Civil Servants and Non-Western Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Health Care in Serbia—A Grounded Theory, Multi-Perspective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Interviews

2.1.1. Ethical Approvals and Informed Consent

2.1.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.1.3. Data Analysis

2.1.4. Theoretical Integration

3. Results

3.1. Civil Servants’ and Migrants’ Perceptions of Informal Patient Payments

I mean it’s for me I don’t approve it at all. Not before, not after the treatment (…) I think people are pissed off but I think all of them will do that if needed. (Civil Servant 2)

So you have some layers of society who are more powerful than others. Doctors now have power over life and death, like the clergy did before. And just a way to honour this power. So, it is something like a tradition basically. (Civil Servant 1)

This is one of the things where people are talking about cultural you know; I really don’t believe in that because the thing is that this is just a pure bribe. (Civil Servant 3)

(…) they gave you drugs you know they help you when they take care of your problems, they cure you, you know, the next time you go there you say thanks to them. (Migrant 4)

Informal Patient Payments as a Regular Practice

(…) When you go to a doctor in a hospital (…) it’s tradition to also go to a private practice of this doctor, and me and my ex-wife we just never did that. (…) nobody would ask her anything like ‘are you feeling okay’. All the other patients would be constantly visited by their doctors (…) who they hired privately in their private clinics. My ex-wife’s doctor would never come and check up on her or anything like she just gave birth, and after that it was done. (Civil Servant 3)

