Characteristics of Multicomponent Interventions to Treat Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Extremely Cold Climates: A Systematic Review of a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy to Identify Studies

2.2. Study Selection and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Tool

2.5. Data Synthesis Strategy

3. Results

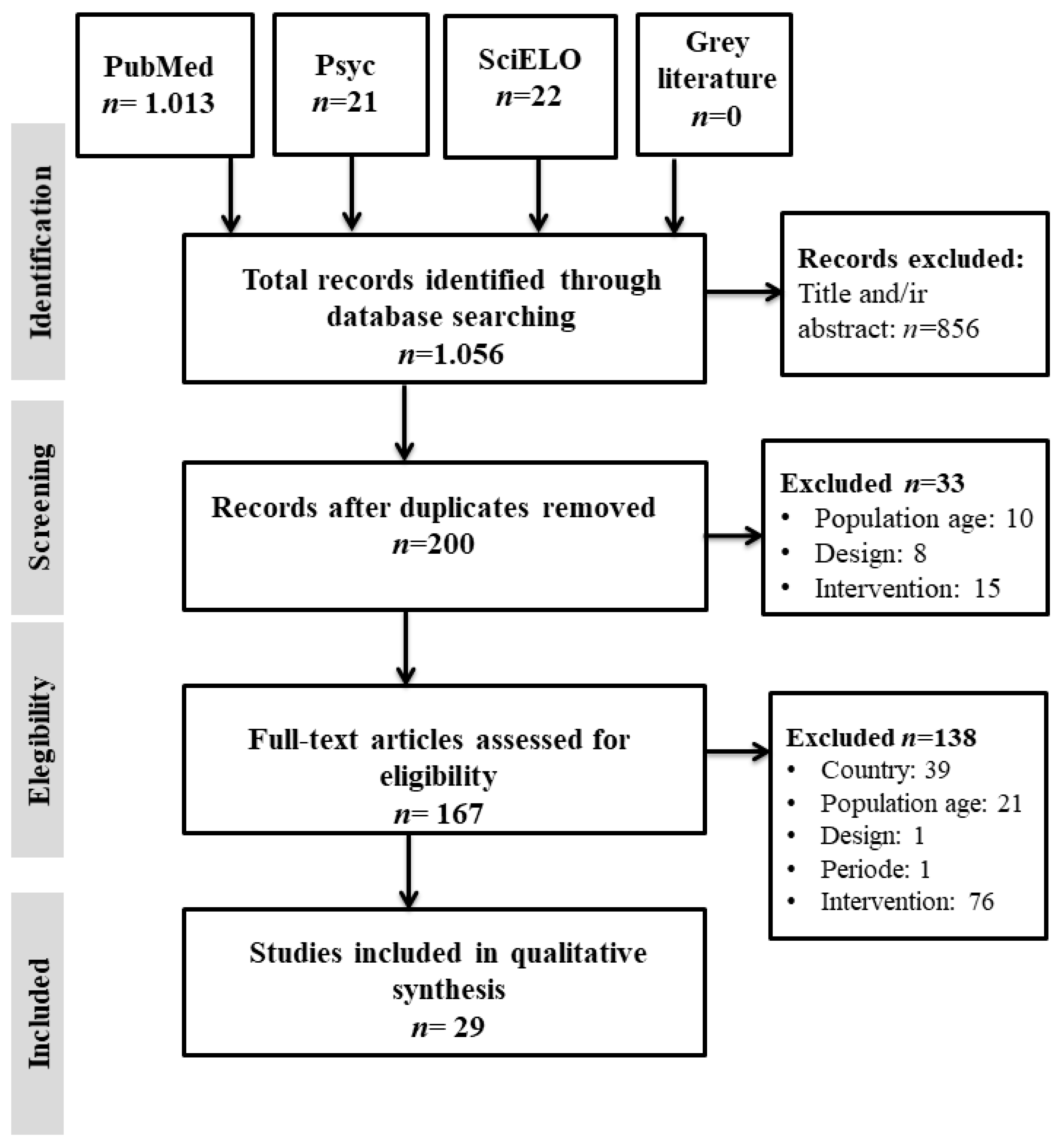

3.1. Search Outcome

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies Analyzed

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

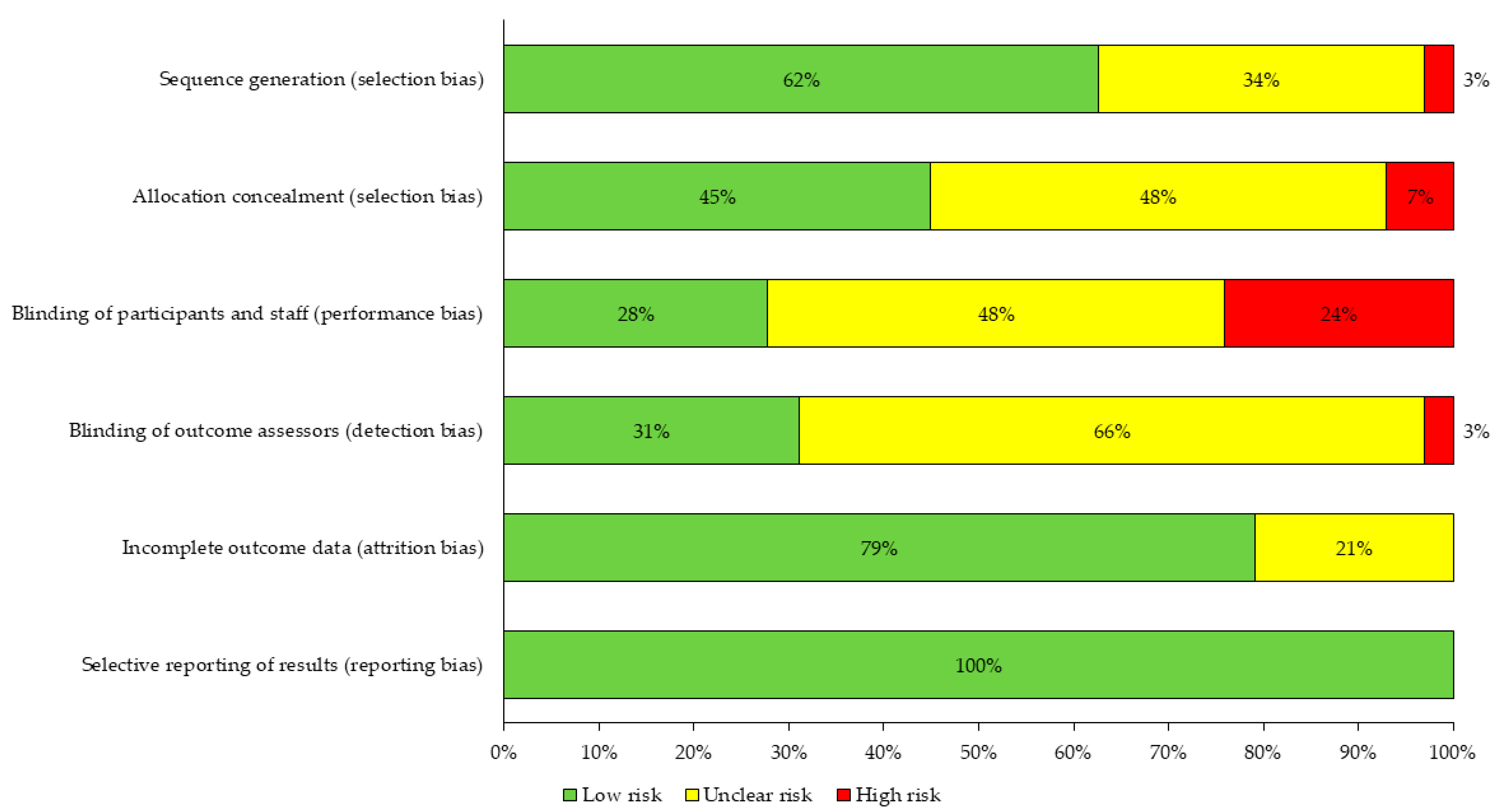

3.4. Main Characteristics of the Interventions

3.5. Effects of the Interventions on the Primary Outcome According to the Duration of the Intervention

3.6. Variables Studied in the Articles

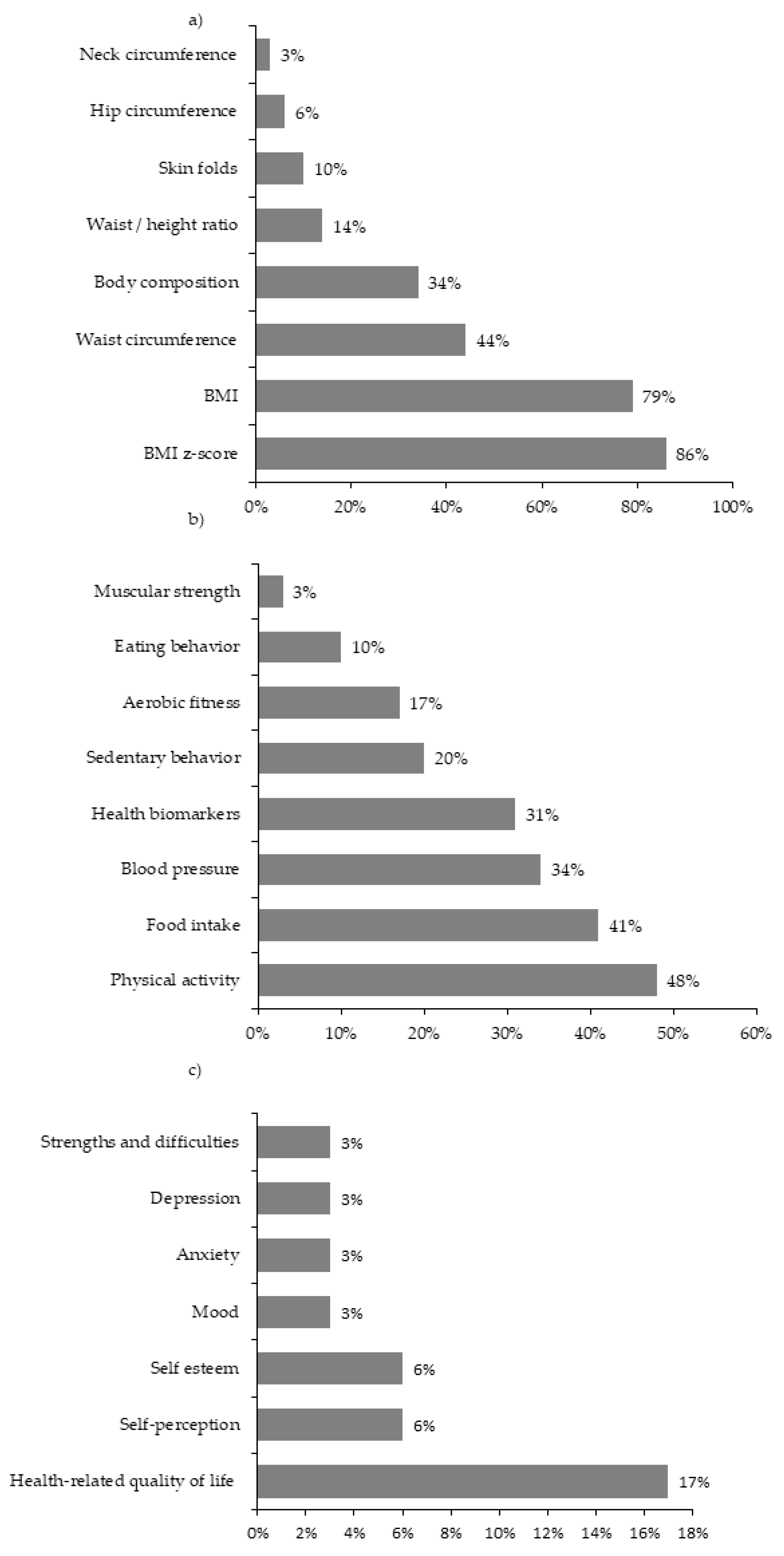

3.6.1. Nutritional Status

3.6.2. Physical and Health Condition

3.6.3. Mental Health

3.7. Assessment Instruments

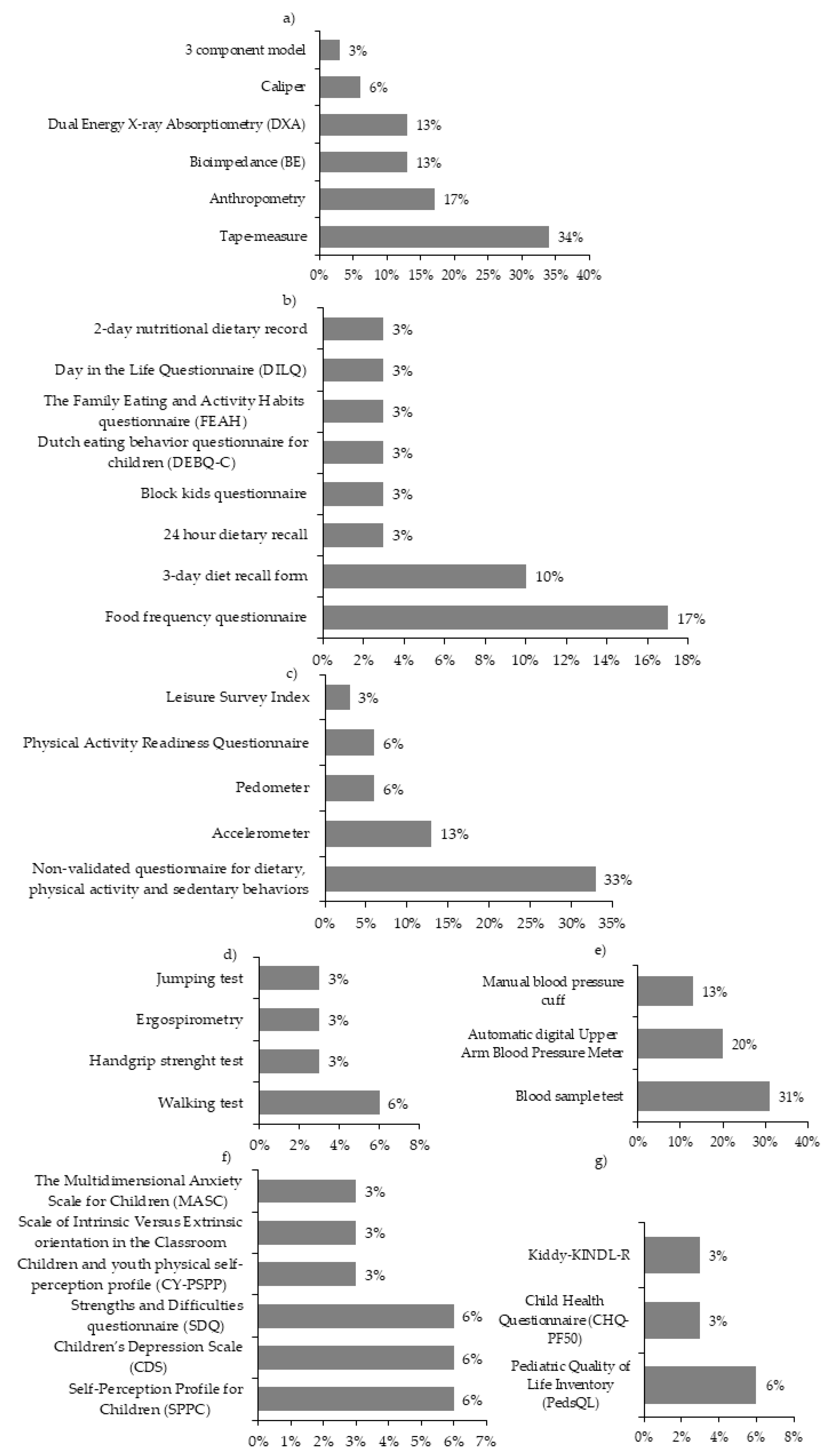

3.7.1. Nutritional Status

3.7.2. Physical and Health Condition

3.7.3. Psychological Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. General Characteristics of the Studies

4.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

4.3. Main Characteristics of the Interventions

4.4. Variables Studied and Assessment Instruments Used

