“The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

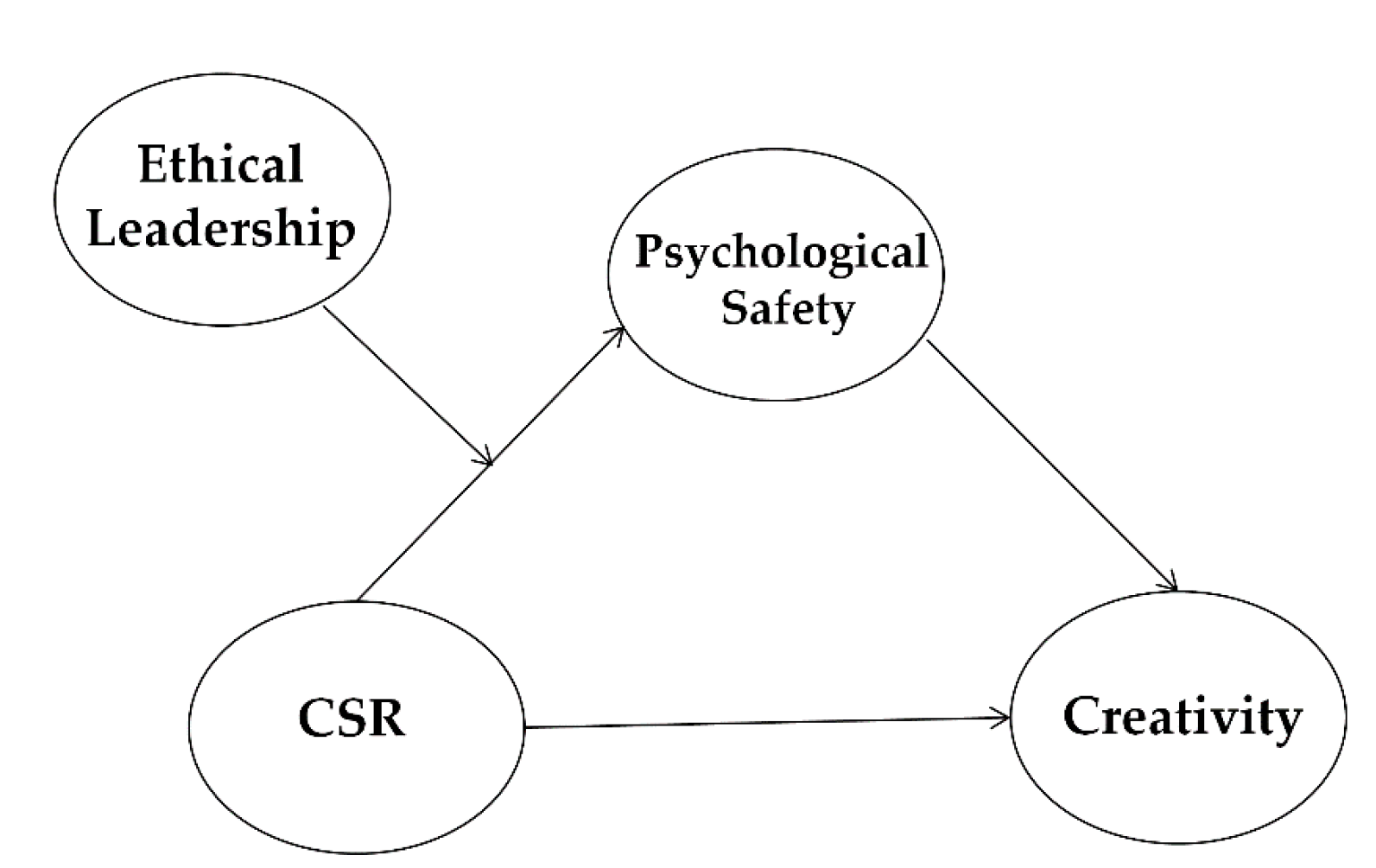

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Psychological Safety

2.2. Psychological Safety and Employee Creativity

2.3. Mediating Role of Psychological Safety between CSR and Employee Creativity

2.4. Moderation Effect of Ethical Leadership in the CSR–Psychological Safety Link

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. CSR (Time Point 1, Collected from Employees)

