Asymmetric Effects of Quality of Life on Residents’ Satisfaction: Exploring a Newborn Natural Disaster Tourism Destination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Residents’ QOL Attributes in NNDDs

2.2. Residents’ Satisfaction toward NNDD Development

2.3. The Relationship between QOL Attributes and Residents’ Satisfaction

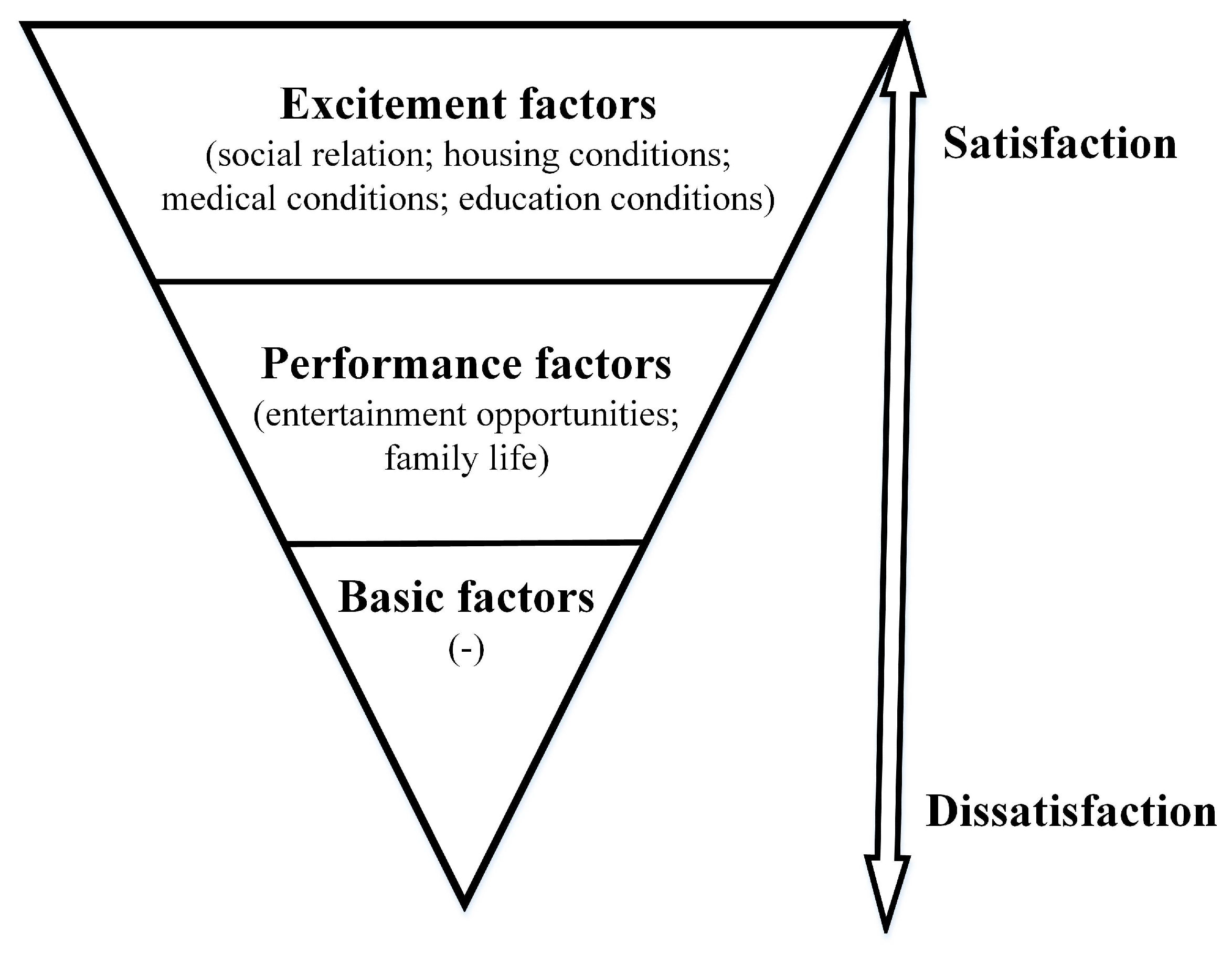

2.4. The Three-Factor Theory of Customer Satisfaction

3. Methods

3.1. Phase One: Qualitative Study

I started my restaurant seven or eight years ago, and at that time, just after the earthquake, there were not many other jobs, and the medicine business was not good. After seeing more tourists come, the tourism development improved, and I opened the restaurant. However, now there are fewer tourists, and business is not good. [Interviewee 3]

3.2. Phase Two: Quantitative Study

3.2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Asymmetric Effects Analysis

5. Discussion and Implication

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faulkner, B. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yin, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, M.; Huang, S. “Blessing in disguise”: The impact of the Wenchuan earthquake on inbound tourist arrivals in Sichuan, China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Unpacking visitors’ experiences at dark tourism sites of natural disasters. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.C.; Hughes, M. Tourism Market Recovery in the Maldives after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Ritchie, B.W.; Walters, G. Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Eichhorn, V. Consuming post-disaster destinations: The case of Sichuan, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, G. Reconstruction strategies after the Wenchuan Earthquake in Sichuan, China. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, D.; Wang, Y.L.; Shi, Z.W. A measurement framework of community recovery to earthquake: A Wenchuan earth-quake case study. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Residents’ perceptions of community-based disaster tourism: The case of Yingxiu, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D. Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM 2). Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Sharpley, R. Local community perceptions of disaster tourism: The case of L’Aquila, Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, E.; Shiozaki, Y. Towards a policy that supports people-centered housing recovery: Learning from housing recon-struction after the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Kobe, Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.S.; Gonzalez, C.; Hutter, M. Phoenix tourism within dark tourism newborn, rebuilding and rebranding of tourist destinations following disasters. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 196–215. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, K.-J.; Lee, C.-K. Determining the Attributes of Casino Customer Satisfaction: Applying Impact-Range Performance and Asymmetry Analyses. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. Using a revised importance–performance analysis approach: The case of Taiwanese hot springs tourism. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, M. Examining the asymmetric effect of multi-shopping tourism attributes on overall shopping destination sat-isfaction. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Bai, K.; Ma, Y.F.; Zhuang, Y. The asymmetric effect of the attribute-level performance of themed scenic spots on tourist satisfaction: An empirical analysis of four historical and cultural themed scenic spots. Tour. Trib. 2014, 29, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Destination attribute effects on rock climbing tourist satisfaction: An Asymmetric Impact-Performance Analysis. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M. A comparison of service quality attributes for stand-alone and resort-based luxury hotels in Macau: 3-Dimensional importance-performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.Q.; Deng, J.Y.; Pierskalla, C.; King, B. Urban tourism attributes and overall satisfaction: An asymmetric im-pact-performance analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M. Comparing residents’ and tourists’ emotional solidarity with one another: An extension of Durkheim’s model. