The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

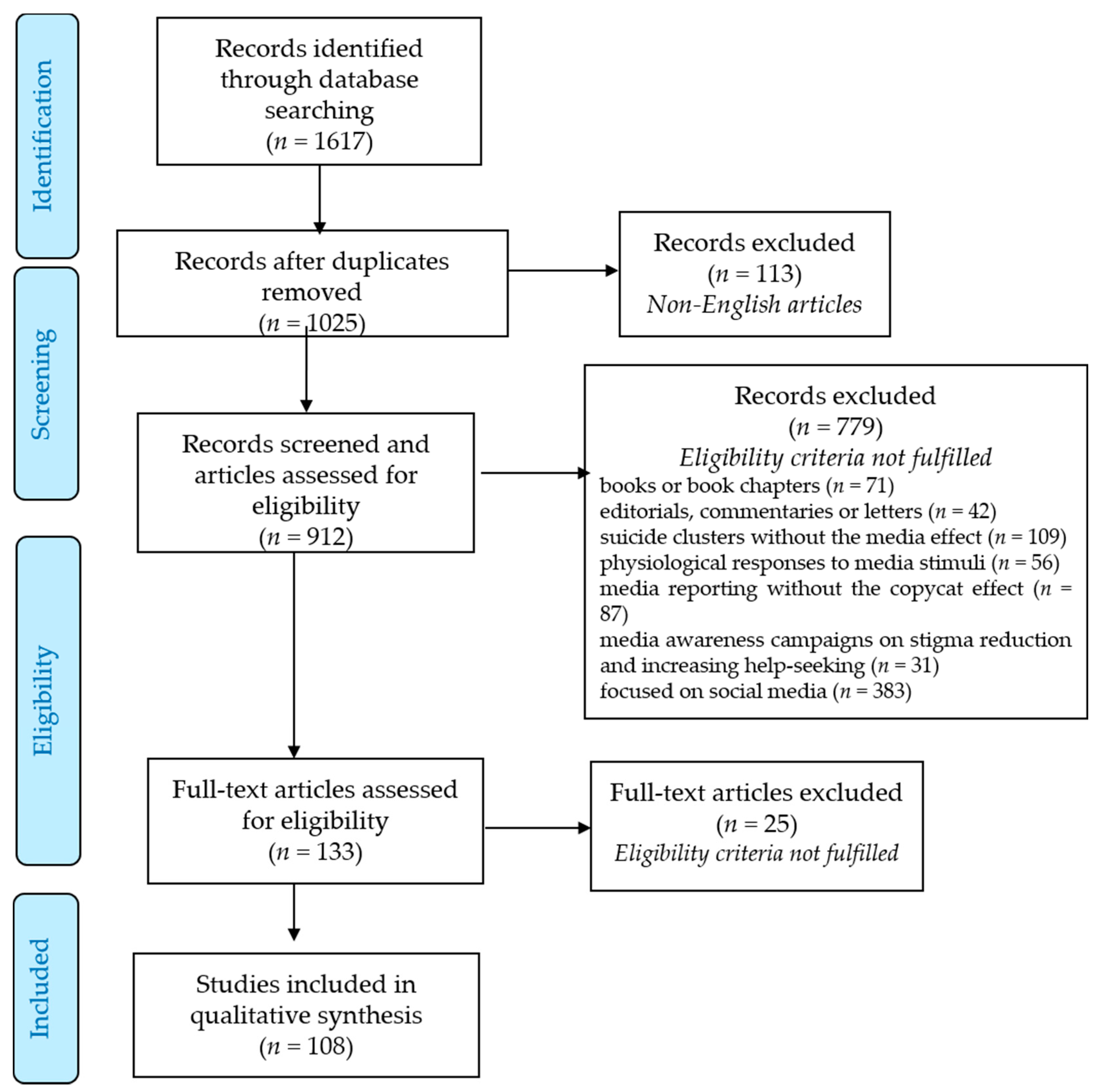

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. The Werther Effect

3.2. The Papageno Effect

3.3. The ‘No Effect’

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326948 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Phillips, D.P. The influence of suggestion on suicide: Substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, E.C., Jr. Confidential death to prevent suicidal contagion: An accepted, but never implemented, nineteenth-century idea. Suicide Life-Threat. 2001, 31, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorson, J.; Öberg, P.-A. Was there a suicide epidemic after Goethe’s Werther? Arch. Suicide Res. 2003, 7, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, É. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Voracek, M.; Herberth, A.; Till, B.; Strauss, M.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Eisenwort, B.; Sonneck, G. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide—Werther versus Papageno effects. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G. Media influence to suicide: The search for solutions. Arch. Suicide Res. 1998, 4, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. Media impacts on suicide: A quantitative review of 293 findings. Soc. Sci. Q. 2000, 81, 957–971. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, M.S. Suicide and media. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 932, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Blood, W. Suicide and the media. Part I: Reportage in nonfictional media. Crisis 2001, 22, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Blood, W. Suicide and the media. Part II: Portrayal in fictional media. Crisis 2001, 22, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.; Jamieson, P.; Romer, D. Media contagion and suicide among the young. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003, 46, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. Suicide in the media: A quantitative review of studies based on non-fictional stories. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005, 35, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisask, M.; Värnik, A. Media roles in suicide prevention: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Fu, K.-W.; Yip, P.S.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Stack, S.; Cheng, Q.; Pirkis, J. Changes in suicide rates following media reports on celebrity suicide: A meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2012, 66, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Braun, M.; Pirkis, J.; Till, B.; Stack, S.; Sinyor, M.; Tran, U.S.; Voracek, M.; Cheng, Q.; Arendt, F.; et al. Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 2020, 368, m575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.; Thompson, E.; Thomas, S.; Nesi, J.; Bettis, A.; Ransford, B.; Scopelliti, K.; Frazier, E.A.; Liu, R.T. Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 59, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.A.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Muehlenkamp, J.; Eckenrode, J.; Purington, A.; Barrera, P.; Baral-Abrams, G.; Kress, V.; Grace Martin, K.; Smith, E. Non-suicidal selfinjury as a gateway to suicide in adolescents and young adults. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.R.; Lanzillo, E.C.; Esposito, E.C.; Santee, A.C.; Nock, M.K.; Auerbach, R.P. Examining the course of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in outpatient and inpatient adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2017, 45, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Purington, A.; Gershkovich, M. Media, the Internet, and nonsuicidal self-injury. In M. Understanding Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Origins, Assessment, and Treatment; Nock, K., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Westers, N.; Lewis, S.; Whitlock, J.; Schatten, H.; Ammerman, B.; Andover, M.; Lloyd-Richardson, E. Media guidelines for the responsible reporting and depicting of non-suicidal self-injury. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blood, R.W.; Pirkis, J. Suicide and the media. Part III: Theoretical issues. Crisis 2001, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Stack, S. Media and Suicide. International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke, A.; Häfner, H. The Werther effect after television films: New evidence for an old hypothesis. Psychol. Med. 1988, 18, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Till, B.; Kapusta, N.D.; Voracek, M.; Dervic, K.; Sonneck, G. Copycat effects after media reports on suicide: A population-based ecologic study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, I.M. Imitation and suicide: A reexamination of the Werther Effect. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The effect of the media on suicide: The Great Depression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992, 22, 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.S.