Abstract

The aim of this meta-analysis was to quantify the change in sedentary time during the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on health outcomes in the general population. One thousand six hundred and one articles published after 2019 were retrieved from five databases, of which 64 and 40 were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis, respectively. Studies were grouped according to population: children (<18 years), adults (18–64 years) and older adults (>65 years). Average sedentary time was calculated, with sub-analyses performed by country, behaviour type and health outcomes. Children were most affected, increasing their sedentary time by 159.5 ± 142.6 min day−1, followed by adults (+126.9 ± 42.2 min day−1) and older adults (+46.9 ± 22.0 min day−1). There were no sex differences in any age group. Screen time was the only consistently measured behaviour and accounted for 46.8% and 57.2% of total sedentary time in children and adults, respectively. Increases in sedentary time were negatively correlated with global mental health, depression, anxiety and quality of life, irrespective of age. Whilst lockdown negatively affected all age groups, children were more negatively affected than adults or older adults, highlighting this population as a key intervention target. As lockdowns ease worldwide, strategies should be employed to reduce time spent sedentary. Trial registration: PROSPERO (CRD42020208909).

1. Introduction

Sedentary behaviour, defined as any activity in a seated or reclined posture expending ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs, [1]), is suggested to be an independent short- and long-term risk factor for markers of adiposity, cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes mellitus [2,3,4]. Similarly, prolonged bouts of uninterrupted sedentary time across the day are associated with significant health risks [3,5] that have been shown to persist irrespective of physical activity (PA) levels [1,6,7], although this remains contentious [8,9]. Indeed, even 10 min of uninterrupted sedentary time has been reported to decrease insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance and increase circulating triglyceride levels [1]. Of concern, however, the average North American child (8–18 years) engages in 75 h week−1 (or 10.7 h day−1) of multimedia use [10,11], with comparable levels reported in European [12] and Asian [13] children. Similar levels of sedentary time (up to 12.3 ± 1.4 h day−1) have been reported globally in adults [3,4]. Sedentary lifestyles, and the identification of strategies to reverse them, represent a significant public health challenge [14]. Moreover, the need to understand sedentary time and behaviour, and their relationship(s) with health outcomes, may be more important than ever with the emergence of novel Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19).

Since the pandemic was announced in December 2019, there have been in excess of 167 million cases and 3.5 million deaths across 216 countries, as of 24 May 2021 [15]. Whilst the global response has been far from homogeneous most countries have adopted some form of social distancing, homestay (or lockdown) requirements, self-isolation or quarantine measures to limit COVID-19 transmission, and relieve pressure on health care services [16]. Indeed, in April 2020, over 50% of the global population were subject to some form of government restrictions [15], many of which may have had unintended deleterious health consequences. More specifically, homestay strategies may have increased sitting and screen time, due to children participating in online learning and adults working from home [16], whilst decreasing opportunities to break-up prolonged periods of sedentary time/behaviour. The effects of COVID-19 and subsequent restrictions on habitual PA levels have received substantial attention, with a recent review reporting decreased levels of PA globally which was attributed to social distancing measures [17]. However, no review to date has considered the impact of these restrictions on sedentary time, or the associated behaviours.

Meyer et al. [18] reported that ≥8 h day−1 of screen time was associated with a greater likelihood of symptoms of depression, loneliness, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in 3052 American adults. However, in the same study, total sitting time was not associated with any mental health outcome [18], in accord with Ugboule et al. [19] who reported no associations between sedentary time and emotional well-being in 9142 similarly aged adults. Studies examining the effect of COVID-19 restrictions on sedentary time in children are also conflicting. Indeed, Kang et al. [20] reported trivial associations between sedentary time and mental health outcomes in 4898 Chinese adolescents (16.3 ± 1.3 years), whereas Lu et al. [21] reported a positive association between sedentary time and risk of insomnia, depression, and anxiety in 965 Chinese adolescents (15.3 ± 0.5 years). Moreover, it is pertinent to note the potential for geographically specific variations in this relationship between sedentary time and health outcomes, thereby limiting the conclusions that can be drawn on the basis of single-country analyses. Therefore, a review is urgently needed to consolidate our understanding of COVID-19′s impact on sedentary time/behaviour and associated health outcomes and thereby highlight avenues for future interventions and research.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to assess the influence of COVID-19 and associated government restrictions on sedentary time and/or behaviour and physical, mental, and social health outcomes in the general population. A secondary aim was to examine the strength of association between sedentary time and/or behaviour and health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42020208909) and conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [22,23]. An online search was conducted on 12 January 2021 across the following databases: EBSCOhost, Medline, SPORTDiscus, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection. A date limit was set as 2020–2021 to ensure that only articles concerning COVID-19 were collected. Across these databases, the key search terms were modified to individual requirements, with Boolean and MeSH terms used to search the following terms and their variations: “sedentary time”, “sedentary behaviour”, “screen time”, “sitting time”, “sedentary posture” AND “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV”, “2019 corona-virus”. The full search terms can be found in the online supplementary material. Two authors (AR and RK) initially screened all abstracts independently before reviewing full-text articles for inclusion. In cases where disagreements regarding the inclusion of a study were unable to be resolved, LS was consulted to reach a consensus, which occurred on three occasions. Of the three articles where there were disagreements, one was included in the final review.

