Why and How Does Empowering Leadership Promote Proactive Work Behavior? An Examination with a Serial Mediation Model among Hotel Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

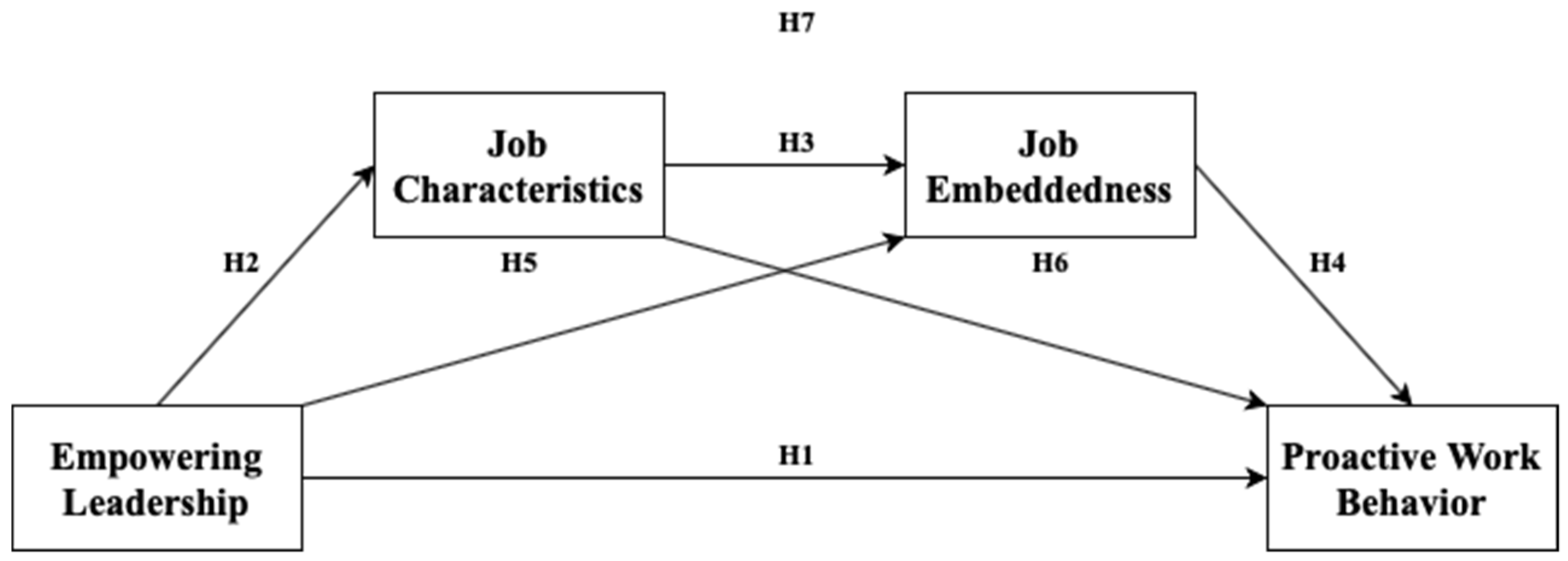

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Proactive Work Behavior

2.2. Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Job Characteristics

2.3. Relationship among Job Characteristics, Job Embeddedness, and Proactive Work Behavior

2.4. Serial Mediation Roles of Job Characteristics and Job Embeddedness

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Pilot Test

3.3. Sample Frame and Data Collection

3.4. Construct Measurement

3.5. Analytic Approach

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Statistics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