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Motto, J.A. Suicide and suggestibility: The role of the press. Am. J. Psychiatry 1967, 124, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motto, J.A. Newspaper influence on suicide. A controlled study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1970, 23, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, S.; Bergner, L. Suicide and newspapers: A replicated study. Am. J. Psychiatry 1973, 130, 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.P. Motor vehicle fatalities increase just after publicized suicide stories. Science 1977, 196, 1464–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P. Airplane accident fatalities increase just after stories about murder and suicide. Science 1978, 201, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P. Suicide, motor vehicle fatalities, and the mass media: Evidence toward a theory of suggestion. Am. J. Sociol. 1979, 84, 1150–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A.; Phillips, D.P. Suicidal motor vehicle fatalities in Detroit: A replication. Am. J. Sociol. 1981, 87, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, D.P. The impact of fictional television stories on U.S. adult fatalities: New evidence on the effect of the mass media on violence. Am. J. Sociol. 1982, 87, 1340–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A.; Phillips, D.P. Imitative suicides: A national study of the effects of television news stories. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 47, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The effect of the Jonestown suicides on American suicide rates. J. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 119, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, H.; Stack, S. The effect of television on national suicide rates. J. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 123, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Stipp, H. The impact of fictional television suicide stories on U.S. fatalities: A replication. Am. J. Sociol. 1984, 90, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P. The Werther effect. Suicide and other forms of violence are contagious. Science 1985, 25, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, R.B.; Behrends, R.W.; Lee, K.; Oliphant, J. Adolescent suicides modelled after television movie. Am. J. Psychiatry 1985, 142, 989. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, J.N.; Reiss, P.C. Same time next year: Aggregate analyses of the mass media and violent behavior. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1985, 50, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P.; Carstensen, L.L. Clustering of teenage suicides after television news stories about suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.S.; Shaffer, D. The impact of suicide in television movies. Evidence of imitation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, R.B.; Boyd, J.H. Television and suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 316, 876–877. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, S. Celebrities and suicide: A taxonomy and analysis, 1948–1983. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, D.P.; Paight, D.J. The impact of televised movies about suicide: A replicative study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 809–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P.; Carstensen, L.L. The effect of suicide stories on various demographic groups, 1968–1985. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1988, 18, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.S.; Shaffer, D.; Kleinman, M. The impact of suicide in television movies: Replication and commentary. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1988, 18, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, A.L. Fictional depiction of suicide in television films and imitation effects. Am. J. Psychiatry 1988, 145, 982–986. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Downey, G.; Milavsky, J.R.; Stipp, H. Clustering of suicides after television news stories about suicides: A reconsideration. Am. J. Psychiatry 1988, 145, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Downey, G.; Stipp, H.; Milavsky, J.R. Network television news stories about suicide and short term changes in total U.S. suicides. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1989, 177, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. A reanalysis of the impact of non celebrity suicides. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Psych. Epid. 1990, 25, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, S. Audience receptiveness, the media, and aged suicide, 1968–1980. J. Aging Stud. 1990, 4, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The impact of fictional television films on teenage suicide, 1984–1985. Soc. Sci. Q. 1990, 71, 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, S. Divorce, suicide, and the mass media: An analysis of differential identification, 1948–1980. J. Marriage Fam. 1990, 52, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, J.; Stack, S. The impact of hyper media coverage on suicide: New York City, 1910–1920. Soc. Sci. Q. 1990, 71, 619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz, A.; Brown, R.M.; Biblarz, D.N.; Pilgrim, M.; Bald, B. Media influence on attitudes toward suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1991, 21, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, I.M. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992, 22, 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, S. The media and suicide: A nonadditive model, 1968–1980. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1993, 23, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jobes, D.A.; Berman, A.L.; O’Carroll, P.W.; Eastgard, S.; Knickmeyer, S. The Kurt Cobain suicide crisis: Perspectives from research, public health, and the news media. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996, 26, 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hittner, J.B. How robust is the Werther effect? A re-examination of the suggestion-imitation model of suicide. Mortality 2005, 10, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, P.E.; Jamieson, K.H. Are news reports of suicide contagious? A stringent test in six US cities. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S.; Bowman, B. Durkheim at the movies: A century of suicide in film. Crisis 2011, 32, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.S.; Kleinman, M.H.; Lake, A.M.; Forman, J.; Midle, J.B. Newspaper coverage of suicide and initiation of suicide clusters in teenagers in the USA, 1988–1996: A retrospective, population-based, case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman, S.K. Suicide epidemics and newspaper reporting. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1985, 15, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousignant, M.; Mishara, B.L.; Caillaud, A.; Fortin, V.; Saint-Laurent, D. The impact of media coverage of the suicide of a well-known Quebec reporter: The case of Gaetan Girouard. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.S.; Santaella-Tenorio, J.; Keyes, K.M. Increase in suicides the months after the death of Robin Williams in the US. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinyor, M.; Schaffer, A.; Nishikawa, Y.; Redelmeier, D.A.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Sareen, J.; Levitt, A.J.; Kiss, A.; Pirkis, J. The association between suicide deaths and putatively harmful and protective factors in media reports. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2018, 190, E900–E907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.T.; Hawton, K.; Lee, C.T.; Chen, T.H. The influence of media reporting of the suicide of a celebrity on suicide rates: A population-based study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F.; Yip, P.S. The impact of media reporting of suicide on actual suicides in Taiwan, 2002–2005. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2011, 65, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Liao, S.F.; Teng, P.R.; Tsai, C.W.; Fan, H.F.; Lee, W.C.; Cheng, A.T. The impact of media reporting of the suicide of a singer on suicide rates in Taiwan. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F.; Gunnell, D.; Yip, P. The Impact of Media Reporting on the Emergence of Charcoal Burning Suicide in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.C.; Tsai, S.J.; Yang, C.H.; Shia, B.C.; Fuh, J.L.; Wang, S.J.; Peng, C.K.; Huang, N.E. Suicide and media reporting: A longitudinal and spatial analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 3427–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.S.; Kwok, S.; Cheng, Q.; Yip, P.; Chen, Y. The association of trends in charcoal-burning suicide with Google search and newspaper reporting in Taiwan: A time series analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, E.C.; Nam, J.M.; Park, S.; Cho, J.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, J.W.; Cho, E. The Werther effect of two celebrity suicides: An entertainer and a politician. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.W.; Chan, C. A study of the impact of thirteen celebrity suicides on subsequent suicide rates in South Korea from 2005 to 2009. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, W.Y.; Hwang, J.S.; Stack, S.J. To what extent does the reporting behavior of the media regarding a celebrity suicide influence subsequent suicides in South Korea? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014, 44, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, N.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Noh, M.S.; Yip, P.S. The impact of indiscriminate media coverage of a celebrity suicide on a society with a high suicide rate: Epidemiological findings on copycat suicides from South Korea. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Chang, Y.; Kim, N. Quantitative exponential modelling of copycat suicides: Association with mass media effect in South Korea. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2015, 24, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Oh, H. Does media coverage of a celebrity suicide trigger copycat suicides? Evidence from Korean cases. J. Media Econ. 2016, 29, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Choi, N.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.; An, H.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, Y.J. The Impact of celebrity suicide on subsequent suicide rates in the general population of Korea from 1990 to 2010. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. Media coverage of adolescent and celebrity suicides and imitation suicides among adolescents. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2019, 63, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.S.; Leung, C.M. Carbon monoxide poisoning as a new method of suicide in Hong Kong. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, P.S.; Fu, K.W.; Yang, K.C.; Ip, B.Y.; Chan, C.L.; Chen, E.Y.; Lee, D.T.; Law, F.Y.; Hawton, K. The effects of a celebrity suicide on suicide rates in Hong Kong. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 93, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, P.S.; Lee, D.T. Charcoal-burning suicides and strategies for prevention. Crisis 2007, 28, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Chen, F.; Yip, P.S. Media effects on suicide methods: A case study on Hong Kong 1998–2005. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K. Measuring mutual causation: Effects of suicide news on suicides in Japan. Soc. Sci. Res. 1991, 20, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The effect of the media on suicide: Evidence from Japan, 1955–1985. Suicide Life-Threat. 1996, 26, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, M.; Mori, K.; Matsubayashi, T. The effects of media reports of suicides by well-known figures between 1989 and 2010 in Japan. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, G.; Zalsman, G.; Polakevitch, J.; Shtein, N.; Sommerfeld, E.; Berger, E.; Apter, A. Effect of the broadcast of a television documentary about a teenager’s suicide in Israel on suicidal behavior and methods. Crisis 2005, 26, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakst, S.S.; Berchenko, Y.; Braun, T.; Shohat, T. The effects of publicized suicide deaths on subsequent suicide counts in Israel. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019, 23, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; Kar, S.K.; Marthoenis, M.; Arafat, S.Y.; Sharma, G.; Kaliamoorthy, C.; Ransing, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Pattnaik, J.I.; Shirahatti, N.B.; et al. Is there any link between celebrity suicide and further suicidal behaviour in India? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 8, 20764020964531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.W.; Yip, P.S. Estimating the risk for suicide following the suicide deaths of three Asian entertainment celebrities: A meta-analysis approach. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, T.A. The, BBC “Befrienders” series and its effects. Br. J. Psychiatry 1974, 124, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holding, T.A. Suicide and “The Befrienders”. Br. Med. J. 1975, 3, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Barraclough, B.M.; Shepherd, D.; Jennings, C. Do newspaper reports of coroners’ inquests incite people to commit suicide? Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 131, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, J.R.; Donnan, S. Suicide by burning—A current epidemic. Br. Med. J. 1979, 2, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashton, J.R.; Donnan, S. Suicide by burning as an epidemic phenomenon: An analysis of 82 deaths and inquests in England and Wales in 1978–9. Psychol. Med. 1981, 11, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.J.; Walsh, S. Soap may seriously damage your health. Lancet 1986, 1, 6S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, B.P. Emotional crises imitating television. Lancet 1986, 1, 1036–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, S. The aftermath of Angie’s overdose. Is soap (opera) damaging to your health? Br. Med. J. 1987, 294, 954–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, S.; Hawton, K.; Whitehead, L.; Fagg, J.; Eagle, M. Media influence on parasuicide. A study of the effects of a television drama portrayal of paracetamol self-poisoning. Br. J. Psychiatry 1995, 167, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Simkin, S.; Deeks, J.J.; O’Connor, S.; Keen, A.; Altman, D.G.; Philo, G.; Bulstrode, C. Effects of a drug overdose in a television drama on presentations to hospital for self-poisoning: Time series and questionnaire study. Br. Med. J. 1999, 318, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzersdorfer, E.; Sonneck, G.; Nagel-Kuess, S. Newspaper reports and suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 327, 502–503. [Google Scholar]

