The Epidemiology of Injuries in Adults in Nepal: Findings from a Hospital-Based Injury Surveillance Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Development and Evaluation of the Surveillance Model

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

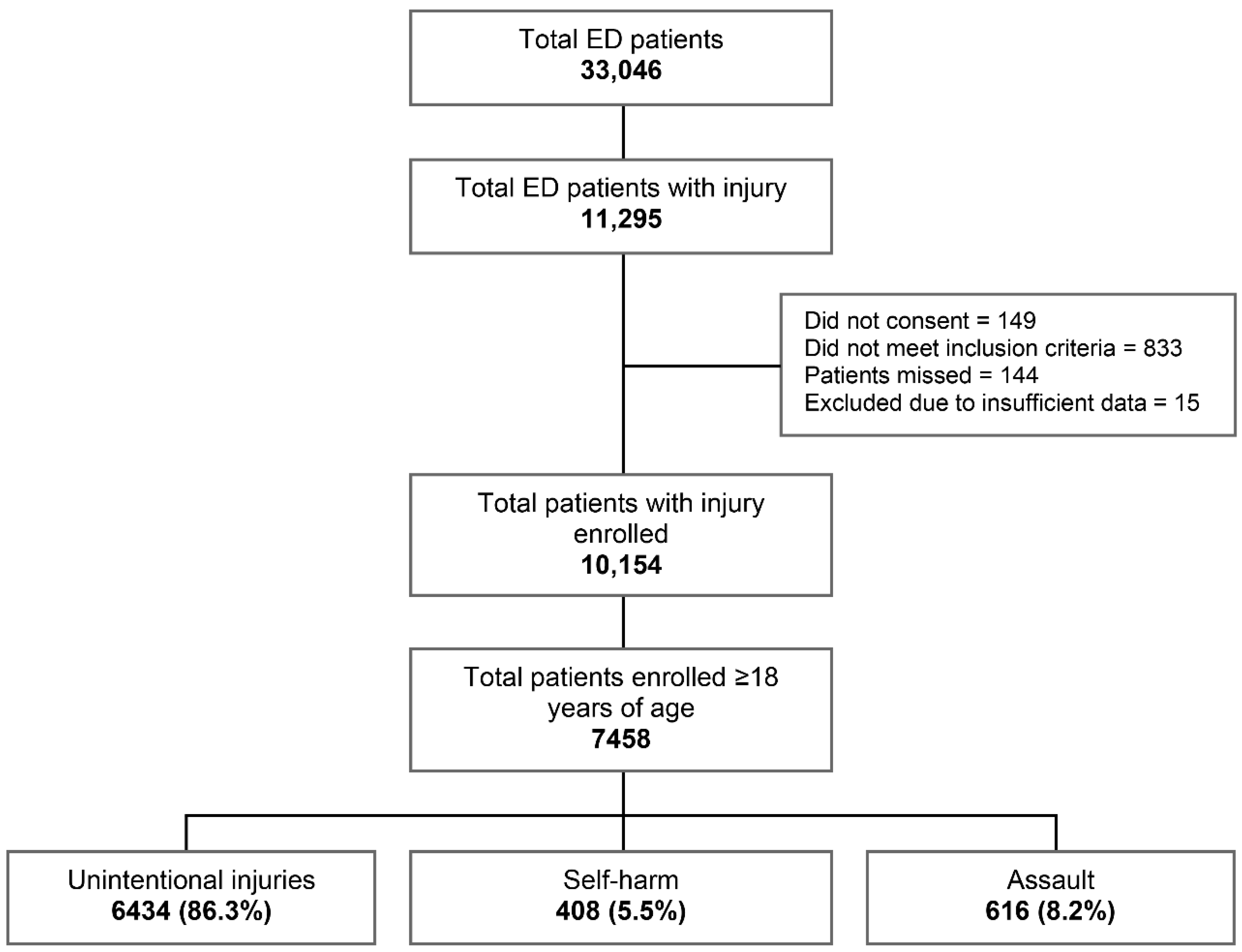

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology of Adult Injuries

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Mechanism of Injury by Age and Sex

