“It Is Like We Are Living in a Different World”: Health Inequity in Communities Surrounding Industrial Mining Sites in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Tanzania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

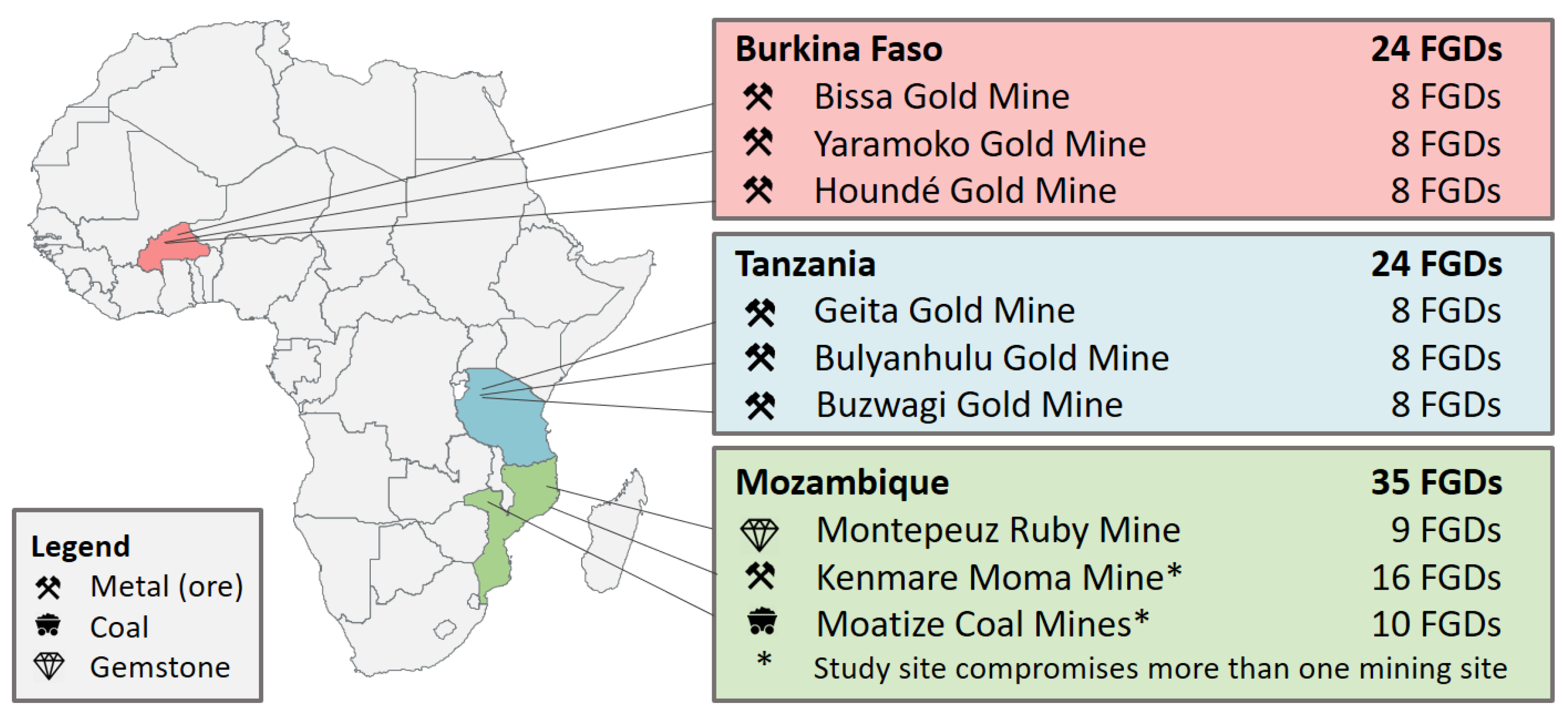

2.1. Study Set-Up

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Recruitment and Study Population