- Sonneck, G.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Nagel Kuess, S. Imitative suicide on the Viennese subway. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzersdorfer, E.; Sonneck, G. Preventing suicide by influencing mass-media reporting. The Viennese experience 1980–1996. Arch. Suicide Res. 1998, 4, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzersdorfer, E.; Voracek, M.; Sonneck, G. A dose-response relationship between imitational suicides and newspaper distribution. Arch. Suicide Res. 2004, 8, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Sonneck, G. Assessing the impact of media guidelines for reporting on suicides in Austria: Interrupted time series analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2007, 41, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, K. Modelling and suicide: A test of the Werther effect. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 31, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunrath, S.; Baumert, J.; Ladwig, K.H. Increasing railway suicide acts after media coverage of a fatal railway accident? An ecological study of 747 suicidal acts. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2011, 65, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladwig, K.-H.; Kunrath, S.; Lukaschek, K.; Baumert, J. The railway suicide death of a famous German football player: Impact on the subsequent frequency of railway suicide acts in Germany. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Martin, P.; Prat, S.; Bouyssy, M.; O’Byrne, P. Plastic bag asphyxia—A case report. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2009, 16, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queinec, R.; Beitz, C.; Contrand, B.; Jougla, E.; Leffondré, K.; Lagarde, E.; Encrenaz, G. Copycat effect after celebrity suicides: Results from the French national death register. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R. Effects of newspaper stories on the incidence of suicide in Australia: A research note. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1995, 29, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, N.F. Newspaper stories and the incidence of suicide. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1995, 29, 699. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.; Koo, L. Celebrity suicide: Did the death of Kurt Cobain affect suicides in Australia? Arch. Suicide Res. 1997, 3, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.E.; Burgess, P.M.; Francis, C.; Blood, R.W.; Jolley, D.J. The relationship between media reporting of suicide and actual suicide in Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2874–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Currier, D.; Too, L.S.; Bryant, M.; Bartlett, S.; Sinyor, M.; Spittal, M.J. Suicides in Australia following media reports of the death of Robin Williams. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiat. 2020, 54, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, S. Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2003, 57, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, V.; Whitley, R. Media coverage of Robin Williams’ suicide in the United States: A contributor to contagion? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, S.; Schmidtke, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Upanne, M.; Osvath, P. Mass media, cultural attitudes, and suicide. Results of an international comparative study. Crisis 2001, 22, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Rossetto, A.; Nicholas, A.; Ftanou, M.; Robinson, J.; Reavley, N. Suicide prevention media campaigns: A systematic literature review. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.; Michel, K.; Valach, L. Suicide reporting in the Swiss print media: Responsible or irresponsible? Eur. J. Public Health 1997, 7, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, K.; Frey, C.; Schlaepfer, T.E.; Valach, L. Suicide reporting in the Swiss print media: Frequency, form and content of articles. Eur. J. Public Health 1995, 5, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Quiring, O. The press coverage of celebrity suicide and the development of suicide frequencies in Germany. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Burgess, P.; Blood, R.W.; Francis, C. The newsworthiness of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007, 37, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimann, G.; Fishman, G. Reconstructing suicide: Reporting suicide in the Israeli press. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1995, 72, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.W.; Chan, Y.Y.; Yip, P.S. Newspaper reporting of suicides in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Guangzhou: Compliance with WHO media guidelines and epidemiological comparisons. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2011, 65, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Blood, R.W.; Beautrais, A.; Burgess, P.; Skehan, J. Media guidelines on the reporting of suicide. Crisis 2006, 27, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.W.; Yip, P.S. Changes in reporting of suicide news after the promotion of the WHO media recommendations. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008, 38, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Dare, A.; Blood, R.W.; Rankin, B.; Williamson, M.; Burgess, P.; Jolley, D. Changes in media reporting of suicide in Australia between 2000/01 and 2006/07. Crisis 2009, 30, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, K.; Frey, C.; Wyss, K.; Valach, L. An exercise in improving suicide reporting in print media. Crisis 2000, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, P.; Jamieson, K.H.; Romer, D. The responsible reporting of suicide in print journalism. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003, 46, 1643–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatum, P.T.; Canetto, S.S.; Slater, M.D. Suicide coverage in U.S. newspapers following the publication of the media guidelines. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010, 40, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creed, M.; Whitley, R. Assessing fidelity to suicide reporting guidelines in Canadian news media: The death of Robin Williams. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. Media guidelines and suicide: A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 262, 112690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Country Studied | Media Studied | Type of Suicide | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] Phillips 1974 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [6] Niederkrotenthaler et. al. 2010 | Austria | Newspapers | Real suicides | Mixed results |

