1. Introduction

Asthma is the most common pediatric chronic disease in the US, affecting nearly 10 million children (approximately 15%) under 18 years of age [

1,

2,

3]. It is also among the top three leading causes of hospitalizations among children. Acute asthma exacerbations require the patient to seek immediate (unscheduled) healthcare, including emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. Nearly 5 million children experience an asthma exacerbation each year in the US, accounting for an estimated 15 million missed school days, nearly 2 million ED visits, and greater than 60% of asthma-related costs. Past studies evaluating recurring visits (within one year) to pediatric EDs have found asthma to be the most common diagnosis within all recurring-visit groups and the most common diagnosis for high-frequency users (four or more recurring visits). In 2010, an evaluation of state Medicaid programs estimated a combined USD 272 million spent on asthma-related ED visits among children [

1,

2].

This study seeks to examine demographic and risk factor differences between children who visit the ED for asthma once (“one-time” ED patients) and those who visit the ED more than once (“repeat” ED patients) over an 18-month retrospective period, at an academic medical center. Before delving into the methods and results of this study, it would be important to take note of some essential background information for this study (described in the next section), which serves to provide not only the rationale for conducting this study, but also the broader context for interpreting its results.

2. Background

2.1. Pediatric Asthma-Related ED Visits Can Be Prevented by Improving Self-Management Effectiveness (SME)

According to the 2007 National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) evidence-based guidelines for asthma management and recent meta-reviews of the literature, “unscheduled healthcare use” for asthma, including ED visits, hospitalizations, and urgent care visits, can be prevented through effective self-management of asthma [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. To this effect, the guidelines emphasize the importance of creating a provider–patient partnership to activate patients to regularly monitor asthma symptoms, make necessary treatment adjustments, and take control of their disease. Concurrently, recent meta-reviews of studies on “supported self-management of asthma” have determined that interventions targeting the combination of

patient,

provider, and

organizational factors demonstrated the greatest improvement in health outcomes, compared to targeting patients or providers alone. As such, both the NHLBI guidelines and recent empirical research have underscored the need for increasing provider and organizational (hospital/clinic) engagement in asthma management. Nevertheless, gaps in adherence to NHLBI guidelines in routine clinical practice continue to persist.

2.2. Improving Pediatric Asthma SME Requires a “Holistic Framework” for Measuring SME

For widespread, systematic provider engagement in improving asthma SME (in routine clinical practice), a comprehensive set of resources for measuring SME is necessary, which currently does not exist. This gap could be attributed the fragmented nature of the asthma management literature. To date, no study has examined the concurrent impact of “provider–patient/family communication” and “patient/family activation” on both “medication adherence” (intermediate outcome of SME) and “unscheduled healthcare use” (primary outcome of SME) for asthma, while also controlling for an array of socio-ecological influences on asthma SME. Additionally, the existing literature on asthma SME has been largely restricted to cross-sectional studies, with limited use of validated measures of the aforementioned key constructs. Recognizing these gaps in the literature, researchers have recently worked to develop a “holistic framework” for measuring SME in childhood asthma [

9,

10]. The rationale behind this framework is as follows:

Extrinsic socioecological factors (individual demographic and risk factors, interpersonal factors, socioeconomic factors, health system factors including provider–patient/family communication on asthma management, community-level factors, and environmental-level factors) can impact

Intrinsic self-agency factors (patient/family activation in asthma management), to ultimately influence

SME in childhood asthma. SME in turn is defined by both primary outcomes (unscheduled healthcare use in children with asthma) and intermediate outcomes (asthma medication adherence and symptom control).

A figure summarizing the “holistic framework” for measuring SME in childhood asthma is available in an earlier (open access) publication led by the lead author [

10]. The purpose of the “holistic framework” is to guide empirical research investigating a comprehensive set of factors influencing childhood asthma SME and their interrelationships, to create a robust evidence base for generating resources for providers to measure and improve childhood asthma SME.

2.3. Need for Incremental Retrospective Studies to Develop Rationale for a Holistic Primary Study to Measure and Improve SME of Pediatric Asthma

Since a full-fledged research study informed by the “holistic framework” would involve substantial primary data collection efforts, an incremental approach to investigating interrelationships among key variables in the framework through retrospective chart review efforts could serve a dual purpose in (1) providing insight into key variables influencing SME while also (2) providing the foundation and rationale for a full-fledged study.

