Abstract

Access to healthcare for adolescents is often overlooked in the United States due to federal and state-sponsored insurance programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. While these types of programs provide some relief, the issue of healthcare access goes beyond insurance coverage and includes an array of ecological factors that hinder youths from receiving services. The purpose of this scoping review was to identify social-ecological barriers to adolescents’ healthcare access and utilization in the United States. We followed the PRISMA and scoping review methodological framework to conduct a comprehensive literature search in eight electronic databases for peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2020. An inductive content analysis was performed to thematize the categories identified in the data extraction based on the Social-Ecological Model (SEM). Fifty studies were identified. Barriers across the five SEM levels emerged as primary themes within the literature, including intrapersonal-limited knowledge of and poor previous experiences with healthcare services, interpersonal-cultural and linguistic barriers, organizational-structural barriers in healthcare systems, community-social stigma, and policy-inadequate insurance coverage. Healthcare access for adolescents is a systems-level problem requiring a multifaceted approach that considers complex and adaptive behaviors.

1. Introduction

Healthcare is essential to the wellbeing of adolescents in the United States (U.S.). Access to healthcare is commonly associated with insurance coverage; therefore, the issue of adolescents’ access to healthcare is frequently minimized due to federal and state-sponsored coverage programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). However, healthcare access is more complex than just insurance coverage; it includes the availability of healthcare services, timeliness in treatment, and a competent workforce [1]. The majority of healthcare services are not designed with adolescent patients in mind; therefore, adolescents are at risk of not having a consistent source of care (services), are unable to get care when needed (timeliness), and often lack qualified, competent providers (workforce) that tailor care to their unique needs [2]. Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, researchers report that young adults have increased their use of preventive services via well visits (28% pre-ACA to 32% post-ACA) among most racial and ethnic groups [3]. Despite this improvement, less than half of all U.S. adolescents receive well visits, which is key to prevention [3].

Quality healthcare is vital during adolescence because preventive services can modify or deter risky behavior, encourage healthy habits, and promote overall health. Historically, low-income families were more likely to report problems getting their children necessary care and communicating with providers [2]. Youths from low-income families are also less likely to go to primary care providers or have medicine prescribed, but are more likely to use emergency care than middle-to-high-income families [2].

Services tailored specifically to the needs of adolescents are most beneficial. Youth-friendly healthcare services have been successfully embraced in countries with progressive healthcare policies, such as Sweden [4]. In these countries, youth-friendly services are those provided by clinicians who understand and are motivated to work with youths and are located in healthcare settings that ensure confidentiality and embrace a youth-centered approach [4]. These characteristics are important because adolescents often avoid or delay care for sensitive issues due to parental involvement and cite confidentiality as one of the main barriers to their use of healthcare services [4,5]. Furthermore, adolescents are more likely to disclose sensitive health information and return for care in the future if they are assured of confidentiality [5]. Despite this information, studies show that only 30 to 40% of adolescents report spending time alone with their providers during preventive care services, and less than 20% report receiving recommended counseling and screening for high-risk behaviors [6].

Although there is a need to identify barriers that affect youth access to healthcare, there have been no cited review studies that broadly identify these factors within the last ten years. Previous reviews either target specific healthcare services, particular subpopulations and/or include studies outside of the U.S. [7,8,9,10]. Barriers described in these studies focus on mental health services, sexual and reproductive health services, or focus on trafficked youth. While these studies are equally important, a holistic understanding of the barriers that prevent youth access to healthcare in the U.S. is needed.

The purpose of this study was to review the published empirical research on barriers to healthcare access and utilization of services by youths and young adults in the U.S. using the Social-Ecological Model (SEM). The study answered the following research question: “What are the barriers to healthcare access and utilization for adolescents and young adults?”

2. Materials and Methods

A scoping review was selected for the study methodology because it enables researchers to identify and map key concepts of existing literature of an under-researched and complex topic [11,12,13] Specifically, Munn and colleagues note that the goal of conducting a scoping review is to “provide an overview or map of the evidence” [11] (p. 3) as opposed to a systematic review, which is used to “produce a critically appraised and synthesized result/answer to a particular question” [11] (p. 3). The scoping review methodology was most appropriate for this study because of the dynamic and complex nature of human development during adolescence, the multifaceted healthcare barriers adolescents encounter, and the abundance of literature investigating adolescent health outcomes across several domains.