3.1.3. Association between Demographics and Injury Severity

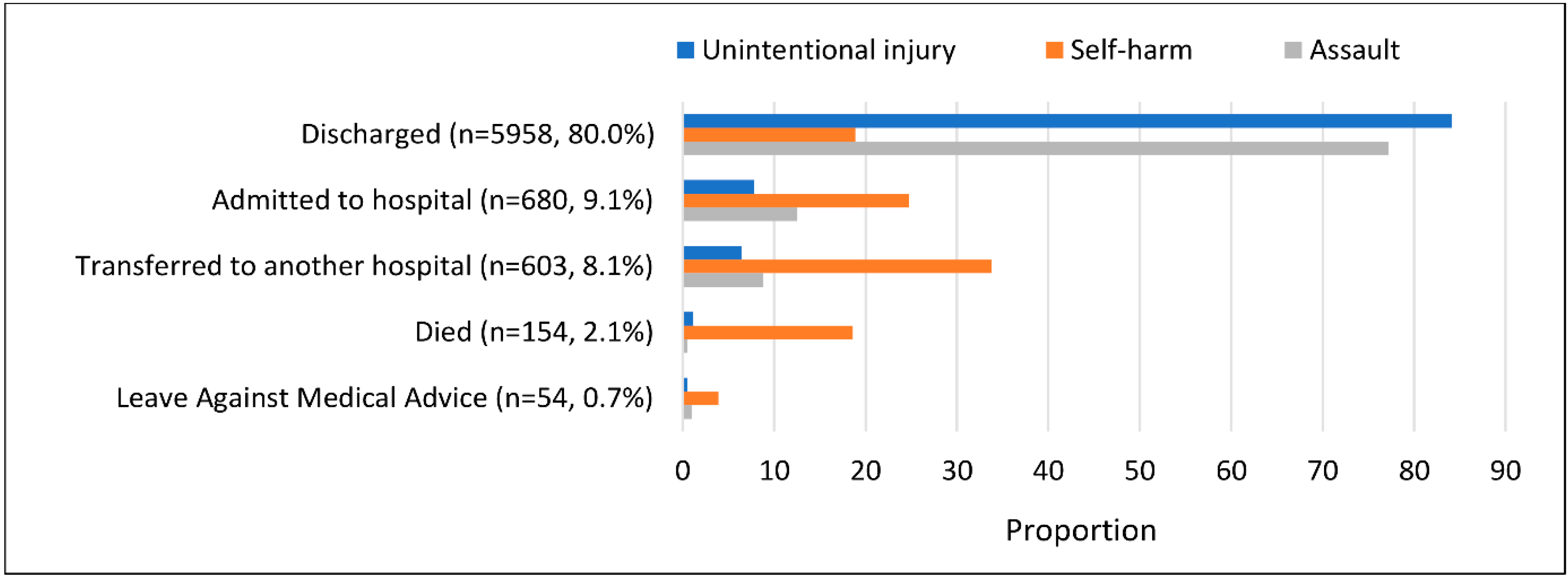

3.1.4. Outcomes of Injury

3.2. Findings of the Process Evaluation

Injury data collection work might be difficult for clinical staff in the existing system. They might feel huge pressure if it is being added to their responsibilities. It might be difficult for them to treat the patient and collect the data at the same time.(Data collector, female, Hetauda Hospital)

Many patients visit the emergency department, and sometimes it is extremely busy. Most of the time, only two clinical staff are on duty to provide emergency care. If they [clinical staff] are required to collect data in such a situation, they will not have enough time to do so.(Data collector, female, Chure Hill Hospital)

The government has not provided additional funding for this [injury surveillance] programme. The government only budgets for its own programmes, and each programme has its own staff.(Paramedic, male, Hetauda Hospital)

I really like this programme. This is the first time such a programme has been conducted here. We would be able to learn about the number of injury incidents and the circumstances surrounding them. Similarly, we would know how to improve our emergency care services.(ED nurse, female, Chure Hill Hospital)

There are ten doctors in this hospital, and only a few of them are familiar with injury surveillance. Others who are uninterested in injury surveillance are unaware of the importance of data and how data collectors are performing their work.(Senior doctor, male, Chure Hill Hospital)

If the surveillance system is a government programme overseen by the Ministry of Health, it must be managed by the hospital. All of the staff will follow the system as if it were their own programme … Injury surveillance in all hospitals is possible if it is led by a higher authority, such as the government or a ministry.(Senior doctor, male, Hetauda Hospital)

Having these data collectors with medical knowledge was extremely beneficial to us. They assist us in the morning and evening, in busy hours, and during emergencies, which is a good thing.(Senior doctor, male, Hetauda Hospital)

Data collection has become simple because the data collectors come from a medical background. It would have been difficult for them if they did not come from a medical background. Because our subject is injury, it is simple for medical background staff to collect data.(Study team member, female, MIRA/NIRC)

