Threats to and Opportunities for Low-Income Homeownership, Housing Stability, and Health: Protocol for the Detroit 2017 Make-It-Home Evaluation Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Make It Home Program

Study Design and Sample

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Surveys

2.5. Additional Measures of House Condition and Neighborhood Environment

2.6. Property Data

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethics, Funding and Dissemination

3. Baseline Results

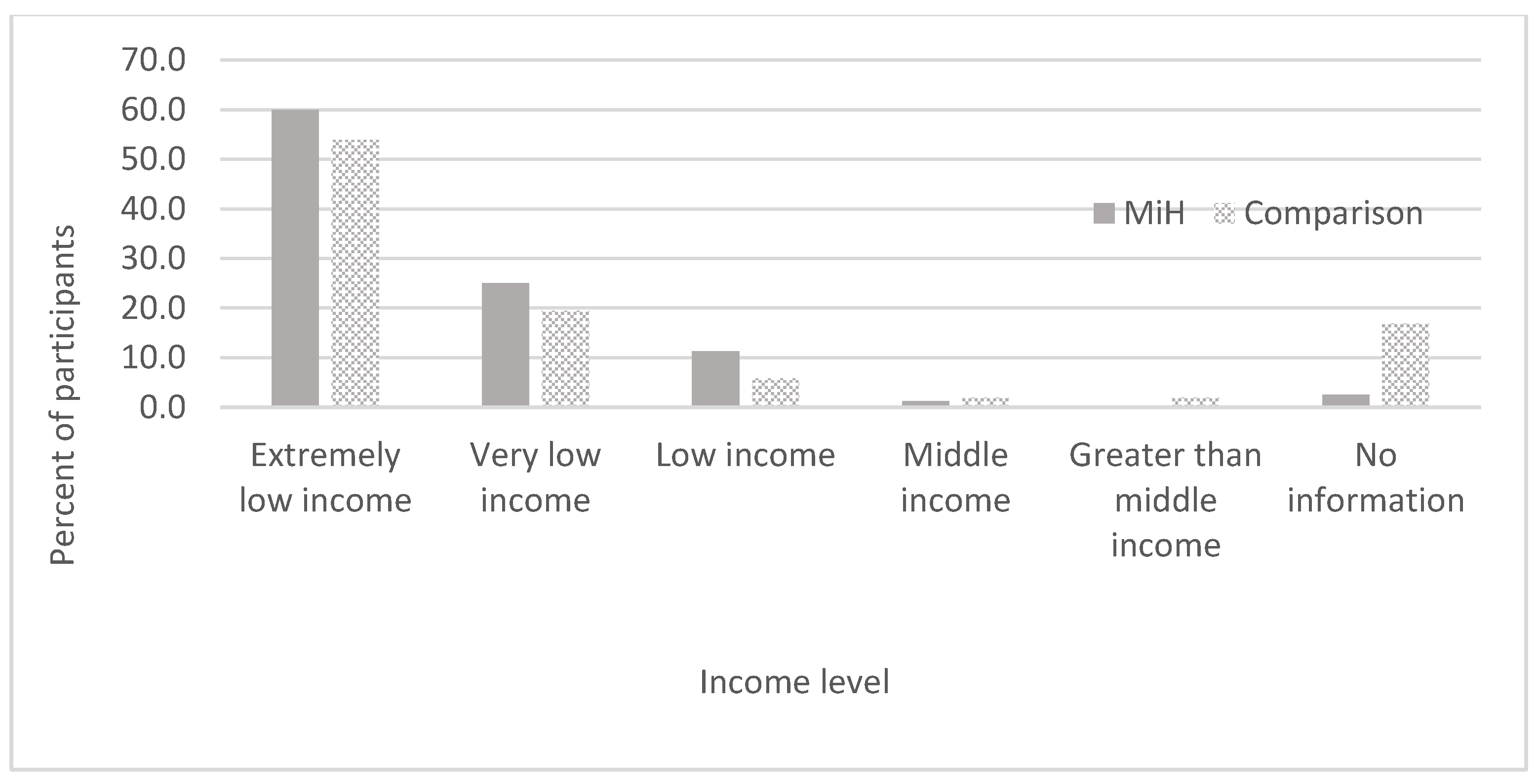

Characteristics of the MiH and Comparison Group at Baseline

4. Discussion

Strengths, Challenges and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burgard, S.A.; Seefeldt, K.S.; Zelner, S. Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R.; Hayes, M.V. Social inequality, population health, and housing: A study of two Vancouver neighborhoods. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, A.; Macintyre, S. Does housing tenure predict health in the UK because it exposes people to different levels of housing related hazards in the home or its surroundings? Health Place 1998, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M.; Van Zandt, S.; McCarthy, G. Home Ownership and Access to Opportunity. Hous. Stud. 2002, 17, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J.; Boyle, M.H. Home ownership, mortgages and psychological distress. Hous. Stud. 2004, 19, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saegert, S.; Fields, D.; Libman, K. Mortgage foreclosure and health disparities: Serial displacement as asset extraction in African American populations. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2011, 88, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Eisenberg, A.K.; Schulz, A.J. Chapter 5: Housing. In Urban Health; Galea, S., Ettman, C.K., Vlahov, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.J.; Lowe, T.S. Homebuyer Neighborhood Attainment in Black and White: Housing Outcomes during the Housing Boom and Bust. Soc. Forces 2015, 93, 1481–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flippen, C. Unequal Returns to Housing Investments? A Study of Real Housing Appreciation among Black, White, and Hispanic Households. Soc. Forces 2004, 82, 1523–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herbert, C.E.; McCue, D.T.; Sanchez-Moyano, R. Is Homeownership Still an Effective Means of Building Wealth for Low-Income and Minority Households? (Was It Ever?); Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, P.; Ferreira, F.; Ross, S.L. The Vulnerability of Minority Homeowners in the Housing Boom and Bust. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2016, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayer, C.J.; Pence, K. Subprime Mortgages: What, Where, and to Whom? [Internet]; (Working Paper Series). Report No.: 14083; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w14083 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Arcaya, M.; Glymour, M.M.; Chakrabarti, P.; Christakis, N.A.; Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V. Effects of Proximate Foreclosed Properties on Individuals’ Systolic Blood Pressure in Massachusetts, 1987–2008. Circulation 2014, 129, 2262–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Currie, J.; Tekin, E. Is There a Link Between Foreclosure and Health? [Internet]; (Working Paper Series). Report No.: 17310; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w17310 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Schootman, M.; Deshpande, A.D.; Pruitt, S.L.; Jeffe, D.B. Neighborhood foreclosures and self-rated health among breast cancer survivors. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2012, 21, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keene, D.E.; Lynch, J.F.; Baker, A.C. Fragile health and fragile wealth: Mortgage strain among African American homeowners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 118, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C.E.; Belsky, E.S. The Homeownership Experience of Low-Income and Minority Households: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. Cityscape 2008, 10, 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandt, S.; Rohe, W.M. The sustainability of low-income homeownership: The incidence of unexpected costs and needed repairs among low-income home buyers. Hous. Policy Debate 2011, 21, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A.; Wakayama, C.; Cooney, P. Reinforcing Homeownership through Home Repair: Evaluation of the Make It Home Repair Program [Internet]. Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan. February 2021. Available online: https://poverty.umich.edu/files/2021/02/PovertySolutions-Make-It-Home-Repair-Program-Feb2021-final.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Pollack, C.E.; Lynch, J. Health status of people undergoing foreclosure in the Philadelphia region. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.; Egelhof, R.; Hoke, M. Get Sick, Get Out: The Medical Causes of Home Mortgage Foreclosures. Health Matrix 2008, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cutshaw, C.A.; Woolhandler, S.; Himmelstein, D.U.; Robertson, C. Medical Causes and Consequences of Home Foreclosures. Int. J. Health Serv. Plan. Adm. Eval. 2016, 46, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Houle, J.N.; Keene, D.E. Getting sick and falling behind: Health and the risk of mortgage default and home foreclosure. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shlay, A.B. Low-income Homeownership: American Dream or Delusion? Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chisholm, E.; Keall, M.; Bennett, J.; Marshall, A.; Telfar-Barnard, L.; Thornley, L.; Howden-Chapman, P. Why don’t owners improve their homes? Results from a survey following a housing warrant-of-fitness assessment for health and safety. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2019, 43, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandel, M.; Desmond, M. Investing in Housing for Health Improves Both Mission and Margin. JAMA 2017, 318, 2291–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlow, D.; Smith, S.J.; Mallinson, S. Housing for Health: The Role of Owner Occupation. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J. Health status and the housing system. Soc. Sci. Med. 1990, 31, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates for Detroit, Table B25003B [Internet]; 2019. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=&t=Black%20or%20African%20American%3AHousing&g=1600000US2622000&y=2019&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B25003B (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates for Detroit, Table DP04 [Internet]; 2019. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=&t=Housing&g=1600000US2622000&y=2019&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP04 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 1-Year Estaimates for Detroit, Table B25002 [Internet]; 2017. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B25002&g=1600000US2622000&tid=ACSDT1Y2017.B25002 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Akers, J.; Seymour, E. Instrumental exploitation: Predatory property relations at city’s end. Geoforum 2018, 91, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Seymour, E.; Dewar, M.; Thomas, J.M. Saving Strong Neighborhoods From the Destruction of Mortgage Foreclosures: The Impact of Community-Based Efforts in Detroit, Michigan. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan Legislature—Section 211.78m [Internet]. Available online: http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(ub1ksvci0s3v25n0fziqbdjt))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectname=mcl-211-78m (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Aurand, A.; Emmanuel, D.; Threet, D.; Rafi, I.; Yentel, D. The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes [Internet]; National Low Income Housing Coalition: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://reports.nlihc.org/gap (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The State of the Nation’s Housing 2021 [Internet]; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/state-nations-housing-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Michigan State Housing Development Authority. 04/14/2017 Income and Rent Limits [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mshda/mshda_crh_il_67_income_limits_041417_558290_7.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. FY 2021 Income Limits Summary [Internet]. FY 2021 Income Limits Documentation System. 2021. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il/il2017/2017summary.odn (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- University of Michigan. Detroit Metro Area Communities Study—MorningSide Survey [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://poverty.umich.edu/files/2018/02/dmacs-morningside-su17-topline.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Narducci, C.; Mireles, A.; Comey, J. Astoria Houses Neighborhood Survey for Zone 126 Promise Neighborhood, 2012—Summary of Survey Findings—Astoria Houses [Internet]. 2012. Available online: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/26296/412717-Astoria-Houses-Neighborhood-Survey-for-Zone--Promise-Neighborhood-.PDF (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Earls, F.J.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Sampson, R.J. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Community Survey, 1994–1995 [Internet]; ICPSR: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; Available online: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/studies/2766 (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Bureau UC. American Housing Survey (AHS) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Holmes, T.H.; Rahe, R.H. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1967, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Rigolon, A.; Hadavi, S.; Stewart, W.P. Beyond proximity: Extending the “greening hypothesis” in the context of vacant lot stewardship. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.; Lester, T.W. Does Local Ownership of Vacant Land Reduce Crime? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2021, 87, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonevski, B.; Randell, M.; Paul, C.; Chapman, K.; Twyman, L.; Bryant, J.; Hughes, C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaghaghi, A.; Bhopal, R.S.; Sheikh, A. Approaches to Recruiting ‘Hard-To-Reach’ Populations into Research: A Review of the Literature. Health Promot. Perspect. 2011, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipanah, R. Housing as a Determinant of COVID-19 Inequities. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, A.J.; Mehdipanah, R.; Chatters, L.M.; Reyes, A.G.; Neblett, E.W.; Israel, B.A. Moving Health Education and Behavior Upstream: Lessons From COVID-19 for Addressing Structural Drivers of Health Inequities. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, A.; Mehdipanah, R.; Dewar, M. ‘It’s like they make it difficult for you on purpose’: Barriers to property tax relief and foreclosure prevention in Detroit, Michigan. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 1415–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MiH (N = 49) | Comparison (N = 39) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (mean) | 46.6 | 49.9 | |

