Abstract

We investigated the association between the frequency of laughter and lifestyle diseases after the Great East Japan Earthquake. We included 41,432 participants aged 30–89 years in the Fukushima Health Management Survey in fiscal year 2012 and 2013. Gender-specific, age-adjusted and multivariable odds ratios of lifestyle diseases were calculated using logistic regressions stratified by evacuation status. Those who laugh every day had significantly lower multivariable odds ratios for hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM) and heart disease (HD) for men, and HT and dyslipidemia (DL) for women compared to those who do not, especially in male evacuees. The multivariable odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of HT, DM and HD (non-evacuees vs. evacuees) for men were 1.00 (0.89–1.11) vs. 0.85 (0.74–0.96), 0.90 (0.77–1.05) vs. 0.77 (0.64–0.91) and 0.92 (0.76–1.11) vs. 0.79 (0.63–0.99), and HT and DL for women were 0.90 (0.81–1.00) vs. 0.88 (0.78–0.99) and 0.80 (0.70–0.92) vs. 0.72 (0.62–0.83), respectively. The daily frequency of laughter was associated with a lower prevalence of lifestyle disease, especially in evacuees.

1. Introduction

Scholars have recently reported the health benefits of daily laughter. Previous studies have shown that laughter is associated with a lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease [1] and may decrease the risk of such diseases [2]. Experimental studies have also demonstrated that laugher moderates stress, improves the immune system [3,4], decreases allergic responses [5], reduces the increase in postprandial blood glucose in patients with diabetes mellitus [6] and improves blood vessel function [7]. Moreover, an increasing number of interventional studies have revealed positive effects of laughter on depression, insomnia, self-rated health and hemoglobin A1c levels [8,9,10].

The Great East Japan Earthquake and the subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011 constituted one of the most destructive catastrophes in Japan to date. Due to radiation concerns, most residents in nearby towns had to evacuate and, consequently, suffered long-lasting anxiety. Shortly after the disaster, the Fukushima Health Management Survey was launched [11,12]. Similar to previous studies [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], the survey’s results showed that after the disaster, the prevalence of people with cardiovascular risk factors [26]—including overweight [27], hypertension [28], diabetes mellitus [29], dyslipidemia [30] and metabolic syndrome [31]—increased among community residents. At the same time, as in previous studies [32] or even more, community residents exhibited psychological distress [33,34,35], particularly among evacuees [26,36].

The favorable effects of laughter on health may be associated with better health even after this disaster. Recently, the positive effects of laughter on human health have been recognized [37,38], and scholars have suggested that the lack of positive factors may be a more critical determinant to develop lifestyle diseases than the presence of negative factors. For example, previous studies have shown that depression on mortality and functional decline might result from the absence of positive factors rather than the presence of negative ones [39,40]. To our knowledge, the effects of laughter on lifestyle diseases after a disaster have not been examined. There may be a strong association between laughter and lifestyle-related diseases under high-stress conditions, such as evacuation due to a disaster. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the association between the frequency of laughter as a positive psychological factor and lifestyle diseases after the Great East Japan Earthquake based on the hypothesis that the prevalence of lifestyle-related diseases is lower in the group who laugh every day and that the association may be particularly strong among those who experienced evacuation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

