Effectiveness of a Sexuality Workshop for Nurse Aides in Long-Term Care Facilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sexuality of Elderly Residents

1.2. Nurse Aides’ Attitudes toward Elderly Sexual Expression

1.3. Sexuality Education for Nurse Aides

2. Material and Methods

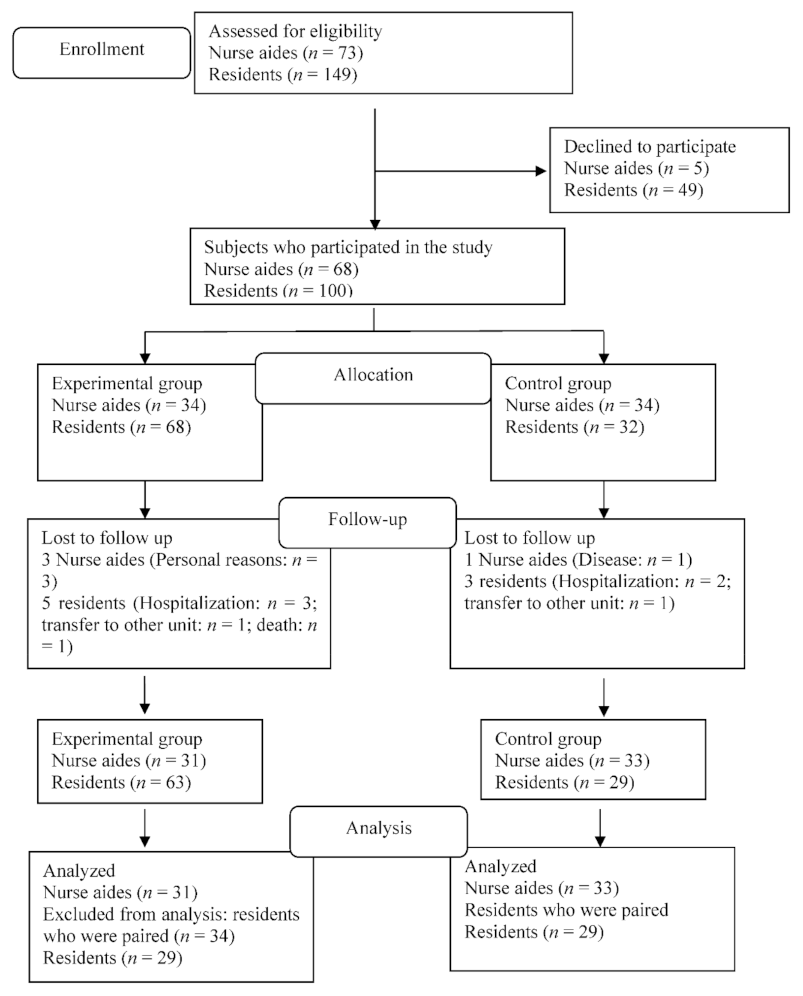

2.1. Study Site and Recruitment

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. Sexuality Workshop

2.5.2. Sexual Knowledge and Attitude Scale for Nurse Aides (SKAS-NA) in Long-Term Care Facilities

2.5.3. Quality of Sexual Life Questionnaire for Residents (QSL-R) in Long-Term Care Facilities

2.6. Analysis of Data

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Demographic Data of the Subjects

