The Relationship between Social Anxiety, Smartphone Use, Dispositional Trust, and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

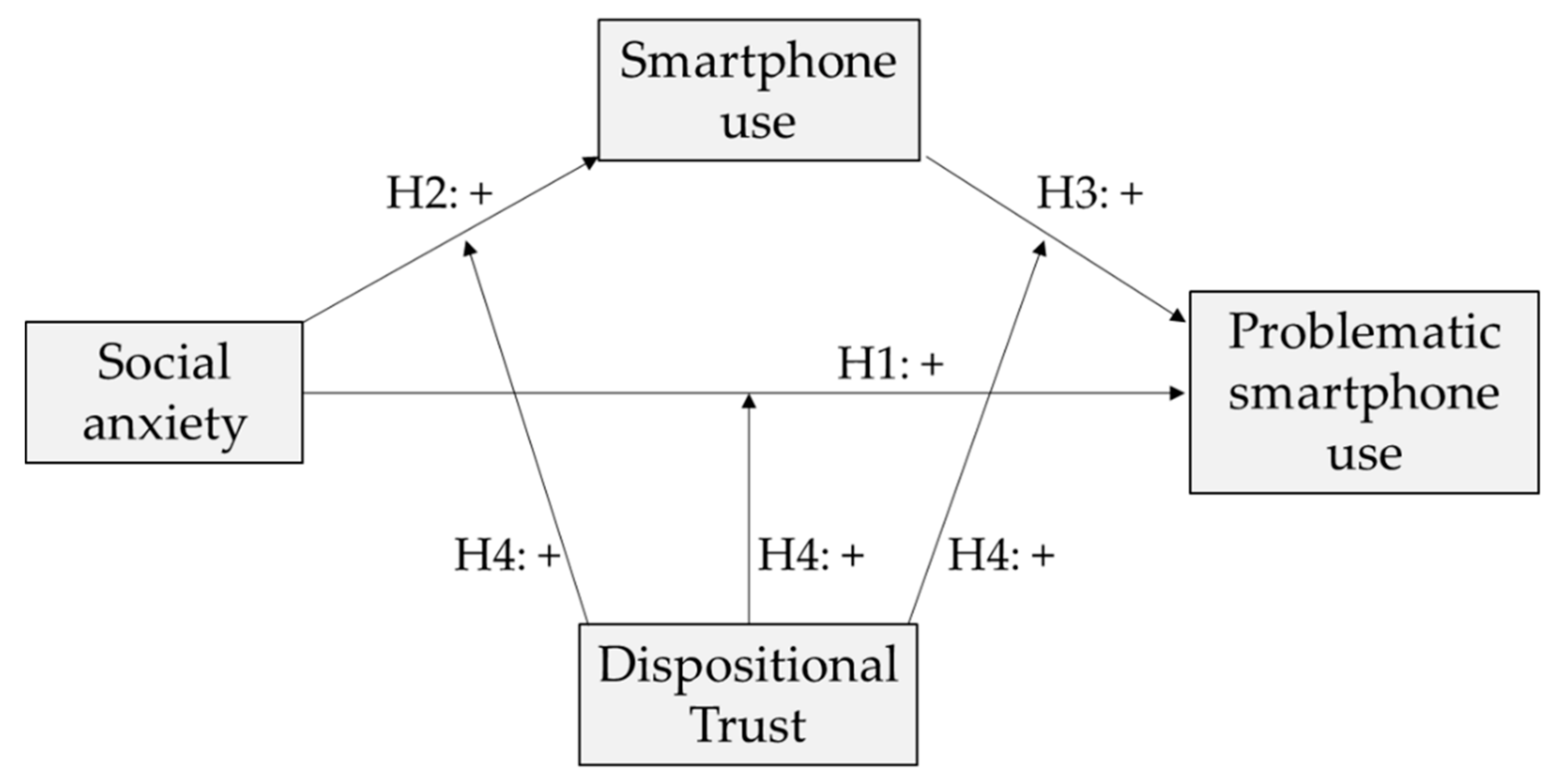

1.1. Social Anxiety and Problematic Smartphone Use

1.2. The Mediating Role of Smartphone Use

1.3. The Moderating Role of Dispositional Trust

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytical Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