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

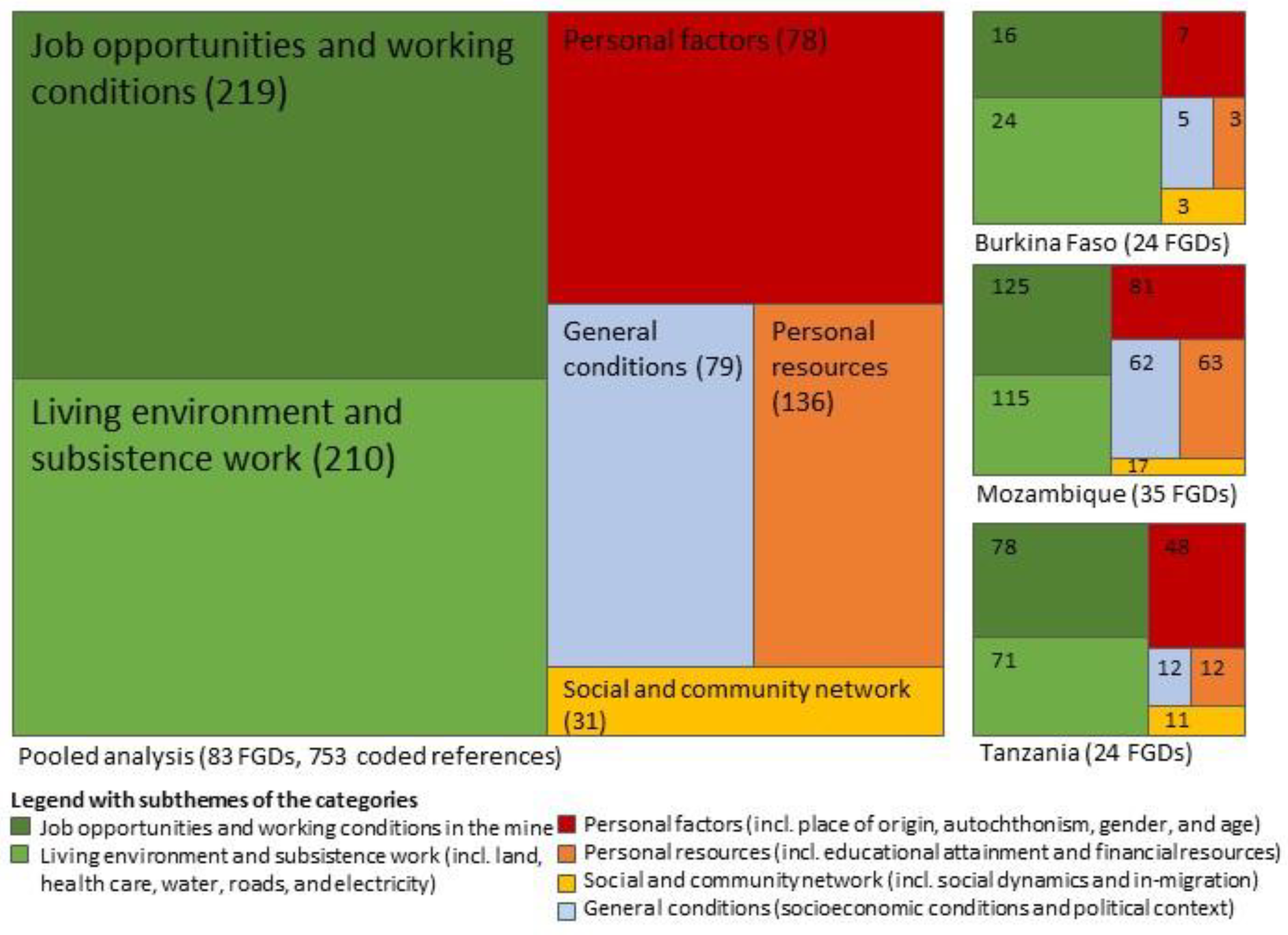

3. Results

3.1. Study Sites and Participants

3.2. Perceived Inequities

“Since [the mine] came to [our region] here, they have brought many problems to the people. By taking our land, they have brought many palaver between us. They have flatten us, as they have taken us to the mine and only employed us for six months and then left us again. Yet, you didn’t have your fields for cultivation anymore. Really, this is what causes problems. It can lead to crimes and thefts.”(BF3_L1)

