity of helping people (e.g., “that is the way in which I can save lives”). Third, (c) “feelings of obligation, social conscientiousness, and responsibility” is the general subjectively felt obligation and social norm or expectation to donate blood (e.g., “to do something for the community”). Other categories are (d) “religious beliefs”, including religious or denominational reasons, and (e) “personal beliefs”, including personal beliefs that are not covered by other normative beliefs (e.g., “it is important to me personally”). The category “important/necessary/meaningful/good cause” is concerned with a generally described relevance to donate blood “because it is important” because of a “vocational affiliation” (e.g., “through my work in the clinic”) or “surrendering responsibility”, addressing statements of existing insight of why individuals should become active (e.g., “enough others do it”), or because the personal need of one’s blood (e.g., “I need my blood myself”).

- (6)

- “Image and Experience”: This domain contains all statements that relate to specific images of or experiences with characteristics of blood donation. Respective categories are to “compensate for the lack of blood products/support the health care system” (e.g., “demand is constantly rising”), “lack of trust” due to media reports of fraud and profiteering (e.g., “because I don’t want to support such profiteering”), “no need present” (e.g., “There is no lack of blood”), or “rare blood type”—representing the knowledge of the rarity and thus the relevance of the donation (e.g., “important, I have a rare blood type”). Moreover, other categories are “advertisement campaign/phone call/appeal” (e.g., “promo day”), “(missing) previous experience or habit” (e.g., “I am a permanent donor and regularly donate blood”), “curiosity” (e.g., “I was curious”), or “absence of disadvantages” (e.g., “it doesn’t hurt me”).

- (7)

- “Benefits and Incentives”: This domain covers all motives mentioning compensatory measures. Respective types of motives cover a wide range of benefits and incentives; categories include (a) “blood donor card”, (b) “financial compensation”, (c) “determination of the blood type”, (d) “health check/screening” (free of charge), (e) “exemption from work/school”, as well as (f) “other services” including any other services or discount the donor receives (e.g., “extra holiday”).

- (8)

- “Conditions”: This domain comprises all statements of specific conditions in which blood donations would be given. This includes categories such as (a) “for personal need only” (e.g., “for myself alone”), (b) “only for family/important others/if person is known” (e.g., “why should I? if, then only for relatives”), or (c) “in case of a disaster/emergency/personal experience”, due to special demand or circumstances (e.g., “train accident”).

- (9)

- “Psychological aspects”: This domain comprises all statements related to attitudes, volition, and behaviour. It contains categories such as (a) “will be made up for/is planned”; (b) “not ready yet”; (c) “no interest/no will”; (d) “indifference/passivity/comfort”; (e) “not thought about it”; (f) “social aspect/peer group movement/personal influence and advice”, which contains statements of social motivation (e.g., “my ex-girlfriend took me there”); and (g) “refusal to donate blood”, addressing explanations due to the belief that blood donation is meaningless or not important.

- (10)

- “Missing points of contact”: This domain comprises all statements relating to missing triggers or contact points. It includes the categories (a) “no request/appellation/call”, which concerns the fact that the respondent has not explicitly been asked, called upon to donate, or addressed personally (e.g., “someone should ask me about it once”). Another reason may be a missing special occasion or reason to donate blood, encoded in the category (b) “missing reason/occasion” (e.g., “there hasn’t been an occasion to do it yet”). Finally, (c) “for no reason”, covers any statement where the respondents present a lack of awareness of their own motivations and obstacles.

3.3.2. Frequencies of Reasons

3.3.3. Frequencies of Deterrents

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Motives and Deterrents in Different (Non-)Donor Groups

4.3. Donation Behaviour in Different Groups

4.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Below Are a Few Questions Regarding the Topic of Blood Donation: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever donated blood? | No, so far I couldn’t imagine donating blood | □ |

| No, although I could imagine donating blood | □ | |

| No, but I have already tried donating blood and I was not allowed to donate | □ | |

| Yes, I’ve already donated blood | □ | |

| Based on your answer, we would like you to describe in your own words, what, so far, your personal reasons were for donating blood or not? Please try to answer this question as exactly as possible. ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Do you intent to donate blood within the next 12 months? | Definitively not | □ |

| Probably not | □ | |

| Rather not | □ | |

| Rather yes | □ | |

| Probably yes | □ | |

| Definitively yes | □ | |

| Based on your answer, we would like you to describe in your own words, what your personal reasons are for donating blood or not in the future? Please try to answer this question as exactly as possible. ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Total ** | Non-Donors | Deferred Donors | Donors | Donation- Non-Intenders | Donation Intenders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Have you ever donated blood? | ||||||||||||

| 1032 | 40.8 | 1032 | 67.7 | - | - | - | - | 963 | 55.0 | 32 | 4.5 |

| 494 | 19.5 | 494 | 32.3 | - | - | - | - | 350 | 20.0 | 133 | 18.8 |

| 130 | 5.1 | - | - | 130 | 100.0 | - | - | 113 | 6.4 | 13 | 1.8 |

| 870 | 34.4 | - | - | - | - | 870 | 100.0 | 321 | 18.3 | 531 | 74.9 |

| Donors(Respondents choosing “Yes…”) | 870 | 34.4 | - | - | - | - | 870 | 100.0 | 321 | 18.3 | 531 | 74.9 |

| Deferred Donors(Respondents choosing “No, but … I tried …”) | 130 | 5.1 | - | - | 130 | 100.0 | - | - | 113 | 6.4 | 13 | 1.8 |

| Non-Donors(Respondents choosing “No, …”) | 1526 | 60.3 | 1526 | 100.0 | - | - | - | - | 1314 | 75.0 | 165 | 23.2 |

| Do you intend to donate blood within the next 12 months? | ||||||||||||

| 1035 | 40.9 | 779 | 51.0 | 90 | 69.7 | 162 | 18.7 | 1035 | 59.1 | - | - |

| 434 | 17.1 | 339 | 22.2 | 15 | 11.9 | 79 | 9.0 | 434 | 24.8 | - | - |

| 283 | 11.2 | 196 | 12.8 | 7 | 5.3 | 80 | 9.2 | 283 | 18.3 | - | - |

| 245 | 9.7 | 110 | 7.2 | 3 | 2.2 | 132 | 15.1 | - | - | 245 | 34.6 |

| 212 | 8.4 | 45 | 2.9 | 8 | 6.4 | 158 | 18.2 | - | - | 212 | 29.9 |

| 252 | 10.0 | 10 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.1 | 241 | 27.7 | - | - | 252 | 35.5 |

| Donation Intenders(Respondents choosing “…, yes”) | 708 | 28.0 | 165 | 10.8 | 13 | 9.7 | 531 | 61.0 | - | - | 708 | 100.0 |

| Donation Non-Intenders(Respondents choosing “…, not”) | 1752 | 69.2 | 1314 | 86.1 | 113 | 86.9 | 321 | 36.9 | 1752 | 100.0 | - | - |

| Domain (D)/Main Category | Subcategory | Motives and Deterrents Previous Lifetime | Motives and Deterrents Next 12 Months | Motives and Deterrents Previous Lifetime | Motives and Deterrents Next 12 Months | Motives and Deterrents Previous Lifetime | Motives and Deterrents Next 12 Months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Females | Males | |||||||||||

| D01 Ineligibility | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 15 | 0.6 | 20 | 0.8 | 6 | 0,5 | 10 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.8 | |

| Age | 122 | 4.8 | 292 | 11.5 | 72 | 5.6 | 161 | 12.5 | 50 | 4.0 | 131 | 10.6 |

| Health | 302 | 11.9 | 346 | 13.7 | 205 | 15.9 | 227 | 17.6 | 97 | 7.8 | 119 | 9.6 | |

| Pregnancy | 6 | 0.2 | 7 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 23 | 0.9 | 15 | 0.6 | 15 | 1.2 | 11 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.3 |

| D02 Impact/Effect | Total n/domain (D01) | 454 | 17.9 | 652 | 25.8 | 295 | 2.9 | 397 | 30.8 | 159 | 12.8 | 255 | 20.5 |