3.2.2. Psychological Safety (Time Point 2, Collected from Employees)

3.2.3. Creativity in Individual Employees (Time Point 3, Collected from Immediate Supervisors of Employees)

3.2.4. Ethical Leadership (Time Point 1, Collected from Employees)

3.2.5. Control Variables (Time Point 2, Collected from Employees)

3.3. Analytical Approach

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

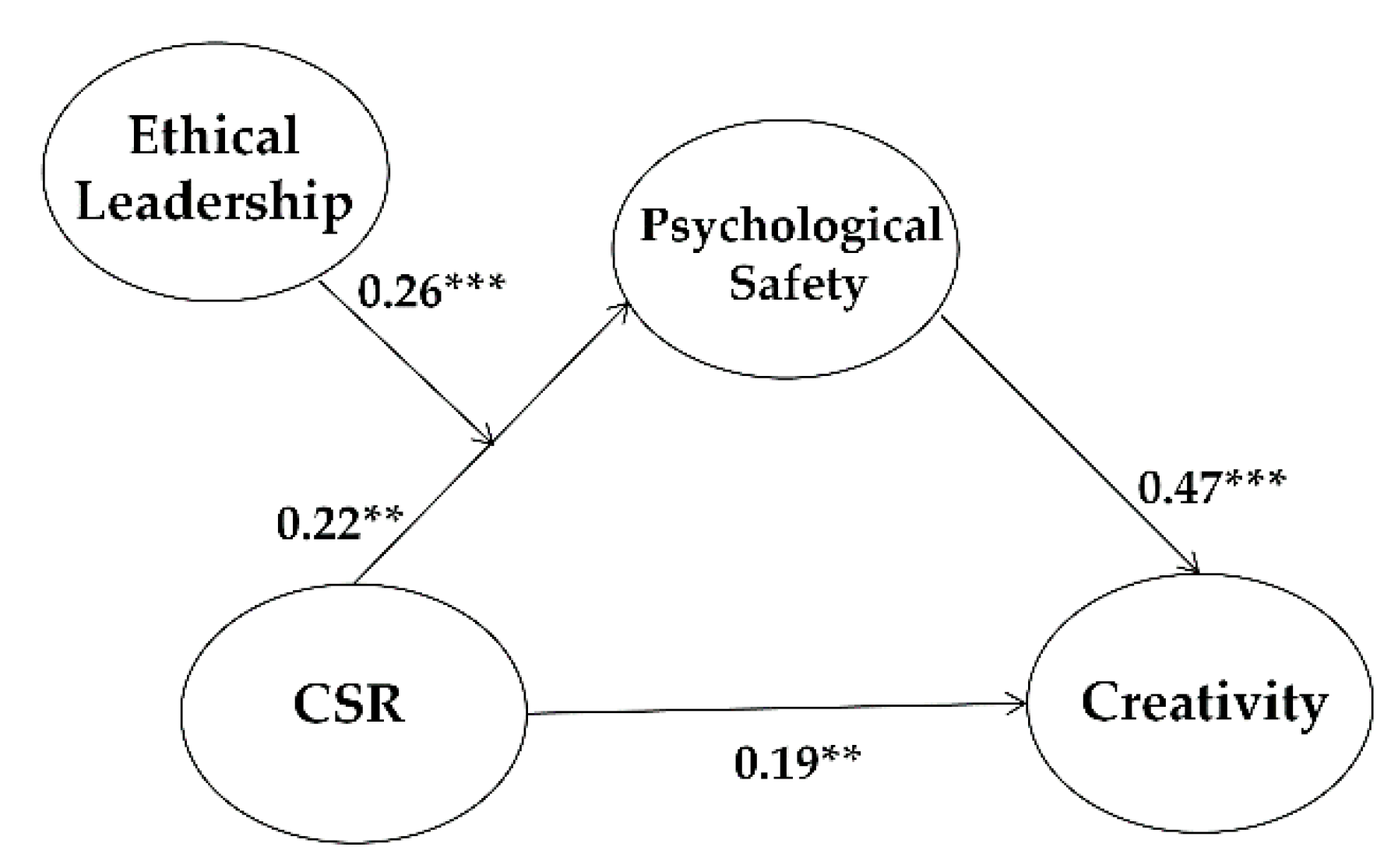

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. Results of Mediation Analysis