3.2.1. Personal Factors: Place of Origin or Residence, Gender, and Age

“People living near the mine are not getting permanent employment opportunities, which have high salary. Getting high salary could enable us to provide for our families instead people coming from other regions are the ones getting good employment posts.”(TZ1_L5)

“This community is not healthy due to the works of these white people. […] Due to their activities, their blasting, affects us; we get different kinds of diseases.”(TZ2_L8)

3.2.2. Personal Resources

“Neither for jobs nor for anything they say that jobs already have owners […] the ones who know how to write and they used say that ‘you don’t know how to write’, but a long time ago they moralized us with jobs.”(MZ2.1_L6)

“We are very poor now it is because of these whites. In the past we were not that poor.”(MZ1_L4)

3.2.3. Social and Community Network

“The government is the one who causes the struggle, for you to be community leader you need to pay someone, now people are fighting to be community leader, those who had no decent house have built it […]. Those who never had a car now have a car, and so they are fighting to be community representatives, nowadays people have already opened their eyes, no one is robbed only the farmers who go to the fields all the time.”(MZ2.1_L4)

3.2.4. Living Environment and Subsistence Work

“The areas that everyone of us has exploited, were our property. In contrast, the area of the mine, which we are occupying today, is the property of these “white” [from the mine]. Why [?] Because the certificate for residential area as promised by the responsible from the mine, we did not receive it […]. Because you are not the owner of something, you are always living with fear. This problem affects our sleep.”(BF1_L5)

“The presence of dispensary is not for the intention of saving our lives but to destroy us because if it wouldn’t have been their mining activities, we wouldn’t have been getting sick frequently.”(TZ3_L4)

3.2.5. Job Opportunities and Working Conditions

“They are employing chef who gets high salary while that job can be done by one of us from this community. When they were introducing the mining company they said natives will benefit a lot from the mining but we are only getting temporary employment for two weeks or two months or three.”(TZ2_L1)

3.2.6. General Socioeconomic Conditions and Political Context

“In any case, the authorities must know that their power come from the people and without the people there is no power. In this regard, the government has the obligation to surveil the health of the population.”(BF1_L5)

