A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

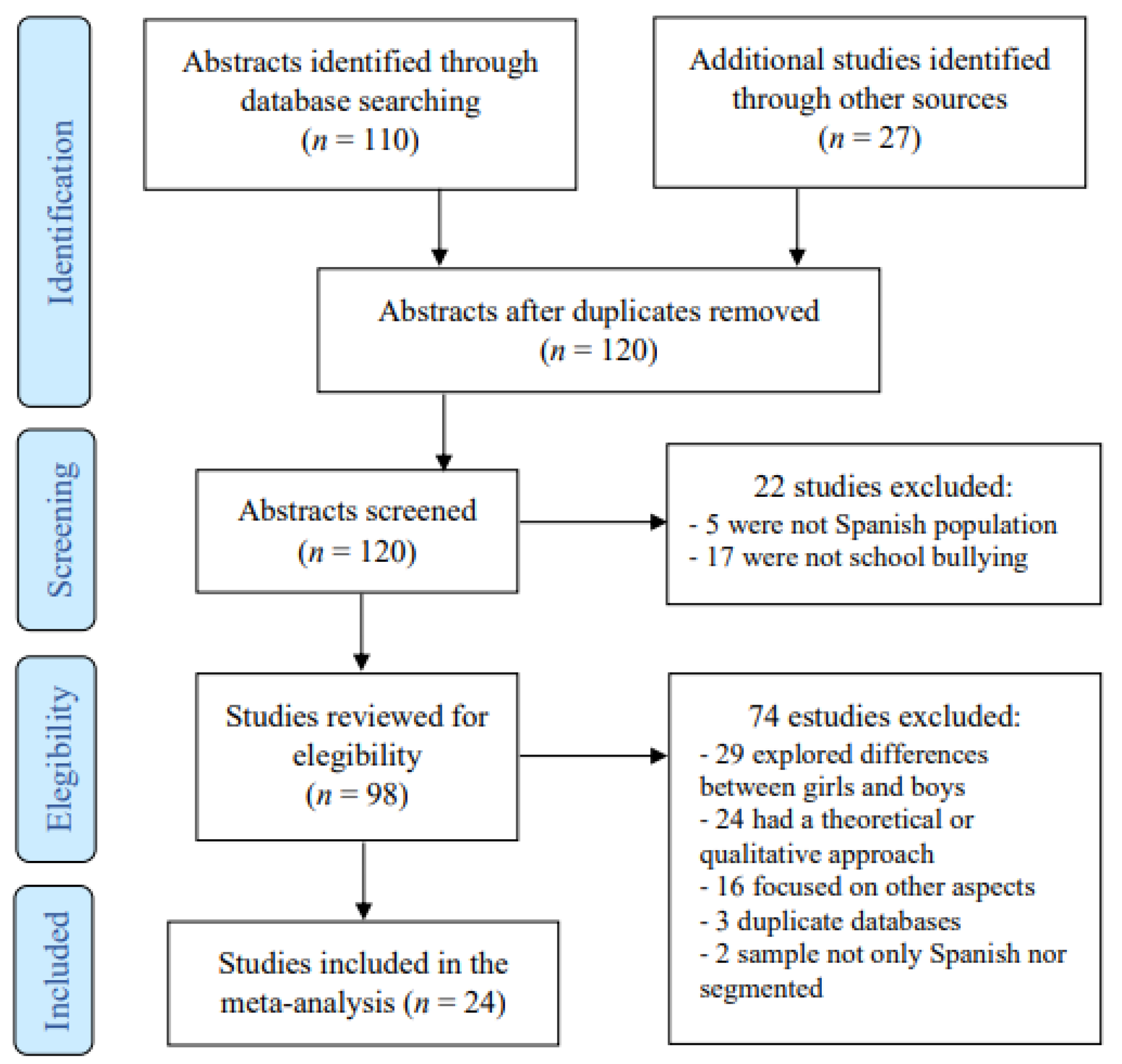

2. Materials and Methods

| STUDY | REGION | SAMPLE | SAMPLE AGE & SEX | INSTRUMENT | TIME FRAME | FREQUENCY | RATE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gualdi et al., 2008 [31] | Madrid | 152 students | Not reported | Self-reported item | Last academic year | At least once | 73% victimisation |

