Development of a Structured Interview to Explore Interpersonal Schema of Older Adults Living Alone Based on Autobiographical Memory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the Structured Interview

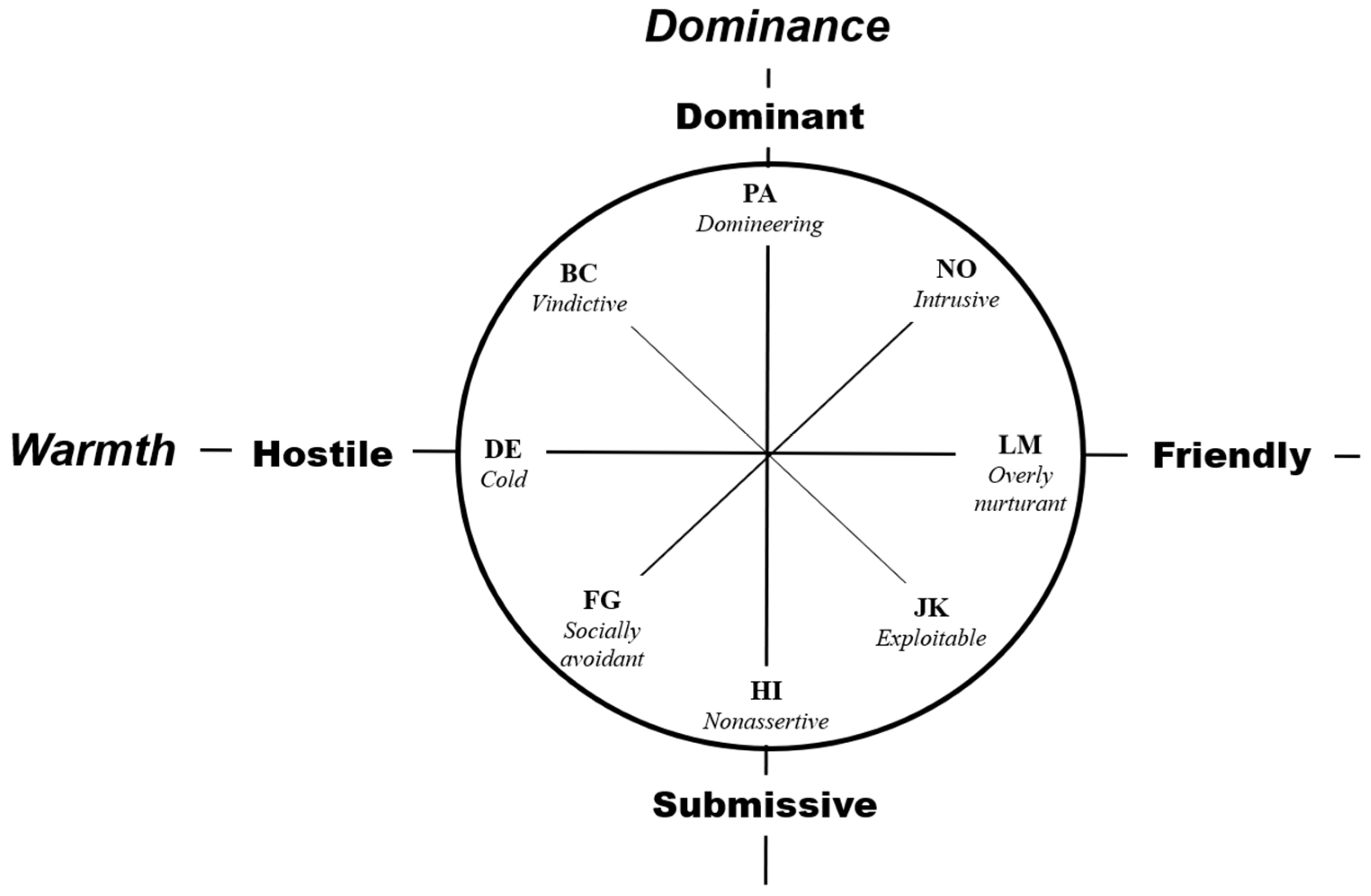

Literature Review and Initial Development

2.2. The Pilot Study

2.3. Final Interview Protocol

2.4. Participants

2.5. Additional Outcome Measures

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Inter-Rater Agreement of IAM

