Intervention Programs to Promote the Quality of Caregiver–Child Interactions in Childcare: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

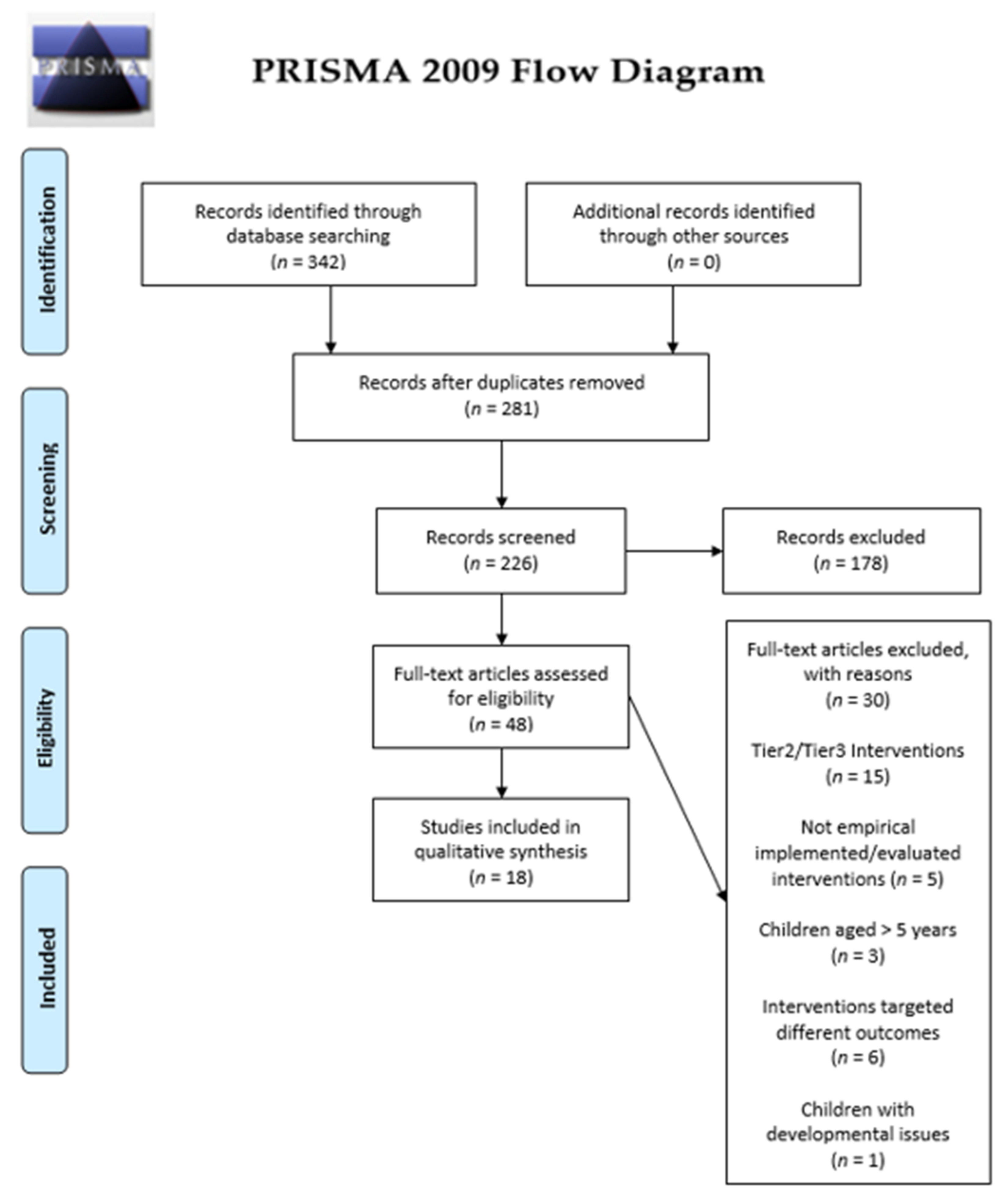

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

| Authors (Year), Country | Type of School | No. of Schools | No. Classes | Teachers/Caregivers | Children | Te.-Ch. Ratio | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Sex | Age (Mean) | Education (Degree or Higher) | Years of Experience (Mean) | No. | No. Per Class (Mean) | Sex | Age (Mean) | SES Background | |||||

| Baker-Henningham et al. (2009), Jamaica [21] | Preschool | 5 | 27 IG = 15 CG = 12 | 27 IG = 15 CG = 12 | - | - | 24 | IG = 12 CG = 14 | - | 21 | - | - | Heterogeneous | 1:21 |

| Biringen et al. (2012), USA [22] | Childcare | 21 | - | 57 Te.-Ch. pairs IG = 33 CG = 24 | - | 32 | IG = 4; CG = 5 | - | 57 | - | F 40% | IG = 17 mo.; CG = 23 mo. | - | 1:1 |

| Driscoll et al. (2011), USA [23] | Preschool | - | - | 252 Con.G.= 90; WebG. =96; CG= 66 | - | - | 83 | 14 | 1064 Con.G. 327; WebG. 278; CG 414 | 14 (enrolled 4 per class.) | F 50.8% | 4 y | Low SES (at-risk children) | 1:1 |