| 2. Garchitorena, 2009 [32] | Whole Spain | 325 LGBT+ students | = 20.9; 45.5% girls | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 56.8% victimisation |

| 3. INJUVE, 2011 [33] | Whole Spain | 1411 participants | Between 15 and 29; 49% girls | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 75% observation |

| 4. Generelo, 2012 [34] | Whole Spain | 653 LGBT+ students | Under 25; 34% girls | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 71% victimisation |

| 5. López et al., 2013 [16] | Whole Spain | 762 LGBT+ participants | Different ages; 41% women | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 76% victimisation |

| 6. Pichardo et al., 2013 [13] | Madrid and Canary Islands | 4636 students | Between 11 and 19 50.21% girls | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 16% victimisation 30.5% perpetration 83.2% observation |

| 7. FELGTB, 2013 [35] | Whole Spain | 1000 LGBT+ students | Not reported | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 65.3% victimisation |

| 8. Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014 [36] | Basque Country | 119 LGBT+ students | Different ages; 26.89% women | Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire | Last two months | At least once | 30.25% victimisation |

| 9. Pichardo et al., 2015 [18] | Madrid, Canary Islands and Andalusia | 3236 students | Age not reported 47.1% girls | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 12% victimisation |

| 10. Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR, 2016 [37] | Whole Spain | 550 victims | Not reported | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 2.7% victimisation |

| 11. Benítez-Deán, 2016 [38] | Community of Madrid | 5605 students | Secondary students (age not reported), 49.07% girls | Self-reported items | Whole lifetime | At least once | 3.04% victimisation 59.68% observation |

| 12. Sastre et al., 2016 [19] | Whole Spain | 21,487 students | Between 12 and 16 years 48.3% girls | EBIPQ and ECIPQ | Last two months | At least once per week | 0.3% victimisation 0.32% perpetration |

| 13. Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR, 2017 [39] | Whole Spain | 365 victims | Not reported | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 2.9% victimisation |

| 14. Generalitat Valenciana, 2017 [40] | Valencian Community | 2484 victims | Not reported | Bullying reports intervened by school management teams | 2015–2016 school year | At least once | 5.39% victimisation |

| 15. Gutiérrez-Barroso & Pérez-Jorge, 2017 [41] | Canary Islands | 3723 students | Secondary students (age not reported), 50% girls | Self-reported item | Last year | At least once | 14.7% victimisation 5.9% perpetration |

| 16. Elipe et al., 2018 [42] | Andalusia | 69 LGBT+ students | Not reported for LGBT+ subsample (Overall: = 14.9, 49.4% girls) | EBIPQ | Last two months | At least once per week | 45.4% victimisation |

| 17. Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR, 2018 [43] | Whole Spain | 247 victims | Not reported | Self-reported item | Whole lifetime | At least once | 3.2% victimisation |

| 18. Orue & Calvete, 2018 [44] | Basque Country | 791 students | = 13.96 years 43.61% girls | Escala de acoso escolar homofóbico | Last month | At least once | 79% observation 23.2% perpetration |

| 19. Aparicio-García et al., 2018 [45] | Whole Spain | 233 LGBT+ students | Not reported for LGBT+ subsample (Overall between 14 and 25 years) | Self-reported items | Whole lifetime | At least once | 42.9% victimisation |

| 20. Kualitate Lantaldea & ALDARTE, 2018 [46] | Basque Country | 107 LGBT+ participants | Not reported | Self-reported items | Whole lifetime | At least once | 45% victimisation |

| 21. Albaladejo-Blázquez et al., 2019 [47] | Valencian Community | 1723 students | = 13.39 years 49% girls | The Homophobic Verbal Content Bullying of HCAT | Last week | Three or more times | 25.31% victimisation 29.48% perpetration |

| 22. Rodríguez-Hidalgo & Hurtado-Mellado, 2019 [48] | Andalusia | 820 students | = 14.87 years 51.7% girls | Homophobic EBIPQ | Last two months | At least once per week | 23% victimisation |

| 23. Martínez-Gómez et al., 2019 [49] | Valencian Community | 87 students | = 13,34 years 50.6% girls | Escala de Vivencias de discriminación | Whole lifetime | At least once | 13% victimisation 10.4% perpetration 89.5% observation |

| 24. Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020 [50] | Basque Country | 219 LGBT+ students | Not reported for LGBT+ subsample (Overall: between 13 and 17 years, 52.6% girls) | Escala de Screening de acoso entre iguales | Whole lifetime | At least several times | 25.1% victimisation |

