Dementia in Media Coverage: A Comparative Analysis of Two Online Newspapers across Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Online vs. Print Newspapers

3. Dementia and Discourse of Dementia

4. Brief Review of Relevant Literature

For many lay people, the mass media constitute one of the most important sources of information about health and medicine. Mass media portrayals contribute to the creation or reproduction of knowledges about illness and disease … they work to portray ill people in certain lights (for example, as ‘innocent victims’ or ‘deserving of their fate’).

5. Theoretical Considerations

6. Current Study

7. Study Aim and Research Questions

- Are there changes in news content related to dementia in the NYT and the GDN over time?

- What are the differences in news stories between the NYT and the GDN across time?

- What is the overall tone in presenting topics related to dementia both in the NYT and the GDN?

8. Materials and Methods

8.1. Data Sources

- (1)

- The New York Times (https://www.nytimes.com/) (accessed on 11 December 2019). The online version of the newspaper was established in 1996. As of December 2019, the approximate daily average page viewers (readership) for this newspaper was 11.46 million per day.

- (2)

- The Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/) (accessed on 11 December 2019). This newspaper launched the online version in 1995. As of December 2019, the approximate daily average page viewers (readership) for this newspaper were 8.74 million per day.

8.2. Selection of News Coverage

8.3. Article Search and Manual Exclusion

8.4. Constructing the Coding Design

8.4.1. Title Focus

8.4.2. News Section

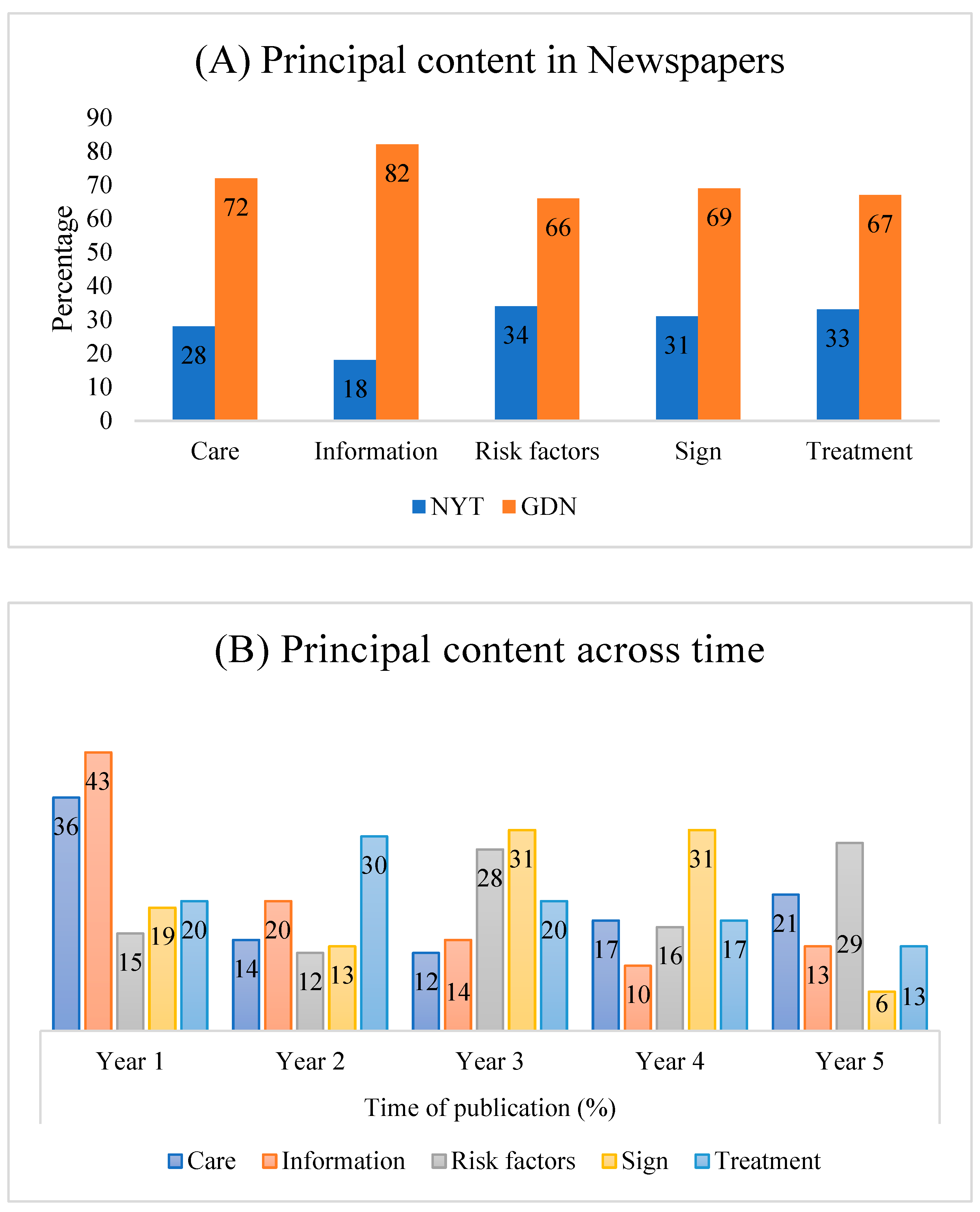

8.4.3. Principal Content

8.4.4. News Story Category

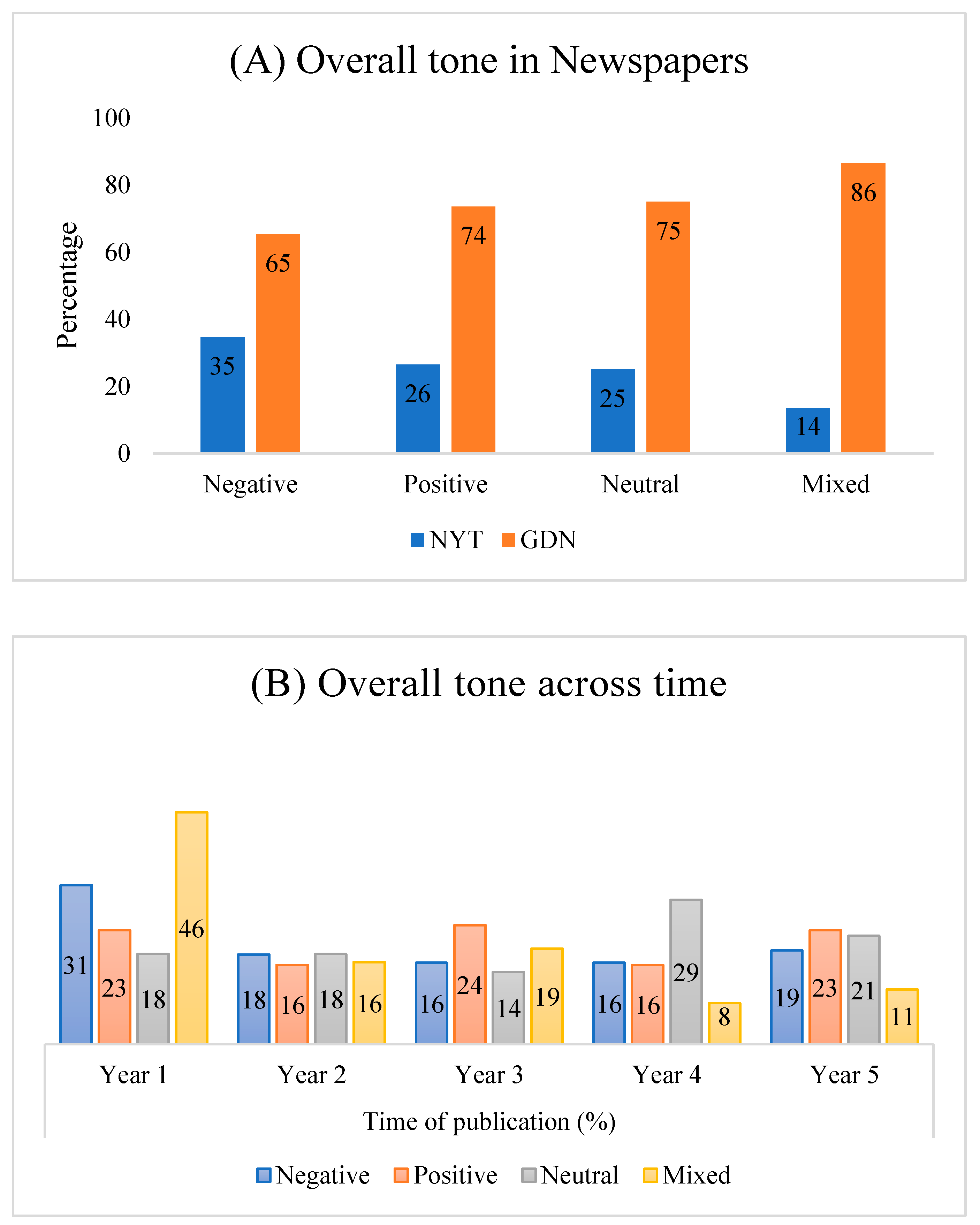

8.4.5. Overall Tone

8.5. Inter-Rater Reliability

8.6. Statistical Analyses

8.7. Ethical Considerations

9. Results

9.1. Principal Content

9.2. Story Category

9.3. Overall Tone

9.4. Representation of Dementia in Newspapers

10. Discussion

11. Potential Implications

12. Limitations

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PlwD | People living with dementia |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| GDN | Guardian Newspaper |