| Early et al., (2017), USA [6] | Preschool | 336 | - | 486 MMCI = 175; MTP = 151; CG = 160 | - | - | 91.3% | 6 | - | 19 | - | 4 y | Heterogeneous | 1:9 |

| Fabiano et al. (2013), USA [24] | Preschool | 27 | - | 88 W = 48; I = 40 | F 97% | 38 | 34 | 8 | - | 23 | - | 4 y | Low SES (Head Start) | 1:23 |

| Fawley et al. (2020), USA [25] | Preschool | 1 | 2 | 5 Cl. A = 3; Cl. B = 2 | F | - | - | - | 39 | Cl. A = 19; Cl. B = 20 | Cl.A 10M, 9F; Cl. B 12M, 8F; | Cl.A = 4.9 y Cl.B= 5 y | Heterogeneous | Cl. A = 3:19 Cl. B = 2:20 |

| Fukkink et al. (2010), the Netherlands [26] | Childcare | 2 | - | 95 IG = 52 CG = 43 | - | 28 | - | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 1:5–7 |

| Garbacz et al. (2014), USA [27] | Childcare | 1 | 4 | 12 | F | 43 | 41% | 11 | 51 | - | F 56% | 2–3 y | Heterogeneous | - |

| Garner et al. (2019), USA [28] | Preschool | 3 | 8 CrC = 5 RC = 3 | 12 | F | - | - | CrC ≤ 1 RC = 2–5 | 117 | - | F 64 | 4–5 y | Heterogeneous | - |

| Gray (2015), USA [29] | Childcare (Home-based) | - | - | 51 IG = 34 CG = 17 | IG: F = 33 | 44 | 24% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Groeneveld et al. (2011), the Netherlands [30] | Childcare (Home-based) | 23 | - | 49 IG = 24 CG = 25 (only caregiver scoring low on sensitivity) | - | IG = 43; CG = 40 | - | - | - | IG = 7 per center CG = 7 per center | - | <4 y | Heterogeneous | - |

| Groeneveld et al. (2016) the Netherlands [4] | Childcare (Home-based) | 23 | - | 47 IG = 23 CG = 24 (only caregiver scoring low on sensitivity) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | IG = 27 mo. CG = 25 mo. | Heterogeneous | - |

| Helmerhost et al. (2017), the Netherlands [8] | Childcare | 33 | 68 IG = 35 CG = 33 | 139 | F | 32 | 7% | 8 | - | 10 | - | 0–4 y | Heterogeneous | 1:5 |

| Jilink et al. (2018), the Netherlands [31] | Preschool | 22 | - | 72 ECE = 17 VIG = 16 ECE + VIG = 18 CG = 21 | F 71 | 46 | 6% | 14 | - | - | - | - | Heterogeneous | 1:4 |

| Lyon et al. (2009), USA [32] | Preschool | - | 4 | 12 | F | 37 | 4 | 8 | 78 | 19–21 | 3–5 y | Low SES (at-risk children) | - | |

| Moreno et al. (2015), USA [33] | Childcare (Center + Home-based) | - | - | 180 EQ = 114 CC = 30; CG = 36 | - | EQ = 34 CC = 41 CG = 43 | - | EQ = 4 CC = 9 CG = 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Werner et al., (2018), the Netherlands [5] | Childcare | 64 | IG = 4 per center CG = 3 per center | 64 IG = 34 CG = 30 | - | IG = 32 CG = 31 | IG = 14% CG = 12% | IG = 4 CG = 4 | IG = 66 per center; CG = 61 per center | 10 | - | 0–4 y | Low SES | 1:4 |

| Zan and Ritter (2014), USA [34] | Preschool | 4 | 30 | 60 IG = 38 CG = 22 | IG:F = 37 CG:F = 22 | IG = 39 CG = 22 | IG = 17 CG = 7 | IG = 10 CG = 9 | - | - | - | - | Low SES (Head Start) | - |

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

| Authors (Year), Country | Name of the Program | Validate Program | Focus of the Program | In Person/Web-Based | Group Training | Individual Training | Usage of Videos | Follow-Up Activities | Control Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | CO | IS | Yes/No (Main Activities) | Duration | Yes/No (Main Activities) | Duration | Yes/No (Video Type) | Yes/No (Activities) | Yes/No (Activities) | ||||

| Baker-Henningham et al. (2009), Jamaica [21] | The Incredible Years Teacher Training program | yes | yes | yes | no | In person | Yes (Psycho-education, role-playing, discussions (applying skills and concepts to their own situations), video) | 7 d, once a mo. (over 6 mo.) | Yes (Discuss challenging with the program implementation and potential solutions) | 1 h once a mo. | Yes (Video-modeling) | no | Yes (Same Te. resources + experts visit bimonthly) |

