Sex Worker Health Outcomes in High-Income Countries of Varied Regulatory Environments: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

2.2. Information Sources

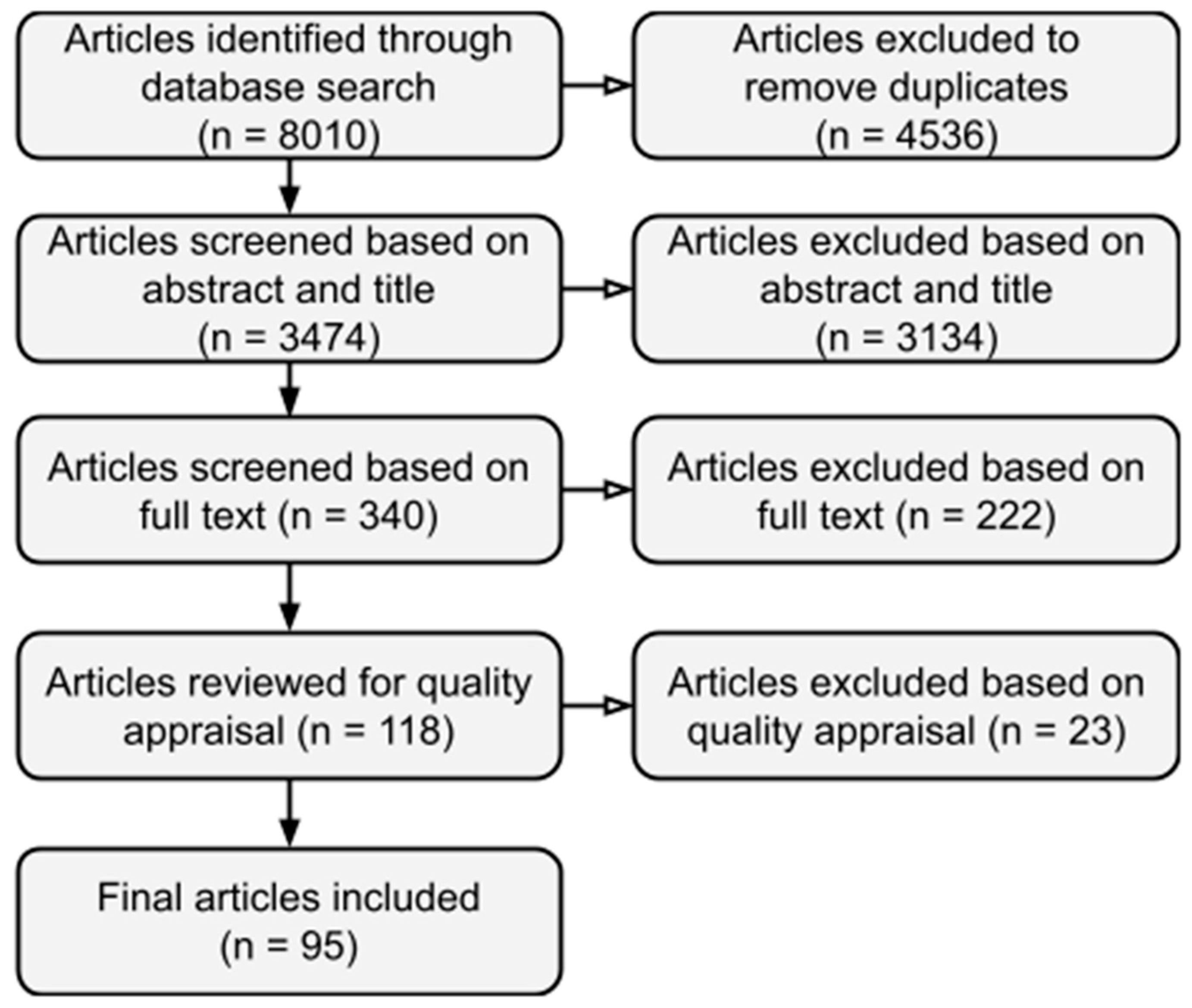

2.3. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

- Full criminalization: Legislation whereby all aspects of sex work and sex work locations and/or establishments are prohibited.

- Partial criminalization: Organisation of sex work is prohibited (e.g., involvement of third parties or running a brothel).

- ‘Nordic model’: Criminalization of purchase of sex and third parties.

- Legal: Regulatory models whereby sex work and sex work locations and/or establishments are legal (e.g., using a licencing or registration model).

- Decriminalization: Legislation whereby sex work and sex work locations and/or establishments are decriminalized. Criminal law may remain surrounding safe sex practices.