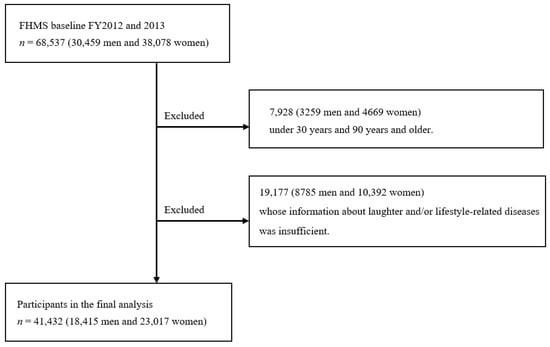

The Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey was a part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey started after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. The Fukushima Health Management Survey is a large cohort study that monitors the long-term health of residents in Fukushima Prefecture after the earthquake and promotes their future well-being. The details of this survey are described elsewhere [11,12]. The subjects of the survey were officially registered as residents of the evacuation zone designated by the government (including those who evacuated or moved to other prefectures) between 11 March 2011 and 1 April 2012, regardless of their age. The areas included Hirono Town, Naraha Town, Tomioka Town, Kawauchi Village, Okuma Town, Futaba Town, Namie Town, Katsurao Village, Minamisoma City, Tamura City, Kawamata Town, Iitate Village and a part of Date City. We targeted all residents of the evacuation areas in the survey. Questionnaires were mailed to residents in January 2012, 2013 and 2014, and the deadline for responses was set at six months. Out of the 68,537 respondents of the data of fiscal year 2012 and 2013, we excluded 7928 people under the age of 30 and over the age of 89. We also excluded 19,117 people who had a lack of information on the frequency of laughter and/or the diagnosis of lifestyle-related diseases. Ultimately, 41,432 respondents were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The survey participants were informed in writing; the results were totaled and reported after analysis, and only those who returned the self-recorded questionnaire were considered to have provided consent to participate in the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fukushima Medical University (#1316, #2148 and IPPAN 2020-239).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant selection for the present study. Association between laughter and lifestyle diseases after the Great East Japan Earthquake: The Fukushima Health Management Survey.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Frequency of Laughter

We assessed the daily frequency of laughter by a single question, “How often do you laugh out loud?”. Possible responses included “almost every day”, “1–5 days per week”, “1–3 days per month”, and “almost never”. This variable was dichotomized. Those who responded “almost every day” were categorized as people who laugh every day, and those who responded otherwise were categorized as people who do not laugh every day. This measurement has been used in previous studies in Japan [1,41], and reliability was also assessed in this study.

2.2.2. Lifestyle Diseases

We assessed the lifestyle diseases of cancer, stroke, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia via questionnaires. A single question was, “Have you ever been diagnosed with [a disease]?” The respondents answered either “Yes” or “No”.

2.2.3. Experience of Evacuation

We asked the question, “How have you changed your living condition as a result of the earthquake?” to check the experience of evacuation of participants. Possible answers were “evacuation shelter”, “temporary housing”, “rental house/apartment”, “relative’s house”, “owned house”, or “other”. Those who answered, “evacuation shelter” and “temporary housing” were defined as people who had experienced evacuation. For those without this information, we asked “Where do you currently live?”. Possible answers were “municipally subsidized rental housing”, “temporary housing”, “restoration public housing”, “rented house/apartment”, “relative’s house”, “owned house”, and “other”. Those who answered, “Municipally subsidized rental housing”, “Temporary housing”, “Restoration public housing”, were defined as people who had experienced evacuation; that is, they changed their living environment that would affect their lives more after the disaster.

2.2.4. Lifestyle Factors

We obtained data on height and weight by the questionnaire, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Smoking status was obtained and categorized into current and non-smokers, including past smokers. The alcohol consumption was determined and categorized into current drinkers (more than once a month) and non-drinkers, including past drinkers. Physical activity status was obtained by a single question, “Do you usually do exercise?” Possible answers included “almost every day”, “2–4 times per week”, “once a week”, and “almost never”. The respondents’ quality of sleep was assessed by asking a single question, “Are you satisfied with the quality of your sleep over the past month (regardless of sleep duration)?”. On the questionnaire, possible answers were “Satisfied”, “Slightly dissatisfied”, “Quite dissatisfied”, and “Very dissatisfied or haven’t slept at all”.

