Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Generative Acts among Chinese Grandparents

1.2. Instruments to Measure Generative Acts

1.3. Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

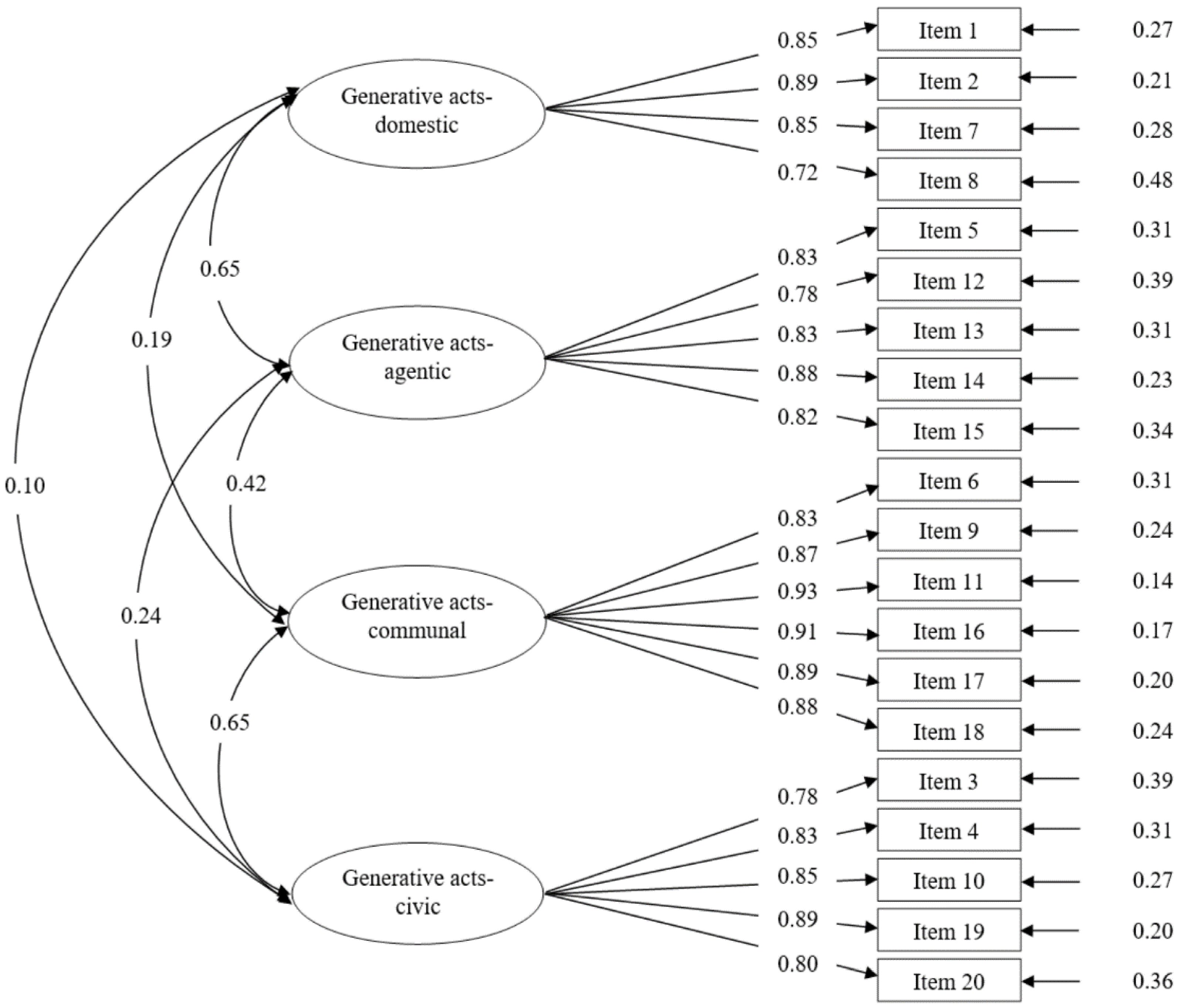

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Measurement Invariance

3.4. Reliability Estimation

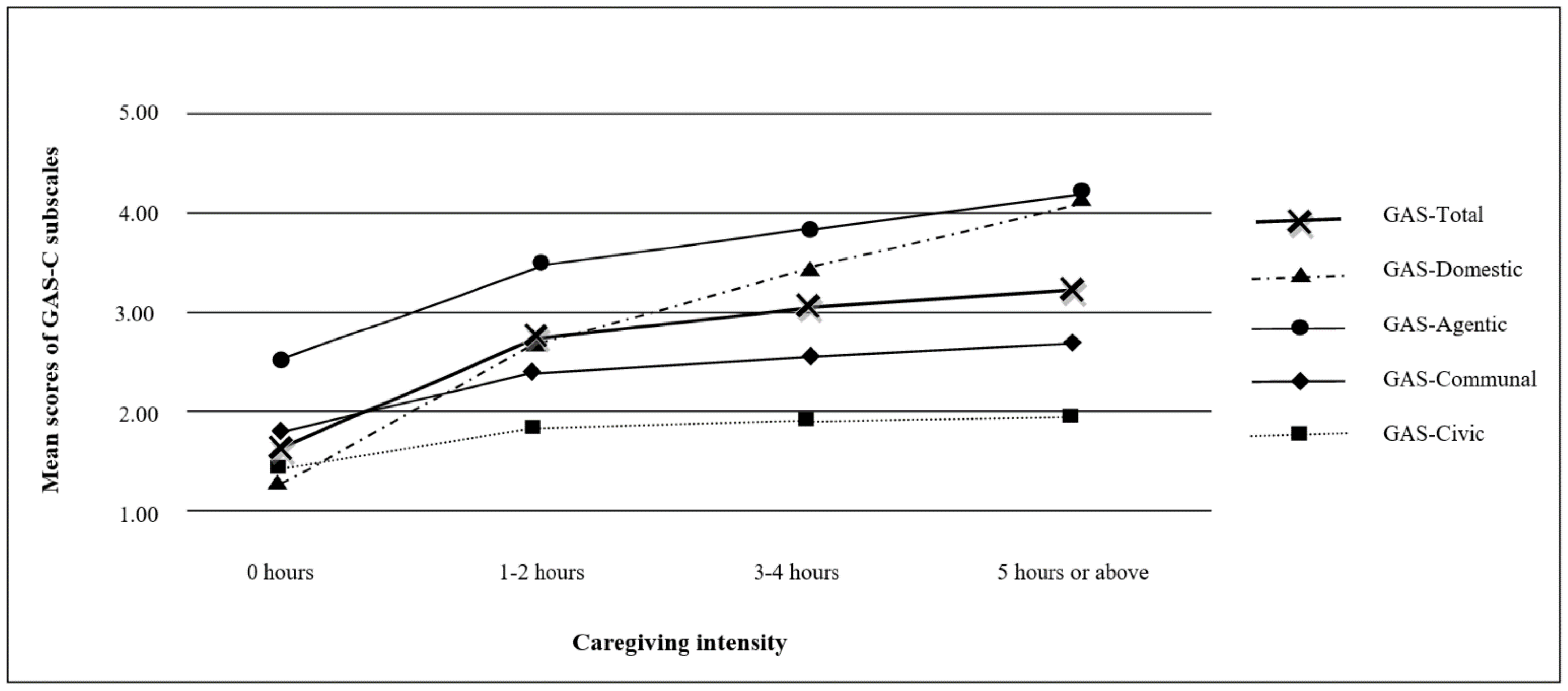

3.5. Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society, 2nd ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P.; de St. Aubin, E. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, D.M.; Whelan, T.A. The relationship between grandparent satisfaction, meaning, and generativity. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 66, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noriega, C.; Velasco, C.; López, J. Perceptions of grandparents’ generativity and personal growth in supplementary care providers of middle-aged grandchildren. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 37, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlomo, S.B.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. Grandparenthood—Grand Generativity. In Grandparents of Children with Disabilities: Theoretical Perspectives of Intergenerational Relationships; Briefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, F.; Celdrán, M.; Triado, C. Grandmothers offering regular auxiliary care for their grandchildren: An expression of generativity in later life? J. Women Aging 2012, 24, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, C.; Lopez, J.; Velasco, C.; Yolpant, W. Determinants of grandparents’ psychological well-being-generativity and adult children’s gratitude. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, S.M.; Cha, S.E.; Choi, Y.H.; Jung, Y.K. Effects of grandparenting roles and generativity on depression among grandmothers providing care for grandchildren. Korean J. Community Living Sci. 2015, 26, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, S.; Timonen, V. Contemporary Grandparenting: Changing Family Relationships in Global Contexts; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Liu, G.; Mair, C.A. Intergenerational Ties in Context: Grandparents Caring for Grandchildren in China. Soc. Forces 2011, 90, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chi, I. Determinants of support exchange between grandparents and grandchildren in rural China: The roles of grandparent caregiving, patrilineal heritage, and emotional bonds. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, P.C.; Hank, K. Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China and Korea: Findings from CHARLS and KLoSA. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, F.; Jiang, M.; Hesketh, T. Care for left-behind children in rural China: A realist evaluation of a community-based intervention. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. Migrating (grand) parents, intergenerational relationships and neo-familism in China. J. Comp. Soc. Work 2018, 13, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Dong, X.