3. Results

3.1. Study Location

3.2. Legislation

3.3. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Study Design

3.5. Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shannon, K.; Strathdee, S.; Goldenberg, S.M.; Duff, P.; Mwangi, P.; Rusakova, M.; Reza-Paul, S.; Lau, J.; Deering, K.; Pickles, M.R.; et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. Lancet 2015, 385, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyrer, C.; Crago, A.-L.; Bekker, L.-G.; Butler, J.; Shannon, K.; Kerrigan, D.; Decker, M.R.; Baral, S.D.; Poteat, T.; Wirtz, A.L.; et al. An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. Lancet 2015, 385, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.W.; Crisp, B.R.; Mansson, S.A.; Hawkes, S. Occupational health and safety among commercial sex workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2012, 38, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Sanders, T.; Scoular, J.; Pitcher, J.; Cunningham, S. Risking safety and rights: Online sex work, crimes and ‘blended safety repertoires’. Br. J. Sociol. 2019, 70, 1539–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvey, L.; Hallett, J.; Lobo, R.; McCausland, K.; Bates, J.; Donovan, B. Western Australian Law and Sex Worker Health (LASH) Study Final Report. A Report to the Western Australian Department of Health; School of Public Health, Curtin University: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, M.R.; Crago, A.-L.; Chu, S.K.H.; Sherman, S.G.; Seshu, M.S.; Buthelezi, K.; Dhaliwal, M.; Beyrer, C. Human rights violations against sex workers: Burden and effect on HIV. Lancet 2015, 385, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.; Leyva, R.; Kwan, M.-P.; Magis, C.; Stainez-Orozco, H.; Brouwer, K. Women in sex work and the risk environment: Agency, risk perception, and management in the sex work environments of two Mexico-US border cities. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2019, 16, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Stanton, B. Alcohol use among female sex workers and male clients: An integrative review of global literature. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010, 45, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.K.; Consavage, K.E.; Dhanuka, I.; Clement, K.W.; Bouey, J.H. Health and health care access barriers among transgender women engaged in sex work: A synthesis of US-based studies published 2005–2019. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.D.; Lemus, H.; Wagner, K.D.; Martinez, G.; Lozada, R.; Gómez, R.M.G.; Strathdee, S.A. Factors associated with pathways toward concurrent sex work and injection drug use among female sex workers who inject drugs in northern Mexico. Addiction 2013, 108, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, C.; McCarthy, B.; Jansson, M. Stigma, sex work, and substance use: A comparative analysis. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, D.A.; Meffert, B.N.; Read, K.; Heinz, A.J. Culturally competent health care for sex workers: An examination of myths that stigmatize sex work and hinder access to care. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 34, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, E.; Matthews, K.; Thomas, A. HIV criminalisation and sex work in Australia. Reprod. Health Matters 2010, 18, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weitzer, R. Legalizing prostitution: Morality politics in Western Australia. Br. J. Criminol. 2009, 49, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P.; Sanders, T.; Scoular, J. Prostitution policy, morality and the precautionary principle. Drugs Alcohol Today 2016, 16, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoular, J. What’s law got to do with it? How and why law matters in the regulation of sex work. J. Law Soc. 2010, 37, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.D.; Tuminez, A.S. Reframing the interpretation of sex worker health: A behavioral-structural approach. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, S1206–S1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, G.M. A decade of decriminalization: Sex work ‘down under’ but not underground. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2014, 14, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisman, K. Let’s talk about sex: A three-way comparison of government-sanctioned prostitution. USUR J. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huglstad, M.; Halvorsen, I.L.I.; Jonsson, H.; Nielsen, K.T. “Some of us actually choose to do this”: The meanings of sex work from the perspective of female sex workers in Denmark. J. Occup. Sci. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.; Grenfell, P.; Meiksin, R.; Elmes, J.; Sherman, S.G.; Sanders, T.; Mwangi, P.; Crago, A.-L. Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, B.; Harcourt, C.; Egger, S.; Watchirs Smith, L.; Schneider, K.; Wand, H.; Kaldor, J.; Chen, M.; Fairley, C.K.; Tabrizi, S. The Sex Industry in New South Wales: A Report to the NSW Ministry of Health, Unpublished. 2012.