4.3.2. Bootstrapping

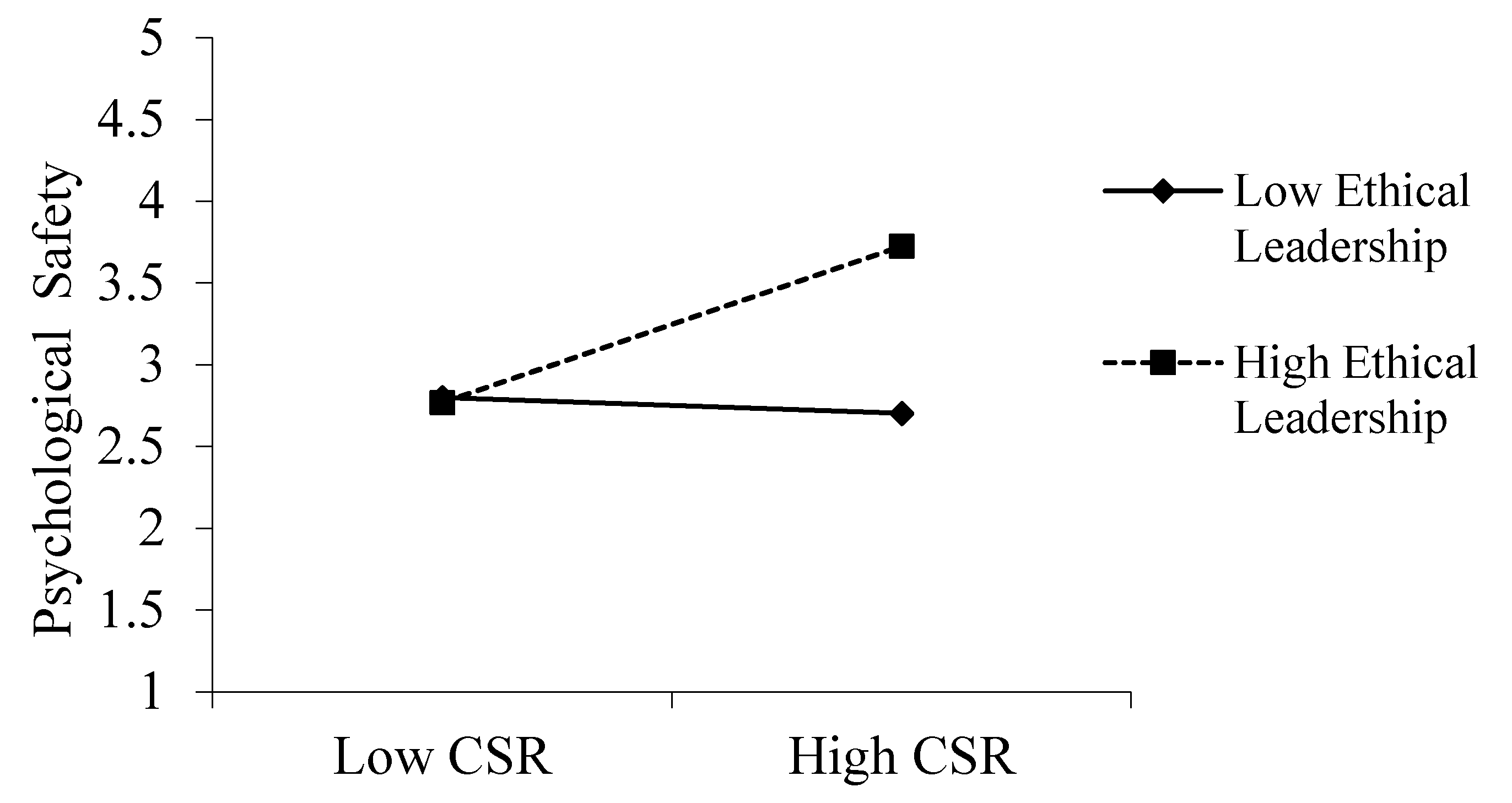

4.4. Results of Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguinis, H. Organizational Responsibility: Doing Good and Doing Well. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Correlation or Misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.; Berman, S. A Brand New Brand of Corporate Social Performance. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.; Ruth, V.; Rupp, D.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multi-level Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social respon-sibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social respon-sibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S. Corporate Reputation and Social Performance: The Importance of Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Činčalová, S.; Hedija, V. Firm Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case of Czech Transportation and Storage Industry. Sustain. J. Rec. 2020, 12, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we Know and Don’t Know about Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological micro-foundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Org. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Rupp, D.E. Social responsibility IN and OF organizations: The psychology of corporate social responsibility among organizational members. In 333-Handbook of Industrial; Anderson, N., Ones, D., Sinangil, H., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological, Person-Centric, and Progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment. Inter. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency Matters! How and When Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Employees’ Organizational Identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.A.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social re-sponsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Fron. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The Effects of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Attitudes. Bus. Ethic Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee–Company Identification. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.-O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Akhouri, A. CSR perceptions and employee creativity: Examining serial mediation effects of meaningful-ness and work engagement. Soc. Res. J. 2019, 15, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Cit. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 1988, 10, 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Groysberg, B.; Lee, L.-E.; Nanda, A. Can They Take It With Them? The Portability of Star Knowledge Workers’ Performance. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen, B.R.; Lewicki, R.J.; Tomlinson, E.C. Supervisory guidance and behavioral integrity: Relationships with em-ployee citizenship and deviant behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Poland, T.; Minton, J.W.; Sheppard, B.H. Dishonesty as deviance: A typology of workplace dishonesty and contributing factors. In Research on Negotiation in Organizations; Lewicki, R., Bies, R., Shep-pard, B., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary-Kelly, A.M.; Griffin, R.W.; Glew, D.J. Organization-motivated aggression: A research framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, T.; Leroy, H.; Collewaert, V.; Masschelein, S. How leader alignment of words and deeds affects followers: A me-ta-analysis of behavioral integrity research. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S.A.; Simons, T.; Leroy, H.; Tuleja, E.A. What is in it for me? Middle manager behavioral integrity and perfor-mance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimbush, J.C. The Effect of Cognitive Moral Development and Supverisory Influence on Subordinates’ Ethical Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic 1999, 18, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, P.B.; Dzindolet, M. Social influence, creativity and innovation. Soc. Influ. 2008, 3, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J.R.; Simester, D.I.; Wernerfelt, B. Internal customers and internal suppliers. J. Mark. Res. 1996, 33, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Carmeli, A. Alive and creating: The mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psy-chological safety and creative work involvement. J. Org. Behav. 2009, 30, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A.; Richter, A.W. Climates and Cultures for Innovation and Creativity at Work. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Zhou, J., Shalley, C.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Winn, B. Virtuousness in Organizations. In Virtuousness in Organizations; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Locander, W.B. Critical Role of Leadership on Ethical Climate and Salesperson Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 86, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, C.P.; Harrington, S.J. The Relationship of Communication, Ethical Work Climate, and Trust to Commitment and Innovation. J. Bus. Ethic 2000, 25, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Involvement in Creative Tasks in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shalley, C.E. Research on Employee Creativity: A Critical Review and Directions for Future Research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 165–217. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, R.; Fiske, S.T. Outcome dependency and attention to inconsistent information. J. Pes. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T.J. Doing Good Is Not Enough, You Should Have Been Authentic: The Medi-ating Effect of Organizational Identification, and Moderating Effect of Authentic Leadership between CSR and Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.Y. Does a Good Firm Breed Good Organizational Citizens? The Moderat-ing Role of Perspective Taking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-J.; Park, S.; Kim, T.-H. The effect of transformational leadership on team creativity: Sequential mediating effect of employee’s psychological safety and creativity. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2019, 27, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M.; Graen, G.B. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of TRAITS AND relationships. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Bian, L. Cognitive Team Diversity and Individual Team Member Creativity: A Cross-Level Interaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A Researcher’s Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods. 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows, 2nd ed.; Pal-grave: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, D.R.; Anseel, F.; Kluger, A.N.; Lloyd, K.J.; Turjeman-Levi, Y. Mere listening effect on creativity and the medi-ating role of psychological safety. Psycho. Aes. Creat. Art 2018, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 47.3% |