In keeping with this rationale, a first step to investigating interrelationships among variables in the “holistic framework” through retrospective chart review was undertaken in a recent study of demographic and risk factor differences between users and non-users of unscheduled healthcare for childhood persistent asthma. This earlier study was set in the outpatient clinics at the same institution and took a first step towards assessing SME in 59 children with asthma (8–17 years), informed by the “holistic framework”, by defining SME in terms of the primary outcome of unscheduled healthcare use. In the outpatient study, “users” of unscheduled healthcare served to represent “low SME”, while “non-users” of unscheduled healthcare within the same asthma severity category served to represent “high SME” [

11]. The study examined differences between users and non-users of unscheduled healthcare in persistent childhood asthma, with respect to select individual demographic and risk factors obtained through record review, including

asthma severity (defined as mild-persistent, moderate-persistent, and severe-persistent asthma),

age, gender, race, insurance, and

body-mass index (BMI).The results of the outpatient study were eye-opening. All three persistent asthma severity categories contained users and non-users of unscheduled healthcare, with “moderate-persistent” having a roughly equal distribution of users (11; 44%) and non-users (14; 56%). “Mild-persistent” had 4 users and 16 non-users, while “severe-persistent” had 10 users and 4 non-users. The only statistically significant finding from the study was that the “mild-persistent” category had fewer users than the “severe-persistent” category. However, after adjusting for severity, there were no significant differences between users and non-users on any other factor examined. In other words, although severity was statistically significant in explaining higher use of unscheduled healthcare, the fact remained that there were users and non-users of unscheduled healthcare use in all three severity categories for persistent childhood asthma. After adjusting for severity, none of the individual demographic and risk factors were statistically significant in explaining use of unscheduled healthcare in persistent childhood asthma. A key implication of these findings is that something other than the individual factors examined is driving unscheduled healthcare use in children with persistent asthma. Results from the outpatient study provided impetus for future primary research on factors influencing the SME of childhood asthma informed by the “holistic framework” including the roles of specific components of supported self-management of asthma, such as “provider–patient/family communication” and “patient/family activation”, in explaining differences in unscheduled healthcare use in childhood asthma.

The retrospective study described in this paper is set in the ED at the same (study) institution as the outpatient study. This study seeks to serve as a reinforcing incremental study seeking to understand factors influencing the SME of childhood asthma through retrospective review in order to provide impetus for future primary research on measuring and improving childhood asthma SME, informed by the “holistic framework”. Although the outpatient study served as an initial retrospective study, it was limited in sample size and restricted to a single setting. Obtaining results from a larger sample size in a different (ED) setting that serve to corroborate results from the outpatient setting has the potential to strengthen the rationale and foundation for future primary research. To this effect, the primary outcome of ED visits for childhood asthma in this study, which, in turn, is a prime example of unscheduled healthcare use, will serve as a proxy for SME of childhood asthma, as informed by the “holistic framework”. The remaining portion of this paper describes the purpose, methods, and results of this study.

3. Purpose

The research question of interest to this study is: What are the demographic and risk factor differences between children with “one-time” and “repeat” ED visits for childhood asthma? As described above, a key purpose of this paper is to provide a foundation for future research on childhood asthma SME, informed by the “holistic framework”. However, the paper also seeks to serve an additional purpose of contributing to the literature on ED utilization for childhood asthma. The existing literature has found the biggest determinants of ED utilization for childhood asthma to be access to care, disease severity, and socioeconomic factors. However, the vast majority of these studies have been undertaken among uninsured children and children with insurance coverage gaps [

1,

2,

3,

12,

13,

14]. The population of interest to this study is an insured population with access to primary and specialty outpatient care for childhood asthma. An understanding of demographic and risk factors influencing ED use for childhood asthma in this population therefore would serve as a useful complement to the existing literature.

In summary, the objective of this study is to examine differences between children who visit the ED for asthma once (“one-time” ED patients) and those who visit the ED more than once (“repeat” ED patients) over an 18-month retrospective period with respect to various demographic characteristics and risk factors. By gaining a better understanding of the individual factors influencing ED use for childhood asthma, this study seeks to serve the dual purpose of:

- (1)

Providing a foundation for future primary research on measuring and improving childhood asthma SME, informed by the “holistic framework”;

- (2)

Contributing to the literature on ED utilization for childhood asthma.