-Y. Women’s employment and child care choices in urban China during the economic transition. Econ. Devel. Cult. Chang. 2013, 62, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X. Floating grandparents: Rethinking family obligation and intergenerational support. Int. Sociol. 2018, 33, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. Bringing children to the cities: Gendered migrant parenting and the family dynamics of rural-urban migrants in China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 46, 1460–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Keene, D.E.; Monin, J.K. “Their happiness is my happiness”—Chinese visiting grandparents grandparenting in the US. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2019, 17, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tang, F.Y.; Li, L.W.; Dong, X.Q. Grandparent caregiving and psychological well-being among Chinese American older adults-The roles of caregiving burden and pressure. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, S56–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Hart, H.M.; Maruna, S. The Anatomy of Generativity. In Generativity and Adult Development: How and Why We Care for the Next Generation; McAdams, D.P., de St. Aubin, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 7–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.T. Generativity in later life: Perceived respect from younger generations as a determinant of goal disengagement and psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.C.-M.; Cao, T. Age-friendly neighbourhoods as civic participation: Implementation of an active ageing policy in Hong Kong. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2015, 29, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, D.; Sun, J.; Sun, F. A comparative review of grandparent care of children in the US and China. Ageing Int. 2013, 38, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Emery, T.; Dykstra, P. Grandparenthood in China and Western Europe: An analysis of CHARLS and SHARE. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 45, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M.R.; Gruenewald, T.L. Caregiving and perceived generativity: A positive and protective aspect of providing care? Clin. Gerontol. 2017, 40, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gessa, G.; Glaser, K.; Price, D.; Ribe, E.; Tinker, A. What drives national differences in intensive grandparental childcare in Europe? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhu, D. Subjective well-being of Chinese landless peasants in relatively developed regions: Measurement using PANAS and SWLS. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 123, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.R. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Cao, C.; Wang, Y.; Nguyen, D.T. Measurement invariance testing with many groups: A comparison of five approaches. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2017, 24, 524–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Aggen, S.; Shi, S.; Gao, J.; Tao, M.