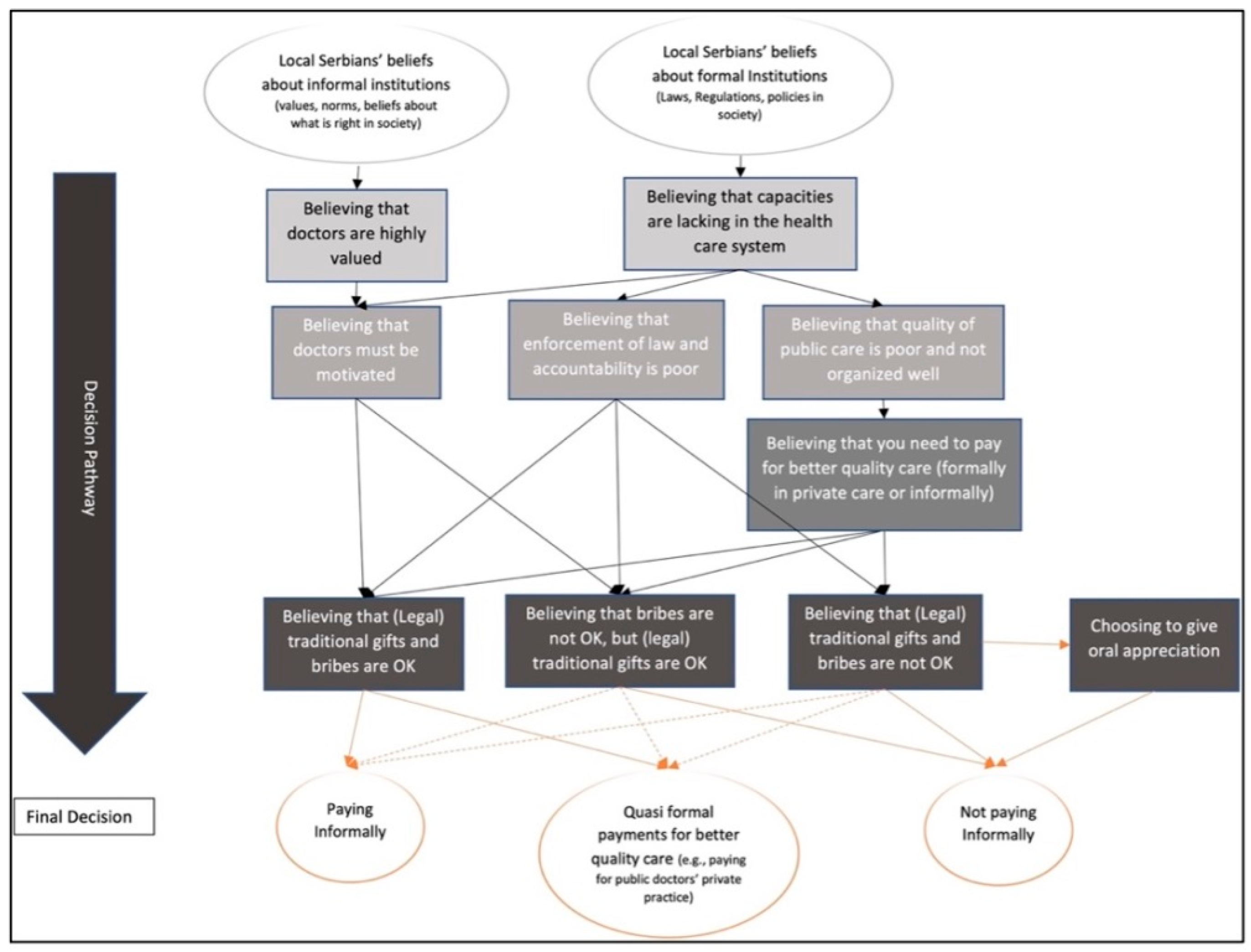

3.2. Multiperspective Perceptions on Pathways to Informal Patient Payments

3.2.1. Civil Servants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Informal Patient Payments

At the moment it looks unfixable like really there is some kind of a disease in the health care system. The problem is with the not so huge budget, and more funds is not going to solve this. Of course, you will motivate doctors and people to work better if they have better salaries and better conditions but that’s like a second thing. The first thing is that you need to do something else to improve it. (Civil Servant 6)

If you have money, that is. You would never really go to the public institutions. You would choose the private because they are just better. (Civil Servant 1)