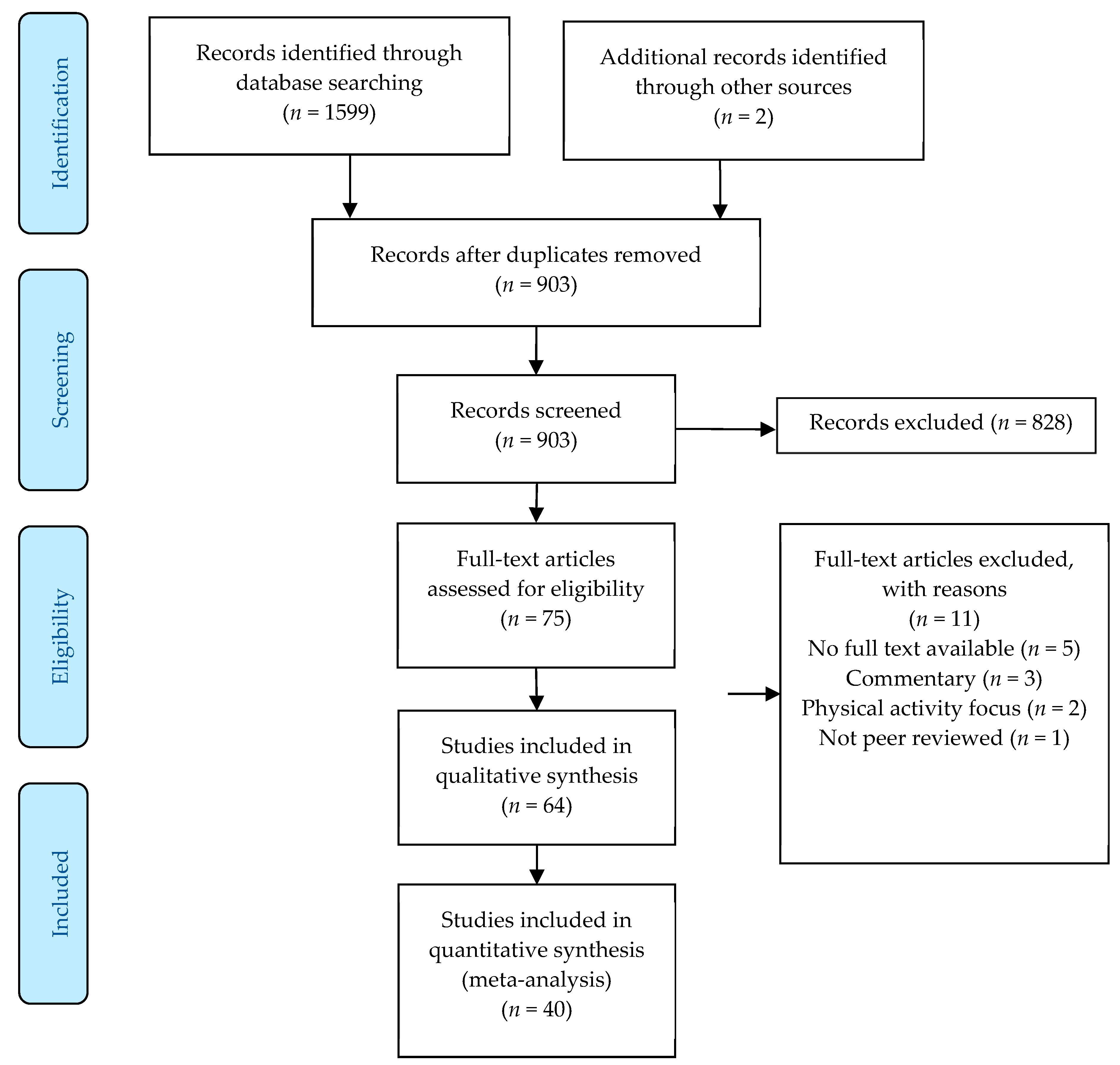

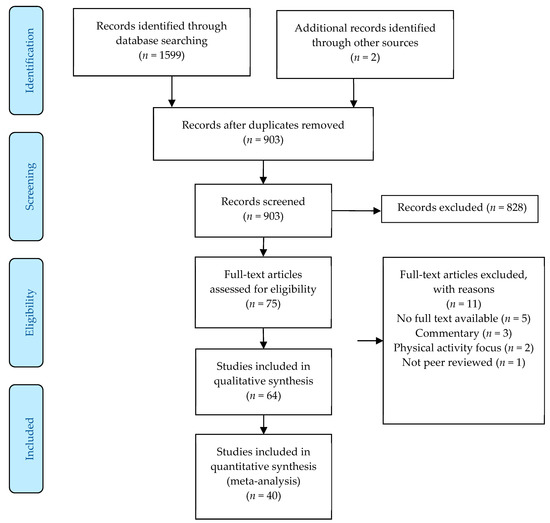

All studies assessing any type of sedentary behaviour or sedentary time (time spent below 1.5 METs but without verification of posture) using either subjective (questionnaires or interviews) or device-based (accelerometers or inclinometers) measures, in any population (children: <18 years of age, adults: >18 years of age, or older adults: >65 years of age), irrespective of methodological approach (cross-sectional, cohort, or longitudinal study designs), were included. Furthermore, adequate reporting of the restrictions in place at the time of data collection was required for inclusion to enable tentative comparisons to be made between geographical regions. All studies involving human participants and written in the English language which met the specified criteria were included, with any non-peer reviewed grey literature, including conference papers and theses, excluded. To be included within the meta-analysis studies had to provide data from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic so the impact of the pandemic could be assessed. Moreover, commentaries examining the potential detrimental effects of sedentary time and/or behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic were also excluded. The initial search gathered 1601 results (903 after the removal of duplicates), from which 828 were excluded during the title and abstract screening phase. Following full-text review, 64 articles were retained and included within the systematic review and 40 were utilized within the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic flow diagram of the systematic review and meta-analysis process.

2.2. Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Risk of Bias Appraisal

Data extraction from all included full-text articles was completed to obtain the following information: authors and year of publication, number and age of participants, country of study, COVID-19 restrictions in place at the time of data collection, sedentary time/behaviour measures, health outcome measures reported (if any), information required to assess risk of bias, and main results (Table 1 and Table 2). All researchers contributed to the synthesis of data. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook 5.1.0 for systematic reviews [24]. Briefly, for every included study, risk of bias was classified as ‘High’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Low’ or ‘Unclear/Not reported’ in the following areas: detection bias, attrition bias, selection bias, performance bias, selective reporting bias and other sources of bias. A brief rationale for the decision is included in the supplementary material, in line with previous studies [25,26], with the full risk of bias table available in Supplementary Information Table S1 and Table S2.

Table 1.

Data extraction of studies measuring sedentary time and/or behaviour during COVID-19 in children.

Table 2.

Data extraction of studies measuring sedentary time and/or behaviour during COVID-19 in adults and older adults.

