A Relational Approach to the Design for Peer Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Support and Aging

1.2. Designing for Peer Support

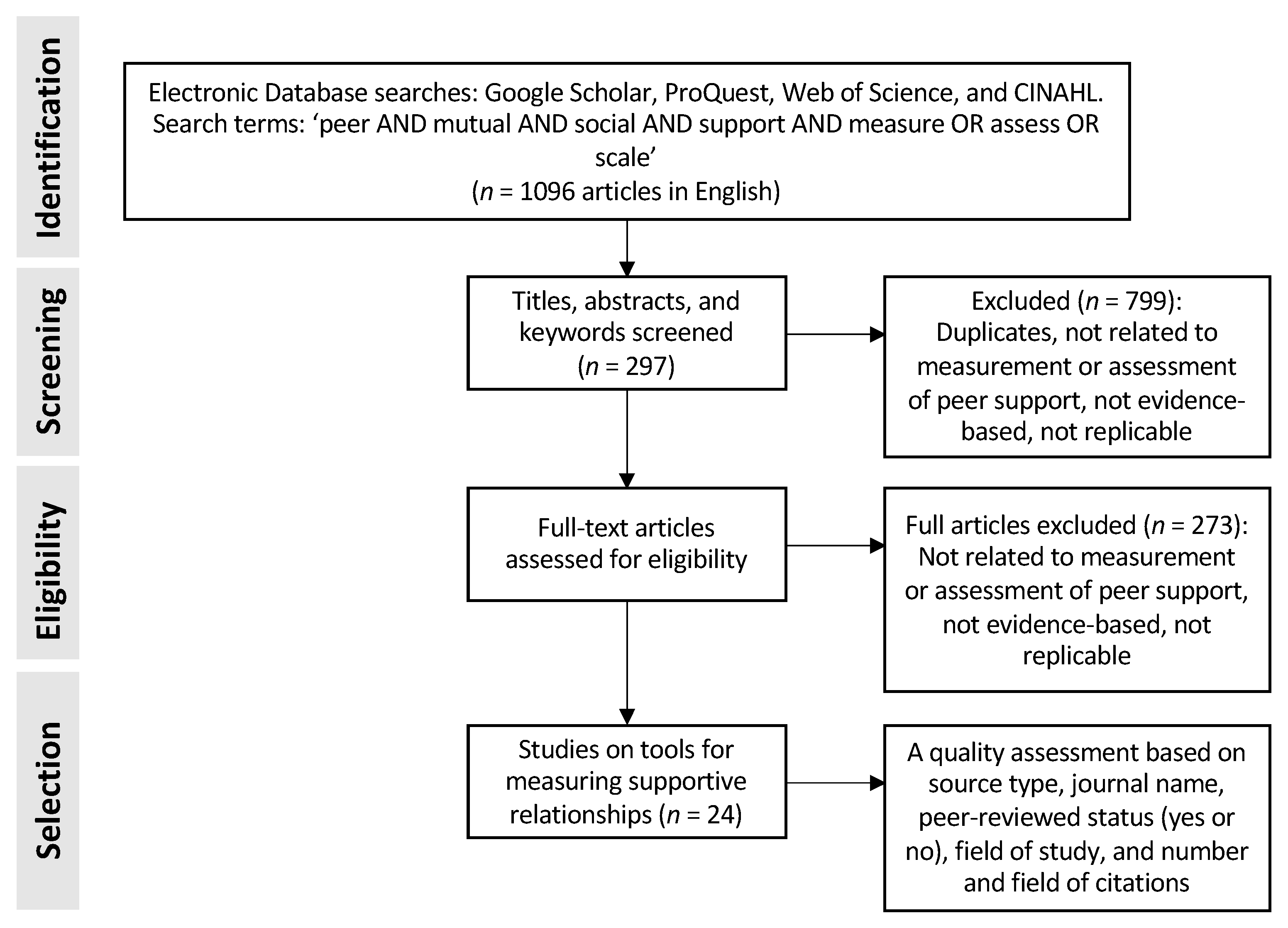

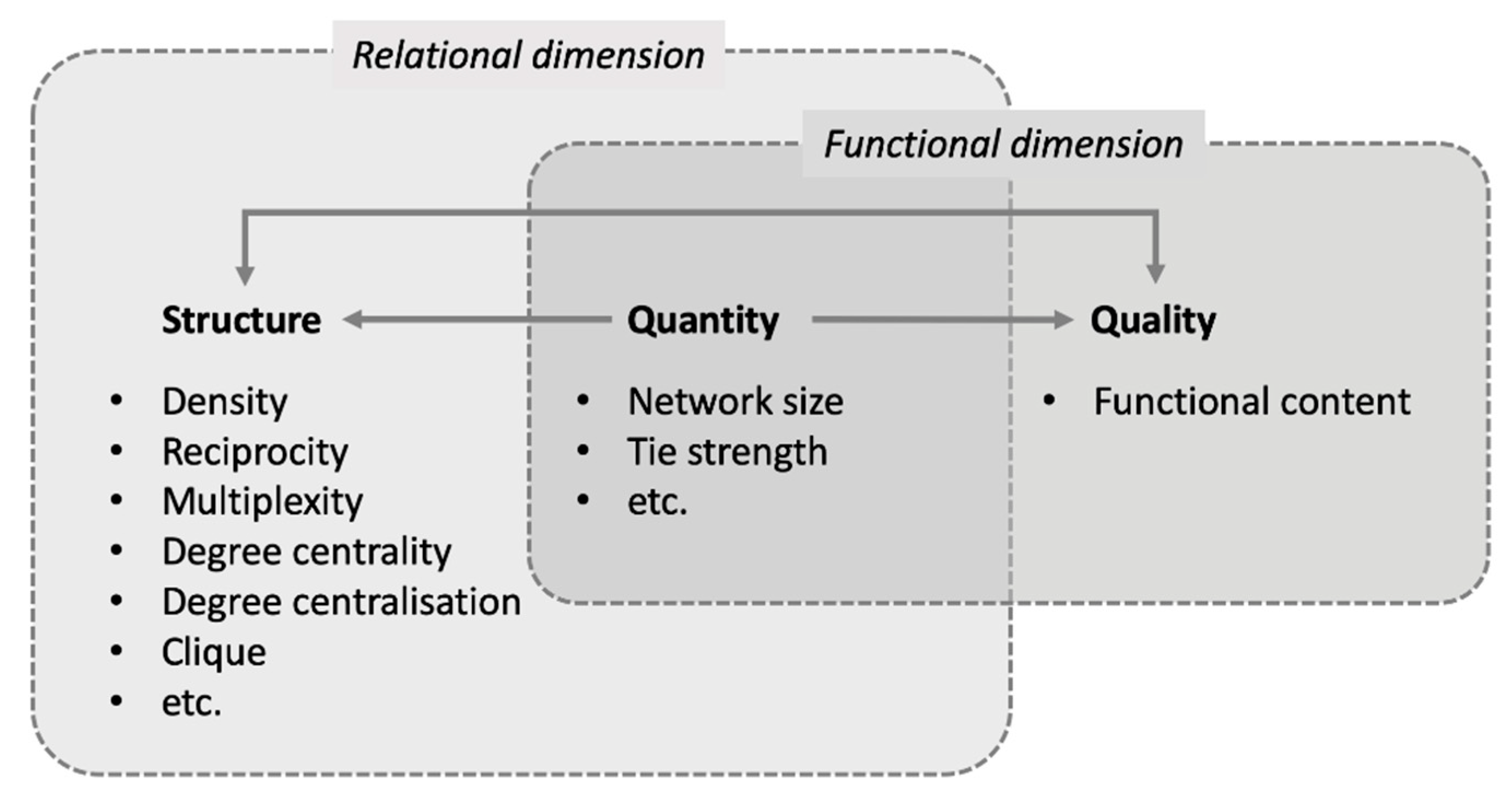

1.3. Measuring Social (or Peer) Support

2. Methods

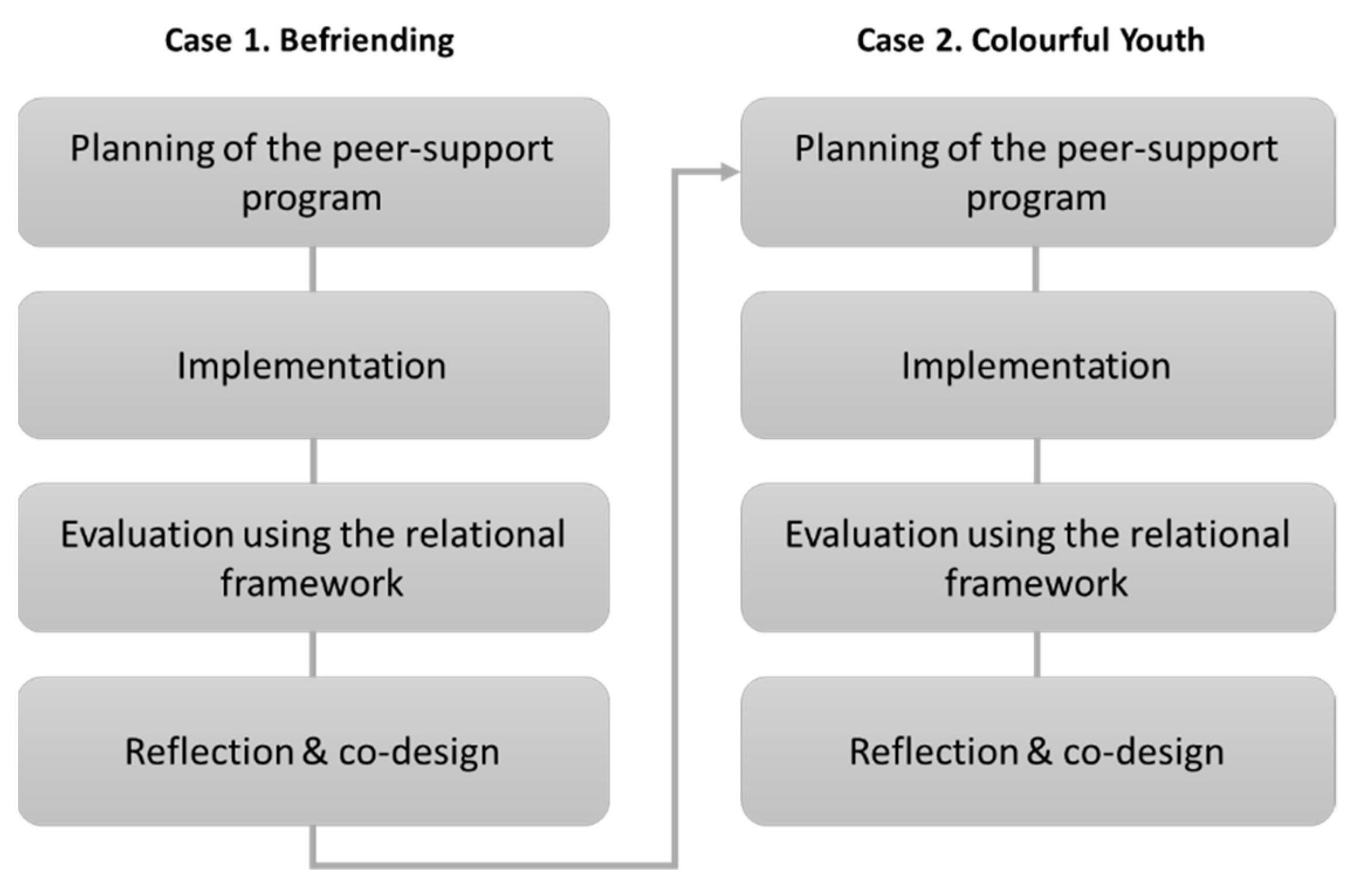

2.1. Case Studies

2.2. Data Collection

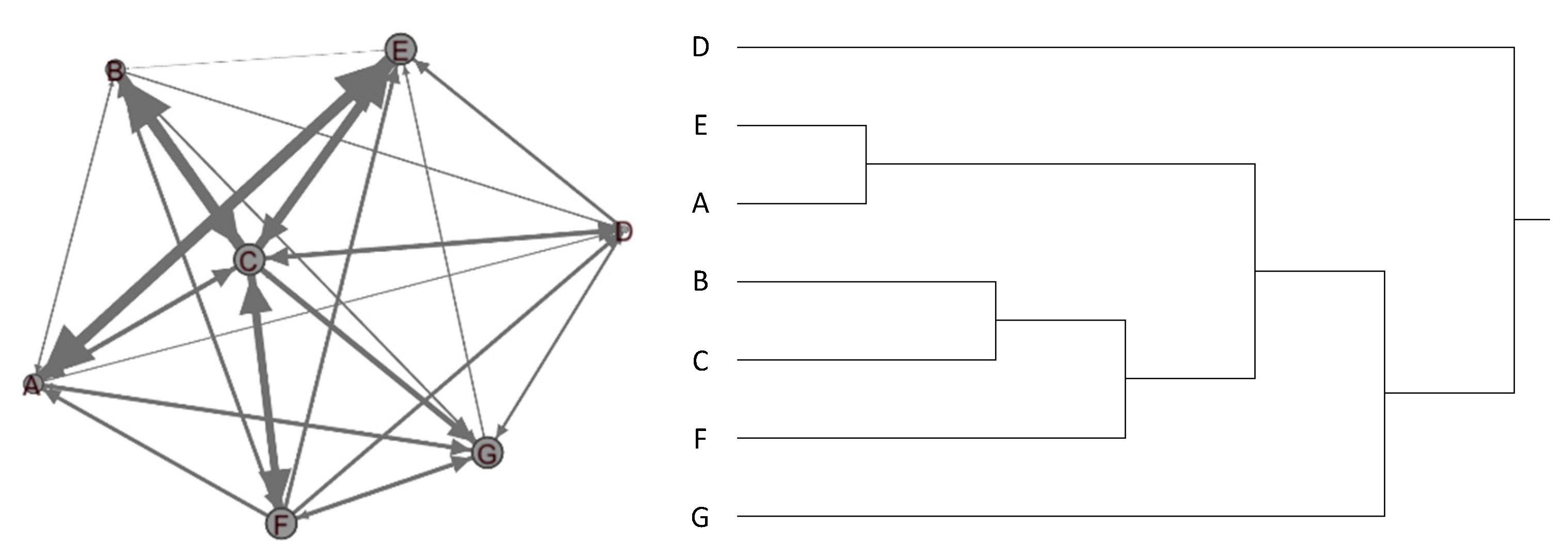

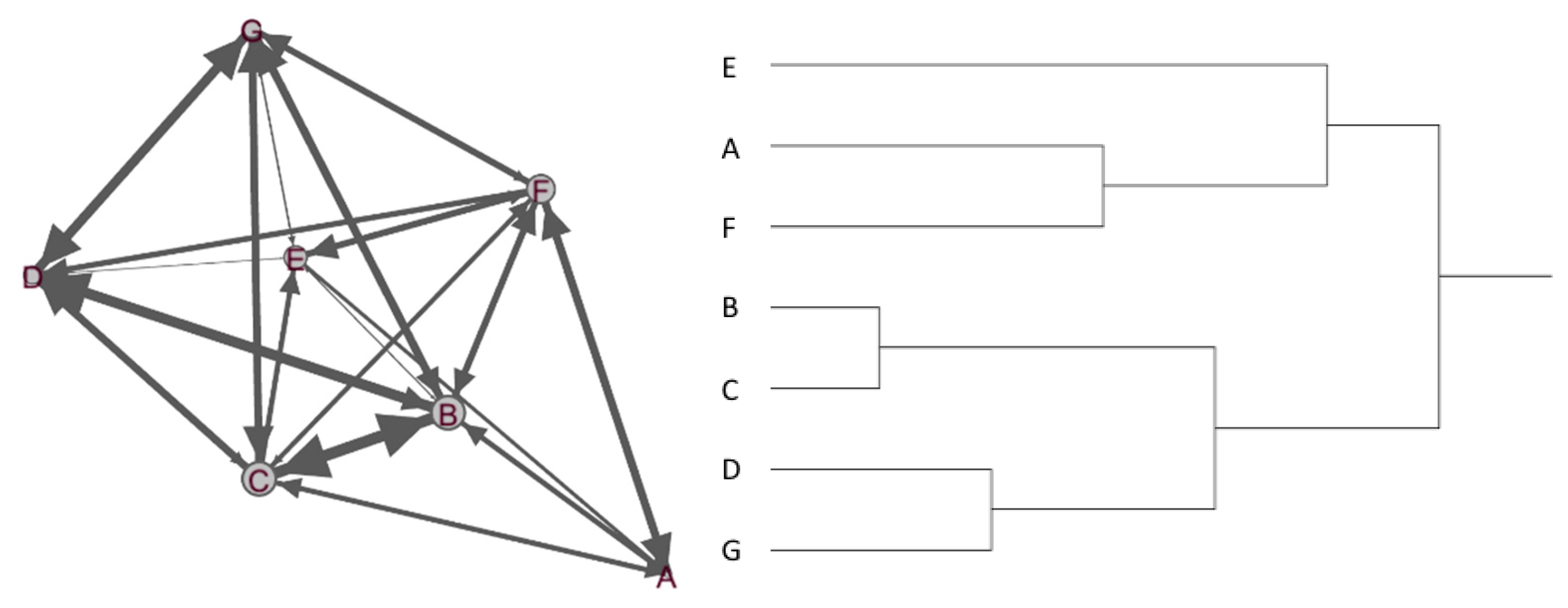

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Befriending

3.1.1. Network Quantity

3.1.2. Network Quality

3.1.3. Network Structure

3.1.4. Intervention Ideas

3.2. Colourful Youth

3.2.1. Network Quantity

3.2.2. Network Quality

3.2.3. Network Structure

3.2.4. Intervention Ideas

3.3. Other Findings

3.4. Program Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Preconditions for Building Peer-Support Relationships

4.1.1. Mitigating Network Fragmentation

4.1.2. Aligning Participant Needs

4.1.3. Fostering Freedom and Truthfulness

4.1.4. Defeating Stereotypes

4.1.5. Self-Identification