| NYT | New York Times |

Appendix A. Coding Instrument

| Title focus | Coding scheme | |

| Does the news title focus on illness/dementia? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the news title focus on person (diagnosed/caregiver)? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Principal content | ||

| Does the news content deal with care issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| (Care refers to: Formal care, Informal care, Social Care, Self-care) | ||

| Does the news content deal with information issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| (Information refers to: Attitudes, Awareness, Financial, Policy) | ||

| Does the news content deal with risk factor issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| (Risk factor refers to: Modifiable risks, Non-modifiable risks) | ||

| Does the news content deal with sign issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| (Sign refers to: Early stage, Late stage) | ||

| Does the news content deal with treatment issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| (Treatment refers to: Biomedical, Technological) | ||

| News story category | ||

| Does the story deal with burden issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the story deal with knowledge issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the story deal with prevalence issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the story deal with prevention issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Overall tone | ||

| Does the news indicate negative issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the news indicate positive issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the news indicate neutral issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| Does the news indicate mixed issues? | No (0) | Yes (1) |

References

- Higgs, P.; Gilleard, C. Ageing, dementia and the social mind: Past, present and future perspectives. Sociol. Health Illn. 2017, 39, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, A.M. Dementia in the news: The media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australas. J. Ageing 2006, 25, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.N. The case of the missing person: Alzheimer’s disease in mass print magazines 1991–2001. Health Commun. 2006, 19, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.; Doyle, C. Dementia policy in Australia and the ‘social construction’ of infirm old age. Health Hist. 2014, 16, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, H.; Gilhooly, M. Dementia and the phenomenon of social death. Sociol. Health Illn. 1997, 19, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siiner, M. Let me grow old and senile in peace: Norwegian newspaper accounts of voice and agency with dementia. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.; Dening, T.; Harvey, K. Battles and breakthroughs: Representations of dementia in the British press. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, M.; Augoustinos, M. Brain health advice in the news: Managing notions of individual responsibility in media discourse on cognitive decline and dementia. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2017, 14, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.C. Thinking Through Dementia; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg, D.I.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Dementia: A word to be forgotten. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fealy, G.; McNamara, M.; Treacy, M.P.; Lyons, I. Constructing ageing and age identities: A case study of newspaper discourses. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šestáková, A.; Plichtová, J. More than a medical condition: Qualitative analysis of media representations of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Aff. 2020, 30, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, E. The living death of Alzheimer’s versus Take a walk to keep dementia at bay: Representations of dementia in print media and carer discourse. Sociol. Health Illn. 2014, 36, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeilig, H. Dementia as a cultural metaphor. Gerontol. 2014, 54, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, N. Newspaper Consumption in the Mobile Age: Re-assessing multi-platform performance and market share using “time-spent”. Journal. Stud. 2018, 19, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newspaper Circulation Revenue Worldwide from 2012 to 2017, by Platform. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/260204/distribution-of-newspaper-revenue-worldwide-by-platform/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Bamford, S.; Holley-Moore, G.; Watson, J. New Perspectives and Approaches to Understanding Dementia and Stigma; ILC-UK: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunati, L.; Taipale, S.; Farinosi, M. Print and online newspapers as material artefacts. Journalism 2015, 16, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundal, P.; Mishra, R. Print and online newspapers: An analysis of the news content and consumption patterns of readers. J. Indian Inst. Mass Commun. 2018, 53, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Assumpção, M.; Alfinito, S.; Castro, B.G.A. Newspaper Consumption in Print and Online: Printed Newspapers is Status and Online is Easiness. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2019, 23, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyi, H.I.; Lee, A.M. Online news consumption: A structural model linking preference, use, and paying intent. Digit. J. 2013, 1, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.L.; Webster, J.G. The myth of partisan selective exposure: A portrait of the online political news audience. Soc. Media Soc. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, A. The media coverage of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related conditions. Alzheimers News Natl. Newsl. Alzheimers N. Z. Inc. 2003, 54, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hydén, L.-C.; Lindemann, H.; Brockmeier, J. Beyond Loss: Dementia, Identity, Personhood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- sm-Rahman, A.; Lo, C.H.; Ramic, A.; Jahan, Y. Home-based care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) during COVID-19 pandemic: From challenges to solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Borin, G. Understanding dementia in the sociocultural context: A review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calia, C.; Johnson, H.; Cristea, M. Cross-cultural representations of dementia: An exploratory study. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 001–011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, F. Dementia discourse–A rethink? Dementia 2017, 16, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.J.; Dupuis, S.L.; Kontos, P. Dementia discourse: From imposed suffering to knowing other-wise. J. Appl. Hermeneut. 2013, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D. Health, illness and medicine in the media. Health 1999, 3, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.C. Examining media representations: Benefits for health psychology. J. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Werner, P.; Richardson, A.; Anstey, K.J. Dementia stigma reduction (deserve): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of an online intervention program to reduce dementia-related public stigma. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019, 14, 100351–100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gorp, B.; Vercruysse, T. Frames and counter-frames giving meaning to dementia: A framing analysis of media content. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, H.P.; McLachlan, S.; Philip, J. The war against dementia: Are we battle weary yet? Age Ageing 2013, 42, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Faure-Delage, A.; Mouanga, A.M.; M’Belesso, P.; Tabo, A.; Bandzouzi, B.; Dubreuil, C.-M.; Preux, P.-M.; Clément, J.-P.; Nubukpo, P. Socio-cultural perceptions and representations of dementia in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: The EDAC Survey. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2012, 2, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, Y.K.; Levkoff, S.E. Culture and dementia: Accounts by family caregivers and health professionals for dementia-affected elders in South Korea. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2001, 16, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, A. Experience and its moral modes: Culture, human conditions, and disorder. Tann. Lect. Hum. Values 1999, 20, 355–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Jahan, Y. Defining a ‘risk group’ and ageism in the era of COVID-19. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia: A Public Health Priority. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_executivesummary.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Swinnen, A.; Schweda, M. Popularizing Dementia: Public Expressions and Representations of Forgetfulness, Volume 6; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, S.; Pierce, M.; Werner, P.; Darley, A.; Bobersky, A. A systematic review of the public’s knowledge and understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2015, 29, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.; Wu, Y.; Prina, M. The global impact of dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. World Alzheimer Rep. 2015, 2015, 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer, D.G.; Yaffe, K.; Liverman, C.T. Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Gearhart, S.; Bae, H.-S. Coverage of Alzheimer’s disease from 1984 to 2008 in television news and information talk shows in the United States: An analysis of news framing. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2010, 25, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Bonevski, B.; Jones, A.; Henry, D. Media reporting of health interventions: Signs of improvement, but major problems persist. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4831–e4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L. Living with television: The violence profile. J. Commun. 1976, 26, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.; Valenzuela, S. Agenda-setting theory: The frontier research questions. In Estados Unidos: Oxford Handbooks Online; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.J. Agenda Setting in a 2.0 World: New Agendas in Communication; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noelle-Neumann, E. The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. J. Commun. 1974, 24, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K.N.; Rainie, H.; Lu, W.; Dwyer, M.; Shin, I.; Purcell, K. Social Media and The Spiral of Silence’; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alitavoli, R.; Kaveh, E. The US media’s effect on public’s crime expectations: A cycle of cultivation and agenda-setting theory. Societies 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffres, L.W.; Neuendorf, K.; Bracken, C.C.; Atkin, D. Integrating theoretical traditions in media effects: Using third-person effects to link agenda-setting and cultivation. Mass Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; McElvany, N.; Kortenbruck, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Hydén, L.-C. Global Reach of Conceptual Models Used in Ageism and Dementia Studies: A Scoping Review. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-F.; Purwaningrum, F. Negative stereotypes, fear and social distance: A systematic review of depictions of dementia in popular culture in the context of stigma. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S.; Hunt, K.; Langan, M.; Bedford, H.; Petticrew, M. Newsprint media representations of the introduction of the HPV vaccination programme for cervical cancer prevention in the UK (2005–2008). Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bawab, A.Q.; AlQahtani, F.; McElnay, J. Health care apps reported in newspapers: Content analysis. JMIR mHEALTH uHEALTH 2018, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckton, C.H.; Patterson, C.; Hyseni, L.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; Elliott-Green, A.; Capewell, S.; Hilton, S. The palatability of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: A content analysis of newspaper coverage of the UK sugar debate. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nimegeer, A.; Patterson, C.; Hilton, S. Media framing of childhood obesity: A content analysis of UK newspapers from 1996 to 2014. BMJ Open 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, R.V.; Funk, L.M.; Dale, S. Stories of violence and dementia in mainstream news media: Applying a citizenship perspective. Dementia 2020, 20, 2077–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, J.R. Media content analysis: Its uses, benefits and best practice methodology. Asia Pac. Public Relat. J. 2005, 6, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aragonès, E.; López-Muntaner, J.; Ceruelo, S.; Basora, J. Reinforcing stigmatization: Coverage of mental illness in Spanish newspapers. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinty, E.E.; Webster, D.W.; Jarlenski, M.; Barry, C.L. News media framing of serious mental illness and gun violence in the United States, 1997–2012. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, P.; Schiffman, I.K.; David, D.; Abojabel, H. Newspaper Coverage of Alzheimer’s Disease: Comparing Online Newspapers in Hebrew and Arabic across Time. Dementia 2019, 18, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebowitz, M.S.; Ahn, W.-K. Using personification and agency reorientation to reduce mental-health clinicians’ stigmatizing attitudes toward patients. Stigma Health 2016, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/action_plan_2017_2025/en/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-F.; McGrath, M.; Swaffer, K.; Brodaty, H. Communicating a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic mixed studies review of attitudes and practices of health practitioners. Dementia 2019, 18, 2856–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L.; Swaffer, K.; Phillipson, L.; Fleming, R. Questioning segregation of people living with dementia in Australia: An international human rights approach to care homes. Laws 2019, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhana, K.; Evans, D.A.; Rajan, K.B.; Bennett, D.A.; Morris, M.C. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia: Findings from 2 longitudinal studies. Neurology 2020, 95, e374–e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowdell, F. Care of older people with dementia in an acute hospital setting. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 24, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Tanaka, T.; Okochi, M.; Kazui, H. Non-pharmacological intervention for dementia patients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, M.; Snyder, H.M.; Carrillo, M.C.; Fazio, S.; Kim, H.; Johns, H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaffe, K. Modifiable risk factors and prevention of dementia: What is the latest evidence? JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescosolido, B.A.; Martin, J.K.; Lang, A.; Olafsdottir, S. Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A framework integrating normative influences on stigma (FINIS). Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-T. Dementia caregiver burden: A research update and critical analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NYT n(%) | GDN n(%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total | |