3.2. Item-Total Correlation

3.3. Criterion Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables (%) | Indexes | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA (15.2) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 84.0 |

| Wm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 84.0 | |

| CF | 0.0 | 100.0 | 84.0 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 0.0 | 100.0 | 84.0 | |

| BC (51.5) | Dm | 64.6 | 43.5 | 54.3 |

| Wm | 64.6 | 32.6 | 48.9 | |

| CF | 70.8 | 28.3 | 50.0 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 54.2 | 54.3 | 54.3 | |

| DE (47.4) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 53.5 |

| Wm | 48.8 | 75.5 | 63.0 | |

| CF | 39.5 | 73.5 | 57.6 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 48.8 | 73.5 | 62.0 | |

| FG (30.2) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 69.2 |

| Wm | 7.1 | 93.7 | 67.0 | |

| CF | 10.7 | 100.0 | 72.5 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 17.9 | 95.2 | 71.4 | |

| HI (40.6) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 59.3 |

| Wm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 59.3 | |

| CF | 27.0 | 94.4 | 67.0 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 35.1 | 85.2 | 64.8 | |

| JK (30.9) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 69.6 |

| Wm | 3.6 | 100.0 | 70.7 | |

| CF | 0.0 | 100.0 | 69.9 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 3.6 | 100.0 | 70.7 | |

| LM (40.4) | Dm | 0.0 | 98.2 | 59.6 |

| Wm | 37.8 | 86.0 | 67.0 | |

| CF | 27.0 | 89.5 | 64.9 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 32.4 | 86.0 | 64.9 | |

| NO (10.1) | Dm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 89.4 |

| Wm | 0.0 | 100.0 | 89.4 | |

| CF | 0.0 | 100.0 | 89.4 | |

| Dm + Wm + CF | 20.0 | 100.0 | 91.5 |

References

- Kim, Y.S. Mental Health Care with Family Physicians. Korean J. Fam. Pract. 2013, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K. Current status of living alone in old age and policy response strategies. Health Welf. Issue Focus 2015, 300, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.; Lee, M. Identifying the effect of living alone on life in later adulthood: Comparison between living alone and those living with others with a propensity score matching analysis. Health Soc Welf Rev 2018, 38, 196–226. [Google Scholar]