4. Methodology

The setting for this retrospective study was the emergency department (ED) at a children’s medical center, located within a public tertiary academic health system in Augusta, Georgia, USA. The population of interest was all unique pediatric patients (0–17 years) who visited the ED for primary clinical diagnosis of asthma between 1 January 2019 and 30 June 2020. Children were included in the study if they belonged to any of the following four severity categories for asthma (defined by NHLBI guidelines): intermittent, mild-persistent, moderate-persistent, or severe-persistent. Children with the potential for unrelated respiratory disease, including those with cystic fibrosis, congenital cardiac comorbidities, respiratory disease of prematurity, primary immunodeficiency, and neuromuscular disorders, were excluded from the study. The chart review was conducted by two medical students, under the supervision of a pediatric critical care faculty physician.

For the children who met study eligibility criteria, data were collected in the following three categories of data elements informed by the “holistic framework” (discussed earlier), through an 18-month retrospective review of each individual medical record:

Individual demographic factors, including: Round 1 analysis among 0–17-year-old children (<5 years, 5–9 years, >9 years); Round 2 analysis among 8–17-year-old children (8–12 years, 13–17 years); gender (male or female); race (Caucasian, African-American, other); insurance (Medicaid, private, other).

Individual risk factors, including: asthma severity category (intermittent, mild-persistent, moderate-persistent, or severe-persistent); BMI, defined as normal (<85%), overweight (85–95%), or obese (>95%); encounter type (ED-only; ED-to-inpatient; transfer ED-to-inpatient); primary care physician (PCP) (within study institution; outside study institution); encounter length of stay (LOS) (0 days; 1 day; 2 days; >2 days); socioeconomic risk (low, moderate, high).

Primary outcome of childhood asthma SME was assessed based on the number of ED visits over an 18-month retrospective timeframe and defined as: (1) patients who visited the ED once over the previous 18 months (“one-time”); (2) patients who visited the ED more than once over the previous 18 months (“repeat”).

While most of the data elements listed above are straightforward, a couple of them require additional clarification. For example, it would be relevant to note that the variable “encounter type” excludes all direct inpatient admits to the hospital (i.e., admissions that do not pass through the ED); the variable “socioeconomic risk” was obtained by aggregating five categories of data from record review: (1) housing or transportation issues, defined by notes by caregivers or social workers about mode of transport or change of addresses; (2) smoking exposure, defined as any exposure within the immediate family; (3) previous unplanned admission at any time, which would be indicated by a social work note; (4) more than three ED visits at any time, at any location, which would be indicated by a social work note; and (5) social dynamic factors, including any indication of familial or custody issues that could negatively affect the patient’s care. Based on the aggregated values, “socioeconomic risk” was categorized as “high”, “moderate”, or “low.”

There were two reasons for performing the second-round analysis for the age range 8–17 years. Firstly, this age interval is typically used for pediatric studies involving primary data collection, since children ≥ 8 years can be more confidently approached for completion of surveys and interviews (with parental consent) compared to children < 8 years [

15,

16]. Since future primary research on measuring and improving childhood asthma SME is being planned, it would be important for the preliminary retrospective studies to mirror those age ranges to enhance the comparability of the results. Secondly, there is a clinical rationale for preferring ≥ 8 years of age for studies related to pediatric asthma, since clinical diagnoses of asthma, including chronic, persistent asthma can be more reliably established in children ≥ 8 years of age due to the ability to perform pulmonary function testing (PFT), which is not feasible to implement for lower age-groups [

17,

18].

Differences between children with “one-time” vs. “repeat” visits to the ED were assessed with respect to aforementioned individual demographic and risk factors, using contingency table and logistic regression analysis.