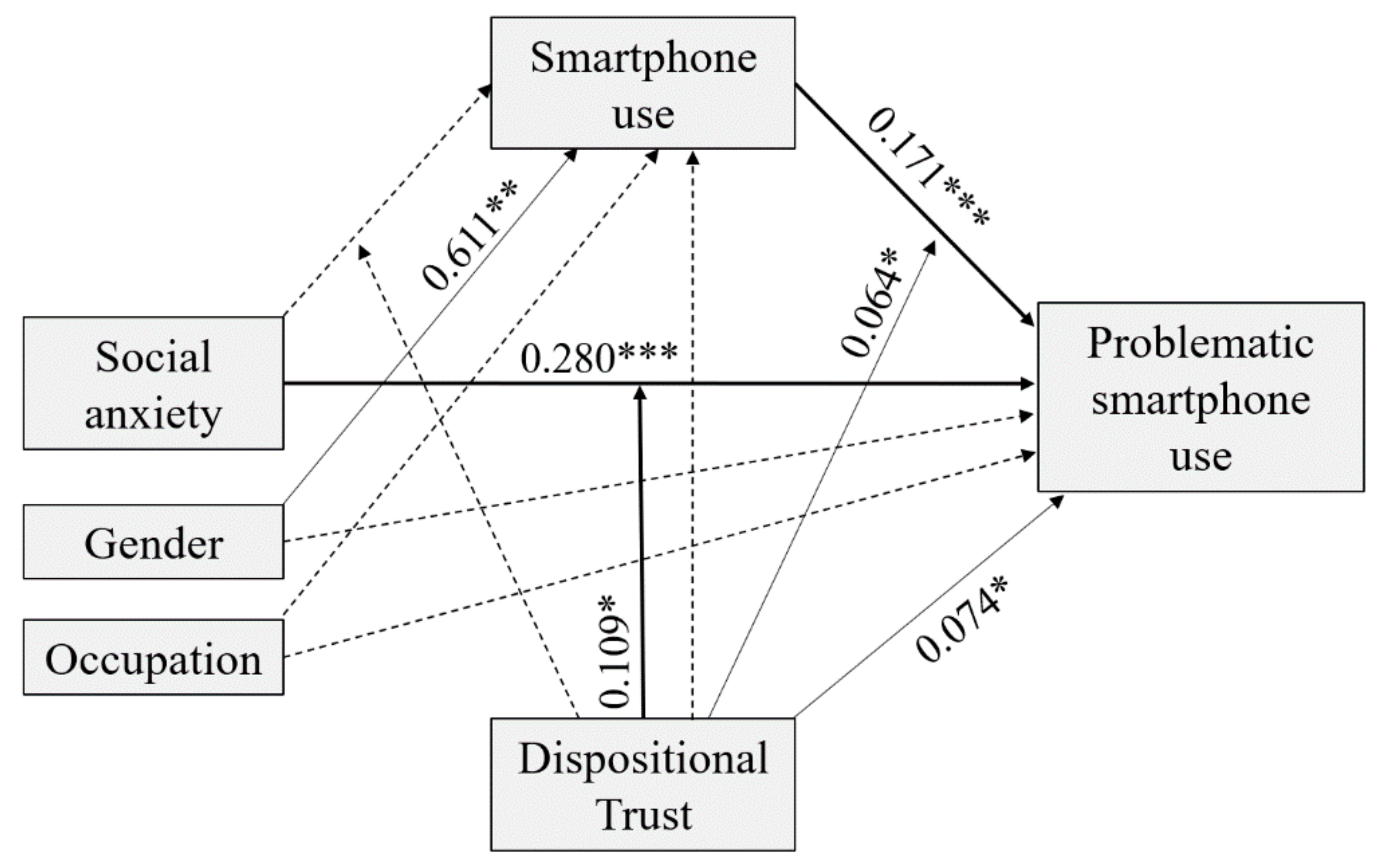

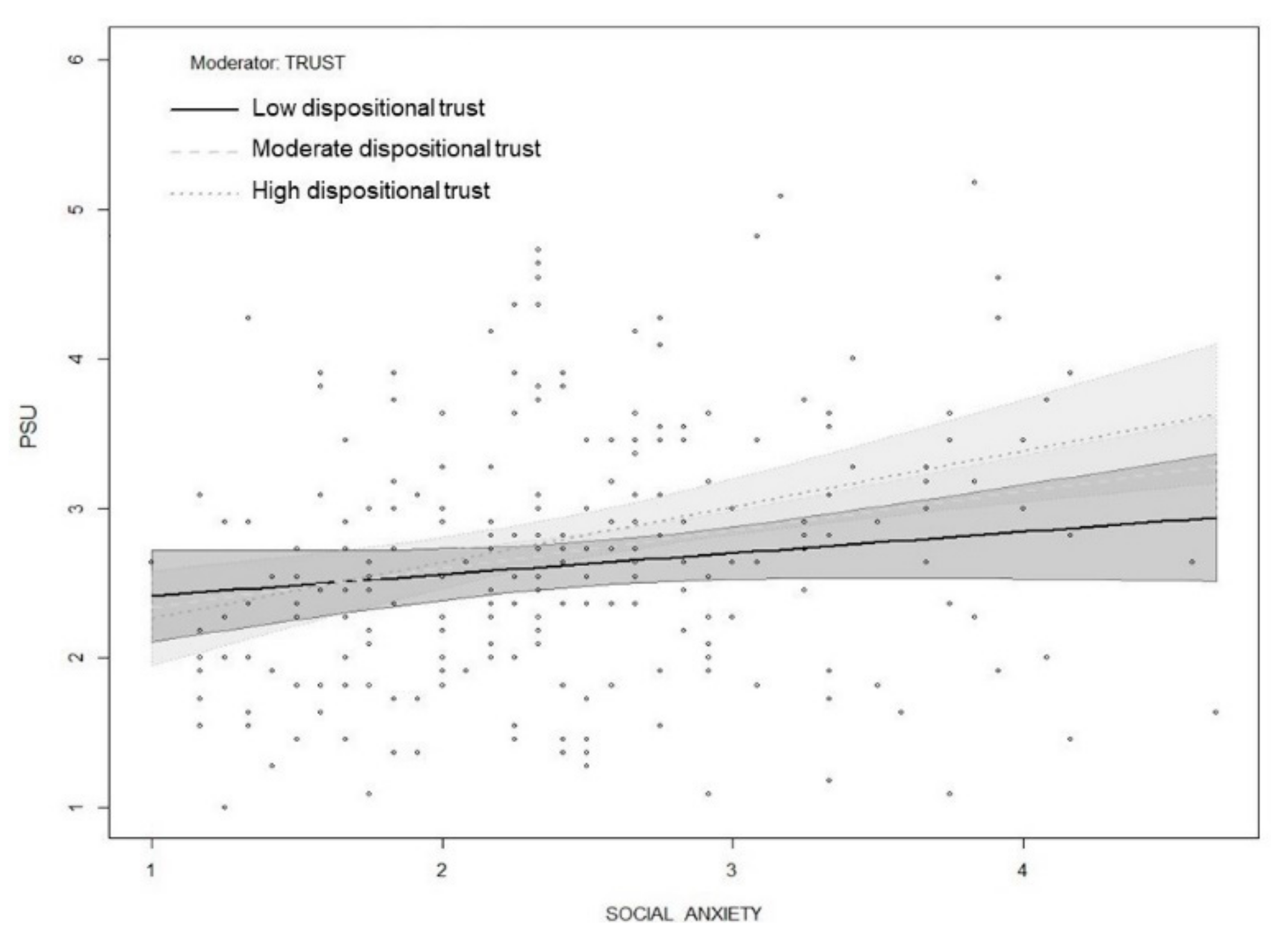

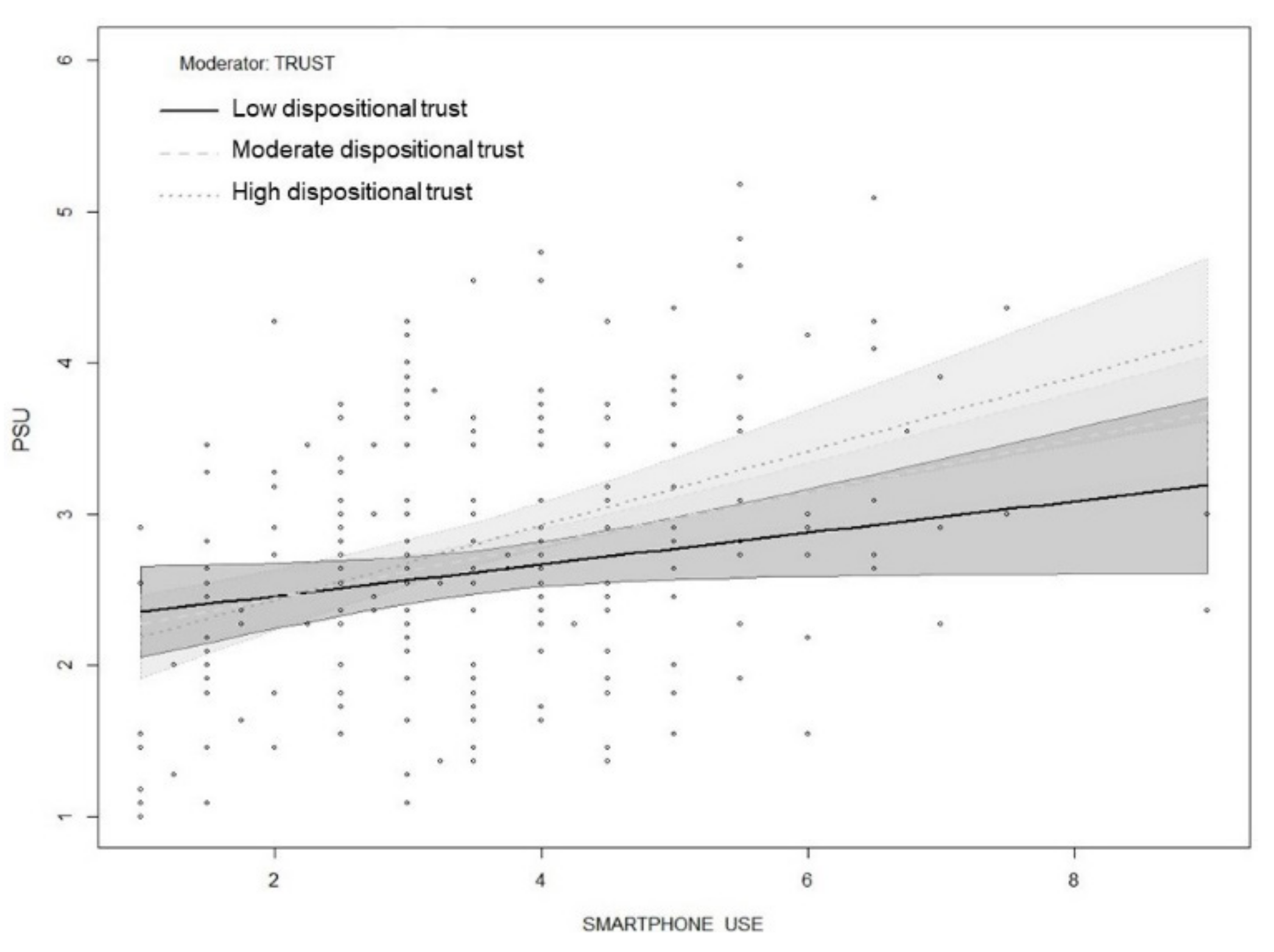

3.2. Primary Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.A.; Steiner, G.Z.; Smith, L.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Gleeson, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Armitage, C.J.; et al. The “online brain”: How the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L. Sedated by the Screen: Social Use of Time in the Age of Mediated Acceleration. Available online: www.igi-global.com/chapter/sedated-by-the-screen/223051 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Brackebush, J. How Mobile Is Overtaking Desktop for Global Media Consumption, in 5 Charts; Digiday: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, M.; Brenner, J. The Demographics of Social Media Users—2012; Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, A.L.; Juckes, S.C.; White, K.M.; Walsh, S.P. Personality and Self-Esteem as Predictors of Young People’s Technology Use. CyberPsychology Behav. 2008, 11, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Chang, C.-T.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, Z.-H. The dark side of smartphone usage: Psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Wang, H.-Z.; Gaskin, J.; Wang, L.-H. The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018; Pew Research Center, Internet, Science & Tech: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly around the World, but Not Always Equally; Pew Research Center, Internet, Science & Tech: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brunborg, G.S.; Mentzoni, R.A.; Molde, H.; Myrseth, H.; Skouverøe, K.J.M.; Bjorvatn, B.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between media use in the bedroom, sleep habits and symptoms of insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 2011, 20, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanaj, K.; Johnson, R.E.; Barnes, C.M. Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2014, 124, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumosleh, J.M.; Jaalouk, D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students—A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panova, T.; Carbonell, X.; Chamarro, A.; Puerta-Cortés, D.X. Specific smartphone uses and how they relate to anxiety and depression in university students: A cross-cultural perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawi, N.S.; Samaha, M. To excel or not to excel: Strong evidence on the adverse effect of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Comput. Educ. 2016, 98, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J.; Shin, S. A Comparative Study Of Smartphone Addiction Drivers’ Effect on Work Performance in the U.S. and Korea. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2016, 32, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xiong, D.