The quality of evidence for each of the included studies was decided in a systematic manner with the aid of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [27], as used in previous reviews of this type [25,26]. The GRADE framework allows for the classification of research articles into four distinct categories (‘High’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Low’, and ‘Very Low’). Any study including a randomised recruitment and/or a longitudinal design starts at ‘High’, with all other study types and designs starting at ‘Low’. The quality of evidence was then downgraded if there were serious limitations hindering the interpretation of the study, such as high risk of bias, unvalidated data collection methods, and convenience sampling techniques [27]. Conversely, the quality of evidence was upgraded if there is no cause for the downgrading of the study and a large effect size and/or a dose–response relationship was evident within the study [27]. All included studies were synthesised in a systematic approach examining the effect of COVID-19 on overall sedentary time, and specific sedentary behaviours where appropriate. All results were divided into children, adult, and older adult specific segments due to the population-specific sedentary behaviour guidelines [14,28] and the potentially different impacts of government restrictions on these populations.

All meta-analyses were conducted in R (R Studio v1.2.2019, R Studio, Boston, MA, USA) using the meta and metagen packages and their dependencies. Where pre- and post-COVID data were available, the standardised mean difference (SMD) was calculated using the formula: difference between means/standard deviation of outcome [29]. Prior to calculating the SMD, all sedentary time and behaviour measurements were converted into minutes per day (mins day−1) to ensure all variables were reported on the same nominal scale. Time spent sedentary during COVID-19 was determined based on those studies that specifically reported the sedentary time of participants experiencing government restrictions and the post data in longitudinal studies. Subsequently, the average sedentary time between studies, and the pooled standard deviation, were calculated. Meta-analyses were conducted separately for both child, adult, and older adult data, and between sexes where the data were available, so that tentative inter-population comparisons could be made.

3. Results

There were 64 studies included within the review [18,20,21,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84], of which 19 studies included children with 5, 11, and 3 studies scoring high, moderate, and low quality, respectively, on the GRADE scale (Table S1). The remaining 45 studies were conducted with adults (2 in older adults) with 13, 28, and 4 studies scoring high, moderate, and low quality, respectively, on the GRADE scale (Table S2). The 64 studies included within this systematic review encompassed 282,202 participants (28.5 ± 17.1 years), of which 262,630 were adults (93.1%; 36.5 ± 5.5 years), 16,214 were children (5.7%; 11.5 ± 2.3 years) and 3358 older adults (1.2%; 60.6 ± 8.0 years). The majority of the studies were quantitative utilising online questionnaires (60/64; 93.8%), were observational or cross-sectional in design (61/64; 95.2%), had >100 participants (56/64; 87.5%), and recruited from the general population (53/64; 89.0%). Specific populations included elite athletes [43], post-bariatric patients [44], pregnant women [45], participants with depression [82], and children with autism [27], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, [28]), and obesity [29]. Finally, 25 studies (37.5%) were conducted in European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scotland, Spain, and the United Kingdom; [27,29,30,31,32,42,43,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]), 18 (28.1%) in Asia (Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, Jordan, Kuwait, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates; [20,21,28,33,34,35,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]), 12 (18.8%) in North America (Canada and United States; [18,36,37,38,39,40,41,75,76,77,78,79]), 8 (11.0%) in South America (Brazil and Chile; [44,46,80,81,82,83,85,86]), and 1 (1.6%) in Africa (Ghana; [84]).

Overall, participants increased their sedentary time during the COVID-19 pandemic by 135.0 ± 46.0 min day−1, however there was a significant difference between children and adults (Table 1 and Table 2, respectively), with children increasing their sedentary time more than adults (+159.5 ± 142.6 min day−1 vs. +126.9 ± 42.2 min day−1, p < 0.05). Only two studies investigated changes in sedentary time in older adults, reporting a non-significant increase of 46.9 ± 22.0 min day−1 (Table 2). These increases were found regardless of restrictions currently in place at the time of data collection. Such increases in sedentary time resulted in children, adults and older adults spending 383.9 ± 138.2 min day−1, 510.5 ± 167.9 min day−1 and 586.3 ± 25.2 min day−1 being sedentary, respectively. Despite differences in sedentary time by age, there were no significant differences in sedentary time by sex in children (boys: 367.2 ± 117.6 min day−1 vs. girls: 379.5 ± 114.4 min day−1) or adults (male: 520.1 ± 181.4 min day−1 vs. female: 514.1 ± 163.5 min day−1). Breakdowns of total sedentary time by country during the COVID-19 pandemic for children and adults are displayed in Table 3 and Table 4. Cautiously, geographical variations in sedentary time during COVID-19 are apparent in adults, with adults residing in Asian countries engaging in less sedentary time (350.7 ± 184.2 min day−1) compared to European (512.2 ± 225.3 min day−1), North American (515.0 ± 146.0 min day−1), and South American (530.0 ± 20.0 min day−1) adults.

Table 3.

Sedentary time of children during the COVID-19 pandemic by country.

Table 4.

Sedentary time of adults and older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic by country.

Data on specific sedentary behaviours was sparse, with the exception of daily screen time which was suggested to account for 57.2% of total sedentary time (i.e., 274.0 ± 90.1 min day−1) in adults. Similarly, screen time was the only specific sedentary behaviour examined consistently in children, accounting for 205.4 ± 23.2 min day−1, or 46.8% of total sedentary time. Of the studies that reported associations between changes in sedentary time and health outcomes, the most commonly measured health outcomes were quality of life [20,45,48,61,62,64,68,71,84,85], anxiety and depression [18,20,21,37,46,82] and global mental health [20,42,48,61,62,84,85], with one study measuring the likelihood of seizures in epileptic and otherwise healthy children [32]. The evidence suggests that increases in sedentary time resulting from the COVID-19 restrictions were weakly, but significantly, negatively correlated with quality of life (r2 = −0.05, p > 0.05; [20,45,48,61,62,64,68,71,84,85]), and global mental health (r2 = −0.10, p > 0.05; [20,42,48,61,62,84,85]) however it should be noted that not all studies reported significant associations [20]. Conversely, those with a greater sedentary time had a higher likelihood of depression and anxiety (odds ratio: 1.35–1.57; [18,20,21,37,46,82]), although this may depend on the type of sedentary behaviour engaged in [18]. Total daily screen time was significantly associated with the likelihood of a seizure in children, independent of prior seizure history (r2 = 0.52–0.57, p < 0.01; [32]).

