Relationship of Decrease in Frequency of Socialization to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Over after the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

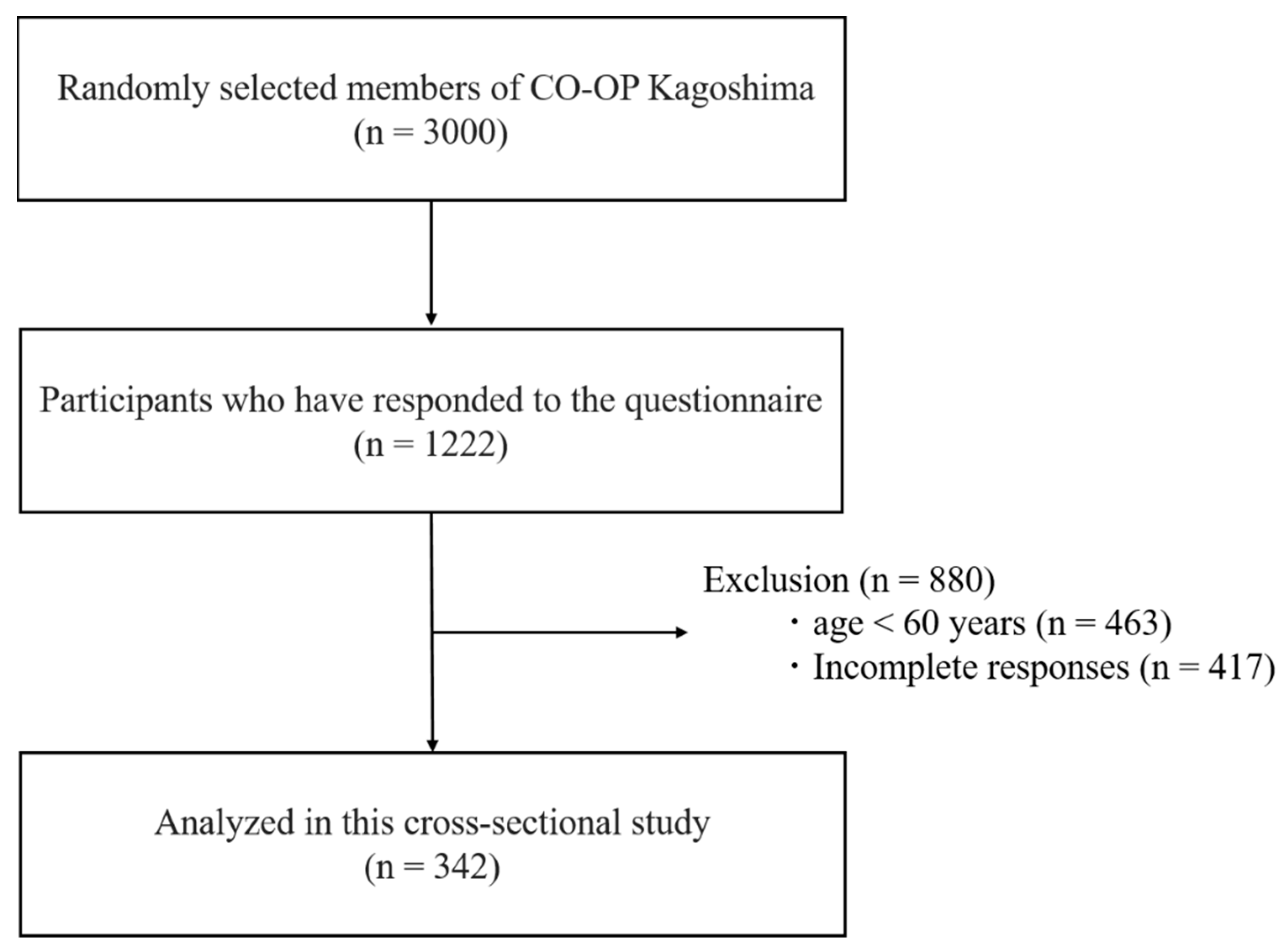

2.3. Participants

2.4. Questionnaire Structure

2.4.1. Social Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

2.4.2. Health History

2.4.3. Daily Life Changes

2.4.4. Social Life Changes

2.4.5. Physical Health Changes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Comparison of Questionnaire Items by Frequency of Socialization