We have sought assistance from police officers on occasion. Police officers, like us, are required to record cases such as road traffic injuries. They do not, however, have to collect information as thoroughly as we do.(Data collector, female, Chure Hill Hospital)

In the mortuary case, police introduce our data collectors to the deceased person’s relative and request them to provide information. It has simplified things.(ED nurse, male, Hetauda Hospital)

I enjoyed collecting data on tablets. Because of the functionality of the REDCap software, it is simple to collect data.(Data collector, female, Hetauda Hospital)

Yes, some of the cases have been missed. It usually happens when a large number of patients present at the emergency department at the same time. Sometimes serious injury cases are immediately referred to another hospital, and we are not aware of these cases because we are busy collecting data on other cases. We only knew about those cases while going through the register.(Data collector, female, Hetauda Hospital)

Collecting data with the relative of a deceased person is quite a difficult task, as they are in shock. Additionally, the relatives of a deceased person leave immediately after post-mortem. They do not wait for us.(Study team member, female, MIRA/NIRC)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Injuries and Violence: The Facts 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, R.A.; Spiegel, D.A.; Coughlin, R.; Zirkle, L.G. Injuries: The neglected burden in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Vos, T.; Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Flaxman, A.D.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2012, 380, 2197–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, P.R.; Banstola, A.; Bhatta, S.; Mytton, J.A.; Acharya, D.; Bhattarai, S.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dhungana, G.P.; Dingels, Z.V.; et al. Burden of injuries in Nepal, 1990–2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Inj. Prev. 2020, 26, i57–i66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G. Leading Causes of Mortality from Diseases and Injury in Nepal: A Report from National Census Sample Survey. J. Inst. Med. 2006, 28, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.-W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-Cause and cause-Specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Neupane, D.; Bhandari, P.M.; Khanal, V.; Kallestrup, P. Burgeoning burden of non-communicable diseases in Nepal: A scoping review. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.; Shrestha, S.; Kayastha, S.; Parajuli, N.; Dhoju, D.; Shrestha, D. A comparative study on epidemiology, spec-trum and outcome analysis of physical trauma cases presenting to emergency department of Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University Hospital and its outreach centers in rural area. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2013, 11, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.; Shrestha, P.K.; Wasti, H.; Kadel, T.; Ghimire, P.; Dhungana, S. A review of violent and traumatic deaths in Kathmandu, Nepal. Int. J. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2006, 13, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banstola, A.; Kigozi, J.; Barton, P.; Mytton, J. Economic Burden of Road Traffic Injuries in Nepal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytton, J.; Bhatta, S.; Thorne, M.; Pant, P. Understanding the burden of injuries in Nepal: A systematic review of published studies. Cogent Med. 2019, 6, 1673654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, D.; Bhatta, S.; Mytton, J.; Joshi, E.; Bird, E.L.; Bhatta, S.; Manandhar, S.R.; Joshi, S.K. Establishing injury surveillance in emergency departments in Nepal: Protocol for mixed methods prospective study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, Y.; Peden, M.; Krug, E.; Lund, J.; Gururaj, G.; Kobusingye, O. Injury Surveillance Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nwomeh, B.C.; Lowell, W.; Kable, R.; Haley, K.; Ameh, E.A. History and development of trauma registry: Lessons from developed to developing countries. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2006, 1, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cassidy, L.D.; Olaomi, O.; Ertl, A.; Ameh, E.A. Collaborative Development and Results of a Nigerian Trauma Registry. J. Regist. Manag. 2016, 43, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, K.A.; Paruk, F.; Bachani, A.M.; Wesson, H.H.; Wekesa, J.M.; Mburu, J.; Mwangi, J.M.; Saidi, H.; Hyder, A.A. Establishing hospital-based trauma registry systems: Lessons from Kenya. Injury 2013, 44, S70–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, P.V.M.; Tripathy, J.P.; Tripathy, N.; Singh, S.; Bhatia, D.; Jagnoor, J.; Kumar, R. A pilot study of a hospital-based injury surveillance system in a secondary level district hospital in India: Lessons learnt and way ahead. Inj. Epidemiol. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainiqolo, I.; Kafoa, B.; Kool, B.; Herman, J.; McCaig, E.; Ameratunga, S. A profile of injury in Fiji: Findings from a popula-tion-based injury surveillance system (TRIP-10). BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkrantz, L.; Schuurman, N.; Arenas, C.; Nicol, A.; Hameed, M.S. Maximizing the potential of trauma registries in low-income and middle-income countries. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2020, 5, e000469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowafi, H.; Ngaruiya, C.; O’Reilly, G.; Kobusingye, O.; Kapil, V.; Rubiano, A.M.; Ong, M.; Puyana, J.C.; Rahman, A.F.; Jooma, R. Emergency care surveillance and emergency care registries in low-income and middle-income countries: Conceptual challenges and future directions for research. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. 6), e001442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatta, S.; Pant, P.R.; Mytton, J. Usefulness of hospital emergency department records to explore access to injury care in Nepal. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laytin, A.D.; Azazh, A.; Girma, B.; Debebe, F.; Beza, L.; Seid, H.; Landes, M.; Wytsma, J.; Reynolds, T.A. Mixed methods process evaluation of pilot implementation of the African Federation for Emergency Medicine trauma data project protocol in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 9, S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home, D. 24th (Final) Report of the Home and Leisure Accident Surveillance System: 2000, 2001 and 2002 Data; Department of Trade and Industry: London, UK, 2003.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DoHS. Health Management Information System-Guideline 2017; Department of Health Services (DoHS), Goverment of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 12; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, D.; Bhatta, S.; Mytton, J.; Joshi, E.; Bhatta, S.; Manandhar, S.; Joshi, S. Epidemiology of paediatric injuries in Nepal: Evidence from emergency department injury surveillance. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, S.; Hickford, A.; McIlroy, R.; Turner, J.; Bachani, A.M. Road Safety in Low-Income Countries: State of Knowledge and Future Directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, P.R.; Deave, T.; Banstola, A.; Bhatta, S.; Joshi, E.; Adhikari, D.; Manandhar, S.R.; Joshi, S.K.; Mytton, J.A. Home-related and work-related injuries in Makwanpur district, Nepal: A household survey. Inj. Prev. 2021, 27, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Panta, P.P.; Amgain, K. An Epidemiological Study of Injuries in Karnali, Nepal. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock 2020, 13, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- CBS. Population Monograph of Nepal Vol II (Social Demography); Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014.

