Neuroenhancement in French and Romanian University Students, Motivations and Associated Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.2.2. University Curriculum

2.2.3. Stress Evaluation

2.2.4. Assessment of Substance Use for Neuroenhancement

2.2.5. Other Assessment of Substance Use

2.3. Patient and Public Involvement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Neuroenhancement

3.3. Factors Associated with Neuroenhancement

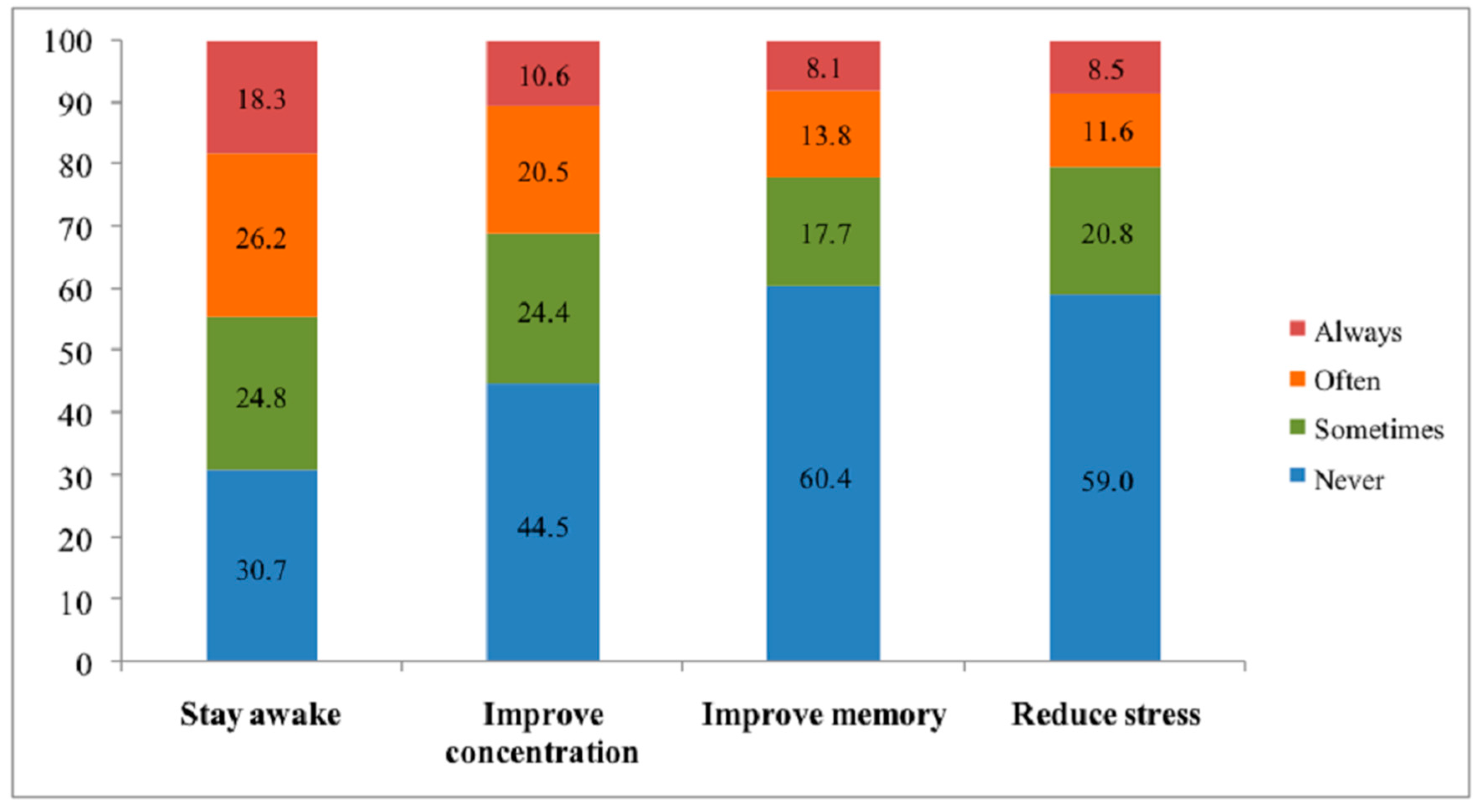

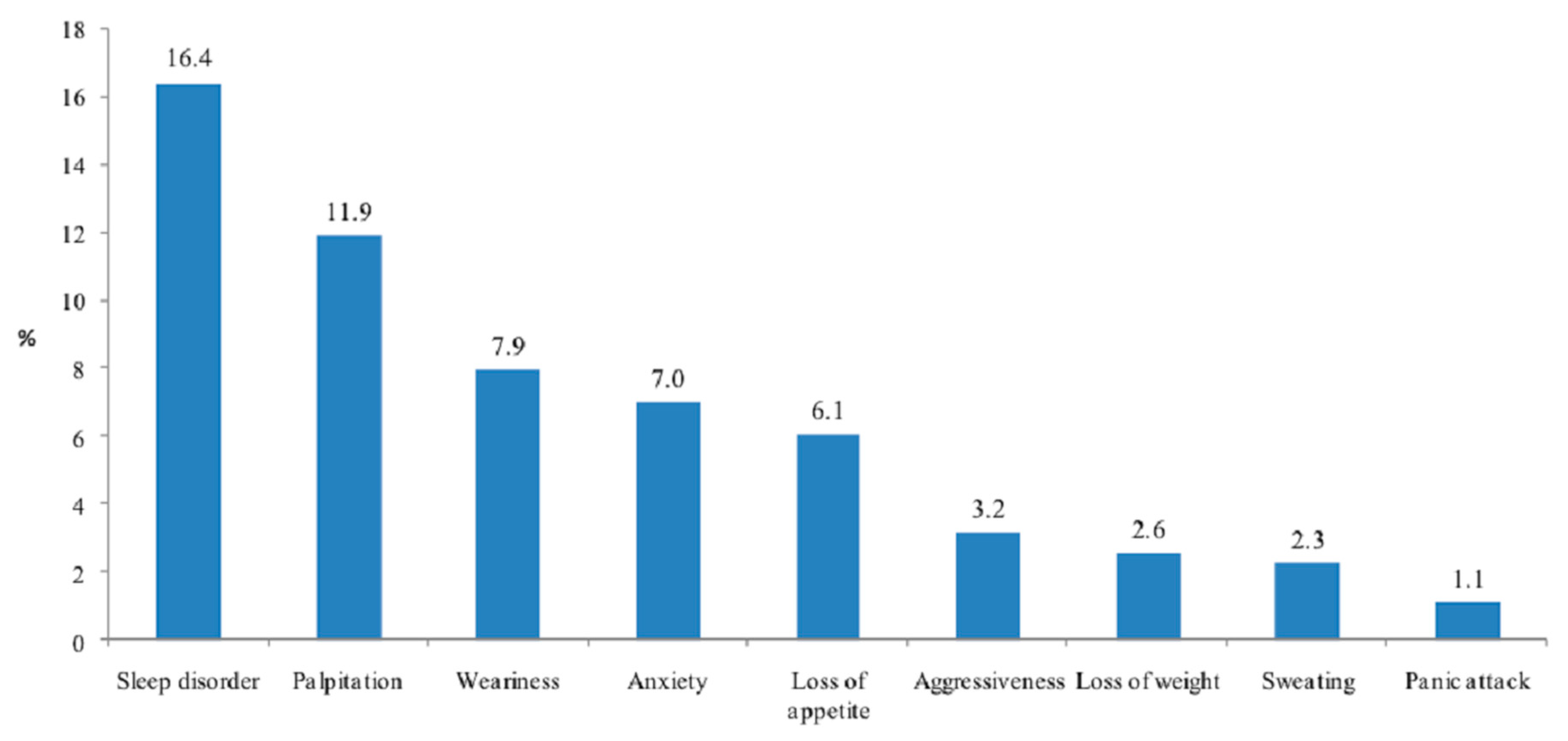

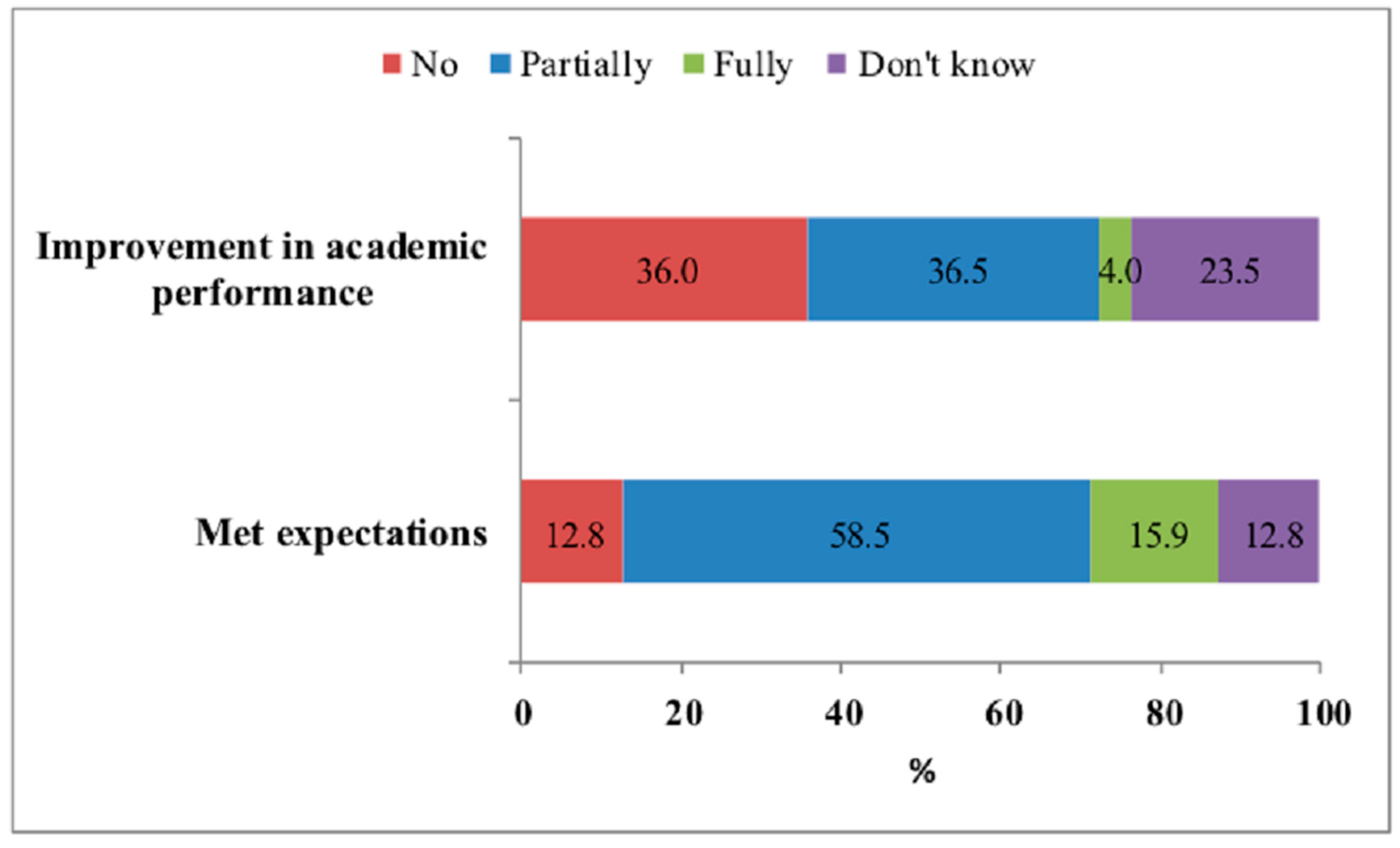

3.4. Reasons for Neuroenhancement, Side Effects and Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Repantis, D.; Schlattmann, P.; Laisney, O.; Heuser, I. Modafinil and methylphenidate for neuroenhancement in healthy individuals: A systematic review. Pharm. Res. 2010, 62, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pighi, M.; Pontoni, G.; Sinisi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Mattei, G.; Pingani, L.; Simoni, E.; Galeazzi, G.M. Use and propensity to use substances as cognitive enhancers in Italian medical students. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, L.J.; Schaub, M.P. The use of prescription drugs and drugs of abuse for neuroenhancement in Europe: Not widespread but a reality. Eur. Psychol. 2015, 20, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, L.J.; Liechti, M.E.; Herzig, F.; Schaub, M.P. To dope or not to dope: Neuroenhancement with prescription drugs and drugs of abuse among Swiss University students. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, D.L.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Costello, E.J.; Hoyle, R.H.; McCabe, S.E.; Swartzwelder, H.S. Motives and perceived consequences of nonmedical ADHD medication use by college students: Are students treating themselves for attention problems? J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaez, M.; Ponce de Leon, A.; Laflamme, L. Health-related determinants of perceived quality of life: A comparison between first-year university students and their working peers. Work Read Mass. 2006, 26, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hildt, E.; Lieb, K.; Bagusat, C.; Franke, A.G. Reflections on addiction in students using stimulants for neuroenhancement: A preliminary interview study. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimsrud, M.M.; Brekke, M.; Syse, V.L.; Vallersnes, O.M. Acute Poisoning Related to the Recreational Use of Prescription Drugs: An Observational Study from Oslo, Norway. BMC Emerg. Med. 2019, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorff, E.; Poskowsky, J.; Isserstedt, W. [Forms of stress compensation and performance enhancement in students]; HIS: Hannover, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fond, G.; Gavaret, M.; Llorca, P.; Boyer, L.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.; Domenech, P. (Mis)use of prescribed stimulants in the medical student community: Motives and behaviors. A population-based cross-sectional study. Eur. Neuropsychopharm. 2016, 26, S348–S349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Franke, A.G.; Bonertz, C.; Christmann, M.; Huss, M.; Fellgiebel, A.; Hildt, E.; Lieb, K. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants and illicit use of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in pupils and students in Germany. Pharmacopsychiatry 2011, 44, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; MacGregor, A.; Fond, G. A preliminary study on cognitive enhancer consumption behaviors and motives of French Medicine and Pharmacology students. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 18, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, S.; Rehm, J.; Patra, J.; Zatonski, W. Comparing alcohol consumption in central and eastern Europe to other European countries. Alcohol Alcohol 2007, 42, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibell, B.; Andersson, B.; Bjarnason, T.; Ahlström, S.; Balakireva, O. The ESPAD Report 2003: Alcohol and other Drug Use Among Students in 35 European Countries; The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN) and the Pompidou Group at the Council of Europe: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Botella, J.; Sepúlveda, A.R.; Huang, H.; Gambara, H. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of the SCOFF. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, E92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.D.; Grigioni, S.; Chelali, S.; Meyrignac, G.; Thibaut, F.; Dechelotte, P. Validation of the French version of SCOFF questionnaire for screening of eating disorders among adults. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumboiu, M.I.; Cazacu, I.; Zunquin, G.; Manole, F.; Mogosan, C.I.; Porrovecchio, A.; Peze, T.; Tavolacci, M.-P.; Ladner, J. Nutritional status and eating disorders among medical students from the Cluj-Napoca University centre. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2018, 91, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riou Franca, L.; Dautzenberg, B.; Falissard, B.; Reynaud, M. Peer substance use overestimation among French university students: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, T.S.; Brewer, R.D.; Mokdad, A.; Denny, C.; Serdula, M.K.; Marks, J.S. Binge drinking among US adults. J. Am. Med Assoc. 2003, 289, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolacci, M.-P.; Boerg, E.; Richard, L.; Meyrignac, G.; Dechelotte, P.; Ladner, J. Prevalence of binge drinking and associated behaviours among 3286 college students in France. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.R.; Giles, G.E.; Marriott, B.P.; Judelson, D.A.; Glickman, E.L.; Geiselman, P.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Intake of caffeine from all sources and reasons for use by college students. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2019, 38, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.L.; Betancourt, J.; Pagán, I.; Fabián, C.; Cruz, S.Y.; González, A.M.; González, M.J.; Rivera-Soto, W.T.; Palacios, C. Caffeinated-beverage consumption and its association with socio-demographic characteristics and self-perceived academic stress in first and second year students at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus (UPR-MSC). P R Health Sci. J. 2013, 32, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. Caffeinated beverages and energy drink: Pattern, awareness and health side effects among Omani university students. Biomed. Res. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, J.; Jensen, C.; Dunn, M.; Chan, G.; Forlini, C.; Kaye, S.; Partridge, B.; Farrell, M.; Racine, E.; Hall, W. Non-medical prescription stimulant use to improve academic performance among Australian university students: Prevalence and correlates of use. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quednow, B.B. Ethics of neuroenhancement: A phantom debate. BioSocieties 2010, 5, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, H.; Schmidt, S.; Dirhold, T.; Nosch, S. The effects of a caffeine placebo and suggestion on blood pressure, heart rate, well-being and cognitive performance. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2002, 43, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, S.A.; Gueorguieva, R.V.; Pittman, B.; Rosen, R.R.; Aslanzadeh, F.; Tennen, H.; Leen, S.; Hawkins, K.; Raskin, S.; Wood, R.M.; et al. Longitudinal influence of alcohol and marijuana use on academic performance in college students. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B. Poll results: Look who’s doping. Nature 2008, 452, 674–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Heuzey, M.