| Positive | 20 | 0.8 | 16 | 0.6 | 13 | 1.0 | 10 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Negative—health | 72 | 2.8 | 67 | 2.6 | 45 | 3.5 | 37 | 2.9 | 27 | 2.2 | 30 | 2.4 | |

| Negative—risk | 37 | 1.5 | 30 | 1.2 | 21 | 1.6 | 18 | 1.4 | 16 | 1.3 | 12 | 1.0 | |

| Positive | 17 | 0.7 | 20 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.7 | 14 | 1.1 | 8 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Negative | 7 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | |

| D03 Fears/Aversion | Total n/domain (D02) | 144 | 5.7 | 133 | 5.3 | 88 | 6.8 | 78 | 6.0 | 56 | 4.5 | 55 | 4.4 |

| Fears in general | 43 | 1.7 | 42 | 1.7 | 29 | 2.2 | 25 | 1.9 | 14 | 1.1 | 17 | 1.4 |

| Fear of the needle | 90 | 3.6 | 81 | 3.2 | 65 | 5.0 | 61 | 4.7 | 25 | 2.0 | 20 | 1.6 | |

| Fear of blood | 5 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Fear to donate | 14 | 0.6 | 20 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.7 | 14 | 1.1 | 5 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.5 | |

| Fear of pain | 3 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 10 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Needles | 28 | 1.1 | 23 | 0.9 | 17 | 1.3 | 14 | 1.1 | 11 | 0.9 | 9 | 0.7 |

| Blood | 35 | 1.4 | 29 | 1.1 | 19 | 1.5 | 18 | 1.4 | 16 | 1.3 | 11 | 0.9 | |

| Other | 23 | 0.9 | 23 | 0.9 | 16 | 1.2 | 15 | 1.2 | 7 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.6 | |

| Total n/domain (D03) | 220 | 8.7 | 214 | 8.5 | 147 | 11.4 | 144 | 11.2 | 73 | 5.9 | 70 | 5.6 | |

| D04 Obstacles/Barriers | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 34 | 1.3 | 33 | 1.3 | 18 | 1.4 | 19 | 1.5 | 16 | 1.3 | 14 | 1.1 | |

| 97 | 3.8 | 28 | 1.1 | 49 | 3.8 | 12 | 0.9 | 48 | 3.9 | 16 | 1.3 | |

| 16 | 0.6 | 28 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.5 | 15 | 1.2 | 9 | 0.7 | 13 | 1.0 | |

| 143 | 5.6 | 152 | 6.0 | 80 | 6.2 | 71 | 5.5 | 63 | 5.1 | 81 | 6.5 | |

| 48 | 1.9 | 36 | 1.4 | 25 | 1.9 | 15 | 1.2 | 23 | 1.9 | 21 | 1.7 | |

| D05 Norms | Total n/domain (D04) | 304 | 12.0 | 251 | 9.9 | 162 | 12.6 | 122 | 9.5 | 142 | 11.4 | 129 | 10.4 |

| General (if no other category) | 11 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.3 |

| Future-orientated | 52 | 2.1 | 60 | 2.4 | 39 | 3.0 | 32 | 2.5 | 13 | 1.0 | 28 | 2.3 | |

| Past-orientated (self) | 13 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| 439 | 17.3 | 330 | 13.0 | 233 | 18.1 | 181 | 14.0 | 206 | 16.6 | 149 | 12.0 | |

| 113 | 4.5 | 77 | 3.0 | 59 | 4.6 | 45 | 3.5 | 54 | 4.4 | 32 | 2.6 | |

| 13 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.5 | |

| 28 | 1.1 | 20 | 0.8 | 13 | 1.0 | 7 | 0.5 | 15 | 1.2 | 13 | 1.0 | |

| 94 | 3.7 | 81 | 3.2 | 48 | 3.7 | 50 | 3.9 | 46 | 3.7 | 31 | 2.5 | |

| 30 | 1.2 | 8 | 0.3 | 23 | 1.8 | 5 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.2 | |

| 15 | 0.6 | 25 | 1.0 | 8 | 0.6 | 14 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.6 | 11 | 0.9 | |

| Total n/domain (D05) | 716 | 28.3 | 563 | 22.2 | 382 | 29.6 | 310 | 24.0 | 334 | 26.9 | 253 | 20.4 | |

| D06Image/Experience | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 69 | 2.7 | 70 | 2.8 | 44 | 3.4 | 33 | 2.6 | 25 | 2.0 | 37 | 3.0 | |

| 31 | 1.2 | 39 | 1.5 | 9 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.8 | 22 | 1.8 | 29 | 2.3 | |

| 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| 6 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.5 | |

| 15 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.4 | |

| 28 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.3 | 10 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.2 | 18 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| 56 | 2.2 | 54 | 2.1 | 28 | 2.2 | 33 | 2.6 | 28 | 2.3 | 21 | 1.7 | |

| 21 | 0.8 | 33 | 1.3 | 14 | 1.1 | 17 | 1.3 | 7 | 0.6 | 16 | 1.3 | |

| D07 Benefits/Incentives | Total n/domain (D06) | 223 | 8.8 | 220 | 8.7 | 110 | 8.5 | 104 | 8.1 | 113 | 9.1 | 116 | 9.3 |

| 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.2 | |

| 66 | 2.6 | 39 | 1.5 | 18 | 1.4 | 14 | 1.1 | 48 | 3.9 | 25 | 2.0 | |

| 14 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.0 | 11 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 21 | 0.8 | 11 | 0.4 | 13 | 1.0 | 7 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| 9 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 14 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.4 | |

| D08 Conditions | Total n/domain (D07) | 112 | 4.4 | 56 | 2.2 | 43 | 3.3 | 23 | 1.8 | 69 | 5.6 | 33 | 2.7 |

| 8 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.5 | |

| 10 | 0.4 | 18 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.5 | |

| 15 | 0.6 | 12 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.4 | |

| Total n/domain (D08) | 33 | 1.3 | 36 | 1.4 | 17 | 1.3 | 21 | 1.6 | 16 | 1.3 | 15 | 1.2 | |

| D09 Psychological Aspects | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 24 | 0.9 | 37 | 1.5 | 17 | 1.3 | 22 | 1.7 | 7 | 0.6 | 15 | 1.2 | |

| 19 | 0.8 | 20 | 0.8 | 13 | 1.0 | 12 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.6 | |

| 127 | 5.0 | 126 | 5.0 | 67 | 5.2 | 62 | 4.8 | 60 | 4.8 | 64 | 5.2 | |

| 54 | 2.1 | 40 | 1.6 | 29 | 2.2 | 16 | 1.2 | 25 | 2.0 | 24 | 1.9 | |

| 161 | 6.4 | 50 | 2.0 | 90 | 7.0 | 26 | 2.0 | 71 | 5.7 | 24 | 1.9 | |

| 45 | 1.8 | 24 | 0.9 | 26 | 2.0 | 13 | 1.0 | 19 | 1.5 | 11 | 0.9 | |

| 10 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.4 | |

| D10 Missing points of contact | Total n/domain (D09) | 432 | 17.1 | 300 | 11.9 | 243 | 18.8 | 150 | 11.6 | 189 | 15.2 | 150 | 12.1 |

| 27 | 1.1 | 16 | 0.6 | 13 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.1 | 16 | 1.3 | |

| 18 | 0.7 | 18 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.7 | |

| 28 | 1.1 | 22 | 0.9 | 17 | 1.3 | 13 | 1.0 | 11 | 0.9 | 9 | 0.7 | |

| Misc | Total n/domain (D10) | 73 | 2.9 | 54 | 2.1 | 40 | 3.1 | 22 | 1.7 | 33 | 2.7 | 32 | 2.6 |

| 26 | 1.0 | 27 | 1.1 | 17 | 1.3 | 16 | 1.2 | 9 | 0.7 | 11 | 0.9 | |

| 29 | 1.1 | 30 | 1.2 | 13 | 1.0 | 18 | 1.4 | 16 | 1.3 | 12 | 1.0 | |

| 210 | 8.3 | 304 | 12.0 | 121 | 9.4 | 172 | 13.3 | 89 | 7.2 | 132 | 10.6 | |

| Total n/domain (D11) | 265 | 10.5 | 361 | 14.3 | 151 | 11.7 | 206 | 16.0 | 114 | 9.2 | 155 | 12.5 | |