- Sigdel, M.R.; Raut, K.B. Wasp bite in a referral hospital in Nepal. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2013, 11, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.P.; Vohra, R.; Stalcup, P.; Shrestha, B.R. A season of snakebite envenomation: Presentation patterns, timing of care, anti-venom use, and case fatality rates from a hospital of southcentral Nepal. J. Venom Res. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pantha, S.; Subedi, D.; Poudel, U.; Subedi, S.; Kaphle, K.; Dhakal, S. Review of rabies in Nepal. One Health 2020, 10, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapaliya, S.; Sharma, P.; Upadhyaya, K. Suicide and self harm in Nepal: A scoping review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2018, 32, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahatta, K.; Samuel, R.; Sharma, P.; Dixit, L.; Shrestha, B.R. Suicide burden and prevention in Nepal: The need for a national strategy. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2017, 6, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagaman, A.K.; Maharjan, U.; Kohrt, B.A. Suicide surveillance and health systems in Nepal: A qualitative and social net-work analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Population. Hospital Based One-Stop Crisis Management Center (OCMC) Operational Manual 2067; Ministry of Health and Population, Goverment of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011.

| Age and Sex | Total | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | n | Rate/1000 (95% CI) | n | Rate/1000 (95% CI) | n | Rate/1000 (95% CI) |

| 18–29 | 2950 | 32.6 (31.5–33.8) | 2048 | 48.6 (46.6–50.7) | 902 | 18.7 (17.5–19.9) |

| 30–44 | 2378 | 32.0 (30.8–33.3) | 1524 | 42.8 (40.7–44.9) | 854 | 22.1 (20.6–23.5) |

| 45–59 | 1285 | 26.4 (25.0–27.9) | 778 | 31.1 (28.9–33.2) | 507 | 21.5 (19.7–23.4) |

| 60 & above | 845 | 25.7 (24.0–27.4) | 459 | 27.9 (25.4–30.4) | 386 | 23.5 (21.2–25.8) |

| Total | 7458 | 30.3 (29.6–31.0) | 4809 | 40.4 (39.2–41.5) | 2649 | 20.9 (20.0–21.7) |

| Median (IRQ *) | 33 years (25–47 years) | 32 years (24–45 years) | 36 years (26–50 years) | |||