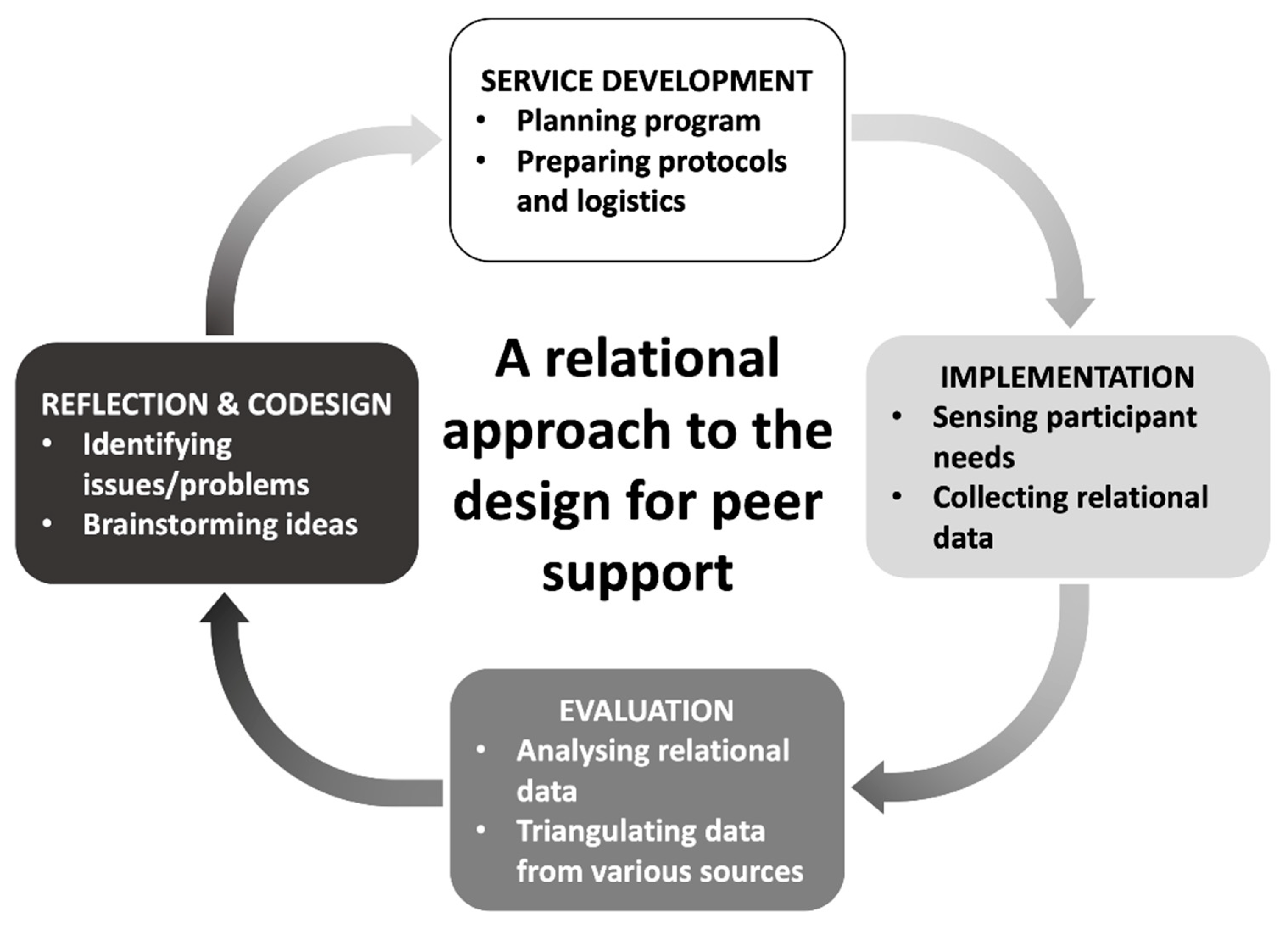

4.2. A Relational Approach

4.2.1. Process

4.2.2. Positioning of the Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Network Analysis Results

| Case | Participant | Tie Strength | Degree Centrality | Reciprocity | Egonet Density | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Support | Affirmative Support | Aid | Outdegree | Indegree | ||||

| Befriending | A | 2.00 | 0.67 | 1.50 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.9 | 1.27 |

| B | 1.41 | 0.42 | 1.25 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 1.40 | ||

| C | 2.75 | 1.83 | 3.00 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.91 | ||

| D | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 1.52 | ||

| E | 1.58 | 1.17 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 1.24 | ||

| F | 2.58 | 1.58 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 1.32 | ||

| G | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 1.45 | ||

| Colourful Youth | A | 1.16 | 1.08 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 1.78 |