This study was guided by Colquhoun and colleagues’ enhanced methodological framework for scoping review [11]. The framework included the following stages: (1) clarifying and linking the purpose and research question(s), (2) identifying appropriate studies, (3) using an iterative team approach for selecting studies and extracting data, (4) incorporating a numerical analysis, (5) summarizing and reporting the study results, and (6) consultation.

2.1. Search Strategy

A preliminary search in Google Scholar was conducted in April 2020, which allowed the researchers to test search terms and extract relevant peer-reviewed literature regarding youth’s healthcare access and barriers in the 21st century. With the assistance of a research librarian, a comprehensive search was conducted using eight electronic databases: Child Development & Adolescent Studies, CINAHL Complete, Family & Society Studies Worldwide, Family Studies Abstracts, MEDLINE, ERIC, Mental Measurements Yearbook with Tests in Print, and Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. These databases were selected based on their inclusion of health-focused journals and broader social science content. An updated search was conducted in September 2020 and restricted to the past 10 years (2010 to 2020). Search terms were updated based on the findings from preliminary searches. They included (adolescents or teenagers or young adults or teen or youth) AND healthcare AND (barriers or obstacles or challenges) AND (access to care or access to healthcare or access to services) AND (United States or America or USA or U.S).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

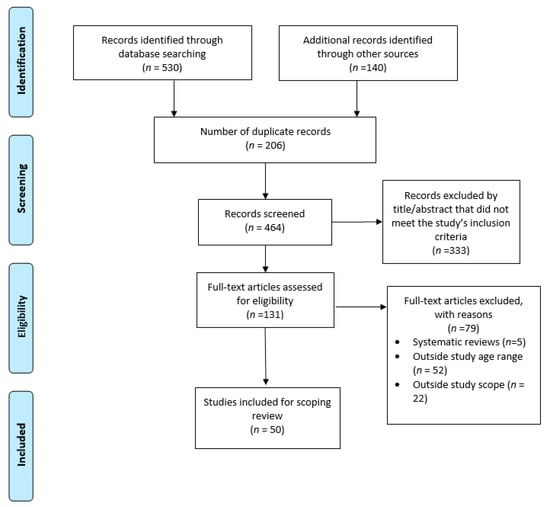

Quantitative, qualitative, and review studies reporting healthcare barriers, access, and utilization among U.S. young adults were included in the review. The included studies represented various healthcare settings, including hospitals, primary healthcare centers/clinics, and school-based health centers. We included studies that analyzed secondary data, evaluated interventions, and reported adolescents’ (10 to 24 years) health outcomes [14]. However, articles with children and young adults were selected if the adolescents’ percentage represented more than half of the study population. We excluded literature reviews and studies reporting outcomes unrelated to healthcare. For this study, we operationalized our study population (adolescents/teenagers and young adults) based on guidelines by the World Health Organization (WHO) and evidence from the literature [14,15]. As such, our study includes articles with persons less than and up to 31 years old, with the majority being during the adolescent years (10 to 24 years). This allowed us to capture all relevant data points about our study population—see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included articles for scoping review.

2.3. Data Abstraction

Following the scoping review framework, we iteratively abstracted data points using a matrix method [16]. Factors associated with adolescents’ and young adults’ healthcare access and barriers to access were extracted from each study. The screening was conducted in two phases. In phase one, two reviewers independently screened the articles by abstract/title and full text. Extracted points assessed include, but are not limited to, the year of publication, study design, study type, type of care, target population, barriers to access, study setting, and proposed solutions (if mentioned). The raters collaboratively coded the contents using a thematic synthesis and discussed differences identified within the final articles. In phase two, the researchers collaboratively coded the data using a thematic synthesis strategy where key themes identified within the results and discussion of each article were inputted into an Excel database and manually coded to reflect more broader categories. These broad categories were then classified based on their correspondence with the social ecological level of the SEM.