- Cunningham, S.; Shah, M. Decriminalizing indoor prostitution: Implications for sexual violence and public health. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2018, 85, 1683–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, G.M.; Fitzgerald, L.J.; Brunton, C. The impact of decriminalisation on the number of sex workers in New Zealand. J. Soc. Policy 2009, 38, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gordon, B.; Wijers, M.; Jobe, A. Justice and Civil Liberties on Sex Work in Contemporary International Human Rights Law. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckert, C.; Hannem, S. Rethinking the prostitution debates: Transcending structural stigma in systemic responses to sex work. Can. J. Law Soc. 2013, 28, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, C.; O’Connor, J.; Egger, S.; Fairley, C.K.; Wand, H.; Chen, M.Y.; Marshall, L.; Kaldor, J.M.; Donovan, B. The decriminalisation of prostitution is associated with better coverage of health promotion programs for sex workers. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, C.; Donovan, B.; Yeung, A.; de Visser, R.O.; Grulich, A.; Simpson, J.M.; Richters, J. Decriminalization of sex work Is not associated with more men paying for sex: Results from the second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy J. NSRC SR SP 2017, 14, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, C.; Dabbhadatta, J.; Harcourt, C.; Tribe, K.; O’Connor, C. Demographic, migration status, and work-related changes in Asian female sex workers surveyed in Sydney, 1993 and 2003. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2006, 30, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian Government. Review Into Decriminalisation of Sex Work; Victorian Government: East Melbourne, Australia, 2020.

- Northern Territory Government. Historic Legislation Passed: Northern Territory Sex Industry Bill 2019; Northern Territory Government: Parliament House, Australia, 2019.