5. Limitations and Contributions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levesque, R.J.R. Obesity and overweight. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schattenberg, J.M.; Schuppan, D. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: The therapeutic challenge of a global epidemic. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2011, 22, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, S.R.; Pratt, C.A.; Hayman, L.L. Reduction of risk for cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. Circulation 2011, 124, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rahilly, S. Human obesity and insulin resistance: Lessons from human genetics. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 44, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, A.; Franchi, L.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Body-Malapel, M.; Özören, N.; Brady, G. Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 35217–35223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Kesztyüs, D.; Wirt, T.; Kobel, S.; Schreiber, A.; Kettner, S.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Kilian, R.; Steinacker, J.M. Is central obesity associated with poorer health and health-related quality of life in primary school children? Cross-sectional results from the Baden-Württemberg Study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijga, A.H.; Scholtens, S.; Bemelmans, W.J.; de Jongste, J.C.; Kerkhof, M.; Schipper, M.; Sanders, E.A.; Gerritsen, J.; Brunekreef, B.; Smit, H.A. Comorbidities of obesity in school children: A cross-sectional study in the PIAMA birth cohort. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrotti, A.; Penta, L.; Zenzeri, L.; Agostinelli, S.; De Feo, P. Childhood obesity: Prevention and strategies of intervention. A systematic review of school-based interventions in primary schools. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2014, 37, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T. Lifestyle intervention in childhood obesity: Changes and challenges. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidell, J.C.; Halberstadt, J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adab, P.; Pallan, M.J.; Lancashire, E.R.; Hemming, K.; Frew, E.; Barrett, T.; Bhopal, R.; Cade, J.E.; Canaway, A.; Clarke, J.L.; et al. Effectiveness of a childhood obesity prevention programme delivered through schools, targeting 6 and 7 year olds: Cluster randomised controlled trial (WAVES study). BMJ 2018, 360, k211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: Implementation Plan: Executive Summary; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wabitsch, M.; Moss, A.; Kromeyer-Hauschild, K. Unexpected plateauing of childhood obesity rates in developed countries. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibzadeh, N. Why Physiologically Cold weather can Increase Obesity Rates? Int. Physiol. J. 2018, 2, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.K. Are the circumpolar inuit becoming obese? Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2007, 19, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, S.F. Central control of body temperature [version 1; referees: 3 approved]. F1000Research 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghetto, I.; Taladriz, C.; Lanzarini, E.; Romero, C. Plasma ghrelin levels in the late postoperative period of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Rev. Med. Chil. 2015, 143, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Anon. n.d. Top 15 Coldest Countries in the World 2020. Available online: https://earthnworld.com/coldest-countries-in-the-world/ (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Köppen, W. Versuch einer Klassifikation der Klimate, vorzugsweise nach ihren Beziehungen zur Pflanzenwelt (Examination of a climate classification preferably according to its relation to the flora). Geogr. Zeitschr. 1900, 6, 593–611, 657–679. [Google Scholar]