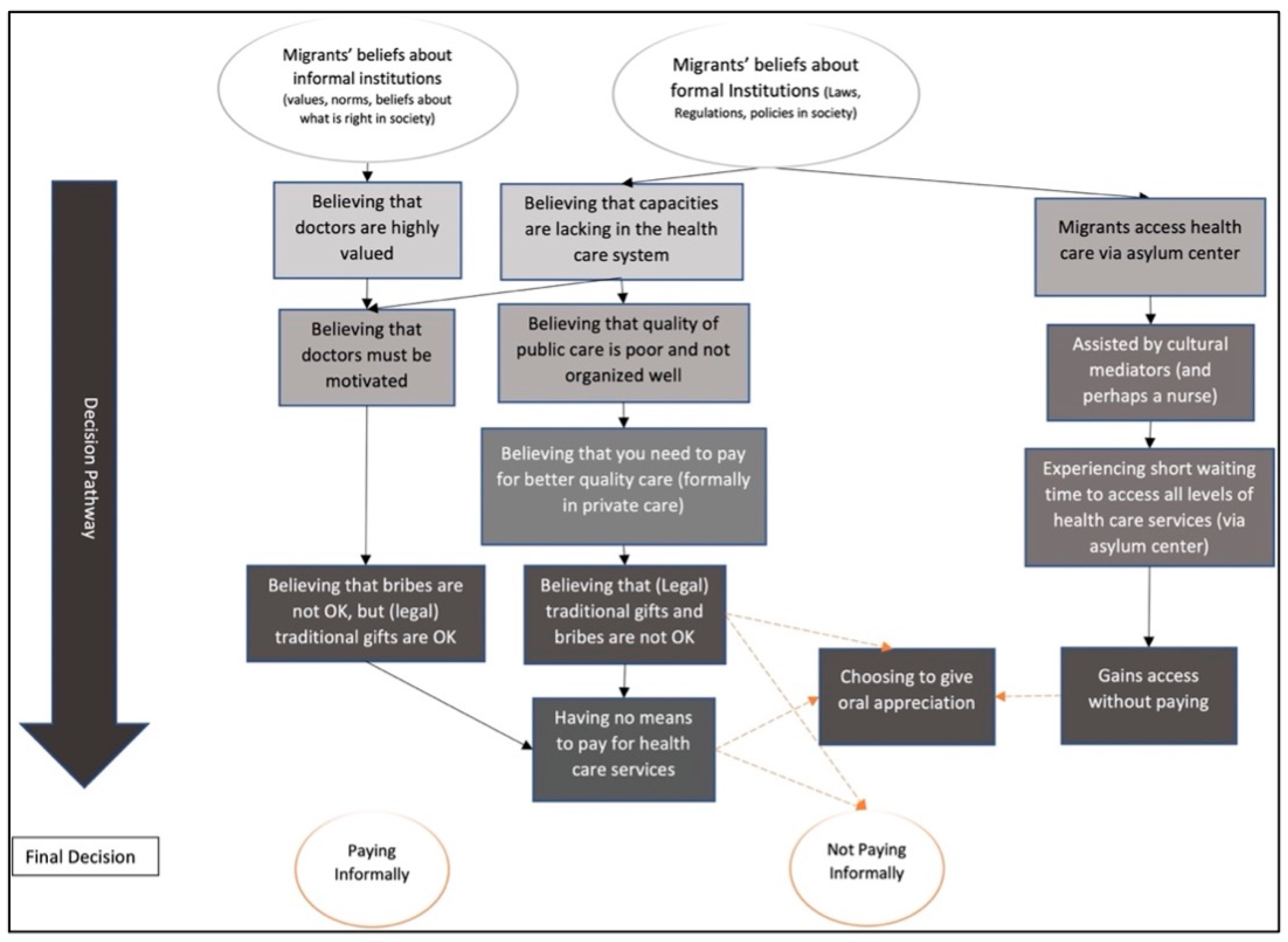

3.2.2. Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Informal Patient Payments

(…) if I have good money for sure I would go to private and (receive) good service about clinic, hospitals, staff, materials, anything. (Migrant 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Addressing the High Level of Out-of-Pocket Payments and Informal Patient Payments