3.3. Consistency of Findings across Countries

4. Discussion

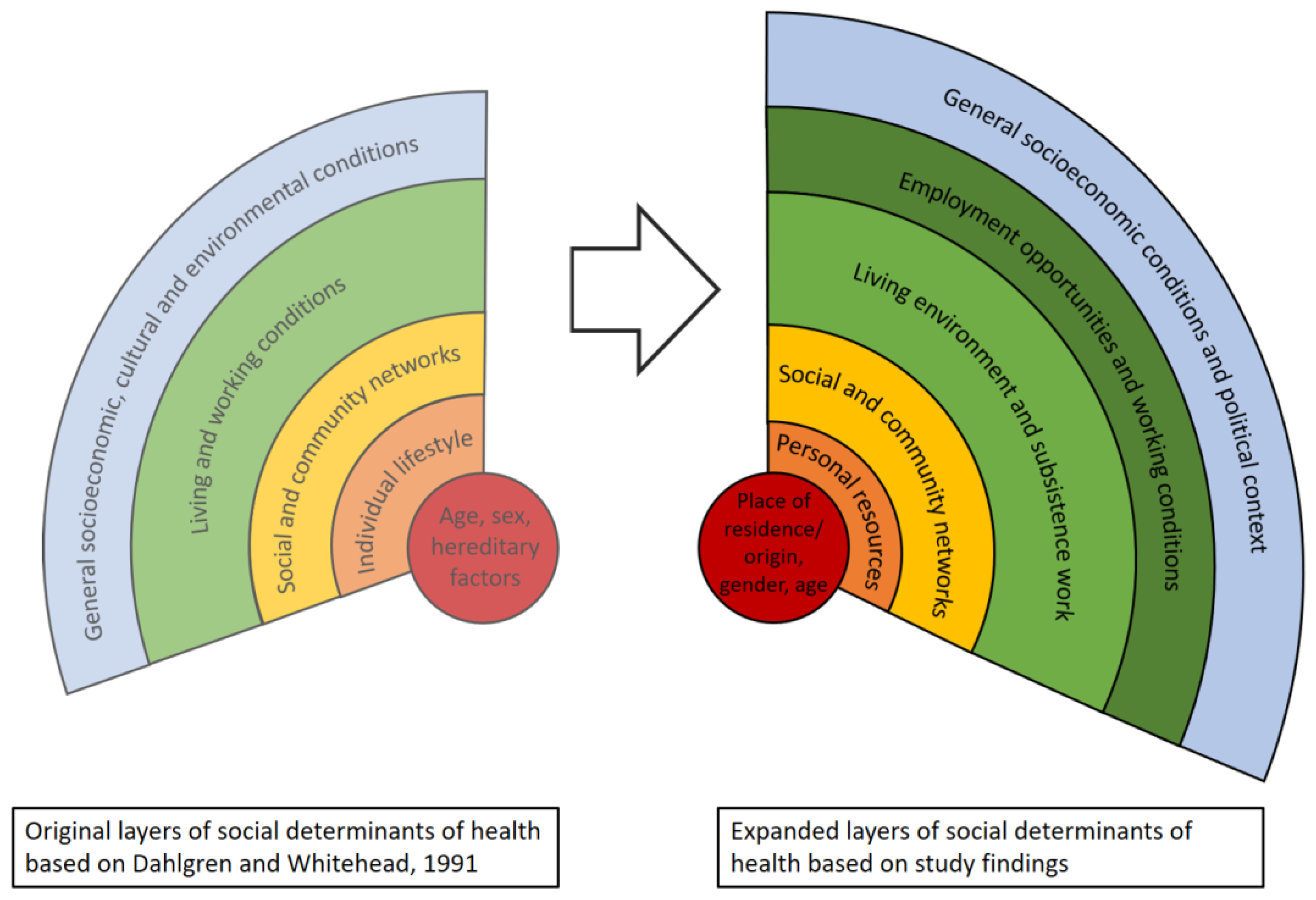

4.1. Complexity of Health Inequities

4.2. Locating Our Findings in a Model of Health Determinants

4.3. Addressing Health Inequities

4.4. Addressing Health Inequities in the Context of Extractive Industries

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| “Layer” | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Personal Factors | |

