Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors, and Risk Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Sampling Methods

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Scoring Criteria

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

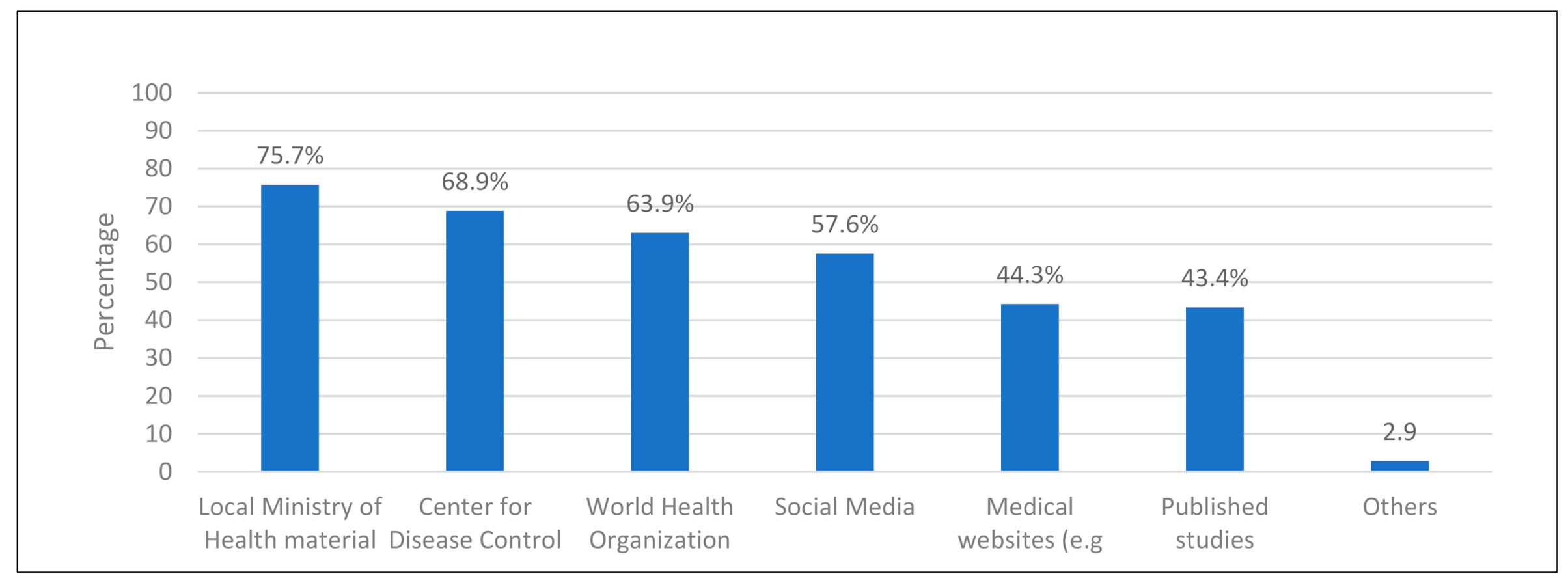

3.1. Assessment of Knowledge of COVID-19

3.2. Self-Reported Assessment of Preventive Behaviors

3.3. Assessment of Medical Students’ Risk Perception regarding COVID-19

3.4. Assessment of the Correlations between Knowledge, Preventive Behavior, and Risk Perception Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhagavathula, A.S.; Aldhaleei, W.A.; Rahmani, J.; Mahabadi, M.A.; Bandari, D.K. Knowledge and Perceptions of COVID-19 among Health Care Workers: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghrir, M.H.; Borazjani, R.; Shiraly, R. COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; a survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Arch. Iran. Med. 2020, 23, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Luo, W.; Li, H.-M.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Liu, X.-G.; Li, W.-T.; Li, Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control during Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/10665-331495 (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update and Interim Guidance on Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00427.asp (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. Responding to COVID-19: Real-Time Training for the Coronavirus Disease Outbreak. Available online: https://openwho.org/channels/covid-19 (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Modi, P.D.; Nair, G.; Uppe, A.; Modi, J.; Tuppekar, B.; Gharpure, A.S.; Langade, D. COVID-19 Awareness Among Healthcare Students and Professionals in Mumbai Metropolitan Region: A Questionnaire-Based Survey. Cureus 2020, 12, e7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Angawi, K.; Alshareef, N.; Qattan, A.M.N.; Helmy, H.Z.; Abudawood, Y.; Al-Qurashi, M.; Kattan, W.M.; Kadasah, N.A.; Chirwa, G.C.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Toward COVID-19 Among the Public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohel, K.H.; Patel, P.B.; Shah, P.M.; Patel, J.R.; Pandit, N.; Raut, A. Knowledge and perceptions about COVID-19 among the medical and allied health science students in India: An online cross-sectional survey. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahed, W.Y.A.; Hefzy, E.M.; Ahmed, M.I.; Hamed, N.S. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perception of Health Care Workers Regarding COVID-19, A Cross-Sectional Study from Egypt. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olum, R.; Chekwech, G.; Wekha, G.; Nassozi, D.R.; Bongomin, F. Coronavirus Disease-2019: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Health Care Workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.S. Middle East respiratory syndrome-related knowledge, preventive behaviours and risk perception among nursing students during outbreak. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2542–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olum, R.; Kajjimu, J.; Kanyike, A.M.; Chekwech, G.; Wekha, G.; Nassozi, D.R.; Kemigisa, J.; Mulyamboga, P.; Muhoozi, O.K.; Nsenga, L.; et al. Perspective of Medical Students on the COVID-19 Pandemic: Survey of Nine Medical Schools in Uganda. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Ying, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Ma, C. A cross-sectional study: Comparing the attitude and knowledge of medical and non-medical students toward 2019 novel coronavirus. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.; Shah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Fatokun, O. Knowledge and attitude of healthcare workers about middle east respiratory syndrome in multispecialty hospitals of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amri, S.; Bharti, R.; Alsaleem, S.A.; Al-Musa, H.M.; Chaudhary, S.; Al-Shaikh, A.A. Knowledge and practices of primary health care physicians regarding updated guidelines of MERS-CoV infection in Abha city. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, A.I.; Abu-Humeidan, A.; Alsulaiman, J.W.; Bloukh, S.; Ramadan, M.; Al-Shatanawi, T.N.; Awad, H.H.; Hijazi, W.Y.; Al-Kammash, K.R.; Obeidat, N.; et al. Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Precautionary Measures. A Descriptive Study from Jordan. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aker, S.; Midik, Ö. The Views of Medical Faculty Students in Turkey Concerning the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Data | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| • <25 years | 205 (63.5%) |

| • ≥25 years | 118 (36.5%) |

| Sex | |

| • Male | 237 (73.4%) |

| • Female | 86 (26.6%) |

| University attended | |

| • Unaizah Qassim University | 96 (29.7%) |

| • Almleda Qassim University | 116 (35.9%) |

| • Sulaiman Al Rajhi University | 111 (34.4%) |

| Academic level | |

| • 4th year | 103 (31.9%) |

| • 5th year | 100 (31.0%) |

| • Intern | 120 (37.1%) |

| Having medical knowledge about COVID-19 | |

| • Yes | 309 (95.7%) |

| • No | 14 (4.3%) |

| Statement | Correct Answer N (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. COVID-19 is a respiratory infection caused by a new species of virus in the coronavirus family | 312 (96.6%) |

| 2. The first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Wuhan, China | 319 (98.8%) |

| 3. The origin of COVID-19 in humans is likely through transmission from bats | 296 (91.6%) |

| 4. Its common symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but nausea and diarrhea are reported rarely | 279 (86.4%) |