5. Results

In Round 1 analysis (0–17 years), there were a total of 252 unique patients (children) who visited the ED at the study institution for asthma between January 2019 and June 2020. A retrospective review of each individual record over an 18-month timeframe revealed that 160 (63%) were “one-time ED” patients, whereas 92 (37%) were “repeat ED” patients. In other words, 92 patients visited the ED more than once over an 18-month timeframe. It would be relevant to note that although a total of 252 individual records were reviewed, not all contained complete data on every individual demographic and risk factor variable examined. Some of these variables contained missing values, as summarized in

Table 1 for Round 1 analysis. To clarify, the chart review process, which was conducted by clinical experts (two medical students under the supervision of a pediatric critical care physician), did in fact utilize a standardized data collection sheet. However, the process of note-writing at the study institution can vary by provider/clinician. As such, there were instances of missing information owing to a lack of medical record documentation (which was not in the control of the chart reviewers).

In Round 2 analysis (8–17 years), there were a total of 139 unique patients (children) who visited the ED at the study institution for asthma between January 2019 and June 2020. A retrospective review of each individual record over an 18-month timeframe revealed that 96 (69%) were “one-time ED” patients, whereas 43 (31%) were “repeat ED” patients. It would be relevant to note that although a total of 139 individual records were reviewed, not all contained complete data on every individual demographic and risk factor variable examined. Some of these variables contained missing values, as summarized in

Table 2 for Round 2 analysis.

Contingency table analysis and logistic regression analysis were conducted in both Round 1 and 2. Both rounds of logistic regression analysis included seven key independent variables (IVs):

asthma severity,

age,

gender,

race,

insurance,

BMI, and

socioeconomic risk. Excluding “encounter length of stay” and “encounter type” from the regression model was appropriate, since both these variables could serve as proxies for “asthma severity”. Importantly, restricting the logistic model to seven IVs in both rounds of analysis enabled comparability of the results between rounds and with the earlier (aforementioned) outpatient study, while also ensuring adherence to the statistical convention of 10-plus observations for every included IV in logistic regression, for valid statistical results [

19]. Round 1 results from the contingency table and logistic regression analysis are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively, while Round 2 results from the contingency table and logistic regression analysis are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6, respectively.

5.1. Round 1 Results

Results from Round 1 analysis revealed that although a few variables, including

age,

insurance, and

socioeconomic risk emerged as statistically significant in the contingency table analysis (

Table 3), only

age was statistically significant in the logistic regression model, after adjusting for all other variables. The Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test was 25.94068 (df = 14) with