| B | 3 | 2.25 | 1.67 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 1.35 | ||

| C | 2.6 | 2.83 | 1.67 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 1.39 | ||

| D | 1.2 | 1 | 1.33 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 1.78 | ||

| E | 0.2 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 1.93 | ||

| F | 1.6 | 2.66 | 1.92 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 1.52 | ||

| G | 1.5 | 1.83 | 1.5 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 1.68 | ||

References

- Bowers, H.; Mordey, M.; Runnicles, D.; Barker, S.; Thomas, N.; Wilkins, A.; Lockwood, S.; Catley, A. Not a One Way Street: Research into Older People’s Experiences of Support Based on Mutuality and Reciprocity; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, H.; Lockwood, S.; Eley, A.; Catley, A.; Runnicles, D.; Mordey, M.; Barker, S.; Thomas, N.; Jones, C.; Dalziel, S. Widening Choices for Older People with High Support Needs; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W.-T.; Norman, I. The effectiveness and active ingredients of mutual support groups for family caregivers of people with psychotic disorders: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1604–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loat, M. Mutual Support and Mental Health: A Route to Recovery; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Maton, K.I. Social support, organizational characteristics, psychological well-being, and group appraisal in three self-help group populations. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1988, 16, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naegele, G.; Schnabel, E.; van de Maat, J.; Kubicki, P.; Chiatti, C.; Rostgaard, T. Measures for Social Inclusion of the Elderly: The Case of Volunteering; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2010.

- Household Projections for Korea 2017-Based: 2017~2047; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Korea, 2019.