| Age Groups, Sex Intent, and Mechanisms | 18–29 Years | 30–44 Years | 45–59 Years | ≥60 Years | Total | Male | Female | Male-to-Female Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | n (rate/1000) | M:F | |

| Unintentional | ||||||||

| Road traffic injury | 1005 (11.1) | 686 (9.2) | 291 (6.0) | 130 (4.0) | 2112 (8.6) | 1628 (13.7) | 484 (3.8) | 3.4:1 |

| Fall | 460 (5.1) | 504 (6.8) | 339 (7.0) | 332 (10.1) | 1635 (6.6) | 847 (7.1) | 788 (6.2) | 1.1:1 |

| Animal/insect-related | 408 (4.5) | 396 (5.3) | 288 (5.9) | 201 (6.1) | 1293 (5.3) | 700 (5.9) | 593 (4.7) | 1.2:1 |

| Stabbed, cut, or pierced | 279 (3.1) | 215 (2.9) | 108 (2.2) | 47 (1.4) | 649 (2.6) | 493 (4.1) | 156 (1.2) | 3.2:1 |

| Injured by a blunt object | 209 (2.3) | 157 (2.1) | 55 (1.1) | 46 (1.4) | 467 (1.9) | 374 (3.1) | 93 (0.7) | 4.0:1 |

| Poisoning † | 28 (0.3) | 23 (0.3) | 11 (0.2) | 10 (0.3) | 72 (0.3) | 35 (0.3) | 37 (0.3) | 0.9:1 |

| Electrocution | 35 (0.4) | 17 (0.2) | 6 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 63 (0.3) | 40 (0.3) | 23 (0.2) | 1.7:1 |

| Fire, burn, or scald | 18 (0.2) | 16 (0.2) | 15 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | 59 (0.2) | 33 (0.3) | 26 (0.2) | 1.3:1 |

| Suffocation or choking | 5 (0.1) | 15 (0.2) | 9 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | 33 (0.1) | 18 (0.2) | 15 (0.1) | 1.2:1 |

| Other | 16 (0.2) | 20 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 51 (0.2) | 28 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) | 1.2:1 |

| Total | 2463 (27.3) | 2049 (27.6) | 1132 (23.3) | 790 (24.0) | 6434 (26.1) | 4196 (35.2) | 2238 (17.6) | 1.9:1 |

| Self-harm | ||||||||

| Poisoning ‡ | 138 (1.5) | 82 (1.1) | 41 (0.8) | 18 (0.5) | 279 (1.1) | 100 (0.8) | 179 (1.4) | 0.6:1 |

| Hanging | 21 (0.2) | 19 (0.3) | 13 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 59 (0.2) | 32 (0.3) | 27 (0.2) | 1.2:1 |

| Stabbed, cut, or pierced | 40 (0.4) | 11 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 54 (0.2) | 40 (0.3) | 14 (0.1) | 2.9:1 |

| Other | 9 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) | 4 (0.0) | 3.0:1 |

| Total | 208 (2.3) | 118 (1.6) | 58 (1.2) | 24 (0.7) | 408 (1.7) | 184 (1.5) | 224 (1.8) | 0.8:1 |

| Assault | ||||||||

| Bodily force | 206 (2.3) | 167 (2.2) | 69 (1.4) | 21(0.6) | 463 (1.9) | 321 (2.7) | 142 (1.1) | 2.3:1 |

| Injured by a blunt object | 36 (0.4) | 27 (0.4) | 14 (0.3) | 6(0.2) | 83 (0.3) | 57 (0.5) | 26 (0.2) | 2.2:1 |

| Stabbed, cut, or pierced | 29 (0.3) | 14 (0.2) | 12 (0.2) | 4(0.1) | 59 (0.2) | 45 (0.4) | 14 (0.1) | 3.2:1 |

| Other | 8 (0.1) | 3 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0(0.0) | 11 (0.0) | 6 (0.1) | 5 (0.0) | 1.2:1 |

| Total | 279 (3.1) | 211 (2.8) | 95 (2.0) | 31(0.9) | 616 (2.5) | 429 (3.6) | 187 (1.5) | 2.3:1 |

| Characteristics | Minor or No Apparent Injury (Total = 4551) n (%) | Moderate or Severe Injury (Total = 2897) n (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2886 (60.1) | 1915 (39.9) | 1.35 (1.20–1.52) | 0.000 |

| Female | 1665 (62.9) | 982 (37.1) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Age groups (years) | ||||