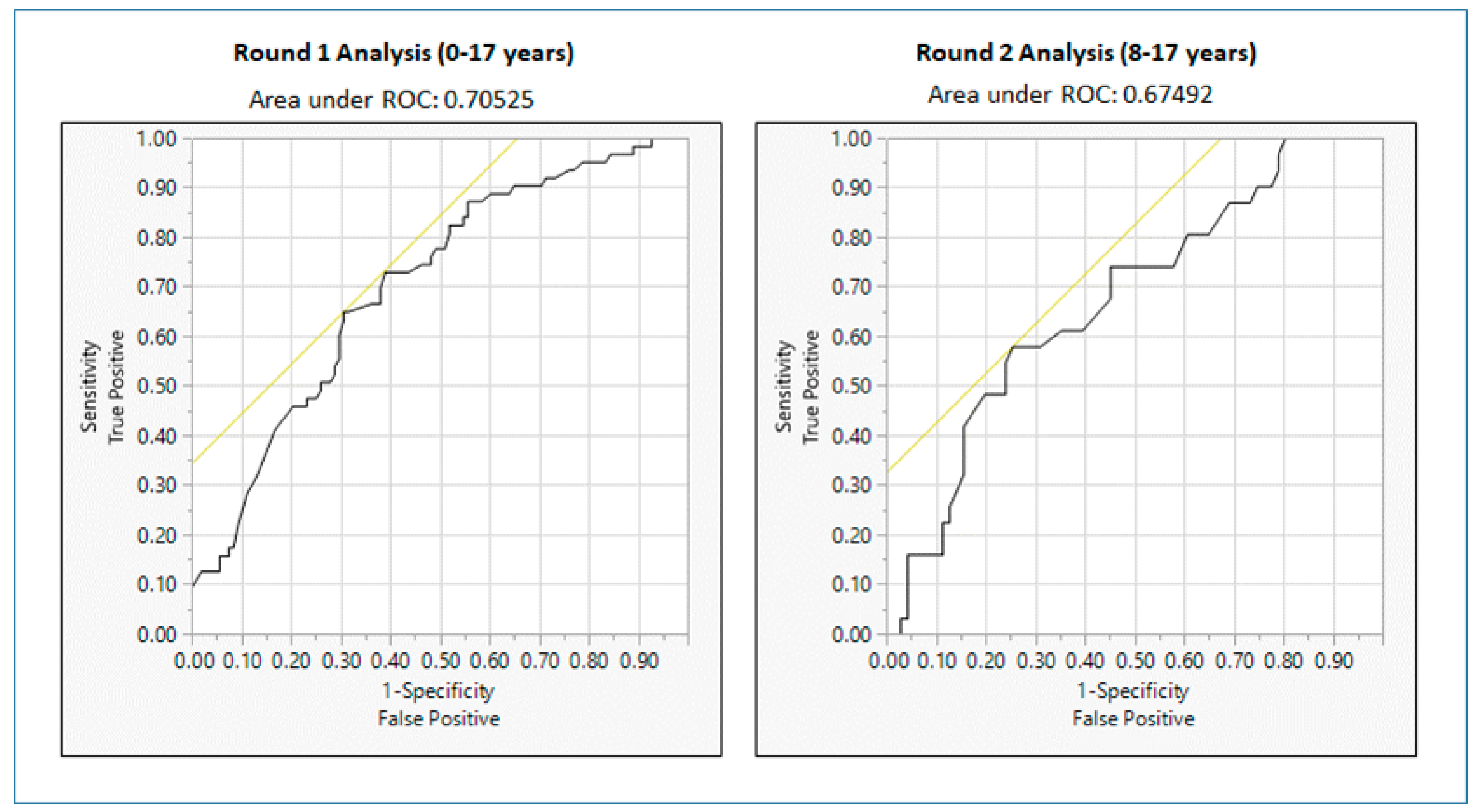

p-value = 0.0263 indicating that the overall logistic regression model is significant. In addition, the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.7053 (greater than 0.50), confirming that the logistic regression model is adequate for this analysis.

Figure 1 shows the ROC curves corresponding to logistic regression models for Round 1 and Round 2 analyses. As indicated in

Table 4 (in the odds ratio section), children 5–9 years of age, were three times more likely than children under <5 years of age to have “repeat” ED visits (i.e., visit the ED more than once over an 18-month period). Other than

age, no variable, including

asthma severity, was significant in predicting “repeat” visits to the ED.

5.2. Round 2 Results

Results from Round 2 analysis were unequivocal in indicating that none of the individual demographic or risk factors examined (not a single one) were significant in predicting “repeat” visits to the ED for childhood asthma, neither in the contingency table analysis (

Table 5) nor in the logistic regression analysis (

Table 6). The Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test was 9.160775 (df = 11) with

p-value = 0.6071, indicating that the overall logistic regression model is not significant. However, the area under the ROC curve is 0.6749 (greater than 0.50), confirming that although the logistic regression model is not significant in this case due to smaller sample size, it is acceptable for this analysis.

6. Discussions

To summarize the results, in Round 1 analysis (0–17 years), except for age, no other individual demographic or risk factor was significant in predicting “repeat” ED visits for childhood asthma. Results showed significantly higher likelihood of “repeat” ED visits in the 5–9 years age-group compared to the <5 years age-group. This could be owing to the fact that children 5–9 years may be more able to articulate their symptoms and concerns to their parents, prompting more ED visits. However, as discussed under Methodology, the potential limitations to the reliability of asthma clinical diagnosis in ages below 8 years (and particularly below 5 years) need to be acknowledged while interpreting this result. The latter concern in turn makes Round 2 results (8–17 years) particularly relevant for verifying Round 1 results and consolidating our understanding of the role of the individual demographic and risk factors examined in predicting “repeat” ED visits. Round 2 results are particularly relevant when the above concern is considered in conjunction with the fact that the 8–17 years age interval has been preferred in primary pediatric research, owing to higher confidence in the ability of children 8 years and older to reliably complete surveys and interviews related to asthma management (with parental consent) [

15,

16]. Importantly, since Round 2 results are based on children ages 8–17 years, they are directly comparable to results from the outpatient study at the same institution. As indicated in

Table 5 and

Table 6, Round 2 results were unequivocal in revealing that not a single one of the individual demographic or risk factors examined was statistically significant in predicting “repeat” ED visits for childhood asthma (neither in contingency table analysis nor the logistic regression analysis).