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V. Is Internet addiction a useful concept? Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Chung, S.J.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.; Kwon, J.-G.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, D.; Choi, J.-S. Investigation of Correlated Internet and Smartphone Addiction in Adolescents: Copula Regression Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Wegmann, E.; Sariyska, R.; Demetrovics, Z.; Brand, M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of Internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.; Black, D.W. Internet Addiction. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Chang, L.-R.; Tseng, H.-W.; Yen, L.-Y.; Yang, C.C.; Kuo, T.B. Time distortion associated with smartphone addiction: Identifying smartphone addiction via a mobile application (App). J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 65, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Won, W.-Y.; Park, J.-W.; Min, J.-A.; Hahn, C.; Gu, X.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, D.-J. Development and Validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chiang, C.-L.; Lin, P.-H.; Chang, L.-R.; Ko, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lin, S.-H. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Smartphone Addiction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Müller, A.; Wölfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wölfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehroof, M.; Griffiths, M.D. Online Gaming Addiction: The Role of Sensation Seeking, Self-Control, Neuroticism, Aggression, State Anxiety, and Trait Anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: A review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 62, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedi, Z.; Saiphoo, A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Stress Health 2018, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L.; Camerini, A.-L.; Schulz, P.J. Neuroticism in the digital age: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Discriminant Validity of NEO-PIR Facet Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992, 52, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Heimberg, R.G. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Spence, S.H. The etiology of social phobia: Empirical evidence and an initial model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 24, 737–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R. Social Anxiety, Shyness, and Related Constructs. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 161–194. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas-Ferrari, M.C.; Hallak, J.E.; Trzesniak, C.; Filho, A.S.; Machado-De-Sousa, J.P.; Chagas, M.H.N.; Nardi, A.E.; Crippa, J.A.S. Neuroimaging in social anxiety disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 34, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneier, F.R.; Blanco, C.; Antia, S.X.; Liebowitz, M.R. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 25, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurr, J.M.; Stopa, L. The observer perspective: Effects on social anxiety and performance. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.J.; Reid, F.J. Text or Talk? Social Anxiety, Loneliness, and Divergent Preferences for Cell Phone Use. CyberPsychology Behav. 2007, 10, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.L.; Steen, E.; Stavropoulos, V. Internet use and Problematic Internet Use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Orue, I.; Smith, P.K.; Calvete, E. Longitudinal and Reciprocal Relations of Cyberbullying with Depression, Substance Use, and Problematic Internet Use among Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J.; Philippot, P.; Schmid, C.; Maurage, P.; De Mol, J.; Van Der Linden, M. Is Dysfunctional Use of the Mobile Phone a Behavioural Addiction? Confronting Symptom-Based versus Process-Based Approaches. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 22, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljomaa, S.S.; Al Qudah, M.F.; Albursan, I.S.; Bakhiet, S.F.; Abduljabbar, A.S. Smartphone addiction among university students in the light of some variables. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.D.-S.; De Fonseca, F.R.; Rubio, G. Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçearslan, Ş.; Mumcu, F.K.; Haşlaman, T.; Çevik, Y.D. Modelling smartphone addiction: The role of smartphone usage, self-regulation, general self-efficacy and cyberloafing in university students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, A.L.; Marciano, L. The Longitudinal Relationship between Smartphone Use, Smartphone Addiction and Depression in Adolescents: An Application of the RI-CLPM. In Proceedings of the 69th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association (ICA), Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, S.; Castro, R.P.; Kwon, M.; Filler, A.; Kowatsch, T.; Schaub, M.P. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cougle, J.R.; Fitch, K.E.; Fincham, F.D.; Riccardi, C.J.; Keough, M.E.; Timpano, K.R. Excessive reassurance seeking and anxiety pathology: Tests of incremental associations and directionality. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.W.; Stapinski, L.A. Seeking safety on the internet: Relationship between social anxiety and problematic internet use. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Tiamiyu, M.; Weeks, J. Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madell, D.E.; Muncer, S.J. Control over Social Interactions: An Important Reason for Young People’s Use of the Internet and Mobile Phones for Communication? CyberPsychology Behav. 