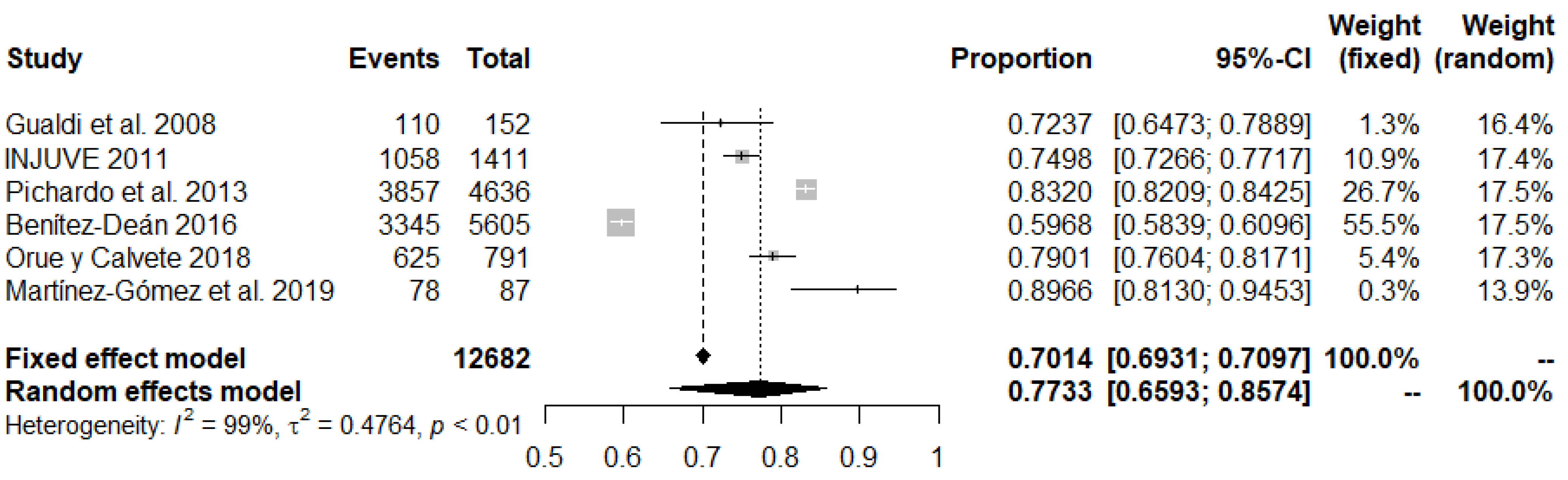

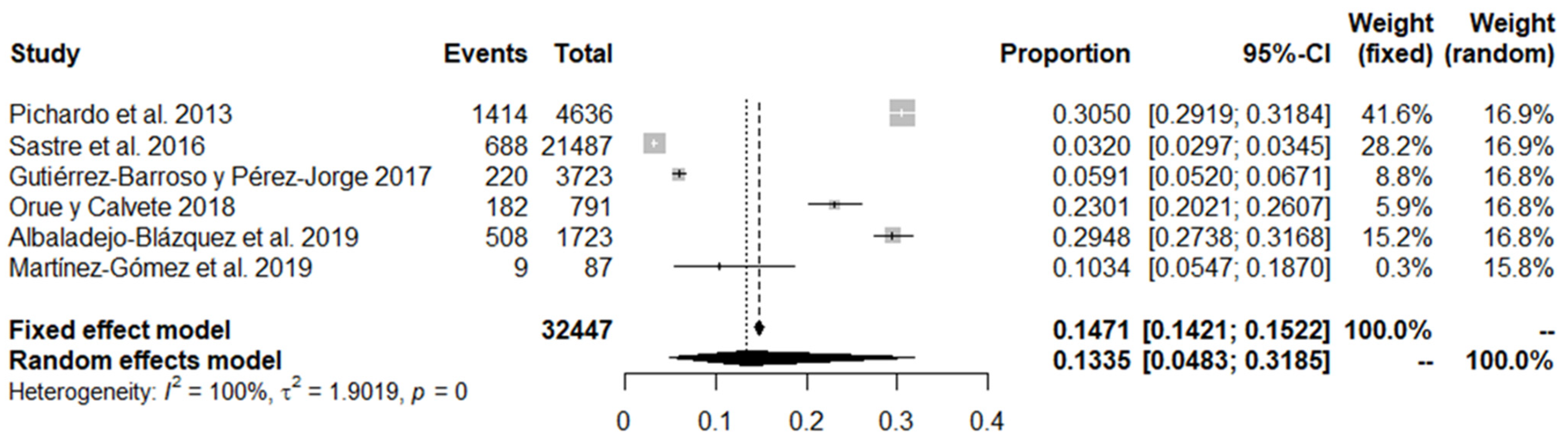

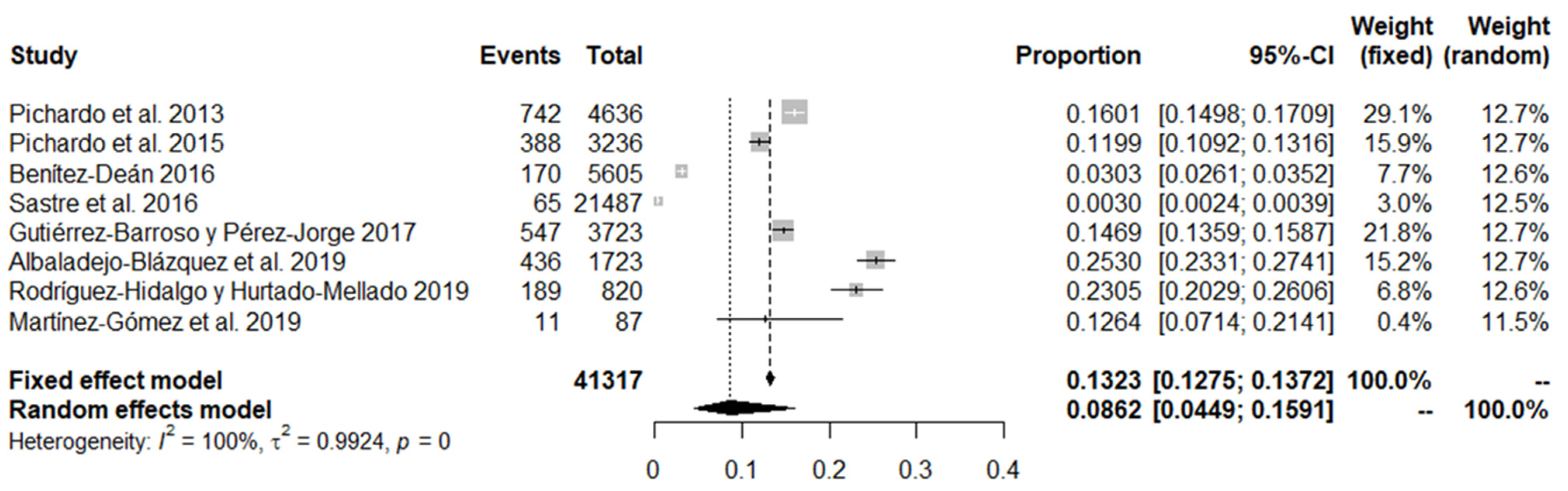

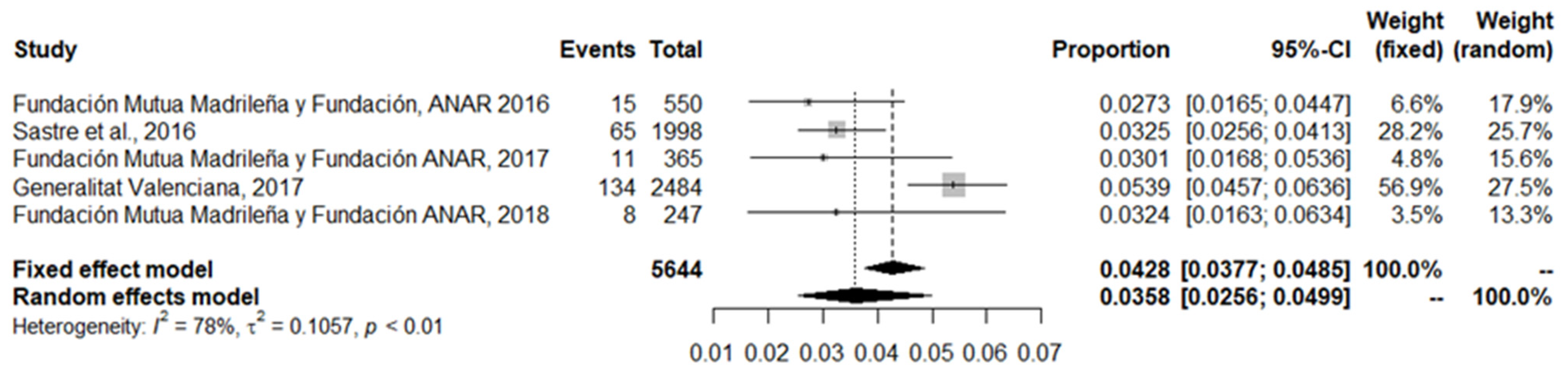

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins Norman, J. Homophobic Bullying in Irish Secondary Education; Academica Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Moore, M. Understanding School Bullying. A Guide for Parents and Teachers; Veritas: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M. Systematic Review: Bullying Involvement of Children with and without Chronic Physical Illness and/or Physical/Sensory Disability—A Meta-Analytic Comparison with Healthy/Nondisabled Peers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platero, L.; Gómez, E. Herramientas para Combatir el Bullying Homofóbico; Talasa: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017; Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/ss/pdfs/ss6708a1-h.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Vaillancourt, T.; Brittain, H.; Krygsman, A.; Farrell, A.H.; Landon, S.; Pepler, D. School bullying before and during COVID-19: Results from a population-based randomized design. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platero, L. La homofobia como elemento clave del acoso escolar homofóbico. Algunas voces desde Rivas Vaciamadrid. Inf. Psicol. 2008, 94, 71–83. Available online: http://www.informaciopsicologica.info/previous_issues.php (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Ruiz, A.; Evangelista, A.; Xolocotzi, A. ¿Cómo llamarle a lo que tiene muchos nombres? ¿Bullying, violencia de género, homofobia o discriminación contra personas LGBTI? Rev. Interdiscip. Estud. Género Col. México 2018, 4, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Hacer la Vista… ¡Gorda! El Acoso Escolar en España, un Asunto de Derechos Humanos; Amnistía Internacional España: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/ficherosoia/documentos/5836_d_Informe-Amnistia_Acoso-Escolar-2019.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Blaya, C.; Debarbieux, E.; Lucas Molina, B. La violencia hacia las mujeres y hacia otras personas percibidas como distintas a la norma dominante: El caso de los centros educativos. Rev. Educ. 2007, 342, 61–81. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/revista-de-educacion/inicio.html (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de Diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral Contra la Violencia de Género. Boletín Off. Estado 2004, 313. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2004-21760 (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Molinuevo Puras, B.; Rodríguez Medina, P.O.; Romero López, M. Actitudes Ante la Diversidad Sexual de la Población Adolescente de Coslada (Madrid) y San Bartolomé de Tirajana (Gran Canaria); FELGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Generelo Lanaspa, J.; Pichardo Galán, J.I. Homofobia en el Sistema Educativo; Comisión de Educación de COGAM: Madrid, Spain, 2006; Available online: http://www.felgtb.org/rs/466/d112d6ad-54ec-438b-93584483f9e98868/807/filename/homofobia-en-el-sistema-educativo.