| p value | 0.236 | ||

| Women (%) | 69.4 | 59.0 | |

| Men | 30.6 | 41.0 | |

| p value | 0.310 | ||

| African American (%) | 93.8 | 92.1 | |

| White | 0 | 5.3 | |

| Other | 6.1 | 2.6 | |

| p value | 0.207 | ||

| Employed (%) | 55.1 | 46.2 | |

| Unemployed | 22.5 | 17.9 | |

| Unable to work | 20.4 | 25.6 | |

| Retired | 2.0 | 10.3 | |

| p value | 0.334 | ||

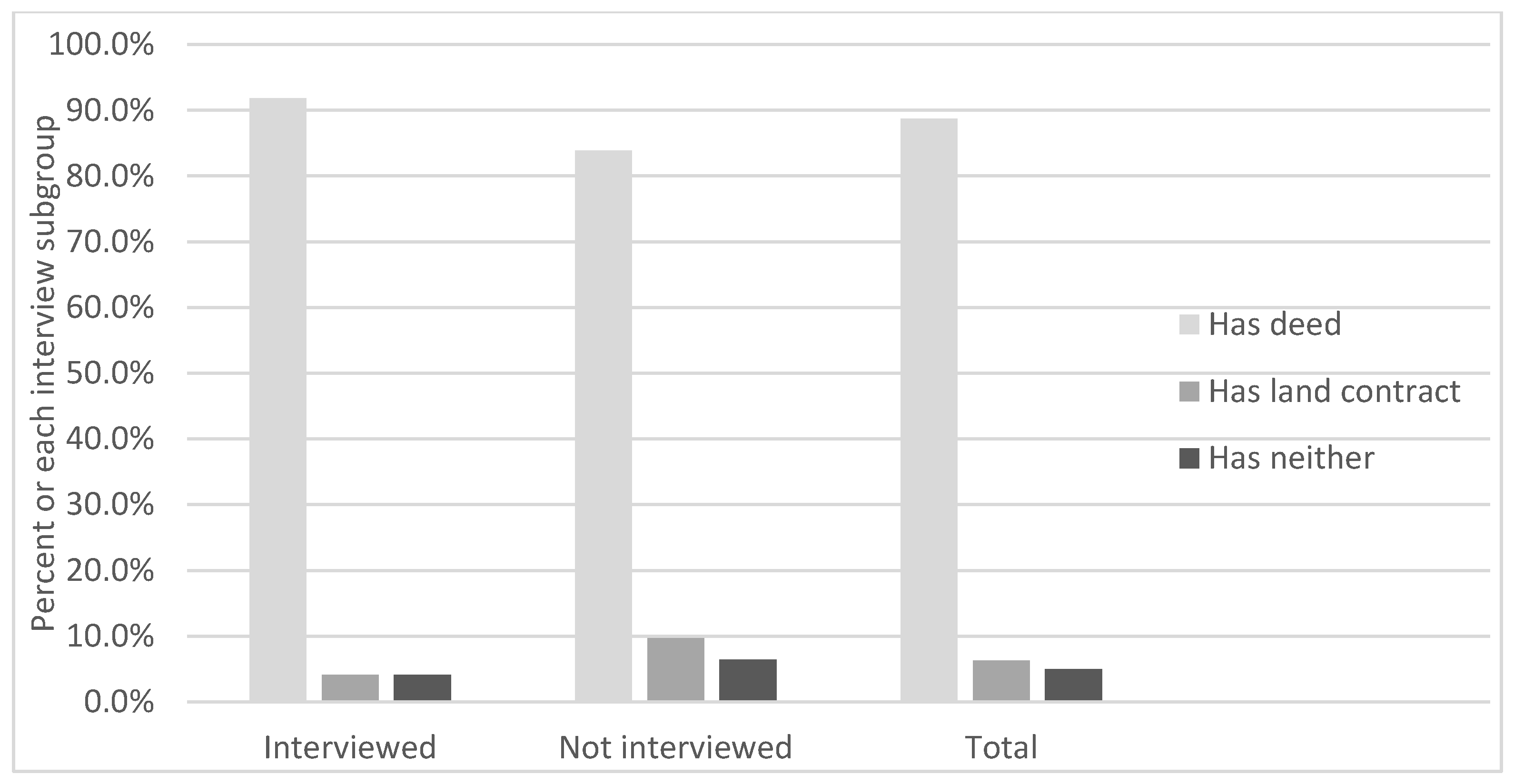

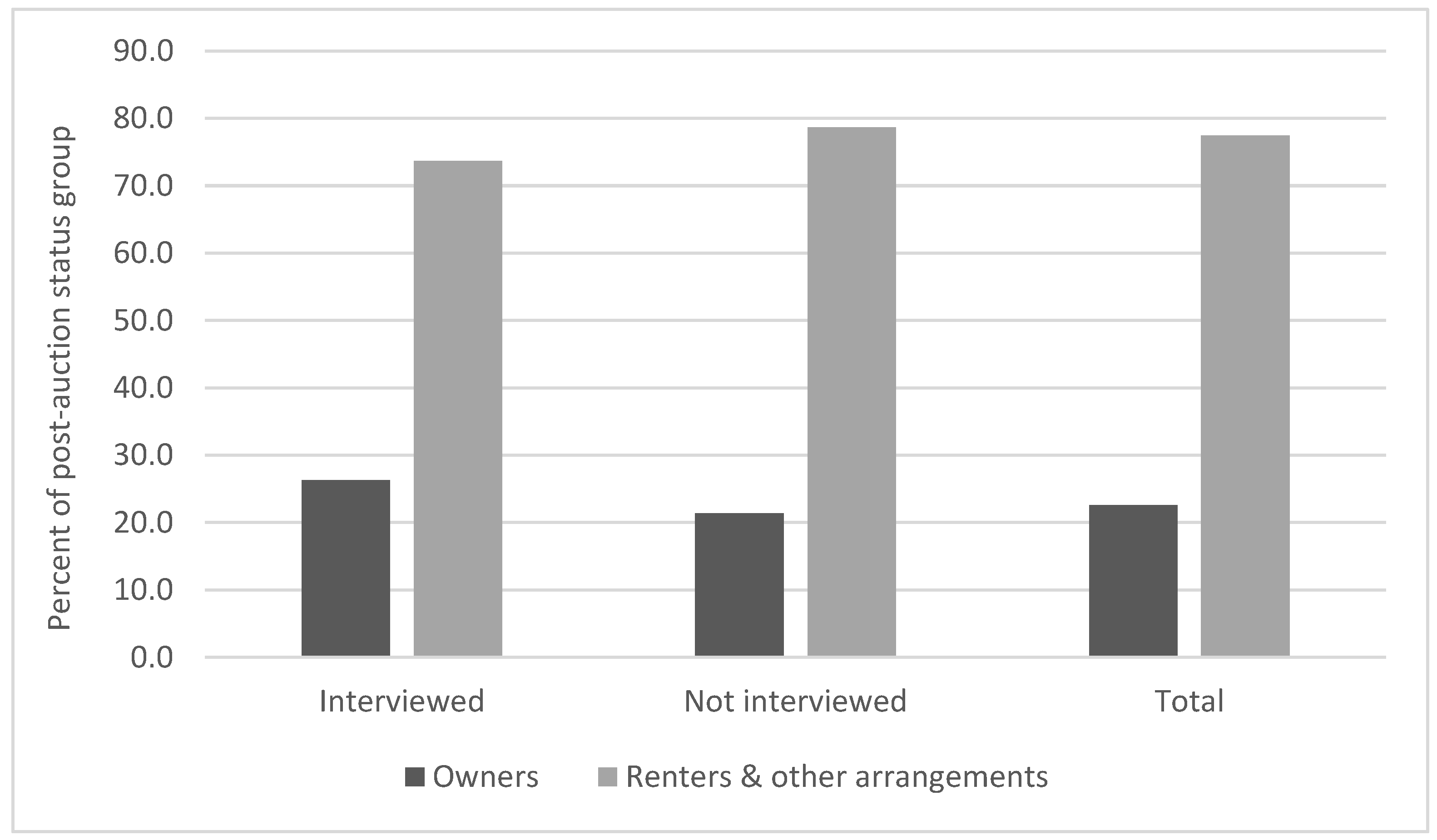

| Housing and Housing Instability Characteristics | |||

| Owner with deed (%) | 95.9 | 33.3 | |

| Owner in process | 4.1 | 0 | |

| Renter | 0 | 38.5 | |

| Other arrangement | 0 | 28.2 | |

| p value | 0.000 | ||

| Living in tax foreclosed home (%) | 100.0 | 46.2 | |

| Living elsewhere | 0 | 53.9 | |

| p value | 0.000 | ||

| Months in current home (mean) | 104.7 | 90.5 | |

| p value | 0.650 | ||

| Housing satisfaction (%) | |||

| Very satisfied | 6.1 | 12.8 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 46.9 | 25.6 | |

| Neutral | 24.5 | 25.6 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 20.5 | 15.4 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 2.0 | 20.5 | |

| p value | 0.024 | ||

