Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection of Studies

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Regulation of Medical Products in Africa

Regulatory Harmonization Process in Africa

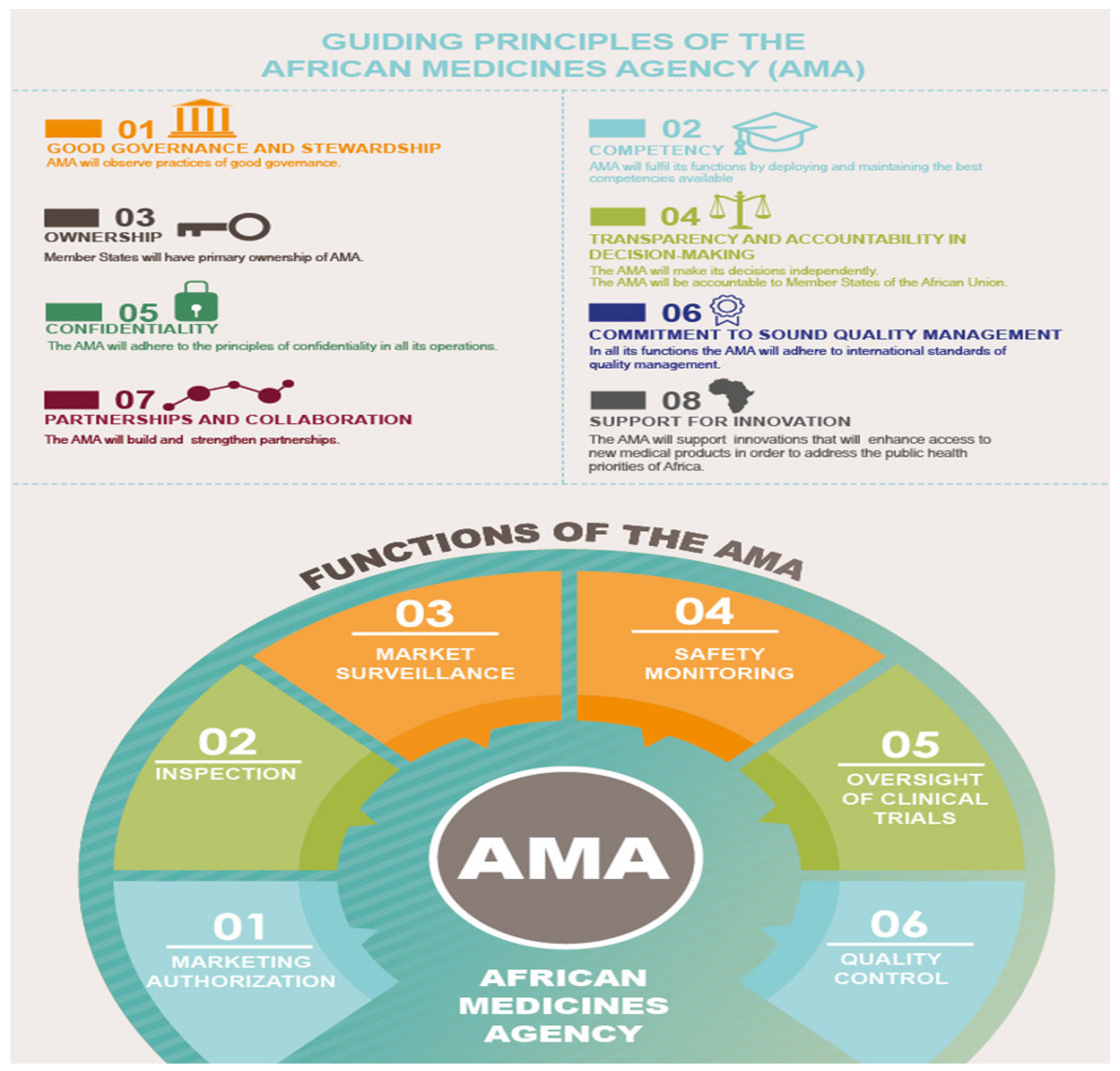

3.2. Evolution of African Medical Agency (AMA)

3.3. The Growing Importance of Global Health Diplomacy in Africa

Establishment of African Medicines Agency

3.4. Anticipated Benefits and Advantages of Fully Functional AMA

3.4.1. Growth of Local Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Capacity

3.4.2. Promoting Regulatory Cooperation and Harmonization

- a.