| Domain (D)/Main Category | Subcategory | Non-Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Deferred Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Non-Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Deferred Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Donors (Previous Lifetime) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | ||||||||||||

| D01 Ineligibility | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 5 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.1 | 2 | 4.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Age | 67 | 7.8 | 2 | 2.4 | 3 | 0.7 | 43 | 6.7 | 3 | 6.1 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Health | 143 | 16.6 | 46 | 54.8 | 15 | 3.3 | 64 | 10.0 | 29 | 59.2 | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Pregnancy | 6 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 9 | 1.0 | 5 | 6.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 6.1 | 2 | 0.5 |

| D02 Impact/Effect | Total n/domain (D01) | 222 | 25.8 | 54 | 64.3 | 18 | 4.0 | 114 | 17.8 | 36 | 73.5 | 9 | 2.0 |

| Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 12 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.6 |

| Negative—health | 42 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 25 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Negative—risk | 20 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 16 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Positive | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.8 |

| Negative | 5 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D03 Fears/Aversion | Total n/domain (D02) | 64 | 7.4 | 1 | 1.2 | 23 | 5.1 | 41 | 6.4 | 1 | 2.0 | 14 | 3.2 |

| Fears in general | 29 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fear of the needle | 65 | 7.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear of blood | 4 | 0..5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear to donate | 9 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear of pain | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Needles | 17 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Blood | 19 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 16 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total n/domain (D03) | 146 | 17.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 73 | 11.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D04 Obstacles/Barriers | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 17 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 49 | 5.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 45 | 7.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| 6 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 76 | 8.8 | 2 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.4 | 61 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| 23 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 23 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D05 Norms | Total n/domain (D04) | 155 | 18.0 | 3 | 3.6 | 3 | 0.7 | 137 | 21.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.1 |

| General (if no other category) | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 2.0 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Future-orientated | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 3.6 | 35 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 3.6 | |

| Past-orientated (self) | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1.2 | 7 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| 11 | 1.3 | 15 | 17.9 | 207 | 45.8 | 5 | 0.8 | 3 | 6.1 | 198 | 44.9 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 61 | 13.5 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 48 | 10.9 | |

| 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 9 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 13 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 3.2 | |

| 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 2.4 | 42 | 9.3 | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.0 | 42 | 9.5 | |

| 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1.2 | 21 | 4.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.6 | |

| 8 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total n/domain (D05) | 29 | 3.4 | 20 | 23.8 | 333 | 73.7 | 28 | 4.4 | 6 | 12.2 | 300 | 68.0 | |

| D06Image/Experience | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 3.6 | 39 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 5.7 | |

| 9 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 6 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.4 | 8 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 4.1 | |

| 8 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 4.4 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 5.7 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 1.2 | 11 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.4 | |

| D07 Benefit/Incentives | Total n/domain (D06) | 22 | 2.6 | 7 | 8.3 | 81 | 17.9 | 30 | 4.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 83 | 18.8 |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 17 | 3.8 | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.0 | 44 | 10.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.6 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 2.0 | |

| D08 Conditions | Total n/domain (D07) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 42 | 9.3 | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.0 | 65 | 14.7 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Total n/domain (D08) | 9 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.5 | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 2.0 | |

| D09 Psychological Aspects | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 16 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 13 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.8 | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 67 | 7.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 59 | 9.2 | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 29 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 90 | 10.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 71 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 4.3 | |

| 5 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0. | 5 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D10 Missing points of contact | Total n/domain (D09) | 219 | 25.5 | 1 | 1.2 | 23 | 5.1 | 167 | 26.1 | 2 | 4.1 | 20 | 4.5 |

| 12 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 14 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 10 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 15 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Misc | Total n/domain (D10) | 37 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 30 | 4.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 |

| 10 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.4 | |

| 9 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.9 | 15 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 95 | 11.0 | 10 | 11.9 | 14 | 3.1 | 67 | 10.5 | 6 | 12.2 | 15 | 3.4 | |

| Total n/domain (D11) | 114 | 13.3 | 11 | 13.1 | 23 | 5.1 | 85 | 13.3 | 6 | 12.2 | 22 | 5.0 | |

| Domain (D)/Main Category | Subcategory | Non-Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Non-Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Intenders (Next 12 Months) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | ||||||||

| D01 Ineligibility | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 10 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Age | 157 | 16.1 | 2 | 0.5 | 127 | 17.0 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Health | 220 | 22.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 117 | 15.7 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Pregnancy | 7 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 10 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| D02 Impact/Effect | Total n/domain (D01) | 385 | 39.4 | 5 | 1.4 | 249 | 33.4 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Positive | 2 | 0.2 | 7 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.4 |

| Negative—health | 34 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 28 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Negative—risk | 17 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.7 |

| Negative | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D03 Fears/Aversion | Total n/domain (D02) | 54 | 5.5 | 19 | 5.4 | 41 | 5.5 | 12 | 3.4 |

| Fears in general | 24 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fear of the needle | 60 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear of blood | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear to donate | 14 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fear of pain | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 8 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Needles | 12 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Blood | 17 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 14 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Total n/domain (D03) | 138 | 14.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 67 | 9.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| D04 Obstacles/Barriers | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 17 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.5 | 10 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.8 | |

| 11 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.9 | 9 | 2.5 | |

| 14 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 60 | 6.1 | 9 | 2.4 | 68 | 9.1 | 11 | 3.1 | |

| 14 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 19 | 2.6 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| D05 Norms | Total n/domain (D04) | 106 | 10.8 | 13 | 3.7 | 103 | 13.8 | 23 | 6.5 |

| General (if no other category) | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Future-orientated | 3 | 0.3 | 28 | 7.3 | 5 | 0.7 | 23 | 6.5 | |

| Past-orientated (self) | 1 | 0.1 | 6 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 14 | 1.4 | 162 | 42.4 | 10 | 1.3 | 135 | 38.2 | |

| 6 | 0.6 | 39 | 10.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 30 | 8.5 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.8 | 4 | 0.5 | 9 | 2.5 | |

| 1 | 0.1 | 49 | 12.8 | 2 | 0.3 | 28 | 7.9 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.8 | |

| 14 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total n/domain (D05) | 41 | 4.2 | 264 | 74.8 | 36 | 4.8 | 210 | 59.5 | |

| D06Image/Experience | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 31 | 8.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 37 | 10.5 | |

| 6 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.5 | 28 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 6 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.4 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 13 | 1.3 | 20 | 5.2 | 3 | 0.4 | 18 | 5.1 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 17 | 4.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 13 | 3.7 | |

| D07 Benefits/Incentives | Total n/domain (D06) | 27 | 2.8 | 75 | 21.2 | 41 | 5.5 | 74 | 21.0 |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 8 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.6 | 11 | 1.5 | 13 | 3.7 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| D08 Conditions | Total n/domain (D07) | 8 | 0.8 | 15 | 4.2 | 14 | 1.9 | 18 | 5.1 |

| 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| 8 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| 5 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Total n/domain (D08) | 14 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.4 | 8 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.7 | |

| D09 Psychological Aspects | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 5 | 0.5 | 17 | 4.5 | 2 | 0.3 | 12 | 3.4 | |

| 11 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 56 | 5.7 | 3 | 0.8 | 61 | 8.2 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 15 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 21 | 2.8 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| 20 | 2.0 | 4 | 1.0 | 22 | 3.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 4 | 0.4 | 8 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 10 | 2.8 | |

| 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| D10 Missing points of contact | Total n/domain (D09) | 112 | 11.5 | 32 | 9.1 | 117 | 15.7 | 27 | 7.6 |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.5 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| 9 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 12 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Misc | Total n/domain (D10) | 21 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 23 | 3.1 | 7 | 2.0 |

| 11 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.0 | 5 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.4 | |

| 15 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 11 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 148 | 15.1 | 16 | 4.2 | 93 | 12.5 | 32 | 9.1 | |

