Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence Risk, Cancer Staging, and Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer under Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Study Samples

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on the Incidence Risk of Colorectal Cancer

3.3. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on the Stage of Colorectal Cancer at Diagnosis

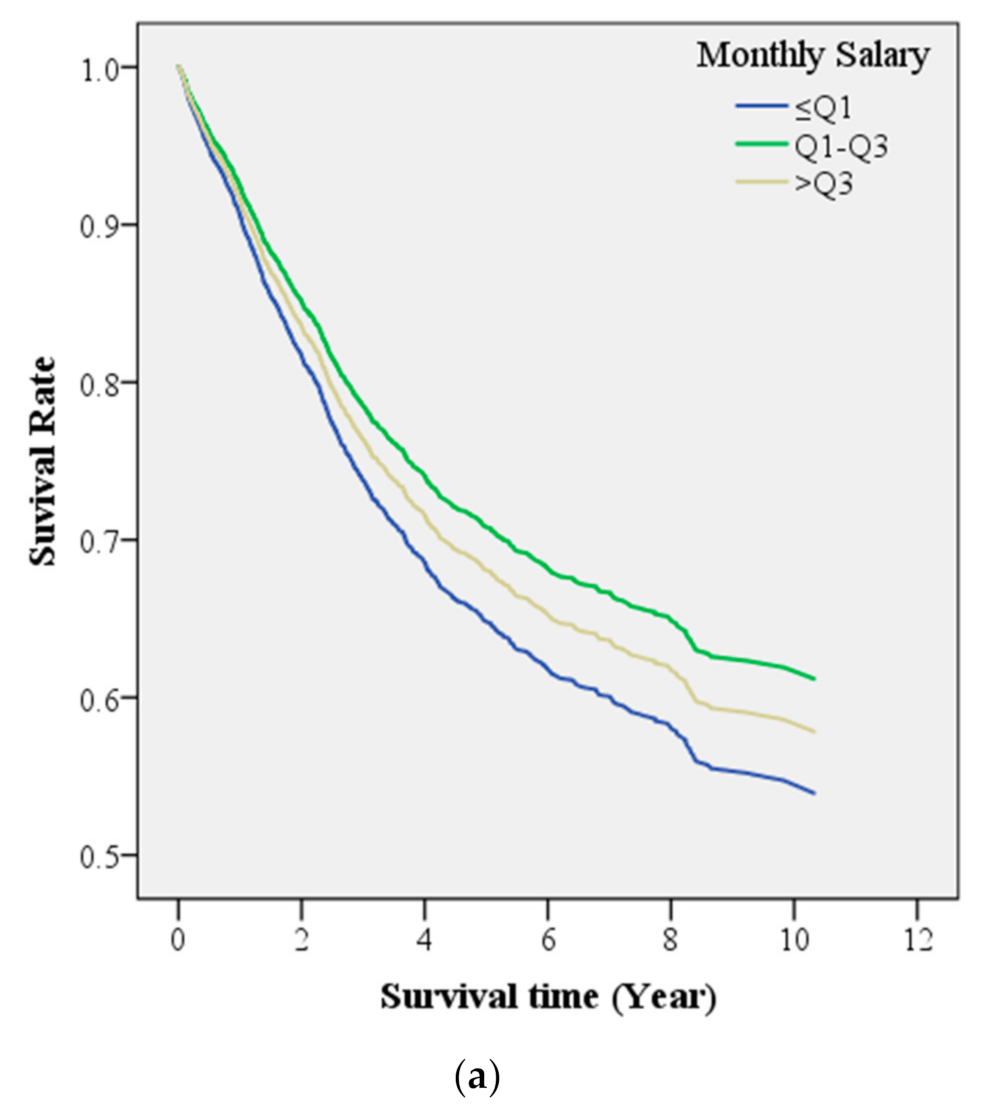

3.4. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on the Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taiwan Health Promotion Administration. Taiwan Cancer Registry Cancer Incidence. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1061&pid=6069 (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare and Statistics Department. 2017 Cause of Death Statistics. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/lp-3961-2.html (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Kaplan, G.A. Part III summary: What is the role of the social environment in understanding inequalities in health? In Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social, Psychological, and Biological Pathways; Adler, N.E., Marmot, M., McEwen, B., Stewart, J., Eds.; New York Academy of Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 896, pp. 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.M.; Su, Y.C.; Lai, N.S.; Huang, K.Y.; Chien, S.H.; Chang, Y.H.; Lian, W.C.; Hsu, T.W.; Lee, C.C. The Combined Effect of Individual and Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Survival Rates. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44325. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.C.; Lee, C.H.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Huang, H.L.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.; Shih, S.F.; Shin, S.J.; Tsai, W.C.; Chen, T.; et al. Poverty Increases Type 2 Diabetes Incidence and Inequality of Care Despite Universal Health Coverage. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.W.; Ho, C.H.; Wang, J.J.; Hsieh, K.Y.; Weng, S.F.; Wu, M.P. Longitudinal Trends of the Healthcare-Seeking Prevalence and Incidence of Insomnia in Taiwan: An 8-year Nationally Representative Study. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastert, T.A.; Beresford, S.A.; Sheppard, L.; White, E. Disparities in Cancer Incidence and Mortality by Area-Level Socioeconomic Status: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, K.A.; Sherman, R.L.; McDonald, K.; Johnson, C.J.; Lin, G.; Stroup, A.M.; Boscoe, F.P. Associations of Census-Tract Poverty with Subsite-Specific Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates and Stage of Disease at Diagnosis in the United States. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014, 2014, 823484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladabaum, U.; Clarke, C.A.; Press, D.J.; Mannalithara, A.; Myer, P.A.; Cheng, I.; Gomez, S.L. Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Asian Populations in California: Effect of Nativity and Neighborhood-Level Factors. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuldiner, J.; Liu, Y.; Lofters, A. Incidence of Breast and Colorectal Cancer Among Immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A Retrospective Cohort Study from 2004–2014. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrecher, A.; Fish, K.; Clarke, C.A.; West, D.W.; Gomez, S.L.; Cheng, I. Examining the Association Between Socioeconomic Status and Invasive Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality in California. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, A.; Schmidlin, K.; Bordoni, A.; Bouchardy, C.; Bulliard, J.L.; Camey, B.; Konzelmann, I.; Maspoli, M.; Wanner, M.; Zwahlen, M.; et al. Socioeconomic and Demographic Inequalities in Stage at Diagnosis and Survival among Colorectal Cancer Patients: Evidence from a Swiss Population-Based Study. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M.T.; Pavluck, A.L.; Ko, C.Y.; Ward, E.M. Factors Associated with Colon Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 2680–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, K.M.; Peck, J.D.; Vesely, S.K.; Janitz, A.E.; Snider, C.A.; Dougherty, T.M.; Campbell, J.E. Effect Modification of the Association Between Race and Stage at Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis by Socioeconomic Status. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25, S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Tahseen, A.; England, E.; Wolfe, K.; Simhachalam, M.; Homan, T.; Sitenga, J.; Walters, R.W.; Silberstein, P.T. Association between Primary Payer Status and Survival in Patients with Stage III Colon Cancer: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2019, 18, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, E.; Attwood, K.; Al-Sukhni, E.; Erwin, D.; Boland, P.; Nurkin, S. Age-Related Rates of Colorectal Cancer and the Factors Associated with Overall Survival. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 9, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastert, T.A.; Ruterbusch, J.J.; Beresford, S.A.; Sheppard, L.; White, E. Contribution of Health Behaviors to the Association Between Area-Level Socioeconomic Status and Cancer Mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982 2016, 148, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, R.; Markossian, T.; Johnson, A.; Dong, F.; Bayakly, R. Geographic Residency Status and Census Tract Socioeconomic Status as Determinants of Colorectal Cancer Outcomes. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, E63–E71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.; Kim, C. Disparities by Age, Sex, Tumor Stage, Diagnosis Path, and Area-level Socioeconomic Status in Survival Time for Major Cancers: Results from the Busan Cancer Registry. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, D.; Cai, S.; Li, Q.; Li, X. Real-World Implications of Nonbiological Factors with Staging, Prognosis and Clinical Management in Colon Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pule, M.L.; Buckley, E.; Niyonsenga, T.; Roder, D. The Effects of Comorbidity on Colorectal Cancer Mortality in an Australian Cancer Population. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöström, O.; Silander, G.; Syk, I.; Henriksson, R.; Melin, B.; Hellquist, B.N. Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Between Northern and Southern Sweden—A Report from the New RISK North database. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skyrud, K.D.; Bray, F.; Eriksen, M.T.; Nilssen, Y.; Møller, B. Regional Variations in Cancer Survival: Impact of Tumour Stage, Socioeconomic Status, Comorbidity and Type of Treatment in Norway. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Huang, R.; Xie, L.; Liu, E.; Chen, Y.G.; Wang, G.; Wang, X. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Survival of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 106121–106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, H.L.; Talbäck, M.; Martling, A.; Feychting, M.; Ljung, R. Socioeconomic Position and Incidence of Colorectal Cancer in the Swedish Population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 40, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Nugent, Z.; Decker, K.; Demers, A.; Samadder, J.; Torabi, M. Geographic Variation and Factors Associated with Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Manitoba. Can. J. Public Health 2018, 108, e558–e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Booth, C.M.; Li, G.; Zhang-Salomons, J.; Mackillop, W.J. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Stage of Cancer at Diagnosis and Survival A Population-Based Study in Ontario, Canada. Cancer 2010, 116, 4160–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, K.R.; Bennett, A.; Young, G.P.; Cole, S.R.; Joshi, R.; Adams, J.; Singhal, N.; Karapetis, C.; Wattchow, D.; Roder, D. Sociodemographic Disparities in Survival from Colorectal Cancer in South Australia: A Population-Wide Data Linkage Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Executive Yuan, R.O.C. Important Gender Statistics Database—Actual Coverage Rate of National Health Insurance. Available online: https://www.gender.ey.gov.tw/gecdb/Stat_Statistics_Query.aspx?sn=OU8Vo8ydhvbx1qKbUarVHw%3d%3d&statsn=u4ceyDJ9iGzBYUGlJC0z7w%3d%3d (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Tervonen, H.E.; Aranda, S.; Roder, D.; You, H.; Walton, R.; Morrell, S.; Baker, D.; Currow, D.C. Cancer Survival Disparities Worsening by Socio-economic Disadvantage over the Last 3 Decades in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dik, V.K.; Aarts, M.J.; Van Grevenstein, W.M.U.; Koopman, M.; Van Oijen, M.G.H.; Lemmens, V.E.; Siersema, P.D. Association Between Socioeconomic Status, Surgical Treatment and Mortality in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC). The 2000 and 2005 Longitudinal Generation Tracking Database (LGTD 2000, LGTD 2005) Establishment and Verification Report for 2 Million Sampled People. 2020. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-2506-3633-113.html (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Maajani, K.; Jalali, A.; Alipour, S.; Khodadost, M.; Tohidinik, H.R.; Yazdani, K. The global and regional survival rate of women with breast Cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyo, R.A.; Cherkin, D.C.; Ciol, M.A. Adapting a Clinical Comorbidity Index for Use with ICD-9-CM Administrative Databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Hung, Y.T.; Chuang, Y.L.; Chen, Y.J.; Weng, W.S.; Liu, J.S.; Liang, K.J.J.H.M. Incorporating Development Stratification of Taiwan Townships into Sampling Design of Large Scale Health Interview Survey. J. Health Manag. 2006, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.N. SAS. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kaplan-Meier, M.K. Survival Curves and the Log-Rank Test, in Survival Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 55–96. [Google Scholar]