2.2.5. Other Variables

The patient’s subjective health was assessed by a single question, “How is your current health condition?” and possible answers were “very good”, “good”, “normal”, “bad”, and “very bad”. Those who answered, “very good”, “good”, and “normal”, were categorized as having a better subjective health. Psychological distress was assessed using the Japanese version of the Kessler 6 (K6) scale [42,43], and those with a score of ≥ 13 were defined as having psychological distress. Cronbach’s alpha for K6 was 0.92 [43,44,45]. Trauma reactions were also assessed by the Japanese version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist–Stressor-Specific Version (PCL-S) [46,47,48]. A total score of ≥ 44 was classified as a sign of probable PTSD. Cronbach’s alpha for PCL-S was 0.96 [46,49]. Job status was assessed by asking a single question, “Please tell us about your current work style” and possible answers were “full-time”, “part-time”, and “unemployed”. Connection with others was assessed by “How many (1. relatives or siblings or 2. friends) do you have that you can talk to about personal matters without hesitation?” and “How many (1. relatives or siblings or 2. friends) do you feel close to that you can ask for help?” and possible answers were “0”, “1”, “2”, “3–4”, “5–8”, and “more than 9”.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The gender-specific characteristics of the respondents were described according to the categories of the frequency of laughter. Multiple analyses were conducted for those who laugh 1–5 days per week, 1–3 days per month, almost never compared to those who laugh every day according to each factor. We derived the p-values for the trend analysis from a regression model for continuous variables, and a logistic model for dichotomized variables according to the categories of laughter adjusted by age. Using logistic regressions, we calculated gender-specific, age-adjusted odds ratios, multivariable odds ratios, and the 95% confidence interval of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cancer, stroke, or heart disease for those who laugh almost every day compared to those who do not. The same analyses were performed and stratified by the presence or absence of an evacuation experience. The covariates included age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), smoking status (non-smoker, current smoker, or missing), drinking status (current drinker, non-drinker, or missing), habitual physical activity (almost every day, 2–4 times per week, about once a week, almost never, or missing), quality of sleep (satisfied, somewhat unsatisfied, highly unsatisfied, very unsatisfied or could not sleep, or missing), mental health distress (yes, no, or missing), job status (full-time, part-time, unemployed, or missing), connection with others (one or more closer friend or relatives, or missing) for the analysis of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, and history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia (yes, no, or missing) in addition to other variables for the analysis of stroke, heart disease or cancer. We used the SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) for all statistical analyses. All probability values for statistical tests were two-tailed and p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

Among the 41,432 individuals, 6383 (34.6%) men and 6286 (27.3%) women reported hypertension, 2410 (13.1%) men and 1567 (6.8%) women for diabetes mellitus, 2604 (13.1%) men and 3169 (13.8%) women for dyslipidemia, 776 (4.2%) men and 514 (2.2%) women for cancer, 370 (2.0%) men and 213 (0.9%) women for stroke, and 1597 (8.7%) men and 1349 (5.9%) women for heart disease. Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants according to the frequency of daily laughter. The proportion of those who laugh almost every day was 23.1% in men and 28.6% in women. The proportion of those who experienced evacuation was 47.1% in men and 48.2% in women. Compared to those who laugh every day, those who do not laugh every day were older, had lower BMI, had lower prevalence of habitual alcohol drinker and physical activity, better subjective health, full-time job, had higher prevalence of smoker, unsatisfied sleep quality, mental health distress, traumatic symptom, and experience of evacuation in men; and were older, had lower prevalence of habitual alcohol drinker and physical activity, better subjective health, full-time job, and higher prevalence of smoker, unsatisfied sleep quality, mental health distress, traumatic symptom, and experience of evacuation in women (p for trend < 0.01).

Table 1.

Gender-specific means and proportions of characteristics for participants according to the frequency of laughter.

3.2. Associations between Frequency of Laughter and Lifestyle Diseases

Table 2 shows the gender-specific association between the frequency of laughter and lifestyle diseases. For men, compared to those who do not laugh every day, the participants who laugh every day had lower age and gender-adjusted odds ratios for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and heart disease. Those associations remained statistically significant even after adjusting for other related variables of lifestyle and diseases like diabetes mellitus and heart disease. The multivariable odds ratios were 0.84 (0.75–0.94) for diabetes mellitus and 0.86 (0.75–1.00) for heart disease. In women, the participants who laugh every day had lower age and gender-adjusted odds ratios for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, stroke and heart disease compared to those who do not. This association remained statistically significant even after adjusting for other variables related to lifestyle, diseases, hypertension and dyslipidemia. The multivariable odds ratios were 0.89 (0.83–0.97) for diabetes mellitus and 0.76 (0.69–0.84) for dyslipidemia. On multivariate analysis, men who laugh every day had higher odds ratio for cancer compared to those who did not.

Table 2.

Gender-specific age-adjusted and multivariable odds ratios of lifestyle diseases for those who laugh every day compared to those who do not laugh every day.