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Hui, T.-K. Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G. Exploring the Nature of Tourism and Quality of Life Perceptions among Residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Anwar, O.; Ye, J.; Orabi, W. Efficient Optimization of Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Transportation Networks. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30, 04015047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Kolade, O.; Kibreab, G. Post-disaster Housing Reconstruction: The Impact of Resourcing in Post-cyclones Sidr and Aila in Bangladesh. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 934–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; OuYang, Z. Disaster risk, risk management, and tourism competitiveness: A cross-nation analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Wu, K.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J. Two Sides of a Coin: A Crisis Response Perspective on Tourist Community Participation in a Post-Disaster Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. Debating Sustainability in Tourism Development: Resilience, Traditional Knowledge and Community: A Post-disaster Perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xie, Z.; Peng, Y.; Song, Y.; Dai, S. How Can Post-Disaster Recovery Plans Be Improved Based on Historical Learning? A Comparison of Wenchuan Earthquake and Lushan Earthquake Recovery Plans. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E.; Ritchie, B.W. VFR Travel: A Viable Market for Tourism Crisis and Disaster Recovery? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ Satisfaction with Community Attributes and Support for Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Weiermair, K. Destination Benchmarking: An Indicator-System’s Potential for Exploring Guest Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Garau, J. The Factor Structure of Tourist Satisfaction at Sun and Sand Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Nagao, K.; He, Y.; Morgan, F.W. Satisfiers, dissatisfiers, criticals, and neutrals: A review of their relative effects on customer (dis)satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2007, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must be quality. Hinshitsu 1984, 14, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Padula, G.; Busacca, B. The asymmetric impact of price-attribute performance on overall price evaluation. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2005, 16, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krešić, D.; Mikulić, J.; Miličević, K. The Factor Structure of Tourist Satisfaction at Pilgrimage Destinations: The Case of Medjugorje. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.-W.; Stewart, W. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhao, L.; Huang, S. Backpacker Identity: Scale Development and Validation. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brus, D.J.; Nieuwenhuizen, W.; Koomen, A. Can we gain precision by sampling with probabilities proportional to size in surveying recent landscape changes in the Netherlands? Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006, 122, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, K.; Byon, K.K.; Baek, W.; Williams, A.S. Examining structural relationships among sport service environments, excitement, consumer-to-consumer interaction, and consumer citizenship behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, D.R. How Service Marketers can Identify Value-Enhancing Service Elements. J. Serv. Mark. 1988, 2, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J.; Matzler, K. Customer delight and market segmentation: An application of the three-factor theory of customer satis-faction on life style groups. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulić, J.; Prebežac, D. Using dummy regression to explore asymmetric effects in tourist satisfaction: A cautionary note. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| QOL Domains | Scale Items | References | NNDD Context | Resident Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Conditions | Moved into a new house | √ | √ | |