| Biringen et al. (2012), USA [22] | EA-based Intervention in Project Secure Child in Childcare | no | yes | no | no | In person | Yes (Psycho-education, handouts) | 2–1 h sessions | Yes (Expert provide written feedbacks on areas of strength and/or of need of improvement) | 3–4 visits over 2–3 mo. | Yes (Watch the pretest video with the coach with opportunity to narrate how to improve interactions) | no | Yes (no int.) |

| Driscoll et al. (2011), USA [23] | Banking Time in MyTeachingPartner Project | yes | yes | no | no | Web-based | no | - | Yes Con.G = materials (books, activities) to implement int. in class. + access website (resources to promote high-quality teaching and te.-ch. relationship); + teaching consultant WebG. = materials + access to the MTP website. | Con.G. = Not specified duration for indivdual training on web; teaching consultant every 2 wk. Web G.: Not specified duration for indivdual training on web | Yes (Video-modeling) | no | Yes (Materials + access to a limited portion of the MTP website) |

| Early et al., (2017), USA [6] | Making the most of classroom interactions (MMCI) + My teaching partner (MTP) | yes | yes | yes | yes | MMCI = In person MTP = Remote training | MMCI = yes (Psycho-education, discussions, print resources, online library of videos demonstrating best practice) MTP = no | MMCI = 10–2.5 h workshops in 5 d across 5 mo. | MMCI: no MTP: yes (online library of video clips demonstrating best practice + video-feedback and discussion on Te. Interactions with Ch.) | As many feedback-cycles as possible | Yes MMCI = video-modeling MTP = Remote Video-feedback | no | Yes 51 = same online library of video of MMCI and MTP; 109 = 15 h basic professional development course |

| Fabiano et al. (2013), USA [24] | Professional development in effective classroom management using positive behavioral supports | no | no | yes | no | In person | W = yes (Psycho-education, didactic presentations, discussions) I = yes (Psycho-education, didactic presentations, discussions + experiential training) | W = 6-h I = 6-h + 4 d experiential training | W = no I = yes (feedback session on Te.’s use of techniques) | I = after each practice period | no | Yes I&W = behavioural consultant on class. Observation | no |

| Fawley et al. (2020), USA [25] | Teacher–Child interaction Training-Universal (TCIT-U) | yes | yes | yes | no | In person | Yes (Psycho-education, discussions, practice worksheets, behaviour-coding, role-playing, videos) | 4 h | Yes Consultation: with the psychology Te- reviewed concepts, give and receive feedback and select a target behav. For coaching session; In class. coaching: in-vivo feedback with “bug-in-the-ear” technology” during class. | Consultation: 30 min weekly over 8 wk.; In class coaching: twice-weekly for 10–14 wk., 20 min for each Te. | Yes (Video-modeling) | Yes (booster coaching for 6 wk.) | no |

| Fukkink et al. (2010), the Netherlands [26] | Video Interaction Guidance for Childcare | yes | yes | no | yes | In person | no | - | Yes (teachers were videotaped while working with their groups + detailed discussion of video clips selected by trainer) | 4 sessions | Yes (Video-feedback) | no | Yes (no int.) |

| Garbacz et al. (2014), USA [27] | Teacher-Child Interaction Training | yes | yes | yes | no | In person | Yes (Workshops, discussions, practice worksheets, role playing, modeling) | 9 sessions once a wk. (1.5 h each) | Yes (in class coaching with live coaching and feedbacks) | 2 time per wk. over 6–8 wk. | Yes (Video-modeling) | no | no |

| Garner et al. (2019), USA [28] | Creative Curriculum (CrC) and Responsive Classroom (RC) | yes | yes | no | no | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | no |

| Gray (2015), USA [29] | Circle of Security-Parenting (COS-P) | yes | yes | no | no | In person | Yes (Discussion, psycho-education, handhouts, videos) | 8 wk., 90 min each session | no | - | Yes (Video-modeling) | no | Yes (no int.) |

| Groeneveld et al. (2011), the Netherlands [30] | VIPP-CC | adapted | yes | yes | no | In person | no | - | Yes (videofeedback) | 6 visits | Yes (Video-feedback) | no | Yes (6 phone calls to talk about general developmental topics) |

| Groeneveld et al. (2016) the Netherlands [4] | VIPP-CC | yes | yes | yes | no | In person | no | - | Yes (videofeedback) | 6 visits | Yes Video-feedback | no | Yes (6 calls lasted 15–30 min each to talk about general developmental topics) |

| Helmerhost et al. (2017), the Netherlands [8] | Caregiver Interaction Profile training | no | yes | yes | yes | In person | Yes (Shared experiences with colleagues) | 1 final session | Yes (videofeedback) | 4 sessions (each 2 h) | Yes (Video-feedback) | no | Yes (no int.) |

| Jilink et al. (2018), the Netherlands [31] | Video Interaction Guidance + Early Education Training (ECE) | yes | yes | yes | yes | In person | no | - | Yes ECE = face to face feedback with discussion in class. VIG = Te. Are videotaoed and then shared sessions of video-feedback with the coach | ECE = 9- 2.5 h sessions + 2 biannual meetings 2.5 h focusing on implementation VIG = 4 sessions in 16 wk. each 30 min | ECE: no VIG: yes (video-feedback) | no | Yes (no int.) |