| Total n/domain (D11) | 174 | 17.8 | 22 | 6.2 | 109 | 14.6 | 38 | 10.8 | |

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Blood Safety and Availability Age and Gender of Blood Donors. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blood-safety-and-availability (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Seifried, E.; Klueter, H.; Weidmann, C.; Staudenmaier, T.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Henschler, R.; Greinacher, A.; Mueller, M.M. How much blood is needed? Vox Sang. 2011, 100, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greinacher, A.; Weitmann, K.; Lebsa, A.; Alpen, U.; Gloger, D.; Stangenberg, W.; Kiefel, V.; Hoffmann, W. A population-based longitudinal study on the implications of demographics on future blood supply. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2986–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönborn, L.; Weitmann, K.; Greinacher, A.; Hoffmann, W. Characteristics of recipients of red blood cell concentrates in a german federal state. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2020, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meybohm, P.; Schmitz-Rixen, T.; Steinbicker, A.; Schwenk, W.; Zacharowski, K. Das patient-blood-management-konzept: Gemeinsame empfehlung der deutschen gesellschaft für anästhesiologie und intensivmedizin und der deutschen gesellschaft für chirurgie. Chirurg 2017, 88, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Goldman, M.; Engelfriet, C.P.; Reesink, H.W.; Hetherington, C.; Hall, S.; Steed, A.; Harding, S.; Westman, P.; Gogarty, G.; et al. Donor recruitment research. Vox Sang. 2007, 93, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerzteblatt Nur Zwei Bis Drei Prozent Der Menschen in Deutschland Spenden Blut. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/95832/Nur-zwei-bis-drei-Prozent-der-Menschen-in-Deutschland-spenden-Blut (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Masser, B.; France, C.R.; Himawan, L.K.; Hyde, M.K.; Smith, G. The impact of the context and recruitment materials on nondonors’ willingness to donate blood. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2995–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masser, B.; Ferguson, E.; Merz, E.-M.; Williams, L. Beyond description: The predictive role of affect, memory, and context in the decision to donate or not donate blood. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2020, 47, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffin, K.; Muehlan, H.; Sümnig, A.; Schmidt, S.; Greinacher, A. Psychologische optionen zur reaktivierung und bindung von blutspendern. Transfus. Immunhämatol. Hämother. Immungen. Zellther. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagot, K.L.; Murray, A.L.; Masser, B.M. How can we improve retention of the first-time donor? A systematic review of the current evidence. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2016, 30, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavić, N.; Pagliariccio, A.; Bulajić, M.; Marinozzi, M.; Miletić, G.; Vlatković, A. Blood donor satisfaction and the weak link in the chain of donation process. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.; Walsh, R.J. A survey of some voluntary blood donors in new South Wales. Med. J. Aust. 1956, 43, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednall, T.C.; Bove, L.L. Donating blood: A meta-analytic review of self-reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2011, 25, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucoloto, M.L.; Gonçalez, T.; Menezes, N.P.; McFarland, W.; Custer, B.; Martinez, E.Z. Fear of blood, injections and fainting as barriers to blood donation in Brazil. Vox Sang. 2019, 114, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojka, B.N.; Sojka, P. The blood donation experience: Self-reported motives and obstacles for donating blood. Vox Sang. 2008, 94, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersma, T.W.; Bekkers, R.; de Kort, W.; Merz, E.M. Blood donation across the life course: The influence of life events on donor lapse. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E.; Atsma, F.; De Kort, W.; Veldhuizen, I. Exploring the pattern of blood donor beliefs in first-time, novice, and experienced donors: Differentiating reluctant altruism, pure altruism, impure altruism, and warm glow. Transfusion 2012, 52, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhuizen, I.; Ferguson, E.; De Kort, W.; Donders, R.; Atsma, F. Exploring the dynamics of the theory of planned behavior in the context of blood donation: Does donation experience make a difference? Transfusion 2011, 51, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huis In ‘t Veld, E.M.J.; de Kort, W.L.A.M.; Merz, E.M. Determinants of blood donation willingness in the European Union: A cross-country perspective on perceived transfusion safety, concerns, and incentives. Transfusion 2019, 59, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinghaus, E.P.; Milkovich, M.B. Donors and nondonors: Communication and information. Transfusion 1975, 15, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboz, P.; Cunéo, B. How barriers to blood donation differ between lapsed donors and non-donors in France. Transfus. Med. 2010, 20, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Sheeran, P.; Conner, M.; Germain, M.; Blondeau, D.; Gagné, C.; Beaulieu, D.; Naccache, H. Factors explaining the intention to give blood among the general population. Vox Sang. 2005, 89, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Prävalenz Der Blutspende. Available online: https://www.bzga.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/2018-06-08-neue-bzga-umfrage-zeigt-fast-jeder-zweite-hat-schon-einmal-blut-gespendet/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Harrington, M.; Sweeney, M.R.; Bailie, K.; Morris, K.; Kennedy, A.; Boilson, A.; O’Riordan, J.; Staines, A.A. What would encourage blood donation in Ireland? Vox Sang. 2007, 92, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiddi, P.; Alfieri, S.; Marta, E.; Saturni, V. New donors, loyal donors, and regular donors: Which motivations sustain blood donation? Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2015, 52, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, W.R.; High, P.M.; Schreiber, G.B. AIDS knowledge and beliefs related to blood donation in US adults: Results from a National Telephone Survey. Transfusion 2012, 52, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, C.; Schneider, S.; Weck, E.; Menzel, D.; Klüter, H.; Müller-Steinhardt, M. Monetary compensation and blood donor return: Results of a donor survey in Southwest Germany. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2014, 41, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niza, C.; Tung, B.; Marteau, T.M. Incentivizing blood donation: Systematic review and meta-analysis to test Titmuss’ hypotheses. Heal. Psychol. 2013, 32, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacetera, N.; Macis, M. Do all material incentives for pro-social activities backfire? The response to cash and non-cash incentives for blood donations. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, T.Z.; Hersey, D.P.; Cone, D.C.; Agrawal, P. Tapping into a vital resource: Understanding the motivators and barriers to blood donation in Sub-Saharan Africa Puiser dans une ressource vitale: Comprendre les motivations et les obstacles au don de sang. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 6, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S.; Hinz, A.; Schwarz, R. Einstellung zur blutspende in Deutschland–Ergebnisse einer reprasentativen untersuchung. Infusionsther. Transfusionsmed. 2000, 27, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gemelli, C.N.; Thijsen, A.; van Dyke, N.; Masser, B.M.; Davison, T.E. Emotions experienced when receiving a temporary deferral: Perspectives from staff and donors. ISBT Sci. Ser. 2018, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliassen, H.S.; Hervig, T.; Backlund, S.; Sivertsen, J.; Iversen, V.V.; Kristoffersen, M.; Wengaard, E.; Gramstad, A.; Fosse, T.; Bjerkvig, C.K.; et al. Immediate effects of blood donation on physical and cognitive performance—A randomized controlled double-blinded trial. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E.; Taylor, M.; Keatley, D.; Flynn, N.; Lawrence, C. Blood donors’ helping behavior is driven by warm glow: More evidence for the blood donor benevolence hypothesis. Transfusion 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangerup, I.; Kramp, N.L.; Ziegler, A.K.; Dela, F.; Magnussen, K.; Helge, J.W. Temporary impact of blood donation on physical performance and hematologic variables in women. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, A.; Picker, S.M.; Schneider, A.; Lefering, R.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.; Gathof, B.S. Effect of blood donation on well-being of blood donors. Transfus. Med. 2008, 18, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, P.; Sümnig, A.; Esefeld, M.; Greffin, K.; Kaderali, L.; Greinacher, A. Well-being and return rate of first-time whole blood donors. Vox Sang. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffin, K.; Muehlan, H.; Tomczyk, S.; Suemnig, A.; Schmidt, S.; Greinacher, A. In the mood for a blood donation? Pilot study about momentary mood, satisfaction, and return behavior in deferred first-time donors. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalsky, J.M.; France, C.R.; France, J.L.; Whitehouse, E.A.; Himawan, L.K. Blood donation fears inventory: Development and validation of a measure of fear specific to the blood donation setting. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2014, 51, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersma, T.W.; Bekkers, R.; de Kort, W.; Merz, E.-M. Altruism in blood donation: Out of sight out of mind? Closing donation centers influences blood donor lapse. Health Place 2021, 67, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Font, J.; Jofre-Bonet, M.; Yen, S.T. Not all incentives wash out the warm glow: The case of blood donation revisited. Kyklos 2013, 66, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, L.; Stutzer, A.; Yavuzcan, G.; Frey, B.M. Free cholesterol testing as a motivation device in blood donations: Evidence from field experiments. Transfusion 2009, 49, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, T.E.; Masser, B.M.; Gemelli, C.N. Deferred and edterred: A review of literature on the impact of deferrals on blood donors. ISBT Sci. Ser. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalez, T.T.; Sabino, E.C.; Schlumpf, K.S.; Wright, D.J.; Mendrone, A.; Lopes, M.; Leão, S.; Miranda, C.; Capuani, L.; Carneiro-Proietti, A.B.F.; et al. Analysis of donor deferral at three blood centers in Brazil. Transfusion 2013, 53, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoma, A.M.; Goto, A.; Sawamura, Y.; Nollet, K.E.; Ohto, H.; Yasumura, S. Analysis of blood donor deferral in Japan: Characteristics and reasons. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2013, 49, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shaer, L.; Sharma, R.; Abdulrahman, M. Analysis of blood donor pre-donation deferral in Dubai: Characteristics and reasons. J. Blood Med. 2017, 8, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spekman, M.L.C.; van Tilburg, T.G.; Merz, E.-M. Do deferred donors continue their donations? A large-scale register study on whole blood donor return in The Netherlands. Transfusion 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total *** | Non- Donors | Deferred Donors | Donors | Donation Non-Intenders | Donation- Intenders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| 1241 | 49.0 | 716 | 46.9 | 50 | 38.7 | 474 | 54.5 | 825 | 47.1 | 382 | 53.9 |