| Home was spacious | √ | |||

| Well-equipped facilities (water, gas, electricity) | [42] | √ | ||

| Residential architecture highlights local culture | √ | |||

| Housing function combination commercial and residential | √ | √ | ||

| Work Income | Enough good jobs for residents | [24,25,42] | √ | |

| Selling local specialty products | √ | √ | ||

| Stores and restaurants owned by residents | [24,35] | √ | √ | |

| Explaining disaster heritage and memorial halls | √ | √ | ||

| High community wage | [24] | |||

| Life Facilities | Public transportation to and from other communities | [26,42] | √ | √ |

| Roads, bridges, and utility services facilities | [24,35] | √ | √ | |

| Shopping facilities | [42] | |||

| Plenty of parks and open space | [24] | √ | ||

| Exercising facility | √ | |||

| Medical and Education | Community hospital facilities were advanced | [24,42] | √ | √ |

| Medical supplies were adequate | [42] | √ | ||

| Going to the hospital was convenient | √ | |||

| New schools were stronger | √ | √ | ||

| The government provides free employment skills training | [42] | √ | √ | |

| Family Life | Family relationships were harmonious | [24] | √ | √ |

| Family ties were stronger | √ | √ | ||

| Family members take care of each other | √ | √ | ||

| More time to exercise | [25] | √ | ||

| Life was relaxed and happy | [25,26] | √ | ||

| Health and Safety | Environmental cleanliness (air, water, soil) | [26,42] | √ | |