| Lyon et al. (2009), USA [32] | Teacher–Child Interaction Training | adapted | yes | yes | no | In person | Yes (Workshops, discussions, practice worksheets, role playing) | 9 sessions once a wk. (1.5 h each) | Yes (In class coaching with live coaching and written feedbacks) | 1–3 wk. for 20 min over 2–4 wk. | no | - | no |

| Moreno et al. (2015), USA [33] | Expanding Quality for Infants and Toddlers (EQ) | no | yes | yes | yes | In person | Yes (College coursework, applied exercises, textbook) | 48 h | Yes EQ0: no EQ5 = in-class coaching with feedback EQ15 = in-class coaching with feedback | EQ0: - EQ5: 5 h EQ15:15 h | no | no | Yes CC = students of the community college course; CG = no int. |

| Werner et al., (2018), the Netherlands [5] | VIPP-CC | yes | yes | yes | no | In person | no | - | Yes (Te. Are videotaped and then received video-feedback) | 6 intervention visists (1.5 h each 2–4 weeks apart) | Yes (Video-feedback) | no | Yes (6 calls lasted 15 each to talk about general developmental topics + brochure about play materials) |

| Zan and Ritter (2014), USA [34] | Coaching and Mentoring for Preschool Quality | no | yes | yes | yes | In person | Yes (Workshops, role-playing, videos, discussions) | 4 bimontly 3 h workshops;Monthly self-reflection | Yes (video-base self-reflection on own videos usign written guides; + peer coaching with teachers’ assistants; + mentoring with class. Teams) | self-reflection monthly; Peer coaching meetings (20–45 min); Monthly class mentoring, 1 h | Yes (Video-modeling Self-reflection on own videos) | no | Yes (no int.) |

3.2.1. Teacher–Child Interaction Dimensions Targeted by Interventions

Emotional Support

Classroom Organization (CO)

Instructional Support (IS)

3.2.2. Interventions Structure

3.3. Measured Variables

| Authors (Year), Country | Measured Variables | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictors/Covariates | Moderators | Acceptability/Satisfaction/Usefulness (by Te.) | Agreement Te.-Experts | ||||||||

| Evaluated with Structured Obs. | Evaluated with Self-Report Q. (by Experts) | Evaluated with Self-Report Q. (by Te.) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Pre-Post | Evaluated by | Rating Scale Used | |||||||||

| Val. | Adap. | Ad-hoc | ||||||||||

| Baker-Henningham et al. (2009), Jamaica [21] | Te. positive and negative behav. and commands; Te. promoting Ch. social and emotional competences; Ch. appropriate behav. and level of interest and enthusiasm; Te. provides opportunities for Ch. to share and help each other; Te. warmth | yes | Expert | yes | yes | no | - | Ch. Behav. in class. (ad-hoc Q.); Ch. Behav. perceived to be more difficult (ad-hoc Q.) | - | - | Teacher satisfaction with Int. (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Biringen et al. (2012), USA [22] | Caregiver-Ch. relational quality (EA); Child’s attachment relevant behav. to the adult; Caregiver’s overall style within the whole class. | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Driscoll et al. (2011), USA [23] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Ch. Language/literacy skills (Q.); Child social-emotional competence (Q.); Ch-Te. Relationship (Q.) | Ch. Characteristic: Scores; Sex; Race; Maternal Education; Class. Characteristics: english proficient; individualized education plan; -. ch. enrolled; family income-to-needs ratio; Te. Characteristics; Adult-centered beliefs about educating children (Q); Self-efficacy (Q.); Advanced degree; Educational background; Support Received (study condition); Minutes on Web; Implementation (yes/-); | - | - | - |

| Early et al., (2017), USA [6] | Te.-Ch. Interaction (ES,CO,IS) | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Knowledge of effective Te.-Ch. Interactions (Q.); Perceived value of the int. (Q.); Relationship with the coach/instructor (Q.) | - | Te. centered beliefs on educating Ch. (Q.); Coach/Instructor centered beliefs on educating Ch. (adapted Q.); Coach/Instructor k-wledge of effective Te.-Ch- interactions (adapted Q.); Coach/Instructor confidence in their understanding of CLASS tools (Q.); | - | - |

| Fabiano et al. (2013), USA [24] | Te.-Ch. Interaction (CO) Frequency of ch. and te. behav. | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Overall Class. functioning (Adapted Q.); | - | - | Teacher satisfaction with Int. (Adapted Q.) | - |

| Fawley et al. (2020), USA [25] | Te. behav.; Child. behav. | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Ch. social and behav. competence (Q.) | - | - | Satisfaction with the training program (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Fukkink et al. (2010), the Netherlands [26] | Behav. of caregivers; Interactions with Ch.; sensitive responsivity; verbal stimulation; nonverbal interactions’ component (micro-level) | yes | Expert | yes | no | yes | - | Work satisfaction (Q.); | - | - | Perceived competence of teachers (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Garbacz et al. (2014), USA [27] | Te. Behav. | yes | Expert | no | yes | no | - | Social–emotional strengths and behav. concerns in Ch. (Q.) | - | - | Usefulness of training (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Garner et al. (2019), USA [28] | Ch. and Te. Behav. | no | Expert | yes | no | no | - | beliefs about guiding ch. social-emotional development (Q.) | Te. Level of education and experience; Curriculum type; Gender composition of Te.-Ch- interactions; Te. Beliefes about guiding children’s social-emotional development | - | - | - |

