Ostracism, Psychological Capital, Perceived Social Support and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Youths: A Moderated Mediation Model

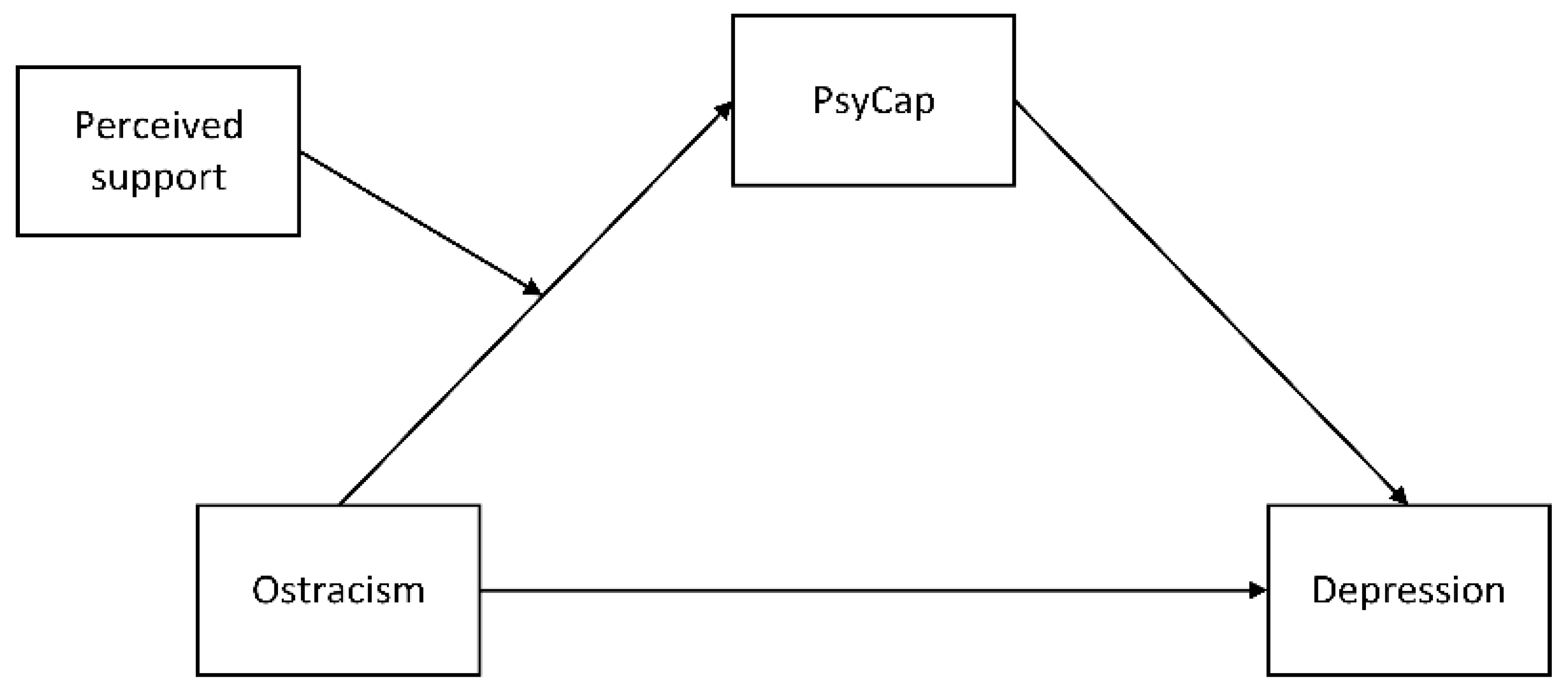

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Ostracism and Depression

1.2. Psychological Capital as a Mediator

1.3. Perceived Social Support as a Moderator

1.4. Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcomes

2.2.2. Predictor Variable

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses and Correlation Analyses