| The beauty of my community | [24] | √ | ||

| The earthquake resistance level of the building was improved | √ | √ | ||

| The mountain was strengthened | √ | √ | ||

| The flood levee was reinforced | √ | √ | ||

| Social Relations | Harmonious neighbourhood | [24,42] | √ | √ |

| Opportunities to be with friends and relatives | [42] | √ | √ | |

| Opportunities to interact with tourists | [24] | √ | √ | |

| Exchange business experience | √ | |||

| Selling restaurants online | √ | |||

| Entertainment Opportunities | Publicly funded recreation | [42] | √ | √ |

| Plenty of festivals, fairs | [26] | √ | ||

| Spending on entertainment increased | √ | |||

| More entertainment activities | [35] | √ | ||

| Having sports events to participate in in my community | [26] | √ |

| Profile | Category | % | Profile | Category | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47.5 | Monthly income | Less than RMB 1000 | 32.5 |

| Female | 52.5 | RMB 1000–2000 | 35.6 | ||

| Age | 28–35 | 5.3 | RMB 2001–4000 | 21.9 | |

| 36–45 | 31.9 | More than RMB 4000 | 10.0 | ||

| 46–55 | 40.9 | Occupation | Individual businesses for tourism | 20.1 | |

| >55 | 21.9 | Tourism workers | 8.4 | ||

| Education | Junior high school or below | 58.8 | Transportation personnel | 1.8 | |

| High school or technical secondary school | 25.1 | Farmers | 34.8 | ||

| Junior college | 13.2 | Retired | 6.3 | ||

| Undergraduate or above | 2.9 | Teachers | 8.7 | ||

| Length of residence | <5 years | 14.2 | Personnel of enterprises and institutions | 6.6 | |

| 5–10 years | 7.4 | Other | 13.2 | ||

| 11–20 years | 12.9 | ||||

| >20 years | 65.4 |

| Dimensions of Attributes | Items of Scale | Exploratory Factor Analysis (N = 189) | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (N = 190) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | Eigenvalue (% of Variance) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Factor Loading | Individual Item Reliability (R2) | Composite Reliability | AVE | ||

| Work Income | Enough good jobs for residents | 0.768 | 7.101 (12.185%) | 0.817 | 0.711 | 0.506 | 0.837 | 0.5639 |

| Selling local specialty products | 0.764 | 0.826 | 0.682 | |||||

| Stores and restaurants owned by residents | 0.737 | 0.791 | 0.625 | |||||

| Explaining disaster heritage and memorial halls | 0.705 | 0.665 | 0.443 | |||||

| Social Relations | Harmonious neighborhood | 0.771 | 2.973 (11.913%) | 0.809 | 0.862 | 0.743 | 0.8353 | 0.5646 |

| Opportunities to be with friends and relatives | 0.756 | – | – | |||||

| Opportunities to interact with tourists | 0.707 | 0.721 | 0.519 | |||||

| Exchange business experience | 0.699 | 0.570 | 0.325 | |||||

| Selling restaurants online | 0.533 | 0.819 | 0.671 | |||||

| Housing Conditions | Moved into a new house | 0.736 | 2.309 (9.996%) | 0.792 | 0.796 | 0.633 | 0.847 | 0.5814 |

| Well-equipped facilities (water, gas, electricity) | 0.730 | 0.742 | 0.550 | |||||

| Residential architecture highlights local culture | 0.666 | 0.814 | 0.662 | |||||

| Housing function combination commercial and residential | 0.659 | 0.692 | 0.478 | |||||

| Medical Conditions | Community hospital facilities were advanced | 0.828 | 1.630 (9.225%) | 0.826 | 0.873 | 0.762 | 0.8677 | 0.6888 |

| Medical supplies were adequate | 0.808 | 0.907 | 0.823 | |||||

| Going to the hospital was convenient | 0.791 | 0.694 | 0.481 | |||||

| Entertainment Opportunities | Publicly funded recreation | 0.755 | 1.290 (8.396%) | 0.714 | 0.604 | 0.365 | 0.7985 | 0.6774 |