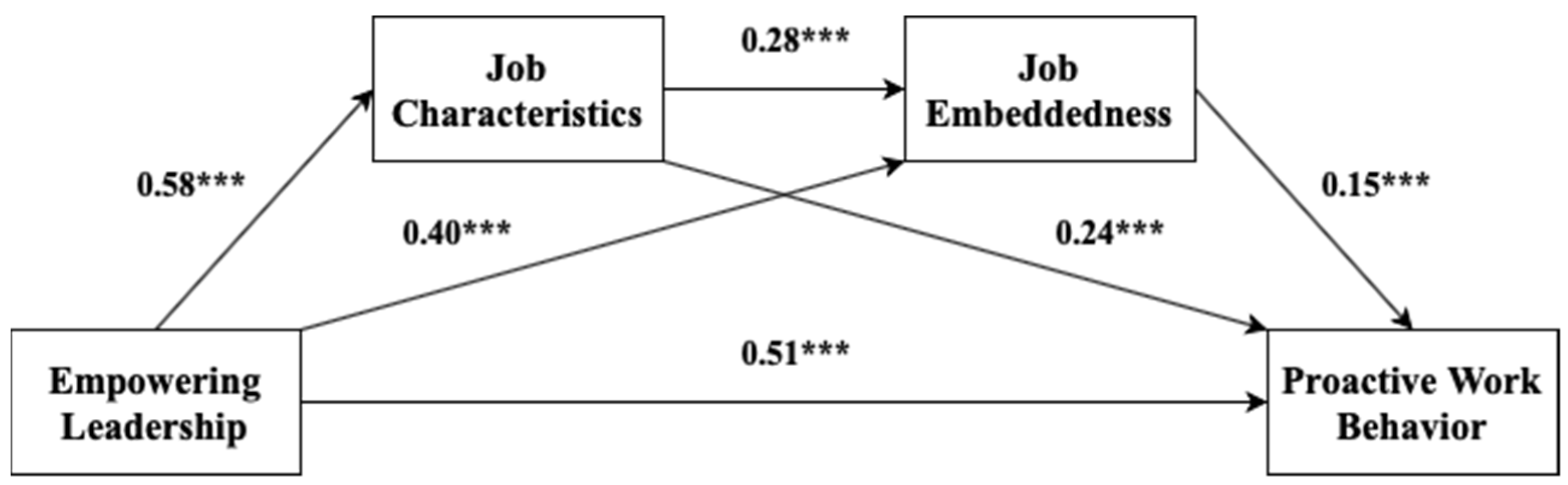

4.3. Path Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Suggestions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millear, P.; Liossis, P.; Shochet, I.M.; Biggs, H.; Donald, M. Being on PAR: Outcomes of a Pilot Trial to Improve Mental Health and Wellbeing in the Workplace with the Promoting Adult Resilience (PAR) Program. Behav. Chang. 2008, 25, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Ji, Y.-H.; Baek, W.-Y.; Byon, K.K. Structural Relationship among Physical Self-Efficacy, Psychological Well-Being, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior among Hotel Employees: Moderating Effects of Leisure-Time Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. How Does High-Performance Work System Prompt Job Crafting through Autonomous Motivation: The Moderating Role of Initiative Climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, A.; Takao, S.; Mineyama, S.; Nishiuchi, K.; Komatsu, H.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a supervisory education for positive mental health in the workplace: A quasi-experimental study. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, K.; Martin, A.; Bartlett, L.; Dawkins, S.; Sanderson, K. Workplace mental health: An international review of guidelines. Prev. Med. 2017, 101, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabala, C.; Charzynska, K.; Mroziak, B. Psychosocial interventions in workplace mental health promotion: An overview. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, I70–I84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, S.; Jain, A.; Iavicoli, S.; Di Tecco, C. An Evaluation of the Policy Context on Psychosocial Risks and Mental Health in the Workplace in the European Union: Achievements, Challenges, and the Future. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 213089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, P. Mental health and the workplace: Issues for developing countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2009, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Torres, E.; Ingram, W.; Hutchinson, J. A review of high performance work practices (HPWPs) literature and recommendations for future research in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-Performance Work System, Work Well-Being, and Employee Creativity: Cross-Level Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Lu, L.; Cao, Y.; Du, Q. The High-Performance Work System, Employee Voice, and Innovative Behavior: The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.; Gerhart, B. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Organizational Performance: Progress and Prospects. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, P.C.; Liu, W.; MacCurtain, S.; Guthrie, J. High Performance Work Systems in Ireland—The Economic Case. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/High-Performance-Work-Systems-in-Ireland-The-Case-Flood-Liu/f54f7346607fc8586d9e261fd921a7dc195e2b95 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Karatepe, O.M. High-performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: The mediation of work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The Impact Of Human Resource Management Practices On Turnover, Productivity, And Corporate Financial Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; Tseng, K.-J. Effects of selected positive resources on hospitality service quality: The mediating role of work engagement. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. Linking sustainable human resource management in hospitality: An empirical investigation of the integrated mediated moderation model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karman, A. Understanding sustainable human resource management—Organizational value linkages: The strength of the SHRM system. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Harry, W.; Zink, K.J. Sustainability and Human Resource Management: Developing Sustainable Business Organizations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Vanhala, S. Sustainable human resource management with salience of stakeholders: A top management perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, A. To Empower or Not to Empower Your Sales Force? An Empirical Examination of the Influence of Leadership Empowerment Behavior on Customer Satisfaction and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.; Menguc, B.; Jung, Y.S. Unpacking the relationship between empowering leadership and service-oriented citizenship behaviors: A multilevel approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 558–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.; Robert, C. Empowerment, organizational commitment, and voice behavior in the hospitality industry: Evidence from a multinational sample. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Gallego-Burín, A.R.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. Effects of different leadership styles on hospitality workers. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Ling, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wu, X. Why does empowering leadership occur and matter? A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Iun, J.; Liu, A.; Gong, Y. Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? The differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Willis, S.; Tian, A.W. Empowering leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Ruiz-Moreno, A. Achieving engagement among hospitality employees: A serial mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Shah Syed, I. Frontline employees’ high-performance work practices, trust in supervisor, job-embeddedness and turnover intentions in hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi Homayoun, P.; Karatepe Osman, M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee outcomes: The mediating role of career adaptability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1112–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Parker, S.K. The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior: A perspective from attachment theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1025–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindl, U.K.; Parker, S.K. Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol 2: Selecting and Developing Members for the Organization; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 567–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Schmitt, A. Work design and proactivity. In Proactivity at Work: Making Things Happen in Organizations, 1st ed.; Parker, S.K., Bindl, U.K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, M.A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Khalid, S. Empowering leadership and proactive behavior: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of leader-follower distance. Abasyn Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkorezis, P. Principal empowering leadership and teacher innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Self, T.T. Psychological Diversity Climate, Organizational Embeddedness, and Turnover Intentions: A Conservation of Resources Perspective. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why People Stay: Using Job Embeddedness to Predict Voluntary Turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, D.; McKay, P.F.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. When and how is job embeddedness predictive of turnover? A meta-analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglio, R.P.; Gelgec, S. Exploring the structure and meaning of public service motivation in the Turkish public sector: A test of the mediating effects of job characteristics. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. Does job embeddedness mediate the effects of coworker and family support on creative performance? An empirical study in the hotel industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 15, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.Q. Job characteristics, job embeddedness, and turnover intention: The case of Vietnam. J. Int. Interdiscip. Bus. Res. 2015, 2, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive" model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.A.; Arad, S.; Rhoades, J.A.; Drasgow, F. The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, S.; Martinsen, Ø.L. Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.B.; Chapman, A.R. The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, B.; McIlveen, P.; Perera, H.N. Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between career adaptability and career optimism. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.; Robert, C. Differential effects of empowering leadership on in-role and extra-role employee behaviors: Exploring the role of psychological empowerment and power values. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1743–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Lawler, E.E. Employee reactions to job characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Work Redesign. 1980. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/105960118200700110 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Noe, R.A.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Gerhart, B.; Wright, P.M. Fundamentals of Human Resource Management; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Ghiselli, R. Why do you feel stressed in a “smile factory”? Hospitality job characteristics influence work–family conflict and job stress. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ghiselli, R.; Law, R.; Ma, J. Motivating frontline employees: Role of job characteristics in work and life satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 27, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Hancer, M.; Im, J.Y. Job Characteristics, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment for Hotel Workers in Turkey. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.-W.; Yang, H.-O.; Chu, K.