4. Discussion

The aim of this meta-analysis was to explore the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated government restrictions on sedentary time and sedentary behaviour. A key finding was that sedentary time was substantially increased, irrespective of the restrictions imposed or population. More specifically, children increased their sedentary time the most during the pandemic, although their overall time spent sedentary was still lower than observed in adults. There were no significant sex differences in sedentary time across the pandemic irrespective of age. Finally, increases in sedentary time as a result of the pandemic were weakly, but significantly, related with QoL and mental health, with higher time spent sedentary associated with greater anxiety and depression.

4.1. Children’s Sedentary Time

The currently available evidence suggests that children increased their overall sedentary time by 159.5 min day−1 during the COVID-19 pandemic, although it is pertinent to note the large standard deviation (±142.6 min day−1). This therefore highlights the huge disparity in response in this population. Indeed, these results suggest that some children may have accrued similar sedentary time on weekdays during restrictions to during their normal school routines. Whilst it could be postulated that those exhibiting smaller absolute increases in sedentary time may have been characterised by a lower baseline time spent being sedentary and thus the relative increase was still similar, it is of concern to note that some children may have increased their sedentary time by more than five hours per day. Potential reasons for this large discrepancy in sedentary time may be disparities in access to gardens and green spaces during confinement, limiting opportunities to break-up prolonged sedentary time [31,87,88]. More specifically, Akpinar [89] reported that the distance between urban green spaces and the home was significantly correlated with children’s screen time, even after covarying for age and socioeconomic status [SES; [87,90]. Whilst the determinants of sedentary time and behaviour are multifaceted, SES is a critically important factor determining PA and sedentary time in children [90], with COVID-19 exacerbating pre-existing inequalities. Furthermore, other social factors, such as a low parental education level, children with overweight/obese parents [31], and children of parents with high anxiety regarding COVID-19 [37], were all correlates of an increased sedentary time. The finding that screen time accounted for ~47% of total sedentary time was expected given that the majority of countries worldwide have now adopted online learning methods [52].

Despite the apparent increase in sedentary time during the pandemic in children observed in the present meta-analysis, the total sedentary time determined in this review (383.9 ± 138.2 min day−1) was nonetheless in accord with [91,92], or lower than [13,93], the figures reported prior to the pandemic. This is likely to be predominantly due to a reliance on subjective recall measures during the pandemic [94]. More specifically, the reliability of recall measures, especially in children, is limited, with boys typically overestimating the amount of PA and sedentary time they perform [95]. Furthermore, children’s misrepresentation of time potentially exaggerates recall bias [95], and that the volume of sedentary time is only one component of a wider composition of daily movement behaviours which are critical for current and future health outcomes [1,91,96,97]. It is also noteworthy that the meta-analysis in children was conducted on only six studies that provided pre-post data, accounting for only 15.0% of the total review population [27,29,30,31,32,38]. Caution must therefore be taken when extrapolating the findings from this meta-analysis to the wider population.

Despite the wide discrepancy in both children’s absolute and increases in sedentary time, there were no sex differences in cumulative sedentary time, which may be considered to be unsurprising given that both boys and girls have been equally affected by lockdown measures. However, pre-COVID-19, it was consistently reported that girls were more sedentary than similarly aged boys [12,93,98,99]. This may therefore indicate that the pandemic had a greater impact on sedentary time in boys than girls. Indeed, despite accruing less overall sedentary time than girls, boys consistently reported an increased screen time [100], with lockdown restrictions likely exaggerating these observations which may explain the lack of sex difference. It is also pertinent to note that previous research has consistently reported that boys are more active during school hours than girls, indicating the social element of PA may be of greater importance to boys [101]. Consequently, the social confinement associated with COVID-19 restrictions may have had a greater impact on boy’s PA levels and subsequent sedentary time. The lack of sex difference may be attributable to different data collection methods between studies, and differences in questions asked, which have varying degrees of reliability [102].

Three studies examined the association of sedentary time with health outcomes in children with conflicting results [20,21,32]. More specifically, Kang et al. [20] reported no association between total sedentary time and perceived mood in 4898 Chinese adolescents (16.3 ± 1.3 years), whereas Lu et al. [21] reported those with a sitting time of ≥4 h day−1 had a greater risk of experiencing anxiety, depression and insomnia (OR: 1.35–1.87) in a similar sample of 953 Chinese adolescents (15.3 ± 0.5 years). These differences cannot be attributed to cultural, age or lockdown restrictions and may therefore be indicative of the protective role that the maintenance of PA has on mental health during times of adversity, although more data is needed to confirm this postulation. However, the discrepancy may also be due to differences in the measures of sedentary time used, with Kang et al. [20] reporting total sedentary time while Lu et al. [21] focused specifically on sitting time. Given that the influence of being sedentary on health outcomes is well evidenced to be dependent on specific type of sedentary behaviour [5,26,92,103], further inter-study comparisons are therefore precluded.

4.2. Adults and Older Adults

Overall, adults increased their sedentary time by 126.9 ± 42.2 min day−1, spending a cumulative 510.5 ± 167.9 min day−1 in sedentary behaviours, which was significantly higher than children (+ 127 min day−1). The reasons for this are not immediately clear and are likely multifaceted. One possible reason for the higher absolute sedentary time in adults compared to children could be due to their higher sedentary time pre-COVID possibly due to sedentary occupations [104]. Moreover, adults who adhered strictly to guidelines experienced an additional increase of 60 min day−1 in sedentary time during the pandemic than those who did not [44]. Furthermore, adults with higher levels of COVID-19 related anxiety were more likely to demonstrate a higher sedentary time compared to those with low anxiety [37]. Additionally, the lack of commute to work due to lockdown and homeworking requirements in most countries and the closure of sporting facilities (gyms, swimming pools etc) is likely to reduce PA opportunities to a greater extent in adults than children. Indeed, it is well accepted that adults complete PA in a structured, planned manner [8,105] and therefore COVID-19 is likely to have a bigger impact upon their PA and sedentary time levels. Taken together, this suggests that children and adults may experience different effects stemming from COVID-19 restrictions and therefore a one-size fits all approach to minimise the health detriments is unlikely to be effective for both populations. Similar to children, there were no sex differences in total sedentary time in adults suggesting men have been disproportionately affected by the effects of COVID-19 restrictions compared to women. Potential reasons for the lack of sex differences include women choosing to partake in physical activity closer to the home [106] which may have been less impacted and the greater proportion of men who regularly partake in team sport activities [107] which were suspended during the pandemic.