2007, 10, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.H.; Chin, B.; Park, D.-H.; Ryu, S.-H.; Yu, J. Characteristics of Excessive Cellular Phone Use in Korean Adolescents. CyberPsychology Behav. 2008, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, A.C.; Fernandez, K.C.; Levinson, C.A.; Augustine, A.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Rodebaugh, T.L. Compensatory internet use among individuals higher in social anxiety and its implications for well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, S.E. Relations Among Loneliness, Social Anxiety, and Problematic Internet Use. CyberPsychology Behav. 2007, 10, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomée, S.; Härenstam, A.; Hagberg, M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults—A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prizant-Passal, S.; Shechner, T.; Aderka, I.M. Social anxiety and internet use—A meta-analysis: What do we know? What are we missing? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, K.; Akgönül, M.; Akpinar, A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, U.; Çolak, T.S. Self-concealment, Social Network Sites Usage, Social Appearance Anxiety, Loneliness of High School Students: A Model Testing. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2016, 4, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka-Bonetta, J.; Sindermann, C.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. Personality Associations With Smartphone and Internet Use Disorder: A Comparison Study Including Links to Impulsivity and Social Anxiety. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chang, L.-R.; Lee, Y.-H.; Tseng, H.-W.; Kuo, T.B.J.; Chen, S.-H. Development and Validation of the Smartphone Addiction Inventory (SPAI). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, A.; Eijnden, R.V.D.; Garretsen, H. ’Internet addiction’—A call for systematic research. J. Subst. Use 2001, 6, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Pan, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-H. Smartphone gaming and frequent use pattern associated with smartphone addiction. Medicine 2016, 95, e4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression, anxiety and problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.A.; Davidson, B.I.; Shaw, H.; Geyer, K. Do smartphone usage scales predict behavior? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2019, 130, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J.; Elhai, J.D. The association between problematic smartphone use, depression and anxiety symptom severity, and objectively measured smartphone use over one week. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.A. Foundations of interpersonal trust. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 587–607. ISBN 978-1-57230-918-0. [Google Scholar]