- Aday, R.H.; Kehoe, G.C.; Farney, L.A. Impact of senior center friendships on aging women who live alone. J. Women Aging 2006, 18, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H. A plan to revitalize social relations for the older adults living alone “A project to make friends for the older adults living alone”. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2017, 2017, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.; Colson, T. Senior community center as a social engagement platform for older adults in nepal: An adaptation of western concept. Innov. Aging 2019, 3 (Suppl. 1), S979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.W. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, F.Z.; Van Praag, L.; Nicaise, I. A qualitative study of how exclusion processes shape friendship development among Turkish-Belgian university students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Vazire, S. On friendship development and the Big Five personality traits. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtman, M.B. Interpersonal circumplex. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 2364–2373. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, L.M. Interpersonal Foundations of Psychopathology; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, J.S.; Pincus, A.L. Conceptions of personality disorders and dimensions of personality. Psychol. Assess. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 1, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, J.F.; Kurtz, J.E.; Markey, P.M. Evaluating Circumplex Structure in the Interpersonal Scales for the NEO-PI-3. Assessment 2018, 25, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, P.D.; Wiggins, J.S. Extension of the interpersonal adjective scales to include the big five dimensions of personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.V.; Yardley, A.E.; Thomas, K.M. Mapping big five personality traits within and across domains of interpersonal functioning. Assessment 2020, 1073191120913952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeYoung, C.G.; Weisberg, Y.J.; Quilty, L.C.; Peterson, J.B. Unifying the aspects of the Big Five, the interpersonal circumplex, and trait affiliation. J. Personal. 2013, 81, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, T.; Tarsia, M.; Schwannauer, M. Interpersonal styles in major and chronic depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiger, T.A. Personality, interpersonal circumplex, and DSM–5: A commentary on five studies. J. Personal. Assess. 2010, 92, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.; Anderson, T. Interpersonal subtypes within social anxiety: The identification of distinct social features. J. Personal. Assess. 2019, 101, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauthmann, J.F.; Kolar, G.P. Positioning the Dark Triad in the interpersonal circumplex: The friendly-dominant narcissist, hostile-submissive Machiavellian, and hostile-dominant psychopath? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.R.; Safran, J.D. Assessing interpersonal schemas: Anticipated responses of significant others. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 13, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.D. Measuring personality constructs: The advantages and disadvantages of self-reports, informant reports and behavioural assessments. Enquire 2008, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.W.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Sudano, J.; Patterson, M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2000, 55, S368–S374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.S.; Chey, J.Y. Literacy and neuropsychological functions in the older Korean adults. J. Korean Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 8, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Blagov, P.S.; Singer, J.A. Four dimensions of self-defining memories (specificity, meaning, content, and affect) and their relationships to self-restraint, distress, and repressive defensiveness. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 481–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.A.; Blagov, P.; Berry, M.; Oost, K.M. Self-defining memories, scripts, and the life story: Narrative identity in personality and psychotherapy. J. Personal. 2013, 81, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouizegarene, N.; Philippe, F.L. Longitudinal directive effect of need satisfaction in self-defining memories on friend related identity processing styles and friend satisfaction. Self Identity 2018, 17, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F.L.; Koestner, R.; Lekes, N. On the directive function of episodic memories in people’s lives: A look at romantic relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, M.; Wilson, B.; Baddeley, A. The autobiographical memory interview: A new assessment of autobiographical and personal semantic memory in amnesic patients. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1989, 11, 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Broadbent, K. Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1986, 95, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, K.; Hallford, D.J.; Vanderveren, E.; Austin, D.W.; Raes, F. The computerized scoring algorithm for the autobiographical memory test: Updates and extensions for analyzing memories of English-speaking adults. Memory 2019, 27, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, M.A. Memory and the self. J. Mem. Lang. 2005, 53, 594–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, D.; Rubin, D.C. Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Mem. Cogn. 2004, 32, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glück, J.; Bluck, S. Looking back across the life span: A life story account of the reminiscence bump. Mem. Cogn. 2007, 35, 1928–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherman, A.Z.; Salgado, S.; Shao, Z.; Berntsen, D. Life script events and autobiographical memories of important life story events in Mexico, Greenland, China, and Denmark. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2017, 6, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R.T. Presentation modality and mode of recall in verbal false memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2001, 27, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.W.; Allik, J.P. A developmental study of visual and auditory short-term memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1973, 12, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.L.; Ryu, S.H.; Moon, S.W.; Choo, I.H.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, J.C.; Do, Y.J. Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its’ short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2010, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.L.; Ryu, S.H.; Moon, S.W.; Choo, I.H.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, J.C. A normative study of the Mini-Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) and its short form (SMMSE-DS) in the Korean elderly. J. Korean Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 14, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Polsinelli, A.J.; Rentscher, K.E.; Glisky, E.L.; Moseley, S.A.; Mehl, M.R. Interpersonal focus in the emotional autobiographical memories of older and younger adults. GeroPsych 2020, 33, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.C.; Thorne, A. Late adolescents’ self-defining memories about relationships. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 39, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Gregory, J. Overgeneral autobiographical memory and depression in older adults: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.N.; Cho, M.J. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric depression scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988, 24, 709–711. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-M.; Yoo, J.-A.; Bae, K.-Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Yang, S.-J.; Shin, I.-S.; Yoon, J.-S. Standardization and Validation of Big Five Inventory-Korean Version(BFI-K) in Elders. Korean J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pervin, L.A.; John, O.P. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.-H.; Park, E.-Y.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kwon, J.-H.; Cho, Y.-R.; Kim, Y. Short form of the Korean inventory of interpersonal problems circumplex scales (KIIP-SC). Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 21, 923–940. [Google Scholar]

- Alden, L.E.; Wiggins, J.S.; Pincus, A.L. Construction of circumplex scales for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. J. Personal. Assess. 1990, 55, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsford, J.; Renneberg, B. Autobiographical memories of interpersonal trust in borderline personality disorder. Bord. Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedtfeld, I.; Renkewitz, F.; Mädebach, A.; Hillmann, K.; Kleindienst, N.; Schmahl, C.; Schulze, L. Enhanced memory for negative social information in borderline personality disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedtfeld, I.; Kroneisen, M. Impaired memory for cooperative interaction partners in borderline personality disorder. Bord. Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Pincus, A.L.; DeMoor, R.M.; Koonce, E.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems–Short Circumplex (IIP–SC) with college students. J. Personal. Assess. 2008, 90, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Urbanaviciute, I.; Rossier, J. Perceived social support and Big Five personality traits in middle adulthood: A 4-year cross-lagged path analysis. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vize, C.E.; Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R. Examining the conceptual and empirical distinctiveness of Agreeableness and “dark” personality items. J. Personal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J.K. Dominance and prestige: A tale of two hierarchies. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 26, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Williams, K.M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 2002, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, J.G.; Lyons-Ruth, K. BPD’s interpersonal hypersensitivity phenotype: A gene-environment-developmental model. J. Personal. Disord. 2008, 22, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G. Process-Based CBT: The Science and Core Clinical Competencies of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, D.; Akert, R.M. Words and everything else: Verbal and nonverbal cues in social interpretation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Category | % | No. | Category | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Serious illness | 36.67 | 7 | Marriage | 23.33 |