2.4. Data Organization Using the Social-Ecological Model

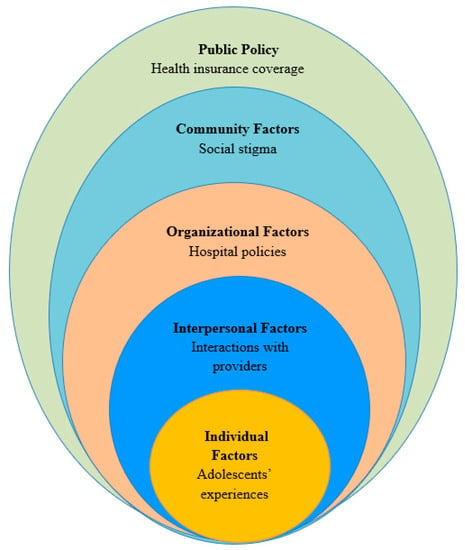

The SEM posits that individual health behavior influences and is influenced by characteristics within the environment [17]. In this framework, individuals are positioned within multiple hierarchical levels of influence (e.g., intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy)—see Figure 2. This multifaceted perspective is useful when understanding complex issues such as youth access and healthcare experience. For example, we can use this model to identify and examine relationships between factors that affect youth’s access and experience with services (e.g., knowledge, patient–provider relationships, ability to pay for services, etc.). A social-ecological approach also emphasizes opportunities for comprehensive, multilevel interventions whose effects are more likely to be sustained [18,19].

Figure 2.

Factors influencing access to care for adolescents.

The Social-Ecological Model for health promotion shows the multilevel factors within the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy level that affect adolescents’ access to care in the U.S.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

Overall, 50 studies were included using an inductive content analysis approach. The majority of studies took place within community-based, primary care settings (i.e., outside of school settings; n = 46; 92%). Others took place in school-based health centers and pharmacies (n = 2; 4%). Additionally, half of the studies focused on general healthcare (n = 25; 50%), a little less than half concentrated on specialized healthcare (e.g., oncology; n = 17; 34%), followed by reproductive healthcare (n = 6; 12%), and behavioral healthcare (n = 2; 4%). The reported health needs in the articles varied. The majority of reported barriers related to youth’s general healthcare needs (n = 30; 60%), specialized healthcare needs (e.g., HIV, diabetes, or sickle cell disease; n = 19; 38%), and a small number reported the needs of homeless and runaway youths (n = 3; 6%). A detailed description of the study’s characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Articles for Scoping Review.

3.2. Primary Themes: Barriers to Care

In the following sections, we describe the barriers to youth healthcare access, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Barriers to Access to Care for Adolescents according to the Social-Ecological Model.

3.2.1. Individual Level Factors

Individual level factors, also referred to as intrapersonal factors, are associated with individuals’ characteristics, including knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and skills [17]. In our study, the most cited individual level barriers to access included lack of knowledge of healthcare services and negative beliefs about and experiences with past care (n = 18). Some examples include limited knowledge about services, vaccines, and other resources; having prior experience with unmet treatment needs; and personal beliefs about the risk of disease and safety related to vaccines. Navigation of services, including follow-up and adherence, posed the next greatest barrier (n = 9). This includes lack of knowledge of steps to take to seek care, attendance at follow-up visits, adherence to prescription medication, and navigation of continuation of care given life transitions. Finally, racial disparities (n = 7) and socioeconomic status (n = 6) were also reported as barriers to healthcare access for youth.

3.2.2. Interpersonal Level Factors

Interpersonal level factors are characterized by interactions with others, including formal and informal social networks and social support systems; [17] in this study, we examined interpersonal factors between patients and healthcare providers. Cultural and linguistic barriers presented the greatest barrier at the interpersonal level (n = 10). These barriers were based on communication challenges, including patients and families with limited English proficiency. Immigration status, cultural differences, and discrimination also contributed to these types of interpersonal barriers. The relationship or lack thereof between patients and providers also posed an obstacle for youths seeking care (n = 8). This included poor decision-making on part of the provider, inadequate recommendations for vaccines, and neglect of patients’ physical, mental, and developmental needs.

3.2.3. Organizational Level Factors

Organizational or institutional factors encompass social institutions’ characteristics, including their formal and informal rules and regulations for operation [17]. For this study, we focused on institutional factors within the healthcare system. Of all barriers identified, structural barriers at the organization level were noted as the most significant to impede youth access to healthcare services (n = 32). Within this category, limited organizational resources, including drug shortages, clinic space, and shared electronic health records across different types of care, created barriers for adolescent patients when seeking care. Long wait times, lack of organizational regard for barriers to care for youth, and poor coordination of care across different providers also contributed to structural barriers. Financial barriers based on the cost of care were identified as barriers at the organizational level (n = 18). A lack of free medical services, families’ inability to afford copays, and high costs of care all contributed to financial barriers. Organizations’ inability to provide confidential services also contributed to barriers youths faced when seeking care (n = 8). For example, billing procedures and service statements created privacy concerns for youths because they may reveal health service utilization to parents or caregivers. Lastly, barriers related to physical space within the healthcare setting also prevented youths from engaging in healthcare services (n = 4).