3.3. Associations between Frequency of Laughter and Lifestyle Diseases According to Evacuation Experiences

Table 3 shows the association between the frequency of laughter and lifestyle diseases stratified by evacuation experiences. The magnitude of associations was slightly larger for evacuees with hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia compared to non-evacuees, particularly men. Moreover, an association was evident and stronger for men with heart disease with evacuation experiences compared those without. For stroke, the association was not significant in either men or women for multivariable analysis. The multivariable odds ratios for hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia for men (non-evacuees vs. evacuees) were 1.00 (0.89–1.11) vs. 0.85 (0.74–0.96), 0.90 (0.77–1.05) vs. 0.77 (0.64–0.91) and 0.95 (0.81–1.10) vs. 0.92 (0.78–1.07), respectively; for women, they were 0.90 (0.81–1.00) vs. 0.88 (0.78–0.99), 0.84 (0.70–1.01) vs. 0.93 (0.77–1.13) and 0.80 (0.70–0.92) vs. 0.72 (0.63–0.83), respectively. The multivariable odds ratios for heart disease among men (non-evacuees vs. evacuees) was 0.92 (0.76–1.11) vs. 0.79 (0.63–0.99).

Table 3.

Gender-specific age-adjusted and multivariable odds ratios of lifestyle diseases for those who laugh every day compared to those who do not laugh every day stratified by experience of evacuation.

4. Discussion

Those who experienced evacuation had a lower prevalence of those who laugh daily. Compared to those who do not laugh every day, those who laugh every day had a lower prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and heart disease after the Great East Japan Earthquake, and the magnitude of associations was larger for evacuees especially men.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between the frequency of laughter and lifestyle-related diseases stratified by evacuation experience after a large-scale disaster. So far, several studies have reported the deterioration of health status after major disasters, both physically and psychologically [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Similarly, in addition to the mental health deterioration [49], after the Great East Japan Earthquake, increases in body weight [27], hypertension [28], diabetes mellitus [29], dyslipidemia [30] and metabolic syndrome were reported [31]. Furthermore, there are few reports on the association between the daily frequency of laughter and lifestyle diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. For example, Hayashi et al. reported that the daily frequency of laughter was associated with a lower prevalence of cardiovascular diseases among a population of about 20,000 men and women aged 65 years and above [1]. In addition, Sakurada et al. investigated the association between the daily frequency of laughter and the all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease [2]. In the current study, we proved our hypothesis by showing that those who laugh every day had a lower prevalence of lifestyle-related disease that increase after a major disaster. In addition, an important point of our results is that the association might be stronger in those who experienced evacuation, particularly among men. There are many possible factors for this. After a large-scale disaster, victims’ health is threatened by a variety of issues, such as lifestyle changes, changes from loss of social community due to evacuation, loss of close relatives, disaster trauma and stress caused by these factors, which may lead to the development of lifestyle diseases. In fact, in the present study, it is shown that people who laugh less frequently were more likely to have experienced evacuation. However, laughter has been reported to have stress-reducing effects increasing physical activity, mental health benefits and improvement in other related lifestyle and social interaction [50]. These effects are considered to have enabled evacuees to prevent lifestyle-related diseases through the revival of a diminished social community, the reduction of trauma and stress, and other effects on improving lifestyle habits and mental health status. The results of this study confirm that the association between laughter and lifestyle-related diseases is weakened when adjusted for social factors. This indicates that the social connections that are generated by laughter, or, conversely, laughter that is thought to increase in frequency due to social connections, may have a close relationship with the prevention of lifestyle-related diseases. Previous studies have reported a higher risk of developing lifestyle diseases and cardiovascular disease after a major disaster in evacuees than in non-evacuees [27,28,29,30,31,36]. The value of laughter after a major disaster increases the stronger association among evacuees between laughter and lifestyle and cardiovascular disease. In the current study, we found no significant association for stroke. The results may be influenced by the lower number of people who had a stroke during the study period than that of other diseases. It is possible that the number of cases of stroke may increase after more time has passed since the disaster and an association may be found. The frequency of daily laughter has been reported to increase with social support, social networks, subjective well-being called “ikigai”, conversations with others and healthy diets including fish, beans, household items, fruits and vegetables [9,41,50,51,52]. In addition, it is becoming clear that laughter programs, such as laughter yoga and other laughter activities, also increase those favorable lifestyle choices [9]. Laughing on a daily basis and being in an environment where one can laugh during challenging situations is important for living without lifestyle diseases. In the present study, we found that men who laugh everyday were more likely to have cancer than those who do not. However, since laughing is unlikely to be a cause of cancer, we inference that many of the men with cancer may have become aware of the benefits of laughter after receiving treatment and began to incorporate laughter into their daily lives. This point needs to be explored in more detail in a longitudinal study.