| 1290 | 51.0 | 810 | 53.1 | 79 | 61.3 | 396 | 45.5 | 927 | 52.9 | 326 | 46.1 |

| Age Group | ||||||||||||

| 95 | 3.8 | 86 | 35.6 | 3 | 2.0 | 7 | 0.8 | 26 | 4.3 | 19 | 2.7 |

| 249 | 9.8 | 178 | 11.7 | 8 | 6.2 | 62 | 7.1 | 127 | 7.2 | 112 | 15.9 |

| 356 | 14.0 | 212 | 13.9 | 21 | 16.0 | 121 | 13.9 | 217 | 12.4 | 131 | 18.5 |

| 357 | 14.1 | 202 | 13.2 | 20 | 15.2 | 135 | 15.5 | 223 | 12.7 | 118 | 16.7 |

| 458 | 18.1 | 251 | 16.4 | 24 | 18.2 | 183 | 21.2 | 282 | 16.1 | 164 | 23.2 |

| 398 | 15.7 | 231 | 15.1 | 22 | 16.6 | 146 | 16.7 | 290 | 16.5 | 98 | 13.8 |

| 362 | 14.3 | 208 | 13.6 | 24 | 18.5 | 131 | 15.0 | 308 | 17.6 | 47 | 6.7 |

| 223 | 8.8 | 139 | 9.1 | 9 | 6.6 | 75 | 8.7 | 202 | 11.5 | 16 | 2.3 |

| 33 | 1.3 | 20 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.1 | 29 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Nationality ** | ||||||||||||

| 2425 | 95.8 | 1435 | 94.1 | 127 | 98.0 | 859 | 98.8 | 1671 | 95.4 | 693 | 97.8 |

| 106 | 4.2 | 91 | 5.9 | 3 | 2.0 | 11 | 1.2 | 80 | 4.6 | 15 | 2.2 |

| Confession | ||||||||||||

| 940 | 37.1 | 582 | 38.1 | 44 | 33.6 | 314 | 36.1 | 653 | 37.3 | 262 | 36.9 |

| 788 | 31.1 | 473 | 31.0 | 43 | 33.0 | 268 | 30.8 | 549 | 31.3 | 222 | 31.4 |

| 67 | 2.6 | 59 | 3.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.6 | 48 | 2.8 | 10 | 1.4 |

| 53 | 2.1 | 28 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.9 | 20 | 2.3 | 32 | 1.8 | 21 | 2.9 |

| 584 | 23.1 | 323 | 21.2 | 32 | 24.4 | 228 | 26.2 | 399 | 22.8 | 168 | 23.8 |

| Family Status | ||||||||||||

| 1194 | 47.2 | 681 | 44.7 | 66 | 51.3 | 445 | 51.2 | 857 | 48.9 | 305 | 43.0 |

| 30 | 1.2 | 18 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.8 | 8 | 0.9 | 20 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.1 |

| 319 | 12.6 | 181 | 11.8 | 21 | 16.5 | 117 | 13.4 | 197 | 11.3 | 113 | 15.9 |

| 591 | 23.4 | 388 | 25.4 | 20 | 15.5 | 176 | 20.2 | 360 | 20.6 | 214 | 30.2 |

| 194 | 7.7 | 126 | 8.3 | 3 | 2.3 | 62 | 7.1 | 134 | 7.7 | 54 | 7.6 |

| 196 | 7.7 | 122 | 8.0 | 14 | 10.9 | 55 | 6.3 | 177 | 10.1 | 14 | 2.0 |

| Education (Qualification) | ||||||||||||

| 53 | 2.1 | 43 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.1 | 8 | 0.9 | 41 | 2.4 | 7 | 1.0 |

| 767 | 30.3 | 492 | 32.2 | 36 | 27.5 | 237 | 27.2 | 618 | 35.3 | 134 | 18.9 |

| 977 | 38.6 | 555 | 36.3 | 51 | 39.3 | 370 | 42.6 | 619 | 35.4 | 328 | 46.2 |

| 404 | 15.9 | 231 | 15.1 | 18 | 14.4 | 153 | 17.6 | 242 | 13.8 | 148 | 20.9 |

| 223 | 8.8 | 114 | 7.4 | 19 | 15.0 | 90 | 10.4 | 146 | 8.3 | 70 | 9.9 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | - | - | 3 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.3 | - | - |

| 93 | 3.7 | 87 | 5.7 | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.4 | 74 | 4.2 | 18 | 2.6 |

| Income (Household) | ||||||||||||

| 496 | 19.6 | 323 | 21.1 | 23 | 17.5 | 149 | 17.1 | 373 | 21.3 | 102 | 14.3 |

| 768 | 30.3 | 447 | 29.3 | 37 | 28.2 | 282 | 32.4 | 554 | 31.6 | 199 | 28.0 |

| 599 | 23.7 | 355 | 23.3 | 34 | 26.6 | 209 | 24.0 | 403 | 23.0 | 181 | 25.5 |

| 565 | 22.3 | 329 | 21.6 | 29 | 22.1 | 207 | 23.8 | 348 | 19.9 | 202 | 28.5 |

| (a) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Deferred Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Effect Size (Sig.) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Cramer’s V (p-Value) | ||

| Total | 1526 | 60.4 | 130 | 5.1 | 870 | 34.4 | ||

| Sex | 0.086 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 716 | 46.9 | 50 | 38.7 | 474 | 54.5 | ||

| 810 | 53.1 | 79 | 61.3 | 396 | 45.5 | ||

| Age Group | 0.111 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 86 | 5.6 | 3 | 2.0 | 7 | 0.8 | ||

| 178 | 11.7 | 8 | 6.2 | 62 | 7.1 | ||

| 212 | 13.9 | 21 | 16.0 | 121 | 13.9 | ||

| 202 | 13.2 | 20 | 15.2 | 135 | 15.5 | ||

| 251 | 16.4 | 24 | 18.2 | 183 | 21.1 | ||

| 231 | 15.1 | 22 | 16.6 | 146 | 16.7 | ||

| 208 | 13.6 | 24 | 18.5 | 131 | 15.0 | ||

| 139 | 9.1 | 9 | 6.6 | 75 | 8.7 | ||

| 20 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.1 | ||

| Confession | 0.084 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 582 | 38.1 | 44 | 33.6 | 314 | 36.1 | ||