3.3. Relationship of FOS to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Xiang, Z.-C.; Guo, L.; Xu, T.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.-J.; Li, X.-W.; et al. Identification of a Novel Coronavirus Causing Severe Pneumonia in Human: A Descriptive Study. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [COVID-19] Declaration of a State of Emergency in Response to the Novel Coronavirus Disease (April 16) (Ongoing Topics)|Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. Available online: http://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/_00020.html (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- López, J.; Perez-Rojo, G.; Noriega, C.; Carretero, I.; Velasco, C.; Martinez-Huertas, J.A.; López-Frutos, P.; Galarraga, L. Psychological Well-Being among Older Adults during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Comparative Study of the Young-Old and the Old-Old Adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.A.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Newmark, R.L.; Cenzer, I.; Smith, A.K.; Covinsky, K.E.; Escueta, D.P.; Lee, J.M.; Perissinotto, C.M. Social Isolation and Loneliness Among San Francisco Bay Area Older Adults During the COVID-19 Shelter-in-Place Orders. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiot, A.; Pinto, A.J.; Turner, J.E.; Gualano, B. Immunological Implications of Physical Inactivity among Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontology 2020, 66, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Kimura, Y.; Ishiyama, D.; Otobe, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Koyama, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Kusumi, H.; Arai, H. Effect of the COVID-19 Epidemic on Physical Activity in Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Maeda, N.; Hirado, D.; Shirakawa, T.; Urabe, Y. Physical Activity Changes and Its Risk Factors among Community-Dwelling Japanese Older Adults during the COVID-19 Epidemic: Associations with Subjective Well-Being and Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.; Nayak, U.S.; Isaacs, B. The Life-Space Diary: A Measure of Mobility in Old People at Home. Int. Rehabil. Med. 1985, 7, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.S.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Measuring Life-Space Mobility in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1610–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kumagai, S.; Watanabe, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Motohashi, Y.; Shinkai, S. The Frequency of Going Outdoors, and Physical, Psychological and Social Functioning Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi Jpn. J. Public Health 2004, 51, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, A.; Togo, F.; Watanabe, E.; Park, H.; Shephard, R.J.; Aoyagi, Y. Yearlong Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Japanese Adults: The Nakanojo Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2006, 14, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Co-Operative Alliance/ICA. Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Outline. Available online: https://www.kagoshima.coop/about/outline/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Cochran, W.G. Some Methods for Strengthening the Common Χ2 Tests. Biometrics 1954, 10, 417–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the Interpretation of Χ2 from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1922, 85, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Daoust, J.-F. Elderly People and Responses to COVID-19 in 27 Countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashima, R.; Onishi, R.; Saeki, K.; Hirano, M. Perception of COVID-19 Restrictions on Daily Life among Japanese Older Adults: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroi, U. A Study on the Effect of Japanese-Style Lockdown on Self-Restraint Request for COVID-19. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2020, 55, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Lee, S.; Bae, S.; Shinkai, Y.; Chiba, I.; Shimada, H. Relationship between Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Performance and Incidence of Mild Cognitive Impairment among Older Adults: A 48-Month Follow-up Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 88, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, A.; Shiba, K.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I. Can Online Communication Prevent Depression Among Older People? A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Appl. Gerontol. Off. J. South. Gerontol. Soc. 2020, 733464820982147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesnaver, E.; Keller, H.H. Social Influences and Eating Behavior in Later Life: A Review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 30, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendl, A.C.; Perry, B.L. The Impact of Sheltering in Place During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Adults’ Social and Mental Well-Being. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e53–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, M.; Makizako, H.; Ikeda, Y.; Miyata, H.; Nakamura, A.; Han, G.; Shimokihara, S.; Tokuda, K.; Kubozono, T.; Ohishi, M.; et al. Associations between Depressive Symptoms and Satisfaction with Meaningful Activities in Community-Dwelling Japanese Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzoni, R.; Bischoff, S.C.; Breda, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Krznaric, Z.; Nitzan, D.; Pirlich, M.; Singer, P. endorsed by the ESPEN Council ESPEN Expert Statements and Practical Guidance for Nutritional Management of Individuals with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2020, 39, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, H.; Furusawa, Y.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Imai, M.; Kabata, H.; Nishimura, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J. Improving Social Support for Older Adults Through Technology: Findings From the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Santo, S.G.; Franchini, F.; Filiputti, B.; Martone, A.; Sannino, S. The Effects of COVID-19 and Quarantine Measures on the Lifestyles and Mental Health of People Over 60 at Increased Risk of Dementia. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 578628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Mao, L.; Nassis, G.P.; Harmer, P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Li, F. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): The Need to Maintain Regular Physical Activity While Taking Precautions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, R.; Srivastava, V.; Sethi, S. Managing Mental Health Issues among Elderly during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Geriatr. Care Res. 2020, 7, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Y.S.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Shrira, A.; Bodner, E.; Palgi, Y. COVID-19 Health Worries and Anxiety Symptoms among Older Adults: The Moderating Role of Ageism. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriaucioniene, V.; Bagdonaviciene, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Petkeviciene, J. Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall, N = 342 1 | Increased/Unchanged FOS, n = 109 1 | Decreased FOS, n = 233 1 | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.7 (7.2) | 70.2 (7.8) | 68.0 (6.8) | 0.016 a |