- Haselhuhn, M.P.; Kennedy, J.A.; Kray, L.J.; Van Zant, A.B.; Schweitzer, M.E. Gender differences in trust dynamics: Women trust more than men following a trust violation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 56, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.; Hiltz, S.R.; Passerini, K. Trust and Privacy Concern within Social Networking Sites. A Comparison of Facebook and MySpace. In Proceedings of the 13th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2007, Keystone, CO, USA, 9–12 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledgianowski, D.; Kulviwat, S. Using Social Network Sites: The Effects of Playfulness, Critical Mass and Trust in a Hedonic Context. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2009, 49, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Fu, S.; de Vreede, G.-J. Understanding trust influencing factors in social media communication: A qualitative study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, P.R. Social presence. In Social Computing: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M.H.; Wood, J.V.; Holmes, J.G. Dispositional pathways to trust: Self-esteem and agreeableness interact to predict trust and negative emotional disclosure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 113, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M.J. Privacy, Trust, and Disclosure: Exploring Barriers to Electronic Commerce. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, C.; Ellis, S. Understanding Self-Disclosure in Electronic Communities: An Exploratory Model of Privacy Risk Beliefs, Reciprocity, and Trust. In Proceedings of the 13th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2007, Keystone, CO, USA, 9–12 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Usta, E.; Korkmaz, Ö.; Kurt, I. The examination of individuals’ virtual loneliness states in Internet addiction and virtual environments in terms of inter-personal trust levels. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S.; Park, N.; Kee, K.F. Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students’ Life Satisfaction, Trust, and Participation. J. Comput. Commun. 2009, 14, 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; LaRose, R.; Peng, W. Loneliness as the Cause and the Effect of Problematic Internet Use: The Relationship between Internet Use and Psychological Well-Being. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Fan, W.; Gordon, M. The joint moderating role of trust propensity and gender on consumers’ online shopping behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi, S.; Marciano, L.; Annoni, A.M.; Camerini, A.-L. “What you say and how you say it” matters: An experimental evidence of the role of synchronicity, modality, and message valence during smartphone-mediated communication. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, C.; Sciacca, F.; Hichy, Z. Italian Validation of Smartphone Addiction Scale Short Version for Adolescents and Young Adults (SAS-SV). Psychology 2017, 8, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.; Phillips, J.G. Personality and self reported mobile phone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireku, M.O.; Mueller, W.; Fleming, C.; Chang, I.; Dumontheil, I.; Thomas, M.S.; Eeftens, M.; Elliott, P.; Röösli, M.; Toledano, M.B. Total recall in the SCAMP cohort: Validation of self-reported mobile phone use in the smartphone era. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelemans, S.A.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Branje, S.J.T.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Colpin, H.; Verschueren, K.; Goossens, L. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) Short Form: Longitudinal Measurement Invariance in Two Community Samples of Youth. Assessment 2019, 26, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inderbitzen-Nolan, H.M.; Walters, K.S. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents: Normative Data and Further Evidence of Construct Validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2000, 29, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch, E.A.; Masia-Warner, C.; Dent, H.C.; Roberti, J.W.; Fisher, P.H. Psychometric evaluation of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents and the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children: Construct validity and normative data. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K.; Gustafson, D.H. Perceived Helpfulness of Physicians’ Communication Behavior and Breast Cancer Patients’ Level of Trust over Time. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 24, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, E.C.; Brockner, J. In the eyes of the beholder? The role of dispositional trust in judgments of procedural and interactional fairness. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 118, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Darcin, A.E.; Kose, S.; Noyan, C.O.; Nurmedov, S.; Yılmaz, O.; Dilbaz, N. Smartphone addiction and its relationship with social anxiety and loneliness. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitborde, N.J.K.; Srihari, V.H.; Pollard, J.M.; Addington, D.N.; Woods, S.W. Mediators and moderators in early intervention research. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2010, 4, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whisman, M.A.; McClelland, G.H. Designing, Testing, and Interpreting Interactions and Moderator Effects in Family Research. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.E.; Grothendieck, G. Rockchalk: Regression Estimation and Presentation. 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rockchalk/rockchalk.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10th ed.; Allyn & Bacon, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-205-75561-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Namazi, M.; Namazi, N.-R. Conceptual Analysis of Moderator and Mediator Variables in Business Research. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 36, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Wang, Y.; Oh, J. Digital Media Use and Social Engagement: How Social Media and Smartphone Use Influence Social Activities of College Students. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Velthoven, M.H.; Powell, J.; Powell, G. Problematic smartphone use: Digital approaches to an emerging public health problem. Digit. Health 2018, 4, 2055207618759167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgeman, L.; Hefner, I.; Bazon, M.; Yehoshua, O.; Weinstein, A. Studies on the Relationship between Social Anxiety and Excessive Smartphone Use and on the Effects of Abstinence and Sensation Seeking on Excessive Smartphone Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, B.; Turk, C.L.; Heimberg, R.G.; Fresco, D.M.; Hantula, D. The Internet: Home to a severe population of individuals with social anxiety disorder? J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Gallinari, E.F.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Yang, H. Depression, anxiety and fear of missing out as correlates of social, non-social and problematic smartphone use. Addict. Behav. 2020, 105, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Elhai, J.D.; Täht, K.; Vassil, K.; Levine, J.C.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Non-social smartphone use mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: Evidence from a repeated-measures study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L.; Camerini, A.L. Predicting Problematic Smartphone Use from Digital Trace Data and Time Distortion in Adolescents. In Proceedings of the 70th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association (ICA), Gold Coast, Australia, 21–25 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg, K.J.; Boulton, M.J.; Fox, C.L. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Relations among Children’s Trust Beliefs, Psychological Maladjustment and Social Relationships: Are Very High as Well as Very Low Trusting Children at Risk? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, L.R.; Rotenberg, K.J.; Petrocchi, S.; Lecciso, F.; Sakai, A.; Maeshiro, K.; Judson, H. An investigation of children’s peer trust across culture: Is the composition of peer trust universal? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2013, 38, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg, K.J.; Petrocchi, S.; Lecciso, F.; Marchetti, A. The Relation Between Children’s Trust Beliefs and Theory of Mind Abilities. Infant Child Dev. 2015, 24, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, D.; Dietz, G.; Weibel, A. The dark side of trust: When trust becomes a ‘poisoned chalice’. Organization 2013, 21, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.; Ellis, D.A.; Shaw, H.; Piwek, L. Beyond Self-Report: Tools to Compare Estimated and Real-World Smartphone Use. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boase, J.; Ling, R. Measuring Mobile Phone Use: Self-Report versus Log Data. J. Comput. Commun. 2013, 18, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.J. Neural and psychological mechanisms underlying compulsive drug seeking habits and drug memories—indications for novel treatments of addiction. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 40, 2163–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Drug Addiction: Updating Actions to Habits to Compulsions Ten Years on. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Kacmar, C.J.; Choudhury, V. Dispositional Trust and Distrust Distinctions in Predicting High- and Low-Risk Internet Expert Advice Site Perceptions. e-Serv. J. 2004, 3, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | M (SD) | α/r | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social anxiety | 2.45 (0.75) | 0.891 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Dispositional trust | 4.17 (1.34) | - | −0.034 | 1 | |||