| Gray (2015), USA [29] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Stress and depressive symptoms (Q.) Self-efficacy and competence in supporting ch. scoioemotional development (Q.) Reflective functioning (Q.) | - | Feedback on intervention efficacy and on their perceptions (Ad-hoc Q.) | - | |

| Groeneveld et al. (2011), the Netherlands [30] | Caregiver Sensitivity Global quality of childcare (quality and quantity of stimulation and support available to a ch.) | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Attitude toward sensitive caregiving and limit setting (Q.); | - | Caregiver feedback (Ad-hoc Q.) | - | |

| Groeneveld et al. (2016) the Netherlands [4] | Ch. Wellbeing (general positive state of the Ch.-the extent to which ch. Fell safe, self-confident, relaxed and enjoy activities); | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | - | Global quality of childcare (quality and quantity of stimulation and support available to a child) (structured Obs. + rating scale); Caregiver Sensitivity (structured Obs. + rating scale); mo. Spent with trusted caregiver; | - | - |

| Helmerhost et al. (2017), the Netherlands [8] | Caregiver interaction skills; | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | Global childcare quality (structured Obs.) | - | - | - |

| Jilink et al. (2018), the Netherlands [31] | Te. Interactive skills | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lyon et al. (2009), USA [32] | Teacher in interactions with Ch.; | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | - | - | satisfaction with Intervention (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Moreno et al. (2015), USA [33] | Te. Interaction skills | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Knowledge on infant-toddler development (Ad-hoc Q.); Self-efficacy (Adapted Q.) | Modernity in education practicing with Ch. (Q.); Negative views toward childcare field (Ad-hoc Q.); professional status | - | - | - |

| Werner et al., (2018), the Netherlands [5] | Cargiver sensitive responsiveness; General childcare quality; | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | Attitude toward caregiving (Q.); | Ch. Group size; Caregiver-Ch. Ratio; | - | Intervention Evaluation (Ad-hoc Q.) | - |

| Zan and Ritter (2014), USA [34] | Te. Interaction skills | yes | Expert | yes | no | no | - | - | Te. Education level | - | - | - |

3.3.1. Outcome Variables

3.3.2. Predictors, Covariates, and Moderators

- Teachers’ characteristics with regards to their level of education and the years of teaching experience [23,28,33,34], beliefs about educating children [23,33], self-efficacy [23], negative views toward childcare field [33], beliefs about guiding children’s social-emotional development [28], and Global Childcare quality (quality and quantity of stimulation and support available to a child) [8].

3.4. Main Results

| Authors (Year), Country | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Results at Post-Test/Follow-Up | Predictors | Moderators | Acceptability/Satisfaction/Usefulness (by Te.) | ||

| Teachers | Children | ||||

| Baker-Henningham et al. (2009), Jamaica [21] | IG > positive Te. Behav.; < negative Te. behav.; = Te. commands; CG > negative Te. behav.; > Te. commands; = Te. positive behav.; > IG Te. warmth than CG; IG Te. Provided > opportunities for children to share and help each other than CG; | IG Ch. > appropriate behav. and interest and enthusiasm than CG; 12/14 IG Te. reported that Ch. behav. improve; Te. reported that Ch. behav.remained the same or got worse. | - | - | positive |

| Biringen et al. (2012), USA [22] | IG caregiver > structuring over time, CG <; IG caregiver > sensitivity over time, CG <; IG caregiver Supportiveness over time>, CG <; IG caregiver Hostility over time<, CG >; IG caregiver Detachment over time<, CG >; | IG Ch. > Responsive over time, CG <; IG Ch. emotionally secure > over time; CG Ch. =; | - | - | - |

| Driscoll et al. (2011), USA [23] | Ch. who participated in int. developed closer relationships with their Te. over the course of the school year (Closeness) than Ch. who did not participate; | Scores; Minutes on wesite; Impelementation; | - | - | |

| Early et al., (2017), USA [6] | MMCI Te > ES, IS, than CG; MTP Te. > ES than CG; MMCI Te. Knowledge > MTP Te. And CG; both MMCI and MTP Te. perceived their professional development as more valuable than CG; MTP Te. > positive views of the coach/instructor than MMCI Te. | - | - | MMCI*less education -> ES, CO; MMCI*metropolitan area -> IS; MMCI*coach with > years of experience -> IS; MTP*fewer ch. Per adult -> IS | - |

| Fabiano et al. (2013), USA [24] | 1FU I Te. > behav. management-related procedures and Instructional learning formats than W; 3FU W Te. < praise statements than I e. Consultation < functioning class. | - | - | - | positive I > useful than W; |