| Spending on entertainment increased | 0.685 | – | – | |||||

| More entertainment activities | 0.642 | 0.995 | 0.990 | |||||

| Having sports events to participate in in my community | 0.636 | – | – | |||||

| Family Life | Family relationships were harmonious | 0.754 | 1.162 (8.315%) | 0.711 | 0.629 | 0.396 | 0.7584 | 0.4412 |

| Family ties were stronger | 0.697 | 0.674 | 0.454 | |||||

| Family members take care of each other | 0.560 | 0.740 | 0.548 | |||||

| Life was relaxed and happy | 0.509 | 0.606 | 0.367 | |||||

| Education Conditions | New schools were stronger | 0.839 | 1.058 (7.365) | 0.789 | 0.807 | 0.651 | 0.764 | 0.6182 |

| The government provides free employment skills training | 0.810 | 0.765 | 0.585 | |||||

| Variable | WI | SR | HC | MC | EO | FL | EC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WI | 0.751 | ||||||

| SR | 0.241 ** | 0.751 | |||||

| HC | 0.319 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.762 | ||||

| MC | 0.201 ** | 0.178 * | 0.419 ** | 0.829 | |||

| EO | 0.405 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.823 | ||

| FL | 0.284 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.664 | |

| EC | 0.116 | 0.287 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.526 ** | 0.143 * | 0.396 ** | 0.786 |

| Variables of Attributes | Non-Standardized Regression Coefficients | SE | t-Value | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H _ Work Income (H _ WI) | 0.114 | 0.085 | 1.348 | 0.179 | 1.322 |

| L _ Work Income (L _ WI) | 0.022 | 0.056 | 0.397 | 0.692 | 1.350 |

| H _ Social Relations (H _ SR) | 0.129 * | 0.053 | 2.460 | 0.014 | 1.280 |

| L _ Social Relations (L _ SR) | −0.215 | 0.121 | −1.776 | 0.077 | 1.172 |

| H _ Housing Conditions (H _ HC) | 0.147 ** | 0.056 | 2.624 | 0.009 | 1.446 |

| L _ Housing Conditions (L _ HC) | −0.096 | 0.114 | −0.844 | 0.399 | 1.144 |

| H _ Medical Conditions (H _ MC) | 0.196 *** | 0.055 | 3.554 | 0.000 | 1.384 |

| L _ Medical Conditions (L _ MC) | −0.102 | 0.093 | −1.102 | 0.271 | 1.375 |

| H _ Entertainment Opportunities (H _ EO) | 0.321 *** | 0.081 | 3.958 | 0.000 | 1.354 |

| L _ Entertainment Opportunities (L _ EO) | −0.146 ** | 0.055 | −2.652 | 0.008 | 1.382 |

| H _ Family Life (H _ FL) | 0.394 *** | 0.056 | 6.979 | 0.000 | 1.429 |

| L _ Family Life (L _ FL) | −0.333 *** | 0.092 | −3.626 | 0.000 | 1.148 |

| H _ Education Conditions (H _ EC) | 0.118 * | 0.059 | 2.012 | 0.045 | 1.264 |

| L _ Education Conditions (L _ EC) | 0.457 | 0.245 | 1.866 | 0.063 | 1.167 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, D.; Jiang, Z.; Qu, H. Asymmetric Effects of Quality of Life on Residents’ Satisfaction: Exploring a Newborn Natural Disaster Tourism Destination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111577

Lin D, Jiang Z, Qu H. Asymmetric Effects of Quality of Life on Residents’ Satisfaction: Exploring a Newborn Natural Disaster Tourism Destination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111577

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Derong, Zuoming Jiang, and Hailin Qu. 2021. "Asymmetric Effects of Quality of Life on Residents’ Satisfaction: Exploring a Newborn Natural Disaster Tourism Destination" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111577

APA StyleLin, D., Jiang, Z., & Qu, H. (2021). Asymmetric Effects of Quality of Life on Residents’ Satisfaction: Exploring a Newborn Natural Disaster Tourism Destination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111577