-F. La prescription actuelle du méthylphénidate (Ritaline®). Neuropsychiatr. Enfance. Adolesc. 2009, 57, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickenhorst, P.; Vitzthum, K.; Klapp, B.F.; Groneberg, D.; Mache, S. Neuroenhancement among German University students: Motives, expectations, and relationship with psychoactive lifestyle drugs. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2012, 44, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland-Benhaïm, C.; Pélissier-Alicot, A.-L.; Léonetti, G. Non-respect des règles de dispensation des médicaments et responsabilité du pharmacien d’officine. Médecine 2011, 2011, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quednow, B.B. Neurophysiologie des Neuro-Enhancements: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen. Suchtmagazin 2010, 36, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieva, I.; Boland, J.; Farah, M.J. Objective and subjective cognitive enhancing effects of mixed amphetamine salts in healthy people. Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Farah, M.J. Are prescription stimulants “smart pills”? The epidemiology and cognitive neuroscience of prescription stimulant use by normal healthy individuals. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilens, T.E.; Adler, L.A.; Adams, J.; Sgambati, S.; Rotrosen, J.; Sawtelle, R.; Utzinger, L.; Fusillo, S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: A systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, A.D.; Webb, E.M.; Noar, S.M. Illicit use of prescription ADHD medications on a college campus: A multimethodological approach. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 57, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.E.; Knight, J.R.; Teter, C.J.; Wechsler, H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction 2005, 100, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romo, L.; Ladner, J.; Kotbagi, G.; Morvan, Y.; Saleh, D.; Tavolacci, M.P. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and addictions (substance and behavioral): Prevalence and characteristics in a multicenter study in France. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmer, J.R.; Fossos-Wong, N.; Geisner, I.M.; Yeh, J.-C.; Larimer, M.E.; Cimini, M.D.; Vincent, K.B.; Allen, H.K.; Barrall, A.L.; Arria, A.M. Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants as a “Red Flag” for other substance use. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Murray, S.B.; Nagata, J.M. Associations between eating disorders and illicit drug use among college students. Int. J. Eat Disord. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schelle, K.J.; Olthof, B.M.J.; Reintjes, W.; Bundt, C.; Gusman-Vermeer, J.; Van Mil, A.C.C.M. A survey of substance use for cognitive enhancement by university students in the Netherlands. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, A.D.; Smith, P.J. Aided by Adderall: Illicit use of ADHD medications by college students. J. Natl. Coll. Honor. Counc. 2017, 18, 41–77. [Google Scholar]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Janusis, G.; Wilson, K.G.; Verdi, G.; Paquin, G.; Lopes, J.; Varejao, M.; Dussault, C. Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among a sample of college students: Relationship with psychological variables. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, B.A.; Weyandt, L.L.; Marraccini, M.E.; Oster, D.R. The relationship between nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, executive functioning and academic outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommaerts, J.-L.; Beerens, G.; Block, L.V.D.; Soetens, E.; Schol, S.; Van De Vijver, E.; Devroey, D. Influence of methylphenidate treatment assumptions on cognitive function in healthy young adults in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2013, 6, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, A.; Hermann, C. Placebo- and nocebo-effects in cognitive neuroenhancement: When expectation shapes perception. Front. Psychiatry. 2019, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroutil, L.A.; Van Brunt, D.L.; Herman-Stahl, M.A.; Heller, D.C.; Bray, R.M.; Penne, M.A. Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006, 84, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Swanson, J.M. The action of enhancers can lead to addiction. Nature 2008, 451, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragan, C.I.; Bard, I.; Singh, I. What should we do about student use of cognitive enhancers? An analysis of current evidence. Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greely, H.; Sahakian, B.; Harris, J.; Kessler, R.C.; Gazzaniga, M.; Campbell, P.; Farah, M.J. Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature 2008, 456, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlini, C.; Hall, W. The is and ought of the ethics of neuroenhancement: Mind the gap. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cluj-Napoca (n = 218) | Rouen (n = 534) | Opal Coast University (n = 358) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female: n (%) | 180 (82.5) | 386 (72.3) | 248 (70.7) |