- Adopting AMRH’s workstreams, AMA would facilitate the medicines evaluation and registration through Common Technical Document formation. Currently, the marketing authorization can vary from 4 to 7 years in line with the resourcefulness of the individual NMRA. This lengthy period has adversely impacted the pharmaceutical companies in supplying medicines to the continent [37]. Mary Ampomah, President and CEO of the Global Alliance of Sickle Cell Disease Organizations (GASCDO) stressed the value of getting access to safe drugs and a chance for a better life in Africa. She highlighted that the AMA would speed up the approval process, and as a result, the medicines will be available sooner to the people.

- b.

- Although adopted in February 2019 by the member states of AU, as of February 2021, only eight members out of the required fifteen member states have ratified; a required legal process before AMA could come into effect. One of the challenging factors is the lack of legislation and how it would affect the activity and authority of NMRA in any given member state. However, learning from Ghana’s experience in harmonizing their legislation to AMA, member states must provide the required coordination and recognition of common purpose from the Ministry of Health (parent ministry), current Government, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Office of Attorney General [38]. Despite being a complex process, this now forms the legitimate platform effort to adopt and utilize AMA’s objectives to benefit Ghana’s population. This is paramount as there is a major variation among what is being regulated by NMRAs across Africa. As noted by Ndomondo-Sigonda et al., out of 26 NMRAs, only 15% are mandated to perform every regulatory activity, while 65% control veterinary medicines, 69% regulate herbal medicines, and more than two-thirds regulate items that include foods, pesticides, poisons, bottled water, cosmetics, and animal food supplements [37]. Therefore, harmonization through a common regulatory framework can prevent further delays in bringing important medicines to the public.

- c.

- Other regulatory functions of pharmacovigilance (PV) also showed a significant gap as only eight countries out of 26 sub-Saharan African countries had collected data on adverse events. Varying proportions of countries showed poor post-marketing surveillance (PMS), leading to SSFFCs (substandard, spurious, falsely labeled, falsified, and counterfeit) medicines being available in the market. AMA is expected to ease the process by bringing different technology strengths, technical expertise, and shared human and financial resources.

- d.

- Impact on training and education: The establishment of RCOREs meets training and education standards as these RCOREs possess the expertise on one or more aspects of the capacity building for NMRAs, i.e., training, education, regulatory, manufacturing, quality assurance, and control.