We faced the following limitations of this study. First, as we conducted a cross-sectional study, the causal relationship is unclear. Therefore, we are preparing a prospective study for the next analysis. Second, in our study, lifestyle diseases and cardiovascular diseases were confirmed by self-administrated questionnaires, not measurements during health checkups, which could lead to non-differential measurement errors and attenuation of the associations. Third, the overall response rate to the questionnaires was not very high (40.7%), and there were some differences in the distribution of ages between the study sample and the target population. Therefore, the results of the study may not reflect all of the evacuation areas specified by the government.

5. Conclusions

After the Great East Japan Earthquake, daily frequency of laughter was associated with a lower prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and heart disease. The association was particularly strong among men who had experienced evacuation, suggesting that positive factors such as laughter may be effective in the prevention of lifestyle diseases under stressful conditions, such as after a major disaster. Further longitudinal or intervention studies are needed to evaluate the relevant causal relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and T.O.; methodology and formal analysis, E.E.; validation, H.N., F.H., K.O., N.F. and T.O.; investigation and data curation, T.O., M.H., A.T., K.T., M.M., S.Y., H.Y. and K.K.; resources, T.O., M.H., A.T., K.T., M.M., S.Y., H.Y. and K.K.; writing and visualization, E.E.; supervision, T.O.; project administration and funding acquisition, E.E., T.O., M.M., S.Y. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This survey was supported by the National Health Fund for Children and Adults Affected by the Nuclear Incident, by the Network-type Joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science, and by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K24261.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was approved by the Fukushima Medical University Ethics Committee (approval no. 1316, 2148).

Informed Consent Statement

A questionnaire was mailed to the participants stating the purpose of the study; by returning the questionnaire, the participants were considered to have given their written consent to participate.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the present study are not publicly available because the data from the Fukushima Health Management Survey belongs to the government of Fukushima Prefecture and can only be used within the organization.