3.2.4. Community Level Factors

Within a set boundary, relationships between organizations, institutions, and informal networks comprise community level factors [17]. The primary barrier identified at the community level was the stigma of care-seeking behaviors. Studies report that youths expressed concern with being judged for seeking services (n = 8). The stigma around mental health, incarcerated youth, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, sexual minorities, and sex, in general, were all cited as examples. Transportation to and from clinics, as well as the distance from clinics, also prevented youths from being able to access services (n = 7).

3.2.5. Policy Level Factors

Policy level factors include local, state, and national laws and policies [17]. At the policy level, two key themes emerged. The first, insurance coverage (n = 20), posed barriers for youths that did not have insurance and even youths with insurance. For youths with insurance, their insurance denied payment or caused delays due to prior authorization requests. This barrier was described with both public and private insurance coverage, limiting young people’s ability to access care regardless of insurance type. Finally, consent policies also impacted youths’ comfort level with seeking care (n = 4) primarily because healthcare systems require parent or guardian consent for services. These policies are typically determined at the state level and premised with the idea that parents or guardians seek their child’s best interests. However, more stringent consent laws hinder youths from seeking care due to fear that their parents or guardians will learn about the types of services they desire.

3.3. Secondary Theme: Facilitators to Care

Table 3 shows the facilitators to care and proposed solutions based on the social-ecological level. Less than half of the studies assessed proposed solutions to the barriers identified. The most recurring solution required changes to the healthcare system (n = 16). Examples include a coordinated care model that improves youth access to different services, using technology to capture health information, establishing culturally and linguistically appropriate service standards, and providing alternative, more easily accessible sites for preventive visits. Outreach was also mentioned as a possible solution (n = 8) and included ways to disseminate information related to the types of services offered and the necessity for preventive visits, including vaccines. Studies also discussed youth-friendly strategies to remove barriers to accessing care (n = 3). These included web-based technologies that are youth-centered, creating social support systems for youths, and using developmentally appropriate interventions. Lastly, two studies proposed that providing financing options for youths could remove barriers to the cost of care.

Table 3.

Facilitators to Access to Care for Adolescents.

4. Discussion

This scoping review provides significant insight into the barriers adolescents face when accessing and utilizing healthcare services in the U.S. Given the range of findings across all SEM levels, it is clear that healthcare access for adolescents is a systems-level problem. The complexity of the issue is underscored by multiple influencing factors that are interrelated. Based on the literature, there is no single solution to expanding access for adolescents in the U.S.; rather, a multifaceted approach that considers the complex and adaptive behaviors of interacting factors must be considered. Additionally, our study provided a holistic understanding of the barriers youths face when accessing care, regardless of the context. While we did not differentiate between rural, suburban, and urban settings, the barriers identified in this study can be applied across settings, with the understanding that these barriers may be and are likely augmented in rural settings [70].

The most commonly cited barriers to the utilization of services across the published literature occurred at the organizational level. These barriers were structural and prohibited youths from accessing timely, quality health services. A lack of organizational resources for providing prevention and treatment (drugs, space, technology), long wait times, poor organizational policies, and a lack of coordinated care contributed to these structural barriers. This finding is also supported by the proposed solutions identified, including more coordinated care and applying youth-friendly methods to care provision.

Consistent with the literature, our study also found that the cost of care related to the type or lack of health insurance at the organizational and policy levels presented a significant barrier to obtaining healthcare services [71,72]. It should be noted that the cost of services themselves is not simply what creates these barriers; the capacity to pay for these services also contributes to the issue [73]. The passing of the ACA attempted to address this barrier through the provision of covered preventive health services; however, the structure and financing of adolescent healthcare, including high costs related to treatment, allow inequities in coverage and access to persist, especially among racial and ethnic minorities [74]. Youths need free or low-cost medical services to overcome families’ lack of insurance, inability to afford copays, and overall high costs of care. It should be noted that the cost of care as a barrier to healthcare is not unique to youths alone but a common theme across all age groups in the U.S. For instance, the U.S. ranks higher than most developed nations with seniors (people aged 65 above) unable to access primary care due to cost constraints [72]. Similarly, a large proportion of American adults, irrespective of income levels, reported that the high cost of care makes quality care unaffordable [71]. This indicates that healthcare costs are an inherent barrier to securing quality healthcare in the U.S.