| 5. Its incubation period is up to 14 days, with a mean of 5 days | 301 (93.2%) |

| 6. It can be diagnosed by PCR testing of samples collected from nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal discharge or from sputum and bronchial washing | 295 (91.3%) |

| 7. It is transmitted through respiratory droplets such as those generated by coughing and sneezing | 315 (97.5%) |

| 8. It is transmitted through close contact with an infected person (especially by family members and in crowded places and healthcare centers). | 306 (94.7%) |

| 9. The disease can be prevented through handwashing and personal hygiene | 302 (93.5%) |

| 10. A medical mask is useful to prevent the spread of respiratory droplets during coughing | 310 (96.0%) |

| 11. The disease can be prevented through maintaining no close contact, such as handshakes and kissing, not attending in-person meetings, and frequently disinfecting the hands | 312 (96.6%) |

| 12. All people in the society should wear face masks when going outside | 20 (6.2%) |

| 13. Only during aerosol generation procedures such as intubation, suction, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation do you have to wear an N95 mask | 207 (64.1%) |

| 14. The disease can be treated by usual antiviral drugs | 188 (58.2%) |

| 15. If symptoms appear within 14 days from direct contact with a suspected case, the person should inquire at a nearby ministry of health center | 278 (86.1%) |

| Statement | Yes (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. I canceled or postponed meetings with friends, eating out, and sporting events. | 293 (90.7%) |

| 2. I reduced the use of public transportation. | 297 (92.0%) |

| 3. I went shopping less frequently. | 300 (92.9%) |

| 4. I reduced visits to closed spaces, such as the library, theatre, and cinema. | 302 (93.5%) |

| 5. I avoided coughing around people as much as possible. | 311 (96.3%) |

| 6. I avoided places where a large number of people gathered. | 311 (96.3%) |

| 7. I increased the frequency of cleaning and disinfecting items that can be easily touched with my hands (i.e., door handles and surfaces). | 286 (88.5%) |

| 8. I washed my hands more often than usual. | 304 (94.1%) |

| 9. I discussed COVID-19 preventions with my family and friends. | 310 (96.0%) |

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Level of knowledge | |

| • Low | 5 (1.5%) |

| • Average | 47 (14.6%) |

| • High | 271 (83.9%) |

| Knowledge score (mean ± SD) | 12.5 ± 1.47 |

| Level of self-reported preventive behavior | |

| • Low | 2 (0.60%) |

| • Average | 17 (05.3%) |

| • High | 304 (94.1%) |

| Self-reported preventive behavior score (mean ± SD) | 8.40 ± 1.01 |

| Level of risk perception | |

| • Low | 102 (31.6%) |

| • Average | 149 (46.1%) |

| • High | 72 (22.3%) |

| Risk perception score (mean ± SD) | 5.34 ± 1.49 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsoghair, M.; Almazyad, M.; Alburaykan, T.; Alsultan, A.; Alnughaymishi, A.; Almazyad, S.; Alharbi, M.; Alkassas, W.; Almadud, A.; Alsuhaibani, M. Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors, and Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020842

Alsoghair M, Almazyad M, Alburaykan T, Alsultan A, Alnughaymishi A, Almazyad S, Alharbi M, Alkassas W, Almadud A, Alsuhaibani M. Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors, and Risk Perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020842

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsoghair, Mansour, Mohammad Almazyad, Tariq Alburaykan, Abdulrhman Alsultan, Abdulmajeed Alnughaymishi, Sulaiman Almazyad, Meshari Alharbi, Wesam Alkassas, Abdulaziz Almadud, and Mohammed Alsuhaibani. 2021. "Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors, and Risk Perception" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020842

APA StyleAlsoghair, M., Almazyad, M., Alburaykan, T., Alsultan, A., Alnughaymishi, A., Almazyad, S., Alharbi, M., Alkassas, W., Almadud, A., & Alsuhaibani, M. (2021). Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Preventive Behaviors, and Risk Perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020842