| Published articles | 16(20) | 19(23) | 11(13) | 14(17) | 22(27) | 82(28) | 68(33) | 30(14) | 44(21) | 33(16) | 34(16) | 209(72) |

| Title Focus | ||||||||||||

| Dementia | 16(100) | 17(89) | 11(100) | 11(79) | 19(86) | 74(90) | 46(68) | 19(63) | 31(70) | 21(64) | 22(65) | 139(67) |

| Person * | 0(0) | 2(11) | 0(0) | 3(21) | 3(14) | 8(10) | 22(32) | 11(37) | 13(30) | 12(36) | 12(35) | 70(33) |

| News Section | ||||||||||||

| Culture | 1(6) | 1(5) | 0(0) | 2(14) | 0(0) | 4(5) | 8(12) | 7(23) | 0(0) | 1(3) | 1(3) | 17(8) |

| Lifestyle | 9(56) | 14(74) | 8(73) | 7(50) | 16(73) | 54(66) | 11(16) | 1(3) | 6(14) | 6(18) | 3(9) | 27(13) |

| News | 4(25) | 3(16) | 3(27) | 3(21) | 5(23) | 18(22) | 39(57) | 20(67) | 34(77) | 19(58) | 26(76) | 138(66) |

| Opinion | 2(13) | 1(5) | 0(0) | 2(14) | 1(5) | 6(7) | 10(15) | 2(7) | 4(9) | 7(21) | 4(12) | 27(13) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

sm-Rahman, A.; Lo, C.H.; Jahan, Y. Dementia in Media Coverage: A Comparative Analysis of Two Online Newspapers across Time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910539

sm-Rahman A, Lo CH, Jahan Y. Dementia in Media Coverage: A Comparative Analysis of Two Online Newspapers across Time. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910539

Chicago/Turabian Stylesm-Rahman, Atiqur, Chih Hung Lo, and Yasmin Jahan. 2021. "Dementia in Media Coverage: A Comparative Analysis of Two Online Newspapers across Time" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910539

APA Stylesm-Rahman, A., Lo, C. H., & Jahan, Y. (2021). Dementia in Media Coverage: A Comparative Analysis of Two Online Newspapers across Time. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910539