The outpatient study (described under Background) examined the same age-group as Round 2 of this (ED) study and found that other than

asthma severity, no other individual demographic and risk factor examined was significant in predicting unscheduled healthcare use (including ED visits) for asthma. Moreover,

asthma severity was only found to be significant in explaining the number of users of unscheduled healthcare in the “mild-persistent” category compared to “severe-persistent”. The fact remained that there were users and non-users of unscheduled healthcare in all three persistent asthma severity categories (mild, moderate, and severe) and none of the individual demographic or risk factors examined served to explain differences in the use of unscheduled healthcare across the three severity groups [

11]. A key implication therefore was that something other than the individual factors examined was driving unscheduled healthcare use. These findings in turn served to provide impetus for future research on drivers of unscheduled healthcare use and SME for childhood asthma informed by the “holistic framework”. Round 2 results (for 8–17 years) not only serve to corroborate the results of the outpatient study, but they go a step further in finding that even

asthma severity (defined as intermittent, mild-persistent, moderate-persistent, and severe-persistent asthma) was not significant in predicting “repeat” ED visits for childhood asthma, a result that was also indicated in Round 1 analysis. These findings suggest that the results from this (ED) study are equally, if not more emphatic (than the outpatient study), in providing impetus for future research on understanding the drivers of unscheduled healthcare use and SME of childhood asthma, informed by the “holistic framework”.

Importantly, Round 2 results serve to contribute to the literature on ED utilization for asthma. Although the existing literature has found the biggest determinants of ED utilization for childhood asthma to be access to care, disease severity, and socioeconomic factors, the vast majority of these studies have been undertaken among uninsured children and children with insurance coverage gaps [

12,

13,

14]. The pediatric asthma patient population in this study however is largely insured, with access to primary care for asthma. None of the patients were uninsured. It would also be relevant to note that the existing literature on ED utilization in the insured population has found race and severity to be significant predictors of recurrent ED visits [

1,

2,

3]. This study did not find

asthma severity and other socioeconomic factors like

race and

insurance to be significant predictors of “repeat” ED visits, suggesting that future research may be needed to understand key drivers of “repeat” ED visits and unscheduled healthcare use for childhood asthma in a largely insured population with access to primary and specialty care. In summary, congruent with its intended purpose, this study serves the dual purpose of (

1) providing a foundation for future primary research on measuring and improving childhood asthma SME, and (

2) contributing to the literature on ED utilization for childhood asthma.

6.1. Study Limitations and Strengths

Limitations of this study include reliance on retrospective chart review, which restricts data availability to data contained in the medical record. It would also be relevant to note that there was limited variability in race in the study population, with 87% being African-American. It would be relevant to note however that the outpatient study population (at the same institution) had greater variability in race, with 69% being African-American. In the outpatient study, race was not found to be a significant predictor of unscheduled healthcare use (including ED visits), and in this (ED) study, race was not found to be a significant predictor of repeat ED visits for childhood asthma. Another limitation of this study was missing data for some variables. It would be relevant to note however that despite this limitation, we were left with a healthy sample size of n = 171 for Round 1 logistic regression and n = 102 for Round 2 logistic regression. It must also be acknowledged that patient visits to other EDs in the community may have been missed in the absence of documentation; however, this is less of a concern given that the study is set in a large academic health system providing primary, secondary, and tertiary care, with most of the children (patients of the health system) known to receive all their care within the institution, including emergency visits and hospitalizations.

Key strengths of the study include the use of clinical experts (two medical students and supervising physician for chart review) and an adequate sample size of

n = 252 for Round 1 analysis and

n = 139 for Round 2 analysis, both of which significantly exceed the statistical rule-of-thumb of

n = 30 for statistical significance. The study location may also be viewed as a strength. Augusta, Georgia is located in an area of the southern U.S. that has elevated rates of morbidity and mortality from a variety of chronic diseases, especially asthma. In 2015, Augusta was featured in the “Top Ten Asthma Capitals of the US” by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America [

20]. Our sample of asthma-vulnerable children therefore may be representative of other high-risk rural or inner-city U.S. outpatient settings for asthma treatment. Moreover, the higher asthma severity patient base served by the medical center as a whole is highly relevant to understanding unscheduled healthcare use in child asthma, as echoed by the Pareto Principle on healthcare use: 80% of unscheduled (costly) healthcare use could be attributed to the 20% severely-ill populace [

21].