| Place of origin and residence |

|

| Gender |

|

| Ethnicity |

|

| Age |

|

| Personal resources | |

| Educational background |

|

| Monetary |

|

| Social and community network | |

| Social status |

|

| Relationship to the mine |

|

| In-migration |

|

| Living environment and subsistence work | |

| Land |

|

| Housing |

|

| Health care |

|

| Road network |

|

| Electricity |

|

| Job opportunities and working conditions | |

| Job opportunities |

|

| Working conditions |

|

| General socio-economic political conditions | |

| Socio-economic |

|

| Political |

|

References

- Fraser, J. Creating shared value as a business strategy for mining to advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.S.; Adongo, P.B.; Binka, F.; Brugger, F.; Diagbouga, S.; Macete, E.; Munguambe, K.; Okumu, F. Health impact assessment for promoting sustainable development: The HIA4SD project. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2020, 3, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, S.; Javadi, D.; Andrey, J.; Ghaffar, A.; Labonte, R. Health intersectoralism in the Sustainable Development Goal era: From theory to practice. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- RMF; CCSI. Mining and the SDGs a 2020 Status Update; Responsible Mining Foundation (RMF), Columbia Center on Sustainble Investment (CCSI): New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The Growing role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNECA. Minerals and Africa’s Development; United Nations Economic Commission for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Viliani, F.; Edelstein, M.; Buckley, E.; Llamas, A.; Dar, O. Mining and emerging infectious diseases: Results of the infectious disease risk assessment and management (IDRAM) initiative pilot. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, A.D.; Zwi, A.B. Public-private partnerships and global health equity: Prospects and challlenges. Indian J. Med Ethics 2007, 4, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utzinger, J.; Wyss, K.; Moto, D.; Tanner, M.; Singer, B. Community health outreach program of the Chad-Cameroon petroleum development and pipeline project. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 4, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoblauch, A.M.; Farnham, A.; Zabre, H.R.; Owuor, M.; Archer, C.; Nduna, K.; Chisanga, M.; Zulu, L.; Musunka, G.; Utzinger, J.; et al. Community health impacts of the Trident Copper Mine Project in northwestern Zambia: Results from repeated cross-sectional surveys. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrecker, T.; Birn, A.-E.; Aguilera, M. How extractive industries affect health: Political economy underpinnings and pathways. Health Place 2018, 52, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamu, J.; Le Billon, P.; Spiegel, S. Extractive industries and poverty: A review of recent findings and linkage mechanisms. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaf, J.; Baum, F.; Fisher, M.; London, L. The health impacts of extractive industry transnational corporations: A study of Rio Tinto in Australia and Southern Africa. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, A.; Winkler, M.S.; Cambaco, O.; Cossa, H.; Kihwele, F.; Lyatuu, I.; Zabré, H.R.; Eusebio, M.; Munguambe, K. Health impacts of industrial mining on surrounding communities: Local perspectives from three sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendryx, M. The public health impacts of surface coal mining. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emel, J.; Makene, M.H.; Wangari, E. Problems with reporting and evaluating mining industry community development projects: A case study from Tanzania. Sustainability 2012, 4, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mzembe, A.N.; Downs, Y. Managerial and stakeholder perceptions of an Africa-based multinational mining company’s corporate social responsibility (CSR). Extr. Ind. Soc. 2014, 1, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeti, T.; Madureira Lima, J.; Yang, L.; Brown, C. Leaving no one behind: Health equity as a catalyst for the Sustainable Development Goals. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, i24–i27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, G.; Corbin, J.H.; Miedema, E. Sustainable Development Goals for health promotion: A critical frame analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 2007, 370, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, A.; Valentine, N.; Brown, C.; Loewenson, R.; Solar, O.; Brown, H.; Koller, T.; Vega, J. The Commission on Social Determinants of Health: Tackling the social roots of health inequities. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worku, E.B.; Woldesenbet, S.A. Poverty and inequality–but of what-as social determinants of health in Africa? Afr. Health Sci. 2015, 15, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- GBD 2016 SDG Collaborators. Measuring progress and projecting attainment on the basis of past trends of the health-related Sustainable Development Goals in 188 countries: An analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1423–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CCSDH. A Review of Frameworks on the Determinants of Health; Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health (CCSDH): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. About Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/ (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- WHO. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Debates, Policy & Practice, Case Studies; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Task Force on Research Priorities for Equity in Health; WHO Equity Team. Priorities for research to take forward the health equity policy agenda. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 948–953. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, V. What we mean by social determinants of health. Int. J. Health Serv. 2009, 39, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucyk, K.; McLaren, L. Taking stock of the social determinants of health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borde, E.; Hernandez, M. Revisiting the social determinants of health agenda from the global South. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, A.; Farnham, A.; Azevedo, S.; Cossa, H.; Dietler, D.; Nimako, B.; Adongo, P.B.; Merten, S.; Utzinger, J.; Winkler, M.S. Health impact assessment and health equity in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 79, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Mining industry and sustainable development: Time for change. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpalu, W.; Normanyo, A.K. Gold mining pollution and the cost of private healthcare: The case of Ghana. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Goltz, J.; Barnwal, P. Mines: The local wealth and health effects of mineral mining in developing countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 139, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusah-Karikari, A. Black gold in Ghana: Changing livelihoods for women in communities affected by oil production. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, E.; Nuur, C. Social sciences and the mining sector: Some insights into recent research trends. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Ramirez, J.; Sly, P.D.; Ng, J.; Jagals, P. Using human epidemiological analyses to support the assessment of the impacts of coal mining on health. Rev. Environ. Health 2019, 34, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.J. A framework for integrated environmental health impact assessment of systemic risks. Environ. Health 2008, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pope, C.; Mays, N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995, 311, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.A.; Tabaac, A.; Jung, S.; Else-Quest, N.M. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M.; Shelton, R.C.; Kegler, M. Advancing the science of qualitative research to promote health equity. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buse, K.; Hawkes, S. Health in the Sustainable Development Goals: Ready for a paradigm shift? Glob. Health 2015, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farnham, A.; Cossa, H.; Dietler, D.; Engebretsen, R.; Leuenberger, A.; Lyatuu, I.; Nimako, B.; Zabre, H.R.; Brugger, F.; Winkler, M.S. Investigating health impacts of natural resource extraction projects in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mozambique, and Tanzania: Protocol for a mixed methods study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e17138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health; Institute for Futures Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health at WHO Headquarters; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, M. History of white-collar workers. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2001, 16496–16500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, A.; Kihwele, F.; Lyatuu, I.; Kengia, J.T.; Farnham, A.; Winkler, M.S.; Merten, S. Gendered health impacts of industrial gold mining in northwestern Tanzania: Perceptions of local communities. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.; Kabeer, N. Living with uncertainty: Gender, livelihods and pro-poor growth in rural sub-Saharan Africa. IDS Work. Pap. 2001, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Dietler, D.; Farnham, A.; de Hoogh, K.; Winkler, M.S. Quantification of annual settlement growth in rural mining areas using machine learning. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Issah, M.; Umejesi, I. Uranium mining and sense of community in the Great Karoo: Insights from local narratives. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buse, C.G.; Lai, V.; Cornish, K.; Parkes, M.W. Towards environmental health equity in health impact assessment: Innovations and opportunities. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Admiraal, R.; Sequeira, A.R.; McHenry, M.P.; Doepel, D. Maximizing the impact of mining investment in water infrastructure for local communities. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilson, G. An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot. Int. 1991, 6, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byakagaba, P.; Mugagga, F.; Nnakayima, D. The socio-economic and environmental implications of oil and gas exploration: Perspectives at the micro level in the Albertine region of Uganda. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llop-Girones, A.; Jones, S. Beyond access to basic services: Perspectives on social health determinants of Mozambique. Critical Public Health 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, V.; Kickbusch, I. Progressing the Sustainable Development Goals Through Health in All Policies: Case Studies from Around the World; Government of South Australia and World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky, O. Intersectionality 101; The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. International principles for social impact assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2003, 21, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.S.; Viliani, F.; Knoblauch, A.M.; Cave, B.; Divall, M.; Ramesh, G.; Harris-Roxas, B.; Furu, P. Health Impact Assessment International Best Practice Principles; In Special Publication Series No. 5; International Association for Impact Assessment: Fargo, ND, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, R.; den Broeder, L.; Furu, P.; Bond, A.; Cave, B.; Bos, R. Health Impact Assessment International Best Practice Principles; International Association for Impact Assessment: Fargo, ND, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO European Centre for Health Policy. Gothenburg Consensus Paper; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch, A.M.; Divall, M.J.; Owuor, M.; Archer, C.; Nduna, K.; Ng’uni, H.; Musunka, G.; Pascall, A.; Utzinger, J.; Winkler, M.S. Monitoring of selected health indicators in children living in a copper mine development area in northwestern Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knoblauch, A.M.; Divall, M.J.; Owuor, M.; Musunka, G.; Pascall, A.; Nduna, K.; Ng’uni, H.; Utzinger, J.; Winkler, M.S. Selected indicators and determinants of women’s health in the vicinity of a copper mine development in northwestern Zambia. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahoney, M.; Simpson, S.; Harris, E.; Aldrich, R.; Stewart Williams, J. Equity-Focused Health Impact Assessment Framework; Australasian Collaboration for Health Equity Impact Assessment (ACHEIA): Newcastle, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) Workbook; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salcito, K.; Utzinger, J.; Krieger, G.R.; Wielga, M.; Singer, B.H.; Winkler, M.S.; Weiss, M.G. Experience and lessons from health impact assessment for human rights impact assessment. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2015, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SOPHIA Equity Working Group. How to Advance Equity Through Health Impact Assessments; Society of Practicitioners of Health Impact Assessment (SOPHIA): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C.; Ghosh, S.; Eaton, S.L. Facilitating communities in designing and using their own community health impact assessment tool. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandham, L.A.; Chabalala, J.J.; Spaling, H.H. Participatory rural appraisal approaches for public participation in EIA: Lessons from South Africa. Land 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addo-Atuah, J.; Senhaji-Tomza, B.; Ray, D.; Basu, P.; Loh, F.E.; Owusu-Daaku, F. Global health research partnerships in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietler, D.; Lewinski, R.; Azevedo, S.; Engebretsen, R.; Brugger, F.; Utzinger, J.; Winkler, M.S. Inclusion of health in impact assessment: A review of current practice in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.S.; Furu, P.; Viliani, F.; Cave, B.; Divall, M.; Ramesh, G.; Harris-Roxas, B.; Knoblauch, A.M. Current global health impact assessment practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, M.S.; Krieger, G.R.; Divall, M.J.; Cissé, G.; Wielga, M.; Singer, B.H.; Tanner, M.; Utzinger, J. Untapped potential of health impact assessment. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thondoo, M.; Gupta, J. Health impact assessment legislation in developing countries: A path to sustainable development? Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2020, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Health in All Policies: Report on Perspectives and Intersectoral Actions in the African Region; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Closing the Health Equity Gap: Policy Options and Opportunities for Action; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelsbach, G. Exploring the Impact of Mining on Health and Health Service Delivery: Perceptions of Key Informants Involved in Three Different Gold Mining Communities in Burkina Faso. Master’s Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zürich), Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Burkina Faso (24 FGDs) | Mozambique (35 FGDs) | Tanzania (24 FGDs) | Total (83 FGDs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of study participants (and relative frequency in %) | ||||