- Savijärvi, S.; Seppä, K.; Malila, N.; Pitkäniemi, J.; Heikkinen, S. Trends of Colorectal Cancer Incidence by Education and Socioeconomic Status in Finland. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Du, X.L. Risks of Developing Breast and Colorectal Cancer in Association with Incomes and Geographic Locations in Texas: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Atinmo, T.; Byers, T.; Chen, J.; Hirohata, T.; Jackson, A.; James, W.; Kolonel, L.; Kumanyika, S.; Leitzmann, C. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. 2007. Available online: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/4841/1/4841.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1077&pid=6201 (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Doubeni, C.A.; Laiyemo, A.O.; Major, J.M.; Schootman, M.; Lian, M.; Park, Y.; Graubard, B.I.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Sinha, R. Socioeconomic Status and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: An Analysis of More Than a Half Million Adults in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer 2012, 118, 3636–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyratzopoulos, G.; Abel, G.A.; Brown, C.H.; Rous, B.A.; Vernon, S.A.; Roland, M.; Greenberg, D.C. Socio-demographic Inequalities in Stage of Cancer Diagnosis: Evidence from Patients with Female Breast, Lung, Colon, Rectal, Prostate, Renal, Bladder, Melanoma, Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, O. Outcomes of Non-Metastatic Colon Cancer Patients in Relationship to Socioeconomic Status: An Analysis of SEER Census Tract-Level Socioeconomic Database. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 24, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Yen, A.M.; Chiu, S.Y.; Fann, J.C.; Chuang, S.L.; Hsu, W.F.; Chiang, T.H.; Chiu, H.M.; et al. Effects of Screening and Universal Healthcare on Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.; Donaleshen, J.; Helewa, R.M.; Park, J.; Wirtzfeld, D.; Hochman, D.; Singh, H.; Turner, D. Does Young Age Influence the Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, M.; Green, C.; Nugent, Z.; Mahmud, S.; Demers, A.; Griffith, J.; Singh, H. Geographical Variation and Factors Associated with Colorectal Cancer Mortality in a Universal Health Care System. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 28, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.Y.; Huang, J.Y. Effect of Nationwide Screening Program on Colorectal Cancer Mortality in Taiwan: A Controlled Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2020, 35, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli-Bjorkman, N.; Lambe, M.; Eaker, S.; Sandin, F.; Glimelius, B. Differences According to Educational Level in the Management and Survival of Colorectal Cancer in Sweden. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.; Ziogas, A.; Lipkin, S.M.; Zell, J.A. Effects of Socioeconomic Status and Treatment Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008, 17, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total | Monthly Salary | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤Q1 | Q1–Q3 | >Q3 | p-Value a | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 286,792 | 100 | 97,884 | 34.13 | 99,356 | 34.64 | 89,552 | 31.23 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 101,469 | 35.38 | 43,081 | 42.46 | 17,406 | 17.15 | 40,982 | 40.39 | |