| Sex | 0.57 b | |||

| male | 52 (15%) | 18 (17%) | 33 (14%) | |

| female | 290 (85%) | 91 (83%) | 200 (86%) | |

| Family structure | 0.37 b | |||

| living alone | 76 (22%) | 21 (19%) | 55 (22%) | |

| living with family | 266 (78%) | 88 (81%) | 178 (78%) | |

| Height (cm) | 154.7 (10.1) | 154.5 (7.0) | 154.8 (11.3) | 0.8 a |

| Occupation Status | 0.7 c | |||

| unemployed | 7 (2.0%) | 3 (2.8%) | 4 (1.7%) | |

| remunerative employment | 335 (98%) | 106 (97%) | 229 (98%) | |

| Number of underlying diseases | 1.0 (0.0–5.0) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.5 d |

| Daily Life Changes | Overall, N = 342 1 | Increased/Unchanged FOS, n = 109 1 | Decreased FOS, n = 233 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-care and ADL | ||||

| Bathing | 0.033 b | |||

| increased | 10 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (4.3%) * | |

| decreased | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| unchanged | 329 (96%) | 109 (100%) | 220 (94%) * | |

| Hours of sleep | 0.084 a | |||

| longer | 18 (5.3%) | 3 (2.8%) | 15 (6.4%) | |

| shorter | 35 (10%) | 7 (6.4%) | 28 (12%) | |

| unchanged | 289 (85%) | 99 (91%) | 190 (82%) | |

| Bedtime | 0.067 a | |||

| longer | 39 (11%) | 7 (6.4%) | 32 (14%) | |

| shorter | 19 (5.6%) | 4 (3.7%) | 15 (6.4%) | |

| unchanged | 284 (83%) | 98 (90%) | 186 (80%) | |

| Hours of nap | 0.5 a | |||

| longer | 25 (7.3%) | 6 (5.5%) | 19 (8.2%) | |

| shorter | 11 (3.2%) | 2 (1.8%) | 9 (3.9%) | |

| unchanged | 306 (89%) | 101 (93%) | 205 (88%) | |

| Cooking | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 49 (14%) | 3 (2.8%) | 46 (20%) * | |