- Statutes Amendment (Decriminalisation of Sex Work) Bill 2018; Government of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2018.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Carpenter, B.; O’Brien, E.; Hayes, S.; Death, J. Harm, responsibility, age, and consent. New Crim. Law Rev. 2014, 17, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quennerstedt, A.; Robinson, C.; I’Anson, J. The UNCRC: The voice of global consensus on children’s rights? Nord. J. Hum. Rights 2018, 36, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 Edition; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, J.; Crawford, G.; Portsmouth, L.; Jancey, J.; Leaversuch, F.; Nimmo, L.; Hunt, K. Recreational drowning prevention interventions for adults, 1990–2012: A review. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.; Lobo, R.; Brown, G.; Macri, C.; Smith, H.; Maycock, B. HIV, other blood-borne viruses and sexually transmitted infections amongst expatriates and travellers to low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, M.M.; Dos Ramos Farias, M.S.; Fazzi, L.; Romero, M.; Reynaga, E.; Marone, R.; Pando, M.A. High frequency of illegal drug use influences condom use among female transgender sex workers in Argentina: Impact on HIV and syphilis infections. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 2059–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, C.T.; Pando, M.A.; Reynaga, E.; Marone, R.; Sateren, W.B.; Montano, S.M.; Sanchez, J.L.; Avila, M.M. Sexual practices, drug use behaviors, and prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HTLV-1/2 in immigrant and non-immigrant female sex workers in Argentina. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2009, 11, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Ramos Farias, M.S.; Garcia, M.N.; Reynaga, E.; Romero, M.; Vaulet, M.L.; Fermepin, M.R.; Toscano, M.F.; Rey, J.; Marone, R.; Squiquera, L.; et al. First report on sexually transmitted infections among trans (male to female transvestites, transsexuals, or transgender) and male sex workers in Argentina: High HIV, HPV, HBV, and syphilis prevalence. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, e635–e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Ramos Farias, M.S.; Picconi, M.A.; Garcia, M.N.; Gonzalez, J.V.; Basiletti, J.; Pando Mde, L.; Avila, M.M. Human papilloma virus genotype diversity of anal infection among trans (male to female transvestites, transsexuals or transgender) sex workers in Argentina. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 51, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.; Silberman, M.; Martinez, S.; Sanguinetti, C. Healthcare progrAm. for sex workers: A public health priority. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2015, 30, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pando, M.A.; Coloccini, R.S.; Reynaga, E.; Rodriguez Fermepin, M.; Gallo Vaulet, L.; Kochel, T.J.; Montano, S.M.; Avila, M.M. Violence as a barrier for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Argentina. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, L. Sex work and the official neglect of occupational health and safety: The Queensland experience. Soc. Altern. 1999, 18, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.Y.; Donovan, B.; Harcourt, C.; Morton, A.; Moss, L.; Wallis, S.; Cook, K.; Batras, D.; Groves, J.; Tabrizi, S.N.; et al. Estimating the number of unlicensed brothels operating in Melbourne. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.P.; Fehler, G.; Chen, M.Y.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Denham, I.; Law, M.G.; Fairley, C.K. Testing commercial sex workers for sexually transmitted infections in Victoria, Australia: An evaluation of the impact of reducing the frequency of testing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.; McCormack, L.; Thng, C.; Wand, H.; McNulty, A. Cross-sectional survey of Chinese-speaking and Thai-speaking female sex workers in Sydney, Australia: Factors associated with consistent condom use. Sex. Health 2018, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, J.; Newton, D.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Hocking, J.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Fairley, C.K. Sex workers working within a legalised industry: Their side of the story. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2008, 84, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.M.; Binger, A.; Hocking, J.; Fairley, C.K. The incidence of sexually transmitted infections among frequently screened sex workers in a decriminalised and regulated system in Melbourne. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2005, 81, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, B.; Bi, P.; Waddell, R.; Chow, E.P.; Donovan, B.; McNulty, A.; Fehler, G.; Loff, B.; Shahkhan, H.; Fairley, C.K. Was an epidemic of gonorrhoea among heterosexuals attending an Adelaide sexual health services associated with variations in sex work policing policy? Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016, 92, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichiello, V.; Marino, R.; Browne, J.; Jamieson, M.; Peterson, K.; Reuter, B.; Robinson, K. Commercial sex between men: A prospective diary-based study. J. Sex Res. 2000, 37, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichiello, V.; Marino, R.; Browne, J.; Jamieson, M.; Peterson, K.; Reuter, B.; Robinson, K. Male sex workers in three Australian cities: Socio-demographic and sex work characteristics. J. Homosex 2001, 42, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichiello, V.; Marino, R.; Khan, M.A.; Browne, J. Alcohol and drug use in Australian male sex workers: Its relationship to the safety outcome of the sex encounter. AIDS Care 2003, 15, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.C.; Berry, G.; Rohrsheim, R.; Donovan, B. Sexual health and use of condoms among local and international sex workers in Sydney. Genitourin Med. 1996, 72, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Read, P.J.; Wand, H.; Guy, R.; Donovan, B.; McNulty, A.M. Unprotected fellatio between female sex workers and their clients in Sydney, Australia. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2012, 88, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaranayake, A.; Chen, M.; Hocking, J.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Cumming, R.; Fairley, C.K. Legislation requiring monthly testing of sex workers with low rates of sexually transmitted infections restricts access to services for higher-risk individuals. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2009, 85, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seib, C.; Fischer, J.; Najman, J.M. The health of female sex workers from three industry sectors in Queensland, Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seib, C.; Debattista, J.; Fischer, J.; Dunne, M.; Najman, J.M. Sexually transmissible infections among sex workers and their clients: Variation in prevalence between sectors of the industry. Sex. Health 2009, 6, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvey, L.A.; Hallett, J.; McCausland, K.; Bates, J.; Donovan, B.; Lobo, R. Declining condom use among sex workers in Western Australia. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvey, L.A.; Lobo, R.C.; McCausland, K.L.; Donovan, B.; Bates, J.; Hallett, J. Challenges facing asian sex workers in Western Australia: Implications for health promotion and support services. Front Public Health 2018, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Hocking, J.S.; Fehler, G.; Williams, H.; Chen, M.Y.; Fairley, C.K. The prevalence of sexually transmissible infections among female sex workers from countries with low and high prevalences in Melbourne. Sex. Health 2013, 10, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, C.; Ouellet, N.; Jansson, M. Unmet health care needs among sex workers in five census metropolitan areas of Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e266–e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.L.; Callon, C.; Li, K.; Wood, E.; Kerr, T. Offer of financial incentives for unprotected sex in the context of sex work. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010, 29, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K.; Bright, V.; Gibson, K.; Tyndall, M.W.; Maka Project, P. Sexual and drug-related vulnerabilities for HIV infection among women engaged in survival sex work in Vancouver, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2007, 98, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K.; Strathdee, S.A.; Shoveller, J.; Rusch, M.; Kerr, T.; Tyndall, M.W. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: Implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, A.E.; Craib, K.J.P.; Chan, K.; Martindale, S.; Miller, M.L.; Schechter, M.T.; Hogg, R.S. Sex trade involvement and rates of human immunodeficiency virus positivity among young gay and bisexual men. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.K.; Ho, K.M.; Lo, K.K. A behaviour sentinel surveillance for female sex workers in the Social Hygiene Service in Hong Kong (1999–2000). Int. J. STD AIDS 2002, 13, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.S.; Mak, W.W. Contextual influences on safer sex negotiation among female sex workers (FSWs) in Hong Kong: The role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), FSWs’ managers, and clients. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.T.; Tsui, H.Y.; Ho, S.P.; Wong, E.; Yang, X. Prevalence of psychological problems and relationships with condom use and HIV prevention behaviors among Chinese female sex workers in Hong Kong. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.M.; Yeoh, G.P.; Cheung, H.N.; Fong, F.Y.; Chan, K.W. Prevalence of abnormal papanicolaou smears in female sex workers in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med. 2013, 19, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ling, D.C.; Holroyd, E.A.; Wong, W.C.W.; Gray, A. Handling emerging health needs among a migrant population-factors associated with suicide attempts and suicide ideation among female street sex workers in Hong Kong. Clin. Eff. Nurs. 2004, 8, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.T.; Lee, K.C.; Chan, D.P. Community-based sexually transmitted infection screening and increased detection of pharyngeal and urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in female sex workers in Hong Kong. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2015, 42, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wong, W.C.; Holroyd, E.A.; Gray, A.; Ling, D.C. Female street sex workers in Hong Kong: Moving beyond sexual health. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006, 15, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, E.A.; Wong, W.C.; Ann Gray, S.; Ling, D.C. Environmental health and safety of Chinese sex workers: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, A.; Andalo, F.; Carla, E.M.; Tommaso, S.D. Prevalence of STDs and HIV infection among immigrant sex workers attending an STD centre in Bologna, Italy. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2001, 77, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nigro, L.; Larocca, L.; Celesia, B.M.; Montineri, A.; Sjoberg, J.; Caltabiano, E.; Fatuzzo, F.; Unit Operators, G. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases among Colombian and Dominican female sex workers living in Catania, Eastern Sicily. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2006, 8, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, M.; Mancuso, S.; Sinicco, A.; Vaccher, E.; Traina, C.; Di Fabrizio, N.; De Lalla, F.; Tirelli, U. Human immunodeficiency virus seroprevalence and condom use among female sex workers in Italy. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1998, 25, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trani, F.; Altomare, C.; Nobile, C.G.; Angelillo, I.F. Female sex street workers and sexually transmitted infections: Their knowledge and behaviour in Italy. J. Infect. 2006, 52, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishi, K.; Suzuki, F.; Saito, A.; Kubota, T. Prevalence of human papillomavirus, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in commercial sex workers in Japan. Infect. Dis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 8, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishi, K.; Suzuki, F.; Saito, A.; Kubota, T. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection and its correlation with cervical lesions in commercial-sex workers in Japan. J. Obstet Gynaecol. Res. 2000, 26, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishi, K.; Suzuku, F.; Saito, A.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kubota, T. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus antibodies and hepatitis B antigen among commercial sex workers in Japan. Infect. Dis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001, 9, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, H.; Sakumoto, M.; Takahashi, K.; Nagafuji, T.; Akazawa, K.; Kumazawa, J. Reduced chlamydial infection and gonorrhea among commercial sex workers in Fukuoka City, Japan. Int. J. Urol. 1998, 5, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsunoe, H.; Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, H.; Sano, M.; Nakamura, G.; Shin, T.; Kanayama, A.; Kobayashi, I.; Mochida, O.; Kumazawa, J.; et al. High prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalium in female commercial sex workers in Japan. Int. J. STD AIDS 2000, 11, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, R.B.T.; Cheung, O.N.Y.; Bee Choo, T.; Chen, M.I.C.; Chan, R.K.W.; Mee Lian, W. Efficacy of multicomponent culturally tailored HIV/STI prevention interventions targeting foreign female entertainment workers: A quasi-experimental trial. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2018, 94, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.L.; Chan, R.; Koh, D. Long-term effects of condom promotion programmes for vaginal and oral sex on sexually transmitted infections among sex workers in Singapore. AIDS 2004, 18, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.; Chan, R.K. A prospective study of pharyngeal gonorrhoea and inconsistent condom use for oral sex among female brothel-based sex workers in Singapore. Int. J. STD AIDS 1999, 10, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.L.; Chan, R.K.; Koh, D.; Wee, S. Factors associated with condom use for oral sex among female brothel-based sex workers in Singapore. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2000, 27, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belza, M.J. Risk of HIV infection among male sex workers in Spain. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2005, 81, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratos, M.A.; Eiros, J.M.; Orduna, A.; Cuervo, M.; Ortiz de Lejarazu, R.; Almaraz, A.; Martin-Rodriguez, J.F.; Gutierrez-Rodriguez, M.P.; Orduna Prieto, E.; Rodriguez-Torres, A. Influence of syphilis in hepatitis B transmission in a cohort of female prostitutes. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1993, 20, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Amo, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Belda, J.; Fernandez, E.; Martinez, R.; Gomez, I.; Torres, M.; Saiz, A.G.; Ortiz, M. Prevalence and risk factors of high-risk human papillomavirus in female sex workers in Spain: Differences by geographical origin. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009, 18, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanjose, S.; Marshall, V.; Sola, J.; Palacio, V.; Almirall, R.; Goedert, J.J.; Bosch, F.X.; Whitby, D. Prevalence of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in sex workers and women from the general population in Spain. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, C.; Esteve, A.; Sanclemente, C.; Martro, E.; Lugo, R.; Molinos, S.; Gonzalez, V.; Ausina, V.; Casabona, J. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections among immigrant female sex workers in Catalonia, Spain. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2008, 35, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Torres, M.; Canals, J.; Fernandez, E.; Belda, J.; Ortiz, M.; Del Amo, J. Higher incidence and persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in female sex workers compared with women attending family planning. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, e688–e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, J.A.; Aguado, I.; Rivero, A.; Vergara, A.; Hernandez-Quero, J.; Luque, F.; Pino, R.; Abad, M.A.; Santos, J.; Cruz, E.; et al. HIV-1 infection among non-intravenous drug user female prostitutes in Spain. No evidence of evolution to pattern II. AIDS 1992, 6, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinedo González, R.; Palacios Picos, A.; de la Iglesia Gutiérrez, M. “Surviving the violence, humiliation, and loneliness means getting high”: Violence, loneliness, and health of female sex workers. J. Interpers Violence 2018, 9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Cerdeira, C.; Sanchez-Blanco, E.; Gutierrez, A.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, A.; Sanchez-Blanco, B. Knowledge of HIV and HPV infection, and acceptance of HPV vaccination in spanish female sex worker. Open Dermatol J. 2014, 8, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.E.; Boon, B.J.; Garretsen, H.F.; van de Mheen, D. Vaccination uptake and awareness of a free hepatitis B vaccination progrAm. among female commercial sex workers. Womens Health Issues 2009, 19, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennema, J.S.; van Ameijden, E.J.; Coutinho, R.A.; van den Hoek, A.A. HIV, sexually transmitted diseases and gynaecologic disorders in women: Increased risk for genital herpes and warts among HIV-infected prostitutes in Amsterdam. AIDS 1995, 9, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennema, J.S.; van Ameijden, E.J.; Coutinho, R.A.; van den Hoek, J.A. Validity of self-reported sexually transmitted diseases in a cohort of drug-using prostitutes in Amsterdam: Trends from 1986 to 1992. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1995, 24, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E.J. Sex work and mental health: A study of women in the Netherlands. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, E.; Kroone, N.; Freriks, E.; van Dam, C.L.; Alberts, C.J.; Hogewoning, A.A.; Bruisten, S.; van Dijk, A.; Kroone, M.M.; Waterboer, T.; et al. Vaginal and anal human papillomavirus infection and seropositivity among female sex workers in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Prevalence, concordance and risk factors. J. Infect. 2018, 76, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haastrecht, H.J.; Fennema, J.S.; Coutinho, R.A.; van der Helm, T.C.; Kint, J.A.; van den Hoek, J.A. HIV prevalence and risk behaviour among prostitutes and clients in Amsterdam: Migrants at increased risk for HIV infection. Genitourin Med. 1993, 69, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, M.G.; Gotz, H.M.; van Leeuwen, P.A.; Prins, M.; van de Laar, M.J.W. HIV and sexual risk behavior among commercial sex workers in the Netherlands. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verscheijden, M.M.A.; Woestenberg, P.J.; Gotz, H.M.; van Veen, M.G.; Koedijk, F.D.H.; van Benthem, B.H.B. Sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers tested at STI clinics in the Netherlands, 2006–2013. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2015, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Guzman, R.; Harris, S.G. Sex trade in a male-to-female transgender population: Psychosocial correlates of inconsistent condom use. Sex. Health 2008, 5, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, D.L.; Kim, A.; Ruiz, J.; Morrow, S.; Reardon, J.; Lynch, M.; Klausner, J.D.; Molitor, F.; Allen, B.; Ajufo, B.G.; et al. Health indicators among low income women who report a history of sex work: The population based Northern California Young Women’s Survey. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2005, 81, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Irwin, K.L.; Inciardi, J.; Bowser, B.; Schilling, R.; Word, C.; Evans, P.; Faruque, S.; McCoy, H.V.; Edlin, B.R. The high-risk sexual practices of crack-smoking sex workers recruited from the streets of three American cities. The Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1998, 25, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, E.V.; Simon, P.M.; Osofsky, H.J.; Balson, P.M.; Gaumer, H.R. The male street prostitute: A vector for transmission of HIV infection into the heterosexual world. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, L.; Darrow, W.; Witte, J.; Cohen, J.; French, J.; Gill, P.S.; Potterat, J.; Sikes, K.; Reich, R.; Hadler, S. Sexual practices in the transmission of hepatitis B virus and prevalence of hepatitis delta virus infection in female prostitutes in the United States. JAMA 1992, 267, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surratt, H.L.; O’Grady, C.; Kurtz, S.P.; Levi-Minzi, M.A.; Chen, M. Outcomes of a behavioral intervention to reduce HIV risk among drug-involved female sex workers. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera, R.J.; Sawyer, R.G.; Schiraldi, G.R. Perceived health needs of inner-city street prostitutes: A preliminary study. Am. J. Health Behav. 2001, 25, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- el-Bassel, N.; Schilling, R.F.; Irwin, K.L.; Faruque, S.; Gilbert, L.; Von Bargen, J.; Serrano, Y.; Edlin, B.R. Sex trading and psychological distress among women recruited from the streets of Harlem. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grath-Lone, L.M.; Marsh, K.; Hughes, G.; Ward, H. The sexual health of female sex workers compared with other women in England: Analysis of cross-sectional data from genitourinary medicine clinics. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2014, 90, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grath-Lone, L.M.; Marsh, K.; Hughes, G.; Ward, H. The sexual health of male sex workers in England: Analysis of cross-sectional data from genitourinary medicine clinics. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2014, 90, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, G. Sex workers’ utilisation of health services in a decriminalised environment. N. Z. Med. J. 2014, 127, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Plumridge, L.; Abel, G. Services and information utilised by female sex workers for sexual and physical safety. N. Z. Med. J. 2000, 113, 370–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.; Gama, A.; Fuertes, R.; Mendao, L.; Barros, H. Risk-taking behaviours and HIV infection among sex workers in Portugal: Results from a cross-sectional survey. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2015, 91, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Goncalves, I.; Borges, I.; Filho, J.; Cerqueira, N.; Saraiva, M.E. Male sex workers in Lisbon, Portugal: A pilot study of demographics, sexual behavior, and HIV prevalence. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 2014, 5, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeganey, N.; Barnard, M.; Leyland, A.; Coote, I.; Follet, E. Female streetworking prostitution and HIV infection in Glasgow. BMJ 1992, 305, 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plant, M.L.; Plant, M.A.; Thomas, R.M. Alcohol, AIDS risks and commercial sex: Some preliminary results from a Scottish study. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 1990, 25, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, R.P.; Van Renterghem, L.; Traen, A. Chlamydia trachomatis in female sex workers in Belgium: 1998–2003. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2005, 81, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Prieto, J.B.; Avila, V.S.; Folch, C.; Montoliu, A.; Casabona, J. Linked factors to access to sexual health checkups of female sex workers in the metropolitan region of Chile. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 27, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resl, V.; Kumpova, M.; Cerna, L.; Novak, M.; Pazdiora, P. Prevalence of STDs among prostitutes in Czech border areas with Germany in 1997-2001 assessed in project “Jana”. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2003, 79, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, S.K.; Svare, E.I.; Worm, A.M.; Walboomers, J.M.; Meijer, C.J.; van den Brule, A.J. Human papillomavirus infection in Danish female sex workers. Decreasing prevalence with age despite continuously high sexual activity. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2000, 27, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uuskula, A.; Fischer, K.; Raudne, R.; Kilgi, H.; Krylov, R.; Salminen, M.; Brummer-Korvenkontio, H.; St Lawrence, J.; Aral, S. A study on HIV and hepatitis C virus among commercial sex workers in Tallinn. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2008, 84, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, L.; Simon, K.; Sarosi, P. Drug use among sex workers in Hungary. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 93, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakre, S.; Arteaga, G.; Nunez, A.E.; Bautista, C.T.; Bolen, A.; Villarroel, M.; Peel, S.A.; Paz-Bailey, G.; Scott, P.T.; Pascale, J.M.; et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and factors associated with syphilis among female sex workers in Panama. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2013, 89, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegria, M.; Vera, M.; Freeman, D.H., Jr.; Robles, R.; Santos, M.C.; Rivera, C.L. HIV infection, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms among Puerto Rican sex workers. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 2000–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Jung, S.Y.; Kwon, D.S.; Jung, M.; Park, B.J. Condom use and prevalence of genital chlamydia trachomatis among the Korean female sex workers. Epidemiol. Health 2010, 32, e2010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossler, W.; Koch, U.; Lauber, C.; Hass, A.K.; Altwegg, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Landolt, K. The mental health of female sex workers. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 122, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interactions for Gender Justice. Map of Sex Work Law. Available online: http://spl.ids.ac.uk/sexworklaw/countries (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Hedt, B.L.; Pagano, M. Health indicators: Eliminating bias from convenience sampling estimators. Stats Med. 2011, 30, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripepi, G.; Jager, K.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2010, 115, c94–c99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmier, J.K.; Halpern, M.T. Patient recall and recall bias of health state and health status. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2004, 4, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.G.; Sabin, K. Sampling hard-to-reach populations with respondent driven sampling. Method Innov. 2010, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroter, S.; Plowman, R.; Hutchings, A.; Gonzalez, A. Reporting ethics committee approval and patient consent by study design in five general medical journals. J. Med. Ethics 2006, 32, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, E.D.; Weiser, S.D.; Sorensen, J.L.; Dilworth, S.; Cohen, J.; Neilands, T.B. Housing patterns and correlates of homelessness differ by gender among individuals using San Francisco free food programs. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weiser, S.D.; Neilands, T.B.; Comfort, M.L.; Dilworth, S.E.; Cohen, J.; Tulsky, J.P.; Riley, E.D. Gender-specific correlates of incarceration among marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.; Jakobsson, P. Sweden’s abolitionist discourse and law: Effects on the dynamics of Swedish sex work and on the lives of Sweden’s sex workers. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2014, 14, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolajärvi, N.; Vuolajärvi, N. Governing in the Name of Caring—The Nordic Model of Prostitution and its Punitive Consequences for Migrants Who Sell Sex. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2019, 16, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurth, M.H.; Schleifer, R.; McLemore, M.; Todrys, K.W.; Amon, J.J. Condoms as evidence of prostitution in the United States and the criminalization of sex work. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Shannon, K.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.; Chettiar, J.; Goldenberg, S.; Krüsi, A. Condoms and sexual health education as evidence: Impact of criminalization of in-call venues and managers on migrant sex workers access to HIV/STI prevention in a Canadian setting. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, J.; Berg, R. Sex workers as safe sex advocates: Sex workers protect both themselves and the wider community from HIV. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2014, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wolock, T.M.; Carter, A.; Nguyen, G.; Kyu, H.H.; Gakidou, E.; Hay, S.I.; Mills, E.J.; Trickey, A.; Msemburi, W.; et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2015: The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet HIV 2016, 3, e361–e387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, R.; McCausland, K.; Bates, J.; Hallett, J.; Donovan, B.; Selvey, L.A. Sex workers as peer researchers—A qualitative investigation of the benefits and challenges. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, E.; Fawkes, J.; Stardust, Z. Mandatory testing for HIV and sexually transmissible infections among sex workers in Australia: A barrier to HIV and STI prevention. World J. AIDS 2012, 2, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krüsi, A.; Kerr, T.; Taylor, C.; Rhodes, T.; Shannon, K. ‘They won’t change it back in their heads that we’re trash’: The intersection of sex work-related stigma and evolving policing strategies. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Subject Headings/MESH Terms | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Sex work Sex workers Developed countries |