Older adults were the most sedentary group included within this systematic review and meta-analysis, with sedentary time totalling 586.3 ± 25.2 min day−1. However, they were also the least impacted by COVID-19, with their sedentary time only increasing by an average of 46.9 ± 22.0 min day−1. This may be due to their reduced likelihood of being in employment and lower tendency to be highly active prior to COVID-19 [107]. Similar to children, there were no significant sex differences in overall sedentary time, despite females engaging in more sedentary time pre-COVID-19 [4,6]. This may therefore similarly suggest that COVID-19 may have had more of an influence on males’ sedentary time than females’ but more evidence is needed to confirm this postulation.

The regional trends in this meta-analysis were discordant with previous research which reported that Asian adults were the most sedentary [108] and potentially indicate the effect of different lockdown strategies on sedentary time and behaviour. More specifically, China enforced strict, localised lockdowns in areas of infection, and lesser restrictions in areas of lower infection rates, as opposed to blanket national restrictions [109]. Whilst it could be speculated that including participants from non-lockdown regions potentially adds bias within the data, it also provides insights as to how COVID-19 may be managed whilst minimising the undesirable health consequences of lockdown conditions. However, it must be noted that there are a multitude of other factors that influence sedentary time and behaviour [5,110], therefore examining the specific influence of different governmental restrictions globally remains challenging.

Twelve studies examined the effect of sedentary time and behaviour on health-related outcomes in adults [18,45,46,48,61,62,64,68,71,82,84,85]. More specifically, five considered global mental health [18,48,61,84,85] and generally reported a negative association between sedentary time and global mental health, concordant with previous research [111]. However, Stieger et al. [62] reported that sedentary time was positively associated with perceived levels of stress but not overall mental health score, and therefore other lifestyle factors may also be important for the maintenance of mental health during lockdown. Other lifestyle factors noted within the current review include diet [45,51,71,79], physical activity [59,111] and minimising tobacco and alcohol consumption [48,58,79]. Similar relationships were observed regarding the effect of sedentary time on quality of life, [58,62,65,87], depression symptoms [33,82], and subjective well-being [52], highlighting the significant, and diverse, negative consequences of excessive sedentary time. Strategies need to be employed to encourage the breaking up of prolonged sedentary periods and the re-opening of sports facilities and green spaces needs to be prioritised when restrictions are eased for general health and well-being.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Whilst there are many strengths of this review, including the meta-analysis to quantify changes in sedentary time during the COVID-19 pandemic, the identification of inter-country differences, and the inclusion of both children and adults, there are some limitations which must be acknowledged. First, the global pandemic is still ongoing, with scientific knowledge in this area being updated weekly, which may impact the overall findings. Nevertheless, this review consolidates our current understanding and highlights areas which require further research. Secondly, the majority of studies did not comprehensively report the lockdown restrictions currently in place during the time of data collection, using phrases such as ‘lockdown’ or ‘home-stay’ requirements which were interpreted differently in almost every country [15]. Therefore, no evidence is available to assess the impact of specific lockdown restrictions on sedentary time and behaviours. Additionally, little information was able to be synthesised within this review on the effects of specific sedentary behaviours which are purported to have differing health effects [3,4,58]. Moreover, the reliance on subjective recall data, especially in children, has recognised limitations and questionable validity [102] and therefore the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted as an estimation only regarding the effect of COVID-19 on sedentary time in children, adults, and older adults. Finally, SES, a strong correlate of sedentary time, was not able to be controlled for within this meta-analysis due to a paucity of available data and needs considering in future work.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased sedentary time irrespective of lockdown conditions or population. Of importance, greater increases in time spent sedentary were suggested to be evident in both boys and men, suggesting that they have been disproportionally affected by lockdown restrictions. Moreover, increases in sedentary time as a result of COVID-19 restrictions were weakly, but significantly, correlated to poorer QoL, global mental health, depression, and likelihood of seizures. Therefore, as restrictions ease there should be a focus on reengaging everybody with PA and encouraging the breaking up of prolonged sedentary periods to improve both physical and mental well-being.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph182111286/s1. Search Terms, Table S1: Risk of Bias Table—Child studies, Table S2: Risk of bias and quality assessment for all studies included involving adults and older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., K.A.M. and M.A.M.; Literature searching and methodology, A.R.; formal analysis, A.R. with secondary assistance from R.L.K. and critical interpretation from K.A.M. and M.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, R.L.K., M.A.M., A.R., L.S., K.A.M., J.S. and R.T.; supervision, M.A.M. and K.A.M.; project administration, M.A.M. and K.A.M.; funding acquisition, M.A.M. and K.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was received from Sport Wales which enabled the appointment of the research assistant (first author) who conducted this review.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Saunders, T.J.; Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, M.S. Sedentary behaviour as an emerging risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases in children and youth. Can. J. Diabetes 2014, 38, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Väistö, J.; Haapala, E.; Viitasalo, A.; Schnurr, T.; Kilpeläinen, T.; Karjalainen, P.; Westgate, K.; Lakka, H.; Laaksonen, D.; Ekelund, U.; et al. Longitudinal associations of physical activity and sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, P.; Steptoe, A.; Liao, Y.; Hsueh, M.; Chen, L. A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all cause mortality in adults: A meta-regression analysis involving more than one million participants. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, K.; Howard, V.; Hutto, B.; Colabianchi, N.; Vena, J.; Safford, M.; Blair, S.; Hooker, S. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in U.S. Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A National Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitzmann, M.F.; Jochem, C.; Schmid, D. (Eds.) Sedentary Behaviour Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot, E.; Edwardson, C.; Achana, F.; Davies, M.; Gorley, T.; Gray, L.; Khunti, K.; Yates, T.; Biddle, S. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, N.; Healy, G.; Matthews, C.; Dunstan, D. Too much sitting: The population-health science of sedentary behaviour. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Brown, W.; Fagerland, M.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I. Physical activity attenuates the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality: A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than one million men and women. Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carson, V.; Tremblay, M.; Chaput, J.; McGregor, D.; Chastin, S. Compositional analyses of the associations between sedentary time, different intensities of physical activity, and cardiometaolic biomarkers among children and youth from the United States. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rideout, V.; Foehr, U.; Roberts, D. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds. Available online: https://www.kff.org/other/event/generation-m2-media-in-the-lives-of/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Leatherdale, S.; Ahmed, R. Screen-based sedentary behaviours among a nationally representative sample of youth: Are Canadian kids couch potatoes? Chronic Dis. Inj. Can. 2011, 31, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.; Dalene, K.; Kolle, E.; Northstone, K.; Møller, N.; Grøntved, A.; Wedderkopp, N.; Kriemler, S.; Page, A.; et al. Variations in accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time across Europe—Harmonized analyses of 47,497 children and adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Slapsinskaite, A.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Gui, C. Accelerometer-measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in Chinese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2020, 186, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, P.; Biddle, S.; Buman, M.; Chastin, S.; Ekelund, U.; Friedenreich, C.; Katzmarzyk, P.; Leitzmann, M.; Stamatakis, E.; van der Ploeg, H.; et al. New global guidelines on sedentary behaviour and health for adults: Broadening the behavioural targets. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 51; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, D.; Dale, B.; Stylianou, N.; Lowther, E.; Ahmed, M.; de la Torre Areanas, I. Coronavirus: The World in Lockdown in Maps and Charts. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Caputo, E.; Reichert, F. Studies of Physical Activity and COVID-19 during the Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Herring, M. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugbolue, U.; Duclos, M.; Urzeala, C.; Berthon, M.; Kulik, K.; Bota, A.; Thivel, D.; Bagheri, R.; Gu, Y.; Baker, J.; et al. An Assessment of the Novel COVISTRESS Questionnaire: COVID-19 Impact on Physical Activity, Sedentary Action and Psychological Emotion. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, B.; Zhu, W. Is Physical Activity Associated with Mental Health among Chinese Adolescents during Isolation in COVID-19 Pandemic? J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 11, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Chi, X.; Liang, K.; Chen, S.; Huang, L.; Guo, T.; Jiao, C.; Yu, Q.; Veronese, N.; Soares, F.; et al. Moving More and Sitting Less as Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors are Protective Factors for Insomnia, Depression, and Anxiety among Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available online: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2011).