| [25] Schmidtke and Häfner 1988 | Germany | Six-episode TV movie | Fictional suicides (railway suicide) | Werther effect |

| [26] Niederkrotenthaler et al. 2009 | Austria | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [27] Wasserman 1984 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Mixed results (Werther effect for celebrity suicide) |

| [28] Stack 1992 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Mixed results |

| [31] Motto 1967 | USA | Newspaper (cessation) | Real suicides | No effect |

| [32] Motto 1970 | USA | Newspaper (cessation) | Real suicides | Werther effect (age/gender specific) |

| [33] Blumenthal and Bergner 1973 | USA | Newspaper (cessation) | Real suicides | Werther effect (age/gender specific) |

| [34] Phillips 1977 | USA | Newspapers | Motor vehicle fatalities | Werther effect |

| [35] Phillips 1978 | USA | Newspapers | Airplane accident | Werther effect |

| [36] Phillips 1979 | USA | Newspapers | Motor vehicle fatalities | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [37] Bollen 1981 | USA | Newspapers | Motor vehicle fatalities | Werther effect |

| [38] Phillips 1982 | USA | TV soap opera | Fictional suicides (Motor vehicle fatalities) | Werther effect |

| [39] Bollen and Phillips 1982 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [40] Stack 1983 | USA | Mixed media | Real suicides | No effect |

| [41] Horton and Stack1984 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | No effect |

| [42] Kessler and Stipp 1984 | USA | TV soap opera (replication of Phillips 1982 [38]) | Fictional suicides (Motor vehicle fatalities) | No effect |

| [43] Phillips 1985 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [44] Ostroff et al. 1985 | USA | Fictional telemovies | Fictional suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [45] Baron and Reiss 1985 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | No effect |

| [46] Phillips and Carstensen 1986 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [47] Gould and Shaffer 1986 | USA | TV movies | Fictional suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [48] Ostroff and Boyd 1987 | USA | Fictional telemovies | Fictional suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [49] Stack 1987 | USA | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (celebrity effect) |

| [50] Phillips and Paight 1987 | USA | TV movies | Fictional suicides | No effect |

| [51] Phillips and Carstensen 1988 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [52] Gould and Shaffer 1988 | USA | TV movies (Replication of Gould and Shaffer 1986 [47]) | Fictional suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [53] Berman 1988 | USA | TV movies | Fictional suicides | No effect |

| [54] Kessler et al. 1988 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | No effect |

| [55] Kessler et al. 1989 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | No effect |

| [56] Stack 1990 | USA | Newspapers | Real (non-celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [57] Stack 1990 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [58] Stack 1990 | USA | TV movies | Fictional suicides | No effect |

| [59] Stack 1990 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [60] Gundlach and Stack 1999 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [61] Biblarz et al 1991 | USA | Movie | Fictional suicide | Werther effect |

| [62] Wasserman 1992 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [63] Stack 1993 | USA | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [64] Jobes et al. 1996 | USA | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | No effect |

| [65] Hittner 2005 | USA | TV network news (Replication of Phillips and Carstensen 1986 [46] & 1988 [51]) | Real suicides | Mixed results |

| [66] Romer et al. 2006 | USA | Mixed media | Real suicides | Werther effect/Mixed results |

| [67] Stack and Bowman 2011 | USA | Movies | Fictional suicide | Werther effect |

| [68] Gould et al. 2014 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (age specific) |