| Junior high school | 53,372 | 18.61 | 18,465 | 34.60 | 9150 | 17.14 | 25,757 | 48.26 | |

| Senior high/vocational school | 100,012 | 34.87 | 27,963 | 27.96 | 41,424 | 41.42 | 30,625 | 30.62 | |

| Junior college/university and above | 31,939 | 11.14 | 8375 | 26.22 | 1992 | 6.24 | 21,572 | 67.54 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 152,943 | 53.33 | 53,033 | 34.68 | 44,496 | 29.09 | 55,414 | 36.23 | |

| Female | 133,849 | 46.67 | 44,851 | 33.51 | 54,860 | 40.99 | 34,138 | 25.50 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 40–54 | 167,744 | 58.49 | 34,659 | 20.66 | 69,212 | 41.26 | 63,873 | 38.08 | |

| 55–64 | 47,864 | 16.69 | 19,778 | 41.32 | 17,066 | 35.66 | 11,020 | 23.02 | |

| 65–74 | 39,060 | 13.62 | 20,744 | 53.11 | 9077 | 23.24 | 9239 | 23.65 | |

| ≥75 | 32,124 | 11.20 | 22,703 | 70.67 | 4001 | 12.45 | 5420 | 16.87 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single | 25,407 | 8.86 | 14,515 | 57.13 | 5501 | 21.65 | 5391 | 21.22 | |