3.4.3. Continental Relevance of Priorities

3.4.4. Information Availability

3.4.5. Ensuring Robust Response to Counterfeit Medicine

4. Discussion

4.1. Enhancing the Role of a Clinical Trial in Shaping the Population Health

4.2. Greater Coordination among African Countries

4.3. Efficient Implementation of Intellectual Property Rights

4.4. South–South Cooperation and African Medical Agency

4.5. Impact of India’s Health Diplomacy

4.6. Impact of China’s Health Diplomacy

4.7. Future of Africa with African Medicines Agency in Action

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- World Population Review. Africa Population. 2019. Available online: http://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/africa-population (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. Our World in Data. The Burden of Disease. 2019. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Chattu, V.K.; Knight, W.A.; Adisesh, A.; Yaya, S.; Reddy, K.S.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Aginam, O.; Aslanyan, G.; Clarke, M.; Massoud, M.R.; et al. Politics of disease control in Africa and the critical role of global health diplomacy: A systematic review. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infomineo. Africa Continental Free Trade Area: Benefits, Costs, and Implications. 2019. Available online: https://infomineo.com/africa-continental-free-trade-area/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- The World Health Organization. Improving the Quality of Medical Products for Universal Access. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/fact-figures-qual-med/en/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Rägo, L.; Sillo, H.; T’Hoen, E.; Zweygarth, M. Regulatory framework for access to safe, effective quality medicines. Antivir. Ther. 2014, 19, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- African Union. Africa Health Strategy 2016–2030. Addis Ababa: African Union. 2016. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/newsevents/workingdocuments/27513-wd-sa16951_e_africa_health_strategy-1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagell, A.; Bourke Dowling, S. Scoping Review of Literature on the Health and Care of Mentally Disordered Offenders; CRD Report 16; NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Health 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sucharew, H.; Macaluso, M. Methods for Research Evidence Synthesis: The Scoping Review Approach. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 14, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Assessment of Medicines Regulatory Systems in Sub-Saharan African Countries. An Overview of Findings from 26 Assessment Reports; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization. Capacity Building: WHO—Prequalification of Medicines Programme. 2019. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/prequal/content/capacity-building-0 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Miot, J.; Naidoo, S.; Masota, N.E.; Ng’Andu, B.; Ngum, N.; Kaale, E. Harmonization of medical products regulation: A key factor for improving regulatory capacity in the East African Community. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Miot, J.; Naidoo, S.; Ambali, A.; Dodoo, A.; Mkandawire, H. The African medicines regulatory harmonization initiative: Progress to date. Med. Res. Arch. 2018, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The African Union. Decisions and Declarations, Assembly of the African Union, Fourth Ordinary Session. In Assembly/AU/Dec.55–72 (IV) Assembly/AU/Decl.1–2 (IV); The African Union: Abuja, Nigeria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The African Union. African Medicines Agency—Business Plan; The African Union: Abuja, Nigeria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Ambali, A. The African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Initiative: Rationale and Benefits. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The African Union. AU Model Law on Medical Products Regulation. 2016. Available online: http://thegreentimes.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ModellawMedicalProductsRegulationEnglishVersion.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- République du Burundi. Decret No 100/150 du 30 Septembre 1980 Portant Organisation de L’Exercice de la Pharmacie; Ministère de la Santé Publique: Bujumbura, Burundi, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- The African Union. Decisions, Executive Council, Twenty-Sixth Ordinary Session. Addis Ababa: EX.CL/Dec.851–872(XXVI); The African Union: Abuja, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Health Policy Watch. Ratification of Africa Medicines Agency Treaty Inches Forward—Africa CDC Head Calls It ‘Much-Needed’. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/ratification-of-africa-medicines-agency-treaty-inches-forward-africa-cdc-head-calls-it-much-needed/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Pyzik, O. Why the African Medicines Agency? Why Now? Africa Health Agenda International Conference 2021. March 2021. Virtual Conference. Available online: https://fightthefakes.org/why-the-african-medicines-agency-why-now/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Koplan, J.P.; Bond, T.C.; Merson, M.H.; Reddy, K.S.; Rodriguez, M.H.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Wasserheit, J.N. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009, 373, 1993–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, T.M. Health Diplomacy in Pandemical Times. Int. Organ. 2020, 74, E78–E97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitutive Act of Africa. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/34873-file-constitutiveact_en.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Penfold, E.D.; Fourie, P. Regional health governance: A suggested agenda for Southern African health diplomacy. Glob. Soc. Policy Interdiscip. J. Public Policy Soc. Dev. 2015, 15, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- African Union. Available online: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20190209/africas-leaders-gather-launch-new-health-financing-initiative-aimed-closing (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- WHO. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/african-island-states-launch-joint-medicines-procurement-initiative (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Onzivu, W. Regionalism and the reinvigoration of global health diplomacy: Lessons from Africa. Asian J. WTO Int. Health Poly. 2012, 7, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty for the Establishment of the African Medicines Agency. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36892-treaty-0069_-_ama_treaty_e.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Dave, V. The African Union’s Impact on Access to Medicines in Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Miot, J.; Naidoo, S.; Dodoo, A.; Kaale, E. Medicines Regulation in Africa: Current State and Opportunities. Pharm. Med. 2017, 31, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IFPMA-IAPO Webinar: The African Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vFT14mhhcVE (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- University of Oxford. Medical Product Quality Report—COVID-19 Vaccine Issues; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Chattu, V.K. Prioritizing ‘Equity’ in COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution through Global Health Diplomacy. Health Promot. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- UN COVID-19 Response. Supply Chain and COVID-19: UN Rushes to Move Vital Equipment to Frontlines. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/supplychain-and-covid-19-un-rushes-move-vital-equipmentfrontlines (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- TRIPS and Public Health, Module X, World Trade Organization. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ta_docs_e/modules10_e.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Monirul Azam, M. The Implementation of the TRIPS Agreement by Least Developed Countries: Preserving Policy Space for Innovation and Access to Medicines, 25 February 2021, Webinar; The Graduate Institute: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chattu, V.K.; Singh, B.; Kaur, J.; Jakovljevic, M. COVID-19 Vaccine, TRIPS, and Global Health Diplomacy: India’s Role at the WTO Platform. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6658070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killeen, O.J.; Davis, A.; Tucker, J.D.; Meier, B.M. Chinese Global Health Diplomacy in Africa: Opportunities and Challenges. Global Health Gov. 2018, 12, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gauttam, P.; Singh, B.; Kaur, J. COVID-19 and Chinese Global Health Diplomacy: Geopolitical Opportunity for China’s Hegemony? Millenn. Asia 2020, 11, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, V. Indian health diplomacy in East Africa: Exploring the potential in pharmaceutical manufacturing. S. Afr. J. Int. Aff. 2019, 26, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tediosi, F.; Finch, A.; Procacci, C.; Marten, R.; Missoni, E. BRICS countries and the global movement for universal health coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2015, 31, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vardhan, H. Business Standard. (7 March 2021). We are in the Endgame of COVID-19 Pandemic in India. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/we-are-in-the-endgame-of-covid-19-pandemic-in-india-vardhan-121030700609_1.html (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Chakrabarti, K. (9 July 2020). India’s Medical Diplomacy during COVID-19 through South-South Cooperation. Observer Research Foundation. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-medical-diplomacy-during-covid19-through-south-south-cooperation-69456/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Mol, R.; Singh, B.; Chattu, V.K.; Kaur, J.; Singh, B. India’s Health Diplomacy as a Soft Power Tool towards Africa: Humanitarian and Geopolitical Analysis. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2021, 56, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, H.V.; Abhishek, M. (2 June 2020). India, China and Fortifying the Africa Outreach. The Hindu. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/india-china-and-fortifying-the-africa-outreach/article31725783.ece (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- MEA Minister Jaishankar Speaks to His Counterparts from African Countries. Hindustan Times (26 April 2020). Available online: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/mea-minister-jaishankar-speaks-to-his-counterparts-from-african-countries/story-1tArB3sAVz3ZzTdrZNrFXP.html (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Ministry of External Affairs. Govt of India (28 April 2021). Vaccine Supply. Available online: https://www.mea.gov.in/vaccine-supply.htm (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Manju, S. (16 November 2019). India-Africa Cooperation in the Healthcare Sector. The Diplomatist. Available online: https://diplomatist.com/2019/11/16/india-africa-cooperation-in-the-healthcare-sector (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Laxmi, Y. (26 February 2018). African Union to Come Up with African Medicine Agency to Harmonise Drug Regulation of Member states. PHARMABIZ.com. Available online: http://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid=107496&sid=1#:~:text=Piyush%20Gupta%2C%20associate%20director%2C%20GNH,regulatory%20compliance%20in%20African%20countries (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Maddalena, P. (7 April 2020). China’s Health Diplomacy in Africa: Pitfalls Behind the Leading Role. Italian Institute for International Political Studies. Available online: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/chinas-health-diplomacy-africa-pitfalls-behind-leading-role-25694 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Jing, X.; Liu, P.; Guo, Y. Health Diplomacy in China. Global Health Gov. 2011, 4. Available online: http://www.ghgj.org/JingPeilongYan.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Meidan, M. China’s Africa Policy: Business Now, Politics Later. Asian Perspect. 2006, 30, 69–93. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/42704565 (accessed on 19 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kharsany, S. (11 March 2021). Why an African Medicines Agency? Now More Than Ever! Health Policy Watch. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/african-medicines-agency/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Ncube, B.M.; Dube, A.; Ward, K. Establishment of the African Medicines Agency: Progress, challenges and regulatory readiness. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2021, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, A. How COVID spurred Africa to plot a vaccines revolution. Nature 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NEPAD. African Union Model Law on Medical Products Regulation and Harmonisation; African Union Development Agency: Midrand, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, A. Assessment of Potential Barriers to Medicines Regulatory Harmonization in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Region. Ph.D Thesis, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016; pp. 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Issue Brief. African Union Model Law for Medical Products Regulation: Increasing Access to and Delivery of New Health Technologies for Patients in Need. pp. 1–12. Available online: http://adphealth.org/upload/resource/AUModelLaw.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- NEPAD Agency; PATH. Increasing Access to High-Quality, Safe Health Technologies Across Africa: African Union Model Law on Medical Products Regulation. 2016. Available online: https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/APP_au_model_law_br.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Luthuli, N.; Robles, W. Africa Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Initiatives; WCG: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Makoni, M. African Medicines Agency to be established. Lancet 2021, 398, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattu, V.K.; Pooransingh, S.; Allahverdipour, H. Global health diplomacy at the intersection of trade and health in the COVID-19 era. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghizade, S.; Chattu, V.K.; Jaafaripooyan, E.; Kevany, S. COVID-19 Pandemic as an Excellent Opportunity for Global Health Diplomacy. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 655021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binagwaho, A.; Mathewos, K.; Davis, S. Equitable and Effective Distribution of the COVID-19 Vaccines—A Scientific and Moral Obligation. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisenyane, S.M.; Hendricks, S.J.H.; Fineberg, H. Understanding how domestic health policy is integrated into foreign policy in South Africa: A case for accelerating access to antiretroviral medicines. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1339533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S. No | Broader Function | Specific Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coordinate (5) |