6.2. Implications for Future Research and Practice

The study provides important implications for future research and practice in childhood asthma management. In both the outpatient study and this ED study, the differences in use of unscheduled healthcare for childhood asthma (including repeat ED visits in this study) were not explained by any of the individual demographic and risk factors examined (after adjusting for asthma severity). A key implication of these results therefore is that other factors (not examined) are at play in driving “repeat” ED visits and unscheduled healthcare use (“low SME”) for childhood asthma. These findings in turn provide the impetus for future primary research on measuring and improving SME of childhood asthma, informed by a “holistic framework”.

Although the NHLBI guidelines have emphasized the importance of provider–patient partnership in improving asthma SME, and systematic reviews have determined that “supported self-management of asthma” can reduce unscheduled healthcare use across a wide variety of populations, the evidence pertaining to the interrelationships among provider–patient/family communication, patient/family activation, and asthma SME remains fragmented. For example, a 2017 study examining the relationship between physician–patient communication and self-care skills for asthma was limited by: (

1) defining self-care skills solely in terms of asthma medication adherence (as opposed to medication adherence, environmental trigger avoidance, and symptom control as a whole); (

2) not considering any health outcome measures, including healthcare use for asthma; (

3) not utilizing validated measures of physician–patient communication; (

4) not accounting for the impact of a variety of socio-ecological influences on self-care skills; and (

5) relying entirely on a retrospective cross-sectional study design [

22].

The fragmented nature of the asthma SME literature in turn mitigates understanding of the specific mechanisms by which “supported self-management of asthma” reduces unscheduled healthcare and strengthens SME, which in turn serves as a barrier to: (i) systematically engaging providers in measuring and improving asthma SME; (ii) identifying holistic interventions for improving and sustaining asthma SME (for future evaluation); and (iii) ensuring consistent implementation of NHLBI guidelines in routine clinical practice.

A full-fledged primary research study for measuring and improving SME of childhood asthma (informed by the “holistic framework”) has the potential to address these gaps in the literature. This type of comprehensive study of factors influencing childhood asthma SME (and unscheduled healthcare use) in turn has the potential to generate resources and tools for asthma providers to measure SME in the clinic setting, and improve SME in real-time, through effective, targeted interventions, in line with NHLBI practice guidelines. In summary, future studies informed by the “holistic framework” have the potential to serve the dual purpose of addressing gaps in the asthma management literature, while tackling the practical challenges of childhood asthma management.

7. Conclusions

This study examined demographic and risk factor differences between children who visited the ED for asthma once (“one-time”) and more than once (“repeat”) over an 18-month retrospective timeframe at an academic medical center. The essential finding of the study is that none of the individual risk factors examined, including age (among 8–17 year olds), race, gender, insurance, and asthma severity, were statistically significant in predicting “repeat” ED visits for childhood asthma. A key implication therefore is that something other than the individual demographic and risk factors examined is driving “repeat” ED visits in children with asthma. The results serve to contribute to the asthma-related ED utilization literature. Importantly, they serve to complement findings from a recent outpatient study (at the same institution) and bolster the impetus for future primary research on measuring and improving SME of childhood asthma. In the longer term, such future research has the potential to alleviate the economic and public health burden of asthma, with implications for managing other chronic diseases.

Author Contributions

The five authors of this paper have contributed to the work reported in the following manner: conceptualization: P.R. and R.M.; investigation: P.R., J.C., N.A., A.P. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation: P.R.; writing—review and editing: P.R., J.C., N.A., A.P. and R.M. All authors have reviewed and approved this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study began following approval from the study site’s Institutional Review Board (IRB-Net ID: 1587371-3).