- Sarricolea, P.; Herrera-Ossandon, M.; Meseguer-Ruiz, Ó. Climatic regionalisation of continental Chile. J. Maps 2017, 13, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.; Butorovic, N.; Olave, C. Variación de la temperatura en punta arenas (chile) en los últimos 120 años. An. del Inst. la Patagon. 2009, 37, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, J.J. Review: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions, Version 5.1.0, published 3/2011. Julian, P.T. Higgins and Sally Green, Editors. Res. Synth. Methods 2011, 2, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marild, S.; Gronowitz, E.; Forsell, C.; Dahlgren, J.; Friberg, P. A controlled study of lifestyle treatment in primary care for children with obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2013, 8, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.R.; Hazell, T.J.; Vanstone, C.A.; Rodd, C.; Weiler, H.A. A family-centered lifestyle intervention for obese six-to eight-year-old children: Results from a one-year randomized controlled trial conducted in Montreal, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e453–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.T.; Huang, T.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Andersen, L.B.; Heidemann, M.; Møller, N.C. A multi-component day-camp weight-loss program is effective in reducing bmi in children after one year: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Lozano, P.; Scholz, K. A randomized clinical trial comparing delivery of behavioral pediatric obesity treatment using standard and enhanced motivational approaches. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdottir, T.; Sigurdardottir, Z.G.; Njardvik, U.; Olafsdottir, A.S.; Bjarnason, R. A randomized-controlled pilot study of Epstein’s family-based behavioural treatment for childhood obesity in a clinical setting in Iceland. Nord. Psychol. 2011, 63, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder-Lauridsen, N.M.; Birk, N.M.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Juul, A.; Andersen, L.B.; Pedersen, B.K.; Krogh-Madsen, R. A randomized controlled trial on a multicomponent intervention for overweight school-aged children-Copenhagen, Denmark. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Schaefer, A.; Winkel, K.; Finne, E.; Toschke, A.M.; Kolip, P. An effective lifestyle intervention in overweight children: Findings from a randomized controlled trial on ‘Obeldicks light’. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benestad, B.; Lekhal, S.; Småstuen, M.C.; Hertel, J.K.; Halsteinli, V.; Ødegård, R.A.; Hjelmesæth, J. Camp-based family treatment of childhood obesity: Randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsson, P.; Bohlin, A.; Bendito, A.; Svensson, A.; Klaesson, S. Five-year outpatient programme that provided children with continuous behavioural obesity treatment enjoyed high success rate. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.H.; Paluch, R.A.; Wrotniak, B.H.; Daniel, T.O.; Kilanowski, C.; Wilfley, D.; Finkelstein, E. Cost-effectiveness of family-based group treatment for child and parental obesity. Child. Obes. 2014, 10, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Saelens, B.E.; Stein, R.I.; Best, J.R.; Kolko, R.P.; Schechtman, K.B.; Wallendorf, M.; Welch, R.R.; Perri, M.G.; Epstein, L.H. Dose, content, and mediators of family-based treatment for childhood obesity a multisite randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.M.; Hertel, N.T.; Mølgaard, C.; Christensen, R.D.; Husby, S.; Jarbøl, D.E. Early intervention for childhood overweight: A randomized trial in general practice. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2015, 33, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; Martin, X.E.; Bucher Della Torre, S.; Von Haller, L.; Ells, L.J.; Herrmann, F.R.; Aggoun, Y. Effectiveness of individual and group programmes to treat obesity and reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors in pre-pubertal children. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie-Rosett, J.; Groisman-Perelstein, A.E.; Diamantis, P.M.; Jimenez, C.C.; Shankar, V.; Conlon, B.A.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Isasi, C.R.; Martin, S.N.; Ginsberg, M.; et al. Embedding weight management into safety-net pediatric primary care: Randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. 2018, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschburger, P.; Kroeller, K.; Haerting, J.; Unverzagt, S.; van Egmond-Fröhlich, A. Empowering Parents of Obese Children (EPOC): A randomized controlled trial on additional long-term weight effects of parent training. Appetite 2016, 103, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christison, A.L.; Evans, T.A.; Bleess, B.B.; Wang, H.; Aldag, J.C.; Binns, H.J. Exergaming for Health: A Randomized Study of Community-Based Exergaming Curriculum in Pediatric Weight Management. Games Health J. 2016, 5, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croker, H.; Viner, R.M.; Nicholls, D.; Haroun, D.; Chadwick, P.; Edwards, C.; Wells, J.C.; Wardle, J. Family-based behavioural treatment of childhood obesity in a UK national health service setting: Randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkvoll, A.; Grimsgaard, S.; Steinsbekk, S.; Flægstad, T.; Njølstad, I. Health in overweight children: 2-Year follow-up of Finnmark Activity School-A randomised trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle-Baker, P.K.; Venner, A.A.; Lyon, M.E.; Fung, T. Impact of a combined diet and progressive exercise intervention for overweight and obese children: The BEHIP study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavainen, M.P.; Korppi, M.O.; Nuutinen, O.M. Clinical efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counseling. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njardvik, U.; Gunnarsdottir, T.; Olafsdottir, A.S.; Craighead, L.W.; Boles, R.E.; Bjarnason, R. Incorporating appetite awareness training within family-based behavioral treatment of pediatric obesity: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerards, S.M.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Gubbels, J.S.; Van Buuren, S.; Hamers, F.J.; Jansen, M.W.; Van Der Goot, O.H.; De Vries, N.K.; Sanders, M.R.; Kremers, S.P. The effectiveness of lifestyle triple P in the Netherlands: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutelle, K.N.; Cafri, G.; Crow, S.J. Parent-only treatment for childhood obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Obesity 2011, 19, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, W.; Fleming, J.; Kamal, A.; Hamborg, T.; A Khan, K.; Griffiths, F.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Stallard, N.; Petrou, S.; Simkiss, D.; et al. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the ‘Families for Health’ programme to reduce obesity in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Han, W.; Yamauchi, T. Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of a Combined Intervention of Rope Skipping and Nutrition Education for Overweight Children in Northeast China. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2019, 31, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovitz, S.D.; Berge, J.M.; Wetzsteon, R.J.; Sherwood, N.E.; Hannan, P.J.; Himes, J.H. Stage 1 treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity: A pilot and feasibility randomized controlled trial. Child. Obes. 2014, 10, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Niet, J.; Timman, R.; Bauer, S.; van den Akker, E.; Buijks, H.; de Klerk, C.; Kordy, H.; Passchier, J. The effect of a short message service maintenance treatment on body mass index and psychological well-being in overweight and obese children: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, N.E.; Levy, R.L.; Seburg, E.M.; Crain, A.L.; Langer, S.L.; JaKa, M.M.; Kunin-Batson, A.; Jeffery, R.W. The Healthy Homes/Healthy Kids 5-10 Obesity Prevention Trial: 12 and 24-month outcomes. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Scholz, K.; Walters, K.; Simoni, J.M.; Wright, D.R. Two Pilot Randomized Trials to Examine Feasibility and Impact of Treated Parents as Peer Interventionists in Family-Based Pediatric Weight Management. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summerbell, C.D.; Ashton, V.; Campbell, K.J.; Edmunds, L.; Kelly, S.; Waters, E. Interventions for treating obesity in children. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.; Kirk, S.; Claytor, R.; Khoury, P.; Grieme, J.; Santangelo, M.; Daniels, S. Predictors of attrition from a pediatric weight management program. J. Pediatr. 2004, 144, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braet, C.; Van Winckel, M.; Van Leeuwen, K. Follow-up results of different treatment programs for obese children. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 1997, 86, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli, A.; Faith, M.S.; Allison, D.B.; Gallagher, D.; Chiumello, G.; Heymsfield, S.B. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity among children and adolescents: A validation study. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, R.; Díaz, N.; Muzzo, S. Variaciones del índice de masa corporal (IMC) de acuerdo al grado de desarrollo puberal alcanzado. Rev. Med. Chile 2004, 132, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cole, T.J.; Faith, M.S.; Pietrobelli, A.; Heo, M. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neovius, M.G.; Linné, Y.M.; Barkeling, B.S.; Rossner, S.O. Sensitivity and specificity of classification systems for fatness in adolescents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.H.; McCurley, J.; Wing, R.R.; Valoski, A. Five-year follow-up of family-based behavioral treatments for childhood obesity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 58, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzmann, K.M.; Beech, B.M. Family-based interventions for pediatric obesity: Methodological and conceptual challenges from family psychology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, L.H.; Valoski, A.; Wing, R.R.; McCurley, J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994, 13, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrotniak, B.H.; Epstein, L.H.; Paluch, R.A.; Roemmich, J.N. Parent Weight Change as a Predictor of Child Weight Change in Family-Based Behavioral Obesity Treatment. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, L.H. Family-based behavioural intervention for obese children. Int. J. Obes. 1996, 20, S14–S21. [Google Scholar]