|

| ProQuest | ||

| Scopus | ||

| Current Contents Connect | ||

| Medline | Sex work Sex workers Developed countries | |

| Embase | Sex worker Prostitution Developed country | |

| PsycINFO | Prostitution Developed countries | |

| Global Health | Sex workers Prostitutes Prostitution Developed countries |

| Legal Status | Location of Included Studies (n) |

|---|---|

| Criminalized | Puerto Rico (n = 1); South Korea (n = 1); USA (n = 8) |

| Partial criminalization | Argentina (n = 6); Australia, WA (n = 3); Australia, QLD (prior to 1999) (n = 1); Australia, SA (n = 1); Belgium (n = 1); Canada (prior to 2014) (n = 4); Denmark (n = 1); England (n = 2); Estonia (n = 1); Hong Kong (n = 8); Italy (n = 4); Japan (n = 5); Netherlands (prior to 2000) (n = 3); New Zealand (prior to 2003) (n = 1); Portugal (n = 2); Scotland (n = 2); Singapore (n = 4); Spain (n = 9) |

| Nordic | Canada (from 2014) (n = 1) |

| Legal | Australia, QLD (from 1999) (n = 5); Australia, VIC (n = 11); Chile (n = 1); Czech Republic (n = 1); Hungary (n = 1); Netherlands (from 2000) (n = 5); Panama (n = 1); Switzerland (n = 1) |

| Decriminalization | Australia, NSW (n = 9); New Zealand (from 2003) (n = 1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCann, J.; Crawford, G.; Hallett, J. Sex Worker Health Outcomes in High-Income Countries of Varied Regulatory Environments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083956

McCann J, Crawford G, Hallett J. Sex Worker Health Outcomes in High-Income Countries of Varied Regulatory Environments: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083956

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCann, Jessica, Gemma Crawford, and Jonathan Hallett. 2021. "Sex Worker Health Outcomes in High-Income Countries of Varied Regulatory Environments: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083956

APA StyleMcCann, J., Crawford, G., & Hallett, J. (2021). Sex Worker Health Outcomes in High-Income Countries of Varied Regulatory Environments: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083956