| Married | 221,416 | 77.20 | 62,696 | 28.32 | 82,369 | 37.20 | 76,351 | 34.48 | |

| Divorced or widowed | 39,969 | 13.94 | 20,673 | 51.72 | 11,486 | 28.74 | 7810 | 19.54 | |

| CCI score | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 169,420 | 59.07 | 49,755 | 29.37 | 62,963 | 37.16 | 56,702 | 33.47 | |

| 1 | 61,300 | 21.37 | 21,524 | 35.11 | 20,571 | 33.56 | 19,205 | 31.33 | |

| 2 | 27,091 | 9.45 | 11,720 | 43.26 | 8221 | 30.35 | 7150 | 26.39 | |

| ≥3 | 28,981 | 10.10 | 14,885 | 51.36 | 7601 | 26.23 | 6495 | 22.41 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Level 1 | 96,738 | 33.73 | 28,793 | 29.76 | 32,134 | 33.22 | 35,811 | 37.02 | |

| Level 2 | 104,458 | 36.42 | 33,617 | 32.18 | 42,852 | 41.02 | 27,989 | 26.79 | |

| Level 3 | 44,623 | 15.56 | 16,917 | 37.91 | 12,449 | 27.90 | 15,257 | 34.19 | |

| Level 4 | 29,523 | 10.29 | 11,345 | 38.43 | 10,249 | 34.72 | 7929 | 26.86 | |

| Levels 5–7 | 11,450 | 3.99 | 7212 | 62.99 | 1672 | 14.60 | 2566 | 22.41 | |

| Variables | With Cancer | Without Cancer | p-Value a | aHR b | 95% CI | p-Value c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||||

| Total | 5500 | 1.92 | 281,292 | 98.08 | |||||

| Monthly salary | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤Q1 | 2030 | 2.07 | 95,854 | 97.93 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.85 | <0.001 | |

| Q1–Q3 | 1890 | 1.90 | 97,466 | 98.10 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.19 | 0.005 | |

| >Q3 | 1580 | 1.76 | 87,972 | 98.24 | 1.00 | ||||

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 2498 | 2.46 | 98,971 | 97.54 | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.31 | 0.002 | |

| Junior high school | 916 | 1.72 | 52,456 | 98.28 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.28 | 0.020 | |

| Senior high/vocational school | 1584 | 1.58 | 98,428 | 98.42 | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.21 | 0.076 | |

| Junior college/university and above | 502 | 1.57 | 31,437 | 98.43 | 1.00 | ||||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 3284 | 2.15 | 149,659 | 97.85 | 1.46 | 1.38 | 1.55 | <0.001 | |

| Female | 2216 | 1.66 | 131,633 | 98.34 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 40–54 | 1896 | 1.13 | 165,848 | 98.87 | 1.00 | ||||

| 55–64 | 1280 | 2.67 | 46,584 | 97.33 | 2.56 | 2.37 | 2.77 | <0.001 | |

| 65–74 | 1335 | 3.42 | 37,725 | 96.58 | 3.62 | 3.33 | 3.93 | <0.001 | |

| ≥75 | 989 | 3.08 | 31,135 | 96.92 | 4.42 | 4.03 | 4.86 | <0.001 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single | 342 | 1.35 | 25,065 | 98.65 | 1.00 | ||||

| Married | 4294 | 1.94 | 217,122 | 98.06 | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.23 | 0.084 | |

| Divorced or widowed | 864 | 2.16 | 39,105 | 97.84 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.31 | 0.032 | |

| CCI score | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 2791 | 1.65 | 166,629 | 98.35 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1 | 1305 | 2.13 | 59,995 | 97.87 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 0.169 | |

| 2 | 670 | 2.47 | 26,421 | 97.53 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 0.048 | |

| ≥3 | 734 | 2.53 | 28,247 | 97.47 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.24 | 0.003 | |

| Urbanization level | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Level 1 | 1933 | 2.00 | 94,805 | 98.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Level 2 | 2071 | 1.98 | 102,387 | 98.02 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.339 | |