- Luttikhuis, H.O.; Baur, L.; Jansen, H.; Shrewsbury, V.A.; O’Malley, C.; Stolk, R.P.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, D.; Barkan, S.; Epstein, Y.; Friedland, O.; Kowen, G.; Eliakim, A. Short- and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioral- physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e443–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, L.H.; Roemmich, J.N.; Raynor, H.A. Behavioral therapy in the treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 48, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.; Vio, F.; Leyton, B.; Cerda, R.; Olivares, S.; Uauy, R.; Albala, C. Estrategia de promoción de la salud en escolares de educación básica municipalizada de la comuna de casablanca, chile. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2005, 32, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyna, N.I.; Gussinyer, S.; Carrascosa, A. Niñ@s en Movimiento, un programa para el tratamiento de la obesidad infantil. Med. Clin. 2007, 129, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chueca, M.; Azcona, C.; Oyarzábal, M. Obesidad infantil Childhood obesity. An. Sis San Navar. 2002, 25, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, M.; Ward, L.C. New techniques in nutritional assessment: Body composition methods. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gortmaker, S.L.; Must, A.; Perrin, J.M.; Sobol, A.M.; Dietz, W.H. Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1994, 153, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ref. | Main Author, Year, Contry | Sample Size | Adherence | Reason for Exclusion | Recruiting | Age | Sex | Inclusion Criteria | Place of the Intervention | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♀ | ♂ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| % | LT | PR | AT | NS | HE | DNMC | DWC | HC | EC | COM | mean | % | % | BMI | W/H | NS | HC | EC | UC | CC | NS | |||