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkin, E.A. Vulnerable Populations. In Chronic Illness Care; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.-S.; Hwang, H.-J. A study on the social behavior and social isolation of the elderly Korea. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2015, 11, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.-J. Research of Current State of Abandoned Death in Seoul; Seoul Welfare Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, B.E.; Linden, W.; Najarian, B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 22, 381–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Coad, R. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, A.; Sangiorgi, D. Design for Services; Routledge: Surrey, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla, C. Solutions for relational services. In Service Design with Theory. Discussions on Change, Value and Methods; Lapland University Press (LUP): Rovaniemi, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.S.; Kim, S.; Pahk, Y.; Manzini, E. A sociotechnical framework for the design of collaborative services. Des. Stud. 2018, 55, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TACSI. Love-ins, Lobsters & Racing Cars: Great Living in Late Adulthood; The Australian Centre for Social Innovation: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.B.; Berner, E.S.; Johnson, K.B.; Giuse, D.A.; Murphy, B.A.; Lorenzi, N.M. Recommendations for the design, implementation and evaluation of social support in online communities, networks, and groups. J. Biomed. Inform. 2013, 46, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malz, J.; Dougan, M.; Lin, G. Peer Program Toolkit: Starting, Coordinating and Evaluating Peer Programs at McGill University; Mcgill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australia, C.C. Cancer Support Groups: A Guide to Setting up and Maintaining a Group; Grove, C., Ed.; Cancer Council Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, S.b.S.R. Developing Peer Support in the Community: A Toolkit; Mind: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peer Support Toolkit; DBHIDS: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017.