3.1.1. Demographic Data of the Nurse Aides

3.1.2. Demographic Data of the Residents

3.2. Change in Sexual Knowledge Scores of the Nurse Aides

3.3. Change in Sexual Attitude Scores of the Nurse Aides

3.4. Effect of the Sexuality Workshop on Residents’ Quality of Sexual Life

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, M.; Fetherstonhaugh, D.; Tarzia, L.; Nay, R.; Wellman, D.; Beattie, E. ‘I always look under the bed for a man’. Needs and barriers to the expression of sexuality in residential aged care: The views of residents with and without dementia. Psychol. Sex. 2013, 4, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochlainn, L.M.; Kenny, R.A. Sexual activity and aging. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnaud, T.; Sirvain, S.; Igier, V.; Taiton, M. A study of hidden sexuality in elderly people living in institutions. Sexologies 2013, 22, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, P.; Shuttleworth, R.; Pratt, J.; Block, H.; Rammler, L. Disability, sexuality and intimacy. In Politics of Occupation-Centred Practice: Reflections on Occupational Engagement across Cultures, 1st ed.; Pollard, N., Skellariou, D., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 162–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, J. Sexual consent capacity: Ethical issues and challenges in long-term care. Clin. Gerontol. 2017, 40, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrklund, K.; Taskinen, S.; Rintala, R.J.; Pakarinen, M.P. Sexual function, fertility and quality of life after modern treatment of anorectal malformations. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Pinto, J.M.; Wroblewski, K.E.; McClintock, M.K. Sensory dysfunction and sexuality in the U.S. population of older adults. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.X.; Tsai, L.Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.L. Sexual health care during course of disease. J. Taiwan-Nurse Pract. 2017, 3, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, D. Psychosocial barriers to sexual intimacy for older people. Br. J. Nurs. 2014, 23, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellard, J.; Rodgers, C.; Bales, A.L. Balancing sexual expression and risk of harm in elderly persons with dementia. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2017, 45, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Helmes, E.; Chapman, J. Education about sexuality in the elderly by healthcare professionals: A survey from the Southern Hemisphere. Sex Educ. 2012, 12, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelison, L.J.; Doll, G.M. Management of sexual expression in long-term care: Ombudsmen’s perspectives. Gerontologist 2012, 53, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simpson, P.; Wilson, C.B.; Brown, L.J.E.; Dickinson, T.; Horne, M. The challenges and opportunities in researching intimacy and sexuality in care homes accommodating older people: A feasibility study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bauer, M.; Haesler, E.; Fetherstonhaugh, D. Let’s talk about sex: Older people’s views on the recognition of sexuality and sexual health in the health-care setting. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.; Horne, M.; Brown, L.J.E.; Wilson, C.B.; Dickinson, T.; Torkington, K. Old(er) care home residents and sexual/intimate citizenship. Ageing Soc. 2017, 37, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tenenbaum, E. To be or to exist: Standards for deciding whether dementia patients in nursing homes should engage in intimacy, sex, and adultery. Indiana Law Rev. 2009, 42, 675–721. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrott, M.D.; Margrett, J.A. Taking a person-centered approach to understanding sexual expression among long-term care residents: Theoretical perspectives and research challenges. Ageing Int. 2011, 36, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, H. Older people in care homes: Sexuality and intimate relationships. Nurs. Older People 2011, 23, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinke, E.E.; Jaarsma, T. Sexual counseling and cardiovascular disease: Practical approaches. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 17, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E.; Wu, A.M.S.; Ho, P.; Pearson, V. Older Chinese men and women’s experiences and understanding of sexuality. Cult. Health Sex. 2011, 13, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.S.Y.; Jackson, S.; Cao, S.; Kwok, C. Sex with Chinese characteristics: Sexuality research in/on 21st-century China. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 486–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; McAuliffe, L.; Nay, R.; Chenco, C. Sexuality in older adults: Effect of an education intervention on attitudes and beliefs of residential aged care staff. Educ. Gerontol. 2013, 39, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Lin, Y.C. Effectiveness of the sexual attitude restructuring curriculum amongst Taiwanese graduate students. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.P.; Huang, Y.; Hsieh, C.M.; Zheng, Q.F. Knowledge of and attitude towards elderly sexuality and associated factors in Southern Taiwan. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2004, 16, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.F.; Lu, C.H.; Chen, I.J.; Yu, S. Sexual knowledge, attitudes and activity of older people in Taipei, Taiwan. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, B.Y. The Relationship between the Sexual Attitude and Job Satisfaction of Day Care Nurse Aides. Master’s Thesis, The Graduate School of Human Sexuality at Shu-Te University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hee, O.C. Validity and reliability of the customer-oriented behaviour scale in the health tourism hospitals in Malaysia. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 7, 771–775. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.P.; Huang, H.T. The concept and measurement of quality of life in elderly population. Taiwan Geriatr. Gerontol. 2014, 9, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Q. Quality of Sexual Life in Middle-Aged Patients with Primary Hypertension–In the Patients from the Armed Forces General Hospital in Taiwan. An Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, The Graduate School of Human Sexuality at Shu-Te University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, M.G.; Li, W.P.; Su, Z.Y.; Hsieh, C.M. The knowledge of and attitude towards elderly sexuality in Pingtung and the discussion on its relevant factors. Taiwan Geriatr. Gerontol. 2012, 7, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.W.; Wang, J.Z. Elderly sexuality knowledge and attitude in nursing students. J. Nurs. Healthc. Res. 2012, 8, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.W.; Wu, Z.X.; Tsai, W.H. Aging and sex life. Taiwan Geriatr. Gerontol. 2010, 5, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, L.; Bauer, M.; Fetherstonhaugh, D.; Chenco, C. Assessment of sexual health and sexual needs in residential aged care. Australas. J. Ageing 2015, 34, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Experimental Group (n = 31) | Control Group (n = 33) | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD, n (%) | M ± SD, n (%) | ||||