| decreased | 7 (2.0%) | 3 (2.8%) | 4 (1.7%) * | |

| unchanged | 286 (84%) | 103 (94%) | 183 (79%) ** | |

| The amount of food | 0.4 a | |||

| increased | 29 (8.5%) | 7 (6.4%) | 22 (9.4%) | |

| decreased | 22 (6.4%) | 5 (4.6%) | 17 (7.3%) | |

| unchanged | 291 (85%) | 97 (89%) | 194 (83%) | |

| Time of day to eat | 0.2 b | |||

| longer | 29 (8.5%) | 6 (5.5%) | 23 (9.9%) | |

| shorter | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| unchanged | 310 (91%) | 103 (94%) | 207 (89%) | |

| Urination and defecation | 0.012 b | |||

| increased | 21 (6.1%) | 2 (1.8%) | 19 (8.2%) * | |

| decreased | 6 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2.6%) | |

| unchanged | 315 (92%) | 107 (98%) | 208 (89%) * | |

| IADL | ||||

| Shopping | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| decreased | 168 (49%) | 13 (12%) | 155 (67%) ** | |

| unchanged | 172 (50%) | 96 (88%) | 76 (33%) ** | |

| Cleaning | 0.3 a | |||

| increased | 54 (16%) | 12 (11%) | 42 (18%) | |

| decreased | 17 (5.0%) | 6 (5.5%) | 11 (4.7%) | |

| unchanged | 271 (79%) | 91 (83%) | 180 (77%) | |

| Laundry | 0.12 a | |||

| increased | 43 (13%) | 9 (8.3%) | 34 (15%) | |

| decreased | 9 (2.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (3.4%) | |

| unchanged | 290 (85%) | 99 (91%) | 191 (82%) | |

| Number of phone calls | 0.001 a | |||

| increased | 48 (14%) | 8 (7.3%) | 40 (17%) * | |

| decreased | 31 (9.1%) | 4 (3.7%) | 27 (12%) * | |

| unchanged | 263 (77%) | 97 (89%) | 166 (71%) ** | |

| Hours engaged in phone calls | 0.044 a | |||

| longer | 43 (13%) | 7 (6.4%) | 36 (15%) * | |

| shorter | 13 (3.8%) | 3 (2.8%) | 10 (4.3%) | |

| unchanged | 286 (84%) | 99 (91%) | 187 (80%) * | |

| Amount of trash | 0.023 a | |||

| increased | 54 (16%) | 9 (8.3%) | 45 (19%) * | |

| decreased | 32 (9.4%) | 9 (8.3%) | 23 (9.9%) | |

| unchanged | 256 (75%) | 91 (83%) | 165 (71%) ** | |

| Missing medicine | 0.8 b | |||

| increased | 14 (4.1%) | 3 (2.8%) | 11 (4.7%) | |

| decreased | 9 (2.6%) | 3 (2.8%) | 6 (2.6%) | |

| unchanged | 319 (93%) | 103 (94%) | 216 (93%) |

| Social Life Changes | Overall, N = 342 1 | Increased/Unchanged FOS, n = 109 1 | Decreased FOS, n = 233 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work and Hobbies | ||||

| Time spent on hobbies and interests | <0.001 a | |||

| increased | 38 (11%) | 4 (3.7%) | 34 (15%) ** | |

| decreased | 161 (47%) | 38 (35%) | 123 (53%) ** | |

| unchanged | 143 (42%) | 67 (61%) | 76 (33%) ** | |

| Roles and tasks at home | 0.016 a | |||

| increased | 33 (9.6%) | 5 (4.6%) | 28 (12%) * | |

| decreased | 46 (13%) | 10 (9.2%) | 36 (15%) | |

| unchanged | 263 (77%) | 94 (86%) | 169 (73%) ** | |

| Commuting to work | 0.045 a | |||

| increased | 10 (2.9%) | 3 (2.8%) | 7 (3.0%) | |

| decreased | 78 (23%) | 16 (15%) | 62 (27%) * | |

| unchanged | 254 (74%) | 90 (83%) | 164 (70%) * | |

| Leisure | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 5 (1.5%) | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | |

| decreased | 281 (82%) | 72 (66%) | 209 (90%) ** | |

| unchanged | 56 (16%) | 36 (33%) | 20 (8.6%) ** | |

| Interpersonal Interaction | ||||

| Opportunity to meet with friends and neighbors | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 3 (0.9%) | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| decreased | 244 (71%) | 52 (48%) | 192 (82%) ** | |

| unchanged | 95 (28%) | 55 (50%) | 40 (17%) ** | |

| Time to talk to friends and neighbors | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| decreased | 238 (70%) | 53 (49%) | 185 (79%) ** | |

| unchanged | 102 (30%) | 55 (50%) | 47 (20%) ** | |

| Gatherings | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| decreased | 222 (65%) | 55 (50%) | 167 (72%) ** | |

| unchanged | 119 (35%) | 53 (49%) | 66 (28%) ** | |

| Family communication | <0.001 a | |||

| increased | 21 (6.1%) | 3 (2.8%) | 18 (7.7%) | |

| decreased | 128 (37%) | 22 (20%) | 106 (45%) | |

| unchanged | 193 (56%) | 84 (77%) | 109 (47%) | |

| Eating out | <0.001 b | |||

| increased | 4 (1.2%) | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (0.4%) * | |

| decreased | 279 (82%) | 65 (60%) | 214 (92%) ** | |

| unchanged | 59 (17%) | 41 (38%) | 18 (7.7%) ** | |

| Communication via the Internet | <0.001 a | |||

| increased | 90 (26%) | 21 (19%) | 69 (30%) * | |

| decreased | 80 (23%) | 15 (14%) | 65 (28%) ** | |

| unchanged | 172 (50%) | 73 (67%) | 99 (42%) ** |

| Frequency of Socialization | Overall, N = 342 1 | Increased/Unchanged FOS, n = 109 1 | Decreased FOS, n = 233 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health Changes | ||||

| Weight | 0.010 a | |||

| gained | 74 (22%) | 13 (12%) | 61 (26%) ** | |

| lost | 29 (8.5%) | 9 (8.3%) | 20 (8.6%) | |

| unchanged | 239 (70%) | 87 (80%) | 152 (65%) ** | |

| Physical activity | 0.002 a | |||

| increased | 17 (5.0%) | 7 (6.4%) | 10 (4.3%) | |

| decreased | 106 (31%) | 20 (18%) | 86 (37%) ** | |

| unchanged | 219 (64%) | 82 (75%) | 137 (59%) ** | |

| Uncomfortable with own body | 0.4 a | |||

| yes | 87 (25%) | 24 (22%) | 63 (27%) | |

| no | 255 (75%) | 85 (78%) | 170 (73%) |

| Crude Model | Adjusted Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Daily Life Changes | ||||||||

| Bathing | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 11.6 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 9.6 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 2.9 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.1 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Cooking | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 4.28 | 0.56 | 32.71 | 0.16 | 3.99 | 0.52 | 30.40 | 0.18 |

| decreased | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.02 |

| Urination and defecation | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 1.22 | 0.12 | 12.00 | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.11 | 9.14 | 1.00 |

| decreased | 3.4 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.1 ×107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Shopping | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 12.8 × 108 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 13.6 × 108 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 17.48 | 6.81 | 44.90 | <0.01 | 18.76 | 7.12 | 49.41 | <0.01 |

| Number of phone calls | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.69 | 0.15 | 3.12 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 3.27 | 0.67 |

| decreased | 1.53 | 0.32 | 7.32 | 0.60 | 1.61 | 0.32 | 8.21 | 0.57 |

| Hours engaged in phone calls | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| longer | 1.33 | 0.23 | 7.71 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.19 | 6.86 | 0.89 |