| Mean age (SD) | 21.4 (1.8) | 20.1 (1.9) | 19.7 (1.7) |

| Curriculum n (%) | |||

| Mixed university group | 0 (0.0) | 326 (61.1) | 78 (21.8) |

| Healthcare | 218 (100) | 208 (38.9) | 280 (78.2) |

| Academic year of study n (%) | |||

| 1 | 37 (17.0) | 231 (43.3) | 259 (73.6) |

| 2 | 70 (32.1) | 75 (14.0) | 54 (15.3) |

| 3 | 26 (11.9) | 110 (20.6) | 24 (6.8) |

| >3 | 85 (39.0) | 118 (22.1) | 15 (4.3) |

| Cluj-Napoca (n = 218) | Rouen (n = 534) | Opal Coast University (n = 358) | Total (N = 1110) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription drugs * (%) | 6.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.2 |

| Beta-blockers | 6.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| Methylphenidate | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Modafinil | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Drugs of abuse * (%) | 8.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| Alcohol | 5.6 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 4.0 |

| Cannabis | 2.3 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| Amphetamines | 2.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Cocaine | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Soft enhancers ** (%) | 84.9 | 55.4 | 36.3 | 55.0 |

| Coffee | 80.7 | 43.4 | 25.9 | 45.3 |

| Vitamins | 53.2 | 23.7 | 15.3 | 26.9 |

| Energy drinks | 17.4 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 10.0 |

| Caffeine tablets | 8.2 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

| Prescription Drugs | Drugs of Abuse | Soft Enhancers | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 24) | No (n = 1086) | p-Value | Yes (n = 48) | No (n = 1062) | p-Value | Yes (n = 611) | No (n = 499) | p-Value | ||

| Male (%) | 65.2 | 74.0 | 0.34 | 58.3 | 74.5 | 0.01 | 76.0 | 71.0 | 0.06 | 73.8 |

| Mean age (SD *) | 21.9 (1.7) | 20.2 (1.9) | 0.89 | 21.0 (1.7) | 20.2 (1.9) | 0.64 | 20.5 (1.9) | 19.8 (1.7) | <0.001 | 20.2 (1.9) |

| Student job (%) | 16.7 | 13.3 | 0.63 | 22.9 | 12.9 | 0.05 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 0.64 | 13.4 |

| Study grant-holder (%) | 29.1 | 42.0 | 0.21 | 33.3 | 40.7 | 0.13 | 38.9 | 45.1 | 0.06 | 41.7 |

| Curriculum (%) | ||||||||||

| Mixed university group | 8.3 | 37.0 | 0.004 | 35.4 | 36.5 | 0.88 | 31.3 | 42.1 | <0.001 | 36.4 |