Acknowledgments

We express our deep gratitude to the staff of the Radiation Medical Science Center for Fukushima Health Management Survey (kenkan@fmu.ac.jp (F.H.M.S.) Membership of the Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey: Masaharu Maeda, Atsushi Takahashi, Maho Momoi, Saori Goto, Tetsuya Ohira, Mitsuaki Hosoya, Michio Shimabukuro, Hirooki Yabe, Tomoaki Tamaki, Kanae Takase, Itaru Miura, Hajime Iwasa, Shuntaro Itagaki, Mayumi Harigane, Naoko Horikoshi, Seiji Yasumura and Hitoshi Ohto. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Fukushima Prefecture government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hayashi, K.; Kawachi, I.; Ohira, T.; Kondo, K.; Shirai, K.; Kondo, N. Laughter is the Best Medicine? A Cross-Sectional Study of Cardiovascular Disease among Older Japanese Adults. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 26, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurada, K.; Konta, T.; Watanabe, M.; Ishizawa, K.; Ueno, Y.; Yamashita, H.; Kayama, T. Associations of Frequency of Laughter with Risk of All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Incidence in a General Population: Findings from the Yamagata Study. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.P.; Zeller, J.M.; Rosenberg, L.; McCann, J. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2003, 9, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Iwase, M.; Yamashita, K.; Tatsumoto, Y.; Ue, H.; Kuratsune, H.; Shimizu, A.; Takeda, M. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2001, 8, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimata, H. Effect of Humor on Allergen-Induced Wheal Reactions. JAMA 2001, 285, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Iwanaga, S.; Kawai, K.; Ishii, H.; Shoji, S.; Murakami, K. Laughter lowered the increase in postprandial blood glucose. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1651–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, M.; Mangano, C.; Park, Y.; Goel, R.; Plotnick, G.D.; Vogel, R.A. Impact of cinematic viewing on endothelial function. Heart 2006, 92, 261–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.-J.; Youn, C.-H. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2011, 11, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosaki, M.; Ohira, T.; Kajiura, M.; Kiyama, M.; Kitamura, A.; Sato, S.; Iso, H. Effects of a laughter and exercise program on physiological and psychological health among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: Randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012, 13, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, M.; Mojtahed, A.; Modabbernia, A.; Mojtahed, M.; Shafiabady, A.; Delavar, A.; Honari, H. Laughter yoga versus group exercise program in elderly depressed women: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 26, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasumura, S.; Hosoya, M.; Yamashita, S.; Kamiya, K.; Abe, M.; Akashi, M.; Kodama, K.; Ozasa, K.; Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. Study Protocol for the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Mashiko, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Hisata, M.; Niwa, S.-I.; Yasumura, S.; Yamashita, S.; Kamiya, K.; Abe, M.; et al. Psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident: Results of a mental health and lifestyle survey through the Fukushima Health Management Survey in FY2011 and FY2012. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2014, 60, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, E.; Nakamura, A.; Abe, A.; Kagaya, Y.; Kohzu, K.; Sato, K.; Nakajima, S.; Fukui, S.; Endo, H.; Takahashi, T.; et al. Occurrence of Cardiovascular Events After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster. Int. Heart J. 2013, 54, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, M.; Celentano, E.; Meucci, C.; Farinaro, E.; Jossa, F.; Krogh, V.; Giumetti, D.; Panico, S.; Scottoni, A.; Mancini, M. Short-term effect of natural disasters on coronary heart disease risk factors. Arteriosclerosis 1986, 6, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; McEwen, B.S.; Pickering, T.G. Disasters and the heart: A review of the effects of earthquake-induced stress on cardiovascular disease. Hypertens Res. 2003, 26, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; Matsuo, T.; Kayaba, K.; Soukejima, S.; Kagamimori, S.; Shimada, K. Earthquake-induced cardiovascular disease and related risk factors in focusing on the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 8, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kario, K.; Matsuo, T. Increased Incidence of Cardiovascular Attacks in the Epicenter Just After the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Thromb. Haemost. 1995, 74, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kario, K.; Matsuo, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Shimada, K. Earthquake-Induced Potentiation of Acute Risk Factors in Hypertensive Elderly Patients: Possible Triggering of Cardiovascular Events After a Major Earthquake. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 29, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; Matsuo, T.; Shimada, K.; Pickering, T.G. Factors associated with the occurrence and magnitude of earthquake-induced increases in blood pressure. Am. J. Med. 2001, 111, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Miki, T.; Matsuo, T. Hanshin-Awaji earthquake and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1995, 345, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itabashi, R.; Furui, E.; Sato, S.; Yazawa, Y.; Kawata, K.; Mori, E. Incidence of Cardioembolic Stroke Including Paradoxical Brain Embolism in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 37, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohira, T.; Takeishi, Y.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Kawasaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; et al. Increased prevalence of atrial fibrillation after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 198, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Takahashi, J.; Fukumoto, Y.; Yasuda, S.; Ito, K.; Miyata, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Inoue, K.; Yagi, T.; Komaru, T.; et al. Effect of the Great East Japan earthquake on cardiovascular diseases—report from the 10 hospitals in the disaster area. Circ J. 2013, 77, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Yasuda, S.; Sakata, Y.; Ito, K.; Takahashi, J.; Miyata, S.; Tsuji, I.; Shimokawa, H. The Great East Japan Earthquake disaster and cardiovascular diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, H.; Yoshihisa, A.; Iwaya, S.; Owada, T.; Sato, T.; Suzuki, S.; Yamaki, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Kunii, H.; Nakazato, K.