| Fawley et al. (2020), USA [25] | < Te. Structuring behav.; < Te. Negative Talk for Class B; | Te. indicated positive child behav. change: < Behavioral Concerns and > Total Protective Factors; | - | - | Positive |

| Fukkink et al. (2010), the Netherlands [26] | IG Te. > frequent eye contact.; IG Te. > verbally received the initiatives of Ch.; G Te. > allowed Ch. to take turns; IG teachers responded to the initiatives of Ch. < CG; | - | - | - | Te. > confident in their work |

| Garbacz et al. (2014), USA [27] | Te. skill use > over the course of the training; Te. > skill use associated with > Ch. > socio-emotionl strenghts and < beahav. Concerns; | > socio-emotionl strenghts and < beahav. Concenrns; > protective factors especially for at-risk Ch. | - | - | Positive |

| Garner et al. (2019), USA [28] | Te. and Ch. in CrC > negative facial expressions than RC; Te. > social-emotional teaching practices < negative facial emotions and > talk about emotions; | - | Te. and Ch. in CrC > negative facial expressions than RC; Te. > social-emotional teaching practices < negative facial emotions and > talk about emotions; interactions with boys only < Te. facial emotion expression; interactions with girls only > Ch. negative facial expression; Te. > negative facial expression or lack of facial expression was also more likely when Ch. > negative emotion; < Te. social-emotional practices > Ch. negative facial expression; Te. > or negative emotions Ch. facial epression | - | - |

| Gray (2015), USA [29] | IG Te. > self-efficacy and competence managing ch. challenging behaviors and supporting their socioemotional development | - | - | - | positive |

| Groeneveld et al. (2011), the Netherlands [30] | Global quality increase in IG; >positive attitude toward caregiving and limit setting than CG; | - | - | - | positive |

| Groeneveld et al. (2016) the Netherlands [4] | Both IG and CG increased Ch. Wellbeing with time; | - | - | In IG Ch. Wellbeing > when they were more familiar with the caregiver | - |

| Helmerhost et al. (2017), the Netherlands [8] | IG Te. > sensitive responsiveness, respect for auto-my, verbal communication and fostering positive peer interactions; | - | - | - | - |

| Jilink et al. (2018), the Netherlands [31] | VIG, ECE, and VIG + ECE Te. showed on average > interactive skills compared to CG Te.; ECE effective for Te. verbal communication and developmental stimulation; VIG effective for Te. interactive skills with regard to fostering peer interactions between children; ECE + VIG effective for Te. verbal communication and fostering peer interactions between ch. | - | - | - | - |

| Lyon et al. (2009), USA [32] | Great improvement from baseline to first phese of int.; The largest mean behavioral gains were observed in the use of unlabeled praise, which increased from an overall mean of 5% at baseline to 9% post-int.; Te. increased their use of behavioral descriptions, reflections, and labeled praise; Inspection of individual teachers’ data suggested that 10 Te. demonstrated > positive behavior over the course of training. | - | - | - | positive |

| Moreno et al. (2015), USA [33] | EQ had little effect over time on self-efficacy and k-wledge; EQ15 displayed the most consistent pattern of improvements, specifically in the area of support for language and learning. | - | Modernity -> self-efficacy; professional status -> support for language and learning skills; | - | - |

| Werner et al., (2018), the Netherlands [5] | >IG Te. sensitive responsiveness; <CG Te. sensitive responsiveness; In IG, structured play situations accounted for > sensitivity over time, while in CG < sensitivity over time; Childcare quality > in both groups; IG > positive attitude towards caregiving and limit setting than CG. | - | - | - | positive and IG > of CG |

| Zan and Ritter (2014), USA [34] | IG Te.: >behav. Management, Productivity, Quality of Feedback, Language modeling; CG Te.: >Negative Climate and < Student Perspective. | - | Behav. management, Productivit, Quality of Feedback, Language modeling > in both degreed and -n-degreed with very little differences | - | - |