|

| 2 | Convene (1) |

|

| 3 | Designate (1) |

|

| 4 | Develop (1) |

|

| 5 | Evaluate (1) |

|

| 6 | Examine (1) |

|

| 7 | Monitor (1) |

|

| 8 | Promote (3) |

|

| 9 | Provide (4) |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chattu, V.K.; Dave, V.B.; Reddy, K.S.; Singh, B.; Sahiledengle, B.; Heyi, D.Z.; Nattey, C.; Atlaw, D.; Jackson, K.; El-Khatib, Z.; et al. Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211758

Chattu VK, Dave VB, Reddy KS, Singh B, Sahiledengle B, Heyi DZ, Nattey C, Atlaw D, Jackson K, El-Khatib Z, et al. Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211758

Chicago/Turabian StyleChattu, Vijay Kumar, Vishal B. Dave, K. Srikanth Reddy, Bawa Singh, Biniyam Sahiledengle, Demisu Zenbaba Heyi, Cornelius Nattey, Daniel Atlaw, Kioko Jackson, Ziad El-Khatib, and et al. 2021. "Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211758

APA StyleChattu, V. K., Dave, V. B., Reddy, K. S., Singh, B., Sahiledengle, B., Heyi, D. Z., Nattey, C., Atlaw, D., Jackson, K., El-Khatib, Z., & Eltom, A. A. (2021). Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211758