4.2. Considerations about Methodology

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Health System Governance. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-systems-governance#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kickbusch, I.; Gleicher, D. Governance for Health in the 21st Century; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bigdeli, M.; Rouffy, B.; Lane, B.D.; Schmets, G.; Soucat, A.; Bellagio Group. Health systems governance: The missing links. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyone, T.; Smith, H.; van den Broek, N. Frameworks to assess health systems governance: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, H. Good governance for the public’s health. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- European Commission. European Pillar of Social Rights. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- International Organization for Migration. IOM Handbook on Protection and Assistance for Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse; International Organization of Migration: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal, R.S.; Gruer, L.; Cezard, G.; Douglas, A.; Steiner, M.F.; Millard, A.; Buchanan, D.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Sheikh, A. Mortality, ethnicity, and country of birth on a national scale, 2001–2013: A retrospective cohort (Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage Study). PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradby, H.; Humphris, R.; Newall, D.; Phillimore, J. Public Health Aspects of Migrant Health: A Review of the Evidence on Health Status for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the European Region; WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Reports; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Vito, E.; de Waure, C.; Specchia, M.L.; Ricciardi, W. Public Health Aspects of Migrant Health: A Review of the Evidence on Health Status for Undocumented Migrants in the European Region; WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Reports; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ingleby, D.E. Inequalities in Health Care for Migrants and Ethnic Minorities; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- WFP; IOM. Populations at Risk: Implications of COVID-19 for Hunger, Migration and Displacement—An Analysis of Food Security Trends in Major Hotspots; World Food Programme; International Organization for Migration: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.; Lulle, A.; Sampaio, D.; Vullnetari, J. Unpacking the ageing–migration nexus and challenging the vulnerability trope. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmusi, D.; Borrell, C.; Benach, J. Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DG Sante. The State of Health in the EU: Companion Report 2019; European Commission, OECD and the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Brussles, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.; Kiss, N.; Laszewska, A.; Mayer, S. Public Health Aspects of Migrant Health: A Review of the Evidence on Health Status for Labour Migrants in the European Region; WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Reports; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laverack, G. The Challenge of promoting the health of refugees and migrants in Europe: A review of the literature and urgent policy options. Challenges 2018, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, M.; Razum, O.; Tezcan-Güntekin, H.; Krasnik, A. Aging and health among migrants in a European perspective. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavli, A.; Maltezou, H. Health problems of newly arrived migrants and refugees in Europe. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, N. The Public Health Dimension of the European Migrant Crisis. European Parliament Briefing, Members’ Research Service PE 573.908; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Apt, W. Demographic Changes and Migration; Final Report; VDI/VDE Innovation + Technik: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Together on the Road to Universal Health Coverage. A Call to Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, V. Understanding transit asylum migration: Evidence from Serbia. Int. Migr. 2016, 54, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, D.; Bukvic, R. European Migrant Crisis (2014–2018) and Serbia. In Serbia: Current Political, Economic and Social Issues and Challenges; Janev, I., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Serbia: Assessing Health-System Capacity to Manage Sudden Large Influxes of Migrants; The Ministry of Health of Serbia, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Danish, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan for Europe-Eastern Mediterranean and Western Balkans Route. January to December 2016 (Revision May 2016); United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. Migration flows to Europe—2017 Quarterly Overview—March; International Organization for Migration: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. Operational Portal. Mediterranean Situation. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Permanand, G.; Krasnik, A.; Kluge, H.; McKee, M. Europe’s migration challenges: Mounting an effective health system response. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawson, N. Thousands of Refugee Children Sleeping Rough in Sub-Zero Serbia, Says UN The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/weather/2017/jan/24/thousands-refugee-children-sleep-rough-sub-zero-serbia-un2017 (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Mizik, R.; Karajicic, S. Serbia: Brief Health System Review. Available online: http://www.hpi.sk/en/2014/01/serbia-brief-health-system-review/ (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V.; Vasic, M.; Vukovic, D.; Jankovic, J.; Jovic-Vranes, A.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. Serbia: Health System Review; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; ISBN 1817-6119. [Google Scholar]

- Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V.; Vasic, M.; Vukovic, D.; Jankovic, J.; Jovic-Vranes, A.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. Towards equal access to health services in Serbia. Eurohealth 2020, 26, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Krstic, K.; Janicijevic, K.; Timofeyev, Y.; Arsentyev, E.V.; Rosic, G.; Bolevich, S.; Reshetnikov, V.; Jakovljevic, M.B. Dynamics of Health Care Financing and Spending in Serbia in the XXI Century. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Employment and Social Reform Programme in the Process of Accession to the European Union; Government of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2016.