| Age | 54.90 ± 7.42 | 54.18 ± 7.63 | 0.383 | 0.703 | |

| Working hours | 264.38 ± 72.36 | 232.36 ± 59.45 | 1.94 | 0.57 | |

| Sex | Male | 6 (19.4%) | 7 (21.2%) | 0.34 | 0.854 |

| Female | 25 (80.6%) | 26 (78.8%) | |||

| Educational background | Primary school | 5 (16.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | 3.17 | 0.544 |

| Middle school | 11 (35.5%) | 9 (27.3%) | |||

| High school | 11 (35.5%) | 10 (30.3%) | |||

| University | 4 (12.9%) | 9 (27.3%) | |||

| Master’s | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.0%) | |||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 2 (6.5%) | 7 (21.2%) | 2.94 | 0.41 |

| Married | 14 (45.2%) | 13 (39.4%) | |||

| Divorced | 10 (32.3%) | 8 (24.2%) | |||

| Widowed | 5 (16.1%) | 5 (15.2%) | |||

| Fixed partner | None | 16 (94.1%) | 17 (85%) | 2.77 | 0.13 |

| Yes | 1 (5.9%%) | 3 (15%) | |||

| Religious beliefs | None | 2 (6.5%) | 9 (27.3%) | 0.87 | 0.27 |

| Yes | 29 (93.5%) | 24 (72.7%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Hokkien | 19 (61.3%) | 12 (36.4%) | 6.54 | 0.72 |

| Hakka | 0 | 3 (9.1%) | |||

| Aborigines | 0 | 1 (3.0%) | |||

| New immigrants | 12 (38.7%) | 16 (48.5%) | |||

| Migrant workers | 0 | 1 (3.0%) | |||

| Nationality | Chinese | 12 (100%) | 15 (94.4%) | 2.19 | 1 |

| Vietnamese | 0 | 1 (5.6) | |||

| Years of work experience | <1 year | 4 (12.9%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3.11 | 0.72 |

| 1–2 years | 2 (6.5%) | 3 (9.1%) | |||

| 2–3 years | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (9.1%) | |||

| 3–4 years | 4 (12.9%) | 5 (15.2%) | |||

| 4–5 years | 5 (16.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | |||

| >5 years | 13 (41.9%) | 18 (54.5%) | |||

| Sexual education | None | 24 (77.4%) | 23 (69.7%) | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| Yes | 7 (22.6%) | 10 (30.3%) | |||

| Heard of sexual harassment | None | 9 (29%) | 18 (54.5%) | 4.27 | 0.39 |

| Yes | 22 (71%) | 10 (45.5%) | |||

| Experienced sexual harassment | None | 19 (61.3%) | 19 (57.6%) | 0.91 | 0.76 |

| Yes | 12 (38.7%) | 14 (42.4%) | |||

| Type of sexual harassment | Verbal | 10 (32.3%) | 9 (27.3%) | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Physical | 5 (16.1%) | 9 (27.3%) | 1.16 | 0.28 | |