| Level 3 | 799 | 1.79 | 43,824 | 98.21 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.032 | |

| Level 4 | 525 | 1.78 | 28,998 | 98.22 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 1.01 | 0.085 | |

| Levels 5–7 | 172 | 1.50 | 11,278 | 98.50 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 0.009 | |

| Variables | Age 40–54 | Age 55–64 | Age ≥ 65 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | ||||

| Monthly salary | ||||||||||||

| ≤Q1 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Q1–Q3 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.14 | 0.092 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 0.265 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 0.799 |

| >Q3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 1.24 | 1.11 | 1.37 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.53 | 0.051 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.06 | 0.177 |

| Junior high school | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.33 | 0.002 | 1.35 | 1.06 | 1.72 | 0.014 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 1.22 | 0.981 |

| Senior high/vocational school | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.24 | 0.025 | 1.29 | 1.04 | 1.59 | 0.022 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 1.22 | 0.869 |

| Junior college/university and above | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Variables | Early Stage a | Late Stage b | p-Value c | aOR d | 95% CI | p-Value e | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||||

| Total (n = 3630) | 1576 | 43.42 | 2054 | 56.58 | |||||

| Monthly salary | 0.510 | ||||||||

| ≤Q1 | 591 | 43.52 | 767 | 56.48 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 1.20 | 0.930 | |

| Q1–Q3 | 534 | 42.28 | 729 | 57.72 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 1.26 | 0.565 | |

| >Q3 | 451 | 44.70 | 558 | 55.30 | 1.00 | ||||

| Education | 0.265 | ||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 717 | 43.19 | 943 | 56.81 | 1.14 | 0.88 | 1.48 | 0.314 | |

| Junior high school | 242 | 40.81 | 351 | 59.19 | 1.24 | 0.94 | 1.65 | 0.133 | |

| Senior high/vocational school | 466 | 44.00 | 593 | 56.00 | 1.10 | 0.86 | 1.43 | 0.445 | |

| Junior college/university and above | 151 | 47.48 | 167 | 52.52 | 1.00 | ||||

| Gender | 0.164 | ||||||||

| Male | 956 | 44.36 | 1199 | 55.64 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 1.11 | 0.569 | |

| Female | 620 | 42.03 | 855 | 57.97 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age | 0.867 | ||||||||

| 40–54 | 310 | 42.41 | 421 | 57.59 | 1.00 | ||||

| 55–64 | 417 | 42.99 | 553 | 57.01 | 1.01 | 0.83 | 1.24 | 0.909 | |

| 65–74 | 373 | 43.68 | 481 | 56.32 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 0.985 | |

| ≥75 | 476 | 44.28 | 599 | 55.72 | 0.97 | 0.77 | 1.21 | 0.763 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single | 81 | 35.68 | 146 | 64.32 | 1.00 | ||||

| Married | 1282 | 45.03 | 1565 | 54.97 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.009 | |

| Divorced or widowed | 213 | 38.31 | 343 | 61.69 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.26 | 0.556 | |

| CCI score | 0.069 | ||||||||

| 0 | 791 | 41.39 | 1120 | 58.61 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1 | 380 | 45.62 | 453 | 54.38 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.040 | |

| 2 | 200 | 46.73 | 228 | 53.27 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.042 | |

| ≥3 | 205 | 44.76 | 253 | 55.24 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 1.09 | 0.236 | |

| Urbanization level | 0.866 | ||||||||

| Level 1 | 563 | 43.24 | 739 | 56.76 | 1.00 | ||||

| Level 2 | 586 | 43.63 | 757 | 56.37 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 1.15 | 0.836 | |

| Level 3 | 237 | 44.38 | 297 | 55.62 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 1.18 | 0.675 | |

| Level 4 | 143 | 43.33 | 187 | 56.67 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 1.26 | 0.929 | |