- Shumaker, S.A.; Brownell, A. Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizzard, J.L.; Klotz, L.E. A framework for sustainable whole systems design. Des. Stud. 2012, 33, 456–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hether, H.J.; Murphy, S.T.; Valente, T.W. A social network analysis of supportive interactions on prenatal sites. Digit. Health 2016, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J.S.; Kahn, R.L.; McLeod, J.D.; Williams, D. Measures and concepts of social support. In Social Support and Health; Cohen, S., Syme, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A. Social networks and health status: Linking theory, research and practice. Patient Couns. Health Educ. 1982, 4, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J. Online supportive interactions: Using a network approach to examine communication patterns within a psychosis social support group in Taiwan. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1504–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronister, J.A.; Johnson, E.K.; Berven, N.L. Measuring social support in rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeslee, J.E. Measuring the support networks of transition-age foster youth: Preliminary validation of a social network assessment for research and practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 52, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbeck, J.S.; Lindsey, A.M.; Carrieri, V.L. The development of an instrument to measure social support. Nurs. Res. 1981, 30, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintz, D.L. Nursing support in labor. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1987, 16, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauls, D.J. Dimensions of professional labor support for intrapartum practice. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2006, 38, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkka, M.T.; Paunonen, M. Social support and its impact on mothers’ experiences of childbirth. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 23, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Social Support, and Women; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, C.C. Using content and network analysis to understand the social support exchange patterns and user behaviors of an online smoking cessation intervention program. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Liebowitz, J. The synergy of social network analysis and knowledge mapping: A case study. Int. J. Manag. Decis. Mak. 2005, 7, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laat, M.; Lally, V.; Lipponen, L.; Simons, R.-J. Investigating patterns of interaction in networked learning and computer-supported collaborative learning: A role for Social Network Analysis. Int. J. Comput. Supported Collab. Learn. 2007, 2, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swert, K.D. Calculating Inter-Coder Reliability in Media Content Analysis Using Krippendorff’s Alpha. Available online: http://www.polcomm.org/wp-content/uploads/ICR01022012.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Narus, J. A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M.; Manschot, M.; De Koning, N. Benefits of co-design in service design projects. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R.; Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupils’ Intellectual Development; Crown House Pub: Bancyfelin, Carmarthen, Wales, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B. Generative tools for co-designing. In Collaborative Design; Scrivener, S.A.R., Ball, L.J., Woodcock, A., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Support Type | Question | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Affective Support | Q1 | How much does this participant make you feel liked or loved? |

| Q2 | How much does this participant make you feel respected or admired? | ||

| Affirmative Support | Q3 | How much can you confide in this participant? | |

| Q4 | How much does this participant agree with or support your actions or thoughts? | ||

| Aid | Q5 | How often does this participant provide you with needed information or advice? | |

| Q6 | If you were confined to bed for several weeks, how often could this participant visit you? | ||

| Qualitative | Q7 | (If you scored any of Qs 1–6 between 0–1) Is there any reason or experience influencing your answer? | |

| Q8 | (If you scored any of Qs 1–6 between 3–4) Is there any reason or experience influencing your answer? | ||

| Q9 | Which type of support do you need most from this service? | ||

| Q10 | What facilitates the construction of supportive relationships with other participants? | ||

| Q11 | What are the barriers to forming supportive relationships with other participants? | ||

| Q12 | How (if at all) can this service be improved? |

| Social Support Domain | Metrics | Operationalization | Application to Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Network size | The number of participants in a support network | N/A |

| Tie strength | The strength of interpersonal ties in a social network [39] as represented by the perceived level of (affective/affirmative/aid) support | All | |

| Structure | Density | The proportion of support relations relative to the total possible number | All |

| Reciprocity | The proportion of reciprocated support relations from the total possible number [25] | All | |

| Degree centrality | The extent to which an individual exchanges support with other individuals in the same network [40] | All | |

| Clique | How larger structures are compounded from smaller ones [37] | All | |

| Quality | Functional content | The functional content of interpersonal relationships [31] | All |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pahk, Y.; Baek, J.S. A Relational Approach to the Design for Peer Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052596

Pahk Y, Baek JS. A Relational Approach to the Design for Peer Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052596

Chicago/Turabian StylePahk, Yoonyee, and Joon Sang Baek. 2021. "A Relational Approach to the Design for Peer Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052596

APA StylePahk, Y., & Baek, J. S. (2021). A Relational Approach to the Design for Peer Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052596