| Visual | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (3.0%) | 4.19 | 0.61 | |

| Source of sexual knowledge | School teachers | 13 (41.9%) | 15 (45.5%) | 0.8 | 0.78 |

| Friends/schoolmates | 18 (58.1%) | 8 (24.2%) | 7.58 | 0.06 | |

| TV | 14 (45.2%) | 9 (27.3%) | 2.22 | 0.14 | |

| Books and magazines | 13 (41.9%) | 10 (30.3%) | 0.94 | 0.33 | |

| Item | Experimental Group (n = 29) | Control Group (n = 29) | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | ||||

| Age | 77. 45 ± 8.45 | 78.86 ± 7.86 | −0.66 | 0.51 | |

| Sex | Male | 21 (72.4%) | 21 (72.4%) | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 8 (27.6%) | 8 (27.6%) | |||

| Educational background | Illiterate | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (10.3%) | 1.65 | 0.98 |

| Primary school | 15 (51.7%) | 13 (44.8%) | |||

| Middle school | 5 (17.2%) | 5 (17.2%) | |||

| High school | 4 (13.8%) | 5 (17.2%) | |||

| University | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||

| Master’s | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Religious beliefs | None | 6 (20.7%) | 5 (17.2%) | 6.35 | 0.25 |

| Buddhism | 12 (41.4%) | 10 (34.5%) | |||

| Taoism | 3 (10.3%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||

| General | 7 (24.1%) | 6 (20.7%) | |||

| Christianity | 0 (0%) | 5 (17.2%) | |||

| Others | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Hokkien | 18 (62.1%) | 21 (72.4%) | 0.96 | 0.87 |

| Hakka | 3 (10.3%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||

| Mainlanders | 6 (20.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | |||

| Others | 2 (6.9%) | 1 (3.4%) | |||

| Chronic disease | Yes | 29 (100%) | 29 (100%) | ||

| Taking medicines | Yes | 29 (100%) | 29 (100%) | ||

| Smoking | No | 16 (55.2%) | 20 (69.0%) | 1.89 | 0.64 |

| Yes | 4 (13.8%) | 3 (10.3%) | |||

| Given up | 9 (31.0%) | 6 (20.7%) | |||

| Drinking | No | 20 (69%) | 25 (86.2%) | 4.49 | 0.10 |

| Yes | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (6.9%) | |||

| Given up | 8 (27.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | |||

| Sexual behaviors | Yes | 13 (44.8%) | 7 (24.1%) | 2.75 | 0.10 |

| None | 16 (55.2%) | 22 (75.9%) | |||

| Method of sexual behaviors | Fantasizing | 13 (44.8%) | 7 (24.1%) | 2.75 | 0.10 |

| Touching | 9 (31%) | 4 (13.8%) | 2.48 | 0.12 | |

| Caressing | 8 (27.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | 1.68 | 0.20 | |

| Reason for asexuality | Social perspective | 9 (31%) | 10 (34.5%) | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| Disease | 7 (24.1%) | 9 (31%) | 0.35 | 0.56 | |

| Partner | 6 (20.7%) | 9 (31%) | 0.81 | 0.37 | |

| Relationship status | None | 63 (100%) | 29 (100%) | ||

| Wish to understand sexual education | No | 19 (65.5%) | 19 (65.5%) | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 10 (34.5%) | 10 (34.5%) | |||

| Variables | Pretest Mean ± SD | Posttest Mean ± SD | 4 WKS Post Mean ± SD | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| Experimental group | 21.35 ± 5.83 | 27.19 ± 3.06 | 28.10 ± 1.01 | 3.05 (−0.11–6.22) | 0.059 |