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. The structure of the symptoms of major depression: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in depressed Han Chinese women. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kotre, J. Outliving the Self: Generativity and the Interpretation of Lives; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, F.; Serrat, R. A field in search of concepts: The relevance of generativity to understanding intergenerational relationships. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2014, 12, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, F. Successful ageing and development: The contribution of generativity in older age. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arber, S.; Ginn, J. Gender differences in informal caring. Health Soc. Care Community 1995, 3, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoklitsch, A.; Baumann, U. Measuring generativity in older adults. J. Gerontopsychology Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J.; McLaughlin, D.; Pinsker, D. Generative acts: Family and community involvement of older Australians. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2006, 63, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.; Ryff, C. Generativity in Adult Lives: Social Structural Contours and Quality of Life Consequences. In Generativity and Adult Development: How and Why We Care for the Next Generation; McAdams, D.P., de St. Aubin, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 227–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, G.P.; Yardley, J.E.; Martineau, L.; Jay, O. Physical work capacity in older adults: Implications for the aging worker. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2008, 51, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoklitsch, A.; Baumann, U. Generativity and aging: A promising future research topic? J. Aging Stud. 2012, 26, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, K.-F. The Marriage Institution in Hong Kong: Past and Present. In Handbook on the Family and Marriage in China; Zang, X., Zhao, L.X., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. Intergenerational intimacy and descending familism in rural North China. Am. Anthr. 2016, 118, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.S. Solidarity, Ambivalence and Multigenerational Co-Residence in Hong Kong. In Contemporary Grandparenting: Changing Family Relationships in Global Contexts; Arber, S., Timonen, V., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Wang, M.P.; Ho, H.C.; Wan, A.; Stewart, S.M.; Viswanath, K.; Chan, S.S.C.; Lam, T.H. Test–retest reliability and validity of a single-item self-reported family happiness scale in Hong Kong Chinese: Findings from Hong Kong Jockey Club FAMILY project. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | F 1 | F2 | F 3 | F 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I take care of children and grandchildren when they are ill. | 0.837 1 | 0.029 | −0.001 | 0.051 |