- Rašević, M. Migration and Development in Serbia; International Organization for Migration: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Buch Mejsner, S.; Eklund Karlsson, L. Informal payments and health system governance in serbia: A pilot study. Sage Open 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouchos, T.V.; Vozikis, A.; Koufopoulou, P.; Fawkes, L.; Souliotis, K. Informal out-of-pocket payments for healthcare services in Greece. Health Policy 2020, 124, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomini, S.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Informal payments and intra-household allocation of resources for health care in Albania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaal, P.; Belli, P.C.; McKee, M.; Szocska, M. Informal payments for health care: Definitions, distinctions, and dilemmas. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2006, 31, 251–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaal, P.; McKee, M. Fee-for-service or donation? Hungarian perspectives on informal payment for health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Informal payments and the financing of health care in developing and transition countries. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtaleb, A.; Jafari, M.; Seyedin, H.; Behbahani, A.A. New insight into the informal patients’ payments on the evidence of literature: A systematic review study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.M.; Bahadori, M.; Motaghed, Z.; Ravangard, R. Factors affecting informal patient payments: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Health Gov. 2019, 24, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grødeland, Å.B. Public perceptions of corruption and anti-corruption reform in the Western Balkans. Slavon. East Eur. Rev. 2013, 91, 535–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, D.R.; Hutchinson, P.L.; Malaj, A.; Berruti, A.A. Out-of-pocket payments and utilization of health care services in Albania: Evidence from three districts. Health Policy 2005, 75, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupic, F.; Krupic, R.; Jasarevic, M.; Sadic, S.; Fatahi, N. Being immigrant in their own country: Experiences of Bosnians immigrants in contact with health care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mater. Socio-Med. 2015, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejsner, S.B.; Karlsson, L.E. Informal patient payments and bought and brought goods in the Western Balkans—A scoping review. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, D. Does corruption undermine trust in health care? Results from public opinion polls in Croatia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 98, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, M.; Rechel, B.; Mayhew, S.H. Access of Roma to sexual and reproductive health services: Qualitative findings from Albania, Bulgaria and Macedonia. Glob. Public Health 2012, 7, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Z.; Severoni, S.; Puthoopparambil, S.J.; Vuksanovic, H.; Stojkovic, S.G.; Egic, V.; WHO Organization. Refugee and migrant health: Improving access to health care for people in between. Public Health Panor. 2018, 4, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenijevic, J.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Shortcomings of maternity care in Serbia. Birth 2014, 41, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, W.; Bozikov, J.; Rechel, B. Health Reforms in South-East Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rašević, M. Serbia: The migration issue in key national strategies. In Towards Understanding of Contemporary Migration—Cause, Consequences, Policies, Reflections; Bobić, M., Janković, S., Eds.; Institute for Sociological Research Faculty of Philosophy University of Belgrade, Serbian Sociological Society; Institute for Sociological Research: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, A.; O’Donnell, P.; O’Keeffe, M.; MacFarlane, A. How do Variations in Definitions of “Migrant” and Their Application Influence the Access of Migrants to Health Care Services; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, S.; Giacco, D.; El-Nagib, R. Public Health Aspects of Mental Health among Migrants and Refugees: A Review of the Evidence on Mental Health Care for Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Irregular Migrants in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, B.; Schatzman, L. Dimensional Analysis. In Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation; Morse, J., Noerager Stern, P., Corbin, J., Bowers, B., Charmaz, K., Clarke, A., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 88–127. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, S.; Swail, J.; Williams, C.C. Entrepreneurship in the Informal Sector: An Institutional Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C.; Horodnic, A.V. Explaining informal payments for health services in Central and Eastern Europe: An institutional asymmetry perspective. Post Communist Econ. 2018, 30, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Horodnic, I.A. Explaining the prevalence of illegitimate wage practices in Southern Europe: An institutional analysis. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2015, 20, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Burke, N.; Somkin, C.P.; Pasick, R. Considering culture in physician—Patient communication during colorectal cancer screening. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantović, L. Not-So-Informal Relationships. Selective Unbundling of Maternal Care and the Reconfigurations of Patient–Provider Relations in Serbia. Südosteuropa 2018, 66, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambolović, V.; Đurić, M.; Đonić, D.; Kelečević, J.; Rakočević, Z. Patient–physician relationship in the aftermath of war. J. Med. Ethics 2006, 32, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G. Culture and the patient-physician relationship: Achieving cultural competency in health care. J. Pediatrics 2000, 136, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrasevic, M.; Radovanovic, S.; Radevic, S.; Maricic, M.; Macuzic, I.Z.; Kanjevac, T. The Unmet Healthcare Needs: Evidence from Serbia. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care on the Road to Universal Health Coverage: 2019 Monitoring Report: Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenijevic, J.