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Rainbow Europe. Available online: https://rainbow-europe.org/country-ranking (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- López, A.; Generelo, J.; Arroyo, A. Estudio 2013 Sobre Discriminación por Orientación Sexual y/o Identidad de Género en España; FELTGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: http://www.felgtb.org/rs/2447/d112d6ad-54ec-438b-9358-4483f9e98868/bd2/filename/estudio-2013-sobre-discriminacion-por-orientacion-sexual-y-o-identidad-de-genero-en-espana.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Maroto, A.L. Homosexualidad y Trabajo Social. Herramientas para la Reflexión e Intervención Profesional; Siglo XXI Editores España: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo Galán, J.I.; de Stéfano Barbero, M.; Sánchez Sainz, M.; Puche Cabezas, L.; Molinuevo Puras, B.; Moreno Cabrera, O. Diversidad Sexual y Convivencia: Una Oportunidad Educativa; Universidad Complutense de Madrid & FELGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre, A.; Calmaestra, J.; Escorial, A.; García, P.; Del Moral, C.; Perazzo, C.; Ubrich, T. Yo a Eso no Juego. Bullying y Ciberbullying en la Infancia; Save the Children España: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/yo_a_eso_no_juego.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, J.; Gambara, H. Qué es el Meta-Análisis; Biblioteca Nueva: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Botella, J.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Meta-Análisis en Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud; Editorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martxueta, A. Consecuencias del bullying homofóbico retrospectivo y los factores psicosociales en el bienestar psicológico de sujetos LGB. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2014, 32, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orue, I.; Calvete, E.; Fernández-González, L. Adaptación de la “Escala de acoso escolar homofóbico” y magnitud del problema en adolescentes españoles. Psicol. Conduct. 2018, 26, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, E.; Garaigordobil, M. El Bullying en el País Vasco: Prevalencia y Diferencias en Función del Sexo y la Orientación-Sexual. Clín. Salud 2020, 31, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.C.; Pigott, T.D.; Rothstein, H.R. How Many Studies Do You Need? A Primer on Statistical Power for Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2010, 35, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metaphor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vevea, J.L.; Coburn, K.M. Maximum-likelihood methods for meta-analysis: A tutorial using R. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2015, 18, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi, M.; Martelli, M.; Wilhelm, W.; Biedrón, R.; Graglia, M.; Pietrantoni, L. Schoolmates. Bullying Homofóbico en las Escuelas. Guía para Profesores; Programa Daphne II: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Available online: www.educatolerancia.com (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Garchitorena, M. Informe Jóvenes LGTB; Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales & FELGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2009. Available online: http://felgtb.com/stopacosoescolar/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Informe-jovenes-lgtbred.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Instituto de la Juventud [INJUVE]. Jóvenes y Diversidad Sexual; INJUVE: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Available online: http://www.injuve.es/observatorio/salud-y-sexualidad/jovenes-y-diversidad-sexual (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Generelo, J. Acoso Escolar Homofóbico y Riesgo de Suicidio en Adolescentes y Jóvenes LGB; FELGTB & COGAM: Madrid, Spain, 2012; Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=3645 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Federación Estatal de Lesbianas, Gais, Trans y Bisexuales [FELGTB]. Acoso Escolar (y Riesgo de Suicidio) por Orientación Sexual e Identidad de Género: Fracaso del Sistema Educativo; FELGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=3999 (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Martxueta, A.; Etxeberria, J. Análisis diferencial retrospectivo de las variables de salud mental en lesbianas, gais y bisexuales (lgb) víctimas de bullying homofóbico en la escuela. Rev. Psicopatología Psicol. Clínica 2014, 19, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación Ayuda a Niños y Adolescentes en Riesgo [ANAR]. I Estudio Sobre Sobre Acoso Escolar y Cyberbullying Según los Afectados; Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.anar.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/INFORME-I-ESTUDIO-BULLYING.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Benítez-Deán, E. LGBT-Fobia en las Aulas 2015. ¿Educamos en la Diversidad Afectivo-Sexual? Grupo de Educación del Colectivo de Lesbianas, Gays, Transexuales y Bisexuales de Madrid [COGAM]: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.bienestaryproteccioninfantil.es/fuentes1.asp?sec=32&subs=319&cod=2706&page (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Fundación Mutua Madrileña y Fundación ANAR. II Estudio Sobre Acoso Escolar y Cyberbullying Según los Afectados. Informe del Teléfono ANAR; Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR: Madrid, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://www.anar.