| Female | 52.7% |

| Age (years) | |

| 20s | 21.2% |

| 30s | 25.4% |

| 40s | 26.1% |

| 50s | 27.3% |

| Education | |

| Senior high school and below | 14.5% |

| Community college | 20.3% |

| Undergraduate | 58.2% |

| Postgraduate and above | 7.1% |

| Position | |

| Staff | 30.2% |

| Assistant manager | 24.4% |

| Manager or deputy general manager | 22.2% |

| Department/general manager or director and above | 23.2% |

| Occupation | |

| Office workers | 63.7% |

| Administrative positions | 19.3% |

| Sales and marketing | 6.4% |

| Manufacturing | 4.5% |

| Education | 1.6% |

| Other | 4.5% |

| Tenure (months) | |

| Below 50 | 51.4% |

| 50 to 100 | 19.0% |

| 100 to 150 | 13.8% |

| 150 to 200 | 5.5% |

| 200 to 250 | 4.5% |

| Above 250 | 5.8% |

| Firm size | |

| Above 500 members | 47.9% |

| 300–499 members | 12.2% |

| 100–299 members | 15.1% |

| 50–99 members | 6.4% |

| Below 50 members | 18.3% |

| Industry Type | |

| Manufacturing | 24.1% |

| Services | 14.8% |

| Construction | 12.9% |

| Information services and telecommunications | 10.9% |

| Education | 9.3% |

| Health and welfare | 8.4% |

| Public service and administration | 7.8% |

| Financial/insurance | 3.9% |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSR | 3.19 | 0.62 | - | |||||||

| 2. Ethical leadership | 3.12 | 0.67 | 0.49 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Psychological safety | 3.10 | 0.64 | 0.32 ** | 0.33 ** | - | |||||

| 4. Creativity | 3.17 | 0.64 | 0.32 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.43 ** | - | ||||

| 5. Gender | 1.53 | 0.50 | −0.16 ** | −0.12 * | 0.03 | −0.04 | - | |||

| 6. Position | 2.71 | 1.62 | 0.12 * | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.16 ** | −0.30 ** | - | ||

| 7. Tenure (months) | 93.10 | 95.02 | 0.22 ** | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 * | −0.18 ** | 0.37 ** | - | |

| 8. Education | 2.56 | 0.82 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.08 | - |

| 9. Industry type | - | - | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 25 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Model Comparison | Δdf | Δχ2 | Preference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor | 864.50 | 213 | 0.818 | 0.783 | 0.099 | 1-factor vs. 2-factor | 1 | 166.81 | 2-factor |

| 2-factor | 697.69 | 212 | 0.864 | 0.838 | 0.086 | ||||

| 3-factor | 356.42 | 210 | 0.959 | 0.951 | 0.047 | 2-factor vs. 3-factor | 2 | 341.27 | 3-factor |

| Model | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal CSR -> Creativity | 0.187 | 0.100 | 0.288 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, T.-H. “The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062968

Kim B-J, Kim M-J, Kim T-H. “The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062968

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Byung-Jik, Min-Jik Kim, and Tae-Hyun Kim. 2021. "“The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062968

APA StyleKim, B.-J., Kim, M.-J., & Kim, T.-H. (2021). “The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062968