| Neighborhood satisfaction (%) | |||

| Very satisfied | 16.3 | 20.5 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 44.9 | 25.6 | |

| Neutral | 22.5 | 28.2 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 12.2 | 12.8 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 4.1 | 12.8 | |

| p value | 0.308 | ||

| Ability to pay monthly housing bills (%) | |||

| Very easy | 6.1 | 5.1 | |

| Somewhat easy | 18.4 | 12.8 | |

| Neutral | 20.4 | 30.8 | |

| Somewhat difficult | 40.8 | 28.2 | |

| Very difficult | 14.3 | 23.1 | |

| p value | 0.510 | ||

| Worry about being forced out of home (%) | |||

| Strongly agree | 6.8 | 12.8 | |

| Agree | 9.1 | 12.8 | |

| Neutral | 6.8 | 23.1 | |

| Disagree | 31.8 | 48.7 | |

| Strong disagree | 45.5 | 0 | |

| No answer | 0 | 2.6 | |

| p value | 0.000 | ||

| Health outcomes | |||

| Good self-rated health (%) | 69.4 | 58.9 | |

| Poor self-rated health | 30.6 | 41.1 | |

| p value | 0.310 | ||

| No chronic conditions (%) | 18.4 | 12.8 | |

| One or more chronic conditions | 81.6 | 87.2 | |

| p value | 0.480 | ||

| Has health insurance (%) | 97.9 | 94.9 | |

| No health insurance | 2.1 | 5.1 | |

| p value | 0.428 | ||

| One or more life event (%) | 85.7 | 87.2 | |

| No life event | 14.3 | 12.8 | |

| p value | 0.842 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehdipanah, R.; Dewar, M.; Eisenberg, A. Threats to and Opportunities for Low-Income Homeownership, Housing Stability, and Health: Protocol for the Detroit 2017 Make-It-Home Evaluation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111230

Mehdipanah R, Dewar M, Eisenberg A. Threats to and Opportunities for Low-Income Homeownership, Housing Stability, and Health: Protocol for the Detroit 2017 Make-It-Home Evaluation Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111230

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehdipanah, Roshanak, Margaret Dewar, and Alexa Eisenberg. 2021. "Threats to and Opportunities for Low-Income Homeownership, Housing Stability, and Health: Protocol for the Detroit 2017 Make-It-Home Evaluation Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111230

APA StyleMehdipanah, R., Dewar, M., & Eisenberg, A. (2021). Threats to and Opportunities for Low-Income Homeownership, Housing Stability, and Health: Protocol for the Detroit 2017 Make-It-Home Evaluation Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111230