| 2. Taking care of my offspring’s daily life, including preparing meals. | 0.977 | −0.051 | 0.006 | −0.027 |

| 7. Take care of the grandchildren when their parents are not available. | 0.792 | 0.077 | 0.007 | −0.029 |

| 8. Do housework for my children. | 0.676 | 0.056 | −0.008 | 0.023 |

| 5. Be a role model to the next generation. | 0.252 | 0.673 | −0.010 | −0.016 |

| 12. Share my past experience, whether bitter or sweet, with the next generation. | 0.055 | 0.721 | 0.009 | −0.022 |

| 13. Teach the next generation not to spend money on unnecessary items. | −0.041 | 0.869 | −0.057 | −0.003 |

| 14. Teach the next generation to know right from wrong, and to observe rules and regulations. | −0.040 | 0.943 | −0.041 | 0.001 |

| 15. Pass on my skills and talents to the next generation. | 0.049 | 0.686 | 0.134 | 0.033 |

| 6. Learn new things so as to make myself useful to the younger generations. | 0.024 | −0.035 | 0.806 | 0.042 |

| 9. Teach the younger generations how to get along with others and handle various matters. | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.878 | −0.033 |

| 11. Take initiative to comfort young people in distress. | 0.012 | −0.009 | 0.925 | −0.043 |

| 16. Counsel younger people who are emotionally disturbed. | −0.020 | −0.015 | 0.935 | −0.042 |

| 17. Encourage the younger generations to learn new things and develop multiple interests. | −0.032 | 0.028 | 0.870 | 0.011 |

| 18. Teach younger generations to do voluntary work and to serve others. | 0.030 | −0.042 | 0.802 | 0.129 |

| 3. Participate in volunteer work and continue to serve the community. | 0.068 | −0.045 | −0.053 | 0.839 |

| 4. Visit other people in need, like patients. | 0.049 | −0.092 | −0.044 | 0.887 |

| 10. Participate in community educational activities. | −0.026 | 0.026 | −0.013 | 0.861 |

| 19. Give a hand to needy people in the community. | −0.045 | 0.027 | 0.098 | 0.808 |

| 20. Do something that benefits others. | −0.067 | 0.129 | 0.120 | 0.620 |

| Gender | Age | Hukou | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 285) | Female (n = 728) | Middle-Aged (n = 591) | Older Adults (n = 422) | Local (n = 508) | Migrant (n = 505) | |

| Chi-square | 411.739 | 767.230 | 694.756 | 557.346 | 595.253 | 580.713 |

| Degrees of freedom | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CFI | 0.945 | 0.951 | 0.946 | 0.948 | 0.949 | 0.953 |

| RMSEA | 0.077 | 0.071 | 0.074 | 0.075 | 0.072 | 0.071 |

| SRMR | 0.047 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.043 |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By gender | |||||||||

| Configural invariance | 1208.969 | 328 | 0.949 | 0.073 | |||||

| Metric invariance | 1224.783 | 344 | 0.949 | 0.071 | 15.814 | 16 | 0.466 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Scalar invariance | 1260.643 | 360 | 0.948 | 0.070 | 51.674 | 32 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| By age | |||||||||

| Configural invariance | 1252.102 | 328 | 0.947 | 0.075 | |||||

| Metric invariance | 1275.059 | 344 | 0.946 | 0.073 | 22.957 | 16 | 0.115 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Scalar invariance | 1294.245 | 360 | 0.946 | 0.072 | 42.143 | 32 | 0.108 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| By hukou | |||||||||