3.4.1. Effect of Intervention at Post-Test or Follow-Up

3.4.2. Significant Predictors, Covariates, and Moderators

4. Discussion

4.1. Participant Characteristics

4.2. Intervention Characteristics

4.3. Measured Variables and Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation, 1st ed.; Psychological Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, A.M.; Fearon, R.; van Ijzendoorn, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Roisman, G.I. Attachment in the Early Life Course: Meta-Analytic Evidence for Its Role in Socioemotional Development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2016, 11, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, M.G.; Vermeer, H.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Linting, M. Randomized Video-Feedback Intervention in Home-Based Childcare: Improvement of Children’s Wellbeing Dependent on Time Spent with Trusted Caregiver. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Werner, C.D.; Vermeer, H.J.; Linting, M.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Video-feedback intervention in center-based child care: A randomized controlled trial. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 42, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, D.M.; Maxwell, K.L.; Ponder, B.D.; Pan, Y. Improving teacher-child interactions: A randomized controlled trial of Making the Most of Classroom Interactions and My Teaching Partner professional development models. Early Child. Res. Q. 2017, 38, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Learning Opportunities in Preschool and Early Elementary Classrooms. In School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability; Pianta, R.C., Cox, M.J., Snow, K.L., Eds.; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst, K.O.W.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M.A.; Fukkink, R.G.; Tavecchio, L.W.C.; Deynoot-Schaub, M.J.J.M.G. Effects of the Caregiver Interaction Profile Training on Caregiver–Child Interactions in Dutch Child Care Centers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 46, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, H.J.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. Attachment to mother and nonmaternal care: Bridging the gap. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2008, 10, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denham, A.S.; Wyatt, T.M.; Bassett, H.H.; Echeverria, D.; Knox, S.S. Assessing social-emotional development in children from a longitudinal perspective. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, i37–i52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, C.D.; Linting, M.; Vermeer, H.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M. Do Intervention Programs in Child Care Promote the Quality of Caregiver-Child Interactions? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, E.; McCartney, K.; Taylor, B.A. Does Higher Quality Early Child Care Promote Low-Income Children’s Math and Reading Achievement in Middle Childhood? Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1329–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, J.; Vandell, D.L.; Burchinal, M.; Clarke-Stewart, K.A.; McCartney, K.; Owen, M.T. NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Dev. 2007, 8, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, K.O.W.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M.; Vermeer, H.J.; Fukkink, R.G.; Tavecchio, L.W.C. Measuring the Interactive Skills of Caregivers in Child Care Centers: Development and Validation of the Caregiver Interaction Profile Scales. Early Educ. Dev. 2014, 25, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; La Paro, K.M.; Hamre, B.K. Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink, R.G.; Lont, A. Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Child. Res. Q. 2007, 22, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egert, F.; Dederer, V.; Fukkink, R.G. The impact of in-service professional development on the quality of teacher-child interactions in early education and care: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, C.; Morris, H.; Nolan, A.; Jackson, K.; Barrett, H.; Skouteris, H. Strengthening the quality of educator-child interactions in early childhood education and care settings: A conceptual model to improve mental health outcomes for preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 190, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.; Dunlap, G.; Hemmeter, M.L.; Joseph, G.E.; Strain, P.S. The teaching pyramid: A model for supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Child. 2003, 58, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.D.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Walker, S.; Powell, C.; Gardner, J.M. A pilot study of the Incredible Years Teacher Training programme and a curriculum unit on social and emotional skills in community pre-schools in Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biringen, Z.; Altenhofen, S.; Aberle, J.; Baker, M.; Brosal, A.; Bennett, S.; Coker, E.; Lee, C.; Meyer, B.; Moorlag, A.; et al. Emotional availability, attachment, and intervention in center-based child care for infants and toddlers. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, K.C.; Wang, L.; Mashburn, A.J.; Pianta, R.C. Fostering Supportive Teacher–Child Relationships: Intervention Implementation in a State-Funded Preschool Program. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, G.A.; Vujnovic, R.K.; Waschbusch, D.; Yu, J.; Mashtare, T.; Pariseau, M.E.; Pelham, W.E.; Parham, B.R.; Smalls, K.J. A comparison of workshop training versus intensive, experiential training for improving behavior support skills in early educators. Early Child. Res. Q. 2013, 28, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawley, K.D.; Stokes, T.F.; Rainear, C.A.; Rossi, J.L.; Budd, K.S. Universal TCIT Improves Teacher–Child Interactions and Management of Child Behavior. J. Behav. Educ. 2020, 29, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukkink, R.G.; Tavecchio, L.W. Effects of Video Interaction Guidance on early childhood teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, L.L.; Zychinski, K.E.; Feuer, R.M.; Carter, J.S.; Budd, K.S. Effects of teacher-child interaction training (TCIT) on teacher ratings of behavior change. Psychol. Sch. 2014, 51, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W.; Bolt, E.; Roth, A.N. Emotion-Focused Curricula Models and Expressions of and Talk About Emotions Between Teachers and Young Children. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2019, 33, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.A.O. Widening the circle of security: A quasi-experimental evaluation of attachment-based professional development for family child care providers. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2015, 36, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeneveld, M.G.; Vermeer, H.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Linting, M. Enhancing home-based child care quality through video-feedback intervention: A randomized controlled trial. J. Fam. Psychol. 2011, 25, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilink, L.; Fukkink, R.; Huijbregts, S. Effects of early childhood education training and video interaction guidance on teachers’ interactive skills. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2018, 39, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Gershenson, R.A.; Farahmand, F.K.; Thaxter, P.J.; Behling, S.; Budd, K.S. Effectiveness of Teacher-Child Interaction Training (TCIT) in a Preschool Setting. Behav. Modif. 2009, 33, 855–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.J.; Green, S.; Koehn, J. The Effectiveness of Coursework and Onsite Coaching at Improving the Quality of Care in Infant–Toddler Settings. Early Educ. Dev. 2014, 26, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, B.; Donegan-Ritter, M. Reflecting, Coaching and Mentoring to Enhance Teacher–Child Interactions in Head Start Classrooms. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2013, 42, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M.; Magnuson, K.; Powell, D.; Hong, S.S. Early Childcare and Education. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Ecological Settings and Processes; Bornstein, M.H., Leventhal, T., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 223–267. [Google Scholar]