3.2. Test of Mediation

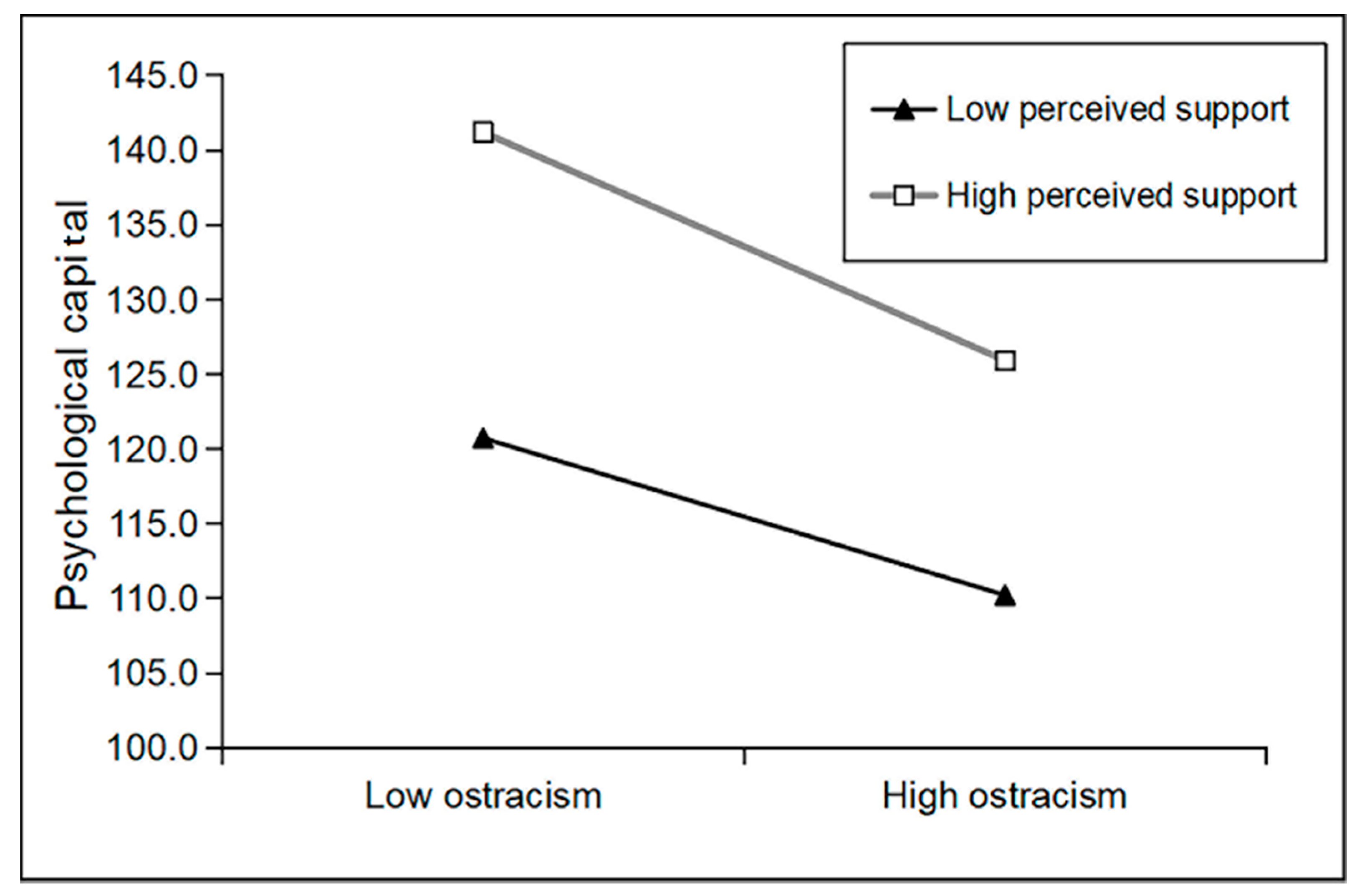

3.3. Test of Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital

4.2. The Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Koyanagi, A.; Chatterji, S.; Leonardi, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Koskinen, S.; Christine, J.R.-K.; Haro, M. The role of socio-economic status in depression: Results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health 2016, 16, e1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zou, R.; Xu, X.; Hong, X.; Yuan, J. Higher socioeconomic status predicts less risk of depression in adolescence: Serial mediating roles of social support and optimism. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, e1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y. The concept and manifestation of mental poverty and its interventions. J. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 42, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, D.; Jay, S.; McNamara, N.; Stevenson, C.; Muldoon, O.T. Perceived discrimination amongst young people in socio-economically disadvantaged communities: Parental support and community identity buffer (some) negative impacts of stigma. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 34, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 90, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Implications of Resilience Concepts for Scientific Understanding. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Ren, Z.; Hu, X.; Guo, Y. Why are undergraduates from lower-class families more likely to experience social anxiety?—The multiple mediating effects of psychosocial resources and rejection sensitivity. J. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 42, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.-m.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H.-y.; Deng, Y.; Shi, Y.-w.; Li, O. The poverty problem: Based on psychological perspective. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 25, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Kleinman, A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2003, 81, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.B.; Badcock, P.B.T. The social risk hypothesis of depressed mood: Evolutionary, psychosocial, and neurobiological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 887–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.-F.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Sun, X.-j.; Yu, F.; Xie, X.-C.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Lian, S.-L. Cyber-ostracism and its relation to depression among Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of optimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 123, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.-F.; Sun, X.-J.; Tian, Y.; Fan, C.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-K. Resilience moderates the relationship between ostracism and depression among Chinese adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentse, M.; Lindenberg, S.; Omvlee, A.; Ormel, J.; Veenstra, R. Rejection and acceptance across contexts: Parents and peers as risks and buffers for early adolescent psychopathology. The TRAILS Study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shochet, I.M.; Smith, C.L.; Furlong, M.J.; Homel, R. A prospective study investigating the impact of school belonging factors on negative affect in adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2011, 40, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Platt, B.; Kadosh, K.C.; Lau, J.Y.F. The Role of Peer Rejection in Adolescent Depression. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackhart, G.C.; Nelson, B.C.; Knowles, M.L.; Baumeister, R.F. Rejection Elicits Emotional Reactions but Neither Causes Immediate Distress nor Lowers Self-Esteem: A Meta-Analytic Review of 192 Studies on Social Exclusion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 269–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rubeis, J.; Lugo, R.G.; Witthoft, M.; Sutterlin, S.; Pawelzik, M.R.; Voegele, C. Rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability marker for depressive symptom deterioration in men. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lau, G.; Moulds, M.L.; Richardson, R. Ostracism: How Much It Hurts Depends on How You Remember It. Emotion 2009, 9, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of Resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haq, I.U. Workplace ostracism and job outcomes: Moderating effects of psychological capital. In Human Capital without Borders: Knowledge and Learning for Quality of Life; Proceedings of the Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference, Portorož, Slovenia, 25–27 June 2014; ToKnowPress: Bangkok, Tailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, J.; Ngo, H.-Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Jiao, W. Workplace ostracism and its negative outcomes. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Jalili, Y.; Khamseh, A. How does childhood predict adulthood psychological capital? Early maladaptive schemas and positive psychological capital. Ric. Psicol. 2020, 43, 789–816. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D.; Forgas, J.P.; Hippel, W.V. The Social Outcast: Ostracism, Social Exclusion, Rejection, and Bullying; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Calixte-Civil, P.F.; Brandon, T.H. The effect of acute interpersonal racial discrimination on smoking motivation and behavior among black smokers: An experimental study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O.D.; Goreis, A.; Glenk, L.M.; Kafka, J.X.; Beutl, L.; Kryspin-Exner, I.; Hlavacs, H.; Palme, R.; Felnhofer, A. Virtual and real-life ostracism and its impact on a subsequent acute stressor. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 228, e113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Song, L. The dampen effect of psychological capital on adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 40, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Sun, N.; Song, X. The efficacy of psychological capital intervention (PCI) for depression from the perspective of positive psychology: A pilot study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, e1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, P.S.; Saucier, D.A.; Hafner, E. Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, M.G.; Cohen, J.L.; Lucas, T.; Baltes, B.B. The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.J.; Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhang, Z. Psychological capital and employee performance: A latent growth modeling approach. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, Q.; Cao, X. Psychological capital: A new perspective for psychological health education management of public schools. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F.; Cai, Z.H.; Xu, Q.J.C.J.N.M.D. Evaluation analysis of self-rating depression disorder scale in 1340 people. Chin. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1986, 12, 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zung, W.W.K. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1965, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, L.; Dong, Y. Reliability and validity of the ostracism experience scale for adolescents in Chinese adolescence. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, R.; Carter-Sowell, A.; DeWall, C.N.; Adams, R.E.; Carboni, I. Validation of the Ostracism Experience Scale for Adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, L.P.; Wu, Y.S.; Yu, J.J.; Zhou, J. The influence of volunteers’ psychological capital: Mediating role of organizational commitment, and joint moderating effect of role identification and perceived social support. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, e673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Assink, M.; Cipriani, A.; Lin, K. Associations between rejection sensitivity and mental health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhard, M.A.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Wüstenberg, T.; Musil, R.; Barton, B.B.; Jobst, A.; Padberg, F. The vicious circle of social exclusion and psychopathology: A systematic review of experimental ostracism research in psychiatric disorders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 270, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, C.N.; Gilman, R.; Sharif, V.; Carboni, I.; Rice, K.G. Left out, sluggardly, and blue: Low self-control mediates the relationship between ostracism and depression. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2012, 53, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Zhou, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, W.; Mu, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, C.; et al. Dull to social acceptance rather than sensitivity to social ostracism in interpersonal interaction for depression: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence from Cyberball tasks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambron, M.J.; Acitelli, L.K.; Pettit, J.W. Explaining gender differences in depression: An interpersonal contingent self-esteem perspective. Sex Roles 2009, 61, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Hopwood, C.J. Sex differences in interpersonal sensitivities across acquaintances, friends, and romantic relationships. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 89, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, J. Mediating Roles of Rejection Sensitivity and Depression in the Relationship between Perceived Discrimination and Aggression among the Impoverished College Students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Model construction for precise psychological assistance for economically disadvantaged students: Serial mediating effects based on social support and emotion regulation. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2019, 06, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