| Configural invariance | 1175.966 | 328 | 0.951 | 0.071 | |||||

| Metric invariance | 1231.173 | 344 | 0.949 | 0.071 | 55.207 | 16 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Scalar invariance | 1317.323 | 360 | 0.945 | 0.072 | 141.357 | 32 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| Subscales | Items | M | SD | Corrected Item-Dimension Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha of Subscales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative acts-domestic | Item 1 | 3.578 | 1.147 | 0.794 | 0.897 |

| Item 2 | 3.698 | 1.215 | 0.847 | ||

| Item 7 | 3.978 | 1.131 | 0.786 | ||

| Item 8 | 3.445 | 1.329 | 0.679 | ||

| Generative acts-agentic | Item 5 | 4.019 | 1.006 | 0.781 | 0.909 |

| Item 12 | 3.769 | 1.102 | 0.742 | ||

| Item 13 | 4.086 | 0.976 | 0.772 | ||

| Item 14 | 4.186 | 0.946 | 0.828 | ||

| Item 15 | 3.738 | 1.184 | 0.758 | ||

| Generative acts-communal | Item 6 | 2.499 | 1.046 | 0.807 | 0.953 |

| Item 9 | 2.688 | 1.086 | 0.854 | ||

| Item 11 | 2.720 | 1.082 | 0.884 | ||

| Item 16 | 2.601 | 1.094 | 0.876 | ||

| Item 17 | 2.763 | 1.129 | 0.864 | ||

| Item 18 | 2.604 | 1.159 | 0.846 | ||

| Generative acts-civic | Item 3 | 1.696 | 0.917 | 0.746 | 0.912 |

| Item 4 | 1.651 | 0.888 | 0.792 | ||

| Item 10 | 2.015 | 1.072 | 0.812 | ||

| Item 19 | 1.956 | 1.034 | 0.832 | ||

| Item 20 | 2.350 | 1.068 | 0.715 |

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | Range | F (1, 1011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (total) | 285 | 3.113 | 0.714 | 1–5 | 2.950 |

| Female (total) | 728 | 3.030 | 0.678 | 1–5 | |

| Domestic (subtotal) | 1013 | 3.675 | 1.056 | 1–5 | 4.322 * |

| Male | 285 | 3.565 | 1.036 | 1–5 | |

| Female | 728 | 3.718 | 1.061 | 1–5 | |

| Agentic (subtotal) | 1013 | 3.960 | 0.897 | 1–5 | 0.402 |

| Male | 285 | 3.988 | 0.817 | 1–5 | |

| Female | 728 | 3.948 | 0.926 | 1–5 | |

| Communal (subtotal) | 1013 | 2.646 | 0.990 | 1–5 | 8.001 ** |

| Male | 285 | 2.786 | 1.073 | 1–5 | |

| Female | 728 | 2.591 | 0.951 | 1–5 | |

| Civic (subtotal) | 1013 | 1.934 | 0.859 | 1–5 | 17.474 *** |

| Male | 285 | 2.112 | 0.941 | 1–5 | |

| Female | 728 | 1.864 | 0.814 | 1–5 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. GAS-Total | 3.053 | 0.689 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. GAS-Domestic | 3.675 | 1.056 | 0.707 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. GAS-Agentic | 3.960 | 0.897 | 0.780 ** | 0.626 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. GAS-Communal | 2.646 | 0.990 | 0.762 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.408 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. GAS-Civic | 1.933 | 0.859 | 0.647 ** | 0.133 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.594 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Positive affect | 3.058 | 0.712 | 0.397 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.335 ** | 0.299 ** | 1 | |

| 7. Life satisfaction | 3.448 | 0.915 | 0.328 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.445 ** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Ngai, S.S.-y. Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199950

Guo H, Ngai SS-y. Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):9950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199950

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Haoyi, and Steven Sek-yum Ngai. 2021. "Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 9950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199950

APA StyleGuo, H., & Ngai, S. S.-y. (2021). Validation of the Generative Acts Scale-Chinese Version (GAS-C) among Middle-Aged and Older Adults as Grandparents in Mainland China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 9950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199950