| 473 | 31.0 | 43 | 33.0 | 268 | 30.8 | ||

| 59 | 3.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.6 | ||

| 28 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.9 | 20 | 2.3 | ||

| 323 | 21.2 | 32 | 24.4 | 228 | 26.2 | ||

| Family Status | 0.069 | 0.020 | ||||||

| 681 | 44.7 | 66 | 51.3 | 445 | 51.2 | ||

| 39 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.1 | 16 | 1.8 | ||

| 112 | 7.4 | 15 | 11.7 | 73 | 8.4 | ||

| 388 | 25.4 | 20 | 15.1 | 176 | 20.2 | ||

| 160 | 10.5 | 10 | 7.7 | 90 | 10.4 | ||

| 136 | 8.9 | 14 | 11.1 | 65 | 7.4 | ||

| Education (Qualification) | 0.127 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 43 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.1 | 8 | 0.9 | ||

| 492 | 32.2 | 36 | 27.5 | 237 | 27.2 | ||

| 553 | 36.3 | 51 | 39.3 | 370 | 42.6 | ||

| 231 | 15.1 | 19 | 14.4 | 153 | 17.6 | ||

| 114 | 7.4 | 19 | 15.0 | 90 | 10.4 | ||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | ||

| 87 | 5.7 | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.4 | ||

| Income (Household) | 0.054 | 0.021 | ||||||

| 323 | 21.1 | 23 | 17.5 | 149 | 17.1 | ||

| 802 | 52.6 | 71 | 54.8 | 491 | 56.5 | ||

| 329 | 21.6 | 29 | 22.1 | 207 | 23.8 | ||

| (b) | ||||||||

| Non-Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Effect Size (Sig.) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | Cramer’s V (p-Value) | ||||

| Total | 1752 | 71.2 | 708 | 28.8 | ||||

| Sex | 0.062 | 0.002 | ||||||

| 825 | 47.1 | 382 | 53.9 | ||||

| 927 | 52.9 | 326 | 46.1 | ||||

| Age Group | 0.268 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 75 | 4.3 | 19 | 2.7 | ||||

| 127 | 7.2 | 112 | 15.9 | ||||

| 217 | 12.4 | 131 | 18.5 | ||||

| 223 | 12.7 | 118 | 16.7 | ||||

| 282 | 16.1 | 164 | 23.2 | ||||

| 290 | 16.5 | 98 | 13.8 | ||||

| 308 | 17.6 | 47 | 6.7 | ||||

| 202 | 11.5 | 16 | 2.3 | ||||

| 29 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.2 | ||||

| Confession | 0.055 | 0.195 | ||||||

| 653 | 37.3 | 262 | 36.9 | ||||

| 549 | 31.3 | 222 | 31.4 | ||||

| 48 | 2.8 | 10 | 1.4 | ||||

| 32 | 1.8 | 21 | 2.9 | ||||

| 399 | 22.8 | 168 | 23.8 | ||||

| Family Status | 0.183 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 857 | 48.9 | 305 | 43.0 | ||||

| 42 | 2.4 | 13 | 1.8 | ||||

| 114 | 6.5 | 82 | 11.5 | ||||

| 357 | 20.4 | 210 | 29.6 | ||||

| 176 | 10.0 | 78 | 11.1 | ||||

| 193 | 11.0 | 19 | 2.6 | ||||

| (Qualification) | 0.189 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 41 | 2.4 | 7 | 1.0 | ||||

| 618 | 35.3 | 134 | 18.9 | ||||

| 619 | 35.3 | 328 | 46.2 | ||||

| 242 | 13.8 | 148 | 20.9 | ||||

| 146 | 8.3 | 70 | 9.9 | ||||

| 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| 74 | 4.2 | 18 | 2.6 | ||||

| Income (Household) | 0.110 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 373 | 21.3 | 102 | 14.3 | ||||

| 957 | 54.6 | 379 | 53.5 | ||||

| 348 | 19.9 | 202 | 28.5 | ||||

| Main Categories | Subcategories | Definition | Anchor Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ineligibility | All statements relating to reasons for a missing/inadequate “suitability” for blood donation (e.g., existing diseases) | ||

| Unspecific reason | Lack of “eligibility” without giving specific reasons. | “I am not suitable.” | |

| Specific reason | Age | Lack of “eligibility” because individual is too young or old to donate blood. | “Due to age.” |

| Health | Lack of “eligibility” due to health restrictions (e.g., illness). | “Not allowed because of illness.” | |

| Pregnancy | Temporary lack of “eligibility” due to pregnancy. | “I am pregnant.” | |

| Specific reason | other | Statements of other specific reasons. | “Trips abroad” |

| Impact and Effect | Statements concerning the anticipated impact/effect | ||

| Physical consequences | Positive | Due to the expected positive physical effects for the donor (e.g., vitality). | “I’m doing something good for myself, my body.” |

| Negative—health | Due to the expected negative physical effects for the donor (e.g., cardiovascular system problems). | “My cardiovascular system can’t really handle it” | |

| Negative—risk | Due to the expected health risks for the donor (e.g., infection). | “Because of the risk of infection.” | |

| Mental/psychological well-being | Positive | Due to the expected positive psychological effects for the donor (e.g., wellbeing). | “It’s good for me.” |

| Negative | Due to the expected negative psychological effects for the donor (e.g., feeling unwell). | “It’s not good for me” | |

| Fears and Aversion | All statements relating to possible aversions and fears regarding blood donation. | ||

| Fears | Fears in general | All statements relating to fear in general, without further specification. | “Am afraid.” |

| Fear of the needle | Due to existing/anticipated fear of needles. | “Fear of needles.” | |

| Fear of blood | Due to existing/anticipated fear of blood. | “Am afraid of blood.” | |

| Fear to donate | Due to existing/anticipated fear to donate. | “Am afraid of blood getting taken.” | |

| Fear of pain | Due to the existing/anticipated fear of pain. | “Fear of pain.” | |

| other | Statements relating to specific other fears. | “Fear of doctors.” | |

| Aversion | Needles | Due to a personal aversion to needles. | “Have an aversion to needles and syringes.” |

| Blood | Due to a personal aversion to blood. | “Can’t see blood.” | |

| other | Statements relating to other specific aversions. | “I dislike it.” | |

| Obstacles and Barriers | All statements relating to possible logistical/organizational obstacles. | ||

| Lack of information | Due to a lack of information and knowledge about blood donation. | “I wouldn’t even know where and how I could donate.” | |

| No opportunity/Lack of possibilities | Due to a lack of opportunities/possibilities (e.g., distance to blood donation) | “No opportunity nearby.” | |

| Organization/effort | Due to the organizational effort involved. | “Too cumbersome, complicated.” | |

| Time/Lack of time | Due to a lack of time. | “I hardly have time for that.” | |

| Personal reasons | Due to personal reasons regarding logistics/organization but that do not fall under the categories named above. | “Can’t set it up.” | |

| Norms | All statements relating to normative reasons/motives. | ||

| Reciprocity | General (if none of the three subcategories) | Due to the recognition of the norm of reciprocity because of past or potential future utilization. | “Blood for blood.” |

| Future-orientated | Due to the expectation of increasing the future possibility to receive someone else’s blood by donating blood now. | “A situation could come up in which one needs blood.” | |

| Past-orientated (self) | Due to the recognition of the norm of reciprocity because of having received someone else’s blood in the past. | “To give back something of what I have received.” | |