| Varibles | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ostracism | 28.089 | 6.873 | |||

| 2. Psychological capital | 125.031 | 19.663 | −0.526 ** | ||

| 3. Perceived support | 65.735 | 12.384 | −0.436 ** | 0.584 ** | |

| 4. Depression | 39.232 | 8.128 | 0.623 ** | −0.581 ** | −0.383 ** |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Dependent Variable: Depression) | Model 2 (Dependent Variable: Psychological Capital) | Model 3 (Dependent Variable: Depression) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | 95% CI | B | SE | t | 95% CI | B | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.21 | 0.43 | −0.50 | [−1.04, 0.62] | −4.69 | 1.11 | −4.22 | [−6.86, −2.51] | −0.90 | 0.40 | −2.29 | [−1.68, −0.13] |

| Ostracism | 0.74 | 0.03 | 27.51 | [0.68, 0.79] | −1.53 | 0.07 | −21.85 | [−1.66, −1.39] | 0.51 | 0.03 | 17.49 | [0.45, 0.57] |

| Psychological capital | −0.15 | 0.01 | −14.50 | [−0.17, −0.13] | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| F | 381.89 | 242.07 | 368.98 | |||||||||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Dependent Variable: Depression) | Model 2 (Dependent Variable: Psychological Capital) | Model 3 (Dependent Variable: Depression) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | 95% CI | B | SE | t | 95% CI | B | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.12 | 0.42 | −0.28 | [−0.94, 0.70] | −5.23 | 0.98 | −5.35 | [−7.15, −3.31] | −0.90 | 0.40 | −2.29 | [−1.68, −0.13] |

| Ostracism | 0.65 | 0.03 | 21.74 | [0.59, 0.71] | −0.94 | 0.07 | −13.47 | [−1.07, −0.80] | 0.51 | 0.03 | 17.49 | [0.45, 0.57] |

| Perceived support | −0.10 | 0.02 | −6.12 | [−0.14, −0.07] | 0.73 | 0.04 | 18.64 | [0.65, 0.80] | ||||

| Ostracism × Perceived support | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.92 | [0.001, 0.01] | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.95 | [−0.02, −0.01] | ||||

| Psychological capital | −0.15 | 0.01 | −14.50 | [−0.17, −0.13] | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| F | 206.70 | 243.98 | 368.98 | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Hazer-Rau, D.; Li, P.; Ji, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, T. Ostracism, Psychological Capital, Perceived Social Support and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Youths: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111282

Yu X, Zhang L, Lin Z, Zhou Z, Hazer-Rau D, Li P, Ji W, Zhang H, Wu T. Ostracism, Psychological Capital, Perceived Social Support and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Youths: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111282

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xianglian, Lin Zhang, Zihong Lin, Zongkui Zhou, Dilana Hazer-Rau, Pinlin Li, Wenlong Ji, Hanbing Zhang, and Tong Wu. 2021. "Ostracism, Psychological Capital, Perceived Social Support and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Youths: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111282

APA StyleYu, X., Zhang, L., Lin, Z., Zhou, Z., Hazer-Rau, D., Li, P., Ji, W., Zhang, H., & Wu, T. (2021). Ostracism, Psychological Capital, Perceived Social Support and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Youths: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111282