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/INFORME-II-ESTUDIO-CIBERBULLYING.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Generalitat Valenciana. Memòria Anual—Convivència Escolar en la Comunitat Valenciana. Curs 2015–2016; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencian, Spain, 2017. Available online: http://www.ceice.gva.es/es/web/convivencia-educacion/inicio/-/asset_publisher/fQo9KePNfRG4/content/publicada-la-memoria-anual-sobre-la-convivencia-escolar-en-la-comunitat-valenciana (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Gutiérrez-Barroso, J.; Pérez-Jorge, D. Análisis del Acoso Escolar en Gran Canaria (AAEGC): Prevalencia en Educación Primaria y Secundaria 2017; Cabildo de Gran Canaria. Consejería de Recursos Humanos, Organización, Educación y Juventud: Canary Island, Spain, 2017; Available online: http://www.grancanariajoven.es/contenido/Analisis-de-la-prevalencia-del-acoso-escolar-en-Gran-Canaria-AAEGC-Prevalencia-en-educacion-primaria-y-secundaria-2017/2090 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Elipe, P.; Muñoz, M.; Del Rey, R. Homophobic Bullying and Cyberbullying: Study of a Silenced Problem. J. Homosex. 2018, 65, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR. III Estudio Sobre Acoso Escolar y Cyberbullying Según los Afectados. Informe del Teléfono ANAR; Fundación Mutua Madrileña & Fundación ANAR: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.anar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/III-Estudio-sobre-acoso-escolar-y-ciberbullying-seg%C3%BAn-los-afectados.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Orue, I.; Calvete, E. Homophobic Bullying in Schools: The Role of Homophobic Attitudes and Exposure to Homophobic Aggression. School Psych. Rev. 2018, 47, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, M.E.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; López-Núñez, M.I.; García-Nieto, I. Health and Well-Being of Cisgender, Transgender and Non-Binary Young People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kualitate Lantaldea & ALDARTE-Centro de Atención a Gais, Lesbianas y Personas Trans. Diagnóstico Sobre las Realidades de la Población LGTBI en Vitoria-Gasteiz; Servicio de Igualdad, Departamento de Alcaldía y Relaciones Institucionales, Ayuntamiento de Vitoria-Gasteiz: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2018. Available online: http://salutsexual.sidastudi.org/es/registro/a53b7fb3673c3a9f016876150ec403c1 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Albaladejo-Blázquez, N.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Delvecchio, E.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health of Adolescents Involved in School Bullying and Homophobic Verbal Content Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A.J.; Hurtado-Mellado, A. Prevalence and psychosocial predictors of homophobic victimization among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Gómez, N.; Giménez-García, C.; Enrique-Nebot, J.; Elipe-Miravet, M.; Ballester-Arnal, R. Discriminación LGBTI en las Aulas. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 1, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Larrain, E. Acoso y ciberacoso en adolescentes LGTB: Prevalencia y efectos en la salud mental. Comunicar 2020, 62, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H.; Sutton, A.J.; Borenstein, M. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessments and Adjustments; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Martínez-Valderrey, V.; Aliri, J. Victimización, percepción de la violencia y conducta social. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2014, 37, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, S.; Banister, E. (Eds.) What a Difference Sex and Gender Make: A Gender, Sex and Health Research Casebook; Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2199670 (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: Rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoso-Vázquez, T.; Rubio, M.J.; Vilà, R. Las ciberagresiones en función del género [Gendered cyber-aggressions]. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2017, 35, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barco, B.L.; Castaño, E.F.; Bullón, F.F.; Carroza, T.G. Cyberbullying en una muestra de estudiantes de educación secundaria: Variables moduladoras y redes sociales. Rev. Electron. Investig. Psicoeduc. Psigopedag. 2012, 10, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olweus, D.; Limber, S.P. Some problems with cyberbullying research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 19, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Cauich, J.I. Prevalencia del bullying en Mexico: Un meta-análisis del bullying tradicional y cyberbullying. Divers. Perspect. Psicol. 2019, 15, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S. A meta-analysis of the outcomes of bullying prevention programs on subtypes of traditional bullying victimization: Verbal, relational, and physical. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 55, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Marín-López, I. Cyberbullying: A systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicol. Educ. 2016, 22, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feijóo, S.; Rodríguez-Fernández, R. A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312687

Feijóo S, Rodríguez-Fernández R. A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312687

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeijóo, Sandra, and Raquel Rodríguez-Fernández. 2021. "A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312687

APA StyleFeijóo, S., & Rodríguez-Fernández, R. (2021). A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312687