-L. Correlations among Satisfaction with Educational Training, Job Performance, Job Characteristics, and Person-Job Fit. Anthropologist 2014, 17, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, A. Effects of individual and job characteristics on hotel contact employees’ work engagement and their performance outcomes: A case study from Poland. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Bakker, A.B. Work engagement: Introduction. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Harris, T.B. 3D Team Leadership: A New Approach for Complex Teams; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.B.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Empowering Leadership, Risk-Taking Behavior, and Employees’ Commitment to Organizational Change: The Mediated Moderating Role of Task Complexity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Burton, J.P.; Sablynski, C.S. Job embeddedness: Current research and future directions. In Innovative Theory and Empirical Research on Employee Turnover; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2004; pp. 153–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgievski, M.; Hobfoll, S. Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. Handb. Stress Burn. Health Care 2008, 1, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Wheeler, A.R. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress 2008, 22, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiazad, K.; Holtom, B.C.; Hom, P.W.; Newman, A. Job embeddedness: A multifoci theoretical extension. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiazad, K.; Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L. Psychological contract breach and employee innovation: A conservation of resources perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felps, W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Hekman, D.R.; Lee, T.W.; Holtom, B.C.; Harman, W.S. Turnover Contagion: How Coworkers’ Job Embeddedness and Job Search Behaviors Influence Quitting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ayoun, B. Is negative workplace humor really all that “negative”? Workplace humor and hospitality employees’ job embeddedness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Kralj, A.; Solnet, D.J.; Goh, E.; Callan, V. Thinking job embeddedness not turnover: Towards a better understanding of frontline hotel worker retention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Ellingson, J.E. The impact of coworker support on employee turnover in the hospitality industry. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, C.T.; Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Work design as an approach to person-environment fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffeth, R.W. Moderation of the effects of job enrichment by participation: A longitudinal field experiment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 35, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.I.; Martinez, L.F.; Lamelas, J.P.; Rodrigues, R.I. Mediation of job embeddedness and satisfaction in the relationship between task characteristics and turnover: A multilevel study in Portuguese hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Ngeche, R.N. Does Job Embeddedness Mediate the Effect of Work Engagement on Job Outcomes? A Study of Hotel Employees in Cameroon. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yan, J.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Lin, W.; Bhattacharjee, A. What makes employees more proactive? Roles of job embeddedness, the perceived strength of the HRM system and empowering leadership. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2020, 58, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hua, N. Transformational leadership, proactive personality and service performance: The mediating role of organizational embeddedness. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Arici, H.E.; Ilgen, H. Blackbox between job crafting and job embeddedness of immigrant hotel employees: A serial mediation model. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 3935–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.N.; Richard, D.C.S.; Kubany, E.S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- TaiwanTourismBureau. Report on Tourist Hotel Operations in Taiwan; Taiwan Tourism Bureau: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, C.D.; Bennett, R.J.; Jex, S.M.; Burnfield, J.L. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM SPSS Amos 24 User’s Guide; Amos Development Corporation: Meadville, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.-Y. Tests of the Three-Path Mediated Effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Uppersaddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J. Excel StatTools. Stats Tools Package. 2016. Available online: http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Main_Page (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J. When Is Proactivity Wise? A Review of Factors That Influence the Individual Outcomes of Proactive Behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics (n = 461) | Frequency (s) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 278 | 60.3 |