| shorter | 0.56 | 0.09 | 3.63 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 3.74 | 0.49 |

| Amount of trash | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.51 | 0.15 | 1.73 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 1.66 | 0.26 |

| decreased | 0.33 | 0.08 | 1.34 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 1.14 | 0.08 |

| Social Life Changes | ||||||||

| Meet with friends and neighbors | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 1.92 | 0.62 | 5.96 | 0.26 | 1.83 | 0.58 | 5.80 | 0.30 |

| Time to talk to friends and neighbors | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 12.8 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 8.0 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 0.90 | 0.30 | 2.73 | 0.85 | 1.05 | 0.33 | 3.30 | 0.93 |

| Time spent on hobbies and interests | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 1.53 | 0.32 | 7.37 | 0.60 | 1.52 | 0.30 | 7.81 | 0.61 |

| decreased | 1.40 | 0.67 | 2.90 | 0.37 | 1.35 | 0.63 | 2.89 | 0.44 |

| Roles and tasks at home | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.84 | 0.20 | 3.57 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 3.20 | 0.67 |

| decreased | 1.04 | 0.32 | 3.39 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.31 | 3.47 | 0.95 |

| Gatherings | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.00 | 0.00 | . | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| decreased | 1.06 | 0.49 | 2.30 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.48 | 2.35 | 0.87 |

| Family communication | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 5.24 | 0.55 | 50.08 | 0.15 | 5.52 | 0.52 | 58.19 | 0.16 |

| decreased | 2.27 | 1.02 | 5.04 | 0.04 | 2.18 | 0.97 | 4.93 | 0.06 |

| Eating out | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 3.21 | 1.11 | 9.26 | 0.03 | 3.47 | 1.21 | 9.97 | 0.02 |

| Leisure | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 6.5 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.6 × 107 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| decreased | 0.77 | 0.25 | 2.32 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 2.57 | 0.70 |

| Communication via the Internet | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 1.99 | 0.84 | 4.69 | 0.12 | 2.11 | 0.86 | 5.16 | 0.10 |

| decreased | 1.60 | 0.62 | 4.11 | 0.33 | 1.57 | 0.60 | 4.14 | 0.36 |

| Commuting to work | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.21 | 0.01 | 3.78 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 5.24 | 0.38 |

| decreased | 0.61 | 0.22 | 1.68 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 1.77 | 0.37 |

| Physical Health Changes | ||||||||

| Weight | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| gained | 1.18 | 0.42 | 3.26 | 0.75 | 1.11 | 0.39 | 3.15 | 0.84 |

| lost | 0.73 | 0.22 | 2.41 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.21 | 2.46 | 0.61 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| unchanged a | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| increased | 0.19 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 1.06 | 0.06 |

| decreased | 1.10 | 0.43 | 2.78 | 0.84 | 1.10 | 0.42 | 2.88 | 0.84 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimokihara, S.; Maruta, M.; Hidaka, Y.; Akasaki, Y.; Tokuda, K.; Han, G.; Ikeda, Y.; Tabira, T. Relationship of Decrease in Frequency of Socialization to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Over after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052573

Shimokihara S, Maruta M, Hidaka Y, Akasaki Y, Tokuda K, Han G, Ikeda Y, Tabira T. Relationship of Decrease in Frequency of Socialization to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Over after the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052573

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimokihara, Suguru, Michio Maruta, Yuma Hidaka, Yoshihiko Akasaki, Keiichiro Tokuda, Gwanghee Han, Yuriko Ikeda, and Takayuki Tabira. 2021. "Relationship of Decrease in Frequency of Socialization to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Over after the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052573

APA StyleShimokihara, S., Maruta, M., Hidaka, Y., Akasaki, Y., Tokuda, K., Han, G., Ikeda, Y., & Tabira, T. (2021). Relationship of Decrease in Frequency of Socialization to Daily Life, Social Life, and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Over after the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052573