| Levels 5–7 | 47 | 38.84 | 74 | 61.16 | 1.25 | 0.85 | 1.84 | 0.259 | |

| Variables | All | ≤Q1 | Q1–Q3 | >Q3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR c | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR c | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR c | 95% CI | p-Value b | |||||

| Monthly salary | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤Q1 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.33 | 0.096 | ||||||||||||

| Q1–Q3 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 1.03 | 0.099 | ||||||||||||

| >Q3 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 1.39 | 1.09 | 1.77 | 0.009 | 1.16 | 0.81 | 1.66 | 0.412 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 1.96 | 0.938 | 1.96 | 1.28 | 2.98 | 0.002 |

| Junior high school | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.47 | 0.364 | 1.08 | 0.73 | 1.61 | 0.691 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 1.84 | 0.755 | 1.15 | 0.68 | 1.93 | 0.602 |

| Senior high/vocational school | 1.11 | 0.87 | 1.41 | 0.405 | 1.02 | 0.71 | 1.47 | 0.922 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 1.73 | 0.653 | 1.14 | 0.78 | 1.68 | 0.495 |

| Junior college/university and above | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.38 | 0.002 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 1.42 | 0.197 | 1.41 | 1.14 | 1.75 | 0.001 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.37 | 0.644 |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 40–54 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 55–64 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 1.01 | 0.058 | 1.05 | 0.71 | 1.56 | 0.805 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.96 | 0.027 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 1.31 | 0.684 |

| 65–74 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 1.29 | 0.566 | 1.11 | 0.76 | 1.63 | 0.582 | 1.29 | 0.93 | 1.77 | 0.124 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 1.41 | 0.869 |

| ≥75 | 1.47 | 1.20 | 1.78 | <0.001 | 1.67 | 1.16 | 2.40 | 0.006 | 1.34 | 0.92 | 1.95 | 0.130 | 1.53 | 1.03 | 2.27 | 0.034 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Married | 0.97 | 0.76 | 1.24 | 0.824 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 1.37 | 0.943 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 1.26 | 0.302 | 0.75 | 0.36 | 1.57 | 0.446 |

| Divorced or widowed | 1.06 | 0.80 | 1.39 | 0.692 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.65 | 0.460 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 1.28 | 0.271 | 0.71 | 0.32 | 1.60 | 0.413 |

| CCI score | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.09 | 0.391 | 1.17 | 0.92 | 1.48 | 0.192 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.36 | 0.778 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 1.09 | 0.90 | 1.31 | 0.393 | 1.21 | 0.91 | 1.60 | 0.194 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 1.29 | 0.508 | 1.04 | 0.71 | 1.52 | 0.838 |

| ≥3 | 1.26 | 1.05 | 1.50 | 0.013 | 1.38 | 1.06 | 1.80 | 0.018 | 1.06 | 0.74 | 1.53 | 0.737 | 1.40 | 0.97 | 2.01 | 0.070 |

| Urbanization level | ||||||||||||||||

| Level 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Level 2 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.17 | 0.755 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0.081 | 1.22 | 0.96 | 1.55 | 0.102 | 1.19 | 0.90 | 1.56 | 0.224 |

| Level 3 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 0.932 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 1.31 | 0.917 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 1.34 | 0.731 | 1.27 | 0.89 | 1.81 | 0.190 |

| Level 4 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.32 | 0.600 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 1.30 | 0.679 | 1.02 | 0.68 | 1.53 | 0.930 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 2.36 | 0.052 |

| Levels 5–7 | 1.28 | 0.93 | 1.75 | 0.124 | 1.39 | 0.92 | 2.09 | 0.121 | 0.84 | 0.39 | 1.78 | 0.644 | 1.37 | 0.65 | 2.86 | 0.408 |

| Cancer stage | ||||||||||||||||

| Stage I | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Stage II | 2.23 | 1.58 | 3.13 | <0.001 | 1.83 | 1.16 | 2.90 | <0.001 | 3.68 | 1.65 | 8.22 | 0.001 | 1.97 | 0.98 | 3.98 | 0.058 |