| Control group | 18.30 ± 7.25 | 17.97 ± 2.80 | 19.15 ± 5.14 | reference | |

| Time (Reference: Pretest) | |||||

| Posttest | −0.33 (−3.09–2.42) | 0.813 | |||

| 4 WKS Post | 0.85 (−1.91–3.61) | 0.547 | |||

| Group × Time (Reference: Control group × Pretest) | |||||

| Experimental group × Posttest | 6.17 (2.55–9.79) | 0.001 *** | |||

| Experimental group × 4 WKS Post | 5.89 (2.50–9.28) | 0.001 *** |

| Variables | Pretest Mean ± SD | Posttest Mean ± SD | 4 WKS Post Mean ± SD | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| Experimental group | 66.29 ± 7.68 | 74.42 ± 8.54 | 76.90 ± 7.62 | 3.38 (−0.76–7.53) | 0.110 |

| Control group | 62.91 ± 9.47 | 57.55 ± 3.89 | 59.88 ± 3.76 | reference | |

| Time (Reference: Pretest) | |||||

| Posttest | −5.36 (−8.99 to −1.73) | 0.004 * | |||

| 4 WKS post | −3.03 (−6.41–0.35) | 0.079 | |||

| Group × Time (Reference: Control group × Pretest) | |||||

| Experimental group × Posttest | 13.49 (7.92–19.06) | 0.000 * | |||

| Experimental group × 4 WKS Post | 13.64 (8.49–18.79) | 0.000 * |

| Variables | Pretest Mean ± SD | Posttest Mean ± SD | 4 WKS Post Mean ± SD | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| Experimental group | 34.97 ± 6.91 | 45.95 ± 3.09 | 45.71 ± 3.67 | −0.83 (−4.34–2.69) | 0.645 |

| Control group | 34.89 ± 6.32 | 35.52 ± 3.31 | 36.48 ± 2.94 | reference | |

| Time (Reference: Pretest) | |||||

| Posttest | 0.55 (−1.83–2.94) | 0.651 | |||

| 4 WKS Post | 1.51 (−1.17–4.21) | 0.270 | |||

| Group × Time (Reference: Control group × Pretest) | |||||

| Experimental group × Posttest | 11.48 (7.57–15.39) | 0.000 * | |||

| Experimental group × 4 WKS Post | 10.00 (5.942–14.06) | 0.000 * |

| Variables | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (Reference: Female) | 9.30 (6.49–12.13) | 0.000 *** |

| Group (Reference: Control group) | ||

| Experimental group | −0.83 (−3.33 to −1.67) | 0.52 |

| Time (Reference: Pretest) | ||

| Posttest | 6.39 (2.52–10.25) | 0.001 ** |

| 4 WKS Post | 8.06 (5.33–10.79) | 0.000 *** |

| Group × Time (Reference: Control group × Pretest) | ||

| Experimental group × Posttest | 11.48 (8.03–14.93) | 0.000 *** |

| Experimental group × 4 WKS Post | 10.00 (6.52–13.48) | 0.000 *** |

| Sex × group (Male × Experimental group) | −1.00 (−1.86–1.86) | 1.00 |

| Sex × Time (Reference: Female × Pretest) | ||

| Male × Posttest | −8.05 (−11.81 to −4.30) | 0.000 *** |

| Male × 4 WKS Post | −9.03 (−12.46 to −5.62) | 0.000 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.-H.; Yang, S.-T.; Wang, T.-F.; Chang, L.-C. Effectiveness of a Sexuality Workshop for Nurse Aides in Long-Term Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312372

Yang M-H, Yang S-T, Wang T-F, Chang L-C. Effectiveness of a Sexuality Workshop for Nurse Aides in Long-Term Care Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312372

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Man-Hua, Shu-Ting Yang, Tze-Fang Wang, and Li-Chun Chang. 2021. "Effectiveness of a Sexuality Workshop for Nurse Aides in Long-Term Care Facilities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312372

APA StyleYang, M.-H., Yang, S.-T., Wang, T.-F., & Chang, L.-C. (2021). Effectiveness of a Sexuality Workshop for Nurse Aides in Long-Term Care Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312372