| Male | 183 | 39.7 |

| Age | ||

| 20 or below | 19 | 4.1 |

| 21–30 | 337 | 73.1 |

| 31–40 | 48 | 10.4 |

| 41–50 | 29 | 6.3 |

| 51–60 | 24 | 5.2 |

| 61 or above | 4 | 0.9 |

| Work experience | ||

| Below 1 year | 71 | 15.4 |

| 1 year or more, less than 3 years | 218 | 47.3 |

| 3 year or more, less than 5 years | 62 | 13.4 |

| 5 year or more, less than 7 years | 27 | 5.9 |

| 7 year or more, less than 9 years | 20 | 4.3 |

| 9 years of above | 63 | 13.7 |

| Education level | ||

| Junior high school or below | 7 | 1.5 |

| Senior high school | 49 | 10.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 379 | 82.2 |

| Postgraduate degree or above | 26 | 5.6 |

| Position | ||

| Managerial | 78 | 16.9 |

| Non-managerial | 383 | 83.1 |

| Job type | ||

| Full-time | 421 | 91.3 |

| Part-time | 40 | 8.7 |

| Constructs | χ2 | χ2/df | GFI | AGFI | SRMR | CFI | NNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empowering Leadership | 78.59 | 1.57 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.04 |

| Job Characteristics | 345.54 | 1.52 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Job Embeddedness | 29.57 | 2.11 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Proactive Work Behavior | 120.86 | 1.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Overall Model | 257.88 | 1.57 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| Mean | S.D. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Empowering Leadership | 5.10 | 0.88 | (0.81) | |||

| 2. Job Characteristics | 4.84 | 0.60 | 0.56 ** | (0.67) | ||

| 3. Job Embeddedness | 4.46 | 0.80 | 0.56 ** | 0.52 ** | (0.64) | |

| 4. Proactive Work Behavior | 5.30 | 0.80 | 0.73 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.56 ** | (0.79) |

| Chi-Square | df | p-Value | Invariant? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | ||||

| Unconstrained | 709.83 | 144 | ||

| Fully Constrained | 946.80 | 150 | ||

| Number of Groups | 2 | |||

| Difference | 236.97 | 6 | 0.000 | NO |

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimate | p-Value | Percentile 99% CI [Lower, Upper] | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EL → PWB | 0.51 | p < 0.001 | [0.40, 0.61] | Supported |

| H2 | EL → JC | 0.58 | p < 0.001 | [0.49, 0.65] | Supported |

| H3 | JC → JE | 0.28 | p < 0.001 | [0.22, 0.55] | Supported |

| H4 | JE → PWB | 0.15 | p < 0.001 | [0.04, 0.26] | Supported |

| H5 | EL → JC → PWB | 0.14 | p < 0.001 | [0.09, 0.20] | Supported |

| H6 | EL → JE → PWB | 0.06 | p < 0.001 | [0.02, 0.11] | Supported |

| H7 | EL → JC → JE → PWB | 0.02 | p < 0.001 | [0.01, 0.05] | Supported |

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.23 | p < 0.001 | [0.15, 0.30] | ||

| Total Effect | 0.73 | p < 0.001 | [0.66, 0.79] | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.-J.; Yang, I.-H. Why and How Does Empowering Leadership Promote Proactive Work Behavior? An Examination with a Serial Mediation Model among Hotel Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052386

Wang C-J, Yang I-H. Why and How Does Empowering Leadership Promote Proactive Work Behavior? An Examination with a Serial Mediation Model among Hotel Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052386

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chung-Jen, and I-Hsiu Yang. 2021. "Why and How Does Empowering Leadership Promote Proactive Work Behavior? An Examination with a Serial Mediation Model among Hotel Employees" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052386

APA StyleWang, C.-J., & Yang, I.-H. (2021). Why and How Does Empowering Leadership Promote Proactive Work Behavior? An Examination with a Serial Mediation Model among Hotel Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052386