| [69] Littman 1985 | Canada | Newspapers | Real suicides | No effect |

| [70] Tousignant et al. 2005 | Canada | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [71] Fink et al. 2018 | Canada | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [72] Sinyor et al. 2018 | Canada | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [73] Cheng et al. 2007 | Taiwan | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (gender/method specific: hanging) |

| [74] Chen et al. 2011 | Taiwan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [75] Chen et al. 2012 | Taiwan | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (age/gender/method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [76] Chen et al. 2013 | Taiwan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [77] Yang et al. 2013 | Taiwan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [78] Chang et al. 2015 | Taiwan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (gender/method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [79] Kim et al. 2013 | South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (method specific: hanging and jumping) |

| [80] Fu et al. 2013 | South Korea | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [81] Lee et al. 2014 | South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [82] Ju et al. 2014 | South Korea | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (age/gender specific) |

| [83] Suh et al. 2015 | South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [84] Choi et al. 2016 | South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [85] Park et al. 2016 | South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [86] Lee 2019 | South Korea | TV network news | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [87] Chung and Leung 2001 | Hong Kong | Newspapers | Real suicide | Werther effect (age/method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [88] Yip et al. 2006 | Hong Kong | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (age/method specific: jumping) |

| [89] Yip and Lee 2007 | Hong Kong | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [90] Cheng et al. 2017 | Hong Kong | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (method specific: charcoal burning) |

| [91] Ishii 1991 | Japan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [92] Stack 1996 | Japan | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect (nationality specific) |

| [93] Ueda et al. 2014 | Japan | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [94] Shoval et al. 2005 | Israel | TV documentary | Real suicide | Mixed results |

| [95] Bakst et al. 2019 | Israel | Newspapers | Real suicides | No effect |

| [96] Menon et al. 2020 | India | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [97] Fu and Yip 2009 | Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [98] Holding 1974 | United Kingdom | TV series | Fictional suicide | Mixed results |

| [99] Holding 1975 | United Kingdom | TV series | Fictional suicide | Mixed results |

| [100] Barraclough et al. 1977 | United Kingdom | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [101] Ashton and Donnan 1979 | United Kingdom | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [102] Ashton and Donnan 1981 | United Kingdom | Newspaper | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [103] Ellis and Walsh | United Kingdom | TV soap operas | Fictional suicide | Werther effect |

| [104] Fowler 1986 | United Kingdom | TV soap operas | Fictional suicide | Werther effect |

| [105] Platt 1987 | United Kingdom | TV soap operas | Fictional suicide | No effect |

| [106] Simkin et al. 1995 | United Kingdom | TV dramas | Fictional suicide | No effect |

| [107] Hawton et al. 1999 | United Kingdom | TV series | Fictional suicide | Werther effect |

| [108] Etzersdorfer et al. 1992 | Austria | Newspapers | Real suicides | Papageno effect |

| [109] Sonneck et al. 1994 | Austria | Newspapers | Real suicides | Papageno effect |

| [110] Etzersdorfer and Sonneck 1998 | Austria | Newspapers | Real suicides | Papageno effect |

| [111] Etzersdorfer et al. 2004 | USA | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [112] Niederkrotenthaler and Sonneck 2007 | Austria | Newspapers | eal suicides | Papageno effect |

| [113] Jonas 1992 | Germany | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [114] Kunrath et al. 2011 | Germany | Mixed media | Real suicides | Werther effect (method specific: railway suicide) |

| [115] Ladwig et al. 2012 | Germany | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (method specific: railway suicide) |

| [116] Saint-Martin et al. 2009 | France | Movie | Fictional suicide | Werther effect (method specific: plastic bag asphyxia) |

| [117] Queinec et al. 2011 | France | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Mixed results |

| [118] Hassan 1995 | Australia | Newspapers | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [119] Hills 1995 | Australia | Newspapers | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect |

| [120] Martin and Koo 1997 | Australia | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | No effect |

| [121] Pirkis et al. 2006 | Australia | Mixed media | Real suicides | Werther effect |

| [122] Pirkis et al. 2020 | Australia | Mixed media | Real (celebrity) suicides | Werther effect (method specific: hanging) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domaradzki, J. The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052396

Domaradzki J. The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052396

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomaradzki, Jan. 2021. "The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052396

APA StyleDomaradzki, J. (2021). The Werther Effect, the Papageno Effect or No Effect? A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052396