| Male | 115 (49.8%) | 181 (48.0%) | 89 (48.6%) | 385 (48.7%) |

| Female | 116 (50.2%) | 196 (52.0%) | 94 (51.4%) | 406 (51.3%) |

| Total | 231 | 377 | 183 | 791 |

| Average number of participants per FGD (and range) | ||||

| Male | 10 (6–10) | 11 (6–12) | 8 (6–8) | 9 (6–12) |

| Female | 10 (7–10) | 11 (8–13) | 8 (6–10) | 9 (6–13) |

| Total | 10 (6–10) | 11 (6–13) | 8 (6–10) | 9 (6–13) |

| Average age in years (and age range) | ||||

| Male | 42 (23–71) | 45 (19–89) | 48 (19–77) | 45 (19–89) |

| Female | 31 (18–49) | 44 (29–83) | 42 (20–77) | 39 (18–83) |

| Total | 37 (18–71) | 44 (19–89) | 45 (19–77) | 42 (18–89) |

| Average years living in the community (and range) | ||||

| Male | 26 (3–67) | 37 (3–89) | 22 (2–66) | 30 (2–89) |

| Female | 13 (1–44) | 36 (1–83) | 19 (1–77) | 25 (1–83) |

| Total | 20 (1–67) | 37 (1–89) | 21 (1–77) | 28 (1–89) |

| Average number of years of school attended (and range) | ||||

| Male | 2.7 1 (0–10) | 3.8 (0–12) | 7.4 (0–14) | 4.4 (0–14) |

| Female | 1.2 1 (0–10) | 1.4 (0–12) | 7.3 (0–14) | 2.9 (0–14) |

| Total | 1.9 1 (0–10) | 2.6 (0–12) | 7.4 (0–14) | 3.6 (0–14) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leuenberger, A.; Cambaco, O.; Zabré, H.R.; Lyatuu, I.; Utzinger, J.; Munguambe, K.; Merten, S.; Winkler, M.S. “It Is Like We Are Living in a Different World”: Health Inequity in Communities Surrounding Industrial Mining Sites in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111015

Leuenberger A, Cambaco O, Zabré HR, Lyatuu I, Utzinger J, Munguambe K, Merten S, Winkler MS. “It Is Like We Are Living in a Different World”: Health Inequity in Communities Surrounding Industrial Mining Sites in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeuenberger, Andrea, Olga Cambaco, Hyacinthe R. Zabré, Isaac Lyatuu, Jürg Utzinger, Khátia Munguambe, Sonja Merten, and Mirko S. Winkler. 2021. "“It Is Like We Are Living in a Different World”: Health Inequity in Communities Surrounding Industrial Mining Sites in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Tanzania" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111015

APA StyleLeuenberger, A., Cambaco, O., Zabré, H. R., Lyatuu, I., Utzinger, J., Munguambe, K., Merten, S., & Winkler, M. S. (2021). “It Is Like We Are Living in a Different World”: Health Inequity in Communities Surrounding Industrial Mining Sites in Burkina Faso, Mozambique, and Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111015