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | Due to the recognition of the norm of reciprocity because friends/family having received someone else’s blood in the past. | “In return for the blood my child received.” | |

| Altruism | Due to the unconditional necessity of helping people (in need) and saving lives. | “That is a way in which I can save lives.” | |

| (Feeling of) Obligation/self-evident/social conscientiousness and responsibility | Generally described subjective obligation of the social norm/expectation to donate blood. | “To do something for the community.” | |

| Religious reasons | Due to religious/denominational reasons. | “For religious reasons.” | |

| Personal belief | Due to personal beliefs, if not described through another normative belief. | “It is important for me personally.” | |

| Important/necessary/meaningful/good cause | Generally described relevance to donate blood. | “Because it is important.” | |

| Vocational affiliation | Due to one’s own vocation (e.g., working in the health care system). | “Through my work in the clinic.” | |

| Main categories | Subcategories | Definition | Anchor example |

| Surrendering responsibility | Due to the non-existent insight into why individuals should become active/Personal need of one’s blood. | “Enough others do it.”/“I need my blood myself.” | |

| Image and Experience | All motives that relate to a specific characteristic of blood donation. | ||

| Compensate for the lack of blood products/Support the health care system | Due to the knowledge of the lack of blood conserves and the necessity of blood donation for a functioning health care system | “Demand is constantly rising.” | |

| Lack of trust (rip-off/crime/fraud/profiteering—media reports) | Due to a lack of trust in the blood donation system, amongst others formulated in the form of general charges | “Because I don’t want to support such profiteering.” | |

| Try it out (curiosity motive) | Curiosity | “I was curious.” | |

| No need present | Due to a lack of need | “There is no lack of blood.” | |

| Rare blood type | Due to the knowledge of the rarity (and thus the relevance of the donation) of the own blood type | “Important, I have a rare blood type.” | |

| Advertisement/Campaign/Phone call/Appeal | Donated due to campaigns or advertisements | “Promo day.” | |

| (Missing) previous experience or habit | Due to already collected experience in donating | “I am a permanent donor and regularly donate blood.” | |

| Absence of disadvantages | Due to the absence of obstacles/disadvantages | “Nothing bad” “it doesn’t hurt me” | |

| Benefits and Incentives | All motives mentioning compensatory measures. | ||

| Blood donor card | Receive a blood donor card | “Interested in a blood-type card.” | |

| Compensation | Financial compensation | “Money!” | |

| Determination of the blood type | Determination of the blood type free of charge | “That way I could learn my blood type.” | |

| Health check/screening | Health check/screening free of charge | “At the same time one gets a health check.” | |

| Exemption from work/school | Exemption from work/school to donate blood | “I wanted a little time off work.” | |

| Other services | Due to services/discounts that the donor receives | “Extra holiday” “…and there was pea soup” | |

| Conditions | Statements of specific conditions in which blood donations would be given. | ||

| For personal need only | For personal treatment/prevention only | “For myself alone.” | |

| Only for family/important others/if person is known | Blood donation for close relatives or acquaintances/trusted persons only | “Why should I? If, then only for relatives.” | |

| In case of a disaster/emergency/personal experience | Due to special demand or circumstance | “Car crash of my parents” “Train accident” | |

| Psychological Aspects | Statements related to aspects of attitude, volition, and behaviour. | ||

| Will be made up for/is planned | Due to the fact that the respondent has not donated blood despite existing intention, but plans to make up for this | “I want to do it soon.” | |

| Not ready yet | Due to the fact that the respondent doesn’t feel ready to donate blood | “I’m not ready for it yet.” | |

| No interest/no will | Due to the fact that the respondent is unwilling and uninterested to donate blood. | “It doesn’t interest me.” | |

| Indifference/passivity/negligence/comfort/no desire | Due to the fact that the respondent is indifferent/passive concerning blood donation or negligent/desireless or too comfortable to donate | “I don’t desire to do it.” | |

| Not thought about it | Due to the fact that the respondent has not thought about it yet | “Haven’t thought about it yet.” | |

| Social aspect/peer group movement/personal influence and advice | Due to social motivation | “My ex-girlfriend took me there.” | |

| Refusal to donate blood | Due to the belief that blood donation isn’t important/meaningless or is refused | “Meaningless” | |

| Missing points of contact | Statements related to missing triggers/contact points. | ||

| No request/appellation/call | Due to the fact that the respondent has not explicitly been asked/called upon to do so or been addressed separately | “Someone should ask me about it once.” | |

| Missing reason/occasion | Due to the fact that there has not been a special occasion or specific reason to do so | “There hasn’t been an occasion to do it yet.” | |

| For no reason | Lack of awareness of the motivations and obstacles | “No reason.” | |

| Misc | Other statements | ||

| Other | Due to aspects that cannot be assigned to the other categories | (various) | |

| Do not know | Respondent doesn’t know/cannot remember anymore | “Don’t know.” | |

| Not specified | Statement is missing or was actively refused | “None.” | |

| (a) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain (D)/Main Category | Subcategory | Non-Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Deferred Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Donors (Previous Lifetime) | Effect Size (Sig.) | |||

| D01 Ineligibility | n | % | n | % | n | % | Cramer’s V (p-Value) | |

| Unspecific reason | 12 | 0.8 | 3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.071 (0.002) | |

| Age | 110 | 7.3 | 5 | 3.8 | 7 | 0.8 | 0.144 (0.000) |

| Health | 207 | 13.8 | 75 | 56.4 | 19 | 2.1 | 0.365 (0.000) | |

| Pregnancy | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.040 (0.128) | |

| Other | 12 | 0.8 | 8 | 6.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.129 (0.000) |

| D02 Impact/Effect | Total n/domain (D01) | 336 | 22.4 | 90 | 67.7 | 27 | 3.0 | 0.387 (0.000) |

| Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 19 | 2.1 | 0.113 (0.000) |

| Negative—health | 67 | 4.5 | 1 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.118 (0.000) | |

| Negative—risk | 36 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.094 (0.000) | |

| Positive | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.8 | 0.101 (0.000) |

| Negative | 7 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.044 (0.091) | |

| D03 Fears/Aversion | Total n/domain (D02) | 105 | 7.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 37 | 4.1 | 0.072 (0.001) |

| Fears in general | 43 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.109 (0.000) |

| Fear of the needle | 90 | 6.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.159 (0.000) | |

| Fear of blood | 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.037 (0.180) | |

| Fear to donate | 14 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.062 (0.008) | |

| Fear of pain | 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.029 (0.358) | |

| Other | 9 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.047 (0.062) | |

| Needles | 28 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.088 (0.000) |

| Blood | 35 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.098 (0.000) | |

| Other | 23 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.079 (0.000) | |

| D04 Obstacles/Barriers | Total n/domain (D03) | 219 | 14.6 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.253 (0.000) |

| Lack of information | 32 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.084 (0.000) | |

| No opportunity/Lack of possibilities | 94 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.153 (0.000) | |

| Organization/effort | 15 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.059 (0.011) | |

| Time/Lack of time | 137 | 9.1 | 2 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.182 (0.000) | |

| Personal reasons | 46 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.108 (0.000) | |

| D05 Norms | Total n/domain (D04) | 292 | 19.5 | 3 | 2.3 | 8 | 0.9 | 0.278 (0.000) |

| General (if no other category) | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.7 | 0.054 (0.026) |

| Future-orientated | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 2.3 | 51 | 5.7 | 0.182 (0.000) | |

| Past-orientated (self) | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.1 | 0.077 (0.001) | |

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.5 | 0.040 (0.130) | |

| Altruism | 16 | 1.1 | 18 | 13.5 | 405 | 45.4 | 0.551 (0.000) | |

| 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 109 | 12.2 | 0.277 (0.000) | |

| Religious reasons | 10 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.028 (0.382) | |

| Personal belief | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 27 | 3.0 | 0.136 (0.000) | |

| 7 | 0.5 | 3 | 2.3 | 84 | 9.4 | 0.223 (0.000) | |

| Vocational affiliation | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 28 | 3.1 | 0.134 (0.000) | |

| Surrendering responsibility | 15 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.064 (0.006) | |

| Total n/domain (D05) | 57 | 3.8 | 26 | 19.5 | 633 | 70.9 | 0.702 (0.000) | |

| D06Image/Experience | n | % | n | % | n | % | Cramer’s V (p-Value) | |

| 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 2.3 | 64 | 7.2 | 0.203 (0.000) | |

| 31 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.092 (0.000) | |

| Try it out (curiosity motive) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.054 (0.026) | |

| No need present | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.040 (0.128) | |

| Rare blood type | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 14 | 1.6 | 0.096 (0.000) | |

| Advertisement/Campaign/Phone call/Appeal | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 26 | 2.9 | 0.131 (0.000) | |

| 11 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 45 | 5.0 | 0.142 (0.000) | |

| Absence of disadvantages | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 17 | 1.9 | 0.094 (0.000) | |

| D07 Benefits/Incentives | Total n/domain (D06) | 52 | 3.4 | 7 | 5.3 | 164 | 18.4 | 0.249 (0.000) |

| Blood donor card | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.047 (0.064) | |