| Stage III | 5.07 | 3.62 | 7.08 | <0.001 | 3.92 | 2.50 | 6.14 | <0.001 | 8.60 | 3.87 | 19.11 | <0.001 | 5.68 | 2.87 | 11.22 | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 25.82 | 18.46 | 36.10 | <0.001 | 21.09 | 13.35 | 33.31 | <0.001 | 42.51 | 19.11 | 94.55 | <0.001 | 32.90 | 16.69 | 64.84 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||||||||||||||||

| Surgery | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 1.29 | 1.01 | 1.65 | 0.045 | 1.06 | 0.74 | 1.53 | 0.740 | 2.07 | 1.28 | 3.36 | 0.003 | 1.18 | 0.70 | 2.01 | 0.535 |

| Radiotherapy | 3.22 | 1.93 | 5.37 | <0.001 | 3.43 | 1.82 | 6.46 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 0.30 | 5.61 | 0.730 | 16.55 | 4.77 | 57.46 | <0.001 |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.021 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.003 | 0.90 | 0.59 | 1.36 | 0.608 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 1.30 | 0.440 |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 1.78 | 1.16 | 2.72 | 0.008 | 2.13 | 1.25 | 3.61 | 0.005 | 2.69 | 1.04 | 6.92 | 0.040 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 1.99 | 0.447 |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 1.46 | 1.10 | 1.95 | 0.009 | 0.87 | 0.55 | 1.36 | 0.538 | 2.35 | 1.36 | 4.04 | 0.002 | 1.75 | 0.98 | 3.12 | 0.060 |

| Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy | 1.07 | 0.86 | 1.33 | 0.530 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 1.09 | 0.155 | 1.48 | 0.97 | 2.28 | 0.071 | 1.14 | 0.73 | 1.78 | 0.560 |

| Hospital ownership | ||||||||||||||||

| Public | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Private | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 0.783 | 1.07 | 0.88 | 1.29 | 0.499 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 1.03 | 0.084 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 0.449 |

| Hospital level | ||||||||||||||||

| Medical center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Regional hospital | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 0.014 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 1.55 | 0.019 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 1.09 | 0.247 | 1.23 | 0.68 | 2.25 | 0.495 |

| District hospital | 1.08 | 0.79 | 1.48 | 0.621 | 1.10 | 0.71 | 1.70 | 0.685 | 1.12 | 0.56 | 2.22 | 0.749 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 1.74 | 0.007 |

| Variables | Age 40–54 | Age 55–64 | Age ≥65 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | aHR a | 95% CI | p-Value b | ||||

| Monthly salary | ||||||||||||

| ≤Q1 | 1.16 | 0.75 | 1.80 | 0.511 | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.54 | 0.649 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.39 | 0.177 |

| Q1–Q3 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 1.41 | 0.955 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.050 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 1.10 | 0.262 |

| >Q3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school and under | 1.85 | 1.02 | 3.37 | 0.044 | 1.72 | 1.05 | 2.81 | 0.031 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 1.83 | 0.151 |

| Junior high school | 2.06 | 1.19 | 3.56 | 0.010 | 1.30 | 0.76 | 2.23 | 0.346 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 1.46 | 0.917 |

| Senior high/vocational school | 1.52 | 0.94 | 2.46 | 0.088 | 1.25 | 0.78 | 2.00 | 0.363 | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.49 | 0.876 |

| Junior college/university and above | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, W.-Y.; Hsu, H.-S.; Kung, P.-T.; Tsai, W.-C. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence Risk, Cancer Staging, and Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer under Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212164

Kuo W-Y, Hsu H-S, Kung P-T, Tsai W-C. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence Risk, Cancer Staging, and Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer under Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212164

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Wei-Yin, Han-Sheng Hsu, Pei-Tseng Kung, and Wen-Chen Tsai. 2021. "Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence Risk, Cancer Staging, and Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer under Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Taiwan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212164

APA StyleKuo, W.-Y., Hsu, H.-S., Kung, P.-T., & Tsai, W.-C. (2021). Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence Risk, Cancer Staging, and Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer under Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212164