- Janssen, I.; Clarke, A.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.; Giangregorio, L.; Kho, M.; Poitras, V.; Ross, R.; Saunders, T.; Ross-White, A.; et al. A systematic review of compositional data analysis studies examining associations between sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity with health outcomes in adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. = Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, S248–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, V.; Gray, C.; Janssen, X.; Aubert, S.; Carson, V.; Faulkner, G.; Goldfield, G.; Reilly, J.; Sampson, M.; Tremblay, M. Systematic review of the relationships between sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia, J.; Lawrence, S.; Brazendale, K.; Leahy, N.; Fukuda, D. Brief report: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 14, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciberras, E.; Patel, P.; Stokes, M.; Coghill, D.; Middeldorp, C.; Bellgrove, M.; Becker, S.; Efron, D.; Stringaris, A.; Faraone, S.; et al. Physical Health, Media Use, and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents with ADHD during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. J. Atten. Disord. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrobelli, A.; Pecoraro, L.; Ferruzzi, A.; Heo, M.; Faith, M.; Zoller, T.; Antoniazzi, F.; Piacentini, G.; Fearnbach, S.; Heymsfield, S. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lifestyle Behaviors in Children with Obesity Living in Verona, Italy: A Longitudinal Study. Obesity 2020, 28, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bueno, R.; López-Sánchez, G.; Casajús, J.; Calatayu, J.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Grabovac, I.; Tully, M.; Smith, L. Health-Related Behaviors among School-Aged Children and Adolescents during the Spanish COVID-19 Confinement. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, M.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Oses, M.; Arenaza, L.; Amasene, M.; Labayen, I. Changes in lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: A longitudinal analysis from the MUGI project. Pediatr. Obes. 2021, 16, e12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, F.; Merolla, E.; Solimeno, M.; de Leva, M.; Lenta, S.; Di Mita, O.; Bonadies, A.; Striano, P.; Tipo, V.; Varone, A. Is COVID-19 lockdown related to an increase of accesses for seizures in the emergency department? An observational analysis of a paediatric cohort in the Southern Italy. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 41, 3475–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Mukherjee, R.; Sen, D.; Sahu, S. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep behaviour and screen exposure time: An observational study among Indian school children. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyimaya, A.; Irmak, Y. Relationship between parenting practices and children’s screen time during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 56, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, S.; Sperandei, S.; Freebairn, L.; Conroy, E.; Jani, H.; Marjanovic, S.; Page, A. The Impact of Physical Distancing Policies during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health and Well-Being among Australian Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2020, 67, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, N.; Sadowski, A.; Laila, A.; Hruska, V.; Nixon, M.; Ma, D.; Haines, J.; On Behalf Of The Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.; Doyle-Baker, P.; Petersen, J.; Ghoneim, D. Parent anxiety and perceptions of their child’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Anedda, B.; Burchartz, A.; Eichsteller, A.; Kolb, S.; Nigg, C.; Niessner, C.; Oriwol, D.; Worth, A.; Woll, A. Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: A natural experiment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.; Do, B.; Wang, S. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, R.; Moore, S.; Gillespie, M.; Faulkner, G.; Vanderloo, L.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Rhodes, R.; Brussoni, M.; Tremblay, M. Healthy movement behaviours in children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the role of the neighbourhood environment. Health Place 2020, 65, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, R.; Pedro, M.; Delvecchio, E.; Espada, J.; Morales, A.; Mazzeschi, C.; Orgilés, M. Psychological Symptoms and Behavioral Changes in Children and Adolescents during the Early Phase of COVID-19 Quarantine in Three European Countries. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinner, C.; Matzka, M.; Leppich, R.; Kounev, S.; Holmberg, H.; Sperlich, B. The Impact of the German Strategy for Containment of Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 on Training Characteristics, Physical Activity and Sleep of Highly Trained Kayakers and Canoeists: A Retrospective Observational Study. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 579830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, D.; Pinto, A.; Goessler, K.; Nicoletti, C.; Sieczkowska, S.; Meireles, K.; Esteves, G.; Genario, R.; Oliveira Júnior, G.; Santo, M.; et al. Influence of Adherence to Social Distancing Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity Level in Post-bariatric Patients. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1372–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biviá-Roig, G.; La-Rosa, V.; Gómez-Tébar, M.; Serrano-Raya, L.; Amer-Cuenca, J.; Caruso, S.; Commodari, E.; Barrasa-Shaw, A.; Lisón, J. Analysis of the Impact of the Confinement Resulting from COVID-19 on the Lifestyle and Psychological Wellbeing of Spanish Pregnant Women: An Internet-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneck, A.; Silva, D.; Malta, D.; Souza-Júnior, P.; Azevedo, L.; Barros, M.; Szwarcwald, C. Physical inactivity and elevated TV-viewing reported changes during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with mental health: A survey with 43,995 Brazilian adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 140, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda-Babarro, A.; Arbillaga-Etxarri, A.; Gutiérrez-Santamaría, B.; Coca, A. Physical Activity Change during COVID-19 Confinement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheval, B.; Sivaramakrishnan, H.; Maltagliati, S.; Fessler, L.; Forestier, C.; Sarrazin, P.; Orsholits, D.; Chalabaev, A.; Sander, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colivicchi, F.; Di Fusco, S.; Magnanti, M.; Cipriani, M.; Imperoli, G. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic and Italian Lockdown Measures on Clinical Presentation and Management of Acute Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.; Ferracuti, S.; De Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Protano, C.; Valeriani, F.; Parisi, E.; Valerio, G.; Liguori, G.; et al. Sedentary Behaviors and Physical Activity of Italian Undergraduate Students during Lockdown at the Time of CoViD-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.; Zielinska, M.; Hamułka, J. Dietary and Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdowns among Polish Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey PLifeCOVID-19 Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, X.; Fleming, L.; Kirk, A.; Rollins, L.; Young, D.; Grealy, M.; MacDonald, B.; Flowers, P.; Williams, L. Changes in Physical Activity, Sitting and Sleep across the COVID-19 National Lockdown Period in Scotland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bueno, R.; Calatayud, J.; Casaña, J.; Casajús, J.