| 2 | Having grandchildren | 36.67 | 8 | Divorce | 23.33 |

| 3 | Death of parents | 33.33 | 9 | Baptism | 20.00 |

| 4 | Spousal bereavement | 26.67 | 10 | Socializing with peers | 20.00 |

| 5 | First job | 26.67 | 11 | Earning money for the first time | 20.00 |

| 6 | Brothers/sisters | 23.33 | 12 | Procreation | 20.00 |

| Variables | Mean (Range) or % | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 71.50 (65–79) | 3.72 |

| Gender (female; %) | 63 | |

| Education (year) | 7.31 (0–20) | 4.15 |

| Period of living alone (year) | 18.23 (1–47) | 10.77 |

| MMSE-DS | 26.73 (20–30) | 2.24 |

| SGDS | 3.09 (0–9) | 2.73 |

| Indexes | Kappa | p |

|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.66 | 0.000 |

| CF | 0.61 | 0.000 |

| Dominance index | 0.62 | 0.000 |

| Warmth index | 0.62 | 0.000 |

| Indexes | D1 | D2 | D3 | W1 | W2 | W3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dm | 0.65 * | 0.61 * | 0.45 * | - | - | - |

| Wm | - | - | - | 0.74 * | 0.70 * | 0.75 * |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RF | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. CF | 0.37 ** | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Dm | −0.01 | 0.21 * | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Wm | −0.09 | −0.68 ** | 0.03 | - | |||||||||

| 5. A | −0.07 | −0.30 * | −0.23 * | 0.19 | - | ||||||||

| 6. PA | 0.19 | 0.35 ** | 0.11 | −0.19 | −0.62 ** | - | |||||||

| 7. BC | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.28 * | 0.36 ** | - | ||||||

| 8. DE | −0.07 | 0.24 * | −0.01 | −0.21* | −0.14 | 0.18 | 0.65 ** | - | |||||

| 9. FG | 0.04 | 0.25 * | −0.03 | −0.25* | −0.31 * | 0.34 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.70 ** | - | ||||

| 10. HI | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.06 | −0.10 | −0.31 * | 0.19 | 0.57 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.55 ** | - | |||

| 11. JK | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.15 | 0.35 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.51 ** | - | ||

| 12. LM | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.47 ** | 0.28 * | 0.36 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.75 ** | - | |

| 13. NO | 0.11 | 0.42 ** | 0.21 * | −0.17 | −0.39 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.21 * | 0.21 * | 0.41 ** | 0.18 | 0.50 ** | 0.50 ** | - |

| Mean | 2.56 | 0.90 | −0.56 | 0.63 | 44.61 | 9.00 | 11.88 | 13.53 | 11.45 | 14.24 | 13.37 | 13.96 | 10.30 |

| Sd | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 1.21 | 4.35 | 2.47 | 2.97 | 3.69 | 3.13 | 3.56 | 3.28 | 2.94 | 4.35 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwan, Y.; Choi, S.; Eom, T.R.; Kim, T.H. Development of a Structured Interview to Explore Interpersonal Schema of Older Adults Living Alone Based on Autobiographical Memory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052316

Kwan Y, Choi S, Eom TR, Kim TH. Development of a Structured Interview to Explore Interpersonal Schema of Older Adults Living Alone Based on Autobiographical Memory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052316

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwan, Yunna, Sungwon Choi, Tae Rim Eom, and Tae Hui Kim. 2021. "Development of a Structured Interview to Explore Interpersonal Schema of Older Adults Living Alone Based on Autobiographical Memory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052316

APA StyleKwan, Y., Choi, S., Eom, T. R., & Kim, T. H. (2021). Development of a Structured Interview to Explore Interpersonal Schema of Older Adults Living Alone Based on Autobiographical Memory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052316