| [27] | Mårild S. (2013), Sweden | 265 | 93 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 11 | 58 | 42 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [28] | Cohen T. (2016) Canada | 78 | 93 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 58 | 42 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [29] | Traberg C. (2016) Denmark | 115 | 75 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 12 | 45 | 55 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| [30] | Saelens B. (2013) USA | 89 | 80 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 9 | 67 | 33 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| [31] | Gunnarsdottir T. (2014) Iceland | 16 | 81 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 10 | 68 | 32 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [32] | Harder-Lauridsen N. (2014) Denmark | 38 | 92 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 8 | 80 | 20 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| [33] | Reinehr T. (2010) Germany | 66 | 91 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 11 | 58 | 42 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| [34] | Benestad B. (2017) Norway | 94 | 73 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 10 | 50 | 50 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [35] | Danielsson P. (2016) Sweden | 589 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 9 | 46 | 54 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [36] | Epstein L. (2014) USA | 101 | 66 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 11 | 60 | 40 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [37] | Wilfley D. (2017) USA | 172 | 93 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 9 | 61 | 39 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [38] | Larsen L. (2015) Denmark | 80 | 93 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 64 | 36 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| [39] | Farpour-Lambert N. (2019) Switzerland | 74 | 89 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 9 | 51 | 49 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [40] | Wylie-Rosett J. (2018) USA | 366 | 73 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 9 | 52 | 48 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [41] | Warschburger P. (2016) Germany | 685 | 76 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 11 | 52 | 48 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [42] | Christison A. (2016) USA | 84 | 95 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 10 | 54 | 46 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| [43] | Croker H. (2012) England | 72 | 79 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 70 | 30 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [44] | Kokkvoll A. (2015) Norway | 97 | 85 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 10 | 54 | 46 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [45] | Doyle-Baker P. (2011) Canada | 27 | 93 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 8 | 52 | 48 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| [46] | Kalavainen M. (2012) Finland | 70 | 97 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 8 | 60 | 40 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [47] | Njardvik U. (2018) Iceland | 90 | 67 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 11 | 45 | 55 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [48] | Gerards S. (2015) The Netherlands | 86 | 85 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 7 | 55 | 45 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [49] | Boutelle K. (2011) USA | 80 | 63 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 10 | 60 | 40 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [50] | Robertson W. (2017) England | 105 | 84 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 65 | 35 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| [51] | Ming Hao M. (2019) China | 229 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 10 | 45 | 55 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| [52] | Steven D. (2014) USA | 72 | 97 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 6 | 36 | 64 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [53] | de Niet J. (2012) Nederlands | 144 | 98 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 10 | 64 | 36 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [54] | Sherwood N. (2018) USA | 421 | 86 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 6 | 50 | 50 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| [55] | Saelens B. (2017) USA | 29 | 82 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 10 | 59 | 41 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Ref. | Group | Participants | Interventions Characteristics | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Main Outcome | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dur. Months | Tra | Professional Responsible | Phys. Act | Education | Beh. Ter | Nutrition | BMI | BMI | BMI | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P | C | P-C | FAM | Nur | Nut | PA | MD | Psy | SW | Other | NS | Rec | PEP | RA | Rec | Cond | Rec | NP | RA | (kg/t2) | (z-) | (SD) | SC | MT | NSC | ||||

| [27] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [28] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [29] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| [30] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [31] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 4 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| [32] | IG | - | - | - | 1 | 5 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [33] | IG | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [34] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| IG2 | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [35] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 60 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| [36] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| [37] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [38] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [39] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [40] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| [41] | IG1 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 12 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [42] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| [43] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| [44] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 24 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| IG2 | - | - | - | - | 24 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [45] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 2.5 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [46] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| [47] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| [48] | IG | 1 | - | - | - | 4 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| [49] | IG1 | 1 | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [50] | IG | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| [51] | IG1 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| IG2 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| IG3 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [52] | IG | - | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| [53] | IG | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| [54] | IG | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| [55] | IG1 | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| IG2 | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Duration of the Intervention: 6 and 12 Months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | Education | Behavioral Therapy | Nutrition | |||||

| Statistically significant change over the primary outcomes | Recreational activities | Recommendations | Physical exercise program | Nutrition program | Recommendations | Cooking class | ||

| ≤6 months | 100% | 59% | 83% | 100% | 65% | 100% | 63% | 50% |

| ≥12 months | 67% | 100% | 100% | 92% | 91% | 100% | 75% | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albornoz-Guerrero, J.; García, S.; Sevilla, G.G.P.d.; Cigarroa, I.; Zapata-Lamana, R. Characteristics of Multicomponent Interventions to Treat Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Extremely Cold Climates: A Systematic Review of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063098

Albornoz-Guerrero J, García S, Sevilla GGPd, Cigarroa I, Zapata-Lamana R. Characteristics of Multicomponent Interventions to Treat Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Extremely Cold Climates: A Systematic Review of a Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063098

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbornoz-Guerrero, Javier, Sonia García, Guillermo García Pérez de Sevilla, Igor Cigarroa, and Rafael Zapata-Lamana. 2021. "Characteristics of Multicomponent Interventions to Treat Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Extremely Cold Climates: A Systematic Review of a Randomized Controlled Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063098

APA StyleAlbornoz-Guerrero, J., García, S., Sevilla, G. G. P. d., Cigarroa, I., & Zapata-Lamana, R. (2021). Characteristics of Multicomponent Interventions to Treat Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Extremely Cold Climates: A Systematic Review of a Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063098