Informed Consent Statement

A waiver of informed consent for retrospective chart review was granted by the IRB.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified data analyzed in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The dataset contains patient-level data that could be identifiable by combining data elements. Therefore, the data are not publicly available due to concerns associated with data privacy & confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kathleen R. May, Division Chief of Allergy-Immunology and Pediatric Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, for providing expertise and feedback to the authors during the course of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson, L.H.; Chambers, P.; Dexheimer, J.W. Asthma-related emergency department use: Current perspectives. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2016, 8, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma self-management education and environmental management: Approaches to enhancing reimbursement; National Asthma Control Program, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Inserro, A. CDC Study Puts Economic Burden of Asthma at More Than $80 Billion per Year. 2018. Available online: https://www.ajmc.com/view/cdc-study-puts-economic-burden-of-asthma-at-more-than-80-billion-per-year (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- National Institutes of Health National Asthma Education & Prevention Program. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel Report 3; United States Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock, H.; Parke, H.L.; Panagioti, M.; Daines, L.; Pearce, G.; Epiphaniou, E.; Bower, P.; Sheikh, A.; Griffiths, C.J.; Taylor, S.J.C.; et al. Systematic meta-review of supported self-management for asthma: A healthcare perspective. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnock, H.; Epiphaniou, E.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.; Greenhalgh, T.; Sheikh, A.; Griffiths, C.J.; Taylor, S.J.C. Implementing supported self-management for asthma: A systematic review and suggested hierarchy of evidence of implementation studies. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnock, H. Supported self-management for asthma. Breathe 2015, 11, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnock, H.; Thomas, M. Does self-management prevent severe exacerbations? Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2015, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangachari, P. A framework for measuring self-management effectiveness and healthcare use among pediatric asthma patients & families. J Asthma Allergy 2017, 10, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rangachari, P.; May, K.R.; Stepleman, L.M.; Tingen, M.S.; Looney, S.; Liang, Y.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Rethemeyer, R.K. Measurement of Key Constructs in a Holistic Framework for Assessing Self-Management Effectiveness of Pediatric Asthma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangachari, P.; Griffin, D.D.; Ghosh, S.; May, K.R. Demographic and Risk-Factor Differences between Users and Non-Users of Unscheduled Healthcare among Pediatric Outpatients with Persistent Asthma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oraka, E.; Iqbal, S.; Flanders, W.D.; Brinker, K.; Garbe, P. Racial and ethnic disparities in current asthma and emergency department visits: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 2001-2010. J. Asthma 2013, 50, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.S.; Carrión-Carire, V.; Weiss, K.B. The widening black/white gap in asthma hospitalizations and mortality. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gushue, C.; Miller, R.; Sheikh, S.; Allen, E.D.; Tobias, J.D.; Hayes, D., Jr.; Tumin, D. Gaps in health insurance coverage and emergency department use among children with asthma. J. Asthma 2018, 56, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, A.L.; Crouch, E. The Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Anxiety and Depression for Children and Youth, 8 to 17 Years of Age. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, J.C.; Latour, J.M.; Curley, M.A.Q.; Draper, E.S.; Jilani, T.; Quinlan, P.R.; Watson, R.S.; Rennick, J.E.; Colville, G.; Pinto, N.; et al. Study protocol for a multicentre longitudinal mixed methods study to explore the Outcomes of Children and families in the first year after paediatric Intensive Care: The OCEANIC study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society (ATS). Official Documents for Pulmonary Function Testing. Available online: https://www.thoracic.org/statements/pulmonary-function.php (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Jat, K.R. Spirometry in children. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2013, 22, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’At, N.; Sidik, T.M.I.T.A.B.; Joo, L.C. Sample Size Guidelines for Logistic Regression from Observational Studies with Large Population: Emphasis on the Accuracy Between Statistics and Parameters Based on Real Life Clinical Data. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. Asthma Capitals: Top 100 National Ranking. Available online: https://www.aafa.org/asthma-capitals-top-100-cities-ranking/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Fetherling, J.T. Vilfredo Pareto’s 80/20 Hypothesis Applies to Healthcare. 2016. Available online: https://www.perceptionhealth.com/research/80-20-pareto-lives-in-healthcare (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Young, H.N.; Len-Rios, M.E.; Brown, R.; Moreno, M.A.; Cox, E.D. How does patient-provider communication influence adherence to asthma medications? Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).