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Andersen, L.; López-Sánchez, G. COVID-19 Confinement and Health Risk Behaviors in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, F.; Cenacchi, V.; Vegro, V.; Pavei, G. COVID-19 lockdown: Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in Italian medicine students. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon-López, D.; Bernardez-Vilaboa, R.; Fernandez-Balbuena, A.; Sillero-Quintana, M. The Influence of COVID-19 Isolation on Physical Activity Habits and Its Relationship with Convergence Insufficiency. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.; Duncan, M.; Clarke, N.; Myers, T.; Tallis, J. The influence of COVID-19 measures in the United Kingdom on physical activity levels, perceived physical function and mood in older adults: A survey-based observational study. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Larrad, A.; Mañas, A.; Labayen, I.; González-Gross, M.; Espin, A.; Aznar, S.; Serrano-Sánchez, J.A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; González-Lamuño, D.; Ara, I.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Confinement on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Spanish University Students: Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, B.; Haesebaert, F.; Zante, E.; Benyamina, A.; Haesebaert, J.; Franck, N. Global Changes and Factors of Increase in Caloric/Salty Food Intake, Screen Use, and Substance Use during the Early COVID-19 Containment Phase in the General Population in France: Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Onieva-Zafra, M.; Parra-Fernández, M.; Prado-Laguna, M.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle in University Students: Changes during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanudo, B.; Fennell, C.; Sanchez-Oliver, A. Objectively-assessed physical activity, sedentary behaviour, smart phone use, and sleep patterns pre-and during-COVID-19 quarantine in young adults from Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.; James, R.; Magistro, D.; Donaldson, D.; Healy, L.; Nevill, M.; Hennis, P. Mental health and movement behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 19, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Lewetz, D.; Swami, V. Emotional Well-Being under Conditions of Lockdown: An Experience Sampling Study in Austria during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 2703–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M.; Khabour, O.; Alzoubi, K. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Amid Confinement: The BKSQ-COVID-19 Project. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, B.; Chawla, S.; Singh, H.; Jain, R.; Arora, I. Is coronavirus lockdown taking a toll on mental health of medical students? A study using WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, W.; Ashkanani, F. Does COVID-19 change dietary habits and lifestyle behaviours in Kuwait: A community-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, C.; Osaili, T.; Mohamad, M.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.; Abu Jamous, D.; Magriplis, E.; Ali, H.; Al Sabbah, H.; Hasan, H.; et al. Eating Habits and Lifestyle during COVID-19 Lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, C.; Osaili, T.; Mohamad, M.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.; Zampelas, A.; Habib-Mourad, C.; Jamous, O.; Ali, H.; Al Sabbah, H.; et al. Assessment of eating habits and lifestyle during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic in the Middle East and North Africa region: A cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Li, P.; Moyle, W.; Weeks, B.; Jones, C. Physical Activity, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Stress among the Chinese Adult Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Song, Y.; Nassis, G.; Zhao, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Emotional Well-Being during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, M.; Bishwas, M.; Moonajilin, M.; Gozal, D. Physical inactivity and sedentary behaviors in the Bangladeshi population during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lei, S.; Le, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yao, W.; Gao, Z.; Cheng, S. Bidirectional Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns on Health Behaviors and Quality of Life among Chinese Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Guo, B.; Ao, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Jia, P. Obesity and activity patterns before and during COVID-19 lockdown among youths in China. Clin. Obes. 2020, 10, e12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, S.; Eskici, G. Evaluation of emotional (depression) and behavioural (nutritional, physical activity and sleep) status of Turkish adults during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Huang, W.; Sheridan, S.; Sit, C.; Chen, X.; Wong, S. COVID-19 Pandemic Brings a Sedentary Lifestyle in Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkley, J.; Lepp, A.; Glickman, E.; Farnell, G.; Beiting, J.; Wiet, R.; Dowdell, B. The Acute Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in University Students and Employees. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, C.; Herring, M.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Meyer, J. Working From Home and Job Loss Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated with Greater Time in Sedentary Behaviors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.; Herring, M.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Schuch, F.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Martin, J.; Caswell, S.; et al. Joint prevalence of physical activity and sitting time during COVID-19 among US adults in April 2020. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A.; Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Lee, J.; Sesker, A.; Strickhouser, J.; Sutin, A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour during COVID-19: Trajectory and Moderation by Personality. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A.; Jehn, A.; Stackhouse, M.; Denice, P.; Ramos, H. Changes in health behaviours during early COVID-19 and socio-demographic disparities: A cross-sectional analysis. Can. J. Public Health = Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2020, 111, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, R.; Macêdo, G.; Cabral, L.; Oliveira, G.; Vivas, A.; Fontes, E.; Elsangedy, H.; Costa, E. Initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in hypertensive older adults: An accelerometer-based analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 142, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malta, D.; Szwarcwald, C.; Barros, M.; Gomes, C.; Machado, Í.; Souza Júnior, P.; Romero, D.; Lima, M.; Damacena, G.; Pina, M.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in adult Brazilian lifestyles: A cross-sectional study, 2020. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude Rev. Sist. Unico Saude Bras. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneck, A.O.; da Silva, D.R.; Malta, D.C.; de Souza, P.R.B.; Azevedo, L.O.; Barros, M.B.D.; Szwarcwald, C.L. Lifestyle behaviors changes during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine among 6881 Brazilian adults with depression and 35,143 without depression. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 4151–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Olavarría, D.; Latorre-Román, P.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Delgado-Floody, P. Positive and Negative Changes in Food Habits, Physical Activity Patterns, and Weight Status during COVID-19 Confinement: Associated Factors in the Chilean Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, N.; Opuni, F.; Mends-Brew, E.; Mensah, S.; Mensah, H.; Quansah, F. Short-Term Changes in Behaviors Resulting from COVID-19-Related Social Isolation and Their Influences on Mental Health in Ghana. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneck, A.; Silva, D.; Malta, D.; Souza-Júnior, P.; Azevedo, L.; Barros, M.; Szwarcwald, C. Changes in the clustering of unhealthy movement behaviors during the COVID-19 quarantine and the association with mental health indicators among Brazilian adults. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, C.; Pombo, A.; Luz, C.; Rodrigues, L.; Cordovil, R. COVID-19 Social Isolation in Brazil: Effects on the Physical Activity Routine of Families with Children. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. Orgao Of. Soc. Pediatr. Sao Paulo 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Gibbons, R.; Larouche, R.; Sandseter, E.; Bienenstock, A.; Brussoni, M.; Chabot, G.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; Pickett, W.; et al. What Is the Relationship between Outdoor Time and Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Physical Fitness in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Love, R.; Adams, J.; Atkin, A.; van Sluijs, E. Socioeconomic and ethnic differences in children’s vigorous intensity physical activity: A cross-sectional analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akpinar, A. Urban green spaces for children: A cross-sectional study of associations with distance, physical activity, screen time, general health, and overweight status. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, T.; Tremblay, M.; Mathieu, M.; Henderson, M.; O’Loughlin, J.; Tremblay, A.; Chaput, J. Associations of sedentary behavior, sedentary bouts and breaks in sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk in children with a family history of obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egan, C.; Webster, C.; Beets, M.; Weaver, R.; Russ, L.; Michael, D.; Nesbitt, D.; Orendorff, K. Sedentary time and Behaviour during School: A systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Health Educ. 2019, 50, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Straker, L.; Mathiassen, S. Patterning of children’s sedentary time at and away from school. Obesity (Silver Spring Md.) 2013, 21, E131–E133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.; Hesketh, K.; Cliff, D.; Barnett, L.; Salmon, J.; Dollman, J.; Morgan, P.; Hills, A.; Hardy, L. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of sedentary behaviour measures used with children and adolescents. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2011, 12, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottevaere, C.; Huybrechts, I.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Sjostrom, M.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Hagstromer, M.; Widhalm, K.; Molnar, D.; Moreno, L.A.; et al. Comparison of the IPAQ-A and ActiGraph in relation to VO2 max among European adolescents: The HELENA study. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Leblanc, A.G.; Janssen, I.; Kho, M.E.; Hicks, A.; Murumets, K.; Colley, R.C.; Duggan, M. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines for children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, R.; Garriguet, D.; Janssen, I.; Wong, S.; Saunders, T.; Carson, V.; Tremblay, M. The association between accelerometer-measured patterns of sedentary time and health risk in children and youth: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekelund, U.; Luan, J.; Sherar, L.; Esliger, D.; Griew, P.; Cooper, A. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA 2012, 307, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carson, V.; Tremblay, M.; Chaput, J.; Chastin, S. Associations between Sleep Duration, Sedentary Time, Physical Activity, and Health Indicators among Canadian Children and Youth Using Compositional Analyses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S294–S302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prince, S.; Roberts, K.; Melvin, A.; Butler, G.; Thompson, W. Gender and education differences in sedentary behaviour in Canada: An analysis of national cross-sectional surveys. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, J.; Hakonen, H.; Syväoja, H.; Kulmala, J.; Kankaanpää, A.; Ekelund, U.; Tammelin, T. Changes in physical activity and sedentary time during adolescence: Gender differences during weekdays and weekend days. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hidding, L.; Chinapaw, M.; van Poppel, M.; Mokkink, L.; Altenburg, T. An Updated Systematic Review of Childhood Physical Activity Questionnaires. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2797–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallal, P.; Anderson, L.; Bull, F.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress. pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arigo, D.; Pasko, K.; Mogle, J. Daily relations between social perceptions and physical activity among college women. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balish, S.; Deaner, R.; Rainham, D.; Blanchard, C. Sex Differences in Sport Remain When Accounting for Countries’ Gender Inequality. Cross-Cult. Res. 2016, 50, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, J.L.; Eslinger, D.W. Accelerometer assessment of physical activity in active, healthy older adults. J. Ageing Phys. Act. 2009, 17, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burki, T. China’s successful control of COVID-19. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, D.; Ricci, C.; Leitzmann, M.F. Associations of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time with all-cause mortality in US adults: The NHANES study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamer, M.; Coombs, N.; Stamatakis, E. Associations between objectively assessed and self-reported sedentary time with mental health in adults: An analysis of data from the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, A.V.; Sciomer, S.; Cocchi, C.; Maffei, S.; Gallina, S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradidge, P.J.L.; Kruger, H.S. Physical activity, diet and quality of life during mandatory (COVID-19) quarantine following repatriation. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 2050313x20972508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).