| Healthcare | 91.7 | 63.0 | 64.6 | 63.5 | 68.7 | 57.9 | 63.6 | |||

| Academic year of study (%) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 12.5 | 48.5 | 31.2 | 48.5 | 39.7 | 57.6 | 47.7 | |||

| 2 | 20.8 | 18.0 | <0.001 | 20.9 | 17.9 | 0.12 | 20.8 | 14.6 | <0.001 | 18.1 |

| 3 | 16.7 | 14.4 | 20.9 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 14.0 | 14.5 | |||

| >3 | 50.0 | 19.1 | 27.0 | 19.4 | 24.6 | 13.8 | 19.7 | |||

| Mean stress (SD *) | 20.6 (6.1) | 16.7 (7.4) | 0.43 | 19.7 (7.8) | 16.7 (7.3) | 0.85 | 17.6 (7.3) | 15.9 (7.5) | 0.96 | 16.8 (7.4) |

| Tobacco smoking (%) | 25.0 | 21.4 | 0.67 | 56.3 | 19.9 | <0.001 | 26.9 | 14.8 | <0.001 | 21.5 |

| Binge drinking (%) Never Occasional Frequent | 50.0 41.7 8.3 | 44.1 48.8 7.1 | 0.78 | 31.3 45.8 22.9 | 44.9 48.8 6.3 | <0.001 | 42.6 49.1 8.3 | 46.4 48.1 5.5 | 0.174 | 44.3 48.6 7.1 |

| Eating disorders (%) | 33.3 | 25.1 | 0.36 | 33.3 | 24.9 | 0.19 | 26.7 | 23.5 | 0.21 | 25.3 |

| KERRYPNX | Drugs of Abuse | Soft Enhancers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR 95% CI | p-Value | AOR 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Male | 2.23 (1.21–4.11) | 0.01 | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) | 0.42 |

| Student job | 2.42 (1.13–5.17) | 0.001 | ||

| Study grant-holder | 0.68 (0.35–1.33) | 0.27 | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | 0.90 |

| Curriculum | ||||

| Mixed university group | 1 (Ref) | |||

| Healthcare | 1.38 (1.01–1.87) | 0.04 | ||

| Academic year of study | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| 3 | 1.23 (0.51–2.96) | 0.64 | 1.22 (0.83–1.79) | 0.30 |

| >3 | 1.79 (0.74–4.32) | 0.19 | 0.93 (0.60–1.45) | 0.77 |

| 1.37 (0.58–3.24) | 0.46 | 0.90 (0.75–1.28) | 0.71 | |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Tobacco smoking | 5.50 (2.98–10.14) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.94–3.80) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Binge drinking | ||||

| Never | 1 (Ref) | - | 1 (Ref) | |

| Occasional | 1.55 (0.76–3.19) | 0.23 | 1.69 (1.26–5.92) | <0.001 |

| Frequent | 6.49 (2.53–16.60) | <0.001 | 3.34 (1.88–4.13) | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brumboiu, I.; Porrovecchio, A.; Peze, T.; Hurdiel, R.; Cazacu, I.; Mogosan, C.; Ladner, J.; Tavolacci, M.-P. Neuroenhancement in French and Romanian University Students, Motivations and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083880

Brumboiu I, Porrovecchio A, Peze T, Hurdiel R, Cazacu I, Mogosan C, Ladner J, Tavolacci M-P. Neuroenhancement in French and Romanian University Students, Motivations and Associated Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083880

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrumboiu, Irina, Alessandro Porrovecchio, Thierry Peze, Remy Hurdiel, Irina Cazacu, Cristina Mogosan, Joel Ladner, and Marie-Pierre Tavolacci. 2021. "Neuroenhancement in French and Romanian University Students, Motivations and Associated Factors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083880

APA StyleBrumboiu, I., Porrovecchio, A., Peze, T., Hurdiel, R., Cazacu, I., Mogosan, C., Ladner, J., & Tavolacci, M.-P. (2021). Neuroenhancement in French and Romanian University Students, Motivations and Associated Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083880