Our study also revealed that several individual-level factors, such as knowledge and awareness of services and cultural beliefs, negatively impacted youths in receiving services and their ability to comprehend treatment and diagnosis. Studies across several health domains and population subgroups have reported similar findings. For example, patients with mental health illness have poor knowledge about available treatment services [6,40]. Moreover, culture plays a significant role in utilizing healthcare services among mentally ill patients [75]. This observation emphasizes the need to address these types of barriers. For example, culturally tailored interventions and innovative health education practices can mitigate disparities to care [76].

Furthermore, our analysis revealed that parental consent laws were a major barrier to youth access and utilization of healthcare services. Consent policies are typically established at the state level and enforced in varying degrees by providers [66]. These laws and the legally defined age for which a minor can provide consent for their care varies significantly by state [77]. For example, concerning abortion services for minors, state mandates and laws differ significantly [78]. Nonetheless, mandates and legislations act as barriers not only to abortion services but also to receiving access to optimal healthcare [79,80].

4.1. Future Directions

This scoping review establishes a direction for future research and intervention development. A systems perspective to design interventions that focus on access to healthcare among adolescents is necessary and essential to addressing this public health issue. A systems perspective encourages collaboration among multidisciplinary teams across the social-ecological levels. Multidisciplinary teams that include content experts, providers, and youths themselves must work together to design solutions. Context experts are also important stakeholders that could provide insight into the ways in which local, community-based settings, especially in rural areas, create or remove barriers related to healthcare access. Organizational partners must also be included to address structural barriers to access to improve future interventions. Lastly, interventions must be ecological in their design to address barriers to care adequately. Research shows that designing interventions to improve positive health behaviors among adolescents using the social-ecological framework is effective [81]. Despite these recommendations, caution is also needed. As a systems-level problem, changing any of these influencing factors will impact the entire system. Unintended consequences should be considered in an effort to avoid negative outcomes of interventions.

4.2. Limitations

As per the inclusion criteria, studies that included children (<10 years of age) and young adults (>24 years of age) were included in this review. The data from children, adolescents, and/or young adults were pooled, so it was impossible to specifically extract findings targeted at youths or adolescents. This expanded the study’s scope, but the results may not be generalizable for the target population. Researchers attempted to account for this by only including studies where adolescents made up most of the study population. This review also included studies that occurred in highly specific settings and particular subpopulations, which further affected the results’ generalizability. Although this can be limiting, adolescent health needs and issues are heterogeneous, so to adequately capture the most significant barriers faced, it is necessary to pool these findings.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to determine the most cited barriers to youth access to healthcare within the literature. The classification of identified barriers on a social-ecological level brings to light the complexity of this issue and emphasizes that there is not a simple solution to address it. The most cited barriers identified were structural barriers within the healthcare system; barriers posed by policies related to insurance coverage or lack of coverage; individuals’ knowledge, experience, and beliefs about the healthcare system; and financial barriers at the organizational level. The information gleaned from this study indicates that barriers to healthcare access for youths constitutes multiple ecological levels, and thus, requires a holistic approach to promote optimal health for youths and improve their health outcomes later in life. Future research and program models should be systems-based and include multidisciplinary teams to address the complex nature of healthcare access for adolescents.