| 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.5 | 61 | 6.8 | 0.196 (0.000) | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.6 | 0.101 (0.000) | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 2.4 | 0.124 (0.000) | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.0 | 0.081 (0.000) | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.6 | 0.101 (0.000) | |

| D08 Conditions | Total n/domain (D07) | 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.5 | 107 | 12.0 | 0.271 (0.000) |

| 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.020 (0.598) | |

| 7 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.018 (0.670) | |

| 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.0 | 0.046 (0.067) | |

| D09 Psychological Aspects | Total n/domain (D08) | 16 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.7 | 0.041 (0.126) |

| 23 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.075 (0.001) | |

| 18 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.065 (0.005) | |

| 126 | 8.4 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.187 (0.000) | |

| 53 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.117 (0.000) | |

| Not thought about it | 161 | 10.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.216 (0.000) | |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 42 | 4.7 | 0.163 (0.000) | |

| 10 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.052 (0.032) | |

| D10 Missing points of contact | Total n/domain (D09) | 386 | 25.8 | 3 | 2.4 | 43 | 4.8 | 0.278 (0.000) |

| No request/appellation/call | 26 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.078 (0.000) | |

| Missing reason/occasion | 18 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.070 (0.002) | |

| For no reason | 23 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.6 | 0.050 (0.040) | |

| Misc | Total n/domain (D10) | 67 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.7 | 0.114 (0.000) |

| Other | 13 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 11 | 1.2 | 0.018 (0.657) | |

| Do not know | 24 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.6 | 0.053 (0.031) | |

| Not specified | 162 | 10.8 | 16 | 12.0 | 29 | 3.2 | 0.134 (0.000) | |

| Total n/domain (D11) | 199 | 13.3 | 17 | 12.8 | 45 | 5.0 | 0.129 (0.000) | |

| (b) | ||||||||

| Domain (D)/Main Category | Subcategory | Non-Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Intenders (Next 12 Months) | Effect Size | ||||

| D01 Ineligibility | n | % | n | % | Phi | |||

| Unspecific reason | 20 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.059 (0.003) | |||

| Age | 284 | 16.5 | 5 | 0.7 | −0.225 (0.000) | ||

| Health | 337 | 19.6 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.254 (0.000) | |||

| Pregnancy | 7 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.035 (0.083) | |||

| Other | 14 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.1 | −0.040 (0.049) | ||

| D02 Impact/Effect | Total n/domain (D01) | 634 | 36.8 | 9 | 1.2 | −0.371 (0.000) | ||

| Positive | 2 | 0.1 | 12 | 1.6 | 0.092 (0.000) | ||

| Negative—health | 62 | 3.6 | 2 | 0.3 | −0.096 (0.000) | |||

| Negative—risk | 29 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.071 (0.000) | |||

| Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 2.6 | 0.135 (0.000) | ||

| Negative | 6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.032 (0.109) | |||

| D03 Fears/Aversion | ToTotal n/domain (D02) | 95 | 5.5 | 31 | 4.2 | −0.027 (0.181) | ||

| Fears in general | 40 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.084 (0.000) | ||

| Fear of the needle | 80 | 4.6 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.120 (0.000) | |||

| Fear of blood | 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.030 (0.144) | |||

| Fear to donate | 20 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.059 (0.003) | |||

| Fear of pain | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.019 (0.355) | |||

| Other | 11 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.1 | −0.033 (0.102) | |||

| Needles | 21 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.061 (0.003) | ||

| Blood | 27 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.069 (0.001) | |||

| Other | 21 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.3 | −0.045 (0.026) | |||

| D04 Obstacles/Barriers | Total n/domain (D03) | 205 | 11.9 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.189 (0.000) | ||

| 27 | 1.6 | 5 | 0.7 | −0.036 (0.076) | |||

| 18 | 1.0 | 10 | 1.4 | 0.014 (0.500) | |||

| 27 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.069 (0.001) | |||

| 128 | 7.4 | 20 | 2.7 | −0.091 (0.000) | |||

| 33 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.057 (0.004) | |||

| D05 Norms | Total n/domain (D04) | 209 | 12.1 | 36 | 4.9 | −0.111 (0.000) | ||

| General (if no other category) | 2 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.040 (0.049) | ||

| Future-orientated | 8 | 0.5 | 51 | 6.9 | 0.194 (0.000) | |||

| Past-orientated (self) | 1 | 0.1 | 8 | 1.1 | 0.078 (0.000) | |||

| Past-orientated (friends and family) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.031 (0.126) | |||

| 24 | 1.4 | 297 | 40.4 | 0.530 (0.000) | |||

| 7 | 0.4 | 69 | 9.4 | 0.238 (0.000) | |||

| 7 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | −0.022 (0.281) | |||

| 4 | 0.2 | 16 | 2.2 | 0.099 (0.000) | |||

| 3 | 0.2 | 77 | 10.5 | 0.266 (0.000) | |||

| 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.1 | 0.087 (0.000) | |||

| 25 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.066 (0.001) | |||

| Total n/domain (D05) | 77 | 4.5 | 474 | 64.5 | 0.659 (0.000) | |||

| D06Image and Experience | n | % | n | % | Phi | |||

| 2 | 0.1 | 68 | 9.3 | 0.251 (0.000) | |||

| 34 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.059 (0.004) | |||

| 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.044 (0.030) | |||

| 8 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | −0.025 (0.217) | |||

| 2 | 0.1 | 11 | 1.5 | 0.087 (0.000) | |||

| 3 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.032 (0.115) | |||

| 16 | 0.9 | 38 | 5.2 | 0.132 (0.000) | |||

| 3 | 0.2 | 30 | 4.1 | 0.155 (0.000) | |||

| D07 Benefits/Incentives | Total n/domain (D06) | 68 | 4.0 | 149 | 20.3 | 0.263 (0.000) | ||

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | - | |||

| 19 | 1.1 | 19 | 2.6 | 0.055 (0.006) | |||

| 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.031 (0.126) | |||

| 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.5 | 0.103 (0.000) | |||

| 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | - | |||

| 3 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.041 (0.044) | |||

| D08 Conditions | Total n/domain (D07) | 22 | 1.3 | 33 | 4.5 | 0.099 (0.000) | ||

| 5 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 | −0.002 (0.938) | |||

| 11 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.002 (0.907) | |||

| 8 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.005 (0.795) | |||

| D09 Psychological Aspects | Total n/domain (D08) | 22 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.5 | 0.009 (0.666) | ||

| 7 | 0.4 | 29 | 3.9 | 0.135 (0.000) | |||

| 17 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.3 | −0.037 (0.064) | |||

| 117 | 6.8 | 4 | 0.5 | −0.132 (0.000) | |||

| 36 | 2.1 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.062 (0.002) | |||

| 42 | 2.4 | 5 | 0.7 | −0.059 (0.004) | |||

| 5 | 0.3 | 18 | 2.4 | 0.103 (0.000) | |||

| 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | −0.037 (0.064) | |||

| D10 Missing points of contact | Total n/domain (D09) | 229 | 13.3 | 59 | 8.0 | −0.075 (0.000) | ||

| 11 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.5 | −0.006 (0.783) | |||

| 15 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | −0.042 (0.038) | |||

| 19 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.034 (0.094) | |||

| Misc | Total n/domain (D10) | 44 | 2.6 | 8 | 1.0 | −0.047 (0.021) | ||

| 16 | 0.9 | 9 | 1.2 | 0.013 (0.504) | |||

| 26 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.4 | −0.047 (0.021) | |||

| 241 | 14.0 | 48 | 6.5 | −0.106 (0.000) | |||

| Total n/domain (D11) | 283 | 16.4 | 60 | 8.1 | −0.109 (0.000) | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Greffin, K.; Schmidt, S.; Schönborn, L.; Muehlan, H. “Blood for Blood”? Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation in the German Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084238

Greffin K, Schmidt S, Schönborn L, Muehlan H. “Blood for Blood”? Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation in the German Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084238

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreffin, Klara, Silke Schmidt, Linda Schönborn, and Holger Muehlan. 2021. "“Blood for Blood”? Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation in the German Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084238

APA StyleGreffin, K., Schmidt, S., Schönborn, L., & Muehlan, H. (2021). “Blood for Blood”? Personal Motives and Deterrents for Blood Donation in the German Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084238