| 18–29 | 1819 (61.7) | 1128 (38.3) | 1.25 (1.03–1.51) | 0.024 |

| 30–44 | 1465 (61.7) | 910 (38.3) | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) | 0.190 |

| 45–59 | 778 (60.6) | 506 (39.4) | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) | 0.730 |

| ≥60 | 489 (58.1) | 353 (41.9) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Ethnicity/caste * | ||||

| Dalit | 198 (55.8) | 157 (44.2) | 1.33 (1.06–1.67) | 0.014 |

| Janajati | 2061 (58.5) | 1465 (41.5) | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) | 0.000 |

| Madhesi | 253 (57.9) | 184 (42.1) | 1.26 (1.02–1.56) | 0.031 |

| Muslim | 102 (62.2) | 62 (37.8) | 1.01 (0.73–1.41) | 0.935 |

| Brahmin/Chhetri | 1845 (65.6) | 967 (34.4) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Others | 84 (58.7) | 59 (41.3) | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) | 0.198 |

| Education ** | ||||

| No formal education | 1446 (55.2) | 1175 (44.8) | 1.70 (1.41–2.05) | 0.000 |

| Primary school | 1257 (62.0) | 772 (38.0) | 1.19 (1.00–1.41) | 0.048 |

| Secondary school | 1065 (65.8) | 554 (34.2) | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 0.720 |

| Post-secondary school | 781 (67.3) | 380 (32.7) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Occupation *** | ||||

| Mainly unemployed | 1064 (57.6) | 783 (42.4) | 1.51 (1.20–1.90) | 0.000 |

| Employed salaried | 1101 (63.6) | 629 (36.4) | 1.20 (0.96–1.49) | 0.094 |

| Daily wage earners | 809 (60.1) | 538 (39.9) | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | 0.523 |

| Agricultural labourer | 681 (59.1) | 472 (40.9) | 1.23 (0.96–1.58) | 0.109 |

| Business owner | 467 (62.8) | 277 (37.2) | 1.19 (0.93–1.53) | 0.167 |

| Student | 385 (68.6) | 176 (31.4) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Pensioner | 44 (75.9) | 14 (24.1) | 0.69 (0.36–1.33) | 0.265 |

| Participant Number | Interview Participant’s Role in Hospital/Study | Based | Gender | Age (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Data collector | Chure Hill Hospital | Female | 20–25 |

| P2 | Data collector | Chure Hill Hospital | Female | 20–25 |

| P3 | Data collector | Hetauda Hospital | Female | 35–40 |

| P4 | Data collector | Hetauda Hospital | Female | 20–25 |

| P5 | ED nurse | Chure Hill Hospital | Female | 30–35 |

| P6 | Senior nurse | Chure Hill Hospital | Female | 25–30 |

| P7 | Manager | Chure Hill Hospital | Male | 25–30 |

| P8 | Senior doctor | Chure Hill Hospital | Male | 30–35 |

| P9 | Manager | Hetauda Hospital | Male | 40–45 |

| P10 | Senior doctor | Hetauda Hospital | Male | 45–50 |

| P11 | ED nurse | Hetauda Hospital | Male | 40–45 |

| P12 | Paramedic | Hetauda Hospital | Male | 55–60 |

| P13 | Study team member | MIRA/NIRC | Female | 40–45 |

| P14 | Study team member | MIRA/NIRC | Male | 45–50 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhatta, S.; Magnus, D.; Mytton, J.; Joshi, E.; Bhatta, S.; Adhikari, D.; Manandhar, S.R.; Joshi, S.K. The Epidemiology of Injuries in Adults in Nepal: Findings from a Hospital-Based Injury Surveillance Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312701

Bhatta S, Magnus D, Mytton J, Joshi E, Bhatta S, Adhikari D, Manandhar SR, Joshi SK. The Epidemiology of Injuries in Adults in Nepal: Findings from a Hospital-Based Injury Surveillance Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312701

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhatta, Santosh, Dan Magnus, Julie Mytton, Elisha Joshi, Sumiksha Bhatta, Dhruba Adhikari, Sunil Raja Manandhar, and Sunil Kumar Joshi. 2021. "The Epidemiology of Injuries in Adults in Nepal: Findings from a Hospital-Based Injury Surveillance Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312701

APA StyleBhatta, S., Magnus, D., Mytton, J., Joshi, E., Bhatta, S., Adhikari, D., Manandhar, S. R., & Joshi, S. K. (2021). The Epidemiology of Injuries in Adults in Nepal: Findings from a Hospital-Based Injury Surveillance Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312701