| 3. Smartphone use | 3.54 (1.55) | 0.572 | −0.046 | −0.030 | 1 | ||

| 4. Problematic smartphone use (PSU) | 2.71 (0.85) | 0.822 | 0.218 ** | 0.101 | 0.329 *** | 1 | |

| 5. Gender a | - | 0.134 * | −0.047 | 0.187 ** | 0.121 | 1 | |

| 6. Occupation a | - | 0.106 | −0.083 | −0.007 | −0.045 | 0.095 |

| Predictors | Smartphone Use | Problematic Smartphone Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | [95% CI] | B | SE | [95% CI] | |

| Constant | −0.890 | 0.446 | [−1.77; −0.12] | 2.782 *** | 0.225 | [2.34; 3.22] |

| Gender | 0.611 ** | 0.201 | [0.22;1.01] | 0.066 | 0.102 | [−0.13; 0.27] |

| Occupation | 0.017 | 0.207 | [−0.43; 0.39] | −0.099 | 0.104 | [−0.30; 0.11] |

| Social anxiety | −0.152 | 0.134 | [−0.42; 0.11] | 0.280 *** | 0.067 | [0.15; 0.41] |

| Dispositional trust | −0.028 | 0.075 | [−0.17; 0.12] | 0.074 * | 0.037 | [0.00; 0.15] |

| Dispositional trust + Social anxiety | −0.033 | 0.091 | [−0.21; 0.15] | 0.109 * | 0.046 | [0.02; 0.20] |

| Smartphone use | 0.177 *** | 0.033 | [0.11; 0.24] | |||

| Dispositional trust + Smartphone use | 0.064 ** | 0.028 | [0.01; 0.12] | |||

| F | (5, 234) = 2.02 | (7, 232) = 9.00 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.21 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Annoni, A.M.; Petrocchi, S.; Camerini, A.-L.; Marciano, L. The Relationship between Social Anxiety, Smartphone Use, Dispositional Trust, and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052452

Annoni AM, Petrocchi S, Camerini A-L, Marciano L. The Relationship between Social Anxiety, Smartphone Use, Dispositional Trust, and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052452

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnnoni, Anna Maria, Serena Petrocchi, Anne-Linda Camerini, and Laura Marciano. 2021. "The Relationship between Social Anxiety, Smartphone Use, Dispositional Trust, and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052452

APA StyleAnnoni, A. M., Petrocchi, S., Camerini, A.-L., & Marciano, L. (2021). The Relationship between Social Anxiety, Smartphone Use, Dispositional Trust, and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052452