Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction among Supplementary Grandparent Caregivers in Urban China: Mediated by Social Support and Moderated by Hukou Status

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction

1.2. Informal and Formal Social Support as Mediators

1.3. Hukou Status as a Moderator

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Domestic Generative Acts

2.2.2. Social Support

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.2.4. Hukou Status

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

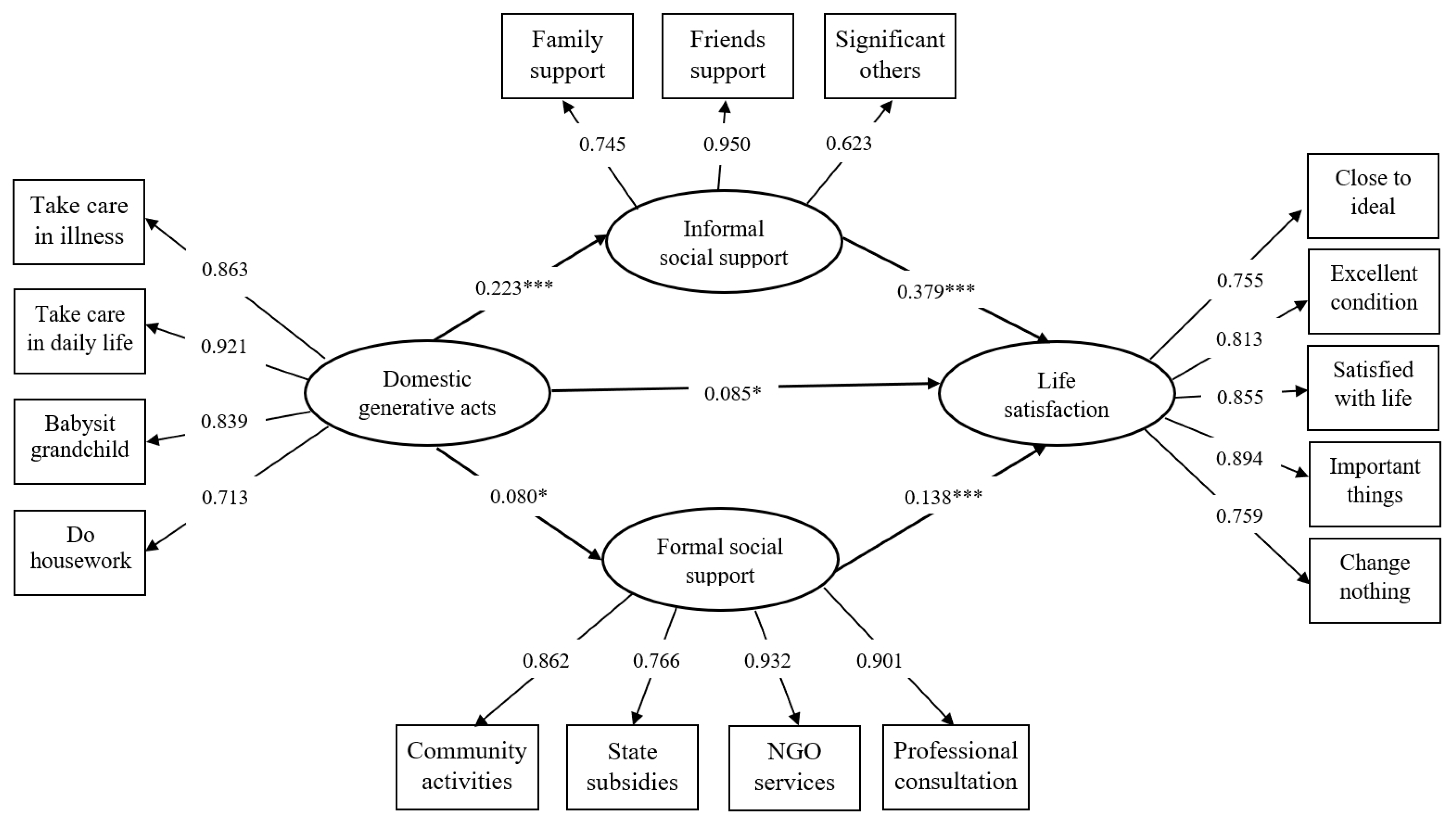

3.2. Testing for the Mediation Effect

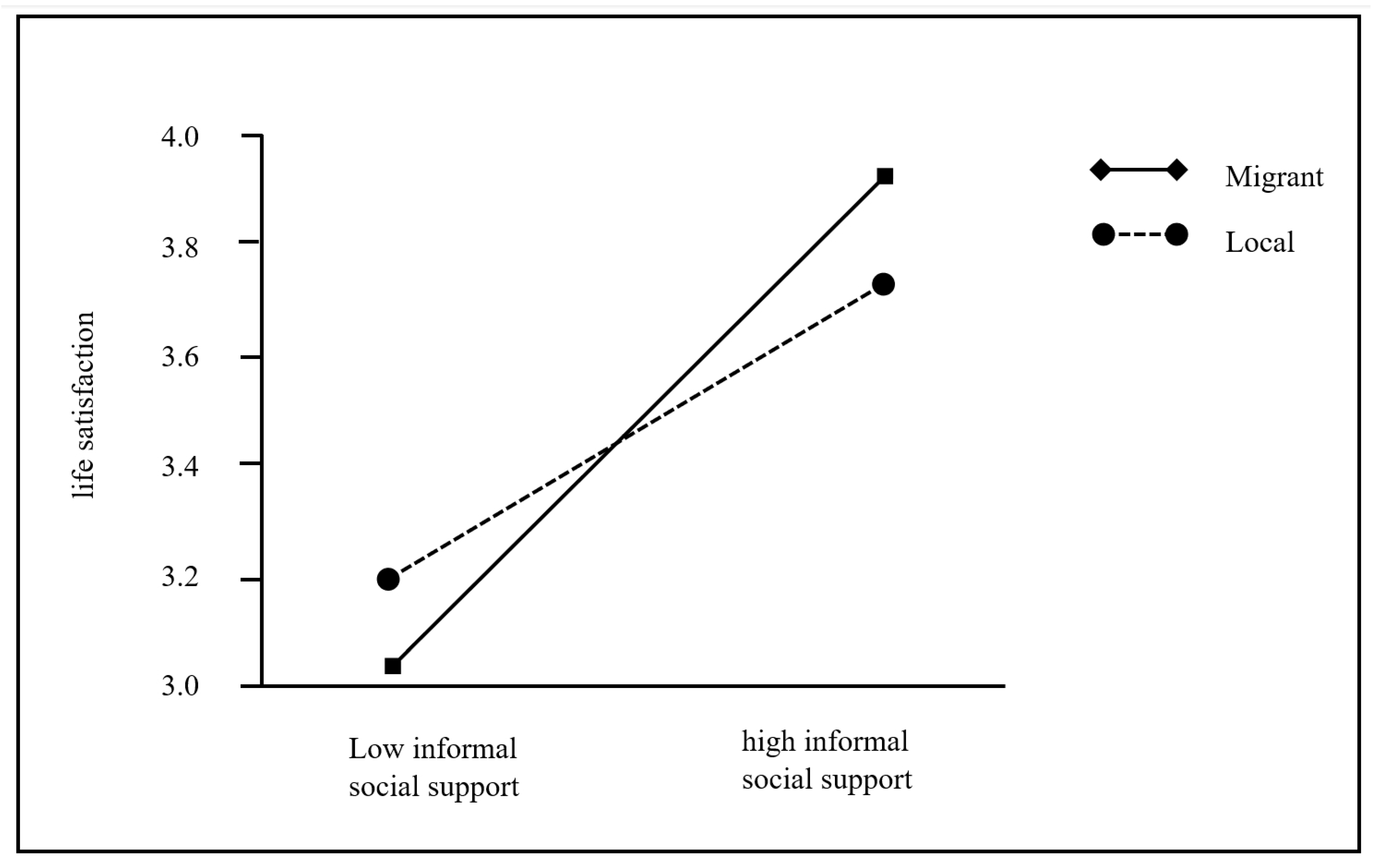

3.3. Testing for Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arber, S.; Timonen, V. A new look at grandparenting. In Contemporary Grandparenting: Changing Family Relationships in Global Contexts; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gessa, G.; Glaser, K.; Tinker, A. The health impact of intensive and nonintensive grandchild care in Europe: New evidence from SHARE. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Benefits of grandparental caregiving in Chinese older adults: Reduced lonely dissatisfaction as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.A.; Silverstein, M. The well-being of grandparents caring for grandchildren in rural China and the United States. In Contemporary Grandparenting: Changing Family Relationships in Global Contexts; Arber, S., Timonen, V., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kang, H.; Johnson-Motoyama, M. The psychological well-being of grandparents who provide supplementary grandchild care: A systematic review. J. Fam. Stud. 2017, 23, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chi, I. Determinants of support exchange between grandparents and grandchildren in rural China: The roles of grandparent caregiving, patrilineal heritage, and emotional bonds. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.D.; Hayslip, B., Jr.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, W. Grandparents as the primary care providers for their grandchildren: A cross-cultural comparison of Chinese and US Samples. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2019, 89, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Zuo, D. Grandparents caring for grandchildren in rural China: Consequences for emotional and cognitive health in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 2042–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.W. Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Bringing children to the cities: Gendered migrant parenting and the family dynamics of rural-urban migrants in China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 1460–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rose, N. Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants: A review and call for research. Health Place 2017, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; Ma, S.; Jiang, M.; Li, L. The effect of migration on social capital and depression among older adults in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayslip, B.; Blumenthal, H.; Garner, A. Social support and grandparent caregiver health: One-year longitudinal findings for grandparents raising their grandchildren. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, J.M.; Landry-Meyer, L.; Roe, J.G. Grandparents raising grandchildren: The role of social support in coping with caregiving challenges. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2006, 62, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Huang, J. Impacts of intergenerational care for grandchildren and intergenerational support on the psychological well-being of the elderly in China. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 2020, 29, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Emery, T.; Dykstra, P. Grandparenthood in China and Western Europe: An analysis of CHARLS and SHARE. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 45, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F.; Celdrán, M.; Triado, C. Grandmothers offering regular auxiliary care for their grandchildren: An expression of generativity in later life? J. Women Aging 2012, 24, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society, 2nd ed.; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlman, K.; Ligon, M. The application of a generativity model for older adults. Intern. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2012, 74, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chee, K.H.; Gerhart, O. Redefining generativity: Through life course and pragmatist lenses. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, E.D.S.; McAdams, D.P. The relations of generative concern and generative action to personality traits, satisfaction/happiness with life, and ego development. J. Adult Dev. 1995, 2, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; de St Aubin, E. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarey, J. Reflections on generativity and flourishing: A response to Snow’s Kohlberg Memorial Lecture. J. Moral Educ. 2015, 44, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, H.; Ngai, S.S.-y. Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Dong, X.-y.; Zhang, Y. Grandparent-provided childcare and labor force participation of mothers with preschool children in urban China. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 2019, 2, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoklitsch, A.; Baumann, U. Generativity and aging: A promising future research topic? J. Aging Stud. 2012, 26, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, D.M.; Whelan, T.A. The relationship between grandparent satisfaction, meaning, and generativity. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 66, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noriega, C.; Velasco, C.; López, J. Perceptions of grandparents’ generativity and personal growth in supplementary care providers of middle-aged grandchildren. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T. Generativity in later life: Perceived respect from younger generations as a determinant of goal disengagement and psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 64, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajli, M.N.; Shanmugam, M.; Hajli, A.; Khani, A.H.; Wang, Y. Health care development: Integrating transaction cost theory with social support theory. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2015, 40, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Hayslip, B.; Kaminiski, P.L. Variability in the need for formal and informal social support among grandparent caregivers: A pilot study. In Custodial Grandparenting: Individual, Cultural, and Ethnic Diversity; Hayslip, B.H., Jr., Patrick, J.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski, J.A. Resourcefulness. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 1551–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roth, A.R. Informal caregiving and social capital: A social network perspective. Res. Aging 2020, 42, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Ajrouch, K.J.; Birditt, K.S. The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, H.R.; Ajrouch, K.J.; Antonucci, T.C. The Convoy Model and later-life family relationships. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2020, 12, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Mao, W.; Lee, Y.; Chi, I. The impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents’ physical health outcomes: The role of intergenerational support. Res. Aging 2017, 39, 612–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Smith, J.P. Hukou system, mechanisms, and health stratification across the life course in rural and urban China. Health Place 2019, 58, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Guan, L.; Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Fu, M.; He, H.; Wang, X. Depression among Chinese older adults: A perspective from Hukou and health inequities. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 223, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P. Floaters, settlers, and returnees: Settlement intention and hukou conversion of China’s rural migrants. China Rev. 2018, 18, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. Intergenerational intimacy and descending familism in rural North China. Am. Anthropol. 2016, 118, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. Migrating (grand) parents, intergenerational relationships and neo-familism in China. J. Comp. Soc. Work 2018, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.; Wu, Y.; Mao, Z.; Liang, X. Association of formal and informal social support with health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Treiman, D.J. Social origins, hukou conversion, and the wellbeing of urban residents in contemporary China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 42, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Abraido-Lanza, A.F.; Dohrenwend, B.P.; Ng-Mak, D.S.; Turner, J.B. The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adams-Price, C.E.; Nadorff, D.K.; Morse, L.W.; Davis, K.T.; Stearns, M.A. The creative benefits scale: Connecting generativity to life satisfaction. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2018, 86, 242–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, B.; Zhan, H. Filial piety and functional support: Understanding intergenerational solidarity among families with migrated children in rural China. Ageing Int. 2012, 37, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Burton, J.; Lonne, B. Informal kin caregivers raising children left behind in rural China: Experiences, feelings, and support. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 25, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirke, E.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Association between caring for grandchildren and feelings of loneliness, social isolation and social network size: A cross-sectional study of community dwelling adults in Germany. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, F.; Tang, Y. Hukou status and social exclusion of rural–urban migrants in transitional China. J. Asian Public Policy 2010, 3, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, J.T.; Schulz, R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol. Ageing 1996, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, D.M.; Kelley, S.J.; Lamis, D.A. Depression, social support, and mental health: A longitudinal mediation analysis in African American custodial grandmothers. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 82, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbin-MacNab, M.; Roberto, K.; Finney, J. Formal social support: Promoting resilience in grandparents parenting grandchildren. In Resilient Grandparent Caregivers: A Strengths-Based Perspective; Hayslip, B.J., Smith, G.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Hanley, J. Rural-to-urban migration, family resilience, and policy framework for social support in China. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2015, 9, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.C.L.; Tsang, B.Y.; Chokkanathan, S. Intergenerational reciprocity reconsidered: The honour and burden of grandparenting in urban China. Intersect. Gend. Sex. Asia Pac. 2016, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Smith, J.P. The citizenship advantage in psychological well-being: An examination of the Hukou system in China. Demography 2021, 58, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, E.C.L. Raising the precious single child in urban china-an intergenerational joint mission between parents and grandparents. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2006, 4, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Migrant (N = 508) | Local (N = 505) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 32.3 | 24.2 |