Author Contributions

W.G.—conceptualization, method, methodology, writing, and editing. K.V.A. & S.P.—method, methodology, writing, and editing. K.W., S.M.L., S.F., K.G., C.E.—writing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of Population Affairs under grant number [AH-TP2-20-002]—Tier 2 Innovation and Impact Network Grants: Achieving Optimal Health and Preventing Teen Pregnancy in Key Priority Areas. Its contents are solely the authors’ responsibility and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services or the Office of Population Affairs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Elements of Access to Healthcare. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/access/elements.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Simpson, L.; Owens, P.L.; Zodet, M.W.; Chevarley, F.M.; Dougherty, D.; Elixhauser, A.; McCormick, M.C. Health Care for Children and Youth in the United States: Annual Report on Patterns of Coverage, Utilization, Quality and Expenditures by Income. Ambul. Pediatr. 2005, 5, 6-e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.H.; Park, M.J.; Twietmeyer, L.; Brindis, C.D.; Irwin, C.E. Young Adult Preventive Healthcare: Changes in Receipt of Care Pre- to Post-Affordable Care Act. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomée, S.; Malm, D.; Christianson, M.; Hurtig, A.K.; Wiklund, M.; Waenerlund, A.K.; Goicolea, I. Challenges and Strategies for Sustaining Youth-Friendly Health Services—A Qualitative Study from the Perspective of Professionals at Youth Clinics in Northern Sweden. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, A.L.; Rickert, V.I.; Aalsma, M.C. Clinical Conversations about Health: The Impact of Confidentiality in Preventive Adolescent Care. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, C.E.; Adams, S.H.; Jane Park, M.; Newacheck, P.W. Preventive Care for Adolescents: Few Get Visits and Fewer Get Services What’s Known on This Subject. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Mental Health Help-Seeking in Young People: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.S.; Fulbright, Y.K. Content Analysis: A Review of Perceived Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services by Young People. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2013, 18, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, A.W.; Loyola Briceno, A.C.; Pazol, K.; Zapata, L.B.; Decker, E.; Rollison, J.M.; Malcolm, N.M.; Romero, L.M.; Koumans, E.H. Youth-Friendly Family Planning Services for Young People: A Systematic Review Update. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Panda, P.; Neudecker, M.; Lee, S. Barriers to the Access and Utilization of Healthcare for Trafficked Youth: A Systematic Review. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 100, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The Age of Adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. Available online: https://doi.org/https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Garrard, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy, 6th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mcleroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Heal. Educ. Behav. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diclemente, R.J.; Salazar, L.F.; Crosby, R.A. A Review of STD/HIV Preventive Interventions for Adolescents: Sustaining Effects Using an Ecological Approach. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2007, 32, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, M.J.; Knauer, H.A.; Calvin, K.E.; Takayama, J.I. Caring for Children with Special Health Care Needs: Profiling Pediatricians and Their Health Care Resources. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbin, M.M.; Tanner, A.E.; DuVal, A.; Ellen, J.; Kapogiannis, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. Linking HIV-Positive Adolescents to Care in 15 Different Clinics across the United States: Creating Solutions to Address Structural Barriers for Linkage to Care. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimanpour, S.; Geierstanger, S.P.; Kaller, S.; Mccarter, V.; Brindis, C.D. The Role of School Health Centers in Health Care Access and Client Outcomes. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.A.; Fahey, N.; Shields, C.; Suther, E.; Cabral, H.J.; Silverstein, M. Pharmacy Communication to Adolescents and Their Physicians Regarding Access to Emergency Contraception. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, T.; Jadwin-Cakmak, L.; Popoff, E.; Reisner, S.L.; Campbell, B.A.; Harper, G.W. Stigma, Gender Affirmation, and Primary Healthcare Use Among Black Transgender Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rider, G.N.; Mcmorris, B.J.; Gower, A.L.; Coleman, E.; Eisenberg, M.E. Health and Care Utilization of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20171683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacApagal, K.; Bhatia, R.; Greene, G.J. Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences Within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggio, S.; Tran, N.T.; Barnert, E.S.; Gétaz, L.; Heller, P.; Wolff, H. Lack of Health Insurance among Juvenile Offenders: A Predictor of Inappropriate Healthcare Use and Reincarceration? Public Health 2019, 166, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, J.W.; Ph, D.; Gilman, S.E.; Sc, D.; Haynie, D.L.; Ph, D.; H, M.P.; Simons-morton, B.G.; Ed, D.; H, M.P. Sexual Orientation Differences in Adolescent Health Care Access and Health-Promoting Physician Advice. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelvakumar, G.; Ford, N.; Kapa, H.M.; Lange, H.L.H.; Laurie, A.; Andrea, M. Healthcare Barriers and Utilization Among Adolescents and Young Adults Accessing Services for Homeless and Runaway Youth. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmanus, M.A.; Pollack, L.R.; Cooley, W.C.; Mcallister, J.W.; Lotstein, D.; Strickland, B.; Mann, M.Y. Current Status of Transition Preparation Among Youth With Special Needs in the United States. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, A.E.; Philbin, M.M.; Chambers, B.D.; Ma, A.; Hussen, S.; Ware, S.; Lee, S.; Fortenberry, J.D. Healthcare Transition for Youth Living with HIV: Outcomes from a Prospective Multi-Site Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, J.M.; Seid, M.; Waitzfelder, B.; Anderson, A.M.; Beavers, D.P.; Dabelea, D.M.; Dolan, L.M.; Imperatore, G.; Marcovina, S.; Reynolds, K.; et al. Prevalence of and Disparities in Barriers to Care Experienced by Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1369–1375.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Oza-Frank, R.A., Jr.; Dolan, L.M.; Dabelea, D.; Lawrence, J.M.; Pihoker, C.; Rebecca, M.O.; Linder, B.; Imperatore, G.; Seid, M.; et al. Migration Status in Relation to Clinical Characteristics and Barriers to Care Among Youth with Diabetes in the US. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, S.L.; Yanni, E.A.; Creary, M.S.; Olney, R.S. Health Status and Healthcare Use in a National Sample of Children with Sickle Cell Disease. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, S528–S535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.L.; Jerman, J.; Ethier, K.; Moskosky, S. Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Teens and Young Adults: Youth-Friendly and Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Services in U.S. Family Planning Facilities. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, L.J.; Brindis, C.D. Access to Reproductive Healthcare for Adolescents: Establishing Healthy Behaviors at a Critical Juncture in the Lifecourse. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 22, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, B.B.; Jones, J.R.; Ghandour, R.M.; Kogan, M.D.; Newacheck, P.W. The Medical Home: Health Care Access and Impact for Children and Youth in the United States. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, J.Y.; Gruber, J.F.; Kepka, D.; Kunwar, M.; Smith, S.B.; Rothholz, M.C.; Brewer, N.T.; Smith, J.S. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics Pharmacist Insights into Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Provision in the United States Pharmacist Insights into Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Provision in the United States. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, J.; Kenney, M.K.; Ghandour, R.; Koplitz, M.; Silcott, S. CSHCN with Hearing Difficulties: Disparities in Access and Quality of Care. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, M.T.; Whitney, K.D.; Virata, M.C.D.; Binger, M.M.; Miller, E. A Web-Based Personal Health Information System for Homeless Youth and Young Adults. Public Health Nurs. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Guo, S.; Ijadi-Maghsoodi, R.; Puffer, M.; Kataoka, S.H. Bringing Wellness to Schools: Opportunities for and Challenges to Mental Health Integration in School-Based Health Centers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallum-Montes, R.; Middleton, D.; Schlanger, K.; Romero, L. Barriers and Facilitators to Health Center Implementation of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices in Adolescent Reproductive Health Services. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mullins, T.L.K.; Zimet, G.; Lally, M.; Kahn, J.A. Adolescent Human Immunodeficiency Virus Care Providers’ Attitudes Toward the Use of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016, 30, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, K.M. Barriers Latino Patients Face in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, O.D.; McDermott, S.; Mann, J.R.; Hardin, J.W.; Royer, J.A.; Ouyang, L. Disparities in Health Care Utilization by Race among Teenagers and Young Adults with Muscular Dystrophy. Med. Care 2014, 52, S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Chiaramonte, D.; Strzyzykowski, T.; Sharma, D.; Anderson-Carpenter, K.; Fortenberry, J.D. Improving Timely Linkage to Care among Newly Diagnosed HIV-Infected Youth: Results of SMILE. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossbard, J.R.; Lehavot, K.; Hoerster, K.D.; Jakupcak, M.; Seal, K.H.; Simpson, T.L. Relationships Among Veteran Status, Gender, and Key Health Indicators in a National Young Adult Sample. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, A.L.; Nyamathi, A.; Greengold, B.; Slagle, A.; Koniak-Griffin, D.; Khalilifard, F.; Getzoff, D. Health-Seeking Challenges among Homeless Youth. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, S.J.; Merchant, R.C.; Clark, M.A.; Liu, T.; Rosenberger, J.G.; Bauermeister, J.; Mayer, K.H. Potential Healthcare Insurance and Provider Barriers to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Utilization among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017, 31, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessett, D.; Prager, J.; Havard, J.; Murphy, D.J.; Agénor, M.; Foster, A.M. Barriers to Contraceptive Access after Health Care Reform: Experiences of Young Adults in Massachusetts. Womens Health Issues 2015, 25, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Peskoe, S.; Parmer, M.; Eddy, N.; Howe, J.; Fitzgerald, T.N. Children with Appendicitis on the US–Mexico Border Have Socioeconomic Challenges and Are Best Served by a Freestanding Children’s Hospital. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, L.P.; Kenney, M.K.; Denboba, D.; Strickland, B. Family Perceptions of Shared Decision-Making with Health Care Providers: Results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009–2010. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, A.R.; French, B.; Aysola, J.; Saloner, B.; Noonan, K.G.; Rubin, D.M. Quality of Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care for Children in Low-Income Families. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.J.; Keyser-Marcus, L.; Snipes, D.; Benotsch, E.; Sood, B. Perceived Mental Health Treatment Need and Substance Use Correlates Among Young Adults. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macqueen, K.M.; Chen, M.; Jolly, D.; Mueller, M.P.; Okumu, E.; Eley, N.T.; Laws, M.; Isler, M.R.; Kalloo, A.; Rogers, R.C. HIV Testing Experience and Risk Behavior Among Sexually Active Black Young Adults: A CBPR-Based Study Using Respondent-Driven Sampling in Durham, North Carolina. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, R.M.; Bramlett, M.D. Language and Immigrant Status Effects on Disparities in Hispanic Children’s Health Status and Access to Health Care. Matern. Child Health J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszka, J.B.; Lindell, D.; Killion, C.C.S. “It’s Like Pay Or Don’t Have It and Now I’m Doing Without” The Voice of Transitional Uninsured Former Foster Youth. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, K.; Beyer, W.J.; Wong, C.F.; Kipke, M.D. Engaging Young Men in the Hiv Prevention and Care Continua: Experiences from Young Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2019, 31, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; To, T.M.; Ling, I.; Melo, J.; Chavarin, J. The Influence of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals on Undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander Young Adults: Through a Social Determinants of Health Lens. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monz, B.U.; Houghton, R.; Law, K.; Loss, G. Treatment Patterns in Children with Autism in the United States. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.J.; Sung, L.; Dickens, D.S. Barriers to Medication Access in Pediatric Oncology in the United States. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 41, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Connor, C.G.; Ruedy, K.J.; Beck, R.W.; Kollman, C.; Buckingham, B.; Redondo, M.J.; Schatz, D.; Haro, H.; Lee, J.M.; et al. Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Treatment Center Are Associated with Insulin Pump Therapy in Youth in the First Year Following Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2013, 15, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.; Stratton, E.; Esiashvili, N.; Mertens, A.; Vanderpool, R.C. Providers’ Perspectives of Survivorship Care for Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, S.J.; Mallory, C.; Malin, M. Parental Consent and Access to Oral Health Care for Adolescents. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 18, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheak-Zamora, N.C.; Yang, X.; Farmer, J.E.; Clark, M. Disparities in Transition Planning for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Gebel, C.; Vargas, C.; Geltman, P.; Walter, A.; Garcia, R.I.; Tinanoff, N. Integration of Oral Health into the Well-Child Visit at Federally Qualified Health Centers: Study of 6 Clinics, August 2014–March 2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, 160066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaplan, D.W. Barriers and Potential Solutions to Increasing Immunization Rates in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, S24–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, S.A.; Fortin, K. Physical Health Problems and Barriers to Optimal Health Care among Children in Foster Care. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2015, 45, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeton, V.F.; Chen, A.K. Immunization Updates and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2010, 22, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, K.L.; Stewart, M.W. Effectiveness of School-Based Health Center Delivery of a Cognitive Skills Building Intervention in Young, Rural Adolescents: Potential Applications for Addiction and Mood. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 47, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Americans are Closely Divided Over Value of Medical Treatments, But Most Agree Costs are A Big Problem. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/09/americans-are-closely-divided-over-value-of-medical-treatments-but-most-agree-costs-are-a-big-problem/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Pew Research Center. Health Affairs: Among 11 nations, American Seniors Struggle More with Health Costs. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/03/health-affairs-among-11-nations-american-seniors-struggle-more-with-health-costs/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-Centred Access to Health Care: Conceptualising Access at the Interface of Health Systems and Populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebb, K.P.; Sedlander, E.; Bausch, S.; Brindis, C.D. Opportunities and Challenges for Adolescent Health Under the Affordable Care Act. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Nguyen, H.; Weiss, B.; Ngo, V.K.; Lau, A.S. Linkages between Mental Health Need and Help-Seeking Behavior among Adolescents: Moderating Role of Ethnicity and Cultural Values. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, F.F.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Gonzalvez, A.; Alderson, G.; Harthun, M.; Ayers, S.; Nuño Gutiérrez, B.; Corona, M.D.; Mendoza Melendez, M.A.; Kulis, S. Binational Cultural Adaptation of the Keepin’ It REAL Substance Use Prevention Program for Adolescents in Mexico. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Minors’ Consent Laws. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/minors.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Guttmacher Institute. Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortions. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/parental-involvement-minors-abortions (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Braverman, P.K.; Adelman, W.P.; Alderman, E.M.; Breuner, C.C.; Levine, D.A.; Marcell, A.V.; O’Brien, R. The Adolescent’s Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20163861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslyanskaya, S.; Alderman, E.M. Confidentiality and Consent in the Care of the Adolescent Patient. Pediatr. Rev. 2019, 40, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aura, A.; Sormunen, M.; Tossavainen, K. The Relation of Socio-Ecological Factors to Adolescents’ Health-Related Behaviour: A Literature Review. Health Educ. 2016, 77–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).