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Out-of-pocket payments for health care in Serbia. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomini, S.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Paying informally in the Albanian health care sector: A two-tiered stochastic frontier model. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2012, 13, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vian, T.; Grybosk, K.; Sinoimeri, Z.; Hall, R. Informal payments in government health facilities in Albania: Results of a qualitative study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghadouch, A.; Norredam, M. Psychosocial Responses to Healthcare: A Study on Asylum-Seeking Families’ Experiences in Denmark. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funge, J.K.; Boye, M.C.; Johnsen, H.; Nørredam, M. “No Papers. No Doctor”: A Qualitative Study of Access to Maternity Care Services for Undocumented Immigrant Women in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. EUR/RC66/8 Strategy and Action Plan for Refugee and Migrant Health in the WHO European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D.; Kristiansen, M.; Krasnik, A.; Norredam, M. Access to healthcare and alternative health-seeking strategies among undocumented migrants in Denmark. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, V.; Arsić, M.; Nojković, A. Public debt sustainability in Serbia before and during the global financial crisis. Econ. Ann. 2016, 61, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M.M.; Netz, Y.; Buttigieg, S.C.; Adany, R.; Laaser, U.; Varjacic, M. Population aging and migration–history and UN forecasts in the EU-28 and its east and south near neighborhood–one century perspective 1950–2050. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitović, V.; Lukić, V. Could refugees have a significant impact on the future demographic change of Serbia? Int. Migr. 2010, 48, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, M.L.; Kennedy, D. Innovation in Medical Technology: Ethical Issues and Challenges; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Key Components of a Well Functioning Health System; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/EN_HSSkeycomponents.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Out-of-Pocket Payments, User Fees and Catastrophic Expenditure. Available online: https://www.who.int/health_financing/topics/financial-protection/out-of-pocket-payments/en/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database: Out-of-Pocket Expenditure. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=RS (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Aasland, A.; Grødeland, Å.B.; Pleines, H. Trust and Informal Practice among Elites in East Central Europe, South East Europe and the West Balkans. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2012, 64, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodamoradi, A.; Ghaffari, M.P.; Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara, R.; Sajadi, H.S.; Majdzadeh, R. A systematic review of empirical studies on methodology and burden of informal patient payments in health systems. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e26–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.; Wismar, M.; Figueras, J. Strengthening Health System Governance: Better Policies, Stronger Performance; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, S.; Masud, T.I.; Nishtar, S.; Peters, D.H.; Sabri, B.; Bile, K.M.; Jama, M.A. Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing countries: Gateway to good governance. Health Policy 2009, 90, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, S.; Tanggaard, L. Kvalitative metoder, tilgange og perspektiver. In Kvalitative Metoder: En Grundbog; Hans Reitzels Forlag: Copenhagen, Danish, 2020; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Newington, L.; Metcalfe, A. Factors influencing recruitment to research: Qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of research teams. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, K.; Dragano, N.; Ellert, U.; Fricke, J.; Greiser, K.H.; Keil, T.; Krist, L.; Moebus, S.; Pundt, N.; Schlaud, M. Comparing sampling strategies to recruit migrants for an epidemiological study. Results from a German feasibility study. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, P.; Kaczorowski, J.; Berry, N. Recruitment of Refugees for Health Research: A qualitative study to add refugees’ perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, L.; Knierim, B.; Barth, J.; Liewald, K.; Duetz, M.; Abel, T. From text to codings: Intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruschka, D.J.; Schwartz, D.; St. John, D.C.; Picone-Decaro, E.; Jenkins, R.A.; Carey, J.W. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods 2004, 16, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, K.A. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2012, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; House, J.S.; Gravlee, C.C.; Miranda, P.Y.; Miller, P.; Kannan, S. Inter-rater and test–retest reliability: Methods and results for the neighborhood observational checklist. Health Place 2007, 13, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buch Mejsner, S.; Kristiansen, M.; Eklund Karlsson, L. Civil Servants and Non-Western Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Health Care in Serbia—A Grounded Theory, Multi-Perspective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910247

Buch Mejsner S, Kristiansen M, Eklund Karlsson L. Civil Servants and Non-Western Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Health Care in Serbia—A Grounded Theory, Multi-Perspective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910247

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuch Mejsner, Sofie, Maria Kristiansen, and Leena Eklund Karlsson. 2021. "Civil Servants and Non-Western Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Health Care in Serbia—A Grounded Theory, Multi-Perspective Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910247

APA StyleBuch Mejsner, S., Kristiansen, M., & Eklund Karlsson, L. (2021). Civil Servants and Non-Western Migrants’ Perceptions on Pathways to Health Care in Serbia—A Grounded Theory, Multi-Perspective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910247