| Female | 67.7 | 75.8 | |

| Mean/SD | Mean/SD | ||

| Age (years) | Range: 40–93 | 56.5/8.7 | 60.5/5.6 |

| Education | Primary school | 67.1 | 58.0 |

| Junior school | 27.5 | 30.5 | |

| High school | 5.2 | 9.9 | |

| College or above | 0.2 | 1.6 | |

| Marriage | Married | 88.4 | 92.5 |

| Divorced | 2.8 | 1.0 | |

| Widowed | 8.9 | 6.5 | |

| Monthly income | 0–2500 | 62.2 | 55.0 |

| (RMB) | 2501–5000 | 27.0 | 35.2 |

| Above 5001 | 10.8 | 9.7 | |

| Chronic disease | Yes | 17.7 | 35.6 |

| No | 82.3 | 64.4 | |

| Medical insurance | Yes | 9.5 | 95.8 |

| No | 90.5 | 4.2 | |

| Social security | Yes | 44.7 | 87.7 |

| No | 55.3 | 12.3 |

| Range | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Domestic generative acts | 1–5 | 3.675 | 1.056 | 1 | |||

| 2. Informal social support | 1–5 | 4.177 | 0.835 | 0.230 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Formal social support | 1–5 | 1.949 | 1.041 | 0.077 * | 0.248 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Life satisfaction | 1–5 | 3.448 | 0.915 | 0.156 ** | 0.419 ** | 0.240 ** | 1 |

| Hukou Status | M | S.D. | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic generative acts | Migrant | 3.526 | 0.920 | 4.544 *** |

| Local | 3.825 | 1.157 | ||

| Informal social support | Migrant | 4.000 | 0.836 | 6.919 *** |

| Local | 4.355 | 0.797 | ||

| Formal social support | Migrant | 1.787 | 0.993 | 5.011 *** |

| Local | 2.111 | 1.063 | ||

| Life satisfaction | Migrant | 3.323 | 0.944 | 4.399 *** |

| Local | 3.574 | 0.867 |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic generative acts | Take care in illness | 0.864 |

| Take care in daily life | 0.921 | |

| Babysit grandchildren | 0.838 | |

| Do housework | 0.713 | |

| Informal social support | Family support | 0.749 |

| Friend support | 0.944 | |

| Significant others | 0.625 | |

| Formal social support | Community activities | 0.862 |

| State subsidies | 0.766 | |

| NGO services | 0.932 | |

| Professional consultation | 0.901 | |

| Life satisfaction | Close to ideal | 0.756 |

| Excellent condition | 0.813 | |

| Satisfied with life | 0.858 | |

| Important things | 0.896 | |

| Change nothing | 0.763 |

| Variable | Model 1 (Informal Social Support) | Model 2 (Formal Social Support) | Model 3 (Life Satisfaction) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

| Gender | −0.054 | 0.059 | −0.921 | −0.228 | 0.074 | −3.084 ** | 0.100 | 0.061 | 1.645 |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.004 | 1.470 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 3.299 ** | 0.005 | 0.004 | 1.229 |

| Education | −0.008 | 0.039 | −0.209 | 0.028 | 0.049 | 0.559 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.969 |

| Marriage | 0.051 | 0.048 | 1.068 | 0.006 | 0.060 | 0.104 | 0.007 | 0.049 | 0.146 |

| Monthly income | 0.069 | 0.040 | 1.711 | 0.110 | 0.050 | 2.184 * | 0.108 | 0.041 | 2.618 ** |

| Chronic disease | 0.016 | 0.058 | 0.279 | 0.011 | 0.073 | 0.155 | −0.025 | 0.060 | −0.420 |

| Local medical care | 0.185 | 0.062 | 2.977 ** | 0.071 | 0.078 | 0.914 | −0.007 | 0.108 | −0.062 |

| Local social security | 0.125 | 0.063 | 1.999 * | 0.369 | 0.078 | 4.697 *** | 0.123 | 0.065 | 1.901 |

| Domestic generative acts | 0.179 | 0.024 | 7.335 *** | 0.087 | 0.031 | 2.851 ** | 0.057 | 0.026 | 2.229 * |

| Informal social support | 0.475 | 0.045 | 10.603 *** | ||||||

| Formal social support | 0.100 | 0.038 | 2.663 ** | ||||||

| Hukou | 0.661 | 0.289 | 2.287 * | ||||||

| Informal social support*Hukou | −0.177 | 0.065 | −2.715 ** | ||||||

| Formal social support*Hukou | 0.030 | 0.051 | 0.587 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.090 | 0.080 | 0.218 | ||||||

| F | 11.044 *** | 9.749 *** | 19.921 *** | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Ngai, S.S.-y. Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction among Supplementary Grandparent Caregivers in Urban China: Mediated by Social Support and Moderated by Hukou Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211788

Guo H, Ngai SS-y. Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction among Supplementary Grandparent Caregivers in Urban China: Mediated by Social Support and Moderated by Hukou Status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211788

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Haoyi, and Steven Sek-yum Ngai. 2021. "Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction among Supplementary Grandparent Caregivers in Urban China: Mediated by Social Support and Moderated by Hukou Status" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211788

APA StyleGuo, H., & Ngai, S. S.-y. (2021). Domestic Generative Acts and Life Satisfaction among Supplementary Grandparent Caregivers in Urban China: Mediated by Social Support and Moderated by Hukou Status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211788