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients with Decompensated Heart Failure After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Nakano, H.; Nagai, M.; Yumiya, Y.; Zhang, W.; Uemura, M.; Sakai, A.; Hashimoto, S.; Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. Changes in Cardiovascular Risk Factors After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2017, 29, 47S–55S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Ozasa, K.; et al. Effect of Evacuation on Body Weight after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 50, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Ozasa, K.; et al. Evacuation and risk of hypertension after the Great East Japan earthquake: The Fukushima health management survey. Hypertension 2016, 68, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, H.; Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Sakai, A.; Watanabe, T.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, A.; Kobashi, G.; et al. Corrigendum to “Evacuation after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident Is a Cause of Diabetes: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey”. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 415253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, H.; Ohira, T.; Nagai, M.; Hosoya, M.; Sakai, A.; Watanabe, T.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, A.; et al. Hypo-high-density Lipoprotein Cholesterolemia Caused by Evacuation after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Intern. Med. 2016, 55, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hashimoto, S.; Nagai, M.; Fukuma, S.; Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; et al. Influence of Post-disaster Evacuation on Incidence of Metabolic Syndrome. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2017, 24, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neria, Y.; Olfson, M.; Gameroff, M.J.; Wickramaratne, P.; Gross, R.; Pilowsky, D.J.; Blanco, C.; Manetti-Cusa, J.; Lantigua, R.; Shea, S.; et al. The mental health consequences of disaster-related loss: Findings from primary care one year after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Psychiatry 2008, 71, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, D.; Susukida, R.; Usuda, K.; Yamanouchi, Y. Psychological distress among people in Fukushima prefecture before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake using a nation-wide survey. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Shigemura, J.; Takahashi, Y.; Nomura, S.; Yoshino, A.; Tanigawa, T. Perceived Workplace Interpersonal Support Among Workers of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants Following the 2011 Accident: The Fukushima Nuclear Energy Workers’ Support (NEWS) Project Study. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 12, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orui, M.; Ueda, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Maeda, M.; Ohira, T.; Yabe, H.; Yasumura, S. The Relationship between Starting to Drink and Psychological Distress, Sleep Disturbance after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, H.; Ohira, T.; Nagai, M.; Hosoya, M.; Sakai, A.; Yasumura, S.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, A.; et al. Evacuation is a risk factor for diabetes development among evacuees of the Great East Japan earthquake: A 4-year follow-up of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 45, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Mortality: A Quantitative Review of Prospective Observational Studies. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Cohen, S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G.; Hybels, C.F. What symptoms of depression predict mortality in community-dwelling elders? J. Am. Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52, 2052–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosaki, M.; Ishimoto, Y.; Kasahara, Y.; Konno, A.; Kimura, Y.; Fukutomi, E.; Chen, W.; Nakatsuka, M.; Fujisawa, M.; Sakamoto, R.; et al. Positive affect as a predictor of lower risk of functional decline in community-dwelling elderly in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012, 13, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Kawachi, I.; Ohira, T.; Kondo, K.; Shirai, K.; Kondo, N. Laughter and subjective health among community-dwelling older people in Japan cross-sectional analysis of the Japan gerontological evaluation study cohort data. J. Nerv. Ment. Disord. 2015, 203, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H.; et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.-L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunii, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Shiga, T.; Yabe, H.; Yasumura, S.; Maeda, M.; Niwa, S.-I.; Otsuru, A.; Mashiko, H.; Abe, M.; et al. Severe Psychological Distress of Evacuees in Evacuation Zone Caused by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, E.B.; Jones-Alexander, J.; Buckley, T.C.; Forneris, C.A. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yabe, H.; Horikoshi, N.; Yasumura, S.; Kawakami, N.; Ohtsuru, A.; Mashiko, H.; Maeda, M.; on behalf of the Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Diagnostic accuracy of Japanese posttraumatic stress measures after a complex disaster: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 2016, 9, e12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Shiga, T.; Maeda, M.; Yabe, H.; Yasumura, S.; Niwa, O.; Matsui, S.; Ohira, T.; Mashiko, H.; et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Japanese version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist in community dwellers following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant incident: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. SAGE Open. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yabe, H.; Yasumura, S.; Ohira, T.; Niwa, S.-I.; Ohtsuru, A.; Mashiko, H.; Maeda, M.; Abe, M.; on behalf of the Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Psychological distress and the perception of radiation risks: The Fukushima health management survey. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosaki, M.; Fukushima Health Management Survey Group; Ohira, T.; Yasumura, S.; Maeda, M.; Yabe, H.; Harigane, M.; Takahashi, H.; Murakami, M.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Lifestyle factors and social ties associated with the frequency of laughter after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Fukushima Health Management Survey. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 27, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, E.; Saito, I.; Maruyama, K.; Mori, H.; Tanno, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; Nishioka, S.; Kinoshita, T.; Tomooka, K.; et al. Lifestyle habits that increase laughter: To on health study. In Proceedings of the 73rd Japanese Society of Public Health, Tochigi, Japan, 5–7 November 2014; Volume 213. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, M.; Eguchi, E.; Sakano, N.; Kubo, M.; Nagaoka, K.; Ogino, K. The association between diet and laughter: Ibara study. Jpn. Soc. Hyg. 2016, 71, S199. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).