- Rusby, J.; Taylor, T.; Marquez, B. Promoting Positive Social Development in Family Childcare Settings. Early Educ. Dev. 2004, 15, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, J.; Steinberg, L.; Belsky, J. Child-care history, classroom composition, and children’s functioning in kindergarten. Psych. Sci. 2007, 18, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Bridges, M.; Bassok, D.; Fuller, B.; Rumberger, R.W. How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Econ. Ed. Rev. 2007, 26, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abner, K.S.; Gordon, R.A.; Kaestner, R.; Korenman, S. Does Child-Care Quality Mediate Associations Between Type of Care and Development? J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, M.; Gampe, A.; Daum, M.M. Effects of the Type of Childcare on Toddlers’ Motor, Social, Cognitive, and Language Skills. Swiss J. Psychol. 2019, 78, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.A.; Colaner, A.C.; Usdansky, M.L.; Melgar, C. Beyond an “Either–Or” approach to home- and center-based child care: Comparing children and families who combine care types with those who use just one. Early Child. Res. Q. 2013, 28, 918–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Characteristics and quality of child care for toddlers and preschoolers. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000, 4, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentzou, K.; Sakellariou, M. The Quality of Early Childhood Educators: Children’s Interaction in Greek Child Care Centers. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 38, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreader, J.L.; Ferguson, D.; Lawrence, S. Infant and Toddler Child Care Quality (Research-to-Policy Connections No.2); Child Care & Early Education Research Connections: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, P.; Barnes, J.; Malmberg, L.; Sylva, K.; Stein, A.; the FCCC team 1. The quality of different types of child care at 10 and 18 months: A comparison between types and factors related to quality. Early Child Dev. Care 2008, 178, 177–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, T. Sequence of child care type and child development: What role does peer exposure play? Early Child. Res. Q. 2010, 25, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schipper, E.J.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M.; Geurts, S.A.; Derksen, J.J. General mood of professional caregivers in child care centers and the quality of caregiver–child interactions. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.K.; Pellerin, L. Effects of Multiple Features of Nonparental Care and Parenting in Toddlerhood on Socioemotional Development at Kindergarten Entry. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2020, 66, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, E.I.; Heckman, J.J.; Cameron, J.L.; Shonkoff, J.P. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10155–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kruif, R.E.; McWilliam, R.A.; Ridley, S.M.; Wakely, M.B. Classification of teachers’ interaction behaviors in early childhood classrooms. Early Child Res. Q. 2000, 15, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, J.T.; Locasale-Crouch, J.; Hamre, B.; Pianta, R. Teacher Characteristics Associated with Responsiveness and Exposure to Consultation and Online Professional Development Resources. Early Educ. Dev. 2009, 20, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, S.S.; Rice, J.; Boothe, A.; Sidell, M.; Vaughn, K.; Keyes, A.; Nagle, G. Social-Emotional Development, School Readiness, Teacher–Child Interactions, and Classroom Environment. Early Educ. Dev. 2012, 23, 919–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, K.R.; Cabell, S.Q.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. CLASS–Infant: An observational measure for as-sessing teacher–infant interactions in center-based child care. Early Ed. Dev. 2014, 25, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, A.C.; La Paro, K.M. Teachers’ Commitment to the Field and Teacher–Child Interactions in Center-Based Child Care for Toddlers and Three-Year-Olds. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2013, 41, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, D.M.; Bryant, D.M.; Pianta, R.C.; Clifford, R.M.; Burchinal, M.R.; Ritchie, S.; Barbarin, O. Are teachers’ education, major, and credentials related to classroom quality and children’s academic gains in pre-kindergarten? Early Child Res. Q. 2016, 21, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, J.; Sabol, T.J.; Hamre, B. Teacher–child interactions in the classroom: Toward a theory of within-and cross-domain links to children’s developmental outcomes. Early Ed. Dev. 2010, 21, 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotaman, H. Turkish early childhood teachers’ emotional problems in early years of their professional lives. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 24, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ragni, B.; Boldrini, F.; Buonomo, I.; Benevene, P.; Grimaldi Capitello, T.; Berenguer, C.; De Stasio, S. Intervention Programs to Promote the Quality of Caregiver–Child Interactions in Childcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111208

Ragni B, Boldrini F, Buonomo I, Benevene P, Grimaldi Capitello T, Berenguer C, De Stasio S. Intervention Programs to Promote the Quality of Caregiver–Child Interactions in Childcare: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111208

Chicago/Turabian StyleRagni, Benedetta, Francesca Boldrini, Ilaria Buonomo, Paula Benevene, Teresa Grimaldi Capitello, Carmen Berenguer, and Simona De Stasio. 2021. "Intervention Programs to Promote the Quality of Caregiver–Child Interactions in Childcare: A Systematic Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111208

APA StyleRagni, B., Boldrini, F., Buonomo, I., Benevene, P., Grimaldi Capitello, T., Berenguer, C., & De Stasio, S. (2021). Intervention Programs to Promote the Quality of Caregiver–Child Interactions in Childcare: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111208